Abstract

Quantitative Structure Activity Relationship (QSAR) is the most frequently used modeling approach to explore the dependency of biological, toxicological, or other types of activities/properties of chemicals on their molecular features. In the past two decades, QSAR modeling has been used extensively in drug discovery process. However, the predictive models resulted from QSAR studies have limited use for chemical risk assessment, especially for animal and human toxicity evaluations, due to the low predictivity of new compounds. To develop enhanced toxicity models with independently validated external prediction power, novel modeling protocols were pursued by computational toxicologists based on rapidly increasing toxicity testing data in recent years. This chapter reviews the recent effort in our laboratory to incorporate the biological testing results as descriptors in the toxicity modeling process. This effort extended the concept of QSAR to Quantitative Structure In vitro-In vivo Relationship (QSIIR). The QSIIR study examples provided in this chapter indicate that the QSIIR models that based on the hybrid (biological and chemical) descriptors are indeed superior to the conventional QSAR models that only based on chemical descriptors for several animal toxicity endpoints. We believe that the applications introduced in this review will be of interest and value to researchers working in the field of computational drug discovery and environmental chemical risk assessment.

Keywords: QSAR, QSIIR, computational toxicology, HTS, predictive model, compounds, chemical descriptors, biological descriptors

1. Introduction

Many compounds entering clinical studies do not survive as a good pharmacological lead to a drug on the market. The chemical toxicology and safety has been regarded as the major reason for attrition of new drugs in the past decades 1. However, evaluation of chemical toxicity and safety in vivo at the early stage of drug discovery process is expensive and time consuming. To find the alternatives for the traditional animal toxicity testing and to understand the relevant toxicological mechanisms, many in vitro toxicity screens and computational toxicity models have been developed and implemented by academic institutes and pharmaceutical companies 2–9. In the past fifteen years, innovative technologies that enable rapid synthesis and high throughput screening of large libraries of compounds have been adopted in toxicity studies. As a result, there has been a huge increase in the number of compounds and the associated testing data in different in vitro screens. With this data, it becomes feasible to reveal the relationship between the high throughput in vitro toxicity testing results and the low throughput in vivo toxicity evaluation for the same set of compounds. Understanding these relationships could help us delineate the mechanisms underlying animal toxicity of chemicals as well as potentially improve our ability to predict chemical toxicity using short term bioassays.

The unique advantage of using a computational toxicity model in risk analysis is that a chemical could be evaluated for toxicity potentials even before being synthesized. The computational toxicity tools based on QSAR models have been used to assist in predictive toxicological profiling of pharmaceutical substances for understanding drug safety liabilities 7,10,11,12, supporting regulatory decision making on chemical safety and risk of toxicity13, and are effectively enhancing an already rigorous U.S. regulatory safety review of pharmaceutical substances14. Although the predictive QSAR modeling of toxicity are starting being used to evaluate the toxicity potential for the pharmaceutical companies and environmental agencies 10,15, most of previous studies showed that current available QSAR models did not work well to evaluate in vivo toxicity potentials, especially for new compounds not existing in the training data16,17. Due to this reason, it is needed to establish novel modeling techniques that could improve the conventional QSAR approaches to take advantage of the numerous of in vitro toxicity screening (especially the HTS) results to develop enhanced toxicity models.

2. Availability of large compound collections for in vivo and in vitro toxicity evaluation

Since 1990s, great efforts of developing toxicity testing methods have generated an extensive amount of toxicity data 18. However, most of the available toxicity databases that house these data are not suitable for developing QSAR toxicity models. All the cheminformatics tools require the biological data to be associated with molecular structures, and these are not included in many existing databases. Furthermore, the testing data may be not easily accessed by modelers or the quality is questionable 18. In the end, the existing errors of chemical structures also greatly affect the reliability and predictivity of the predictive models based on these databases19,20. As the result, the ‘lack of data’ problem is always the first issue that needs to be solved in predictive toxicology field.

