Abstract

People often view certain ways of classifying people (e.g., by gender, race, or ethnicity) as reflecting real distinctions found in nature. Such categories are viewed as marking meaningful, fundamental, and informative differences between distinct kinds of people. The present paper examines the development of these essentialist intuitive theories of how the social world is structured, along with the developmental consequences of these beliefs. We first examine the processes that give rise to social essentialism, arguing that essentialism emerges as children actively attempt to make sense of their environment by relying on several basic representational and explanatory biases. These developmental processes give rise to the widespread emergence of social essentialist views in early childhood, but allow for vast variability across development and cultural contexts in the precise nature of these beliefs. We then examine what is known and still to be discovered about the implications of essentialism for stereotyping, inter-group interaction, and the development of social prejudice. We conclude with directions for future research, particularly on the theoretical payoff that could be gained by including more diverse samples of children in future developmental investigations.

Introduction

Expecting a young girl growing up in a household of boys to prefer princesses to toy trucks, assuming that African Americans excel at sports because of a particular gene, or believing that liberals and conservatives are fundamentally distinct kinds of people, all reflect an essentialist view of human social organization. The term “psychological essentialism” describes an intuitive theory of how important aspects of the world are structured—in particular, that memberships in certain categories (e.g., tigers, apple trees, girls) are determined by underlying, stable, and causally-powerful “essences,” and therefore that such categories mark real, objective distinctions found in nature that reflect something deep, stable, and informative about category members1,2. Essentialist beliefs shape how people represent and reason about certain aspects of the world from at least the early preschool years3, and contribute to many critical cognitive, social and behavioral processes. The present paper provides an account of how such beliefs arise in the social domain across the course of early childhood development, and describes what is known and what is still to be discovered about the developmental consequences of these beliefs.

DEFINITIONS AND MEASUREMENTS

This paper addresses essentialist beliefs—we are making a claim about human psychology, not a metaphysical claim about the world. There is no question that essentialism provides a scientifically inaccurate description of the world4–6. As illustrations, there is no gene or set of genes that reliably determines an individual’s race or ethnicity7,8; human preferences, abilities, and skills vary widely both within and across categories (e.g.,9); and social categories have fuzzy and flexible—rather than absolute and strict—boundaries that are determined by history and cultural convention, rather than any objective structure in the world (see review in10). In describing social essentialism, we are describing the biased way that people often see and understand the world, not proposing that the world actually has this structure.

It is difficult to directly measure the belief that categories are defined by intrinsic, causally powerful, “essences,” in part because people usually do not have firm ideas about what comprises the “essence” of any particular category. People expect that there must be some intrinsic property that unites category members, without expectations about what that property entails2. Further complicating measurement, psychological essentialism describes an intuitive theory, not detailed or necessarily explicit beliefs; as such, people may not be able to fully articulate their own essentialist intuitions. Direct measurement of essentialism is difficult in adults (although some scales have been used successfully with adult populations,11–13, and is not at all feasible in young children.

Instead, developmental researchers measure specific cognitive consequences of essentialism. There are multiple cognitive implications of essentialism, including beliefs that (a) category boundaries are discrete (e.g., that an individual can be a member of one category or another, but not both, and that individuals are always full members or not members at all), (b) that category boundaries are objective (e.g., that categories mark real distinctions found in nature), (c) that categories mark homogeneous kinds (e.g., that category members share many known and yet-to-be-discovered properties), (d) that category membership is causally powerful (e.g., and thus can explain why individuals have particular properties), and (e) that category membership is intrinsic (e.g., obtained via some unobservable process that was involved in an entity’s creation) and stable across time and environments (see14). A summary of each of these components of essentialism and sample findings of each in the social domain is in Table 1.

Table 1.

Components of essentialist beliefs.

| Essentialist belief | Cognitive consequence | Sample findingsa |

|---|---|---|

| Natural kinds: Categories reflect real distinctions found in nature, instead of conventions that vary across individuals or contexts | Categorization decisions reflect a belief that there is a right-or-wrong way to categorize–children reject categorization decisions made by others that do not follow their expected system of classification | Children (age 5)b say that it is “wrong” for people in a different community with different conventions to call a boy and a girl the “same kind” of person18–21 |

| Children (age 3) assume that a person looking for someone that is the “same kind” as a pictured girl must be searching for another girl, even if one is not pictured in the visible answer choices22,23 | ||

| Strict boundaries: Categories have discrete boundaries | Children predict that properties held by members of one category will not be held by members of another. | Children (age 5) reject the possibility that a girl raised entirely around boys could have both male-stereotypical and female- stereotypical properties24,25 |

| Children judge individual exemplars (even atypical ones) as either full members or not members at all; they reject the possibility of partial memberships. | Children (age 5) respond that atypical examples (e.g., emus for the category BIRD)c are either full members or not members at all, even if they are not sure which it is (they reject the possibility of partial membership;26,2) | |

| Homogeneity: Categories are homogeneous—category members will share properties with one another, even if they have other dissimilarities | Children predict that members of the same category will share nonobvious properties, even if they have different appearances, personalities, or other dissimilarities | Children (age 4) predict that an individual who appears similar to a boy but is labeled as a girl will share nonobvious properties with other girls27–30 |

| Stability: Category membership is intrinsic and stable | Children predict that category memberships are determined by intrinsic processes before birth (e.g., via inheritance) and will be stable across transformations | Children predict that a baby born to parents who speak one language but raised by parents who speak another with grow up to speak the language of their birth parents31 and that the language a person speaks is constant across development and perceptual changes32 |

| Causal: Category memberships cause the development of category-typical properties | Children predict that category members will develop category-typical properties even if raised in an unusual environment | Children (age 4) predict that a girl raised entirely by boys will nevertheless develop stereotypical properties (e.g., preferring tea sets to toy trucks;25,33, see also34). |

| Children explain category-typical properties by reference to the category | Children explain why girls like tea sets simply in terms of the category (e.g., “because she is a girl”;25; also34,35). |

Sample findings are given for gender categories where such findings exist in the literature, and for other categories when not.

Ages given are the youngest age at which the described pattern was documented

To our knowledge this dimension of essentialist beliefs has not been explicitly examined in the social domain, but this component of essentialism is implicated in Gaither et al., who found that children with essentialist beliefs about race had poor memory for racially ambiguous faces (suggesting that they neglected exemplars that appeared to bridge category boundaries)

All of the inter-related beliefs just described (and in more detail in Table 1) can be understood as a consequence of the intuition that category memberships are conferred via intrinsic, stable, and causally powerful “essences.” Thus, one might expect all of these beliefs to cohere, such that they are present or absent in an all-or-none fashion. The empirical literature does not support this description of psychological essentialism, however. There are multiple models and theoretical descriptions of how various components of essentialist beliefs relate to one another (e.g.,11,15,16), which are beyond the scope of this review. Here, it suffices (and is necessary) to say that the measures described in Table 1 capture empirically distinct (though often related) components of essentialism. For instance, it is sometimes the case that people view particular categories as homogeneous and inductively rich, but do not view membership as stable over time (e.g., for age-based groups, such as babies vs. teenagers). Alternately, it is sometimes the case that children and adults view categories as marking objective boundaries, but nevertheless expect the scope of inferences promoted by that category to be more limited (e.g., for gender, where people might view gender as a natural way to categorize people, but nonetheless not view gender as particularly informative regarding a person’s psychological or behavioral properties). Empirically, these are dissociable beliefs, and they appear to be particularly dissociable in early childhood17. These various components also have distinct psychological, behavioral, and social consequences, as will be discussed below.

