Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD), the most common neurodegenerative disorder, is characterized by neurofibrillary tangles, synaptic impairments, and loss of neurons. Oligomers of β-amyloid (Aβ) are widely accepted as the main neurotoxins to induce oxidative stress and neuronal loss in AD. In this study, we discovered that fucoxanthin, a marine carotenoid with antioxidative stress properties, concentration dependently prevented Aβ oligomer-induced increase of neuronal apoptosis and intracellular reactive oxygen species in SH-SY5Y cells. Aβ oligomers inhibited the prosurvival phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt cascade and activated the proapoptotic extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway. Moreover, inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK) synergistically prevented Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal death, suggesting that the PI3K/Akt and ERK pathways might be involved in Aβ oligomer-induced neurotoxicity. Pretreatment with fucoxanthin significantly prevented Aβ oligomer-induced alteration of the PI3K/Akt and ERK pathways. Furthermore, LY294002 and wortmannin, two PI3K inhibitors, abolished the neuroprotective effects of fucoxanthin against Aβ oligomer-induced neurotoxicity. These results suggested that fucoxanthin might prevent Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss and oxidative stress via the activation of the PI3K/Akt cascade as well as inhibition of the ERK pathway, indicating that further studies of fucoxanthin and related compounds might lead to a useful treatment of AD.

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD), one of the most common neurodegenerative disorders affected aging populations, is characterized by the loss of functional neurons in the brain and the progressive impairments of learning and memory [1]. Although the mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of AD are not clearly elucidated, recent studies suggested that soluble β-amyloid (Aβ) oligomers are the main neurotoxic species that induce neuronal death and oxidative stress at the early stage of this disease [2, 3]. Aβ oligomers, aggregated from Aβ monomers, could induce neuronal apoptosis via increasing oxidative stress, possibly as a result of altered regulation of signaling pathways [4–6]. In neurons, Aβ oligomers substantially increase the level of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) [6]. Moreover, Aβ oligomers were reported to inhibit the prosurvival phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling pathway, overactivate the downstream glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), and induce neuronal death in vitro [4]. Furthermore, Aβ oligomers could act on the proapoptotic mitogen activated protein kinase (MEK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway, leading to neuronal apoptosis [5]. Therefore, molecules which could concurrently regulate oxidative stress and signaling pathways might produce neuroprotective effects against Aβ oligomers.

Fucoxanthin, a marine carotenoid mainly extracted from edible brown seaweeds, was reported to possess beneficial biological effects, including antioxidative stress and anti-inflammation activities [7, 8]. We have previously reported that fucoxanthin can inhibit acetylcholinesterase in vitro and attenuate scopolamine-induced cognitive impairments in mice, therefore suggesting that fucoxanthin might be useful to treat AD [9]. Recent studies have shown that fucoxanthin can ameliorate Aβ monomer-induced cell death in microglia and cortical neurons [10, 11]. Moreover, fucoxanthin was reported to inhibit Aβ precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 (BACE-1), an enzyme that cleaves the Aβ precursor protein into Aβ monomers [12]. Taken together, these reports suggest that fucoxanthin might inhibit Aβ-mediated neurotoxicity. However, it remains unknown whether fucoxanthin can prevent Aβ oligomer-induced neurotoxicity, and moreover, how fucoxanthin is able to produce neuroprotective effects in vitro.

In this study, we have shown for the first time that fucoxanthin significantly attenuates Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal apoptosis as well as the increase of intracellular ROS in SH-SY5Y cells. We have also demonstrated that fucoxanthin concurrently produced neuroprotective effects possibly via regulating prosurvival PI3K/Akt and proapoptotic ERK pathways.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Fucoxanthin was purified from Sargassum horneri according to our published procedures [9]. Briefly, a fucoxanthin-rich solution was first obtained by extraction with ethanol (ethanol-to-sample ratio 1 : 4) at 30°C for 2 h. The solution was concentrated at 25°C. Wastes including lipid and chlorophylls were precipitated when the content of ethanol reached approximately 63%. Fucoxanthin was obtained by precipitation when the ethanol concentration reached near 40%. The purity of fucoxanthin was over 90% as examined by high-performance liquid chromatography.

Aβ1–42 peptide was purchased from GL Biochem (Shanghai, China). 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) was obtained from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA). Soluble Aβ oligomers were prepared as previously described [13, 14]. Briefly, Aβ1–42 peptide was dissolved in HFIP to form Aβ monomers. After thoroughly vortexing, 1 mM Aβ monomer solution was aliquoted in 100 μl stock, and stored at −20°C. Milli-Q water (900 μl) was added to 100 μl Aβ1–42 solution before the experiments. Aβ solution was further spin-vacuumed and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. HFIP was completely evaporated to obtain the solution of 50 μM Aβ. The Aβ solution was kept at room temperature under constant stirring for 48 h and centrifuged at 14000g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant (about 900 μl) which contained mainly soluble Aβ oligomers was collected.

SB415286 was obtained from Sigma Chemicals. U0126, wortmannin, and LY294002 were received from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA, USA). Antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA).

2.2. SH-SY5Y Cells Culture

SH-SY5Y cells were maintained in high glucose modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin (100 U/ml)/streptomycin (100 μg/ml) at 37°C with 5% CO2. The medium was refreshed every two days. Before experiments, SH-SY5Y cells were seeded in DMEM with 1% fetal bovine serum for 24 h.

