Abstract

Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase beta (IKKβ) plays a critical role in cell proliferation and inflammation in various cells by activating NF-κB signaling. However, the interrelationship between peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα) and IKKβ in cell proliferation is not clear. In this study, we investigated the possible role of PPARα in the hepatic cell death in the absence of IKKβ gene using liver-specific Ikkb-null (IkkbF/F-AlbCre) mice. To examine the function of PPARα activation in hepatic cell death, wild-type (IkkbF/F) and IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice were treated with PPARα agonist Wy-14,643 (0.1% w/w chow diet) for two weeks. As a result of Wy-14,643 treatment, apoptotic markers including caspase-3 cleavage, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage and TUNEL-positive staining were significantly decreased in the IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice. Surprisingly, Wy-14,643 increased the phosphorylation of p65 and STAT3 in both Ikkb and IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice. Furthermore, BrdU-positive cells were significantly increased in both groups after treatment with Wy-14,643. Our results suggested that IKKβ-derived hepatic apoptosis could be altered by PPARα activation in conjunction with activation of NF-κB and STAT3 signaling.

Keywords: PPARa; IKKb; NF-kB; Wy-14,643; STAT3

INTRODUCTION

The inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase (IKK) complex consists of three core elements including two kinases (IKKα, IKKβ) and a regulatory subunit (IKKγ), and plays a critical role in inflammation, cell survival, tumorigenesis, and immune responses (Baldwin, 2012; Liu et al., 2012). IKKβ is a major kinase that regulates nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) activation in response to pro-inflammatory and many other stress stimuli by triggering phosphorylation and degradation of the NF-κB inhibitor I-κB (Hayden and Ghosh, 2004). Previously, the function of IKKβ was studied using Ikkb null mice, which showed embryonic lethality at approximately day E13 due to massive liver apoptosis (Li et al., 1999a, 1999b). Thus, hepatic IKKβ has been regarded a major factor in hepatic cell death.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily, is a ligand-activated transcription factor having a critical role in the regulation of lipid metabolism, inflammation, and carcinogenesis in the liver (Pyper et al., 2010; Peters et al., 2012). As an adaptive response, PPARα can be activated by starvation in the liver where it induces genes involved in fatty acid transport and β-oxidation, and gluconeogenesis (Kersten et al., 1999). PPARα is activated by endogenous fatty acid metabolites such as phosphatidyl choline and fibrates (synthetic PPARα ligands) used for the treatment of hyperlipidemia in humans. Following ligand binding, PPARα heterodimerizes with retinoid X receptor alpha (RXRα) at specific DNA-response elements known as peroxisome proliferator response elements in target genes (Desvergne and Wahli, 1999; Chakravarthy et al., 2009). Prolonged treatment with PPARα agonists could lead to hepatocarcinogenesis and hepatic necrosis in rodents, but not in humans (Peters et al., 1997; Klaunig et al., 2003; Hays et al., 2005; Woods et al., 2007). This may be caused by the oxidative stress induced by PPARα activation because elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS), notably H2O2, are produced during fatty acid β-oxidation. Indeed, the elevated level of oxidative stress by PPARα activation could also induce cell cycle arrest and cell death-related signaling by early induction of p21 and GADD45b. However, the expression of these genes is not sufficient to induce hepatic apoptosis. Thus, there might exist a factor rendering cells resistant against oxidative stress-mediated hepatic apoptosis (Kim et al., 2014). Here, a hepatocyte-specific Ikkb-null mouse model was used to determine whether Ikkb ablation changes the hepatic cell death during PPARα activating period, because IKKβ/NF-κB/STAT3 was implicated in the hepatic cell death or tumor progression in conjunction with oxidative stress.

Although multiple PPARα studies have focused on the mechanisms of lipid metabolism, inflammation, and hepatocarcinogenesis, the effect of the oxidative stress induced by PPARα activation in hepatic cell death has not been mechanistically elucidated. Because PPARα agonists are clinically used for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia, it is important to study the possible outcome of liver cancer using different genetic background mouse models. Thus, in this study, we explored the role of PPARα in hepatic cell death in the absence of IKKβ gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

PPARα agonist Wy-14,643 was a gift from Janardan Reddy, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA. Anti-caspase-3, anti-cleaved PARP, anti-pp65, anti-pBAD and anti-BAD antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Anti-actin antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Anti-p21 antibody was purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). The TUNEL staining kit was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI, USA).