HOW DOES SOCIAL ESSENTIALISM DEVELOP?

Early theoretical proposals on the origins of social essentialism suggested that essentialism is the product of a particular folk-biological module36–38, evolved to support reasoning about the biological world (e.g., to represent animal species). From this perspective, social kinds can trigger this module, particularly when people are confronted with social kinds that appear to be structured like distinct species. This perspective makes two predictions that are difficult to reconcile with currently available data. First, the various dimensions of essentialist beliefs described in Table 1 should be highly correlated with each other (as they would all be invoked together once a category “triggers” the relevant module). Second, the particular social categories to which children apply essentialist beliefs should be those that appear to be “most like” animal species (e.g., those that are marked by physical properties or show evidence that membership is determined via biological inheritance,37). As discussed above, the various aspects of essentialism do not always cohere in this manner, especially in early childhood17. Further, as discussed below, data also do not support the prediction that the categories that invoke essentialist beliefs are necessarily those that appear most like biological species.

If not from a folk-biological module, from where do essentialist beliefs arise? As discussed by Gelman3, essentialism arises as children construct abstract causal-explanatory theories of their environment by relying on several basic conceptual biases and capacities, which are all firmly in place in the first few years of life. These include the capacities to expect causal determinism39, induce from property clusters40, track identities over time41, distinguish appearance from reality42, and defer to experts43. Causal determinism, for example, leads children to search for causes for commonalities that they observe (or hear described in language;19). From this perspective, upon hearing that, “tigers have stripes,” children search for a cause to explain that commonality. Since no external cause is available (e.g., children know that all tigers do not have their stripes painted on), or perhaps because of a basic conceptual bias to prefer inherent explanations for category features44, they posit that an internal underlying property (e.g., “the essence”) is responsible for the shared feature. Further, Gelman3 proposed that observing property clusters (e.g., that tigers have stripes, are ferocious, and have sharp teeth) can lead children to generate a second-order inference (or over-hypothesis45,46) that tigers—in general—share other observable and non-obvious features with each other as well40. Finally, deference to experts (also referred to as division of linguistic labor) describes children’s tendency to assume that other people who are more expert (e.g., parents, teachers, and so on) know objectively correct ways to label things43,47. To illustrate, a three-year-old recently said to the first author (when describing wholly imaginary entities): “I know the pretend dolphins in daddy’s closet are really mammal-dolphins like you said, and that they breathe outside of the water. But they look like fish-dolphins, so I’m going to pretend that’s what they are.” This child is showing deference to experts (even in his imagination)—the child views the boundaries between animal categories as objective and real (e.g., between mammals and fish), recognizes that appearances can be misleading (e.g., that dolphins can really be mammals, even though they look like fish), and defers to an expert to identify these boundaries (even though he prefers to pretend otherwise). This basic capacity that contributes to language acquisition (an assumption that more expert speakers know the “right” names for things) contributes to the belief that certain categories reflect real distinctions found in nature (e.g., as often discussed in philosophy, that some categories “carve nature at its joints”48–51).

When developing knowledge about the biological world, children’s environment likely triggers most or all of these basic representational and explanatory capacities simultaneously52–54. For a category like tigers, for example, children observe and hear about property clusters with no obvious external cause (thus triggering the over-hypothesis that tigers in general share observable and non-obvious properties that stem from inherent causes) and also hear labels and related linguistic input that would trigger the expectation that tiger is an objective and distinct kind. Over the first few years of life, the process of making sense of the biological world in this manner can lead children to construct a more general framework theory of the domain—that the biological world is composed of discrete, objective kinds that are marked in language, and that members of these categories share an intrinsic causally-powerful entity (i.e., “the essence”) that leads them to have observed and non-obvious commonalities55–57. Once constructed, this domain-specific framework theory can lead children to assume that new biological categories that they encounter will also have this structure. Indeed, by ages three and four, children assume that novel animal categories are richly structured and have discrete boundaries, even if they have very little information about the category and do not know anything about which properties are characteristic of the kind22,58.

From this perspective, as children develop intuitive theories to make sense of the world around them, they rely on each of the capacities described above to understand why things are labeled the way they are, why individuals tend to have particular properties, and why some individuals are grouped together and separately from others in their environment. As children develop causal-explanatory framework theories of how domains of experience are organized, these capacities—and the explanations for experience that they generate—can be pieced together into a fully integrated essentialist theory, as likely happens in the biological domain.

We propose that these same mechanisms underlie the development of essentialist beliefs regarding the social world, but that they might not lead to the same type of fully integrated essentialist theory of the social world due to important differences in the environmental input that children encounter. Unlike the biological domain, for which children’s experiences with categories (e.g., experiences classifying animals and plants in particular ways) are highly stable across time and contexts52–54, social categorization is highly variable. People are categorized by personal characteristics like gender, race, ethnicity, religion, or social status; by psychological features like personality traits, preferences, skills, and abilities; by groups based on specific experiences, goals, or interests; as well as into arbitrary groups within schools or other organizations10. These categories vary in their salience and meaning across contexts (both across different cultures, and also across different social contexts that a child might encounter in daily life). Thus, children are likely to receive much less consistent evidence regarding the structure of the social world (in comparison to evidence regarding the structure of the biological world), including inconsistent input regarding the status of categories (even labeled categories) within that structure.

Instead of a fully integrated essentialist framework theory of the social domain, the interplay between children’s conceptual biases and the environment they encounter may thus instead give rise to partially essentialist explanations for various types of social groupings. For example, particular cues from language (discussed in detail below) could trigger “deference to experts” explanations for some social groupings, thus giving rise to the belief that certain social categories reflect objective distinctions in the world. If, however, children are not exposed (via their own observations or through language, media, and so on) to relevant property clusters, they may not develop the belief that these categories are highly coherent, and thus would fail to use them to structure their social inferences. Alternately, children could observe property clusters within a social kind, and generate the second-order inference that members of the category will have more in common with one another than can be directly observed, but could have access to some other salient casual mechanism for explaining these similarities (e.g., that the members of the category all attend the same school and therefore play together and end up knowing the same things, liking the same activities and so on). In this case, children might view a category as coherent and inductively informative, but not expect such similarities to arise from inherent casual properties (nor expect members to be stable over time, kinds to reflect objective structure, and so on). In this way, children could piece together a more nuanced framework theory of the social domain—an expectation that some, but not all, labeled categories reflect objective structure, and that some (but not all) of these categories are stable over time, that some (but not all) are inductively rich, and so on. In this situation, children would then need to rely on particular types of input to map these expectations onto the particular categories that they encounter. From this perspective, different forms of input may trigger different components of essentialist explanations. The basic conceptual capacities that underlie essentialism shape children’s understanding of the social world, but may often do so in a way that does not entail the fully-fledged and integrated essentialist theory that we find evidence for in the biological domain.

This account makes several key empirical predictions about the development of social essentialist beliefs that are consistent with available evidence. First, young children should require more evidence to develop essentialist beliefs regarding the social than biological domains (due to domain differences in their intuitive framework theories; see59). Second, because basic conceptual biases that emerge at a young age underlie the development of essentialism, social essentialist beliefs should arise early in development. Third, due to the generality of the basic conceptual biases that underlie essentialism, the tendency to hold essentialist beliefs should be widespread across diverse cultures, but due to the also critical role of environmental input, the precise nature and developmental trajectory of these beliefs should show great cross-cultural variability. Evidence supporting each of these claims will be described in turn.