2.3. Cell Viability Measurements

Cell viability was measured by 3(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2.5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay based on our previous protocol [15, 16]. Briefly, 10 μl MTT (5 mg/ml) was added to each well in 96-well (100 μl medium/well) plates. Then, plates were incubated at 37°C for 4 h, and 100 μl solvate (0.01 N HCl in 10% SDS) was added. After 16–20 h, the absorbance of samples was measured at a wavelength of 570 nm with 655 nm as the reference wavelength.

2.4. Fluorescein Diacetate (FDA)/Propidium Iodide (PI) Double Staining

FDA/PI double staining was performed according to our previous publication [17]. Viable cells were visualized by the fluorescein formed from FDA by esterase activity in the cytoplasm. Nonviable cells were visualized by PI, which only penetrates the membranes of dead cells. Cells were examined after incubation with 10 μg/ml FDA and 5 μg/ml PI at 37°C for 15 min. Images were obtained by UV light microscopy and compared with those taken under a phase-contrast microscopy (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). To quantitatively evaluate cell viability, images of each well were taken from five randomly selected fields, and the number of FDA-positive and PI-positive cells was counted. The percentage of cell viability was analyzed using the equation % of cell viability = [number of DFA‐cell positive cells / (number of PI‐positive cells + number of DFA‐positive cells)] × 100%.

2.5. Hoechst Staining

Chromatin condensation was measured by staining the cell nuclei with Hoechst 33342 as previously described [18, 19]. Cells in 6-well (2 ml medium/well) plates were washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, fixed, and membrane permeabilized with 4% formaldehyde in 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min. Cells were then stained with Hoechst 33342 (5 μg/ml, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China) at 4°C for 5 min. Images were obtained by a fluorescence microscope at 100x magnification (Nikon). To determine the proportion of apoptotic nuclei in each group, images of each well were taken from five randomly selected fields, and the number of pyknotic nuclei and total nuclei was counted. The percentage of pyknotic nuclei was then analyzed using the equation % of pyknotic nuclei = number of pyknotic nuclei / number of total nuclei × 100%.

2.6. Intracellular ROS Measurements

The level of intracellular ROS was measured by 5-(and-6)-carboxy-2′,7′-dichiorodihydroflurescein diacetate (carboxy-H2DCF-DA, Sigma) as reported in our previous publication [20]. Briefly, cells were washed once with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with 10 μM carboxy-H2DCF-DA at 37°C for 10 min. Cells were then washed once with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and scanned with a plate reader at 485 nm excitation and 520 nm emission. Images were acquired by a fluorescence microscope (Nikon). Unless otherwise indicated, the fluorescence intensity in SH-SY5Y cells without treatment is expressed as a percentage of the control.

2.7. Western Blot Analysis

Western blotting was performed using a well-established protocol [21]. Cell lysates were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto polyvinyldifluoride membranes (Pall Corporation, New York, USA). After membrane blocking, proteins were detected by primary antibodies. After incubation at 4°C overnight, signals were obtained after incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Subsequently, blots were developed using the enhanced chemiluminescence plus kit (Beyotime, Hangzhou, China) and signals were exposed.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± SEM. Differences among groups were compared by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett's or Tukey's test. p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Fucoxanthin Effectively Attenuates Aβ Oligomer-Induced Neuronal Apoptosis in SH-SY5Y Cells

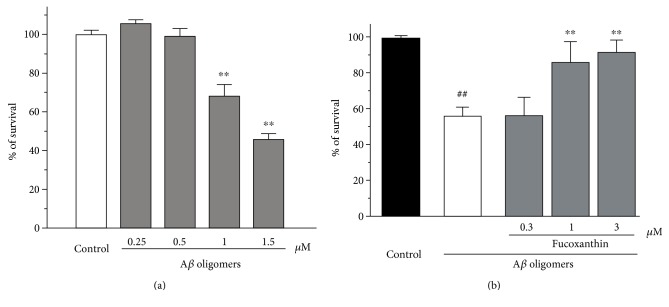

We first evaluated the neurotoxicity of Aβ oligomers in SH-SY5Y cells. It was demonstrated that 24 h treatment of Aβ oligomers at concentrations of 1–1.5 μM significantly induced neuronal death in SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 1(a)). Therefore, we used 1 μM Aβ oligomer to induce neurotoxicity in the following study.

Figure 1.

Fucoxanthin attenuated Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss as evidenced by the MTT assay. (a) Aβ oligomers induced neuronal loss in a concentration-dependent manner in SH-SY5Y cells. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with Aβ oligomers at various concentrations as indicated. After 24 h, the MTT assay was used to measure cell viability. (b) Fucoxanthin attenuates Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss in SH-SY5Y cells. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with fucoxanthin at various concentrations as indicated. After 2 h, 1 μM Aβ oligomer was added. The MTT assay was used to measure cell viability at 24 h after the addition of Aβ oligomers. Data, expressed as percentage of control were the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments; ##p < 0.01 versus the control group in (b), ∗∗p < 0.01 versus the control group in (a) and the Aβ oligomer group in (b) (ANOVA and Tukey's test).