Much progress has been made since several toxicity data collection and/or sharing projects that were initiated in the past five years. These efforts resulted in many toxicity databases available publically or commercially 5,21–24 and most of these databases could be used to develop QSAR toxicity models. Listing a full version of available toxicity databases is outside the scope of this review. Tables 1 and 2 showed several examples of the major known publically available toxicity data sources in vivo and in vitro respectively 25–31. There are tens of thousands diverse compounds being tested in various toxicity protocols and included in these databases. To study and compare the results of same compounds obtained from different testing protocols, it is important to “read across” different toxicity databases for the target compounds and the current database landscape is still disparate and fragmented for this purpose. To address this important issue, the most recent progress of toxicity data generation is highlighted by some toxicology collaborative programs, such as Tox2132, among universities, institutes and government agencies.

Table 1.

Publicly available databases of in vivo toxicity endpoints.

|

ToxRefDB US EPA National Center for Computational Toxicology25,26 |

Toxicological Reference Database (ToxRefDB) is capturing toxicological endpoints, critical effects and relevant dose-response data from EPA’s Office of Pesticide Programs into a relational database using a standardized data field structure and vocabulary. Chemicals included in the database represent over 800 conventional pesticide active ingredients. Data types include: subchronic toxicity endpoints (rodents and non-rodents), prenatal developmental toxicity (rat and rabbit), reproductive and fertility effects (2-generation studies), immunotoxicity, developmental neurotoxicity, chronic toxicity (rat, mouse, dog) and 2-year carcinogenicity bioassays (rat and mouse). |

| DSSTox Dataset21 | Tumor target site incidence and TD50 potencies for 1354 chemical substances tested in rats and mouse, 80 chemical substances tested in hamsters, 5 chemicals tested in dogs, and 27 chemical substances tested in non-human primates; data reviewed and compiled from literature and NTP studies. |

| NIEHS/NTP Datasets27 | Data from more than 500 2-year, two species, toxicology and carcinogenesis studies collected by the NTP. The database also contains the results collected on approximately 300 toxicity studies from shorter duration tests and from genetic toxicity studies. In addition, test data from the immunotoxicity, developmental toxicity and reproductive toxicity studies are continually being added to this database. Some of the endpoint observations are labels (tox or non-tox, increased or decreased). Classification methods will be applicable to this type of studies. While others are quantitative data, e.g. TD50, these will be studied using regression type of methods. Both can be addressed by the Combi-QSPR framework, which includes multiple machine learning and statistical methods, quantitative regression as well as classification. |

| FDA adverse liver effects database28 | The database contains the following fields: generic name of each chemical, SMILES code, for module A10 (liver enzyme composite module): overall activity category for each compound (A for active, M for marginally active, or I for inactive) based on the number of active and marginally active scores for each compound at the five individual endpoints; number of endpoints at which each compound is marginally active (M); number of endpoints at which each compound is active (A); for modules A11 to A15 (alkaline phosphatase increased, SGOT increased, SGPT increased, LDH increased, and GGT increased, respectively): overall activity category for each compound (A for active, M for marginally active, or I for inactive) based on the RI and ADR values; number of ADR reports for each compound, given as <4 or =4. |

Table 2.

Public databases of in vitro toxicity endpoints.

|

NCGC qHTS cytotoxicity data2

available through PUBCHEM24 (via PubChem AID#) |

Concentration-response profiles of 1,408 substances screened for their effects on cell viability are available through PubChem for 13 cell lines: HepG2 (human hepatoma; AID #433), H-4-II-E (rat hepatoma; AID #543), BJ (human foreskin fibroblast; AID #421), Jurkat (clone E6-1, human acute T cell leukemia; AID #426), HEK293 (transformed human embryonic kidney cell; AID #427), MRC-5 (human lung fibroblast; AID #434), SK-N-SH (human neuroblastoma; AID #435), N2a (mouse neuroblastoma; AID #540), NIH 3T3 (mouse embryonic fibroblast; AID #541), HUV-EC-C (human vascular endothelial cell; AID #542), SH-SY-5Y (human neuroblastoma, subclone of SK-N-SH; AID #544), Renal Proximal Tubule (rat kidney cell; AID #545) and Mesenchymal (human renal glomeruli cell; AID #546). Each compound was tested at 14 concentrations ranging from 0.006 to 92μM and the response was measured as % change in cell viability as compared to vehicle control at each concentration. |

