Abstract

The canonical transient receptor potential channels (TRPCs) constitute a series of nonselective cation channels with variable degrees of Ca2+ selectivity. TRPCs consist of seven mammalian members, TRPC1, TRPC2, TRPC3, TRPC4, TRPC5, TRPC6, and TRPC7, which are further divided into four subtypes, TRPC1, TRPC2, TRPC4/5, and TRPC3/6/7. These channels take charge of various essential cell functions such as contraction, relaxation, proliferation, and dysfunction. This review, organized into seven main sections, will provide an overview of current knowledge about the underlying pathogenesis of TRPCs in cardio/cerebrovascular diseases, including hypertension, pulmonary arterial hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, atherosclerosis, arrhythmia, and cerebrovascular ischemia reperfusion injury. Collectively, TRPCs could become a group of drug targets with important physiological functions for the therapy of human cardio/cerebro-vascular diseases.

Keywords: Ca2+ signaling, Canonical transient receptor potential receptor, Cardiovascular disease, Cerebrovascular disease, Pathogenesis

INTRODUCTION

In 1969, Cosens and Manning (1969) discovered that Drosophila with mutations in a peculiar gene was defective and displayed transient light-induced receptor potentials (TRPs) in response to continuous light exposure, causing visual impairment in photoreceptor cells. This phenomenon was explained by a deletion in ion channels, and led to the discovery of “TRP genes” that were named TRP channels. To date, the TRP channels superfamily contains 28 members in mammals and is subdivided into six subfamilies: TRPA, TRPC, TRPML, TRPM, TRPN, TRPV and TRPP, all of which permeate cations (Montell, 2005). The canonical transient receptor potential channels (TRPCs) are the first encoded TRP gene family in mammals and are the most dominating non-voltage-gated, Ca2+-permeable cation channels in various cells (Zhu et al., 1995). TRPCs fall into four groups in terms of their amino acid homology and similarities in function: TRPC1, TRPC2 (as a pseudogene in humans), TRPC4/5, and TRPC3/6/7 (Table 1) (Nilius and Voets, 2005; Minke, 2006). The seven subtypes have an invariant sequence in common in the C-terminal tail called a TRP box (Philipp et al., 2000) and include three to four ankyrin-like repetitive sequences in the N-terminus (Montell et al., 2002). Many subunits of TRPCs are able to coassemble. There exist heteromultimeric channels that consist of heterologously expressed and endogenous TRPC monomers (Nilius et al., 2007). Indeed, TRPC1, TPRC4 and TRPC5 can form heteromers. Similarly, TRPC3, TRPC6, and TRPC7 form heteromers. In terms of activation mechanisms, members of the TRPC3, TRPC6 and TRPC7 subtypes can be stimulated by diacylglycerol (DAG) (Hofmann et al., 1999), which is the phospholipase C (PLC)-derived production regulating their physiological activation. In contrast, the TRPC1/4/5 subgroups are completely insensitive to DAG, which is still a controversial mechanism (Venkatachalam et al., 2003).

Table 1.

The properties of the TRPC family members

| Category | Tissue distribution | Structure | Activation mechanism | Proposed regulation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRPC1 | Heart, Cartilage, Pituitary gland, Cerebellum, Caudate nucleus, Amygdala. | Six transmembrane spanning domains, TRP box in the C-terminus and three to four ankyrin-like repetitive sequences in the N-terminus | PKC-dependent phosphorylation | Store-operated, Store depletion | Riccio et al., 2002; Nilius and Voets, 2005; Minke, 2006; Xia et al., 2014 |

| TRPC3 | Pituitary gland, Cerebellum, Caudate nucleus, Putamen, Striatum. | Ibid ibidem | PKC-independent mechanism | DAG, Store-operated, Store depletion | Riccio et al., 2002; Welsh et al., 2002; Minke, 2006 |

| TRPC4 | Prostate, Bone. Parahippocampus. | Ibid ibidem | G-protein-coupled agonists | Store-operated, Store depletion? | Schaefer et al., 2000; Riccio et al., 2002; Plant and Schaefer, 2003 |

| TRPC5 | Cerebellum, Middle frontal gyrus, superior frontal gyrus | Ibid ibidem | G-protein-coupled agonists | Store-operated, Store depletion? | Schaefer et al., 2000; Riccio et al., 2002; Plant and Schaefer, 2003 |

| TRPC6 | Heart, Kidney, Adipose, Prostate, Cerebellum, Cingulate gyrus. | Ibid ibidem | PKC-independent mechanism | DAG, Receptor-operated | Riccio et al., 2002; Welsh et al., 2002; Winn et al., 2005; Xia et al., 2014 |

| TRPC7 | Pituitary gland, Kidney, Intestine, Prostate, Brain, Testis, Spleen, Cartilage. | Ibid ibidem | PKC-independent mechanism | DAG, Store depletion | Okada et al., 1999; Riccio et al., 2002 |

| TRPC2 | Only expressed in rodent, | Ibid ibidem | PLC-dependent mechanism | DAG, Store depletion? | Leypold et al., 2002; Stowers et al., 2002 |

“?” indicates that the proposed regulation is not completely confirmed.

Most TRPCs are inserted in the plasma membrane (PM) and can be hindered by blockers (Zhang et al., 2013). Generally speaking, G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) have important roles in the regulation of TRPCs. In some cases, lipid signals can regulate the signals from GPCRs to TRPCs (Kukkonen, 2011).

A cytosolic Ca2+ change may be induced by activation of specific GPCRs, including an initial transient increase resulting from release of calcium ions from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)/sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) and a subsequent sustained plateau phase via receptor-operated channels (ROCs) (Berridge et al., 2003). This latter manner of Ca2+ entry is named “receptor-operated Ca2+ entry” (ROCE) (Soboloff et al., 2005; Inoue et al., 2009). Another manner of Ca2+ entry has been termed “store-operated Ca2+ entry” (SOCE) via store-operated channels (SOCs) (Shi et al., 2016). SOCE occurs linked to depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores (Putney, 1986; Ng and Gurney, 2001). Ca2+ refills depleted intracellular Ca2+ storages, directly accessing the SR/ER via SOCE. Although the exact functional relationship between TRPC and SOCE/ROCE is still indistinct, it is clear that TRPCs are the main channels of SOCs and ROCs. In recent years, SOCs and ROCs have gained increased attention for their role in mediating Ca2+ influx in response to cell function and disease. Previous studies suggested that TRPC family members, except TRPC2, are detectable at the mRNA level in the whole heart, vascular system, cerebral arteries, smooth muscle cells (SMCs) and endothelial cells (ECs) (Yue et al., 2015). TRPCs may participate in most cardio/cerebro-vascular diseases (Table 2) and play important roles in reactive Ca2+-signaling in the cardio/cerebro-vascular system (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

TRPC channels may participate in most cardio/cerebro-vascular diseases

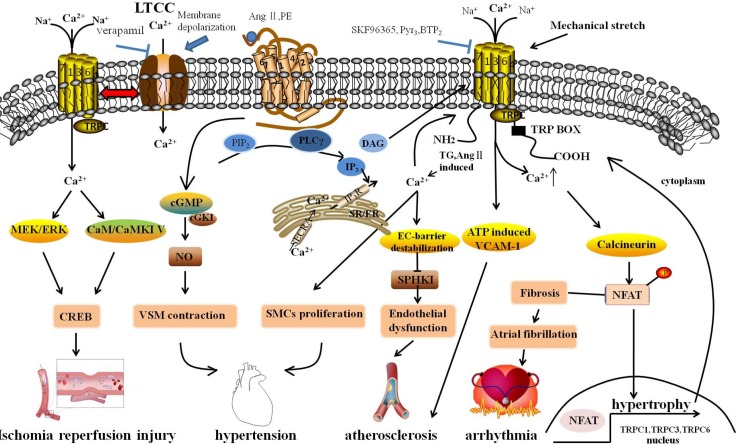

Fig. 1.