To investigate the neuroprotective effects of fucoxanthin, SH-SY5Y cells were pretreated with 0.3–3 μM fucoxanthin for 2 h before adding Aβ oligomers. After 24 h, cell viability was analyzed. Fucoxanthin concentration-dependently attenuated Aβ oligomer-induced reduction of cell viability (Figure 1(b)). Moreover, treatment of 3 μM fucoxanthin alone for 26 h did not induce cell proliferation or cell death (data not shown).

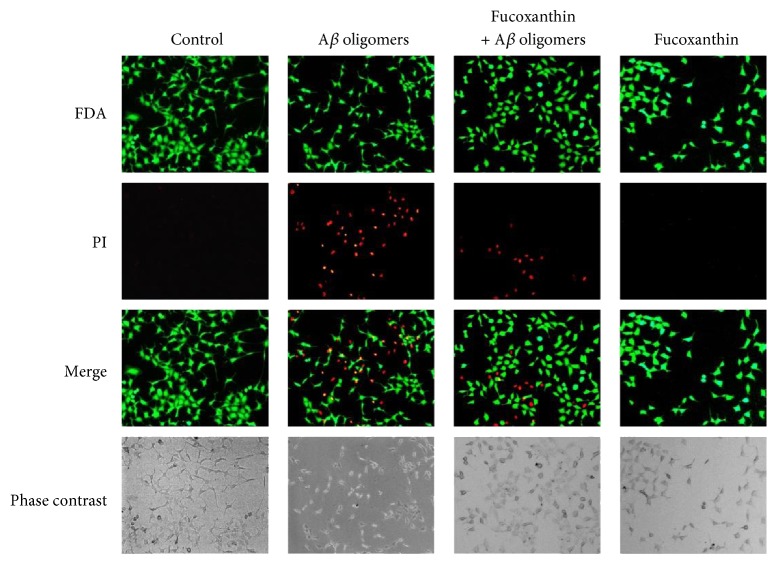

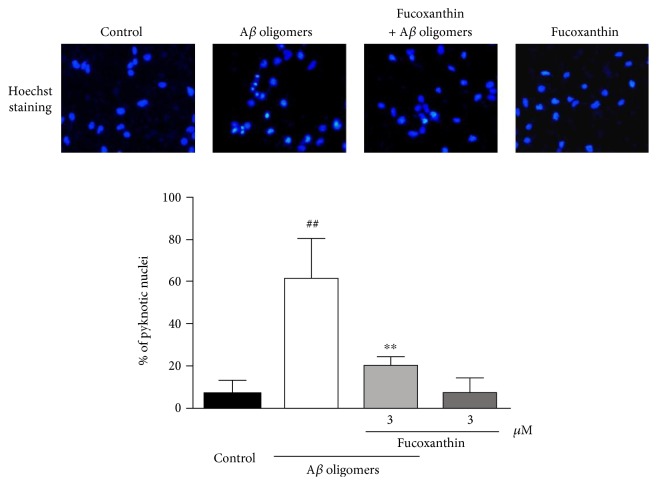

As shown in Figure 2, Aβ oligomers could substantially increase the number of PI-positive nonviable cells and decrease the number of FDA-positive viable cells when compared to the control group. This neurotoxicity of Aβ oligomers was largely prevented by fucoxanthin (Figure 2). Moreover, Aβ oligomers significantly increased the percentage of pyknotic nuclei in SH-SY5Y cells, suggesting that Aβ oligomers caused neuronal loss mainly via inducing cell apoptosis (Figure 3). Furthermore, fucoxanthin significantly decreased Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal apoptosis, as demonstrated by the decrease in the percentage of pyknotic nuclei in the fucoxanthin plus Aβ oligomer group as compared to that in the Aβ oligomer group (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Fucoxanthin attenuates Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss as evidenced by FDA/PI double staining. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 3 μM fucoxanthin. After 2 h, 1 μM Aβ oligomer was added. FDA/PI double staining was used to demonstrate FDA-positive viable cells and PI-positive nonviable cells at 24 h after the treatment of Aβ oligomers.

Figure 3.

Fucoxanthin attenuates Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal apoptosis as evidenced by Hoechst staining. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 3 μM fucoxanthin. After 2 h, 1 μM Aβ oligomer was added. Hoechst staining was used to measure the number of pyknotic nuclei with condensed chromatin at 24 h after the treatment of Aβ oligomers. Data were the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments; ##p < 0.01 versus the control group; ∗∗p < 0.01 versus the Aβ oligomer group (ANOVA and Tukey's test).