Children require relatively strong cues to develop essentialist beliefs about social kinds

By preschool, children can readily acquire new ways of categorizing people based on simple perceptual cues and novel noun labels (e.g., red group and blue groups) and even show in-group biases based on these arbitrary and novel social divisions60. Yet, children do not develop essentialist beliefs about such groupings unless they receive additional input. For example, when introduced to two new social categories marked by novel noun labels (e.g., tirolis and flurps), children do not expect members of the same category to share preferences, skills, or abilities61,62, nor do they expect such memberships to be stable over time or inherited by birth63. It is not the case that they treat such categories as meaningless—in addition to showing in-group biases based on such trivial dimensions, children also expect group memberships to constrain how members of those categories will behave toward their in-group members and out-group members64,65—but they do not essentialize these categories unless they receive additional input. These findings contrast with children’s responses to novel animal categories. When children are introduced to new animal categories marked by noun labels (e.g., modies and tomas), they assume that category members are homogeneous and distinct kinds even if they have no further information about the properties that are characteristic of the kind22,58.

Children’s responses to novel social categories are sensible given the varied structure of the social world—some social categories marked by labels are important only in very specific contexts (e.g., skin color is an important marker of social group membership – race – in the United States, but is not an informative group marker in all other countries). Thus, it is reasonable to require additional input—beyond a shared noun label—to assume that a particular category reflects fundamental, objective, and stable distinctions between people. One form of input that appears to support the development of these essentialist expectations is a type of linguistic cue that provides a stronger clue than a simple noun label to the presence of a meaningful category—generic language. Generics express statements about abstract categories (e.g., “girls have long hair” “A Frenchman really knows wine” “cows say moo”), instead of referring to specific individuals or subsets66,67. Because generic language communicates regularities regarding abstract kinds, children assume that categories described with generic language are the kinds of categories that are coherent and causally powerful enough to support such generalizations34,35,67–69.

Hearing generic language elicits essentialist beliefs about both animal categories70 and social categories34. Yet, in the absence of generic language, children still endorse essentialist beliefs about new animal categories about half the time70. In contrast, for new ways of grouping people, children reliably reject essentialist beliefs about the new categories in the absence of generic language, and exposure to generics reliably increases such beliefs. In particular, Rhodes et al.34 introduced four-year-old children to a novel category of people that was diverse for gender, race, and age, so that children would not map the novel category onto any group for which they might already hold essentialist beliefs (see Figure 1). First, an experimenter read an illustrated book that presented a novel category (“Zarpies”), which presented 16 individual pictures of Zarpies, one per page, each displaying a unique property. By condition, children heard the property on each page described either with generic language (e.g., “Look at this Zarpie! Zarpies climb fences”), non-generic category labels (e.g., “Look at this Zarpie! This Zarpie climbs fences”), or no labels at all (e.g., “Look at this one! This one climbs fences”).

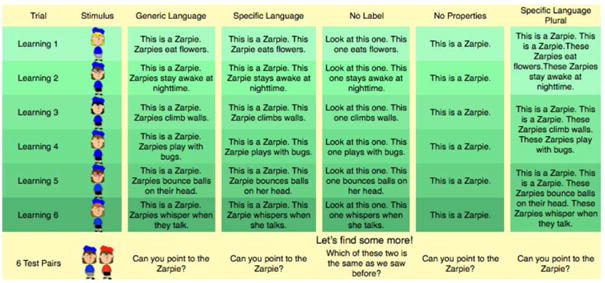

Figure 1.

Sample illustrations of “Zarpies” from Rhodes et al. 2012 [34]. Zarpies were designed to be diverse for sex, race, and age, so that the category would not easily map onto one for which children might already hold essentialist beliefs. During the first phase of the experiment, children were shown 16 individual Zarpies, one at a time. Text accompanied each illustration, which varied by condition. For example: Generic condition: “Look at this Zarpie! Zarpies are scared of ladybugs”; Specific condition: “Look at this Zarpie! This Zarpie is scared of ladybugs”; No label condition: “Look at this one! This one is scared of ladybugs”. In Study 1 of Rhodes et al., 2012, children were read the 16 page book (each introducing a unique Zarpie with a unique property using language determined by the child’s condition) twice on the first day of research, twice on a second day of research (approximately 3 days later). On a third day of research (approximately 3 days later), children completed a series of test questions assessing the extent to which they held essentialist beliefs about Zarpies. Adapted from “Cultural transmission of social essentialism” by Rhodes, Leslie, & Tworek, 2012, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Copyright 2012, National Academy of Sciences. Adapted with permission.

Subsequently, in the Non-Generic conditions, children (and adults) reliably rejected essentialist beliefs about Zarpies after exposure to the book. That is, although they learned the category “Zarpie”, they did not expect Zarpie properties to be determined by birth, they did not expect individuals to do certain behaviors because they are Zarpies, and they did not expect all Zarpies to share either the properties mentioned in the book or other new properties. In contrast, the Generic condition significantly increased the likelihood of these essentialist beliefs among both preschool-age children and adults, with effects persisting for at least several days after exposure to the generic language (see Figure 2). Follow-up control studies confirmed that it was the genericity of the target sentences—not simply their syntactic plurality—that elicited these effects (e.g., indefinite singular generics, such as “A Zarpie sleeps in tall trees” had similar consequences as bare plural generics, “Zarpies sleep in tall trees”). Thus, preschool-age children appear to require stronger linguistic cues—in this case, generic language—to assume that new social categories are essentialized kinds.

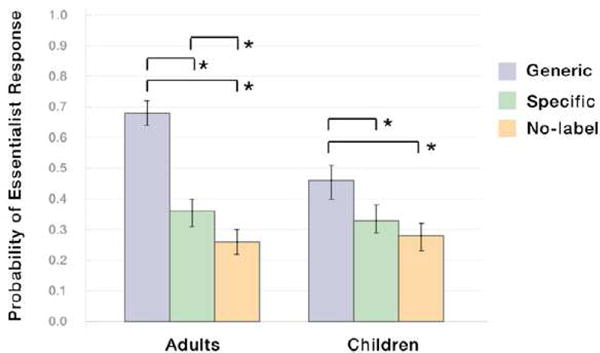

Figure 2.

Probabilities of essentialist responses by condition for Study 1 from Rhodes et al., 2012 [34]. Error bars represent Wald 95% confidence intervals. Data are from a composite measure of essentialist beliefs that included the extent to which participants expected category properties to be determined by birth or the environment, the extent to which they explained individual properties by reference to the category, and the extent to which they thought of the category as homogeneous. In the two comparison conditions (Specific, No-label), children and adults reliably rejected these essentialist beliefs about the novel category, even after fairly extensive exposure to category labels and properties. The Generic condition increased the likelihood that participants would endorse essentialist beliefs about the category. Reprinted from “Cultural transmission of social essentialism” by Rhodes, Leslie, & Tworek, 2012, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. Copyright 2012, National Academy of Sciences. Reprinted with permission.

Earlier in development as well, generic language provides important strong cues that guide the acquisition of social categories. In particular, Rhodes et al. (in press) found that two-year-old children did not learn new, arbitrary ways of classifying people if exemplars were presented with simple noun labels (or no labels at all); toddlers learned and applied new ways for classifying people only if category members were described with generic language (see Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Overview of the method from Rhodes et al., in press [24]. Two-year-old children were presented with six exemplars from a novel category that was marked by a shared perceptual feature (e.g., all six wore red or blue). The language used to introduce these exemplars varied by condition, as pictured. Children were then asked to find another category member. Reliably selecting an individual that matched the preceding exemplars with respect to the perceptual feature suggests that children have learned the new way of categorizing people. Reprinted from “The role of generic language in the early development of social categorization” by Rhodes, Leslie, Bianchi, & Chalik, in press, Child Development. Copyright 2016, Society for Research in Child Development. Reprinted with permission.

