Abstract

BACKGROUND

Chronic exposure to stress or alcohol can drive neuroadaptations that alter cognition. Alterations in cognition may contribute to alcohol use disorders by reducing cognitive control over drinking and maintenance of abstinence. Here we examined effects of combined ethanol and stress exposure on prefrontal cortex (PFC)-dependent cognition.

METHODS

Adult male C57BL/6J mice were trained to drink ethanol (15%, v/v) on a 1hr/day 1-bottle schedule. Once stable, mice were exposed to cycles of chronic intermittent ethanol (CIE) or air-control vapor exposure (Air), followed by test cycles of 1hr/day ethanol drinking. During test drinking mice received no-stress (NS) or 10 minutes of forced swim stress (FSS) 4 hours before each test. This schedule produced four experimental groups: control, Air/NS; ethanol-dependent no stress, CIE/NS; non-dependent stress, Air/FSS; or ethanol-dependent stress, CIE/FSS. After two cycles of CIE and FSS exposure we assessed PFC-dependent cognition using object/context recognition and attentional set-shifting. At the end of the study mice were perfused and brains collected for measurement of c-Fos activity in PFC and locus coeruleus (LC).

RESULTS

CIE/FSS mice escalated ethanol intake faster than CIE/NS and consumed more ethanol than Air/NS across all test cycles. After two cycles of CIE/FSS, mice showed impairments in contextual learning and extra-dimensional set shifting relative to other groups. In addition to cognitive dysfunction, CIE/FSS mice demonstrated widespread reductions in c-Fos activity within prelimbic and infralimbic PFC as well as LC.

CONCLUSION

Together, these findings show that interactions between ethanol and stress exposure rapidly lead to disruptions in signaling across cognitive networks and impairments in PFC-dependent cognitive function.

Keywords: Chronic Alcohol, Stress, Prefrontal Cortex, Attentional Set-Shifting, Contextual Memory

INTRODUCTION

Alcohol use disorders (AUD) are characterized by a transition from initial consumption to excessive drinking and dependence. Although multiple factors contribute to the development of AUDs, stress and anxiety appear to be key components. Chronic stress has been shown to increase drinking and alcohol seeking in humans and in animal models of AUDs (Becker et al. 2011; Sinha & O’Malley 1999). Chronic alcohol drinking, in addition, results in elevated anxiety and dysregulated responses to stressors. Together, these feed forward interactions enhance motivation for alcohol and are common causes of relapse (Koob 2009; Breese et al. 2011).

One way that stress and alcohol contribute to AUDs is by weakening cognitive control functions that normally aid in restraint from alcohol seeking. Both chronic stress and chronic alcohol induce significant disruptions in cognitive functions such as learning and memory, attention, and executive functions such as planning, response inhibition, and behavioral flexibility (Arnsten 2009; Bernardin et al. 2014; Abernathy et al. 2010). When combined, chronic alcohol use and stress potentially heighten cognitive disruptions that may underlie poor decision making and behavioral control in AUDs (Seo et al. 2014). In particular, stress- and alcohol-induced disruptions in cognitive function impair control over drinking behavior and the ability to adopt alternate mechanisms for coping with stress/anxiety. In the absence of cognitive control mechanisms needed to respond to stressors, individuals with AUDs may instead turn to drinking, thus promoting further problematic use.

Behavioral flexibility is a core executive function of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), measured through set shifting tasks, that is susceptible to impairment from both chronic stress and alcohol exposure (Butts et al. 2013; Liston et al. 2006; Kroener et al. 2012; Badanich et al. 2016). Behavioral flexibility is also highly influenced by ascending modulatory inputs to PFC, including the noradrenergic locus coeruleus (LC) (McGaughy et al. 2008). Behavioral flexibility and adaptive behavior are essential for controlling excessive alcohol intake. Alcohol recovery programs and other behaviors necessary for avoiding alcohol use require learning new, contextually appropriate information as part of adaptive behavioral strategies.

Although the effects of alcohol and stress on behavioral flexibility and other cognitive functions have been measured independently, the cognitive consequences of interactions between the two have not been comprehensively demonstrated. To address this issue we took advantage of a recently developed mouse model of chronic alcohol (ethanol) exposure combined with chronic stress that exacerbates ethanol drinking in dependence (Lopez et al. 2016; Anderson et al. 2016a). In order to determine the impact of a combined chronic ethanol/stress history on cognitive function, we measured contextual learning and behavioral flexibility in mice following exposure to chronic intermittent ethanol (CIE) and/or forced swim stress (FSS). Because both contextual learning and behavioral flexibility are regulated in part by noradrenergic regulation of mPFC, we measured c-Fos activation of mPFC and LC neurons as a rough measure of changes in neuronal activation following CIE and/or FSS (Dragunow & Faull 1989). Our results indicate a profound effect of CIE/FSS on prefrontal-based cognitive function and a disruption in neuronal signaling within both the mPFC and LC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

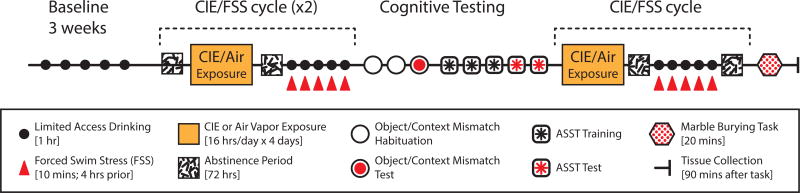

Male C57Bl/6J mice (8 weeks old) purchased from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME) were group-housed (5 per cage) on a reverse 12h light/dark cycle (lights ON at 11:00 PM) with ad libitum access to chow and water, unless otherwise noted. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst in accordance with the guidelines described in the US National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council 2011). An overview of the procedural timeline is illustrated in Fig.1. Briefly, mice were pseudorandomly assigned to four groups with no difference between ethanol consumption during the final week of baseline volitional drinking across groups. Two groups received CIE vapor exposure while the others were air exposure controls. One of the CIE and one of the air exposed groups also received forced swim stress (FSS) prior to daily volitional drinking tests. These treatments generated four exposure groups: Air/no stress (NS) controls, Air/FSS, CIE/NS and CIE/FSS. After two cycles of CIE and FSS we assessed prefrontal dependent cognition in the object/context mismatch and attentional set-shifting task described below. At the end of the of study, animals received an additional cycle of CIE and FSS before brains were collected 90 minutes after exposure to a marble burying test.