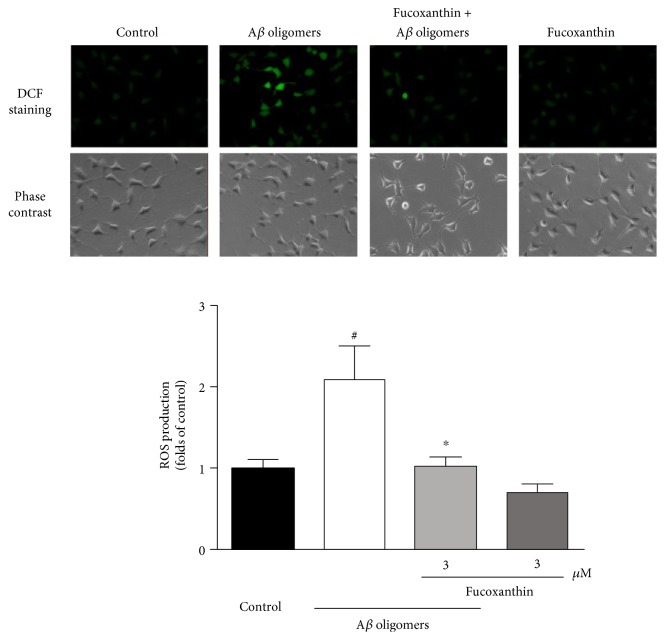

3.2. Fucoxanthin Effectively Attenuates Aβ Oligomer-Induced Increase of ROS in SH-SY5Y Cells

Aβ oligomers significantly increased the level of intracellular ROS in SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 4). This increase in ROS was significantly attenuated by treatment with 3.0 μM fucoxanthin. This finding provides additional support for the neuroprotective effects of fucoxanthin against Aβ oligomer-induced toxicity in SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Fucoxanthin attenuates Aβ oligomer-induced increase of intracellular ROS level as evidenced by carboxy-H2DCF-DA staining. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 3 μM fucoxanthin. After 2 h, 1 μM Aβ oligomer was added. Carboxy-H2DCF-DA staining was used to measure intracellular ROS level at 24 h after the treatment of Aβ oligomers. Data were the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments; #p < 0.05 versus the control group; ∗p < 0.05 versus the Aβ oligomer group (ANOVA and Tukey's test).

3.3. Concurrent Activation of the PI3K/Akt Pathway and Inhibition of the ERK Pathway Attenuate Aβ Oligomer-Induced Neuronal Loss in SH-SY5Y Cells

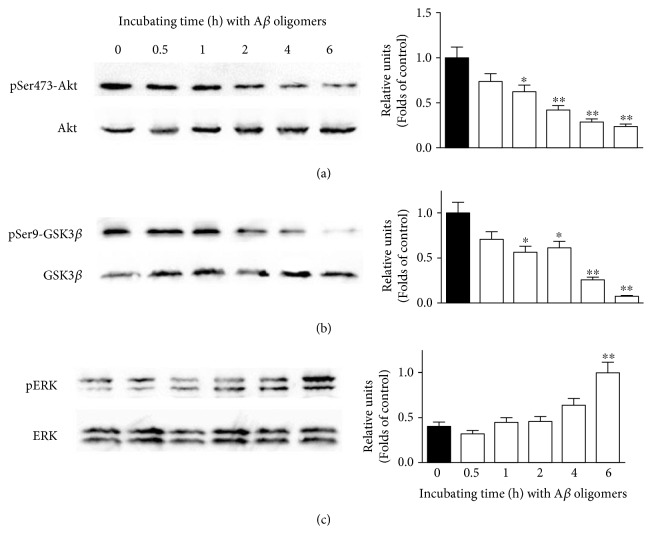

We further investigated if signaling pathways were involved in Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss in our model. We first used Western blotting analysis to explore the alterations of signaling pathways induced by Aβ oligomers. Aβ oligomers were added to SH-SY5Y cells for various durations, and the cellular proteins were extracted. It was demonstrated that Aβ oligomers time-dependently decreased the expressions of pSer473-Akt and pSer9-GSK3β, suggesting that Aβ oligomers inhibited the PI3K/Akt pathway (Figures 5(a) and 5(b)). Furthermore, Aβ oligomers also increased the expression of pERK in a time-dependent manner in SH-SY5Y cells, indicating that Aβ oligomers might activate the ERK pathway in our model (Figure 5(c)).

Figure 5.

Aβ oligomers inhibit the PI3K/Akt pathway and activate the ERK pathway in SH-SY5Y cells. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 1 μM Aβ oligomer for various durations as indicated. Western blotting analysis was used to determine the expression of (a) pSer473-Akt, (b) pSer9-GSK3β, and (c) pERK. Data were the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments; ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗p < 0.01 versus the control group (ANOVA and Tukey's test).

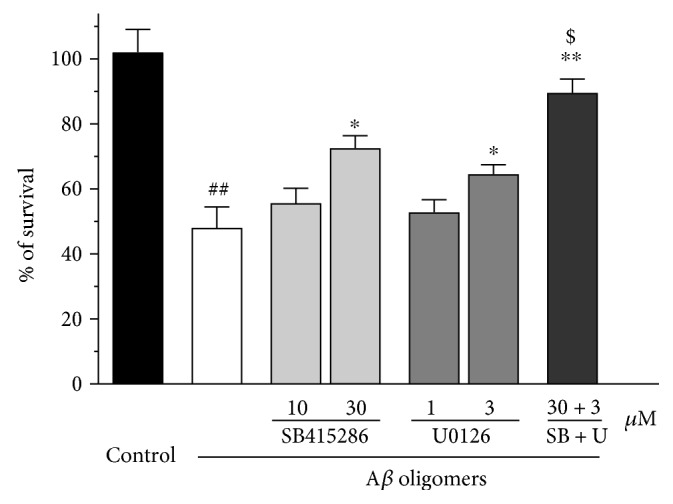

The PI3K/Akt pathway is widely accepted as a prosurvival signaling pathway, while the ERK pathway is generally considered as a proapoptotic pathway [4, 5]. To explore if the regulation of these signaling pathways could attenuate Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss, two inhibitors were used. SB415286 is a GSK3β-specific inhibitor, while U0126 is a MEK-specific inhibitor. Both SB415286 and U0126 concentrations could dependently attenuated Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss in SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 6). Moreover, the combination of SB415286 and U0126 synergistically prevented neurotoxicity induced by Aβ oligomers, suggesting that concurrently activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway and inhibition of the ERK pathway could attenuate Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss in SH-SY5Y cells (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