Molecular mechanism underlying cardiovascular diseases associated with the changing of intracellular Ca2+ through TRPCs. GPCRs, releasing DAG and IP3 via PIP2 with the subsequent activation of PLC, were stimulated by Ang II and PE, which were hypertrophic stimuli. DAG stimulated ROCs, including TRPC3 and TRPC6, resulting in extracellular Ca2+ influx. IP3 activated SOCE in response to depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores by Ca2+ release in the SR/ER and subsequently activated TRPCs. The sustained TRPC-mediated Ca2+ entry directly activated the calcineurin-NFAT pathway, subsequently resulting in the activation of hypertrophic gene expression, including TRPC1, TRPC3 and TRPC6. Simultaneously, after activating, NFAT might activate TRPC gene expression through a positive feedback mechanism. TRPCs interacted with the LTCC through membrane depolarization, playing a role in regulation of cardiac pacemaking, conduction, ventricular activity, and contractility. Mechanical stretch caused arrhythmia through the activation of SACs to elevate cytosolic Ca2+ levels. Fibroblast regulated by Ca2+-permeable TRPCs might be associated with AF, and fibroblast proliferation and differentiation are a central feature in AF-promoting remodeling. TRPCs maintained adherens junction plasticity and enabled EC-barrier destabilization by suppressing SPHK1 expression to induce endothelial hyperpermeability, leading to atherosclerosis. In addition, the omission of extracellular Ca2+ with channel blockers (SKF96365, Pyr3) reduced monocyte adhesion and ATP-induced VCAM-1 and also relieved the progress of atherosclerosis. The rise of cytosolic [Ca2+]i promoted SMC proliferation. TRPC channels associated with vascular remodeling caused hyperplasia of SMCs. Moreover, TRPCs participated in blood pressure regulation due to receptor-mediated and pressure-induced changes in VSMC cytosolic Ca2+. Signaling via cGKI in vascular smooth muscle, by which endothelial NO regulated vascular tone, caused VSMC contraction. Activated TRPCs can activate downstream effectors and CREB proteins that have many physiological functions; TRPCs activated in neurons are linked to numerous stimuli, including growth factors, hormones, and neuronal activity through the Ras/MEK/ERK and CaM/CaMKIV pathways. GPCRs, G protein-coupled receptor; Ang II, Angiotensin II; PE, phenylephrine; ROCs, receptor-operated channels; SOCE, store-operated Ca2+ entry; LTCC, L-type voltage-gated calcium channel; SACs, stretch-activated ion channels; AF, atrial fibrillation; SPHK1, sphingosine kinase 1; VCAM-1, Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; SMCs, smooth muscle cells; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cells; cGKI, cGMP-dependent protein kinase I; CREB, cAMP/Ca2+-response element-binding.

Role of TRPCs in hypertension

Hypertension is a chronic cardiovascular disease characterized by persistently elevated blood pressure and is a major risk factor for coronary artery disease, stroke, heart failure, and peripheral vascular disease. In recent years, numerous studies have focused on the relationship between primary hypertension and TRPCs (Fuchs et al., 2010). In pathological states, some signaling factors are involved in the transition of SMCs into the proliferative phenotype, leading to an excessive growth of SMCs (Beamish et al., 2010). Abnormal over-growth of SMCs is implicated in various vascular diseases, including hypertension (Beamish et al., 2010). Previous studies have convincingly suggested that several TRPC members are involved in hyperplasia of SMCs. TRPC1/3/6 all have been involved in enhanced proliferation and phenotype switching of SMCs (Dietrich et al., 2005; Takahashi et al., 2007; Koenig et al., 2013). Kumar et al. (2006) suggested that TRPC1 was up-regulated in rodent vascular injury models and in human neointimal hyperplasia after vascular damage. In coronary artery SMCs, upregulation of TRPC1 results in angiotensin-II (Ang II)-mediated human coronary artery SMC proliferation (Takahashi et al., 2007). Moreover, other studies found that the visible whole-cell currents were triggered by passive depletion of Ca2+ storages in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) in wild type mice, but not in Trpc1−/− mice (Shi et al., 2012), suggesting TRPC1 contributed to the alteration of whole-cell currents in VSMCs (Shi et al., 2012).

In addition, TRPC3 also plays a pivotal role in Ca2+ signaling and a pathophysiological role in hypertension. The previous studies suggested TRPC3 levels were elevated in patients with hypertension as well as in the pressure-overload rat and the spontaneous hypertensive rat (SHR) models (Liu et al., 2009; Onohara et al., 2006; Thilo et al., 2009). In monocytes, DAG-, thapsigargin-and Ang II-induced Ca2+ influxes were elevated in response to pathological state in SHR. However, further studies proved that downregulating TRPC3 by siRNA or applying with Pyrazole-3 (Pyr3), a highly selective inhibitor of TRPC3, reduced DAG-, thapsigargin- and Ang II-induced Ca2+ influx in monocytes from SHR (Liu et al., 2007a; Chen et al., 2010), prevented stent-induced arterial remodeling, and inhibited SMC proliferation (Yu et al., 2004; Schleifer et al., 2012). Similarly, compared with normotensive patients, increased expression of TRPC3 and a subsequent increase in SOCE has been noticed in monocytes from hypertension patients (Liu et al., 2006, 2007b). These data show a positive association between blood pressure and TRPC3, indicating an underlying role for TRPC3 in hypertension.

TRPC6 is a ubiquitous TRPC isoform expressed in the whole vasculature, which plays a pivotal role in blood pressure regulation because of its physiological importance in both receptor-mediated and pressure-induced increases of cytosolic Ca2+ in VSMCs (Toth et al., 2013). Studies suggested that cGMP-dependent protein kinase I (cGKI), which was implicated in the regulation of smooth muscle relaxation, inhibited the activity of TRPCs in SMCs (Kwan et al., 2004; Takahashi et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2009; Dietrich et al., 2010) and regulated vascular tone via endothelial nitric oxide (NO) (Loga et al., 2013). However, the knockout of TRPC6 might injure endothelial cGKI signaling and vasodilator tone in the aorta (Loga et al., 2013). Although deletion of TRPC6 decreases SMC contraction and depolarization induced by pressure in arteries, the basal mean arterial pressure in Trpc6−/− mice is about more than 7 mm Hg higher than that in wild type mice (Welsh et al., 2002; Dietrich et al., 2005), indicating that TRPC6 participated in smooth muscle contraction. Similarly, in deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt-hypertensive rats, overexpression of TRPC6 strengthened agonist mediated VSMC contractility companied with increased mean blood pressure (Bae et al., 2007). Additionally, mineralocorticoid receptor-induced TRPC6 mRNA level was elevated in the aldosterone-treated rat A7r5 VSMCs, suggesting that heightened TRPC6 expression importantly participates in increased VSM reactivity (Bae et al., 2007).

Role of TRPCs in pulmonary arterial hypertension

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is characterized by a thickening of the pulmonary arterial walls, which can cause right heart failure (Yu et al., 2004). Increased pulmonary vascular resistance is a primary factor in the progression of PAH. Ca2+ entry from the extracellular space, acting as a crucial mediator, is implicated in vasoconstriction (through its pivotal effect on pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs) contraction) and vascular remodeling (through its stimulatory effect on PASMC proliferation) (Kuhr et al., 2012; Weber et al., 2015). The most frequently expressed isoforms of TRPC in VSMCs are TRPC1, TRPC4, and TRPC6; TRPC3, TRPC5, and TRPC7 are less frequently detected (Inoue et al., 2006; Maier et al., 2015). Studies showed that Ca2+ entry improved the level of cytosolic Ca2+ through SOCs and ROCs (which is formed by TPRCs), and sufficient Ca2+ in the SR induced VSMC proliferation (Birnbaumer et al., 1996; Golovina et al., 2001; Bergdahl et al., 2003; Satoh et al., 2007; Seo et al., 2014).

TRPC1, TRPC4 and TRPC6 are involved in hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction, which is related to increased SOCE. Additionally, SOCE contributes to basal intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and the proliferation and migration of PASMCs in rat (Lu et al., 2008). Malczyk et al. (2013) demonstrated that TRPC1 played an important role in hypoxia-induced PAH, as hypoxia-induced PAH is alleviated in Trpc1−/− mice. Xia et al. (2014) found that TRPC1/6 are crucial for the regulation of neo-muscularization, vasoreactivity, and vasomotor tone of pulmonary vasculatures; the combined actions of the two channels have a distinctly larger influence using Trpc1−/−, Trpc6−/− and Trpc1−/−/Trpc6−/− mice. Significantly, another study confirmed the upregulation of TRPC1/6 expression in murine chronic hypoxia PAH models (Wang et al., 2006). Silence of TRPC1 and TRPC6 specifically attenuated thapsigargin-and 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG)-induced cation entries, respectively, indicating that TRPC1-mediated SOCE and TRPC6-mediated ROCE are upregulated by chronic hypoxia (Lin et al., 2004). TRPC4 is also involved in PAH. In monocrotaline-induced PAH rats, TRPC1 and TRPC4 protein levels were both increased significantly, resulting in enhanced vasoconstriction to endothelin-1 (ET-1) (Liu et al., 2012). In addition, siRNA specifically targeting TRPC4 reduced increases in TRPC4 expression and capacitative calcium entry (CCE) amplitude and inhibited ATP-induced PASMC proliferation (Zhang et al., 2004).