Figure 1. Schematic of experimental timeline.

CIE/FSS exposure and testing schedule. Mice underwent three weeks of baseline ethanol drinking before starting weekly cycles of vapor treatment and ethanol test drinking after stress exposure. For all drinking sessions (black circles), mice were given limited access (1h) to a bottle containing 15% ethanol (v/v). After baseline drinking, mice received daily 16h exposure to ethanol or air vapor for 4 consecutive days (orange rectangle) followed by 72h of abstinence (white square with black dashes). After each week of vapor exposure, mice either received daily exposure to a forced swim stressor or were left in their homecage (FSS; red triangle) 4h prior to each limited access drinking session. Cognitive testing was performed after two cycles of CIE and FSS treatment. For the object/context mismatch task, mice underwent 2d of habituation (open circles) before testing 72 hours after drinking (red circles). Mice then started 3d of ASST training (square with black asterisk) followed by 2d of testing (square with red asterisk). Animals were given another cycle of vapor treatment and stress exposure/limited access drinking session. After 72 hours of abstinence from the last drinking session, mice underwent a 20 min marble burying task to measure anxiety. Animals were perfused and brains were collected 90 minutes after completion of marble burying task.

Ethanol Drinking

Mice were placed in individual drinking cages at least 30m prior to 1-hour, 1 bottle ethanol access (15%, v/v) beginning 3h after onset of the dark cycle (Anderson et al. 2016a). Baseline drinking continued until stable levels were established (3 weeks) prior to beginning ethanol vapor. Bottles were weighed before and after drinking sessions. Drip estimates from an ethanol bottle in an empty cage were subtracted from the total volume consumed by each animal. Mice were weighed weekly and ethanol consumption was converted to g/kg. Mice underwent five days of stress exposure followed by volitional drinking beginning 72 hours after each cycle of chronic intermittent ethanol (CIE). Data were analyzed using average consumption of each drinking week.

CIE Protocol

After initial acclimation and baseline drinking, mice (n=38) underwent biweekly intermittent ethanol (n=18) or air-control (n=20) vapor exposure as previously described (Griffin et al. 2009). Each cycle of vapor exposure, mice (5 per cage) mice were placed in Plexiglass inhalation chambers for 16 hours a day for 4 consecutive days. Immediately prior to chamber exposure, ethanol-treated mice received a loading dose of ethanol (1.6 g/kg; IP) and the alcohol dehydrogenase inhibitor pyrazole (1 mmol/kg) at a final volume of 20 ml/kg. Air-treated mice were injected with pyrazole (1 mmol/kg) in saline to control for injection stress. Chamber ethanol levels were monitored daily and maintained at levels that produced blood ethanol concentrations (BECs) within the intoxicating range 180–250 mg/dL. An alcohol oxidase colorimetric assay was used to measure BEC in tail blood samples collected from ethanol-treated mice (Pava et al. 2012; Griffin et al. 2009).

Forced-Swim Stress Exposure

Between cycles of CIE exposure, half of the ethanol-treated and air-control mice (n=10 per group) received daily forced-swim stress (FSS) exposure (Fig. 1), 4 hours before ethanol drinking sessions (Lopez et al. 2016; Anderson et al. 2016a). Mice were gently placed in 4L glass beakers (16 × 25.5 cm) containing 2.5L of fresh tap water (23–25°C) for 10 minutes. Upon removal, mice were dried and placed under heat lamps for 10 minutes before returning to their home cage. Water was changed between mice and dividers were used to visually isolate mice from each other during FSS.

Contextual learning - object/context mismatch

All mice (n=38; 8–10 per treatment group) were tested in a prefrontal dependent object in context task designed to assess contextual learning (Spanswick & Dyck 2012; Barker et al. 2007; Place et al. 2016). Twenty-four hours after the last FSS/drinking session (see Fig. 1) mice were habituated to two different environments in separate rooms (context A and context B, 10 mins per context), one immediately after the other, for two consecutive days. Context A was a transparent rectangular container (42 × 28 × 29 cm) illuminated at 4 lux whereas context B was an opaque green container (36 × 28 × 23 cm) at 25 lux. On test day, mice were given 5 minutes to explore pairs of identical objects in each context (e.g., two PVC pipes in context A, immediately followed by two Legos toys in context B), objects were randomized between contexts and thoroughly cleaned between subjects. After exploring the objects in each context, mice returned to their holding cages for 5 minutes prior to a 3-minute object/context mismatch test. For the test, mice were placed in one context (A or B) containing a pair of objects. One object was previously seen in the same context, and while the other object was seen in the alternate context (e.g., PVC pipe and Lego in context A). Studies using this test show that healthy controls will spend more time interacting with the object from the mismatched context (Spanswick & Dyck 2012). Object test pairings were screened for preference in a separate cohort of naive animals (n=10), and all training and test conditions were counterbalanced for context, order, object pairings, and preference. All trials were digitally recorded and manually scored by an experimenter blinded to the treatment groups. Mice were considered to be interacting with the object if they were facing the object from less than 3 cm away. Climbing the object was not considered as an interaction.

Attentional Set-Shifting Task

Following object/context testing, mice were tested for behavioral flexibility using a two-dimensional (texture and odor) attentional set-shifting task (ASST) similar to previous studies (Birrell & Brown 2000; Young et al. 2010), 6–10 days after their last drinking session (n=20; 5 per treatment group). The ASST apparatus consisted of a custom made acrylic box (49 × 20 × 21 cm) with a removable divider separating the waiting arena from two equal sized choice compartments in the rear of the box. Animals were trained to dig for chocolate sucrose pellets (5 mg; TestDiet, Richmond, IN) in porcelain pots filled with scented digging media (5.5 × 5.5 × 3 cm) atop textured platform (10 × 7.5 × 2.5 cm) in the choice compartments. Crushed sucrose pellets were mixed into all scented digging media to mask the reward odor. Media were refilled on each trial, and pots were replaced after each stage and thoroughly cleaned after use. Each pot was designated to a specific odor to avoid cross-contamination of odor stimuli. Separate platforms of each texture were used for each mouse to avoid introducing scents from unfamiliar mice. Twenty-four hours prior to and during ASST mice were restricted to 2hr daily access to wet food.

