Abstract

Tinnitus is a common phantom sensation resulting most often from sensory deprivation, and for which little knowledge on the molecular mechanisms exists. While the existing evidence for a genetic influence on the condition has been until now sparse and underpowered, recent data suggest that specific forms of tinnitus have a strong genetic component revealing that not all tinnitus percepts are alike, at least in how they are genetically driven. These new findings pave the way for a better understanding on how phantom sensations are molecularly driven and call for international biobanking efforts.

Keywords: tinnitus, genetics, heritability, subtype, neuropsychiatry, GWAS (genome-wide association study), whole exome sequencing

Perspective

For decades, tinnitus was considered a consequence of environmental factors, with low genetic contribution. The numerous etiologies, such as aging (presbycusis), noise exposure, stress, hypertension, diabetes, ototoxic medications, temporomandibular joint disorders, traumatic or ischemic damage, vascular problems, middle-ear problems, and the complex pathophysiology involving peripheral and central auditory and non-auditory structures, have led to the belief that tinnitus is a consequence of some other disease.

The knowledge on the genetic basis of tinnitus was recently reviewed (Vona et al., 2017) and phenotyping strategies have been proposed based on the assumption that tinnitus should be considered as an ensemble of sub-entities called subtypes (Lopez-Escamez et al., 2016). A small familial aggregation study (n = 198 families) found no obvious heritability (Hendrickx et al., 2007), and the first large population-based family study (n = 52,045) made an estimate of heritability of 0.11 (Kvestad et al., 2010). But a recent twin study revealed a higher heritability of 0.4, indicating that a larger fraction of the variance can be due to genetic variants than previously reported (Bogo et al., 2016). Such discrepancies may originate from differences in the design and formulation of the questionnaires, which have been found to vary greatly in prevalence studies on tinnitus (McCormack et al., 2016).

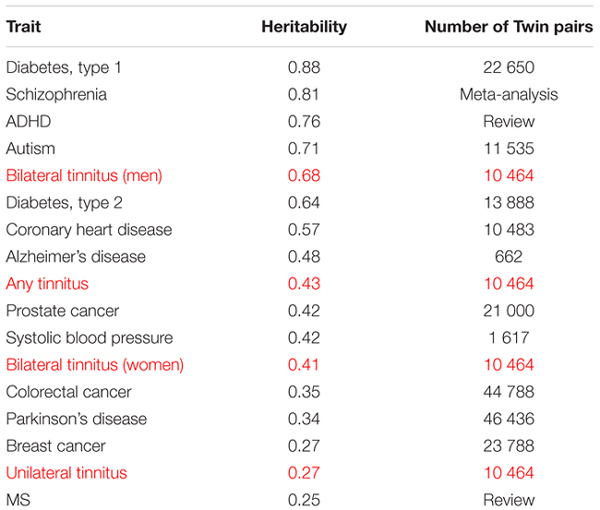

The tinnitus phenotype could also be grounds for diverging heritability values, but what defines a tinnitus phenotype is highly debated. We indeed consider that a more precise definition of a homogeneous phenotype will be essential in the design of genetic studies. A larger twin study performed by members of the TINNET1 consortium recently considered the laterality of tinnitus as a potential genetic subtype (Maas et al., 2017). A key finding was that bilateral tinnitus had higher heritability than unilateral tinnitus. The study was based on self-reported data from the Swedish Twin Registry, one of the largest twin registries in the world (Lichtenstein et al., 2002, 2006; Pedersen et al., 2002; van Dongen et al., 2012). Of a total of 70,186 twins that answered questions related to tinnitus, 15% of them experienced tinnitus. 10,464 concordant or discordant pairs for tinnitus were identified, in which 6,990 subjects had tinnitus. When considering tinnitus as a whole, a moderate genetic contribution (near 40%) was found (Bogo et al., 2016). However, when twins were stratified – based on tinnitus experienced in one ear (unilateral) or in both ears (bilateral) as well as on gender – bilateral tinnitus reached a heritability of 0.68 in men (Maas et al., 2017). Such values are close to the levels of heritability for schizophrenia and attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD), two well known heritable conditions (Table 1). Although more work is required for establishing the contribution of hearing loss in such high heritability values (e.g., by including exhaustive auditory data), these findings open the possibility of specific forms of tinnitus being more genetically driven than others and pave the way for future genetic studies considering subtypes. These findings, however, need to be replicated in other twin cohorts as well as familial studies.

Table 1.

Classification of tinnitus heritability against other disorders.

|

Modified from van Dongen et al. (2012) with permission from the Nature Publishing Group. Tinnitus values are marked in red.