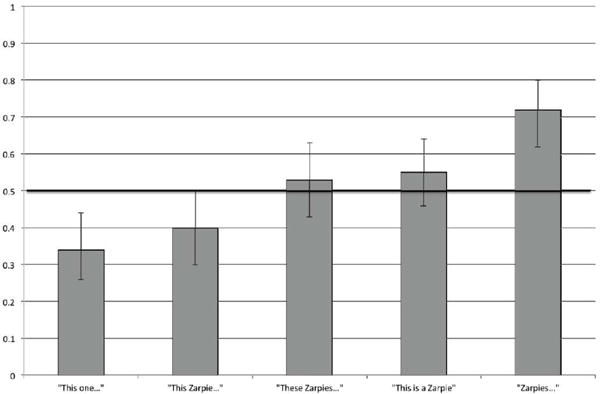

Figure 4.

Probabilities of selecting category matches for younger 2-year-olds in each of the five conditions presented across Studies 1 and 2 from Rhodes et al., in press [24]. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Two-year-olds reliably learned the new way of categorizing people only when the exemplars presented during the learning phase were introduced with generic language. Reprinted from “The role of generic language in the early development of social categorization” by Rhodes, Leslie, Bianchi, & Chalik, in press, Child Development. Copyright 2016, Society for Research in Child Development. Reprinted with permission.

It is important to note that these findings do not indicate that generic language creates or directly communicates essentialist thought, or that essentialism, in general requires exposure to generic language to develop. As described above, essentialism arises as children rely on basic representational and explanatory biases to make sense of the world around them. Within this framework, generics serve to guide to which categories children end up applying essentialist beliefs, particularly in the social realm.

Social essentialism is early emerging and widespread across cultures

Because essentialism is a product of children making sense of the world by relying on basic conceptual biases, essentialist beliefs about some types of social divisions should be widespread and early emerging, even as the targets of those beliefs show variability and change. Indeed, essentialist beliefs about social groupings have been found to arise quite early in childhood (e.g., by ages 3–5) in every cultural context studied to date (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of findings regarding age of emergence and component of essentialist beliefs tested by type of social category

| Type of Social Category | Ages tested (years) | Age of emergence (years)a | Country | Component(s) of Essentialism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Rhodes, Gelman, & Karuza, 2014 | 3–4 | 3 | United States | Natural kinds |

| Gelman, Collman, & Maccoby, 1986 | 4–7 | 4 | U.S. | Homogeneity |

| Taylor, 1996 | 4–10 | 4 | U.S. | Causal, Stability |

| Rhodes & Gelman, 2009 | 5–18 | 5 | U.S. | Natural kinds |

| Diesendruck, Goldfein-Elbaz, Rhodes, Gelman, & Neumark, 2013 | 5–10 | 5 | U.S./Israel | Natural kinds |

| Taylor, Rhodes, & Gelman, 2009 | 5–10 | 5 | U.S. | Strict boundaries, Causal, Stability |

| Race | ||||

| Hirschfeld, 1995 | 3–7 | 3 | U.S. | Stability |

| Roberts & Gelman, 2015 | 4–13 | 4* | U.S. | Natural kinds |

| Kinzler & Dautel, 2012 | 5–10 | 5* | U.S. | Stability |

| Diesendruck, Goldfein-Elbaz, Rhodes, Gelman, & Neumark, 2013 | 5–10 | 5* | U.S./Israel | Natural kinds |

| Gaither, Schultz, Pauker, Sommers, Maddox, & Ambady, 2013 | 4–9 | 6–9 | U.S. | Stability |

| Pauker, Xu, Williams, & Biddle, in press | 4–11 | 7–11* | U.S. | Stability |

| Rhodes & Gelman, 2009 | 5–18 | 10* | U.S. | Natural kinds |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Diesendruck & HaLevi, 2006 | 4–6 | 4 | Israel | Homogeneity |

| Deeb, Segall, Birnbaum, Ben-Eliyahu, & Diesendruck, 2011 | 5–11 | 5 | Israel | Homogeneity, Stability, Discreteness |

| Diesendruck, Goldfein-Elbaz, Rhodes, Gelman, & Neumark, 2013 | 5–10 | 5 | U.S./Israel | Natural kinds |

| Diesendruck, Birnbaum, Deeb, & Segall, 2013 | 5–11 | 5 | Israel | Stability |

| Birnbaum, Deeb, Segall, Ben-Eliyahu, & Diesendruck, 2010 | 5–11 | 5 | Israel | Homogeneity |

| Astuti, Solomon, & Carey, 2004 | 6–13 | 6 | Madagascar | Stability, Causal |

| Language | ||||

| Hirschfeld & Gelman, 1997 | 3–5 | 5 | U.S. | Causal, Stability |

| Kinzler & Dautel, 2012 | 5–10 | 5 | U.S. | Stability |

| Religion | ||||

| Smyth, Pendergrast, Feeney, Coley, Eidson, & Niens, 2012 | 7–11 | 7* | Ireland | Homogeneity |

| Social Class | ||||

| Diesendruck & HaLevi, 2006 | 4–6 | 4 | Israel | Homogeneity |

The ages of emergence listed are the youngest at which the cited paper provides evidence that children, as a group, showed reliable essentialist beliefs (e.g., significantly more than 50% of children showed such beliefs, or essentialist responses were given more than 50% of the time). In some cases, some proportion of younger children showed highly essentialist beliefs, as there is substantial individual variation in these developmental trajectories.

Reliable essentialist beliefs were found in only some samples of children at this age (e.g., Black or White children)

For example, by age 4, children in the United States show essentialist beliefs about gender; in particular, they expect that a baby who is born a girl, for example, will inevitably grow up to share female-typical biological and behavioral properties, even if she grows up surrounded by all males25,33. At ages 3–5, children also view gender categories as having objective boundaries that mark discrete kinds of people21,22. Also by age 4, preschool children treat gender category label as more important than observable features in predicting an individual’s behavioral and biological properties28. All of these data are consistent with the proposal that children think about gender as if a person’s gender stems from an intrinsic category essence that is obtained before birth, which causally constrains the development of individual properties and gives rise to within-category commonalities.

Although gender categories have provided the clearest evidence of social essentialism in early childhood, young children also sometimes hold essentialist beliefs about some other types of social categories as well. For example, Jewish religious children growing up in Israel view ethnic categories (e.g., Arab, Jew) in essentialist terms—they expect ethnicity and ethnically-linked properties to be determined by birth71,72, treat the boundaries of ethnic categories as objective and absolute18, and expect members of the same ethnic category to share novel properties even if they have different personalities from one another27. By age 4, young children in the United States often think that the language spoken by one’s birth parents, rather than the language in a child’s environment, determines which language a baby will grow up to speak (in contrast to adult beliefs31). Further, children growing up in western Madagascar, among a culture in which adults explicitly subscribe to anti-essentialist, performance-based views of how membership in social groups are determined, nevertheless expect that ethnic group memberships are determined by birth73.

That such beliefs arise so early in development, in the absence of much exposure to explicit talk about “essences” or things like genes or DNA (and sometimes in direct contrast to the views held by adults in the child’s community,31,73), is consistent with the view that such beliefs arise from children’s basic conceptual biases that they rely on for understanding the world, as opposed to from direct instruction (e.g., exposure to information about genes that they might obtain in a science class, as proposed by Fodor74).