SB415286 and U0126 synergistically attenuates Aβoligomer-induced neuronal loss in SH-SY5Y cells. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with SB415286, a GSK3β inhibitor, and/or U0126, a MEK inhibitor, at various concentrations as indicated. After 2 h, 1 μM Aβ oligomer was added. The MTT assay was used to measure cell viability at 24 h after the treatment of Aβ oligomers. Data, expressed as percentage of control were the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments; ##p < 0.01 versus the control group, ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗p < 0.01 versus the Aβ oligomer group; $p < 0.05 versus the U0126 plus Aβ oligomer group (ANOVA and Tukey's test).

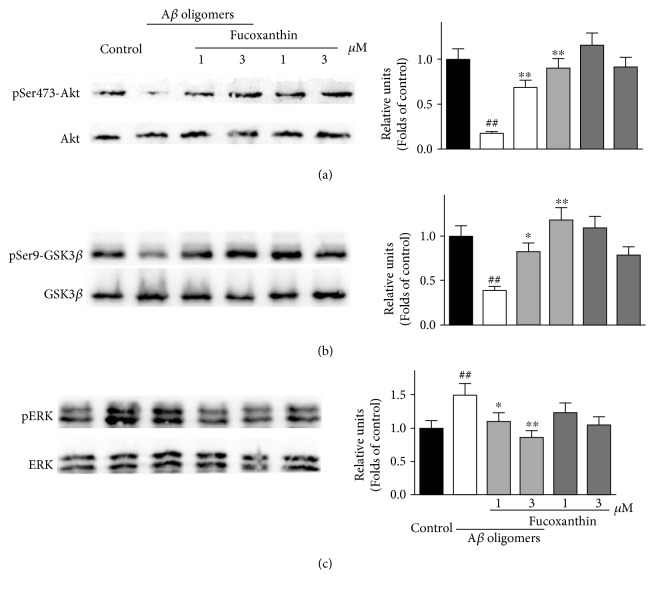

3.4. Fucoxanthin Prevents the Alterations of the PI3K/Akt and the ERK Pathways Induced by Aβ Oligomers in SH-SY5Y Cells

To study whether fucoxanthin attenuated Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss via regulating the PI3K/Akt and the ERK pathways, we used Western blotting analysis. SH-SY5Y cells were pretreated with 3 μM fucoxanthin for 2 h before adding Aβ oligomers. After 6 h, proteins were extracted. As demonstrated in Figures 7(a) and 7(b), fucoxanthin prevented Aβ oligomer-induced decrease of pSer473-Akt and pSer9-GSK3β in a concentration-dependent manner, suggesting that fucoxanthin could attenuate the inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway induced by Aβ oligomers. Moreover, fucoxanthin concentration dependently prevented Aβ oligomer-induced increase of pERK, indicating that fucoxanthin also attenuated the activation of the ERK pathway induced by Aβ oligomers (Figure 7(c)). The treatment of fucoxanthin alone did not significantly change the expressions of pSer473-Akt, pSer9-GSK3β and pERK (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Fucoxanthin prevents Aβ oligomer-induced alteration of the PI3K/Akt and the ERK pathways in a concentration-dependent manner in SH-SY5Y cells. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 1 or 3 μM fucoxanthin. After 2 h, 1 μM Aβ oligomer was added. Western blotting analysis was used to determine the expression of (a) pSer473-Akt, (b) pSer9-GSK3β, and (c) pERK at 6 h after the treatment of Aβ oligomers. Data were the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments; ##p < 0.01 versus the control group; ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗p < 0.01 versus the Aβ oligomer group (ANOVA and Tukey's test).

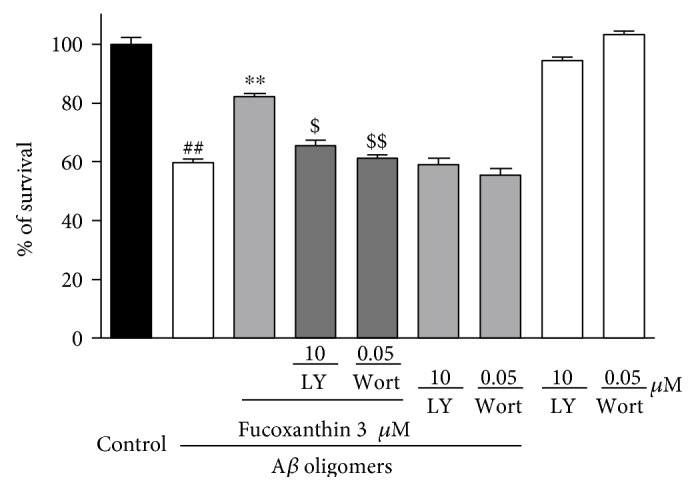

In addition, LY294002 and wortmannin, two PI3K inhibitors were used to confirm if fucoxanthin attenuated Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss via regulating the PI3K/Akt pathway. As shown in Figure 8, both PI3K inhibitors significantly abolished the neuroprotective effects of fucoxanthin against neuronal loss induced by Aβ oligomers, providing a support that fucoxanthin produced neuroprotective effects via the activation of PI3K/Akt pathway.

Figure 8.

