Abstract

Objective

To determine the costs associated with delirium in critically ill children.

Design

Prospective observational study.

Setting

An urban, academic, tertiary-care pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) in New York City.

Patients

Four-hundred and sixty-four consecutive PICU admissions between 9/2/2014 and 12/19/2014.

Interventions

None.

Measurements and Main Results

All children were assessed for delirium daily throughout their PICU stay. Hospital costs were analyzed using cost-to-charge ratios, in 2014 dollars. Median total PICU costs were higher in patients with delirium than in patients who were never delirious ($18,832 vs. $4,803, p<0.0001). Costs increased incrementally with number of days spent delirious (median cost of $9,173 for 1 day with delirium, $19,682 for 2–3 days with delirium, and $75,833 for >3 days with delirium, p<0.0001); this remained highly significant even after adjusting for PICU length of stay (p<0.0001). After controlling for age, gender, severity of illness, and PICU length of stay, delirium was associated with an 85% increase in PICU costs (p<0.0001).

Conclusions

Pediatric delirium is associated with a major increase in PICU costs. Further research directed at prevention and treatment of pediatric delirium is essential to improve outcomes in this population, and could lead to substantial healthcare savings.

Keywords: delirium, pediatric, costs, intensive care, critical care, economic analysis

Introduction

Health care costs constitute a substantial portion of the national budget, with recent data indicating that costs related to critical care exceed 80 billion dollars in the United States (US) annually(1). In adults, delirium is associated with a significant increase in hospital costs, with estimates of greater than four billion dollars each year(2). Prior studies demonstrate an attributable cost to hospital acquired complications within pediatrics, including nosocomial and catheter-associated infections and unplanned extubations(3,4). However, to date, there has been no investigation of the contribution of pediatric delirium to pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) costs. We hypothesized that pediatric delirium would independently increase cost of PICU stay.

Delirium occurs as a result of an underlying medical illness, or its treatment. It manifests as an acute and fluctuating change in cognition and attention. Delirium is a prevalent complication of pediatric critical illness, with serious effects on the short- and long-term health of affected children(5–8). Despite this fact, children’s hospitals have been slow to implement delirium screening(9). Similar to adults, it is likely that pediatric delirium contributes substantially to hospital costs. With a better understanding of the true cost of pediatric delirium – including the financial burden on society – there may be added motivation to recognize, treat, and prevent this important problem.

The recent advent of bedside delirium screening tools validated for use in the PICU allow for routine screening (10–12). In this study, our objective was to follow approximately 500 consecutive PICU admissions, prospectively collect data regarding daily delirium status throughout the ICU stay, and determine the attributable cost of PICU delirium.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Weill Cornell Medical Center, at New York Presbyterian Hospital. An initial cohort of patients from 500 consecutive admissions was selected, and cost data generated by the hospital’s finance department. All patients admitted to the PICU and charged for services within the 15-week study period were included. Only patients for whom delirium status was never determined, either because they were comatose throughout their ICU stay, or due to missed opportunities for delirium screening, were excluded.

The subjects of this investigation are part of a larger cohort of children observed over the course of a 12-month period as part of a project to study the natural history of delirium in critically ill children. This study is only one of several planned analyses that will include these children. All data regarding costs that are presented here are novel and have not been published elsewhere.

All children were assessed for delirium once during each 12 hour shift by the bedside nurse as part of routine PICU care, using the Cornell Assessment for Pediatric Delirium (CAPD), a highly reliable observational tool validated in children of all ages, including newborns(10). Children who screened positive for delirium (CAPD score ≥9) had the diagnosis confirmed by the medical team. A PICU stay with at least one day of delirium was considered “ever delirious”.

Data collection

Data collected upon admission to the PICU included demographics, diagnosis, and severity of illness scores, as determined by the Pediatric Index of Mortality II (PIM2)(13). Daily data included delirium status. There were 4 possible assignments each day: 1. Normal mental status (i.e.: delirium-free and coma-free). 2. Delirium (CAPD score ≥9 with diagnosis confirmed by care team). 3. Coma (unarousable to verbal stimulation, thus un-assessable for delirium). 4. Missing status (patient was not assessed for delirium due to lack of compliance with screening protocol).

Delirium duration was assessed by counting the number of days with delirium within a PICU stay. Because of the skewed distribution for number of days with delirium, these were categorized by tertiles (1, 2–3, >3 days).

Cost determination

Costs were calculated after the patient was discharged, by reviewing detailed, ledger-level, billing data by day of hospitalization, as recorded by the hospital’s finance department. Costs were considered “PICU related” if they were incurred on a day when the patient was present in the PICU, after excluding those charges that were incurred prior to ICU admission (i.e.: in the emergency department or operating room). Costs were subdivided into categories based on cost-centers including: nursing, pharmacy, therapy, radiology, and laboratory. Hospital costs were then analyzed using individual cost-center specific cost-to-charge ratios, in 2014 dollars, in order to estimate actual costs. This is an approach used in prior cost-analysis studies, and the method used in the well-designed Milbrandt, et al. study assessing the costs associated with delirium in adults (3,14,15).