|

ChEMBLdb29

available through PUBCHEM24 (via PubChem AID#) |

A database of bioactive drug-like small molecules abstracted and curated from the primary scientific literature. Bioactivities are represented by binding constants, pharmacology and ADMET data. ChEMBL assays are available through PubChem. Human toxicity related endpoints are primarily from in vitro data, such as: cytotoxicity on SNU-354 cells (hepatoma cell line, AID #200819), antiproliferative action on L02 cells (normal hepatocytes, AID #416061), growth inhibition of SK-Hep1 cells (liver adenocarcinoma cell line, AID #201649), cytotoxicity and anticancer activity on HepG2 cells (AID #86696, 340104, 421266) etc. |

| ToxCastTM30 | Phase I (August 7 2009 update) provided 304 unique compounds characterized in over 600 HTS endpoints. The endpoints include biochemical assays of protein function, cell-based transcriptional reporter and gene expression, cell line and primary cell functional, and developmental endpoints in zebrafish embryos and embryonic stem cells. Additionally, mapping of these assays to 315 genes and 438 pathways was made publicly available. Phase II will complete screens of additional 700 compounds, HTS data on nearly 10,000 chemicals will be available through Tox21 collaboration in 2010. |

| ToxNET31 | A data network covering toxicology, hazardous chemicals, environmental health and related areas. Managed by US National Library of Medicine. |

3. QSAR and current challenge of computational toxicology

Computational toxicology modeling relies on the use of QSAR approaches to build the toxicity models for available reference data. It traditionally derives the computed properties solely based on the molecular structures as defined by descriptors or fingerprints and has been broadly used to predict the side effects that chemicals posed to human health or animals. The QSTR models developed from computational toxicity studies strongly depend on the QSAR approaches used in the modeling process. The optimization of the variable selected or the weighting of variables is the core component of a QSAR approach. This procedure selects only the most meaningful and statistically significant subset of available chemical descriptors in terms of correlation with biological activity. The optimum selection is achieved by combining stochastic search methods such as generalized simulated annealing 33, genetic algorithms 34 or evolutionary algorithms 35 with the correlation techniques such as MLR, PLS analysis, or artificial neural networks 33–36.

Recent research has emphasized model validation as the key component of QSAR modeling 37. We 37,38 and others 39–42 have demonstrated that various commonly accepted statistical characteristics of QSAR models derived for a training set are insufficient to establish and estimate the predictive power of QSTR models. The only way to ensure the high predictive power of a QSAR model is to demonstrate a significant correlation between predicted and observed activities of compounds for a validation (test) set, which was not employed in model development. This goal can be achieved by a division of an experimental SAR dataset into the training and test set, which are used for model development and validation, respectively. We believe that special approaches should be used to select a training set to ensure the highest significance and predictive power of QSAR models 43,44. Our recent reviews and publications describe several algorithms that can be employed for such division 37,38,44.

Most of previous QSAR studies showed that current available QSTR models do not work well to evaluate in vivo toxicity potentials, especially for external compounds. Due to this reason, several reviews were published recently to challenge the feasibility and reliability of using QSAR approaches in toxicity studies 45,46. Often, disappointing results could be linked to the key aspects of the modeling procedure, many of which related to the original data and their interpretation. Similarly, Lombardo et al. 47 noted that not much progress has been made in developing robust and predictive models, and that the lack of accurate data, together with the use of questionable modeling end-points, has hindered the real progress. Most chemical toxicity models (predictors) are either reported in the literature but not available to research community or available in the form of commercial software that is not universally successful as discussed above. These examples illustrate that although individual successes have been indeed reported as discussed above, in general there remains a strong need in developing widely accessible and reliable computational toxicology modeling techniques and specific end-point predictors.