Animals were habituated to digging pots and reward pellets in their home cage before ASST training and testing. During training, animals explored the waiting arena and the empty choice compartments for 10 minutes. After returning mice to the waiting arena, an untextured platform and baited digging pot was placed in each choice compartment. All mice learned to dig in the baited bowls. Once mice were able to reliably retrieve the reward pellets in this condition, they were exposed to compound stimulus pairs until all animals had been exposed to each texture and odor and showed digging behavior in each stimulus pair. All stimuli were tested for preference with a separate naive cohort (n=10) so that pairings were similar in salience. Texture pairs included fine sandpaper/burlap, coarse sandpaper/tinfoil, and silk/velvet. Odor pairs included sage/cloves, cinnamon/thyme, and basil/cumin (Table 2A).

Table 2. ASST Task Parameters.

(A) Exemplar pairs of odor and texture stimuli. Odors and textures were matched for salience using a separate cohort of naïve animals (n=10). (B) Example ASST paradigm for an odor to texture shift. ASST stage, relevant dimension and exemplar stimuli are given for each discrimination, rewarded choices highlighted in bold.

| A | |

|---|---|

| Odor Pairs | Texture Pairs |

| Basil & Cumin | Tinfoil & Coarse Sandpaper |

| Cloves & Sage | Velvet & Silk |

| Thyme & Cinnamon | Burlap & Fine Sandpaper |

| B | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Task | Dimension | Combinations | ||

| Relevant | Irrelevant | Correct | Incorrect | |

| SD | Odor | Texture | Cloves | Sage |

| CD | Odor | Texture | Cloves & Velvet | Sage & Silk |

| Cloves & Silk | Sage & Velvet | |||

| CDR | Odor | Texture | Sage & Velvet | Cloves & Silk |

| Sage & Silk | Cloves & Velvet | |||

| ID | Odor | Texture | Basil & Tinfoil | Cumin & Coarse Sandpaper |

| Basil & Coarse Sandpaper | Cumin & Tinfoil | |||

| IDR | Odor | Texture | Cumin & Tinfoil | Basil & Coarse Sandpaper |

| Cumin & Coarse Sandpaper | Basil & Tinfoil | |||

| ED | Texture | Odor | Burlap & Cinnamon | Fine Sandpaper & Thyme |

| Burlap & Thyme | Fine Sandpaper & Cinnamon | |||

Each testing stage began with four discovery trials in which the animal could explore and dig in both choice compartments until they found the reward (McAlonan & Brown 2003). Discovery trials were excluded from analysis. On test trials, the divider was closed and the response recorded when the animal approached the first digging pot. The divider prevented animals from entering more than one compartment per trial. We performed a six stage ASST consisting of simple discrimination (SD), compound discrimination (CD), compound discrimination reversal (CDR), intradimensional discrimination (ID), intradimensional discrimination reversal (IDR), and then extradimensional discrimination (ED; (Table 2B modified from McAlonan & Brown 2003). Testing took place over two days to prevent reward satiation with SD-CDR on Day 1 and ID-ED on Day 2.

If any animal could not meet criterion during the SD or CD stage, they were removed from the task due to an inability to form an attentional set (n=1 CIE/FSS group). Choices were recorded as correct, incorrect, or omissions (no choice after 60s). Criterion was 6/8 correct choices, while failure to complete a stage was 20 omissions or 60 max trials. The rewarded choice compartment and exemplar pairing were randomized so that it was counterbalanced by side. Relevant stimulus dimension was balanced between animals and within groups (e.g. odor to texture). Performance was measured by number of trials completed at each stage and number of errors made. In all groups more trials were needed to complete ED than ID, validating the formation of an attentional set.

Marble burying

After cognitive testing was complete we investigated the effects of CIE and FSS on the development of anxiety-like behavior using a marble burying task (Pleil et al. 2015; Rose et al. 2015). Mice underwent an additional cycle of CIE/FSS and were tested for marble burying 3–5 days after their last drinking session (Fig. 1). Mice (n=38; 8–10 per group) were habituated for two hours to a polycarbonate cage with ~4cm of Sani-Chip bedding (P.J. Murphy, Montville, NJ). Mice were briefly placed in a holding cage while 20 evenly spaced black marbles (9/16”; Moon Marble Company, Bonner Springs, KS) were placed on top of the bedding. Mice were returned to the cage with marbles for the 30m test session, after which the number of marbles buried more than 75% were counted. Data from mice that failed to explore the arena during habituation or froze during the test session were not used (n=2 Air/FSS; n=1 CIE/NS; n=2 CIE/FSS). A clean cage was used for each mouse and the marbles were thoroughly cleaned between subjects.

c-Fos immunohistochemistry

Mice were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) 90 minutes after marble burying. Brains were postfixed in 4% PFA overnight and cryoprotected in 20% sucrose-azide prior to sectioning at 30 µm (Leica CM3050S, Germany). Tissue slices containing mPFC (prelimbic, PL; and infralimbic, IL) and LC were processed with 3–3’ diaminobenzidine and nickel ammonium sulfate substrate (DAB-Ni) for c-Fos reactivity. Tissue was rinsed, quenched in 1% hydrogen peroxide for 10 minutes, and blocked for 1 hour in 3% normal donkey serum before overnight incubation at 4°C with an anti c-Fos rabbit polyclonal antibody (1:15,000; lot no. 2672548; Millipore Corp. Bedford, MA). After rinsing, tissue was incubated at room temp for 2.5h with a biotinylated donkey anti-rabbit secondary (1:500; lot no. 122849; Jackson IR. West Grove, PA). Tissue was rinsed and incubated in avidin-biotin complex (1:500; ABC Vectastain, Burlingame, CA) before chromogenic reaction with DAB-Ni (0.2mg/ml DAB and 6 mg/ml Nickel ammonium sulfate; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Sections were mounted onto Superfrost plus slides (Fisher Scientific) and dried overnight. After dehydration and defatting in ethanol and xylene, slides were coverslipped with DPX mounting medium (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). Histological images for c-Fos quantification were acquired at 10× magnification on an AxioImager M2 microscope (Zeiss, Germany) using StereoInvestigator 11.0 software (MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT).