Mice

Seven- to eight-week-old male Ikkb-floxed mice (IkkbF/F) (Maeda et al., 2003), obtained from Michael Karin, University of California, San Diego, CA, USA, on the C57BL/6 background were bred to albumin-Cre recombinase transgenic mice (Yakar et al., 1999) to obtain IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice. The mice were housed in a pathogen-free animal facility under standard 12-h light/dark cycles with water and chow ad libitum. For Wy-14,643 treatment, mice were fed a diet with 0.1% w/w Wy-14,643 (Bio-Serv, Frenchtown, NJ, USA). Mice fed a normal chow diet were used as a control. All experiments were carried out per the guidelines of the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care with approval from the NCI Animal Care and Use Committee.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from frozen/fresh mouse livers using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using a SuperScript II reverse transcriptase kit (Invitrogen). qPCRs were run on a Prism 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). All reactions were performed in a 10-μl volume comprising 25 ng cDNA, 300 nM of each primer, and 5 μl of SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The cycling conditions were 10 min at 95°C and 40 cycles of 95°C for 3 s and 60°C for 30 s. mRNA expression levels were normalized to the Gapdh mRNA level. Primers for qPCR were designed using qPrimerDepot (http://mouseprimerdepot.nci.nih.gov/).

Western blotting

Mouse livers were lysed with RIPA lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Triton X-100, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 25 mM NaF, 20 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM Na3VO4, and protease inhibitor cocktail) for 30 min on ice, followed by centrifugation at 14,800×g for 15 min. Protein concentrations were measured with bicinchoninic acid reagent. Protein (30 μg) was electrophoresed on a 4–15% gradient Tris-HCl gel (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane in Tris-glycine buffer (pH 8.4) containing 20% methanol. The membranes were blocked with 5% fat-free dry milk in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (PBST) for 1 h, and incubated with primary antibodies and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies using standard western blotting procedures. Proteins were visualized using the Femto signal chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific/Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) under an image analyzer (Alpha Innotech Corp., San Leandro, CA, USA).

Histological and immunohistochemical analyses

For microscopic examination, fresh livers were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded with paraffin. Tissue sections (4 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The TUNEL staining kit was used for immunohistochemistry. Frozen liver tissues were cut at 10 μm thickness and stained with Oil O red to detect lipid droplets. For BrdU incorporation experiments, mini-osmotic pumps containing sterile BrdU were implanted subcutaneously and mice were euthanized 6 days later. Then, liver paraffin sections (4 μm) were prepared for immunohistochemistry.

Statistical analysis

Experimental values are expressed as means ± SDs. Statistical analysis was performed by two-tailed Student’s t test, with p<0.05 considered significant.