4. Quantitative Structure In vitro In vivo Relationship (QSIIR)

To stress a broad appeal of the conventional QSAR approach, it should be made clear that from the statistical viewpoint QSAR modeling is a special case of general statistical data mining and data modeling where the data is formatted to represent objects described by multiple descriptors and the robust correlation between descriptors and a target property (e.g., chemical toxicity in vivo) is sought. In previous computational toxicology studies, additional physico-chemical properties, such as water partition coefficient (logP)48, water solubility49, and melting point50 were used successfully to augment computed chemical descriptors and improve the predictive power of QSAR models. These studies suggest that using experimental results as descriptors in QSAR modeling could prove beneficial. The current available and still rapidly growing High Throughput Screening (HTS) data for large and diverse chemical libraries makes it possible to extend the scope of the conventional QSAR in toxicity studies by using in vitro testing results as extra biological descriptors. Therefore, in some of the most recent toxicology studies, the relationships between various in vitro and in vivo toxicity testing results were generated 51–54. Based on these reports, we proposed a new modeling workflow called Quantitative Structure In vitro-In vivo Relationship (QSIIR) and used it in animal toxicity modeling studies 55–57. The target properties of QSIIR modeling were still biological activities, such as different animal toxicity endpoints, but the content and interpretation of “descriptors” and the resulting models will vary. This focus on the prediction of the same target property from different (chemical, biological and genomic) characteristics of environmental agents affords an opportunity to most fully explore the source-to-outcome continuum of the modern experimental toxicology using cheminformatics approaches.

5. Case studies

5.1. Using “hybrid” descriptors for QSIIR modeling of rodent carcinogenicity

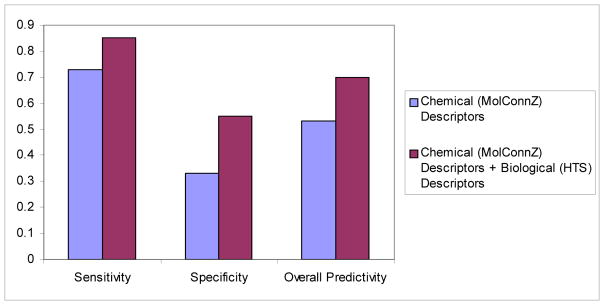

To explore efficient approaches for rapid evaluation of chemical toxicity and human health risk of environmental compounds, NTP in collaboration with the National Center for Chemical Genomics (NCGC) has initiated an HTS Project2,58. The first batch of HTS results for a set of 1,408 compounds tested in 6 human cell lines was released via PubChem. We have explored this data in terms of their utility for predicting adverse health effects of the environmental agents57. Initially, the classification k Nearest Neighbor (kNN) QSAR modeling method was applied to the HTS data only for the curated dataset of 384 compounds. The resulting models had prediction accuracies for training, test (containing 275 compounds together), and external validation (109 compounds) sets as high as 89%, 71%, and 74%, respectively. We then asked if HTS results could be of value in predicting rodent carcinogenicities. We identified 383 compounds for which data were available from both the Berkeley Carcinogenic Potency Database and NTP-HTS studies. We found that compounds classified by HTS as “actives” in at least one cell line were likely to be rodent carcinogens (sensitivity 77%); however, HTS “inactives” were far less informative (specificity 46%). Using chemical descriptors only, kNN QSAR modeling resulted in 62% overall prediction accuracy for rodent carcinogenicity applied to this data set. Importantly, the prediction accuracy of the model was significantly improved (to 73%) when chemical descriptors were augmented by the HTS data, which were regarded as biological descriptors (Figure 1). Our studies suggested that combining HTS profiles with conventional chemical descriptors could considerably improve the predictive power of computational approaches in chemical toxicology.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the prediction power of QSAR models using conventional and hybrid descriptors for carcinogenicity of external compounds