Data Analyses

Number of c-Fos positive cells was quantified on FIJI software (Schindelin et al. 2012) by an experimenter blinded to treatment. Stereotaxic coordinates for counting c-Fos expression in the target regions included an average count from the following ranges based on Paxinos and Franklin (2008): prelimbic (A/P +2.1 to +1.8; 3–4 sections per animal), infralimbic, (A/P +2.0 to +1.55; n = 2–3 sections per animal) and LC (A/P −5.34 to −5.68; n = 7–8 sections per animal).

For all analyses, p < 0.05 was used as the acceptable α level. Specific statistical comparisons are listed within the results. Where appropriate Grubbs test was used to remove significant outliers. Drinking results were analyzed using SPSS V.24.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) and all other parametric or nonparametric statistical analyses were performed on GraphPad Prism Version 6.00 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). All graphs were composed using GraphPad Prism and figures were compiled in Adobe Illustrator CC (2015).

RESULTS

Drinking

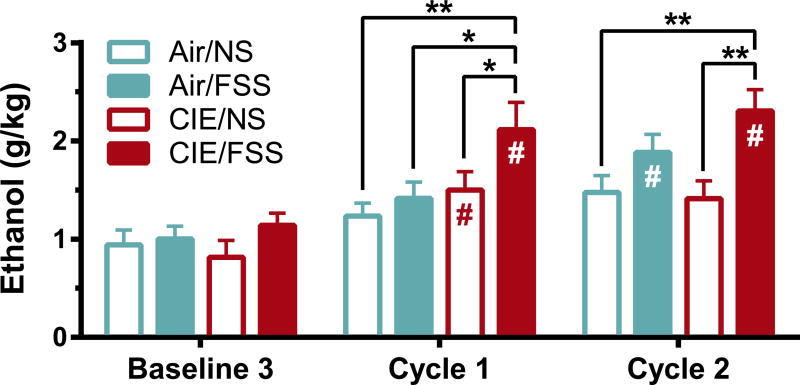

All mice showed similar ethanol consumption during baseline drinking consistent with drinking behavior seen in C57BL/6J mice with this paradigm (Rhodes et al. 2005; Becker & Lopez 2004). Mice were assigned to one of the four treatment groups (Air/NS, Air/FSS, CIE/NS, or CIE/FSS) counterbalanced by ethanol consumption during the final week of baseline drinking. A post-hoc comparison of ethanol consumption between treatments confirmed there were no group differences in baseline drinking [F(3, 203.56) = 0.45, p = 0.72; Fig. 2]. During CIE average BEC intoxication (mg/dL) after vapor chambers did not significantly differ between CIE/NS and CIE/FSS in either cycle [F(1,31) = 1.6, p = 0.21 two-way ANOVA; Table 1].

Figure 2. Stress exacerbates drinking in dependent animals.

Average weekly consumption of ethanol (g/kg) during 1h access to ethanol (15%; v/v) from last baseline and following cycles of ethanol and stress exposure. CIE/FSS mice showed a faster escalation in ethanol consumption that remained significantly greater than Air/NS and CIE/NS mice after both cycles. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. # Indicates a significant difference from baseline (p < 0.05); * indicates significant difference from other treatment groups (p < 0.05).

Table 1. Blood ethanol concentration.

(BEC; mg/dL) from CIE/NS (n=8) and CIE/FSS (n=10) sampled immediately following ethanol-vapor exposure. BEC did not differ between groups of ethanol-treated mice for both cycles of CIE/FSS exposure. Values are shown as mean ± SEM.

| Treatment Group | Cycle 1 | Cycle 2 |

|---|---|---|

| CIE/NS | 198.53 ± 30.56 | 231.97 ± 11.36 |

| CIE/FSS | 241.95 ± 21.76 | 250.81 ± 18.87 |

Analysis of the influence of CIE/FSS on ethanol consumption revealed a main effect of treatment [Fig. 2: F(3, 117.32) = 8.8, p < 0.001] and cycle week [F(4, 258.14) = 64, p < 0.001; repeated measures ANOVA]. Relative to their own baseline levels, both CIE groups increased volitional consumption after the first CIE cycle (CIE/NS, p < 0.05; CIE/FSS, p < 0.001; Bonferroni). However, CIE/FSS mice also drank significantly more ethanol than all other treatment groups (Air/FSS, p < 0.01; Air/NS, p < 0.001; CIE/NS, p < 0.05). Following the second cycle CIE/FSS mice continued to consume significantly more than baseline (p < 0.001). After two cycles, ethanol consumption in CIE/FSS mice was greater than Air/NS (p < 0.001) and CIE/NS (p < 0.001), but not Air/FSS (p = 0.22) highlighting that a combination of both CIE and FSS led to a significant and rapid escalation of volitional drinking. These results are in accordance with previous studies showing that FSS exacerbates drinking in CIE-treated animals (Anderson et al. 2016a; Lopez et al. 2016; Anderson et al. 2016b).

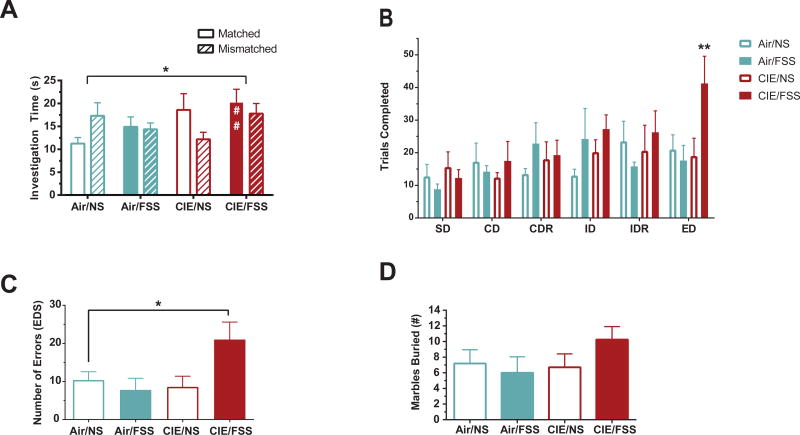

Cognitive function: Contextual learning task

To investigate changes in cognitive function associated with rapid escalation of ethanol drinking, we assessed contextual learning and behavioral flexibility after two cycles of CIE and FSS treatment. For contextual learning, we used an mPFC-dependent object/context mismatch task that measures the formation of object memories within specific contextual environments (“where” memory; Spanswick & Dyck 2012). All groups spent equal time exploring both object/context pairings during the learning phase of the task [F(3,33) = 0.56, p = 0.65; one-way ANOVA]. The order in which the object/contexts were presented did not produce any confounds impact on the test (‘when’ memory) [F(1,29) = 0.0005; p = 0.98; one-way ANOVA]. During the testing phase, Air/NS animals spent more time exploring the object in the mismatched context than the congruent object, as expected (Fig. 3A). Exposure to CIE, FSS, or both impaired performance on this task [main effect of treatment, F(3,60) = 2.9, p < 0.05; two-way ANOVA]. Post hoc analysis revealed that the CIE/FSS group alone spent significantly more time investigating the congruent object/context (p = 0.01 vs Air/NS; Dunnett's), suggesting that CIE/FSS exposure impaired these animals’ ability to integrate or recall object/context information.