The expression and function of TRPCs are variously regulated by molecules in PAH. Wang et al. (2015) implied that both bone morphogenetic protein-4 (BMP4) and hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) upregulated TRPC1 and TRPC6, leading to elevated basal [Ca2+]i in PASMCs, driving the development of chronic hypoxia-induced PAH (Wang et al., 2015). Another study found that TRPC expression was found absent in mice partially deficient for HIF-1α (Wang et al., 2006). In human PASMCs, siRNA of the HIF-1α reduced hypoxia-induced BMP4 expression and knockout of either HIF-1α or BMP4 abrogated hypoxia-induced basal cytosolic Ca2+ increase and TRPC expression (Zhang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015). Also, TRPCs have been recognized as reactive oxygen species (ROS)-activated channels and it is suggested that they are critical for hypoxia associated with vascular regulatory procedures in lung tissue.

TRPCs could be regulated by pharmacological intervention during PAH. The treatment of experimental PAH with sildenafil and sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate suppresses TRPC1/6 expression (Lu et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013a). SAR7334, an inhibitor of TRPC6, suppresses native TRPC6 activity in vivo (Maier et al., 2015) and opens new opportunities for the investigation of TRPC function. In the lung and PASMC from idiopathic PAH patients, the mRNA and protein expression levels of TRPC6 were much higher than that from normotensive or secondary PAH patients. Also, inhibition of TRPC6 expression markedly attenuated idiopathic PAH-PASMC proliferation (Yu et al., 2004). As a consequence, the participation of TRPC1/4/6 are crucial for PAH.

These results suggest that overexpression of TRPC may partially contribute to the increased PASMC proliferation, hinting at a promising therapeutic strategy for PAH patients.

Role of TRPCs in cardiac hypertrophy

Cardiac hypertrophy serves as a common pathway in cardiovascular diseases. It is the most important pathological foundation resulting in cardiogenic death. Although one study showed that the knockout of some TRPC genes did not result in abnormality in normal mice hearts (Yue et al., 2015). TRPCs have been demonstrated to play an important role in the pathological progress of cardiac hypertrophy through the mediation of ion channel activities and downstream signaling. Dysregulation of TRPCs may lead to maladaptive cardiac hypertrophy.

Numerous studies have shown that TRPC expression and activity are up-regulated in pathological cardiac hypertrophy (Bush et al., 2006; Kuwahara et al., 2006; Ohba et al., 2007; Seth et al., 2009). Cardiac hypertrophy induced by transverse aortic constriction (TAC) was improved in Trpc1−/− mice. Meanwhile, downregulation of TRPC1 reduced SOCE and prevented ET-1-, Ang II-, and phenylephrine (PE)-induced cardiac hypertrophy, indicating that deletion of TRPC1 avoided harmful influences in response to increased cardiac stresses in Trpc1−/− mice (Ohba et al., 2007). Also verified that TRPC1-mediated Ca2+ entry stimulated hypertrophic signaling in cardiomyocytes (Seth et al., 2009). Similarly, cardiac pathological hypertrophy could be caused by stimulation of pressure overload or overexpression of the TRPC3 gene in cardiomyocytes from TRPC3 transgenic mice, and could be selectively inhibited by Pyr3 (Nakayama et al., 2006; Kiyonaka et al., 2009). Also, TRPC6 has been proposed as a critical target of anti-hypertrophic effects elicited via the cardiac ANP/BNP-GC-A pathway (Kinoshita et al., 2010). However, a recent study showed Trpc6−/− mice resulted in an obvious augment in the cardiac mass/tibia length (CM/TL) ratio after Ang II, while the Trpc3−/− mice showed no alteration after Ang II injection. However, the protective effect against hypertrophy of pressure overload was detected in Trpc3−/−/Trpc6−/− mice rather than in Trpc3−/− or Trpc6−/− mice alone (Seo et al., 2014). Similarly, the newly developed selective TRPC3/6 dual blocker showed an obvious inhibition to myocyte hypertrophy signaling activated by Ang II, ET-1 and PE in a dose-dependent manner in HEK293T cells as well as in neonatal and adult cardiomyocytes (Seo et al., 2014).

Although the TRPCs role in myocardial hypertrophy is controversial, it is generally believed that calcineurin-nuclear factor of activated T-cells (Cn/NFAT) is a critical factor of microdomain signaling in the heart to control pathological hypertrophy. Studies found that transgenic mice that express dominantnegative myocyte-specific TRPC3, TRPC6 or TRPC4 attenuated the reactivity following either neuroendocrine-like or pressure overload-induced pathologic cardiac hypertrophy through Cn/NFAT stimulation in vivo, demonstrating that blockades of TRPCs are necessary adjusters of hypertrophy (Dietrich et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2010; Eder and Molkentin, 2011).

Undoubtedly, TRPCs play an important role in cardiac hypertrophy and can be regarded as new therapeutic target in the development of new drugs.

Role of TRPCs in atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is commonly considered a chronic disease with dominant accumulation of lipids and inflammatory cells of the arterial wall throughout all stages of the disease (Tabas et al., 2010). Several types of cells such as VSMCs, ECs, monocytes/macrophages, and platelets are involved in the pathological mechanisms of atherosclerosis.

It has been reported that the participation of proliferative phenotype of VSMCs is a consequential part in atherosclerosis. Cytoplasmic Ca2+ dysregulation via TRPC1 can mediate VSMC proliferation (Edwards et al., 2010). Studies have established that TRPC1 is implicated in coronary artery disease (CAD), during which the expression of TRPC1 mRNA and protein are elevated (Cheng et al., 2008; Edwards et al., 2010). Kumar et al. (2006) showed the upregulated TRPC1 in hyperplastic VSMCs was related to cell cycle activity and enhanced Ca2+ entry using a model of vascular injury in pigs and rats. In addition, the inhibition of TRPC1 effectively attenuates neointimal growth in veins (Kumar et al., 2006). These results indicate that upregulation of TRPC1 in VSMCs is a general feature of atherosclerosis.

The vascular endothelium is a polyfunctional organ, and ECs can generate extensive factors to mediate cellular adhesion, smooth muscle cell proliferation, thromboresistance, and vessel wall inflammation. Vascular endothelial dysfunction is the earliest detectable manifestation of atherosclerosis, which is associated with the malfunction of multiple TRPCs (Poteser et al., 2006). Tauseef et al. (2016) showed that TRPC1 maintained adherens junction plasticity and enabled EC-barrier destabilization by suppressing sphingosine kinase 1 (SPHK1) expression to induce endothelial hyperpermeability. Also, Poteser et al. (2006) demonstrated that porcine aorta endothelial cells, which co-expressed a redox-sensitive TRPC3 and TRPC4 complex, could give rise to cation channel activity. Furthermore, mice transfected with TRPC3 showed increased size and cellularity of advanced atherosclerotic lesions (Smedlund et al., 2015). In addition, studies further supported the relevance of EC migration to the healing of arterial injuries, suggesting TRPC5 and TRPC6 were activated by hypercholesterolemia, which impairs endothelial healing in vitro and in vivo (Rosenbaum et al., 2015; Chaudhuri et al., 2016).

Monocyte activation, adhesion to the endothelium, and transmigration into the sub-endothelial space are critical for early pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. The roles of TRPCs have been identified in the macrophage efferocytosis and survival, two crucial events in atherosclerosis lesion development (Tano et al., 2012). It has been shown that high D-glucose or peroxynitrite-induced oxidative stress significantly increased the expression of TRPCsin human monocytes (Wuensch et al., 2010). Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) is important in monocyte recruitment to the endothelium as a critical factor in the development of atherosclerotic lesions. Smedlund et al. suggested that inhibition of TRPC3 expression could significantly attenuate ATP-induced VCAM-1 and monocyte adhesion (Smedlund and Vazquez, 2008; Smedlund et al., 2010), indicating TRPC3 is involved in atherosclerosis lesion development. The platelet also plays important roles in cardiovascular diseases, especially in atherosclerosis, by participating in the formation of thrombosis and the induction of inflammation (Wang et al., 2016). Liu et al. (2008) investigated platelets in type II diabetes mellitus (DM) patients and found a time-dependent and concentration-dependent amplification of TRPC6 expression on the platelet membrane after challenge with high glucose. These results indicate that the incremental expression and activation of TRPC6 in platelets of DM patients may result in the risk of increasing atherosclerosis.