In line with genetic association studies of other complex traits, published studies to find genetic markers for chronic tinnitus patients in candidate genes have been underpowered (n = 95–288) and failed to identify robustly associated genetic variants (Sand et al., 2010, 2011, 2012a,b; Gallant et al., 2013). In spite of a lowly powered tinnitus group (N = 167) and no significant associations found, a recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) identified some pathways (e.g., oxidative stress, endoplasmatic reticulum stress, and serotonin reception mediated signaling) potentially involved in tinnitus (Gilles et al., 2017). Supporting the need of better characterizing the tinnitus cases, Pawelczyk and colleagues investigated 99 single nucleotide polymorphisms targeting 10 genes involved in the potassium recycling pathway in the inner ear (128 tinnitus cases and 498 controls both exposed to occupational noise) (Pawelczyk et al., 2012). However, two of the identified SNPs were not subjected to multiple testing and were thus considered nominally significant. An important lesson from GWAS on other complex traits, such as schizophrenia and major depressive disorder (Sullivan et al., in press), is that far larger sample sizes are needed in order to identify genome-wide significant genetic variants. Therefore, an important next step in the search for genetic variants associated with tinnitus will be to perform joint GWAS analysis of thousands of tinnitus patients and healthy controls.

Since familial tinnitus is a rare condition, the selection of multiplex tinnitus families, in addition to unrelated cases and controls, for exome sequencing, is another potential strategy to be used for the discovery of genes involved in tinnitus. This strategy has been successful in the identification of DTNA, PRKCB, SEMA3D and DPT in autosomal dominant Meniere disease (Requena et al., 2015; Martin-Sierra et al., 2016, 2017).

With tinnitus being a condition with highly unmet clinical needs (Cederroth et al., 2013), the recent identification of a high heritability opens door to exciting research. Since it is more than likely that tinnitus is a polygenic trait and it will require the study of several thousand samples, audiologists and ENT doctors should optimize their phenotyping strategies for instance by using high frequency audiometry and multivariate questionnaire data (Muller et al., 2016; Schlee et al., 2017), initiate incentives to allocate a specific ICD-code for bilateral tinnitus, and start biobanking samples (Lopez-Escamez et al., 2016). Regarding the latter, since it is not custom for an ENT clinic to collect samples for DNA biobanking, guidelines should emerge to promote good practice (Fuller et al., 2017) and enable the creation of a large consortium to join efforts to decipher the genetic basis of tinnitus.

Author Contributions

CC conceived the paper and prepared the table. CC co-wrote the paper with JL-E. AK and PS helped to develop the scientific arguments. All authors played a role in writing the manuscript and approved the final version.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding. CC has received funding from Tysta Skolan, Karolinska Institutet, Lars Hiertas Minne, Magnus Bergvalls Stiftelserna, Hörselforskningsfonden, and Loo och Hans Ostermans. The work was supported by an independent research program funded under the Biomedicine and Molecular Biosciences European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST) Action framework (TINNET BM1306).