Cross-cultural and developmental variability

Although essentialist beliefs about social groupings appear to be widespread, there is also important cross-cultural and developmental variability in the precise nature of these beliefs. These patterns illustrate the critical role that cultural input and experience play in shaping the development of social essentialism. For example, although young children often hold essentialist views of gender, these beliefs have been found to decline across age, in a context-dependent manner. Taylor33 and Taylor et al.25 reported that older children and adults viewed gender-stereotyped behaviors (e.g., preferring princess to toy trucks) as determined by the environment, rather than by birth (see also75,76). Participants in these samples, however, were living in a socially and politically liberal university town. Rhodes and Gelman21 compared children of various ages living in this relatively liberal town with those from a town only 75 miles to the west, but one that is considerably more socially and politically conservative, as well as more racially and ethnically homogeneous. This work revealed that essentialist beliefs about gender declined in the relatively liberal town, but did not show evidence of developmental change in the more conservative community (in this work, children ages 5, 7, 10, and 17 all treated the boundaries of gender categories as objectively determined to the same degree). While this comparative study could not isolate any particular features of these environments that accounted for the community-level differences, they illustrate the role of cultural context—rather than domain-general cognitive changes—that contribute to whether and how essentialist beliefs about gender change across development.

Further, cultural context has been found to strongly shape whether children of various ages, as well as adults, represent other social categories—beyond gender—in essentialist terms. For example, in Rhodes and Gelman21 described above, younger children (ages 5 and 7) in both of the communities did not have essentialist beliefs about race. Although children of these ages could categorize based on race, they did not view racial categories as marking objective, fundamentally distinct kinds of people. This essentialist view of race was observed only among older children (ages 10 and 17) in the more conservative, ethnically homogeneous community. Consistent with these findings, other research has found that whether children of various ages view race as stable over time—a key component of essentialist beliefs—also varies as a function of the community that children are growing up in and of their own racial-ethnic background23,32. As further evidence of cultural variability, among children growing up in Israel, essentialist beliefs about religious-ethnic categories vary by the children’s own group membership, the religiosity of their community, the composition of their school, and their parents’ political ideology71,72,77–79. Also, comparing children from Israel and the United States shows that children in the United States have more essentialist beliefs about race than children in Israel, whereas children in Israel have more essentialist beliefs about religious-ethnic categories18. Further, children growing up in Northern Ireland develop more essentialist beliefs about religious differences (Catholic vs. Protestant) than children growing up in Boston, although even in Northern Ireland, these essentialist beliefs are fairly late developing (ages 8–10) and are held more strongly by children growing up in schools that are segregated by religion29. These types of results have been found outside of Western countries and into adulthood as well. In India, adults from upper social classes view caste in essentialist terms, whereas adults from lower classes do not80.

What all of these patterns illustrate is that cultural context plays a key role in the development and expression of essentialist beliefs. We are not claiming that all of essentialism is communicated via culture. As we have described, essentialist beliefs emerge early, in the absence of direct instruction (and sometimes in contrast to the beliefs held by adults in the community). Rather, it appears that children have general conceptual biases to expect that some social groupings reflect essential kinds, and that cultural input and experience shapes how they map those beliefs onto particular categories in their environment. In some communities, children develop the belief that race marks essential kinds, in others that religion does so, in others social class, and so on. This proposal—that essentialist beliefs result from the interplay of children’s general conceptual biases and the cultural input that they receive—can explain both why essentialist beliefs are so pervasive across highly diverse cultures and persistent across historical and developmental time, but also why the categories that become the targets of these beliefs vary markedly across those same factors.

As described earlier, the language that children hear about social categories in their environment likely contributes to these patterns of cultural variation. Indeed, Segall, Birnbaum, Deeb, and Diesendruck79 found that variation in children’s essentialist beliefs about ethnicity across children drawn from religious, secular, and integrated schools was partially explained by variation in their parents use of generic language when discussing ethnic categories with their children (e.g., “Arabs don’t do this”: for similar patterns regarding gender, see81 and for further evidence of the relation between parents’ social attitudes and children’s essentialism, see21). As an experimental demonstration of these processes, Rhodes et al.34 found that inducing essentialist beliefs in parents led them to produce more generic language in conversations about a novel social category with their children. Thus, generic language may serve as a covert mechanism by which essentialist beliefs about particular categories are passed on across generations.

Yet, the patterns obtained from cross-cultural and cross-community studies also suggest a number of other correlates of variation in essentialism. For example, children from majority groups who attend purposefully integrated schools often have fewer essentialist beliefs about the relevant category, particularly in older childhood29,77. In the United States, however, it is also notable that African American children (who, on average, live in more integrated neighborhoods) appear to develop essentialist beliefs about race at a younger age than White children23,32). Thus, different processes might contribute to the development of essentialist beliefs among members of different groups. Future research should identify the more proximal mechanisms by which early experiences with diversity (or lack thereof) shape the development of essentialist beliefs.

The possibly special case of gender and probably not special case of race

To wrap up this section on how social essentialist beliefs develop, it is useful to address directly the extent to which the present proposal accounts for the development of essentialist beliefs regarding all categories, in particular, for racial and gender categories, which have been the subject of the most interest and debate. At various times in the history of the field, proposals have been put forth that there is something intrinsic to the way humans represent these categories that makes them particularly likely to elicit essentialist beliefs. For example, Gil-White37 proposed that people are predisposed to represent ethnic groups in essentialist terms; he argued that evolution selected for a tendency to represent ethnic groups like distinct biological kinds because it promoted within-group coordination and the avoidance of costly interactions with out-group members. Further, given the importance of biological sex in mate selection and reproduction, across human societies and across species, some authors have suggested that gender representations might be particularly constrained82.

To what extent are the developmental and cross-cultural data consistent with these proposals? For gender, currently available data are consistent with the possibility that concepts of gender categories are more strongly constrained by intuitive biases than other dimensions of social organization. As reviewed earlier, children show strongly essentialist beliefs about gender categories, on multiple measures of essentialism, at a quite young age, and they do so even when older children and adults in their community have more flexible views of gender categories21. This pattern is consistent with the possibility that gender concepts are more strongly shaped by initial biases, at least early in development. Further, other research on gender categories supports the conclusion that such representations are fairly constrained—manipulations that interrupt categorization on other salient social criteria (e.g., race) fail to do so for gender83, and automatic encoding of gender (but not of race) develops early84 and appears fairly consistent across development85. Further, research on gender essentialism in adults suggests that although gender essentialist beliefs are often weaker in adults than in early childhood, even adults show more strongly essentialist beliefs about gender on more implicit measures or when they are under cognitive load86. A number of authors have proposed that due to the importance of biological sex across species, there are evolved biases specifically to classify by sex. One possibility is thus that children are likely to develop essentialist beliefs about gender based on a categorical distinction that they are evolutionarily predisposed to find particularly salient. Nevertheless, none of the reported data provide conclusive evidence that essentialist beliefs about gender are more highly constrained than for other categories. Other environmental features that make such categories salient87, including abundant exposure to generic language that references gender categories early in childhood81, could also explain the relatively early development of such beliefs.

Another category that has been proposed as particularly likely to elicit essentialist beliefs are those based on ethnicity or race37. As initial support for these proposals, Hirschfeld88 presented a series of studies that were interpreted as indicating that essentialist conceptions of race emerge quite early in development. Hirschfeld88 showed that by age four, children would predict that a baby born to white parents but raised by black parents (or vice versa) would grow up to have the skin color of their birth parents, which was interpreted as evidence that children view race as determined by an intrinsic causal essence.