5.2. Using “hybrid” descriptors for the QSIIR modeling of rodent acute toxicity

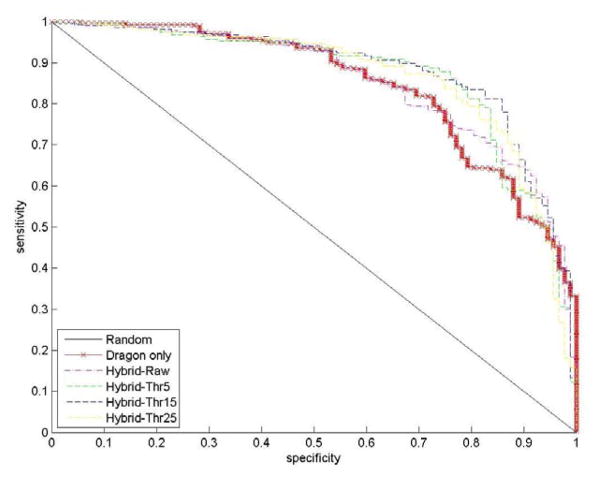

We used the cell viability qHTS data from NCGC as mentioned in the above section for the same 1,408 compounds but in 13 cell lines59. Besides the carcinogenicity, we asked if HTS results could be of value in predicting rodent acute toxicity56. For this purpose, we have identified 690 of these compounds, for which rodent acute toxicity data (i.e., toxic or non-toxic) was also available. The classification kNN QSAR modeling method was applied to these compounds using either chemical descriptors alone or as a combination of chemical and qHTS biological (hybrid) descriptors as compound features. The external prediction accuracy of models built with chemical descriptors only was 76%. In contract, the prediction accuracy was significantly improved to 85% when using hybrid descriptors. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of conventional QSAR models and different hybrid models are shown in Figure 2. The sensitivity and specificity of hybrid models are clearly better than for conventional QSAR model for predicting the same external compounds. Furthermore, the prediction coverage increased from 76% when using chemical descriptors only to 93% when q-HTS biological descriptors were also included. Our studies suggest that combining HTS profiles, especially the dose response q-HTS results, with conventional chemical descriptors could considerably improve the predictive power of computational approaches for rodent acute toxicity assessment.

Figure 2.

The ROC curves for conventional QSAR model (bold line) and different hybrid models for the same external compounds within acute toxicity modeling.

5.3. Hierarchical QSIIR modeling of rodent acute toxicity based on in vitro - in vivo relationships

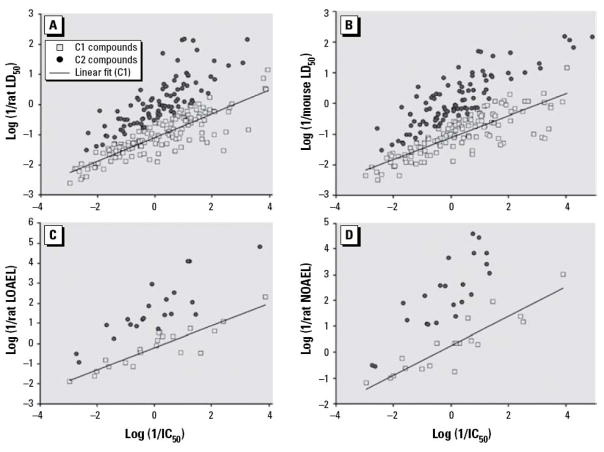

A database containing experimental in vitro IC50 cytotoxicity values and in vivo rodent LD50 values for more than 300 chemicals was compiled by the German Center for the Documentation and Validation of Alternative Methods (ZEBET). The application of conventional QSAR modeling approaches to predict mouse or rat acute LD50 from chemical descriptors of ZEBET compounds yielded no statistically significant models60. Furthermore, analysis of these data showed the correlation between IC50 and LD50 is obscure60. However, a linear IC50 vs. LD50 correlation could be established for a fraction of compounds. To capitalize on this observation, a novel two-step modeling approach was developed as follows. First, all chemicals are partitioned into two groups based on the relationship between IC50 and LD50 values: one group is formed by compounds with linear IC50 vs. LD50 relationship, and another group consists of the remaining compounds. Second, conventional binary classification QSAR models are built to predict the group affiliation based on chemical descriptors only. Third, kNN continuous QSAR models are developed for each sub-class individually to predict LD50 from chemical descriptors. All models have been extensively validated using special protocols. We have found that this type of in vitro – in vivo correlations could be established not only between cytotoxicity and rat acute toxicity (Figure 3a) but also between cytotoxicity and other types of rodent toxicity (Figure 3b–d), including two types of low dose toxicity endpoints: rat Low Observed Adverse Effect Level (LOAEL) and No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL) 55.

Figure 3.

The identification of the baseline correlation between cytotoxicity (IC50) and various types of in vivo toxicity testing results. (A) Rat LD50. (B) Mouse LD50. (C) Rat LOAEL. (D) Rat NOAEL. C1, class 1; C2, class 2.