In summary, the pathophysiological relevance of TRPCs in several critical progresses has been linked to atherosclerosis.

Role of TRPCs in arrhythmia

Arrhythmia is a group of conditions in which the electrical activity of the heart is irregular, either too fast (above 100 beats per minute, called tachycardia) or too slow (below 60 beats per minute, called bradycardia). Several experiments have shed light on TRPC-regulated Ca2+ entry in arrhythmia. Sabourin et al. (2011) found that the existence of TRPC1,3,4,5,6 and 7 in the atria and ventricle, via association with the L-type voltagegated calcium channel (LTCC), plays a role in the modulation of cardiac pacemaking, conduction, ventricular activity, and contractility during cardiogenesis. Mechanical stretch is one of the causes of cardiac arrhythmia. It has been demonstrated that mechanical transformation of ventricular myocytes can modulate TRPC6. The process can be inhibited by GsMTx-4, which is a peptide isolated from tarantula venom and a specific inhibitor of stretch-activated channels (SAC) (Dyachenko et al., 2009; Anderson et al., 2013; Gopal et al., 2015).

One of the most common arrhythmias is atrial fibrillation (AF) (Nattel, 2011; Wakili et al., 2011). By researching fibroblast regulation by Ca2+-permeable TRPC3, Harada et al. (2012) found that AF increased expression of TRPC3 by activating NFAT-mediated downregulation of microRNA-26. Further, they found that AF induced TRPC3-dependent increase of fibroblast proliferation and differentiation, likely by mediating the Ca2+ entry that stimulates extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling. TRPC3 blockade prevented AF substrate development in a dog model of electrically maintained AF in vivo (Harada et al., 2012). In conclusion, by promoting fibroblast pathophysiology, TRPC3 is likely to play an important role in AF.

Role of TRPCs in ischemia reperfusion injury

Tissue injury led by ischemia reperfusion is the main cause of cell apoptosis and necrosis leading to myocardial infarction, stroke, and other deadly diseases. After focal cerebral ischemia, brain injury results from a suite of pathological progresses, including inflammation, excitotoxicity, and apoptosis. Researchers have indicated that an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ is a critical step in initiating myocardial cell apoptosis and necrosis responding to ischemia reperfusion (Carafoli, 2002; Brookes et al., 2004). Several Ca2+ entry pathways, including the CCE and the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger channel, have been implicated in mediating myocardial cell Ca2+ overload (Carafoli, 2002; Brookes et al., 2004; Piper et al., 2004). An increasing number of studies show that members of the TRPC proteins are involved in regulating CCE. Given this growing evidence linking TRPC proteins to CCE in myocardial cells subjected to ischemia reperfusion injury, Liu et al. (2016) tested the assumption that increased expression of TRPC3 in myocardial cells results in increased sensitivity to the injury after ischemia reperfusion, and found that the treatment of CCE inhibitor SKF96365 markedly improved cardiomyocytes viability in response to overexpressed TRPC3. In contrast, the LTCC inhibitor verapamil had no effect (Shan et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2016). These data strongly indicate that CCE mediated through TRPCs may lead to Ca2+-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis caused by ischemia reperfusion injury.

Intracellular Ca2+ overload is also the major reason of neuronal death after cerebral ischemia. TRPC6 protein is hydrolyzed by the activation of calpain induced by intracellular Ca2+ overload in the neurons after ischemia, which precedes ischemic neuronal cell death. The inhibition of proteolytic degeneration of TRPC6 protein by blocking calpain prevented ischemic neuronal death in an animal model of stroke (Du et al., 2010). Studies found that the upregulated TRPC6 could activate downstream effectors cAMP/Ca2+-response elementbinding (CREB) proteins, which are activated in neurons linked to a number of stimuli including growth factors, hormones, and neuronal activity through the Ras/MEK/ERK and CaM/CaMKIV pathways (Shaywitz and Greenberg, 1999; Tai et al., 2008; Du et al., 2010). It was also demonstrated that enhanced CREB activation activated neurogenesis, avoided myocardial infarct expansion, and reduced the penumbra region of cerebral ischemia and infarct volumes (Zhu et al., 2004). Thus, TRPC6 neuroprotection relied on CREB activation. Similarly, Lin et al. (2013) demonstrated that resveratrol prevented cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury through the TRPC6-MEK-CREB and TRPC6-CaMKIV-CREB pathway.

The aforementioned results provide further evidence that TRPC3 and TRPC6 play roles in the mediation of cardiomyocyte function and suggest that TRPC3 and TRPC6 may contribute to increased tolerance to ischemia reperfusion injury.

DISCUSSION

Mechanisms including elevated activation or expression of TRPCs that partake in mediating Ca2+ influx activated by GPCRs offer the chance to interfere with Ca2+-dependent signaling processes, thus playing a significant role in cardio/cerebro-vascular diseases. The primary regulatory paradigm for most of these activities takes charge of total cytosolic Ca2+ or the propagation of intracellular Ca2+ signaling events that regulate cellular activity. Strong evidence indicates that TRPCs conduce to mechanical and agonist-induced SMC or fibroblast proliferation, cardiomyocytes apoptosis, and endothelium dysfunction. TRPCs were also present in Ang II-induced endothelium-dependent vasodilation and elevated contractility, regulation of vascular angiogenesis to participate in hypertension, pulmonary arterial hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, atherosclerosis, arrhythmia, and ischemia reperfusion injury. These new findings permit a more comprehensive assessment of the molecular and cellular importance of TRPCs in physiology and pathophysiology.

Many questions remain to be elucidated. Therefore, researchers should keep a watchful eye on how the novel effects of TRPCs can be committed to human cardio/cerebro-vascular diseases and clarify the clinical relevance of TRPC activities. An improved understanding of the underlying mechanisms of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases may assist in the design of new therapies and the identification of more selective pharmacological agonists and antagonists (Table 3) for TRPCs or interdependent channels as well as promote exciting chances to develop new therapies that prevent or treat cardio/cerebro-vascular diseases.

Table 3.

The essential information about inhibitors of TRPC channels or interdependent channels.

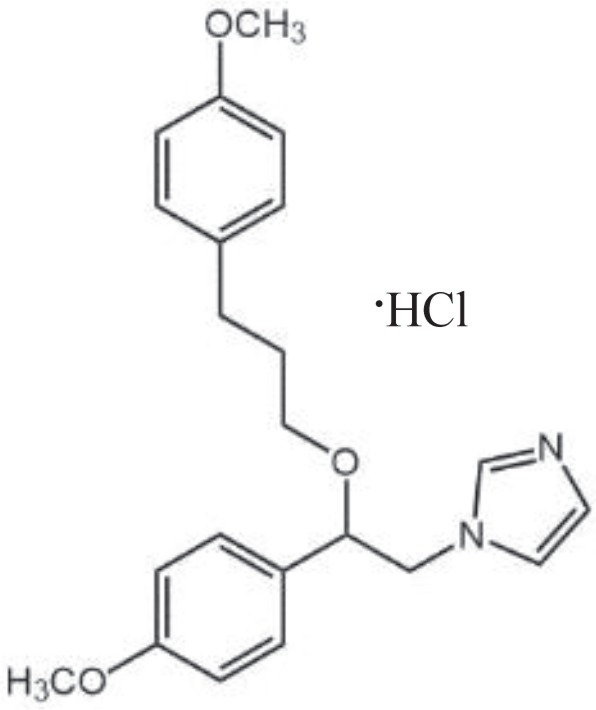

| Inhibitor | Chemical structure | Targeting channels | Predicted effects | Action mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SKF96365 |

|

TRPC1, TRPC2, TRPC3, TRPC4, TRPC5, TRPC6, TRPC7 | Selectively decrease receptor-mediated calcium entry (RMCE) in human platelets, neutrophils and endothelial cells | Inhibit receptor-mediated Ca2+ entry and voltage-gated Ca2+ entry | Merritt et al., 1990; Farooqi et al., 2013 |