Figure 3. Ethanol and stress interactions lead to impairments in cognitive function.

(A) Amount of time spent investigating matched vs. non-matched objects during an object/context mismatch task in mice tested after 2 cycles of vapor/stress treatment. Air/NS animals spent more time exploring the object in the mismatched context than the congruent object, as expected. All treatments disrupted object/context task performance (* p < 0.05). Mice treated with CIE/FSS were selectively impaired on recognizing the previously matched object (## p < 0.01). (B) Number of trials completed per stage (not including omissions) in mice tested in an attentional-set shifting task (ASST) following two cycles of ethanol and stress. CIE/FSS mice completed significantly more trials before reaching criterion during the extra-dimensional (ED) stage than all other groups. (C) Average number of errors made during the ED stage of the ASST. CIE/FSS mice made more errors than Air/NS mice during the ED stage. (D) Number of marbles buried tested 48h after completion of 3 cycles of ethanol and stress. No significant increase was seen in the number of marbles buried after CIE/FSS. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. * indicates significant effect of treatment (p < 0.05); ** indicates significant effect of treatment (p < 0.01).

Cognitive function: ASST

We measured behavioral flexibility using a six-stage ASST. Training began 4–5 days after and testing was performed 6–9 days after the end of the second CIE/FSS cycle (Fig. 1). There was an overall effect of stage on the number of trials completed [F(5,70) = 3.1, p < 0.05, two-way ANOVA]. Post hoc comparisons confirmed that CIE/FSS treated mice required more trials during the ED stage than all other groups (p < 0.05; Dunnett's MCT; Fig. 3B). There were no significant differences across groups for other discriminations (SD, CD, CDR, ID, IDR). Within the ED stage we compared the number of errors and found a significant difference across groups [F(3,15) = 3.4, p < 0.05; one-way ANOVA; Fig. 3C]. Specifically, there was an increase in errors made by CIE/FSS relative to all other groups (p < 0.05; Holm-Sidak’s MCT). There was no difference in omission rates across groups [F (3, 14) = 2.0, p = 0.17; two-way ANOVA], but one subject in the Air/FSS reached the upper limit of 20 omissions during the ED stage. In the CIE/FSS group one subject failed to reverse after a successful ID, and two subjects reached the max number of trials in ED without meeting criterion. Overall, at later stages in the task, the effect of increasing cognitive load became apparent selectively in the CIE/FSS group. These results show that a short duration of exposure to CIE and FSS disrupts behavioral flexibility and attentional control.

Marble burying

Increases in marble burying behavior have been demonstrated during ethanol withdrawal after four or more cycles of CIE (Pleil et al. 2015; Rose et al. 2015), indicating ethanol-induced increases in anxiety and stress-reactivity. Once cognitive testing was complete, mice received an additional CIE/FSS cycle before a marble burying test 3–5 days after last ethanol access (Fig. 1). Although the CIE/FSS group appeared to bury more marbles on average, there were no significant differences in marble burying across groups [KW = (4,29 = 5.5; p = 0.14; Kruskal-Wallis Fig. 3D]. These results indicate that the development of anxiety-like behavior may show a different time course after CIE/FSS exposure than disruptions in cognitive dysfunction.