6. Conclusion

In the past fifteen years, innovative technologies that enable rapid synthesis and high throughput screening of large libraries of compounds have advanced the risk assessment to a new stage. As a result, there has been a huge increase in the number of compounds available on a routine basis to quickly screen for novel drug candidates against new targets or pathways. This growth creates new challenges for QSAR modeling such as developing novel approaches for the analysis and visualization of large databases of screening data, novel biologically relevant chemical diversity or similarity measures, and novel tools to utilize the diverse HTS biological profiles of compounds to ensure high predictive toxicity models. Application studies discussed in this chapter have proved that integrating biological data as descriptors in the QSAR model development could be beneficial for the resulted toxicity models, especially for some specific animal toxicity endpoints. This effort extended the traditional concept of QSAR to QSIIR and may be applied for developing widely accessible and reliable computational toxicity predictors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported, in part, by grants from EPA (RD832720 and RD833825) and The Johns Hopkins Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing (2010-17).

Reference List

- 1.Kola I, Landis J. Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(8):711–715. doi: 10.1038/nrd1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inglese J, Auld DS, Jadhav A, Johnson RL, Simeonov A, Yasgar A, Zheng W, Austin CP. Quantitative high-throughput screening: a titration-based approach that efficiently identifies biological activities in large chemical libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(31):11473–11478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheeseman MA. Thresholds as a unifying theme in regulatory toxicology. Food Addit Contam. 2005;22(10):900–906. doi: 10.1080/02652030500150143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riley RJ, Kenna JG. Cellular models for ADMET predictions and evaluation of drug-drug interactions. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2004;7(1):86–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dix DJ, Houck KA, Martin MT, Richard AM, Setzer RW, Kavlock RJ. The ToxCast program for prioritizing toxicity testing of environmental chemicals. Toxicol Sci. 2007;95(1):5–12. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang C, Valerio LG, Jr, Arvidson KB. Computational toxicology approaches at the US Food and Drug Administration. Altern Lab Anim. 2009;37(5):523–531. doi: 10.1177/026119290903700509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valerio LG., Jr In silico toxicology for the pharmaceutical sciences. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;241(3):356–370. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dash A, Inman W, Hoffmaster K, Sevidal S, Kelly J, Obach RS, Griffith LG, Tannenbaum SR. Liver tissue engineering in the evaluation of drug safety. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5(10):1159–1174. doi: 10.1517/17425250903160664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park MV, Lankveld DP, van LH, de Jong WH. The status of in vitro toxicity studies in the risk assessment of nanomaterials. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2009;4(6):669–685. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durham SK, Pearl GM. Computational methods to predict drug safety liabilities. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2001;4(1):110–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobson-Kram D, Contrera JF. Genetic toxicity assessment: employing the best science for human safety evaluation. Part I: Early screening for potential human mutagens. Toxicol Sci. 2007;96(1):16–20. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muster W, Breidenbach A, Fischer H, Kirchner S, Muller L, Pahler A. Computational toxicology in drug development. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13(7–8):303–310. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailey AB, Chanderbhan R, Collazo-Braier N, Cheeseman MA, Twaroski ML. The use of structure-activity relationship analysis in the food contact notification program. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2005;42(2):225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valerio L., Jr Tools for evidence-based toxicology: computational-based strategies as a viable modality for decision support in chemical safety evaluation and risk assessment. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2008;27(10):757–760. doi: 10.1177/0960327108097689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snyder RD. An update on the genotoxicity and carcinogenicity of marketed pharmaceuticals with reference to in silico predictivity. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2009;50(6):435–450. doi: 10.1002/em.20485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zvinavashe E, Murk AJ, Rietjens IM. On the number of EINECS compounds that can be covered by (Q)SAR models for acute toxicity. Toxicol Lett. 2009;184(1):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zvinavashe E, Murk AJ, Rietjens IM. Promises and Pitfalls of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship Approaches for Predicting Metabolism and Toxicity. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008 doi: 10.1021/tx800252e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang C, Benz RD, Cheeseman MA. Landscape of current toxicity databases and database standards. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2006;9(1):124–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Young DM, Martin TM, Venkatapathy R, Harten P. Are the Chemical Structures in Your QSAR Correct. QSAR Comb Sci. 2008;27:1337–1345. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fourches D, Muratov E, Tropsha A. Trust, But Verify: On the Importance of Chemical Structure Curation in Cheminformatics and QSAR Modeling Research. J Chem Inf Model. 2010 doi: 10.1021/ci100176x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richard AM, Williams CR. Distributed structure-searchable toxicity (DSSTox) public database network: a proposal. Mutat Res. 2002;499(1):27–52. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(01)00289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Judson R, Richard A, Dix DJ, Houck K, Martin M, Kavlock R, Dellarco V, Henry T, Holderman T, Sayre P, Tan S, Carpenter T, Smith E. The toxicity data landscape for environmental chemicals. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(5):685–695. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang C, Richard AM, Cross KP. The Art of Data Mining the Minefields of Toxicity Databases to Link Chemistry to Biology. Curr Comput -Aided Drug Des. 2006;2:135–150. [Google Scholar]