Follow-up work using a similar method, however, found that while children of this age do appear to treat skin color as inherited as documented by Hirschfeld88, they do not necessarily view skin color as a marker of an important category membership. Instead, they appear to reason about skin color just like they reason about many other physical properties. By age 4, children also expect babies to have the hair color, eye color, and novel internal biological properties of their birth parents in similar paradigms89. Thus, while Hirschfeld showed that children view certain observable physical properties as inherited instead of determined by the environment of upbringing (a reasonable developmental precursor to an essentialist conception of race), these data do not provide evidence that children view racial categories in essentialist terms.

Indeed, given that systems of racial and ethnic classification show vast cultural and historical variability, that comparable groupings are not common across species, and that such groupings may not have been relevant or meaningful throughout the course of human evolution, many have challenged the claim that children are particularly predisposed to develop essentialist beliefs about race or ethnicity (e.g.,32,83,90,91). Consistent with this perspective, subsequent research has found that essentialist beliefs about race follow a protracted time course, and show substantial variability across communities and based on children’s own background. As described earlier, Rhodes and Gelman21 found that the belief that race marks objectively distinct kinds of people did not develop until ages 7–10, and only did so more in relatively homogeneous and socially and politically conservative communities (see also22). Similarly, Kinzler and Dautel32 found that white children did not view skin color as stable over time (see also92,93) at ages 5–6, whereas black American children did so at these ages (see also23). Thus, there is to date no empirical evidence that essentialist beliefs about race emerge early in development or that children are more strongly predisposed to view race in these terms than any other type of social category. Rather, the development of essentialist conceptions of race appears more dependent on the interplay of basic conceptual biases toward essentialism with rather protracted cultural experiences.

THE DEVELOPMENTAL CONSEQUENCES OF ESSENTIALIST BELIEFS

We turn now to the social and behavioral processes that follow from the development of essentialist beliefs about the social world. In influential work on the psychological foundations of prejudice Gordon Allport94 wrote that prejudice arises once, “…a belief in essence develops. There is an inherent ‘Jewishness’ in every Jew. The ‘soul of the Oriental,’ ‘Negro blood,’… ‘the passionate Latin’—all represent a belief in essence. A mysterious mana (for good or ill) resides in a group, all of its members partaking thereof.” With this quote, Allport describes the intuition that an essentialist view of social groupings underlies some of the most pernicious problems of inter-group relations.

Empirical work over the last several decades has examined the implications of essentialism for stereotyping, prejudice, and other aspects of inter-group behavior, focusing predominantly on adult samples. Indeed essentialist beliefs about race, gender, ethnicity, and religion have been found to correlate with increased stereotyping and more negative out-group attitudes in adult populations16,95–100. Experimental research has also confirmed that essentialist beliefs contribute to negative inter-group phenomena in adult populations12,13,101,102. For example, Williams and Eberhardt13 found that adults who were exposed to information attributing racial differences to biological, instead of social, determinants exhibited greater prejudice toward minority, out-group members.

Yet, considerably less research has examined the social and behavioral implications of essentialist beliefs in early childhood. This issue has important theoretical stakes for understanding the mechanisms by which essentialism contributes to inter-group phenomena, as well as for understanding the development of inter-group relations more generally. From correlational and experimental research on adults, it is impossible to tell if essentialism uniquely contributes to the formation of negative inter-group phenomena, or only relates to negative inter-group attitudes once it intersects with other aspects of experience, beliefs, knowledge, and so on. If essentialism is necessary and sufficient for the development of negative attitudes toward out-group members, then the development of essentialist beliefs in early childhood should have immediate negative consequences for inter-group attitudes and behavior, even before children have much experience with the relevant group distinctions or specific knowledge of societal stereotypes and attitudes toward specific groups (e.g., boys versus girls, Blacks versus Whites, homosexuals versus heterosexuals). However, if essentialism contributes to but is not in itself sufficient for the development of negative inter-group attitudes, then the relation between essentialism and negative inter-group phenomena might emerge later in development. Relevant developmental research on the relation of essentialism to three components of inter-group relations: stereotyping, inter-group interactions, and social prejudice, lays the groundwork to explore these hypotheses.

Stereotyping

The proposed mechanism linking essentialism to stereotyping is relatively straightforward—essentialism entails expectations of within-category homogeneity, thus stronger essentialist beliefs seem likely to lead to greater willingness to assume that category members will all share the same traits. Indeed, stronger essentialist beliefs have been related to increased out-group stereotyping in young children93,103,104. For example, Pauker et al.104 found among children ages 3–10 that essentialist beliefs about race predicted children’s endorsement of negative racial stereotypes (see also103; for similar findings in adults, see15,105–108).

Inter-group Interaction

Another mechanism by which essentialism has been proposed to influence inter-group relations is via the intensification of category boundaries. Part of essentialism entails viewing category boundaries as objective, discrete, and inflexible. In adults, this component of essentialism has been found to decrease the likelihood that people will choose to interact with members of other groups13,100,103,109,110. Further this component of essentialism leads people to overlook, ignore, or exclude from their representations individuals who exist around the boundaries of categories111–114. This occurs in children as well; for example, Gaither et al.93 found that children with more essentialist beliefs about race had worse memory for racially ambiguous faces than children who had not developed such beliefs.

Further, Rhodes et al.24 found that experimentally inducing essentialist beliefs in young children (using similar methods as in Figures 1–2), led children to share fewer resources with members of essentialized out-group members. In this work, the extent to which children perceived the relevant category boundaries as absolute and discrete predicted the extent to which they withheld resources from out-group members. These findings suggest that boundary intensification can reduce children’s willingness to engage pro-socially with members of other groups.

Prejudice

In addition to leading to stereotyping and boundary intensification (and related perceptual, conceptual, and behavioral phenomena), Allport94 and others have hypothesized that essentialism also contributes to the more affective processes that comprise social prejudice (i.e., feelings of out-group dislike). Indeed, in adult populations, essentialist beliefs about race, for example, are associated with more racial prejudice, and experimental research has confirmed that increasing essentialist beliefs leads to corresponding increases in such prejudiced attitudes12,13. Similarly, in children, Diesendruck and Menahem115 found that increasing the salience of four-year-old Israeli children’s essentialist beliefs about ethnicity led them to draw members of different groups farther apart (indicating perhaps that they perceived more social distance between groups) and to draw in-group members with more positive affect than out-group members, suggesting that essentialism leads children to feel more negatively toward out-group members.

Broadly, there are at least two types of mechanism that could underlie such effects, with somewhat different developmental and social consequences. One possibility is that because essentialism implies more within-category homogeneity and between-category differences, essentialism increases in-group identification and makes people feel that out-group members are more highly dissimilar from themselves. If so, then essentialism might contribute to prejudice by emphasizing out-group difference—in its most extreme form, perhaps even leading people to dehumanize out-groups (as essentialism implies that members of different categories reflect fundamentally distinct kinds; e.g.,110,116,117). On this account, essentialist beliefs about social out-groups would lead directly to social prejudice.

Alternately—or additionally—however, essentialism could lead to social prejudice by leading people to view the social world as reflecting objective structure (e.g.,118). On this account, because essentialism leads people to view category boundaries and category-based differences as natural and objectively-accurate reflections of an underlying reality, essentialism leads people to confront category-linked differences in their environment—including differences in status—as reflecting objective structure in the world. From this account, essentialism could contribute to the belief that low status groups are somehow inherently low status, and thus lead people to devalue members of those groups. From this perspective, essentialism leads to social prejudice because it legitimizes the devaluing of low status groups. Thus, essentialism would lead to prejudice particularly toward low status groups (not all social out-groups). Further, across development, essentialism would only lead to prejudice once children began to use relevant social group memberships as cues to status differences.