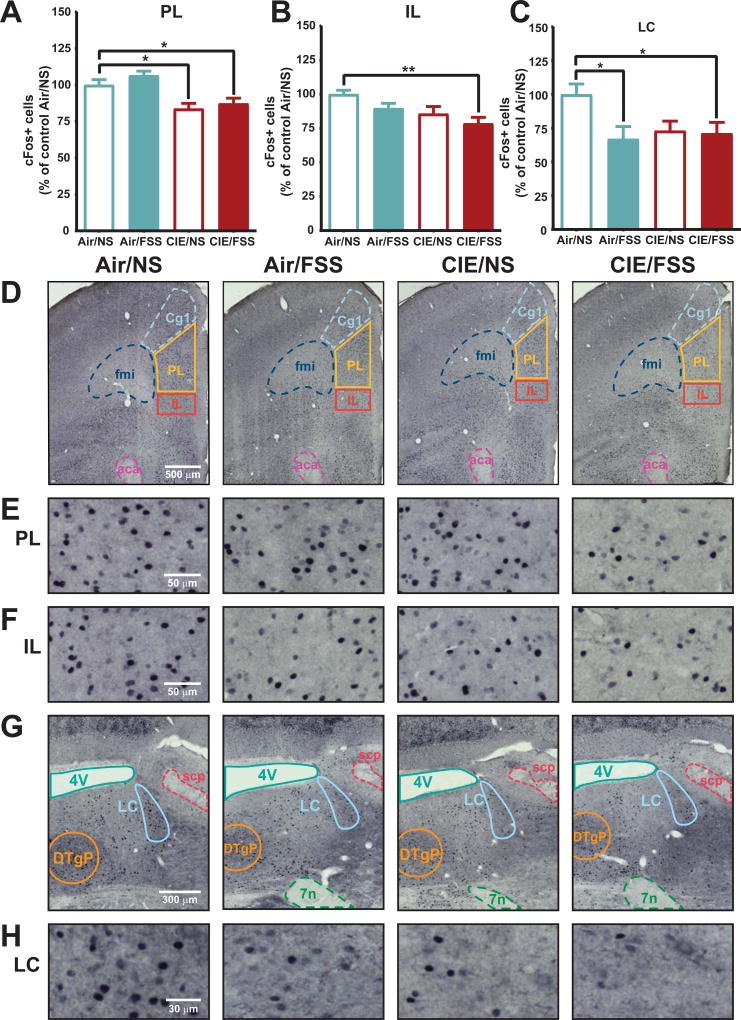

c-Fos

Although we did not detect overt changes in anxiety-like behavior with marble burying, we used the novel context of the task to elicit c-Fos expression related to ethanol and stress history. We assessed c-Fos activity in the mPFC and LC. mPFC is critical for cognitive functions (Dalley et al., 2004; Euston et al. 2012), and LC is a stress-sensitive neuromodulatory input to mPFC that is known to regulate behavioral flexibility (McGaughy et al. 2008). We observed high levels of c-Fos labeling in tissue collected from all mice after marble burying and quantified expression in the prelimbic (PL) and infralimbic (IL) regions of mPFC and LC (Figure 4). In the mPFC, ethanol and stress exposure altered c-Fos activity between groups in PL [F (3, 25) = 8.5, p < 0.001, one-way ANOVA; Fig. 4A], and IL cortex [F (3, 29) = 4.4, p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA; Figure 4B]. Expression in PL cortex was reduced in both CIE/NS (p < 0.05; Dunnett’s), and CIE/FSS (p < 0.05) groups relative to Air/NS controls (1228 ± 45 cells/mm2). Within IL cortex a significant decrease in c-Fos was only observed in CIE/FSS mice (p < 0.01 vs. Air/NS; Dunnett's) relative to Air/NS (1056 ± 30 cells/mm2). Together these findings show that a limited history of CIE exposure impacts PL function, with interactions between CIE and FSS additionally disrupting function in IL. LC also showed a main treatment effect [F (3, 31) = 3.9, p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA; Figure 4C] whereby stress-treated groups showed ~30% reduced c-Fos activation (Air/FSS, p < 0.05; CIE/FSS, p < 0.05; Dunnett’s) relative to Air/NS controls (729± 56 cells/mm2). CIE alone appeared to decrease c-Fos in the LC but this was not statistically significant. As such, limited cycles of CIE or FSS alone altered c-Fos activity in mPFC or LC, respectively. The combination of CIE and FSS led to reductions in c-Fos activity across mPFC and in LC, disrupting cognitive networks at multiple targets.

Figure 4. Ethanol and stress interactions disrupt neuronal function across cognitive networks.

CIE/FSS decreases c-Fos expression in prelimbic PFC (PL, A), infralimbic PFC (IL, B), and locus coeruleus (LC, C) relative to Air/NS. Within the mPFC (D), c-Fos expression in PL (E) was reduced in both CIE treatment groups. CIE/FSS treated animals had more widespread mPFC disruption with additional reductions in IL c-Fos (F). In locus coeruleus (LC) (G), FSS treatment significantly decreased expression in both air- and ethanol-treated mice (H). Values are shown as mean ± SEM. * indicates significant effect of treatment (p < 0.05), ** indicates significant effect of treatment (p < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated that stress and alcohol exposure leads to the rapid development of cognitive dysfunction in dependent subjects. We used a rodent model of repeated forced swim stress and ethanol exposure shown to exacerbate volitional drinking in dependent animals. Two cycles of ethanol and stress produced impairments in mPFC dependent contextual learning and behavioral flexibility. Using c-Fos immunohistochemistry we saw reductions in PL activity in CIE exposed animals, combined with additional reductions in IL of CIE/FSS animals. Stress and ethanol-exposed groups, and to a lesser degree ethanol alone, showed disruptions of neural signaling in the LC, an important ascending neuromodulatory input to mPFC that is known to regulate behavioral flexibility (McGaughy et al. 2008; Zitnik et al. 2016). The disruption in function across neural circuits after CIE/FSS may contribute to the rapid development of cognitive deficits. Further understanding of the impact of ethanol and stress exposure on cognitive networks may elucidate novel therapeutic strategies for regulating excessive drinking and maintaining abstinence.

We saw a rapid acceleration of volitional drinking in CIE/FSS exposed subjects consistent with previous findings characterizing drinking behavior in this model that show escalation of drinking in CIE/FSS subjects above that of CIE alone (Anderson et al. 2016a; Lopez et al. 2016; Anderson et al. 2016b). Our findings provide further evidence for a role of stress in the development of excessive drinking (Becker et al. 2011; Koob 2009). In addition to the acceleration in drinking behavior, our results provide novel evidence for comorbid cognitive dysfunction in this model. We investigated two domains of cognition: contextual learning and behavioral flexibility.

Contextual learning was sensitive to CIE and FSS exposure. Despite comparable exploration during the learning phase, CIE/FSS mice spent significantly more time with the congruent object in the test phase than Air/NS mice, indicating they failed to integrate or recall the original object/context pairings. Mice that received only the ethanol or stress treatment (CIE/NS and Air/FSS, respectively) did not perform significantly differently than Air/NS controls but showed reduced discrimination of object/context pairings. These findings highlight the sensitivity of contextual learning paradigms, and shows that ethanol and stress may exacerbate disruptions in processing contextual information.

Previous studies have shown that object/context learning relies on coordinated information exchange between mPFC and hippocampus (Place et al. 2016). We saw no impact of treatment on hippocampal dependent components of the task such as order (“when” memory) of object/context presentation (Ennaceur et al. 2005; Barker et al. 2007), arguing that the deficits we saw in contextual learning may be primarily driven by disruption of mPFC function.

Further evidence for mPFC dysfunction after CIE/FSS came from investigating behavioral flexibility using the ASST. Set-shifting ability is a well-recognized PFC-dependent behavior that can be assessed in both preclinical models and humans (Brown & Tait 2016). Set shifting ability is impaired in heavy drinkers without an AUD, as well as people with AUDs who have had multiple relapses (Houston et al. 2014; Trick et al. 2014). Our data demonstrate that limited exposure to CIE and FSS in mice can generate impairments in behavioral flexibility. The deficits were specific to extradimensional shifting and not in less cognitively demanding discriminations needed to form, shift or reverse an attentional set within a given dimension (SD/CD, ID and CDR/IDR respectively). The impairments (increased trials and errors) were specific to the combined CIE/FSS exposure with no significant changes in animals that were exposed to either CIE or FSS alone.