- 24.PubChem. 2008 http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- 25.Knudsen TB, Martin MT, Kavlock RJ, Judson RS, Dix DJ, Singh AV. Profiling Developmental Toxicity of 387 Environmental Chemicals Using EPA’s Toxicity Reference Database (ToxRefDB) Birth Defects Research Part A-Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 2009;85(5):406. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin MT, Judson RS, Reif DM, Kavlock RJ, Dix DJ. Profiling Chemicals Based on Chronic Toxicity Results from the US EPA ToxRef Database. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2009;117(3):392–399. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ToxRefDB. 2010 http://actor.epa.gov/toxrefdb/faces/Home.jsp.

- 28.FDA Liver Side Effect. 2010 http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/CDER/ucm092203.htm.

- 29.ChEMBL. 2010 www.ebi.ac.uk/chembldb/index.php.

- 30.ToxCast. 2010 www.epa.gov/comptox/toxcast/

- 31.Fonger GC, Stroup D, Thomas PL, Wexler P. TOXNET: A computerized collection of toxicological and environmental health information. Toxicol Ind Health. 2000;16(1):4–6. doi: 10.1177/074823370001600101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shukla SJ, Huang R, Austin CP, Xia M. The future of toxicity testing: a focus on in vitro methods using a quantitative high-throughput screening platform. Drug Discov Today. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogers D, Hopfinger AJ. Application of Genetic Function Approximation to Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships and Quantitative Structure-Property Relationships. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 1994;34:854–866. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kubinyi H. Variable Selection in QSAR Studies. I. An Evolutionary Algorithm. Quant Struct -Act Relat. 1994;13:285–294. [Google Scholar]