While essentialism does appear to increase in-group identification, at least in adult participants (e.g.,80,119,120), there is also evidence from multiple lines of work supporting this second account of how essentialism negatively influences inter-group relations (e.g.,12,101,102). For example, Mandalaywala et al.121 found that racial essentialism related (both correlationally and experimentally) to more negative attitudes toward blacks in both black and white adults, and that these effects were mediated by increases in system-justifying beliefs. Thus, essentialism led to more negative attitudes toward members of a low-status group because it led people to treat status differences as reflecting natural structure, and it did so regardless of whether participants were themselves members of that group. This pattern is consistent with the possibility that essentialism leads to prejudice by increasing endorsement of the status quo, not (only) by increasing in-group identification or perceptions of out-group difference.

Further, although Rhodes et al.122 found that inducing essentialism toward a novel out-group led children to withhold more resources from out-group members (as described earlier), there was no evidence in these studies that essentialism led children to dislike or feel more negatively toward out-group members. For example, essentialism did not influence whether children said they liked out-group members, whether they wanted to invite them to their birthday parties, or how closely they chose to sit to an out-group member. The essentialism manipulation influenced only resource sharing—a process that has been described as depending more on calculations of expected reciprocity than on positive or negative feelings toward potential targets123,124. In this work, children had no information about social status; thus, these findings are consistent with the possibility that essentialism might lead to prejudice only once it interacts with information about status differences between groups.

CONCLUSION

As discussed above, essentialism is not a unitary construct, but rather is comprised of a variety of components (Table 1) that exhibit various degrees of relatedness. Studies in adults sometimes separate these components, examining each component’s effects on inter-group stereotypes, relations, and attitudes separately (e.g.,11,16,125); but developmental research on social essentialism would benefit greatly from moving beyond a unitary concept of essentialism to describe and compare the developmental trajectory of each component. In addition to enhancing our understanding of how each aspect of essentialism arises (e.g., what conceptual biases or cultural input gives rise to each component?), such research will also inform our understanding of essentialism’s relationships to inter-group attitudes and beliefs.

This is crucial because essentialism exhibits a complex relationship to inter-group relations. Although essentialism often relates to negative attitudes toward lower-status groups, some components of essentialism can also relate to increased in-group identification, which can have positive consequences for members of low-status minority groups12. Thus, it is critical to examine how each component of essentialism develops in early childhood, and to carefully track the implications of each for members of both high and low status groups. To properly study these questions, it is essential to study a diverse group of children, especially incorporating minority children into research30. By incorporating children for whom the in-group and the socially preferred group are traditionally the same (e.g., majority race or male children) as well as children for whom the in-group and the socially preferred group often differ (e.g., minority race or female children), studies will be able to develop a comprehensive framework of how social essentialist beliefs develop and of the developmental consequences of these beliefs for children from diverse backgrounds.

Caption.

Essentialist views of the social world are widespread and early developing, with key implications for inter-group relations.