References

- Bogo R., Farah A., Karlsson K. K., Pedersen N. L., Svartengren M., Skjonsberg A. (2016). Prevalence, incidence proportion, and heritability for tinnitus: a longitudinal twin study. Ear Hear. 38 292–300. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cederroth C. R., Canlon B., Langguth B. (2013). Hearing loss and tinnitus–are funders and industry listening? Nat. Biotechnol. 31 972–974. 10.1038/nbt.2736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller T. E., Haider H. F., Kikidis D., Lapira A., Mazurek B., Norena A., et al. (2017). Different teams, same conclusions? A systematic review of existing clinical guidelines for the assessment and treatment of tinnitus in adults. Front. Psychol. 8:206 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant E., Francey L., Fetting H., Kaur M., Hakonarson H., Clark D., et al. (2013). Novel COCH mutation in a family with autosomal dominant late onset sensorineural hearing impairment and tinnitus. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 34 230–235. 10.1016/j.amjoto.2012.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles A., Van Camp G., Van de Heyning P., Fransen E. (2017). A pilot genome-wide association study identifies potential metabolic pathways involved in tinnitus. Front. Neurosci. 11:71 10.3389/fnins.2017.00071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickx J. J., Huyghe J. R., Demeester K., Topsakal V., Van Eyken E., Fransen E., et al. (2007). Familial aggregation of tinnitus: a European multicentre study. B-ENT 3(Suppl. 7), 51–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvestad E., Czajkowski N., Engdahl B., Hoffman H. J., Tambs K. (2010). Low heritability of tinnitus: results from the second Nord-Trondelag health study. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 136 178–182. 10.1001/archoto.2009.220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P., De Faire U., Floderus B., Svartengren M., Svedberg P., Pedersen N. L. (2002). The Swedish Twin Registry: a unique resource for clinical, epidemiological and genetic studies. J. Intern. Med. 252 184–205. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01032.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenstein P., Sullivan P. F., Cnattingius S., Gatz M., Johansson S., Carlstrom E., et al. (2006). The Swedish Twin Registry in the third millennium: an update. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 9 875–882. 10.1375/183242706779462444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Escamez J. A., Bibas T., Cima R. F., Van de Heyning P., Knipper M., Mazurek B., et al. (2016). Genetics of tinnitus: an emerging area for molecular diagnosis and drug development. Front. Neurosci. 10:377 10.3389/fnins.2016.00377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas I. L., Bruggemann P., Requena T., Bulla J., Edvall N. K., Hjelmborg J. V., et al. (2017). Genetic susceptibility to bilateral tinnitus in a Swedish twin cohort. Genet Med. 10.1038/gim.2017.4 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Sierra C., Gallego-Martinez A., Requena T., Frejo L., Batuecas-Caletrio A., Lopez-Escamez J. A. (2017). Variable expressivity and genetic heterogeneity involving DPT and SEMA3D genes in autosomal dominant familial Meniere’s disease. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 25 200–207. 10.1038/ejhg.2016.154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Sierra C., Requena T., Frejo L., Price S. D., Gallego-Martinez A., Batuecas-Caletrio A., et al. (2016). A novel missense variant in PRKCB segregates low-frequency hearing loss in an autosomal dominant family with Meniere’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 25 3407–3415. 10.1093/hmg/ddw183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack A., Edmondson-Jones M., Somerset S., Hall D. (2016). A systematic review of the reporting of tinnitus prevalence and severity. Hear. Res. 337 70–79. 10.1016/j.heares.2016.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller K., Edvall N. K., Idrizbegovic E., Huhn R., Cima R., Persson V., et al. (2016). Validation of online versions of tinnitus questionnaires translated into Swedish. Front. Aging Neurosci. 8:272 10.3389/fnagi.2016.00272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawelczyk M., Rajkowska E., Kotylo P., Dudarewicz A., Van Camp G., Sliwinska-Kowalska M. (2012). Analysis of inner ear potassium recycling genes as potential factors associated with tinnitus. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 25 356–364. 10.2478/S13382-012-0061-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N. L., Lichtenstein P., Svedberg P. (2002). The Swedish Twin Registry in the third millennium. Twin Res. 5 427–432. 10.1375/136905202320906219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Requena T., Cabrera S., Martin-Sierra C., Price S. D., Lysakowski A., Lopez-Escamez J. A. (2015). Identification of two novel mutations in FAM136A and DTNA genes in autosomal-dominant familial Meniere’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24 1119–1126. 10.1093/hmg/ddu524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sand P. G., Langguth B., Itzhacki J., Bauer A., Geis S., Cardenas-Conejo Z. E., et al. (2012a). Resequencing of the auxiliary GABA(B) receptor subunit gene KCTD12 in chronic tinnitus. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 6:41 10.3389/fnsys.2012.00041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sand P. G., Langguth B., Kleinjung T. (2011). Deep resequencing of the voltage-gated potassium channel subunit KCNE3 gene in chronic tinnitus. Behav. Brain Funct. 7:39 10.1186/1744-9081-7-39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sand P. G., Langguth B., Schecklmann M., Kleinjung T. (2012b). GDNF and BDNF gene interplay in chronic tinnitus. Int. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Genet. 3 245–251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sand P. G., Luettich A., Kleinjung T., Hajak G., Langguth B. (2010). An examination of KCNE1 mutations and common variants in chronic tinnitus. Genes 1 23–37. 10.3390/genes1010023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlee W., Hall D., Edvall N. K., Langguth B., Canlon B., Cederroth C. R. (2017). Visualization of global disease burden for the optimization of patient management and treatment. Front. Med. 4:86 10.3389/fmed.2017.00086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan P. F., Agrawal A., Bulik C. M., Andreassen O. A., Børglum A. D., Breen G., et al. (in press). Psychiatric genomics: an update and an agenda. Am. J. Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dongen J., Slagboom P. E., Draisma H. H., Martin N. G., Boomsma D. I. (2012). The continuing value of twin studies in the omics era. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13 640–653. 10.1038/nrg3243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vona B., Nanda I., Shehata-Dieler W., Haaf T. (2017). Genetics of tinnitus: still in its infancy. Front. Neurosci. 11:236 10.3389/fnins.2017.00236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]