RESULTS

Ablation of the Ikkβ gene induces hepatic cell death

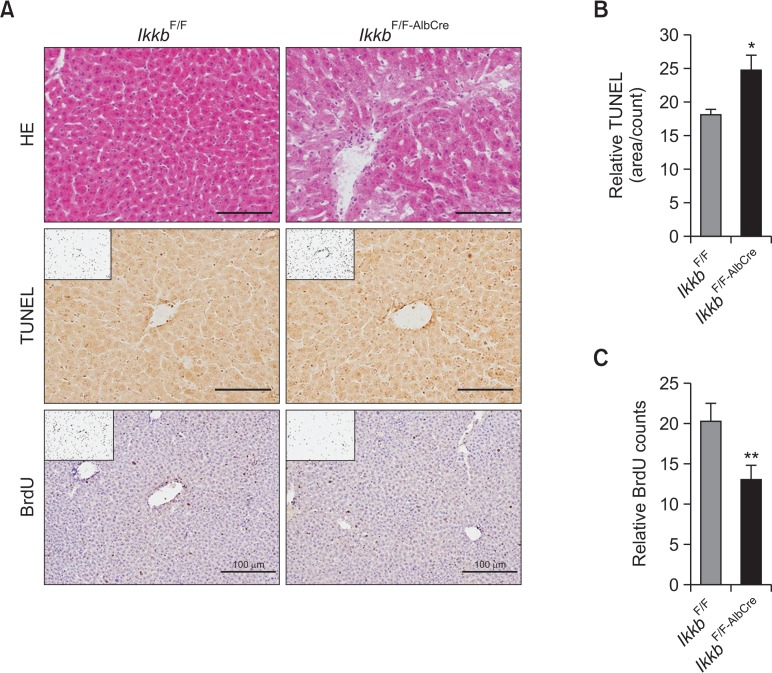

To verify our hepatocyte-specific Ikkb-null mouse model as described in previous reports (Li et al., 1999a, 1999b), the livers from IkkbF/F and IkkbF/F-AlbCre were subjected to histological and immunohistochemical analyses. Histological data showed that there were no specific differences in cell morphological features between the two strains, but the cytosol was weakly stained by eosin in the IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice (Fig. 1A). This might be due to the process of apoptosis. To assess the apoptotic feature in the livers of IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice, apoptotic cells were counted after TUNEL staining; positive, apoptotic cells were significantly increased in the IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice (Fig. 1B). Likewise, BrdU-positive cells were significantly reduced in the livers of IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice when compared to those of IkkbF/F mice (Fig. 1C). In our mouse model, mild hepatic apoptosis was observed in the absence of the Ikkβ gene. Thus, a compensatory mechanism of hepatic cell proliferation may exist.

Fig. 1.

Ablation of the Ikkb gene induces hepatic cell death. (A) Liver samples from IkkbF/F and IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice were subjected to HE, TUNEL, and BrdU staining. (B) TUNEL-positive cells were counted using ImageJ and expressed relative to the control. (C) BrdU-positive cells were counted using ImageJ and expressed relative to the control. *p<0.01; **p<0.001.

PPARα agonist Wy-14,643 ameliorates the hepatic apoptosis in IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice

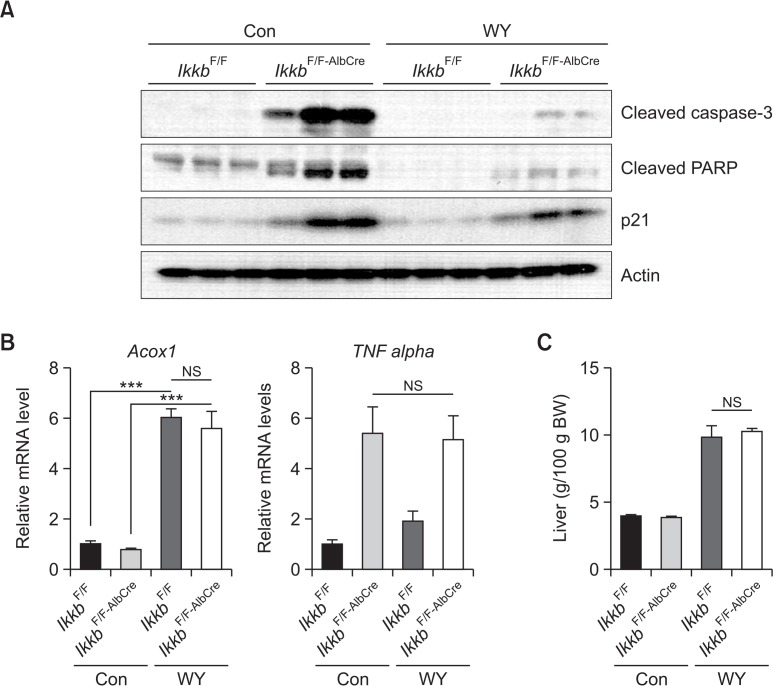

To investigate the potential role of PPARα activation in hepatic apoptosis in the absence of Ikkb, IkkbF/F and IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice were treated with the PPARα agonist Wy-14,643 (0.1% w/w) for two weeks. Wy-14,643 treatment resulted in a decrease in apoptotic markers cleaved-caspase-3 and cleaved-PARP, and the cell cycle inhibitory protein p21 in the livers of IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice (Fig. 2A). Thus, PPARα activation may abolish the Ikkβ-derived cell death by stimulating proliferation signals. For control of PPARα activation by Wy-14,643, the expression of Acox1 (acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1, palmitoyl) mRNA (Fig. 2B) and liver weight (Fig. 2C) were measured in both groups. As results, massive induction of Acox1 mRNA and hepatomegaly were similarly induced by Wy-14,643 in both groups. To check whether TNFα is involved in the hepatic apoptosis, we measured the hepatic TNFα mRNA level in the IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice after Wy-14,643 treatment. However, we observed no change in TNFα mRNA in the livers of IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice after Wy-14,643 treatment (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Wy-14,643 inhibits hepatic apoptosis in Ikkb conditional knockout mice. (A) IkkbF/F and IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice were treated with Wy-14,643 (0.1%, w/w) for 2 weeks. Liver samples were subjected to western blot analysis. Con, control diet; WY, Wy-14,643. (B) The samples from (A) were subjected to qPCR. (C) Liver weights from IkkbF/F and IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice measured after Wy-14,643 treatment. ***p<0.0001; NS, not significant.