Total PICU cost and distribution of costs within subcategories, as described above, were determined for each patient. In addition, daily cost per PICU day was calculated for each patient by dividing the total PICU cost by PICU length of stay (LOS).

Statistical Methods

Descriptive statistics were generated to describe the characteristics of the PICU admissions for categorical and continuous factors. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare non-parametric continuous cost variables. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare total PICU costs and average costs per PICU day between groups. To account for the possible effect of missing days, analyses were repeated assuming that missing patient-days were all without delirium. (This conservative approach was chosen so as to assign all costs for missing days to days without delirium, and avoid the possibility of falsely inflating costs associated with delirium). As results did not materially change, unknown days were excluded for the remainder of analyses. Multivariable linear regression was performed to assess the influence of delirium on total PICU cost, controlling for other covariates identified as possible cost drivers. These included PICU LOS (number of PICU days), age (yr), gender, and probability of mortality (POM as determined by the PIM2 score). Subgroup analysis was performed to include only days spent on invasive mechanical ventilation (MV). Because the total PICU cost data were skewed, costs exceeding $100,000 (n=9) were trimmed at $100,000 and the natural logarithm transformation of all costs was taken before multivariable modeling was performed. Relative costs and 95% confidence intervals were computed by exponentiation of the regression estimates. All statistical tests were two-sided with statistical significance evaluated at the 0.05 alpha level. Analyses were performed with R version 3.2.1 for Windows 64-bit.

Results

Of the initial 500 patients, 28 were not associated with any PICU charges and were excluded. One patient had 2 PICU stays within one hospitalization; these were combined into one PICU stay. Five patients remained comatose throughout their hospitalization; two patients had unknown delirium status during their PICU stay. These seven patients were excluded from analysis. This resulted in 464 distinct PICU admissions. Delirium developed in 74 of the 464 patients, for an incidence of 15.9% in this cohort.

The 464 admissions comprised 2,442 PICU days, with an average LOS of five days. Delirium status had been prospectively established in all but 45 of these patient-days; when missing days were treated as “without delirium” the results were unchanged. Thus 2,397 days were included in daily cost analysis and LOS was adjusted to discount these 45 days. Of the 2,397 patient-days included, 372 were with delirium (15.5%), 167 in coma (7%), and 1,858 patient-days (77.5%) were not associated with either delirium or coma (i.e.: patients had normal mental status).

Table 1 shows patient demographic and clinical characteristics. The largest age group was 2 years or younger (38.8%) and respiratory insufficiency/failure was the most frequently reported admitting diagnosis (52.8%). Median LOS was 3 days, with interquartile range (IQR) of 2–5 days. Of the patients deemed ever delirious (N=74, 15.9%), the median number of days with delirium was 2, with an IQR of 1 to 5.75. Of those who were ever delirious, 33 (44.6%) had only one delirium day; 9 (12.2 %) had more than 10 delirium days.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics (N=464)

| Characteristic | Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 266 (57.3%)

|

| Age (yr) | 0–2 | 180 (38.8%) |

| 2–5 | 93 (20.0%) | |

| 5–13 | 110 (23.7%) | |

| >13 | 81 (17.5%)

|

|

| Diagnosis | Cardiac disease | 34 (7.3%) |

| Hematologic/Oncologic disorder | 4 (0.9%) | |

| Infectious/inflammatory | 47 (10.1%) | |

| Neurologic disorder | 105 (22.6%) | |

| Renal/Metabolic disorder | 29 (6.3%) | |

| Respiratory insufficiency/failure | 245 (52.8%)

|

|

| Probability of Mortality | ≤0.3% | 153 (33.0%) |

| >0.3% & ≤1.3% | 151 (32.5%) | |

| >1.3% | 160 (34.5%)

|

|

| PICU LOS* | 5.17, 3.00 (7.65)

|

|

| Ever Delirious | 74 (15.9%)

|

|

| Number of Delirious Days | 0 | 390 (84.1%) |

| 1 | 33 (7.1%) | |

| 2–3 | 17 (3.7%) | |

| >3 | 24 (5.2%)

|

|

| Ever Coma | 39 (8.4%) |

Description of the 464 admissions to the PICU during the study period.