Exposure to stress (Bondi et al. 2008; Liston et al. 2006) or alcohol (Kroener et al. 2012; Gass et al. 2014) can elicit deficits behavioral flexibility, although evidence is mixed (Badanich et al. 2011). We did not see this phenotype develop in either CIE or FSS alone subjects the current study. Our paradigm used limited ethanol exposure (two cycles) before cognitive testing, which may be why no overt deficits were found in the CIE alone group. Similarly, stress type, duration, and intensity can have profound impact on cognitive and drinking outcomes (Hurtubise & Howland 2016; Lopez et al. 2016). Although the CIE and FSS paradigms alone did not trigger cognitive impairments, the interactions between ethanol and stress that triggered excessive drinking also accelerated the development of cognitive dysfunction.

Previous studies have also seen changes in anxiety-like behavior including marble burying during acute withdrawal after CIE (Pleil et al. 2015; Rose et al. 2015). Although stress and ethanol accelerated the development of cognitive dysfunction we did not see a significant change in marble burying across any groups, despite a slight trend for greater anxiety-like behavior in the CIE/FSS mice. Differences between our findings and that of other groups are likely due to the limited cycles of CIE/FSS exposure in the current study and/or differences in amount of time between final vapor exposure and testing.

Identifying the neural circuits susceptible to ethanol and stress interactions may lead to novel therapeutic targets that regulate behavioral control over drinking behaviors and stress related drinking. Given the specific cognitive dysfunction we saw in both contextual learning and behavioral flexibility we chose to measure c-Fos activation in two candidate regions; mPFC and LC (Dragunow & Faull 1989). Intact mPFC functioning is critical for both contextual learning and behavioral flexibility (Liston et al. 2006; Floresco et al. 2008; Birrell & Brown 2000). mPFC function in the ASST is also dependent on ascending LC-norephinephrine (NE) input, with impairments in LC-NE signaling selectively disrupting the ED component (Tait et al. 2007; McGaughy et al. 2008; Janitzky et al. 2015).

We saw high levels of c-Fos activity in all subjects with key differences between treatment groups. Repeated cycles of CIE, FSS or CIE/FSS disrupted c-Fos activity in multiple regions: CIE or FSS exposure decreased c-Fos activity in dorsal mPFC (PL) and LC, respectively, and CIE/FSS treated mice showed reduced c-Fos activity in both of these regions. In addition, CIE/FSS exposure disrupted c-Fos within the ventral mPFC (IL). Together, these results provide evidence of an additive disruption across cognitive circuits caused by ethanol and stress exposure, with further vulnerabilities triggered by the interactions between ethanol and stress. Future investigation is needed to understand how changes in c-Fos reflect neuronal function in cognitive circuits after ethanol and stress exposure and whether and how interactions across systems are disrupted following chronic stress and alcohol.

The current study investigated contextual learning, behavioral flexibility and c-Fos activity after CIE and FSS exposure in male mice to characterize the cognitive phenotype of a newly developed model of ethanol and stress interactions. However, there is ample evidence of sexually dimorphic responses to ethanol and stress, including sex-selective changes in LC structure and function (Valentino et al. 2012; Retson et al. 2015; Retson et al. 2016). Additional studies are needed to probe sex-specific changes in cognition and neural function associated with ethanol and stress interaction, as demonstrated in males here. Investigating neural systems altered in appropriate preclinical models that reproduce the multifaceted interactions of ethanol and stress comorbidities will increase the likelihood of identifying novel therapeutic targets to treat alcohol use disorders and restore cognitive control over drinking behavior.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health awards, R21AA024571 (DEM), and U01AA025481 (EMV/DEM). The authors would like to thank Michael Kelberman for assistance with behavioral quantification and Dr. Jared Young for assistance in designing the ASST.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