Wy-14,643 increases NF-κB and STAT3 phosphorylation and cell proliferation in IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice

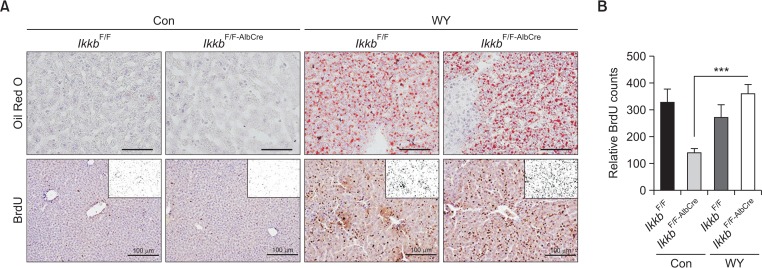

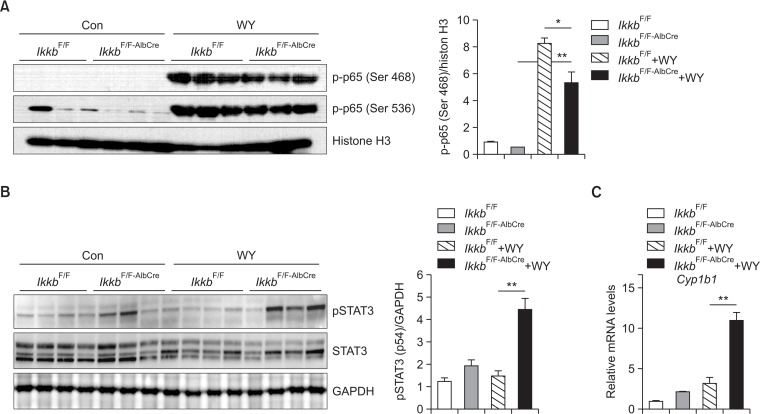

It is widely considered that IKKβ inhibits TNFα-induced apoptosis through the activation of NF-κB (Karin and Ben-Neriah, 2000; Baldwin, 2012). Thus, we measured NF-κB activation in livers of both IkkbF/F and IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice after Wy-14,643 treatment. Because hepatic apoptosis was significantly reduced by PPARα activation in the IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice, we checked cellular proliferation markers such as phosphorylation of p65 and BrdU. As shown in Fig. 3, BrdU-positive cells were significantly increased by treatment with Wy-14,643 in IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice. Because Wy-14,643 induced hepatomegaly with enlarged hepatocyte and nucleus, thus we counted the number of nuclei stained with BrdU. To check PPARα activation by Wy-14,643, lipid droplets were stained using Oil Red O (Fig. 3A). IKKβ deficiency seemingly did not alter Wy-14,643-mediated lipid accumulation. Because NF-κB phosphorylation is important for the cell proliferation, thus we measured phosphorylated p65 by detecting the two different forms of phosphorylation (Ser 468 and Ser536) in the transactivation domain (TAD) (Christian et al., 2016). Interestingly, Wy-14,643 significantly induced the phosphorylation of p65 in the livers of IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice (Fig. 4A). In addition, STAT3 phosphorylation was also dramatically increased in the livers of IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice (Fig. 4B). As shown in the previous report (Kim et al., 2014), STAT3 protein level and its phosphorylation were rather decreased by treatment with Wy-14,643 for 24 h. thus STAT3 activation by Wy-14,643 in the absence of IKKβ is novel feature in this study. Furthermore, Cyp1b1 mRNA was strongly induced only IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice after Wy-14,643 treatment (Fig. 4C). This might be due to the activation of STAT3 (Patel et al., 2014).

Fig. 3.