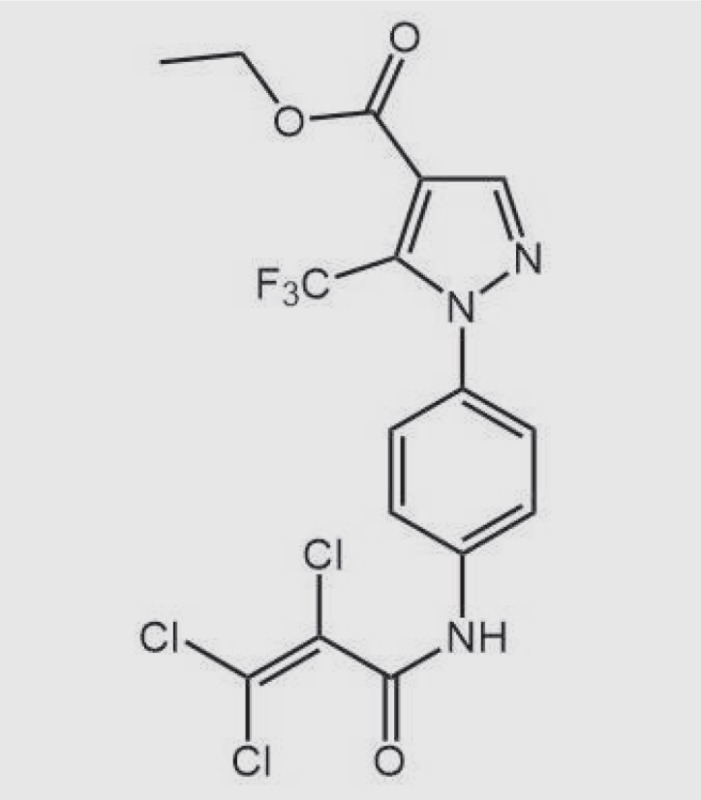

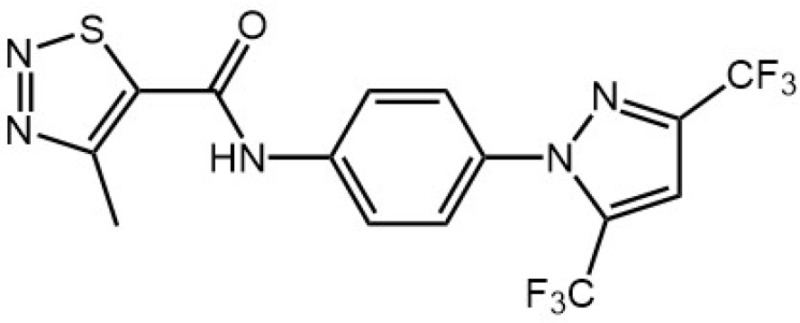

| Pyrazole-3 (Pyr3) |

|

TRPC3 | Prevent stent-induced arterial remodeling and inhibit SMC proliferation | Inhibit TRPC3 by binding to the extracellular side of the receptor | Rowell et al., 2010; Christian and Maik, 2011; Koenig et al., 2013 |

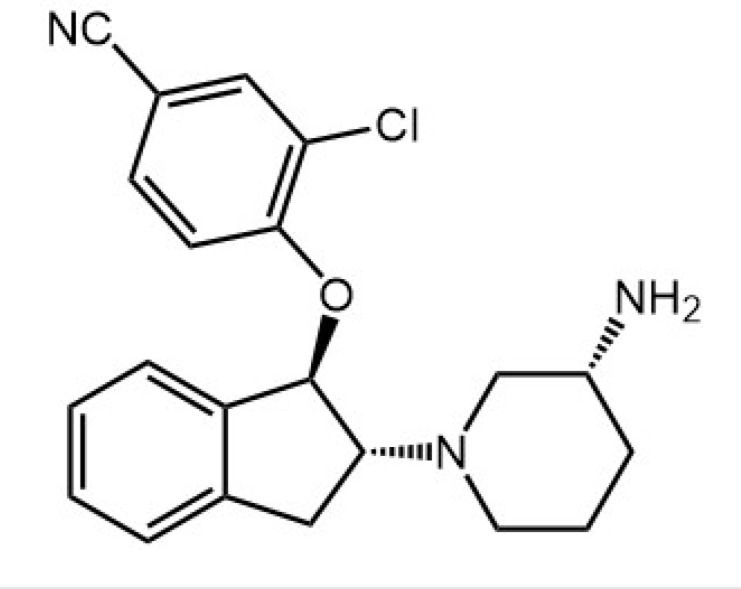

| SAR7334 |

|

TRPC3, TRPC6, TRPC7 | Effect on acute hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and systemic blood pressure | Inhibit TRPC3, TRPC6, TRPC7-mediated Ca2+ influx into cells | Maier et al., 2015 |

| GsMTx-4 | Gly-Cys-Leu-Glu-Phe-Trp-Trp-Lys-Cys-Asn-Pro-Asn-Asp-Asp-Lys-Cys-Cys-Arg-Pro-Lys-Leu-Lys-Cys-Ser-Lys-Leu-Phe-Lys-Leu-Cys-Asn-Phe-Ser-Phe-NH2 | Stretch-activated ion channels and NaV1.7 Na + channels and TRPC1, TRPC6 | Potential therapeutic targets for cardiac arrhythmias | Inhibit Na+ voltage-gated channels and cation-selective mechanosensitive channels | Franz and Bode, 2003; Bowman et al.,2007; Rowell et al., 2010 |

| BTP2 |

|

TRPCs and Store-operated Ca2+ influx and Ca2+ release-activat ed Ca2+ channels | Suppresses cytokine production (IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IFN-γ, etc.) and proliferation in T cells in vitro | Inhibit anti-CD3 antibody-induced sustained Ca2+ influx | Ohga et al., 2008; Rowell et al., 2010 |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81370241 and 81170107 to X. Q. Li) and the Social Development and Scientific and Technological Research Projects of Shaanxi province (No. 2015SF193 to X. Q. Li).