- 35.So SS, Karplus M. Evolutionary optimization in quantitative structure-activity relationship: an application of genetic neural networks. J Med Chem. 1996;39(7):1521–1530. doi: 10.1021/jm9507035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.So SS, Karplus M. Genetic neural networks for quantitative structure-activity relationships: improvements and application of benzodiazepine affinity for benzodiazepine/GABAA receptors. J Med Chem. 1996;39(26):5246–5256. doi: 10.1021/jm960536o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tropsha A, Gramatica P, Gombar VK. The Importance of Being Earnest: Validation is the Absolute Essential for Successful Application and Interpretation of QSPR Models. Quant Struct Act Relat Comb Sci. 2003;22:69–77. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golbraikh A, Tropsha A. Predictive QSAR modeling based on diversity sampling of experimental datasets for the training and test set selection. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2002;16(5–6):357–369. doi: 10.1023/a:1020869118689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Norinder U. Single and Domain Made Variable Selection in 3D QSAR applications. J Chemomet. 1996;10:95–105. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zefirov NS, Palyulin VA. QSAR for boiling points of “small” sulfides. Are the “high-quality structure-property-activity regressions” the real high quality QSAR models? J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2001;41(4):1022–1027. doi: 10.1021/ci0001637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kubinyi H, Hamprecht FA, Mietzner T. Three-dimensional quantitative similarity-activity relationships (3D QSiAR) from SEAL similarity matrices. J Med Chem. 1998;41(14):2553–2564. doi: 10.1021/jm970732a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Novellino E, Fattorusso C, Greco G. Use of Comparative Molecular Field Analysis and Cluster Analysis in Series Design. Pharm Acta Helv. 1995;70:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Golbraikh A, Tropsha A. Beware of q2! J Mol Graph Model. 2002;20(4):269–276. doi: 10.1016/s1093-3263(01)00123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Golbraikh A, Shen M, Xiao Z, Xiao YD, Lee KH, Tropsha A. Rational selection of training and test sets for the development of validated QSAR models. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2003;17(2–4):241–253. doi: 10.1023/a:1025386326946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stouch TR, Kenyon JR, Johnson SR, Chen XQ, Doweyko A, Li Y. In silico ADME/Tox: why models fail. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2003;17(2–4):83–92. doi: 10.1023/a:1025358319677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson SR. The trouble with QSAR (or how I learned to stop worrying and embrace fallacy) J Chem Inf Model. 2008;48(1):25–26. doi: 10.1021/ci700332k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lombardo F, Gifford E, Shalaeva MY. In silico ADME prediction: data, models, facts and myths. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2003;3(8):861–875. doi: 10.2174/1389557033487629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klopman G, Zhu H, Ecker G, Chiba P. MCASE study of the multidrug resistance reversal activity of propafenone analogs. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2003;17(5–6):291–297. doi: 10.1023/a:1026124505322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stoner CL, Gifford E, Stankovic C, Lepsy CS, Brodfuehrer J, Prasad JVNV, Surendran N. Implementation of an ADME enabling selection and visualization tool for drug discovery. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2004;93(5):1131–1141. doi: 10.1002/jps.20020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mayer P, Reichenberg F. Can highly hydrophobic organic substances cause aquatic baseline toxicity and can they contribute to mixture toxicity? Environ Toxicol Chem. 2006;25(10):2639–2644. doi: 10.1897/06-142r.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Forsby A, Blaauboer B. Integration of in vitro neurotoxicity data with biokinetic modelling for the estimation of in vivo neurotoxicity. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2007;26(4):333–338. doi: 10.1177/0960327106072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schirmer K, Tanneberger K, Kramer NI, Volker D, Scholz S, Hafner C, Lee LE, Bols NC, Hermens JL. Developing a list of reference chemicals for testing alternatives to whole fish toxicity tests. Aquat Toxicol. 2008;90(2):128–137. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piersma AH, Janer G, Wolterink G, Bessems JG, Hakkert BC, Slob W. Quantitative extrapolation of in vitro whole embryo culture embryotoxicity data to developmental toxicity in vivo using the benchmark dose approach. Toxicol Sci. 2008;101(1):91–100. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sjostrom M, Kolman A, Clemedson C, Clothier R. Estimation of human blood LC50 values for use in modeling of in vitro-in vivo data of the ACuteTox project. Toxicol In Vitro. 2008;22(5):1405–1411. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu H, Ye L, Richard A, Golbraikh A, Wright FA, Rusyn I, Tropsha A. A novel two-step hierarchical quantitative structure-activity relationship modeling work flow for predicting acute toxicity of chemicals in rodents. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(8):1257–1264. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0800471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sedykh A, Zhu H, Tang H, Zhang L, Rusyn I, Richard A, Tropsha A. The Use of Dose-Response qHTS Data as Biological Descriptors Improves the Prediction Accuracy of QSAR Models of Acute Rat Toxicity. Environ Health Perspect. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002476. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu H, Rusyn I, Richard AM, Tropsha A. Use of Cell Viability Assay Data Improves the Prediction Accuracy of Conventional Quantitative Structure Activity Relationship Models of Animal Carcinogenicity. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(4):506–513. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thomas CJ, Auld DS, Huang R, Huang W, Jadhav A, Johnson RL, Leister W, Maloney DJ, Marugan JJ, Michael S, Simeonov A, Southall N, Xia M, Zheng W, Inglese J, Austin CP. The pilot phase of the NIH Chemical Genomics Center. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009;9(13):1181–1193. doi: 10.2174/156802609789753644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xia M, Huang R, Witt KL, Southall N, Fostel J, Cho MH, Jadhav A, Smith CS, Inglese J, Portier CJ, Tice RR, Austin CP. Compound cytotoxicity profiling using quantitative high-throughput screening. Environ Health Perspect. 2008;116(3):284–291. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Report of the International Workshop on In Vitro Methods for Assessing Acute Systemic Toxicity NIH Publication No: 01-4499: 01.