Wy-14,643 strongly induces cell proliferation marker, BrdU, in the livers of both IkkbF/F and IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice. (A) IkkbF/F and IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice were treated with Wy-14,643 (0.1%, w/w) for 2 weeks. Liver samples were subjected to BrdU staining for evaluation of cell proliferation. Lipid droplets were stained with Oil Red O dye to check for the induction of lipogenesis in mice fed the Wy-14,643 diet. (B) The relative BrdU counts from (A) were measured using ImageJ program. ***p<0.0001.

Fig. 4.

Wy-14,643 strongly induces cell proliferation markers, p-p65 and pSTAT3, in the livers of both IkkbF/F and IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice. IkkbF/F and IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice were treated with Wy-14,643 (0.1%, w/w) for 2 weeks. Protein extracts from nuclei or whole cells were subjected to Western blotting. (A) The nuclear p-p65(Ser 468 or Ser 536) protein was measured. Histone H3 was used as an equal loading control. Densitometric analysis of p-p65 (Ser 468) was shown in the right panel. (B) pSTAT3 protein was detected using whole cell lysate. GAPDH was used as an equal loading control. Densitometric analysis of pSTAT3 was shown in the right panel. (C) Hepatic Cyp1b1 mRNA was measured using real-time PCR method. Con, Control diet; WY, Wy-14,643. *p<0.05; **p<0.001.

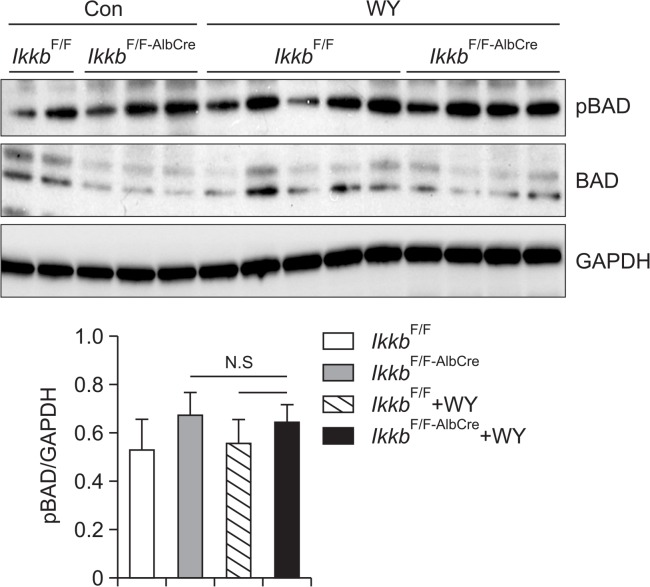

Bcl-2-associated death promoter (BAD) is independent of Wy-14,643-induced cell proliferation in IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice

Based on a previous report, the activity of BAD was inhibited by IKKβ on the TNFα-induced apoptosis (Yan et al., 2013). Thus we checked the level of active BAD protein whether BAD could affect the hepatic proliferation by Wy-14,643 in the absence of IKKβ gene. The results showed that phosphorylated BAD was not significantly altered by Wy-14,643 in both IkkbF/F and IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice (Fig. 5) indicating that BAD may not involve in the Wy-14,643-induced hepatic cell proliferation.

Fig. 5.

BAD, an anti-apoptotic protein, showed no significant change on its activation by Wy-14,643 treatment in Ikkβ conditional knock-out mice. IkkbF/F and IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice were treated with Wy-14,643 (0.1%, w/w) for 2 weeks. Liver samples were subjected to Western blotting analysis for detection of p-BAD protein. The p-BAD proteins were analyzed using a densitometer. Con, Control diet; WY, Wy-14,643; N.S, Not significant.

DISCUSSION

It has been previously suggested that TNFα can sensitize mice to Ikkβ-mediated embryonic liver cell death, because the embryonic lethality was rescued by crossing Ikkb-null mice with Tnfα-null mice (Li et al., 1999a). However, Wy-14,643 did not alter the Tnfα expression level in the liver of IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice. This suggests that protective effect of Wy-14,643 on hepatic apoptosis is not derived from the change of TNFα signaling.