REFERENCES

- Anderson M, Kim EY, Hagmann H, Benzing T, Dryer SE. Opposing effects of podocin on the gating of podocyte TRPC6 channels evoked by membrane stretch or diacylglycerol. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2013;305:C276–C289. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00095.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae YM, Kim A, Lee YJ, Lim W, Noh YH, Kim EJ, Kim J, Kim TK, Park SW, Kim B, Cho SI, Kim DK, Ho WK. Enhancement of receptor-operated cation current and TRPC6 expression in arterial smooth muscle cells of deoxycortico-sterone acetate-salt hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2007;25:809–817. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3280148312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beamish JA, He P, Kottke-Marchant K, Marchant RE. Molecular regulation of contractile smooth muscle cell phenotype: implications for vascular tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2010;16:467–491. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2009.0630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergdahl A, Gomez MF, Dreja K, Xu SZ, Adner M, Beech DJ, Broman J, Hellstrand P, Sward K. Cholesterol depletion impairs vascular reactivity to endothelin-1 by reducing store-operated Ca2+ entry dependent on TRPC1. Circ Res. 2003;93:839–847. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000100367.45446.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Bootman MD, Roderick HL. Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:517–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaumer L, Zhu X, Jiang M, Boulay G, Peyton M, Vannier B, Brown D, Platano D, Sadeghi H, Stefani E, Birnbaumer M. On the molecular basis and regulation of cellular capacitative calcium entry: roles for Trp proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15195–15202. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman CL, Gottlieb PA, Suchyna TM, Murphy YK, Sachs F. Mechanosensitive ion channels and the peptide inhibitor GsMTx-4: history, properties, mechanisms and pharmacology. Toxicon. 2007;49:249–270. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes PS, Yoon Y, Robotham JL, Anders MW, Sheu SS. Calcium, ATP, and ROS: a mitochondrial love-hate triangle. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C817–C833. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00139.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush EW, Hood DB, Papst PJ, Chapo JA, Minobe W, Bristow MR, Olson EN, McKinsey TA. Canonical transient receptor potential channels promote cardiomyocyte hypertrophy through activation of calcineurin signaling. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:33487–33496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carafoli E. Calcium signaling: a tale for all seasons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1115–1122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032427999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri P, Rosenbaum MA, Sinharoy P, Damron DS, Birnbaumer L, Graham LM. Membrane translocation of TRPC6 channels and endothelial migration are regulated by calmodulin and PI3 kinase activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:2110–2115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600371113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Crossland RF, Noorani MM, Marrelli SP. Inhibition of TRPC1/TRPC3 by PKG contributes to NO-mediated vasorelaxation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H417–H424. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01130.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yang D, Ma S, He H, Luo Z, Feng X, Cao T, Ma L, Yan Z, Liu D, Tepel M, Zhu Z. Increased rhythmicity in hypertensive arterial smooth muscle is linked to transient receptor potential canonical channels. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2483–2494. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00890.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng KT, Liu X, Ong HL, Ambudkar IS. Functional requirement for Orai1 in store-operated TRPC1-STIM1 channels. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12935–12940. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800008200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian H, Maik G. Pharmacological Modulation of Diacylglycerol-Sensitive TRPC3/6/7 Channels. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011;12:35–41. doi: 10.2174/138920111793937943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosens DJ, Manning A. Abnormal electroretinogram from a Drosophila mutant. Nature. 1969;224:285–287. doi: 10.1038/224285a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich A, Chubanov V, Kalwa H, Rost BR, Gudermann T. Cation channels of the transient receptor potential super-family: their role in physiological and pathophysiological processes of smooth muscle cells. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;112:744–760. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich A, Kalwa H, Gudermann T. TRPC channels in vascular cell function. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:262–270. doi: 10.1160/TH09-08-0517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich A, Mederos YSM, Gollasch M, Gross V, Storch U, Dubrovska G, Obst M, Yildirim E, Salanova B, Kalwa H, Essin K, Pinkenburg O, Luft FC, Gudermann T, Birnbaumer L. Increased vascular smooth muscle contractility in Trpc6−/− mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6980–6989. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.6980-6989.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, Huang J, Yao H, Zhou K, Duan B, Wang Y. Inhibition of TRPC6 degradation suppresses ischemic brain damage in rats. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3480–3492. doi: 10.1172/JCI43165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyachenko V, Husse B, Rueckschloss U, Isenberg G. Mechanical deformation of ventricular myocytes modulates both TRPC6 and Kir2.3 channels. Cell Calcium. 2009;45:38–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eder P, Molkentin JD. TRPC channels as effectors of cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2011;108:265–272. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.225888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JM, Neeb ZP, Alloosh MA, Long X, Bratz IN, Peller CR, Byrd JP, Kumar S, Obukhov AG, Sturek M. Exercise training decreases store-operated Ca2+ entry associated with metabolic syndrome and coronary atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:631–640. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqi AA, Riaz AM, Bhatti S. TRPC signaling mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities: trapdoors are monitored by gatekeepers. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2013;26:847–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz MR, Bode F. Mechano-electrical feedback underlying arrhythmias: the atrial fibrillation case. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2003;82:163–174. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6107(03)00013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs B, Dietrich A, Gudermann T, Kalwa H, Grimminger F, Weissmann N. The role of classical transient receptor potential channels in the regulation of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;661:187–200. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-500-2_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovina VA, Platoshyn O, Bailey CL, Wang J, Limsuwan A, Sweeney M, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Upregulated TRP and enhanced capacitative Ca2+ entry in human pulmonary artery myocytes during proliferation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H746–H755. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.2.H746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopal S, Sogaard P, Multhaupt HA, Pataki C, Okina E, Xian X, Pedersen ME, Stevens T, Griesbeck O, Park PW, Pocock R, Couchman JR. Transmembrane proteoglycans control stretch-activated channels to set cytosolic calcium levels. J Cell Biol. 2015;210:1199–1211. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201501060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada M, Luo X, Qi XY, Tadevosyan A, Maguy A, Ordog B, Ledoux J, Kato T, Naud P, Voigt N, Shi Y, Kamiya K, Murohara T, Kodama I, Tardif JC, Schotten U, Van Wagoner DR, Dobrev D, Nattel S. Transient receptor potential canonical-3 channel-dependent fibroblast regulation in atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2012;126:2051–2064. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.121830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann T, Obukhov AG, Schaefer M, Harteneck C, Gudermann T, Schultz G. Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature. 1999;397:259–263. doi: 10.1038/16711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue R, Jensen LJ, Jian Z, Shi J, Hai L, Lurie AI, Henriksen FH, Salomonsson M, Morita H, Kawarabayashi Y, Mori M, Mori Y, Ito Y. Synergistic activation of vascular TRPC6 channel by receptor and mechanical stimulation via phospholipase C/diacylglycerol and phospholipase A2/omega-hydroxylase/20-HETE pathways. Circ Res. 2009;104:1399–1409. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.193227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue R, Jensen LJ, Shi J, Morita H, Nishida M, Honda A, Ito Y. Transient receptor potential channels in cardiovascular function and disease. Circ Res. 2006;99:119–131. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000233356.10630.8a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki YK, Nishida K, Kato T, Nattel S. Atrial fibrillation pathophysiology: implications for management. Circulation. 2011;124:2264–2274. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.019893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita H, Kuwahara K, Nishida M, Jian Z, Rong X, Kiyonaka S, Kuwabara Y, Kurose H, Inoue R, Mori Y, Li Y, Nakagawa Y, Usami S, Fujiwara M, Yamada Y, Minami T, Ueshima K, Nakao K. Inhibition of TRPC6 channel activity contributes to the antihypertrophic effects of natriuretic peptides-guanylyl cyclase-A signaling in the heart. Circ Res. 2010;106:1849–1860. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyonaka S, Kato K, Nishida M, Mio K, Numaga T, Sawaguchi Y, Yoshida T, Wakamori M, Mori E, Numata T, Ishii M, Takemoto H, Ojida A, Watanabe K, Uemura A, Kurose H, Morii T, Kobayashi T, Sato Y, Sato C, Hamachi I, Mori Y. Selective and direct inhibition of TRPC3 channels underlies biological activities of a pyrazole compound. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5400–5405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808793106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig S, Schernthaner M, Maechler H, Kappe CO, Glasnov TN, Hoefler G, Braune M, Wittchow E, Groschner K. A TRPC3 blocker, ethyl-1-(4-(2,3,3-trichloroacrylamide)phenyl)-5-(trifluoromethyl)-1H-pyrazole-4-c arboxylate (Pyr3), prevents stentinduced arterial remodeling. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;344:33–40. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.196832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhr FK, Smith KA, Song MY, Levitan I, Yuan JX. New mechanisms of pulmonary arterial hypertension: role of Ca2+ signaling. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1546–H1562. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00944.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen JP. A menage a trois made in heaven: G-protein-coupled receptors, lipids and TRP channels. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:9–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar B, Dreja K, Shah SS, Cheong A, Xu SZ, Sukumar P, Naylor J, Forte A, Cipollaro M, McHugh D, Kingston PA, Heagerty AM, Munsch CM, Bergdahl A, Hultgardh-Nilsson A, Gomez MF, Porter KE, Hellstrand P, Beech DJ. Upregulated TRPC1 channel in vascular injury in vivo and its role in human neointimal hyperplasia. Circ Res. 2006;98:557–563. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000204724.29685.db. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwahara K, Wang Y, McAnally J, Richardson JA, Bassel-Duby R, Hill JA, Olson EN. TRPC6 fulfills a calcineurin signaling circuit during pathologic cardiac remodeling. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:3114–3126. doi: 10.1172/JCI27702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan HY, Huang Y, Yao X. Regulation of canonical transient receptor potential isoform 3 (TRPC3) channel by protein kinase G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2625–2630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304471101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leypold BG, Yu CR, Leinders-Zufall T, Kim MM, Zufall F, Axel R. Altered sexual and social behaviors in trp2 mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6376–6381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082127599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin MJ, Leung GP, Zhang WM, Yang XR, Yip KP, Tse CM, Sham JS. Chronic hypoxia-induced upregulation of store-operated and receptor-operated Ca2+ channels in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells: a novel mechanism of hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Circ Res. 2004;95:496–505. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000138952.16382.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Chen F, Zhang J, Wang T, Wei X, Wu J, Feng Y, Dai Z, Wu Q. Neuroprotective effect of resveratrol on ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats through TRPC6/CREB pathways. J Mol Neurosci. 2013;50:504–513. doi: 10.1007/s12031-013-9977-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Maier A, Scholze A, Rauch U, Boltzen U, Zhao Z, Zhu Z, Tepel M. High glucose enhances transient receptor potential channel canonical type 6-dependent calcium influx in human platelets via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:746–751. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.162222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Scholze A, Zhu Z, Krueger K, Thilo F, Burkert A, Streffer K, Holz S, Harteneck C, Zidek W, Tepel M. Transient receptor potential channels in essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1105–1114. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000226201.73065.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Yang D, He H, Chen X, Cao T, Feng X, Ma L, Luo Z, Wang L, Yan Z, Zhu Z, Tepel M. Increased transient receptor potential canonical type 3 channels in vasculature from hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2009;53:70–76. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.116947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DY, Scholze A, Kreutz R, Wehland-von-Trebra M, Zidek W, Zhu ZM, Tepel M. Monocytes from spontaneously hypertensive rats show increased store-operated and second messenger-operated calcium influx mediated by transient receptor potential canonical Type 3 channels. Am J Hypertens. 2007a;20:1111–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DY, Thilo F, Scholze A, Wittstock A, Zhao ZG, Harteneck C, Zidek W, Zhu ZM, Tepel M. Increased store-operated and 1-oleoyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol-induced calcium influx in monocytes is mediated by transient receptor potential canonical channels in human essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 2007b;25:799–808. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32803cae2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Yang L, Chen KH, Sun HY, Jin MW, Xiao GS, Wang Y, Li GR. SKF-96365 blocks human ether-a-go-go-related gene potassium channels stably expressed in HEK 293 cells. Pharmacol Res. 2016;104:61–69. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XR, Zhang MF, Yang N, Liu Q, Wang RX, Cao YN, Yang XR, Sham JS, Lin MJ. Enhanced store-operated Ca2+ entry and TRPC channel expression in pulmonary arteries of monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2012;302:C77–C87. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00247.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loga F, Domes K, Freichel M, Flockerzi V, Dietrich A, Birnbaumer L, Hofmann F, Wegener JW. The role of cGMP/cGKI signalling and Trpc channels in regulation of vascular tone. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;100:280–287. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Ran P, Zhang D, Peng G, Li B, Zhong N, Wang J. Sildenafil inhibits chronically hypoxic upregulation of canonical transient receptor potential expression in rat pulmonary arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C114–C123. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00629.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Wang J, Shimoda LA, Sylvester JT. Differences in STIM1 and TRPC expression in proximal and distal pulmonary arterial smooth muscle are associated with differences in Ca2+ responses to hypoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295:L104–L113. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00058.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier T, Follmann M, Hessler G, Kleemann HW, Hachtel S, Fuchs B, Weissmann N, Linz W, Schmidt T, Lohn M, Schroeter K, Wang L, Rutten H, Strubing C. Discovery and pharmacological characterization of a novel potent inhibitor of diacylglycerol-sensitive TRPC cation channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:3650–3660. doi: 10.1111/bph.13151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malczyk M, Veith C, Fuchs B, Hofmann K, Storch U, Schermuly RT, Witzenrath M, Ahlbrecht K, Fecher-Trost C, Flockerzi V, Ghofrani HA, Grimminger F, Seeger W, Gudermann T, Dietrich A, Weissmann N. Classical transient receptor potential channel 1 in hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:1451–1459. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201307-1252OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merritt JE, Armstrong WP, Benham CD, Hallam TJ, Jacob R, Jaxa-Chamiec A, Leigh BK, McCarthy SA, Moores KE, Rink TJ. SK&F 96365, a novel inhibitor of receptor-mediated calcium entry. Biochem J. 1990;271:515–522. doi: 10.1042/bj2710515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minke B. TRP channels and Ca2+ signaling. Cell Calcium. 2006;40:261–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C. Drosophila TRP channels. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:19–28. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1426-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C, Birnbaumer L, Flockerzi V, Bindels RJ, Bruford EA, Caterina MJ, Clapham DE, Harteneck C, Heller S, Julius D, Kojima I, Mori Y, Penner R, Prawitt D, Scharenberg AM, Schultz G, Shimizu N, Zhu MX. A unified nomenclature for the superfamily of TRP cation channels. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:229–231. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00448-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima H, Kumagai K. Reverse-remodeling effects of angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker in a canine atrial fibrillation model. Circ J. 2007;71:1977–1982. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama H, Wilkin BJ, Bodi I, Molkentin JD. Calcineurin-dependent cardiomyopathy is activated by TRPC in the adult mouse heart. FASEB J. 2006;20:1660–1670. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5560com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattel S. From guidelines to bench: implications of unresolved clinical issues for basic investigations of atrial fibrillation mechanisms. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng LC, Gurney AM. Store-operated channels mediate Ca2+ influx and contraction in rat pulmonary artery. Circ Res. 2001;89:923–929. doi: 10.1161/hh2201.100315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Owsianik G, Voets T, Peters JA. Transient receptor potential cation channels in disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:165–217. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Voets T. TRP channels: a TR(I)P through a world of multifunctional cation channels. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1462-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohba T, Watanabe H, Murakami M, Takahashi Y, Iino K, Kuromitsu S, Mori Y, Ono K, Iijima T, Ito H. Upregulation of TRPC1 in the development of cardiac hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohga K, Takezawa R, Arakida Y, Shimizu Y, Ishikawa J. Characterization of YM-58483/BTP2, a novel store-operated Ca2+ entry blocker, on T cell-mediated immune responses in vivo. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:1787–1792. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Inoue R, Yamazaki K, Maeda A, Kurosaki T, Yamakuni T, Tanaka I, Shimizu S, Ikenaka K, Imoto K, Mori Y. Molecular and functional characterization of a novel mouse transient receptor potential protein homologue TRP7. Ca2+-permeable cation channel that is constitutively activated and enhanced by stimulation of G protein-coupled receptor. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27359–27370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.39.27359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onohara N, Nishida M, Inoue R, Kobayashi H, Sumimoto H, Sato Y, Mori Y, Nagao T, Kurose H. TRPC3 and TRPC6 are essential for angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy. EMBO J. 2006;25:5305–5316. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipp S, Wissenbach U, Flockerzi V. Molecular biology of calcium channels. In: Putney JWJ, editor. Calcium Signaling. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2000. pp. 321–342. [Google Scholar]