LY294002 and wortmannin significantly abolished the neuroprotective effects of fucoxanthin against Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss in SH-SY5Y cells. SH-SY5Y cells were treated with 10 μM LY294002 (LY) or 0.05 μM wortmannin (Wort). After 0.5 h, 3 μM fucoxanthin was added. Aβ oligomers (1 μM) were added at 2 h after the addition of fucoxanthin. The MTT assay was used to measure cell viability at 24 h after the treatment of Aβ oligomers. Data, expressed as percentage of control, were the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments; ##p < 0.01 versus the control group, ∗∗p < 0.01 versus the Aβ oligomer group, and $p < 0.05 and $$p < 0.01 versus the fucoxanthin plus Aβ oligomer group (ANOVA and Tukey's test).

4. Discussion

We have reported, for the first time, that fucoxanthin significantly attenuated Aβ oligomer-induced neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells. We further demonstrated that the neuroprotective effects of fucoxanthin against Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss and oxidative stress possibly via activating the prosurvival PI3K/Akt pathway and inhibiting the proapoptotic ERK pathway, concurrently.

Aβ oligomers are widely accepted as the main neurotoxins to induce neuronal loss in the brain of AD patients [22]. However, the neurotoxicity of Aβ oligomers formed by different formation protocols varies widely in vitro [23]. In our study, we used a protocol of Aβ oligomer formation which is derived from Roger Anwyl's lab [14, 24]. We found that Aβ oligomers substantially induced neuronal apoptosis at micromolar levels in SH-SY5Y cells, which is consistent with previous publications [25, 26].

We also found that fucoxanthin at 3 μM could significantly attenuate Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss in SH-SY5Y cells, as indicated by the MTT assay, FDA/PI double staining and Hoechst staining. These results are consistent with previous publications showing that fucoxanthin at similar concentrations could prevent Aβ-induced neurotoxicity in cortical neurons and microglia [10, 11]. However, in these reports, authors used Aβ25–35 or Aβ1–42 monomers, which are much less toxic than Aβ oligomers. Moreover, the mechanisms underlying the neurotoxicity of Aβ oligomers and Aβ monomers might be different. Therefore, we further investigated how fucoxanthin attenuated neuronal loss induced by Aβ oligomers. We found that fucoxanthin significantly reversed Aβ oligomer-induced increase of intracellular ROS. Previous studies have shown that there are two hydroxy groups in the ring structure of fucoxanthin that could donate electrons or hydrogen atoms, leading to free radical scavenging and the antioxidative stress properties of fucoxanthin [27, 28]. Therefore, our results provides evidence that fucoxanthin can decrease oxidative stress in neurons, and therefore might be useful in the central nervous systems.

Previous studies have reported that Aβ oligomers could act on both prosurvival and proapoptotic pathways [29, 30]. Therefore, we studied which signaling pathways are mainly involved in Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss in our model. We found that (1) both the PI3K/Akt and the ERK pathways were altered by Aβ oligomers and (2) concurrent activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway and inhibition of the ERK pathway synergistically attenuated Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss. These results suggested that Aβ oligomers lead to neuronal loss possibly via simultaneous inhibition of the prosurvival PI3K/Akt pathway and activation of the proapoptotic ERK pathway.

We further investigated the regulation of signaling pathways by fucoxanthin. Fucoxanthin attenuated Aβ oligomer-induced decrease of pSer473-Akt and pSer9-GSK3β. Moreover, PI3K inhibitors significantly abolished the neuroprotective effects of fucoxanthin. These results suggested that fucoxanthin produced neuroprotective effects at least partially via the activation of the prosurvival PI3K/Akt pathway, which is consistence with a report that fucoxanthin activated the PI3K/Akt cascade to decrease cell injury [31]. Moreover, fucoxanthin attenuated Aβ oligomer-induced increase of pERK in SH-SY5Y cells, indicating that the inhibition of proapoptotic ERK pathway participated in the neuroprotective effects of fucoxanthin. Interestingly, neither SB415286 nor U0126 could fully prevent Aβ oligomer-induced neuronal loss in our model. However, the coapplication of SB415286 and U0126 almost fully reversed neuronal loss induced by Aβ oligomers, which is similar to that of fucoxanthin at 3 μM. These results provided support for the model that fucoxanthin concurrently modulates the PI3K/Akt and ERK pathways to produce neuroprotective effects.

Previous studies reported that oxidative stress could be initiated by many signaling pathways, such as the ERK, the PI3K/Akt, p38, and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells nuclear factor (NF-κB) cascade [32]. Besides the ERK and the PI3K pathways, could fucoxanthin act on other molecules to inhibit oxidative stress induced by Aβ oligomers? Akt is reported to act on both GSK3β and NF-κB [33]. Therefore, fucoxanthin-induced Akt activation might also regulate NF-κB to inhibit oxidative stress. And whether fucoxanthin could act on other molecules, such as NF-κB, is being investigated in our lab.

Previously, we have reported that fucoxanthin possesses the ability to inhibit acetylcholinesterase [34]. Interestingly, there is a report showing that acetylcholine could decrease the level of extracellular Aβ via activating α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChR) [35]. Moreover, many α7nAChR agonists and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are reported to inhibit Aβ neurotoxicity [36, 37]. Therefore, besides the activation of the signaling pathways, fucoxanthin might also reduce Aβ neurotoxicity via regulating acetylcholine. However, whether fucoxanthin could activate α7nAChR is being studied.