IKKβ is regarded an important factor in NF-κB-related signaling. However, a previous study revealed that hepatic ablation of Ikkb did not alter NF-κB activation in the presence of TNFα (Luedde et al., 2005). The present study corroborated that adult hepatocyte-specific disruption of Ikkb did not alter NF-κB activation. However, it showed that NF-κB activation was triggered by PPARα, even in the absence of the IKKβ gene. This might indicate that hepatic cell death is reduced by activation of the proliferative signaling such as NF-κB and STAT3 pathways. Because transcription factor NF-κB and STAT3 are collaboratively activated in many cancer cells, this partnership may play an important role in cell survival, proliferation and inflammation (Lee et al., 2009; Kundu and Surh, 2012; Choi et al., 2014). Also, unphosphorylated STAT3 can directly interact with NF-κB and modulate NF-κB target genes, such as RANTES (Yang et al., 2007). In addition, STAT3-drived signaling is required to sustain the level of NF-κB for up-regulation of anti-apoptotic genes and oncogenes which may assist the microenvironment for cancer (Lee et al., 2009). Furthermore, in the normal condition, Wy-14,643 is prone to decreasing STAT3 level and its activation, however, STAT3 activation was solely increased in the liver of IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice by Wy-14,643. The results indicate that oxidative-stress induced STAT3 activation may affect to hepatic proliferation in conjunction with IKKβ/NF-κB pathways (He et al., 2010). As shown in Fig. 4C, Cyp1b1 mRNA, a possible STAT3 target gene, was strongly induced only in the liver of IkkbF/F-AlbCre mice by Wy-14,643. This might be related to STAT3 activation. Thus, it is possible that PPARα-induced oxidative stress might lead to STAT3 activation resulted in reduction of apoptotic signaling or induction of proliferative signaling.

PPARα plays a critical role in lipid metabolism by inducing genes related to fatty acid transporter, β-oxidation and gluconeogenesis. Additionally prolonged exposure with PPARα agonist could induce carcinogenesis in the murine liver. This might be due to the unbalanced oxidative stress. Increased oxidative stress might be produced by the induction of ACOX1 by PPARα activation. ACOX1 is a peroxisomal enzyme involved in the β-oxidation of long-chain and very-long chain fatty acids. During this process, H2O2 is produced as a byproduct (Varanasi et al., 1994). Thus, sustained activation of PPARα may increase cellular oxidative stress. Forced ACOX1 expression in the liver increased Gadd45b, encoding a sensor protein involved in cell cycle arrest which is modulated by H2O2. However, Acox1-null mice showed no induction of Gadd45b or other PPARα target genes, such as Acsl1, Cyp4a10, and Acadm, by Wy-14,643 (Kim et al., 2014). Thus, prolonged exposure with oxidative stress could induce hepatic carcinogenesis by triggering the activation of STAT3 and NF-κB pathway in the absence of Ikkβ gene.

Although PPARα agonists, such as fenofibrate and fibrates of other classes, are used for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia and hypertriglyceridemia, the possibility of adverse effects should be considered, because long-term use of PPARα agonist induces liver cancer in rodents. In a similar context, genetic variation of other gene, such as IKKβ, must be considered for clinic use when PPARα agonist treated to human.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MEST) (NRF-2015R1A5A2008833) and the National Cancer Institute Intramural Research Program. We thank Michael Karin for the Ikkb-floxed mice.