- Piper HM, Abdallah Y, Schafer C. The first minutes of reperfusion: a window of opportunity for cardioprotection. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant TD, Schaefer M. TRPC4 and TRPC5: receptor-operated Ca2+-permeable nonselective cation channels. Cell Calcium. 2003;33:441–450. doi: 10.1016/S0143-4160(03)00055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteser M, Graziani A, Rosker C, Eder P, Derler I, Kahr H, Zhu MX, Romanin C, Groschner K. TRPC3 and TRPC4 associate to form a redox-sensitive cation channel. Evidence for expression of native TRPC3-TRPC4 heteromeric channels in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13588–13595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putney JW., Jr A model for receptor-regulated calcium entry. Cell Calcium. 1986;7:1–12. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(86)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio A, Medhurst AD, Mattei C, Kelsell RE, Calver AR, Randall AD, Benham CD, Pangalos MN. mRNA distribution analysis of human TRPC family in CNS and peripheral tissues. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;109:95–104. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(02)00527-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum MA, Chaudhuri P, Graham LM. Hypercholesterolemia inhibits re-endothelialization of arterial injuries by TRPC channel activation. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62:1040–1047.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell J, Koitabashi N, Kass DA. TRP-ing up heart and vessels: canonical transient receptor potential channels and cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2010;3:516–524. doi: 10.1007/s12265-010-9208-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabourin J, Robin E, Raddatz E. A key role of TRPC channels in the regulation of electromechanical activity of the developing heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;92:226–236. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh S, Tanaka H, Ueda Y, Oyama J, Sugano M, Sumimoto H, Mori Y, Makino N. Transient receptor potential (TRP) protein 7 acts as a G protein-activated Ca2+ channel mediating angiotensin II-induced myocardial apoptosis. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;294:205–215. doi: 10.1007/s11010-006-9261-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M, Plant TD, Obukhov AG, Hofmann T, Gudermann T, Schultz G. Receptor-mediated regulation of the nonselective cation channels TRPC4 and TRPC5. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17517–17526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.23.17517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleifer H, Doleschal B, Lichtenegger M, Oppenrieder R, Derler I, Frischauf I, Glasnov TN, Kappe CO, Romanin C, Groschner K. Novel pyrazole compounds for pharmacological discrimination between receptor-operated and store-operated Ca2+ entry pathways. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167:1712–1722. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo K, Rainer PP, Shalkey Hahn V, Lee DI, Jo SH, Andersen A, Liu T, Xu X, Willette RN, Lepore JJ, Marino JP, Jr, Birnbaumer L, Schnackenberg CG, Kass DA. Combined TRPC3 and TRPC6 blockade by selective small-molecule or genetic deletion inhibits pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:1551–1556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308963111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seth M, Zhang ZS, Mao L, Graham V, Burch J, Stiber J, Tsiokas L, Winn M, Abramowitz J, Rockman HA, Birnbaumer L, Rosenberg P. TRPC1 channels are critical for hypertrophic signaling in the heart. Circ Res. 2009;105:1023–1030. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.206581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan D, Marchase RB, Chatham JC. Overexpression of TRPC3 increases apoptosis but not necrosis in response to ischemia-reperfusion in adult mouse cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2008;294:C833–C841. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00313.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaywitz AJ, Greenberg ME. CREB: a stimulus-induced transcription factor activated by a diverse array of extracellular signals. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:821–861. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Ju M, Abramowitz J, Large WA, Birnbaumer L, Albert AP. TRPC1 proteins confer PKC and phosphoinositol activation on native heteromeric TRPC1/C5 channels in vascular smooth muscle: comparative study of wild-type and Trpc1−/− mice. FASEB J. 2012;26:409–419. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-185611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Miralles F, Birnbaumer L, Large WA, Albert AP. Store depletion induces Galphaq-mediated PLCbeta1 activity to stimulate TRPC1 channels in vascular smooth muscle cells. FASEB J. 2016;30:702–715. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-280271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short AD, Bian J, Ghosh TK, Waldron RT, Rybak SL, Gill DL. Intracellular Ca2+ pool content is linked to control of cell growth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90:4986–4990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.4986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedlund K, Tano JY, Vazquez G. The constitutive function of native TRPC3 channels modulates vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in coronary endothelial cells through nuclear factor κB signaling. Circ Res. 2010;106:1479–1488. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.213314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedlund K, Vazquez G. Involvement of native TRPC3 proteins in ATP-dependent expression of VCAM-1 and monocyte adherence in coronary artery endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:2049–2055. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.175356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedlund KB, Birnbaumer L, Vazquez G. Increased size and cellularity of advanced atherosclerotic lesions in mice with endothelial overexpression of the human TRPC3 channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:E2201–E2206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505410112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soboloff J, Spassova M, Xu W, He LP, Cuesta N, Gill DL. Role of endogenous TRPC6 channels in Ca2+ signal generation in A7r5 smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39786–39794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506064200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowers L, Holy TE, Meister M, Dulac C, Koentges G. Loss of sex discrimination and male-male aggression in mice deficient for TRP2. Science. 2002;295:1493–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1069259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabas I, Tall A, Accili D. The impact of macrophage insulin resistance on advanced atherosclerotic plaque progression. Circ Res. 2010;106:58–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai Y, Feng S, Ge R, Du W, Zhang X, He Z, Wang Y. TRPC6 channels promote dendritic growth via the CaMKIV-CREB pathway. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:2301–2307. doi: 10.1242/jcs.026906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi S, Lin H, Geshi N, Mori Y, Kawarabayashi Y, Takami N, Mori MX, Honda A, Inoue R. Nitric oxide-cGMP-protein kinase G pathway negatively regulates vascular transient receptor potential channel TRPC6. J Physiol. 2008;586:4209–4223. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.156083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Watanabe H, Murakami M, Ohba T, Radovanovic M, Ono K, Iijima T, Ito H. Involvement of transient receptor potential canonical 1 (TRPC1) in angiotensin II-induced vascular smooth muscle cell hypertrophy. Atherosclerosis. 2007;195:287–296. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tano JY, Lee RH, Vazquez G. Macrophage function in atherosclerosis: potential roles of TRP channels. Channels (Austin) 2012;6:141–148. doi: 10.4161/chan.20292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauseef M, Farazuddin M, Sukriti S, Rajput C, Meyer JO, Ramasamy SK, Mehta D. Transient receptor potential channel 1 maintains adherens junction plasticity by suppressing sphingosine kinase 1 expression to induce endothelial hyperpermeability. FASEB J. 2016;30:102–110. doi: 10.1096/fj.15-275891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thilo F, Loddenkemper C, Berg E, Zidek W, Tepel M. Increased TRPC3 expression in vascular endothelium of patients with malignant hypertension. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:426–430. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth P, Csiszar A, Tucsek Z, Sosnowska D, Gautam T, Koller A, Schwartzman ML, Sonntag WE, Ungvari Z. Role of 20-HETE, TRPC channels, and BKCa in dysregulation of pressure-induced Ca2+ signaling and myogenic constriction of cerebral arteries in aged hypertensive mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305:H1698–H1708. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00377.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatachalam K, Zheng F, Gill DL. Regulation of canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) channel function by diacylglycerol and protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29031–29040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302751200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakili R, Voigt N, Kaab S, Dobrev D, Nattel S. Recent advances in the molecular pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2955–2968. doi: 10.1172/JCI46315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Fu X, Yang K, Jiang Q, Chen Y, Jia J, Duan X, Wang EW, He J, Ran P, Zhong N, Semenza GL, Lu W. Hypoxia inducible factor-1-dependent up-regulation of BMP4 mediates hypoxia-induced increase of TRPC expression in PASMCs. Cardiovasc Res. 2015;107:108–118. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Jiang Q, Wan L, Yang K, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Wang E, Lai N, Zhao L, Jiang H, Sun Y, Zhong N, Ran P, Lu W. Sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate inhibits canonical transient receptor potential expression in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle from pulmonary hypertensive rats. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013a;48:125–134. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0071OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Weigand L, Lu W, Sylvester JT, Semenza GL, Shimoda LA. Hypoxia inducible factor 1 mediates hypoxia-induced TRPC expression and elevated intracellular Ca2+ in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2006;98:1528–1537. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000227551.68124.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZT, Wang Z, Hu YW. Possible roles of platelet-derived microparticles in atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2016;248:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber EW, Han F, Tauseef M, Birnbaumer L, Mehta D, Muller WA. TRPC6 is the endothelial calcium channel that regulates leukocyte transendothelial migration during the inflammatory response. J Exp Med. 2015;212:1883–1899. doi: 10.1084/jem.20150353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh DG, Morielli AD, Nelson MT, Brayden JE. Transient receptor potential channels regulate myogenic tone of resistance arteries. Circ Res. 2002;90:248–250. doi: 10.1161/hh0302.105662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn MP, Conlon PJ, Lynn KL, Farrington MK, Creazzo T, Hawkins AF, Daskalakis N, Kwan SY, Ebersviller S, Burchette JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Howell DN, Vance JM, Rosenberg PB. A mutation in the TRPC6 cation channel causes familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Science. 2005;308:1801–1804. doi: 10.1126/science.1106215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Eder P, Chang B, Molkentin JD. TRPC channels are necessary mediators of pathologic cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7000–7005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001825107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuensch T, Thilo F, Krueger K, Scholze A, Ristow M, Tepel M. High glucose-induced oxidative stress increases transient receptor potential channel expression in human monocytes. Diabetes. 2010;59:844–849. doi: 10.2337/db09-1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Yang XR, Fu Z, Paudel O, Abramowitz J, Birnbaumer L, Sham JS. Classical transient receptor potential 1 and 6 contribute to hypoxic pulmonary hypertension through differential regulation of pulmonary vascular functions. Hypertension. 2014;63:173–180. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu SZ, Beech DJ. TrpC1 is a membrane-spanning subunit of store-operated Ca2+ channels in native vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 2001;88:84–87. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.88.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Fantozzi I, Remillard CV, Landsberg JW, Kunichika N, Platoshyn O, Tigno DD, Thistlethwaite PA, Rubin LJ, Yuan JX. Enhanced expression of transient receptor potential channels in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13861–13866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405908101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue Z, Xie J, Yu AS, Stock J, Du J, Yue L. Role of TRP channels in the cardiovascular system. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;308:H157–H182. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00457.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Remillard CV, Fantozzi I, Yuan JX. ATP-induced mitogenesis is mediated by cyclic AMP response element-binding protein-enhanced TRPC4 expression and activity in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C1192–C1201. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00158.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Lu W, Yang K, Xu L, Lai N, Tian L, Jiang Q, Duan X, Chen M, Wang J. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 decreases TRPC expression, store-operated Ca2+ entry, and basal [Ca2+]i in rat distal pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol, Cell Physiol. 2013;304:C833–C843. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00036.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Wang Y, Yang K, Tian L, Fu X, Wang Y, Sun Y, Jiang Q, Lu W, Wang J. BMP4 increases the expression of TRPC and basal [Ca2+]i via the p38MAPK and ERK1/2 pathways independent of BMPRII in PASMCs. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e112695. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu DY, Lau L, Liu SH, Wei JS, Lu YM. Activation of cAMP-response-element-binding protein (CREB) after focal cerebral ischemia stimulates neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9453–9457. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401063101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Chu PB, Peyton M, Birnbaumer L. Molecular cloning of a widely expressed human homologue for the Drosophila trp gene. FEBS Lett. 1995;373:193–198. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01038-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]