References

- 1.Gelman SA. Psychological essentialism in children. Trends Cogn Sci. 2004;8:404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medin DL, Ortony A. Similarity and Analogical Reasoning. 1989:179–195. doi: 10.1017/cbo9780511529863.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gelman SA. The essential child: Origins of essentialism in everyday thought. 2003 doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195154061.001.0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leslie SJ. Essence and natural kinds?: When science meets preschooler. Oxford Stud Epistemol. 2013;4:108–165. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayr E. The growth of biological thought: Diversity, evolution, and inheritance. Harvard University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayr E. Toward a new philosophy of biology: Observations of an evolutionist. Harvard University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewontin R. The apportionment of human diversity. Evolutionary Biology. 1972;6:381–398. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nei M, Roychoudhury AK. Genetic relationship and evolution of human races. Evol Biol. 1982;14:1–59. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyde JS. The gender similarities hypothesis. Am Psychol. 2005;60:581–592. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirschfeld LA. Race in the making: Cognition, culture, and the child’s construction of human kinds. MIT Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haslam N, Rothschild L, Ernst D. Essentialist beliefs about social categories. Br J Soc Psychol. 2000;39:113–127. doi: 10.1348/014466600164363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandalaywala TM, Rhodes M, Amodio DM. Essentialism leads to racial prejudice by increasing acceptance of the status quo. under Rev. doi: 10.1177/1948550617707020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams MJ, Eberhardt JL. Biological conceptions of race and the motivation to cross racial boundaries. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;94:1033–1047. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.6.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelman SA, Coley JD. In: Perspectives on language and thought: Interrelations in development. Byrnes JP, Gelman SA, editors. Cambridge University Press; 1991. pp. 146–196. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prentice DA, Miller DT. Psychological essentialism of human categories. 2007;16:202–206. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vincent Y, Olivier C, Claudia E. The interplay of subjective essentialism and entitativity in the formation of stereotypes. Personal Soc Psychol Rev. 2001;5:141–155. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelman SA, Heyman GD, Legare CH. Developmental changes in the coherence of essentialist beliefs about psychological characteristics. 2007;78:757–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diesendruck G, Goldfein-Elbaz R, Rhodes M, Gelman SA, Neumark N. Cross-cultural differences in children’s beliefs about the objectivity of social categories. Child Dev. 2013;84:1906–1917. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gelman SA, Kalish CW. In: Emerging themes in cognitive development. Pasnak R, Howe ML, editors. Springer-Verlag; 1993. pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalish CW. Natural and artifactual kinds: are children realists or relativists about categories? Dev Psychol. 1998;34:376–391. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhodes M, Gelman SA. A developmental examination of the conceptual structure of animal, artifact, and human social categories across two cultural contexts. Cogn Psychol. 2009;59:244–274. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rhodes M, Gelman SA, Karuza JC. Preschool Ontology: The Role of Beliefs about Category Boundaries in Early Categorization. J Cogn Dev. 2014;15:120917081755004. doi: 10.1080/15248372.2012.713875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roberts SO, Gelman SA. Do Children See in Black and White? Children’s and Adults’ Categorizations of Multiracial Individuals. Child Dev. 2015;86:1830–1847. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhodes M, Leslie SJ, Bianchi L, Chalik LT. The role of generic language in the early development of social categorization. Press. :1–18. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor MG, Rhodes M, Gelman SA. Boys will be boys; Cows will be cows: Children’s essentialist reasoning about gender categories and animal species. Child Dev. 2009;80:461–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rhodes M, Gelman SA. Five-year-olds’ beliefs about the discreteness of category boundaries for animals and artifacts. Psychon Bull Rev. 2009;16:920–924. doi: 10.3758/PBR.16.5.920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diesendruck G, HaLevi H. The role of language, appearance, and culture in children’s social category-based induction. Child Dev. 2006;77:539–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gelman SA, Collman P, Maccoby EE. Inferring properties from categories versus inferring categories from properties: The case of gender. Child Dev. 1986;57:396–404. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smyth K, et al. The Inductive Potential of Religion Categories in Northern Ireland. Proc 34th Annu Conf Cogn Sci Soc. 2012:2351–2356. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waxman SR. Social categories are shaped by social experience. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012;16:531–532. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirschfeld LA, Gelman SA. What young children think about the relationship between language variation and social difference. Cogn Dev. 1997;12:213–238. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kinzler KD, Dautel JB. Children’s essentialist reasoning about language and race. Dev Sci. 2012;15:131–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor MG. The development of children’s beliefs about social and biological aspects of gender differences. Child Dev. 1996;67:1555–1571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rhodes M, Leslie SJ, Tworek CM. Cultural transmission of social essentialism. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:13526–13531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208951109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cimpian A, Markman EM. The generic/nongeneric distinction influences how children interpret new information about social others. Child Dev. 2011;82:471–492. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atran S. Folk biology and the anthropology of science: cognitive universals and cultural particulars. Behav Brain Sci. 1998;21:547–609. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x98001277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gil-White F. Are ethnic groups biological species to the human brain? Curr Anthropol. 2001;42:515–554. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pinker S. The language instinct: How the mind creates language. Harper Perennial Modern Classics; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saxe R, Tenenbaum JB, Carey S. Secret agents: Inferences about hidden causes by 10- and 12-month-old infants. Psychol Sci. 2005;16:995–1001. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dewar KM, Xu F. Induction, overhypothesis, and the origin of abstract knowledge: Evidence from 9-month-old infants. Psychol Sci. 2010;21:1871–1877. doi: 10.1177/0956797610388810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xu F. Sortal concepts, object individuation, and language. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gopnik A, Astington JW. Children’s understanding of representational change and its relation to the understanding of false belief and the appearance-reality distinction. Child Dev. 1988;59:26–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jaswal VK. Believing what you’re told: Young children’s trust in unexpected testimony about the physical world. Cogn Psychol. 2010;63:248–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cimpian A, Salomon E. The inherence heuristic: An intuitive means of making sense of the world, and a potential precursor to psychological essentialism. Behav Brain Sci. 2014;37:461–480. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X13002197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodman N. Fact, Fiction, Forecast. Harvard University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shipley E. In: Psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in Research and Theory. Medin D, editor. Academic Press Inc; 1993. pp. 265–298. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jaswal VK, Markman EM. Looks aren’t everything: 24-month-olds’ willingness to accept unexpected labels. J Cogn Dev. 2007;8:93–111. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Putnam H. The meaning of ‘meaning’. Minnesota Stud Philos Sci. 1975;7:131–193. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quine PC. In: Naming, necessity, and natural kinds. Schwart & Z, S. P., editor. Cornell University Press; 1977. pp. 155–176. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwartz SP. Natural kind terms. Cognition. 1979;7:301–315. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wilson RA. Species: New interdisciplinary essays. MIT Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Atran S, Estin P, Coley JD, Medin DL. Generic species and basic levels: Essence and appearance in folk biology. J Ethnobiol. 1997;17:17–43. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lopez A, Atran S, Coley JD, Medin DL, Smith EE. The tree of life: Universal and cultural features of folkbiological taxonomies and inductions. Cogn Psychol. 1997;32:251–295. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Medin DL, Atran S. Folkbiology. MIT Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gelman SA, Koenig MA. In: Early category and concept development: Making sense of blooming, buzzing confusion. Rakison DH, Oakes LM, editors. Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 330–359. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gopnik A, Wellman H. Reconstructing constructivism: Causal models, Bayesian learning mechanisms, and the theory theory. Psychol Bull. 2012;138:1085–1108. doi: 10.1037/a0028044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wellman HM, Gelman SA. Cognitive development: Foundational theories of core domains. Annu Rev Psychol. 1992;43:337–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.43.020192.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brandone AC, Gelman SA. Differences in preschoolers’ and adults’ use of generics about novel animals and artifacts: A window onto a conceptual divide. Cognition. 2009;110:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Diesendruck G. Categories for names or names for categories? The interplay between domain-specific conceptual structure and language. Lang Cogn Process. 2003;18:759–787. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dunham Y, Baron AS, Carey S. Consequences of ‘minimal’ group affiliations in children. Child Dev. 2011;82:793–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01577.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kalish C. Generalizing norms and preferences within social categories and individuals. Dev Psychol. 2012;48:1133–1143. doi: 10.1037/a0026344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kalish C, Lawson C. Development of social category representations: Early appreciation of roles and deontic relations. Child Dev. 2008;79:577–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rhodes M, Brickman D. The influence of competition on children’s social categories. J Cogn Dev. 2011;12:194–221. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rhodes M, Naïve theories of social groups Child Dev. 83:1900–1916. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rhodes M, Chalik L. Social categories as markers of intrinsic interpersonal obligations. Psychol Sci. 2013;24:999–1006. doi: 10.1177/0956797612466267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carlson G, Pelletier FJ. The Generic Book. The University of Chicago Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leslie SJ. Generics: Cognition and acquisition. Philos Rev. 2008;117:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cimpian A, Brandone AC, Gelman SA. Generic statements require little evidence for acceptance but have powerful implications. Cogn Sci. 2010;34:1452–1482. doi: 10.1111/j.1551-6709.2010.01126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gelman SA, Heyman GD. Carrot-Eaters and Creature Believers: The Effects of Lexicalization on Children’s Inferences About Social Categories. Psychol Sci. 1999;10:489–493. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gelman SA, Ware EA, Kleinberg F. Effects of generic language on category content and structure. Cogn Psychol. 2010;61:273–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Birnbaum D, Deeb I, Segall G, Ben-Eliyahu A, Diesendruck G. The development of social essentialism: The case of Israeli children’s inferences about Jews and Arabs. Child Dev. 2010;81:757–777. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Diesendruck G, Haber L. God’s categories: The effect of religiosity on children’s teleological and essentialist beliefs about categories. Cognition. 2009;110:100–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Astuti R, Solomon GEA, Carey S. Constraints on conceptual development. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2004;69:vii–135. doi: 10.1111/j.0037-976X.2004.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fodor JA. Concepts: Where cognitive science went wrong. (Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Berndt TJ, Heller KA. Gender stereotypes and social inferences: A developmental study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;50:889–898. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Biernat M. Gender stereotypes and the relationship between masculinity and femininity: a developmental analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61:351–365. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Deeb I, Segall G, Birnbaum D, Ben-Eliyahu A, Diesendruck G. Seeing isn’t believing: The effect of intergroup exposure on children’s essentialist beliefs about ethnic categories. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2011;101:1139–1156. doi: 10.1037/a0026107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Diesendruck G, Birnbaum D, Deeb I, Segall G. Learning what is essential: Relative and absolute changes in children’s beliefs about the heritability of ethnicity. J Cogn Dev. 2013;14:546–560. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Segall G, Birnbaum D, Deeb I, Diesendruck G. The intergenerational transmission of ethnic essentialism: how parents talk counts the most. Dev Sci. 2015;18:543–555. doi: 10.1111/desc.12235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mahalingam R. Essentialism, Culture, and Power: Representations of Social Class. J Soc Issues. 2003;59:733–749. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gelman SA, Taylor MG, Nguyen SP, Leaper C, Bigler RS. Mother-child conversations about gender: Understanding the acquisition of essentialist beliefs. Child Dev. 2004;69 [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kenrick D. Evolutionary Social Psychology: From Sexual Selection to Social Cognition. Adv Exp Soc Psychol. 1994;26:75–121. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kurzban R, Tooby J, Cosmides L. Can race be erased? Coalitional computation and social categorization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15387–15392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251541498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weisman K, Johnson MV, Shutts K. Young children’s automatic encoding of social categories. Dev Sci. 2015;18:1036–1043. doi: 10.1111/desc.12269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bennett M, Sani F, Hopkins N, Agostini L, Malucchi L. Children’s gender categorization: An investigation of automatic processing. Br J Dev Psychol. 2000;18:97–102. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Eidson RC, Coley JD. Not so fast: Reassessing gender essentialism in young adults. J Cogn Dev. 2014;15:382–392. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bigler RS, Liben LS. Developmental Intergroup Theory. Psychol Sci. 2007;16:162–166. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hirschfeld LA. Do children have a theory of race? Cognition. 1995;54:209–252. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(95)91425-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]