REFERENCES

- Baldwin AS. Regulation of cell death and autophagy by IKK and NF-κB: critical mechanisms in immune function and cancer. Immunol Rev. 2012;246:327–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarthy MV, Lodhi IJ, Yin L, Malapaka RR, Xu HE, Turk J, Semenkovich CF. Identification of a physiologically relevant endogenous ligand for PPARα in liver. Cell. 2009;138:476–488. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y, Kim JK, Yoo JY. NFκB and STAT3 synergistically activate the expression of FAT10, a gene counteracting the tumor suppressor p53. Mol Oncol. 2014;8:642–655. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian F, Smith EL, Carmody RJ. The regulation of NF-κB subunits by phosphorylation. Cells. 2016;5:E12. doi: 10.3390/cells5010012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desvergne B, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: nuclear control of metabolism. Endocr Rev. 1999;20:649–688. doi: 10.1210/edrv.20.5.0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Signaling to NF-κB. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2195–2224. doi: 10.1101/gad.1228704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays T, Rusyn I, Burns AM, Kennett MJ, Ward JM, Gonzalez FJ, Peters JM. Role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPARα) in bezafibrate-induced hepatocarcinogenesis and cholestasis. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:219–227. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He G, Yu GY, Temkin V, Ogata H, Kuntzen C, Sakurai T, Sieghart W, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Leffert HL, Karin M. Hepatocyte IKKβ/NF-κB inhibits tumor promotion and progression by preventing oxidative stress-driven STAT3 activation. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:286–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin M, Ben-Neriah Y. Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[κ]B activity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersten S, Seydoux J, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, Desvergne B, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α mediates the adaptive response to fasting. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:1489–1498. doi: 10.1172/JCI6223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Qu A, Reddy JK, Gao B, Gonzalez FJ. Hepatic oxidative stress activates the Gadd45b gene by way of degradation of the transcriptional repressor STAT3. Hepatology. 2014;59:695–704. doi: 10.1002/hep.26683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaunig JE, Babich MA, Baetcke KP, Cook JC, Corton JC, David RM, DeLuca JG, Lai DY, McKee RH, Peters JM, Roberts RA, Fenner-Crisp PA. PPARα agonist-induced rodent tumors: modes of action and human relevance. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2003;33:655–780. doi: 10.1080/713608372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundu JK, Surh YJ. Emerging avenues linking inflammation and cancer. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:2013–2037. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, Herrmann A, Deng JH, Kujawski M, Niu G, Li Z, Forman S, Jove R, Pardoll DM, Yu H. Persistently activated Stat3 maintains constitutive NF-κB activity in tumors. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Van Antwerp D, Mercurio F, Lee KF, Verma IM. Severe liver degeneration in mice lacking the IκB kinase 2 gene. Science. 1999a;284:321–325. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5412.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZW, Chu W, Hu Y, Delhase M, Deerinck T, Ellisman M, Johnson R, Karin M. The IKKβ subunit of IκB kinase (IKK) is essential for nuclear factor κB activation and prevention of apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1999b;189:1839–1845. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Xia Y, Parker AS, Verma IM. IKK biology. Immunol Rev. 2012;246:239–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01107.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luedde T, Assmus U, Wustefeld T, Meyer zu Vilsendorf A, Roskams T, Schmidt-Supprian M, Rajewsky K, Brenner DA, Manns MP, Pasparakis M, Trautwein C. Deletion of IKK2 in hepatocytes does not sensitize these cells to TNF-induced apoptosis but protects from ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:849–859. doi: 10.1172/JCI23493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda S, Chang L, Li ZW, Luo JL, Leffert H, Karin M. IKKβ is required for prevention of apoptosis mediated by cell-bound but not by circulating TNFα. Immunity. 2003;19:725–737. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SA, Bhambra U, Charalambous MP, David RM, Edwards RJ, Lightfoot T, Boobis AR, Gooderham NJ. Interleukin-6 mediated upregulation of CYP1B1 and CYP2E1 in colorectal cancer involves DNA methylation, miR27b and STAT3. Br. J. Cancer. 2014;111:2287–2296. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JM, Cattley RC, Gonzalez FJ. Role of PPAR α in the mechanism of action of the nongenotoxic carcinogen and peroxisome proliferator Wy-14,643. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:2029–2033. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.11.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JM, Shah YM, Gonzalez FJ. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in carcinogenesis and chemoprevention. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12:181–195. doi: 10.1038/nrc3214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyper SR, Viswakarma N, Yu S, Reddy JK. PPARα: energy combustion, hypolipidemia, inflammation and cancer. Nucl Recept Signal. 2010;8:e002. doi: 10.1621/nrs.08002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varanasi U, Chu R, Chu S, Espinosa R, LeBeau MM, Reddy JK. Isolation of the human peroxisomal acyl-CoA oxidase gene: organization, promoter analysis, and chromosomal localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3107–3111. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods CG, Burns AM, Bradford BU, Ross PK, Kosyk O, Swenberg JA, Cunningham ML, Rusyn I. WY-14,643 induced cell proliferation and oxidative stress in mouse liver are independent of NADPH oxidase. Toxicol Sci. 2007;98:366–374. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakar S, Liu JL, Stannard B, Butler A, Accili D, Sauer B, LeRoith D. Normal growth and development in the absence of hepatic insulin-like growth factor I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:7324–7329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Xiang J, Lin Y, Ma J, Zhang J, Zhang H, Sun J, Danial NN, Liu J, Lin A. Inactivation of BAD by IKK inhibits TNFα-induced apoptosis independently of NF-κB activation. Cell. 2013;152:304–315. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Liao X, Agarwal MK, Barnes L, Auron PE, Stark GR. Unphosphorylated STAT3 accumulates in response to IL-6 and activates transcription by binding to NFκB. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1396–1408. doi: 10.1101/gad.1553707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]