Fucoxanthin could be extracted from edible brown seaweeds. Fucoxanthin-rich functional foods are used for antiobesity treatments in Western countries [38]. A double-blind placebo-controlled human study daily using supplementation with 2.4 mg fucoxanthin showed a significantly weight loss in obese women over a 16-week period [39]. No obvious side effects were observed in this study, suggesting that fucoxanthin is quite safe for human use.

In summary, we found that fucoxanthin attenuated Aβ oligomer-induced neurotoxicity and oxidative stress possibly via the activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway and the inhibition of the ERK pathway, concurrently. Based on these findings and the safety of fucoxanthin, we anticipated that further studies of fucoxanthin and related compounds might one day lead to a useful treatment of AD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LY15H310007, LQ13B020004), the Applied Research Project on Nonprofit Technology of Zhejiang Province (2016C37110), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U1503223, 81673407, and 41306134), the Ningbo International Science and Technology Cooperation Project (2014D10019), Ningbo Municipal Innovation Team of Life Science and Health (2015C110026), National 111 Project of China, the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, Li Dak Sum Yip Yio Chin Kenneth Li Marine Biopharmaceutical Development Fund, and the K. C. Wong Magna Fund in Ningbo University. William H. Gerwick was sponsored by the Chinese National Recruitment Program of Global Experts (1000 Talents).

Abbreviations

- AD:

Alzheimer's disease

- ANOVA:

Analysis of variance

- Aβ:

β-amyloid

- BACE-1:

Aβ precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1

- carboxy-H2DCF-DA:

5-(and-6)-carboxy-2′,7′-dichiorodihydroflurescein diacetate

- ERK:

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FDA:

Fluorescein diacetate

- GSK3β:

Glycogen synthase kinase 3β

- HFIP:

1,1,1,3,3,3-Hexafluoro-2-propanol

- MEK:

Mitogen activated protein kinase

- MTT:

3(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2.5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- PI:

Propidium iodide

- PI3K:

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- ROS:

Reactive oxygen species

- α7nAChR:

α7 Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Scheltens P., Blennow K., Breteler M. M., et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 2016;388(10043):505–517. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klein W. L. Synaptotoxic amyloid-beta oligomer: a molecular basis for the cause, diagnosis, and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease? Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2013;33(Supplement 1):S49–S65. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-129039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferreira S. T., Klein W. L. The Aβ oligomer hypothesis for synapse failure and memory loss in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2011;96:529–543. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jimenez S., Torres M., Vizuete M., et al. Age-dependent accumulation of soluble amyloid beta (Abeta) oligomer reverses the neuroprotective effect of soluble amyloid precursor protein-alpha (sAPP(alpha)) by modulating phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt-GSK-3beta pathway in Alzheimer mouse model. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:18414–18425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.209718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chong Y. H., Shin Y. J., Lee E. O., Kayed R., Glabe C. G., Tenner A. J. ERK1/2 activation mediates Aβ oligomer-induced neurotoxicity via caspase-3 activation and tau cleavage in rat organotypic hippocampal slice cultures. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:20315–20325. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim B., Park J., Chang K. T., Lee D. S. Peroxiredoxin 5 prevents amyloid-beta oligomer-induced neuronal cell death by inhibiting ERK-Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fragmentation. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2016;90:184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gammone M. A., Riccioni G., D'Orazio N. Marine carotenoids against oxidative stress: effects on human health. Marine Drugs. 2015;13:6226–6246. doi: 10.3390/md13106226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gammone M. A., D'Orazio N. Anti-obesity activity of the marine carotenoid fucoxanthin. Marine Drugs. 2015;13:2196–2214. doi: 10.3390/md13042196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin J., Huang L., Yu J., et al. Fucoxanthin, a marine carotenoid, reverses scopolamine-induced cognitive impairments in mice and inhibits acetylcholinesterase in vitro. Marine Drugs. 2016;14 doi: 10.3390/md14040067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pangestuti R., Vo T. S., Ngo D. H., Kim S. K. Fucoxanthin ameliorates inflammation and oxidative reponses in microglia. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2013;61:3876–3883. doi: 10.1021/jf400015k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao X., Zhang S., An C., et al. Neuroprotective effect of fucoxanthin on β-amyloid-induced cell death. Journal of Chinese Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2015;24:467–474. doi: 10.5246/jcps.2015.07.060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung H. A., Ali M. Y., Choi R. J., Jeong H. O., Chung H. Y., Choi J. S. Kinetics and molecular docking studies of fucosterol and fucoxanthin, BACE1 inhibitors from brown algae Undaria pinnatifida and Ecklonia stolonifera. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2016;89:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang L., Huang M., Xu S., et al. Bis(propyl)-cognitin prevents beta-amyloid-induced memory deficits as well as synaptic formation and plasticity impairments via the activation of PI3-K pathway. Molecular Neurobiology. 2016;53:3832–3841. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Q., Rowan M. J., Anwyl R. Beta-amyloid-mediated inhibition of NMDA receptor-dependent long-term potentiation induction involves activation of microglia and stimulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase and superoxide. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:6049–6056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0233-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cui W., Zhang Z., Li W., et al. The anti-cancer agent SU4312 unexpectedly protects against MPP+-induced neurotoxicity via selective and direct inhibition of neuronal NOS. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2013;168:1201–1214. doi: 10.1111/bph.12004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cui W., Zhang Z. J., Hu S. Q., et al. Sunitinib produces neuroprotective effect via inhibiting nitric oxide overproduction. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2014;20:244–252. doi: 10.1111/cns.12203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu J., Zheng J., Lin J., et al. Indirubin-3-oxime prevents H2O2-induced neuronal apoptosis via concurrently inhibiting GSK3β and the ERK pathway. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 2017;37(4):655–664. doi: 10.1007/s10571-016-0402-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cui W., Zhang Z., Li W., et al. Unexpected neuronal protection of SU5416 against 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion-induced toxicity via inhibiting neuronal nitric oxide synthase. PLoS One. 2012;7, article e46253 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu S., Wang R., Cui W., et al. Inhibiting beta-amyloid-associated Alzheimer’s pathogenesis in vitro and in vivo by a multifunctional dimeric bis(12)-hupyridone derived from its natural analogue. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2015;55(4):1014–1021. doi: 10.1007/s12031-014-0458-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu S., Cui W., Zhang Z., et al. Indirubin-3-oxime effectively prevents 6OHDA-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells via activating MEF2D through the inhibition of GSK3beta. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 2015;57:561–570. doi: 10.1007/s12031-015-0638-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo B., Zheng C., Cai W., et al. Multifunction of chrysin in Parkinson’s model: anti-neuronal apoptosis, neuroprotection via activation of MEF2D, and inhibition of monoamine oxidase-B. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2016;64:5324–5333. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.6b01707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kayed R., Lasagna-Reeves C. A. Molecular mechanisms of amyloid oligomer toxicity. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2013;33(Supplement 1):S67–S78. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-129001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan D. A., Narrow W. C., Federoff H. J., Bowers W. J. An improved method for generating consistent soluble amyloid-beta oligomer preparations for in vitro neurotoxicity studies. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2010;190:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Q., Walsh D. M., Rowan M. J., Selkoe D. J., Anwyl R. Block of long-term potentiation by naturally secreted and synthetic amyloid beta-peptide in hippocampal slices is mediated via activation of the kinases c-Jun N-terminal kinase, cyclin-dependent kinase 5, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase as well as metabotropic glutamate receptor type 5. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24:3370–3378. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1633-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim K., Park K. S., Kim M. K., Choo H., Chong Y. Dicyanovinyl-substituted J147 analogue inhibits oligomerization and fibrillation of beta-amyloid peptides and protects neuronal cells from beta-amyloid-induced cytotoxicity. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry. 2015;13:9564–9569. doi: 10.1039/c5ob01463h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cameron R. T., Quinn S. D., Cairns L. S., et al. The phosphorylation of Hsp20 enhances its association with amyloid-beta to increase protection against neuronal cell death. Molecular and Cellular Neurosciences. 2014;61:46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heo S. J., Jeon Y. J. Protective effect of fucoxanthin isolated from Sargassum siliquastrum on UV-B induced cell damage. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B. 2009;95:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pangestuti R., Kim S. K. Neuroprotective effects of marine algae. Marine Drugs. 2011;9:803–818. doi: 10.3390/md9050803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim K. N., Heo S. J., Yoon W. J., et al. Fucoxanthin inhibits the inflammatory response by suppressing the activation of NF-kappaB and MAPKs in lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW 264.7 macrophages. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2010;649:369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi J. H., Kim N. H., Kim S. J., Lee H. J., Kim S. Fucoxanthin inhibits the inflammation response in paw edema model through suppressing MAPKs, Akt, and NFkappaB. Journal of Biochemical and Molecular Toxicology. 2016;30:111–119. doi: 10.1002/jbt.21769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zheng J., Piao M. J., Kim K. C., Yao C. W., Cha J. W., Hyun J. W. Fucoxanthin enhances the level of reduced glutathione via the Nrf2-mediated pathway in human keratinocytes. Marine Drugs. 2014;12:4214–4230. doi: 10.3390/md12074214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finkel T., Holbrook N. J. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi Z. M., Han Y. W., Han X. H., et al. Upstream regulators and downstream effectors of NF-kappa B in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2016;366:127–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin J. J., Huang L., Yu J., et al. Fucoxanthin, a marine carotenoid, reverses scopolamine-induced cognitive impairments in mice and inhibits acetylcholinesterase in vitro. Marine Drugs. 2016;14 doi: 10.3390/md14040067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parri H. R., Hernandez C. M., Dineley K. T. Research update: alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor mechanisms in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2011;82:931–942. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nalivaeva N. N., Turner A. J. AChE and the amyloid precursor protein (APP) - cross-talk in Alzheimer’s disease. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2016;259:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Russo P., Del Bufalo A., Frustaci A., Fini M., Cesario A. Beyond acetylcholinesterase inhibitors for treating Alzheimer’s disease: alpha 7-nAChR agonists in human clinical trials. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2014;20:6014–6021. doi: 10.2174/1381612820666140316130720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wan-Loy C., Siew-Moi P. Marine algae as a potential source for anti-obesity agents. Marine Drugs. 2016;14 doi: 10.3390/md14120222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abidov M., Ramazanov Z., Seifulla R., Grachev S. The effects of Xanthigen in the weight management of obese premenopausal women with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and normal liver fat. Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism. 2010;12:72–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]