References

- Abernathy K, Chandler LJ, Woodward JJ. Alcohol and the prefrontal cortex. International Review of Neurobiology. 2010;91:289–320. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(10)91009-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RI, Lopez MF, Becker HC. Forced swim stress increases ethanol consumption in C57BL/6J mice with a history of chronic intermittent ethanol exposure. Psychopharmacology, (Berl) 2016a;233:2035–2043. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4257-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson RI, Lopez MF, Becker HC. Stress-Induced Enhancement of Ethanol Intake in C57BL/6J Mice with a History of Chronic Ethanol Exposure: Involvement of Kappa Opioid Receptors. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2016b;10:45. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2016.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnsten AFT. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2009;10:410–422. doi: 10.1038/nrn2648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badanich KA, Fakih ME, Gurina TS, Roy EK, Hoffman JL, Uruena-Agnes AR, Kirstein CL. Reversal learning and experimenter-administered chronic intermittent ethanol exposure in male rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2016;233:3615–26. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4395-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badanich KA, Becker HC, Woodward JJ. Effects of chronic intermittent ethanol exposure on orbitofrontal and medial prefrontal cortex-dependent behaviors in mice. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2011;125:879–891. doi: 10.1037/a0025922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker GR, Bird F, Alexander V, Warburton EC. Recognition Memory for Objects, Place, and Temporal Order: A Disconnection Analysis of the Role of the Medial Prefrontal Cortex and Perirhinal Cortex. Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;27:2948–2957. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5289-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC, Lopez MF. Increased ethanol drinking after repeated chronic ethanol exposure and withdrawal experience in C57BL/6 mice. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2004;28:1829–1838. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000149977.95306.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC, Lopez MF, Doremus-Fitzwater TL. Effects of stress on alcohol drinking: a review of animal studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2011;218:131–156. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2443-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardin F, Maheut-Bosser A, Paille F. Cognitive impairments in alcohol-dependent subjects. Frontiers in Psychiatry / Frontiers Research Foundation. 2014;5:78. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell JM, Brown VJ. Medial frontal cortex mediates perceptual attentional set shifting in the rat. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:4320–4324. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04320.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi CO, Rodriguez G, Gould GG, Frazer A, Morilak DA. Chronic unpredictable stress induces a cognitive deficit and anxiety-like behavior in rats that is prevented by chronic antidepressant drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:320–331. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breese GR, Sinha R, Heilig M. Chronic alcohol neuroadaptation and stress contribute to susceptibility for alcohol craving and relapse. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2011;129:149–171. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown VJ, Tait DS. Attentional Set-Shifting Across Species. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. 2016;28:363–95. doi: 10.1007/7854_2015_5002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butts KA, Floresco SB, Phillips AG. Acute stress impairs set-shifting but not reversal learning. Behavioural Brain Research. 2013;252:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragunow M, Faull R. The use of c-fos as a metabolic marker in neuronal pathway tracing. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 1989;29:261–265. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(89)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennaceur A, Michalikova S, Bradford A, Ahmed S. Detailed analysis of the behavior of Lister and Wistar rats in anxiety, object recognition and object location tasks. Behavioural Brain Research. 2005;159:247–266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floresco SB, Block AE, Tse MTL. Inactivation of the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat impairs strategy set-shifting, but not reversal learning, using a novel, automated procedure. Behavioural Brain Research. 2008;190:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass JT, Glen WB, Jr, Mcgonigal JT, Trantham-Davidson H, Lopez MF, Randall PK, Yaxley R, Floresco SB, Chandler LJ. Adolescent alcohol exposure reduces behavioral flexibility, promotes disinhibition, and increases resistance to extinction of ethanol self-administration in adulthood. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:2570–2583. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WC, 3rd, Lopez MF, Yanke AB, Middaugh LD, Becker HC. Repeated cycles of chronic intermittent ethanol exposure in mice increases voluntary ethanol drinking and ethanol concentrations in the nucleus accumbens. Psychopharmacology. 2009;201:569–580. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1324-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houston RJ, Derrick JL, Leonard KE, Testa M, Quigley BM, Kubiak A. Effects of heavy drinking on executive cognitive functioning in a community sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtubise JL, Howland JG. Effects of stress on behavioral flexibility in rodents. Neuroscience. 2016;345:176–192. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janitzky K, Lippert MT, Engelhorn A, Tegtmeier J, Goldschmidt J, Heinze HJ, Ohl FW. Optogenetic silencing of locus coeruleus activity in mice impairs cognitive flexibility in an attentional set-shifting task. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2015;9:286. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. Brain stress systems in the amygdala and addiction. Brain Research. 2009;1293:61–75. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroener S, Mulholland PJ, New NN, Gass JT, Becker HC, Chandler LJ. Chronic Alcohol Exposure Alters Behavioral and Synaptic Plasticity of the Rodent Prefrontal Cortex. PloS One. 2012;7:e37541. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liston C, Miller MM, Goldwater DS, Radley JJ, Rocher AB, Hof PR, Morrison JH, McEwen BS. Stress-induced alterations in prefrontal cortical dendritic morphology predict selective impairments in perceptual attentional set-shifting. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;26:7870–7874. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1184-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MF, Anderson RI, Becker HC. Effect of different stressors on voluntary ethanol intake in ethanol-dependent and nondependent C57BL/6J mice. Alcohol. 2016;51:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2015.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlonan K, Brown VJ. Orbital prefrontal cortex mediates reversal learning and not attentional set shifting in the rat. Behavioural Brain Research. 2003;146:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaughy J, Ross RS, Eichenbaum H. Noradrenergic, but not cholinergic, deafferentation of prefrontal cortex impairs attentional set-shifting. Neuroscience. 2008;153:63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8. National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pava MJ, Blake EM, Green ST, Mizroch BJ, Mulholland PJ, Woodward JJ. Tolerance to cannabinoid-induced behaviors in mice treated chronically with ethanol. Psychopharmacology. 2012;219:137–147. doi: 10.1007/s00213-011-2387-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Place R, Farovik A, Brockmann M, Eichenbaum H. Bidirectional prefrontal-hippocampal interactions support context-guided memory. Nature Neuroscience. 2016;19:992–994. doi: 10.1038/nn.4327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleil KE, Lowery-Gionta EG, Crowley NA, Li C, Marcinkiewcz CA, Rose JH, Mccall NM, Maldonado-Devincci AM, Morrow AL, Jones SR, Kash TL. Effects of chronic ethanol exposure on neuronal function in the prefrontal cortex and extended amygdala. Neuropharmacology. 2015;99:735–749. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retson TA, Reyes BA, Van Bockstaele EJ. Chronic alcohol exposure differentially affects activation of female locus coeruleus neurons and the subcellular distribution of corticotropin releasing factor receptors. Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2015;56:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retson TA, Sterling RC, Van Bockstaele EJ. Alcohol-induced dysregulation of stress-related circuitry: The search for novel targets and implications for interventions across the sexes. Progress in Neuro-psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 2016;65:252–259. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes JS, Best K, Belknap JK, Finn DA, Crabbe JC. Evaluation of a simple model of ethanol drinking to intoxication in C57BL/6J mice. Physiology & behavior. 2005;84:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JH, Karkhanis AN, Chen R, Gioia D, Lopez MF, Becker HC, Mccool BA, Jones SR. Supersensitive Kappa Opioid Receptors Promotes Ethanol Withdrawal-Related Behaviors and Reduce Dopamine Signaling in the Nucleus Accumbens. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;19:1–10. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyv127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez JY, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nature Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo D, Dongju S, Rajita S. The neurobiology of alcohol craving and relapse. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 2014:355–368. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-62619-6.00021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, O’Malley SS. Craving for alcohol: findings from the clinic and the laboratory. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 1999;34:223–230. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanswick SC, Dyck RH. Object/context specific memory deficits following medial frontal cortex damage in mice. PloS One. 2012;7:e43698. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait DS, Brown VJ, Farovik A, Theobald DE, Dalley JW, Robbins TW. Lesions of the dorsal noradrenergic bundle impair attentional set-shifting in the rat. The European Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;25:3719–3724. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trick L, Kempton MJ, Williams SC, Duka T. Impaired fear recognition and attentional set-shifting is associated with brain structural changes in alcoholic patients. Addiction Biology. 2014;19:1041–1054. doi: 10.1111/adb.12175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Reyes B, Van Bockstaele E, Bangasser D. Molecular and cellular sex differences at the intersection of stress and arousal. Neuropharmacology. 2012;62:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JW, Powell SB, Geyer MA, Jeste DV, Risbrough VB. The mouse attentional-set-shifting task: A method for assaying successful cognitive aging? Cognitive, Affective & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2010;10:243–251. doi: 10.3758/CABN.10.2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitnik GA, Curtis AL, Wood SK, Arner J, Valentino RJ. Adolescent Social Stress Produces an Enduring Activation of the Rat Locus Coeruleus and Alters its Coherence with the Prefrontal Cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:1376–85. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]