Probability of Mortality as determined by the PIM2 score.

as Mean, Median (SD)

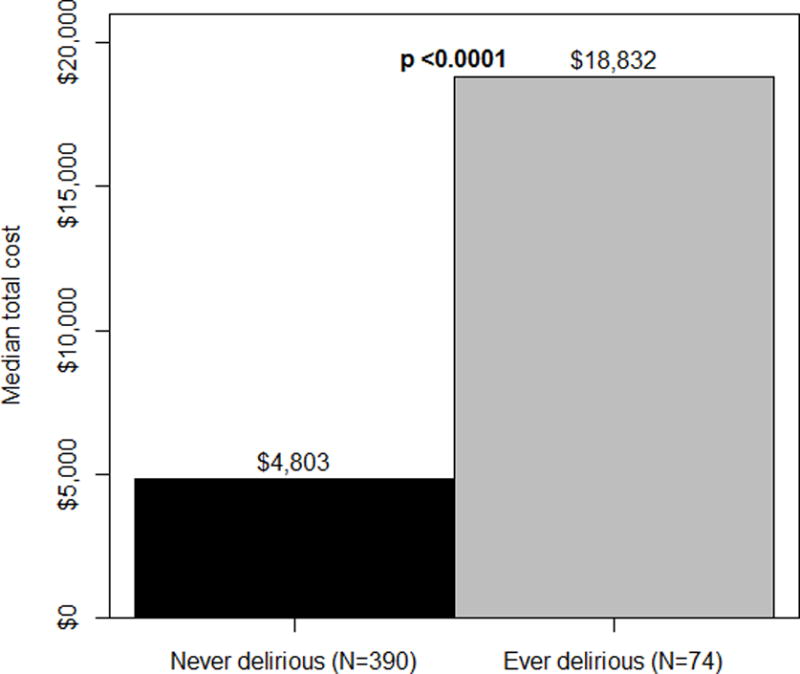

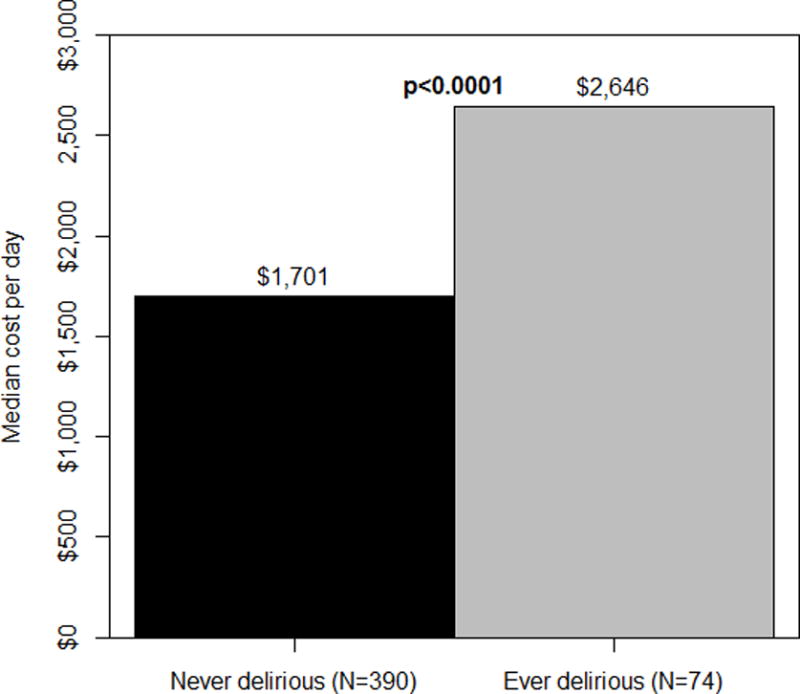

Total costs of PICU care were significantly higher in the ever delirious group compared with the never delirious group (p <0.0001; Figure 1 and Supplemental Digital Content–Table 1). This was expected because of the known association between pediatric delirium and increased length of stay, and is consistent with the adult literature(15,16). However, even after controlling for LOS by comparing costs per PICU day, the median cost per day for patients in the ever delirious group was significantly higher than for those in the never delirious group (p <0.0001; Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Total PICU cost: never vs. ever delirious

Costs of PICU care, reported as median cost in 2014 US dollars, were higher in the ever delirious group (p <0.0001).

Figure 2.

Cost per day: never vs. ever delirious

Costs per day (total PICU cost divided by PICU LOS), reported as median cost in 2014 US dollars, were higher in the ever delirious group (p <0.0001).

Total costs for nursing, labs, pharmacy, therapy, and radiology subcategories were all significantly higher in the ever delirious group compared with the never delirious group (all p <0.0001) (Supplemental Digital Content–Table 1). Daily costs of PICU care were significantly higher for a day with delirium as compared with a day without delirium, with median daily costs of $2,886 and $2,346 respectively (p <0.0001), representing a 23% increase in costs per day. When only days on MV were assessed (n=569), daily costs remained significantly higher for a delirium day, with a median of $3274, versus $2913 for a day on MV without delirium (p=0.003), demonstrating a 12.4% increase in daily cost.

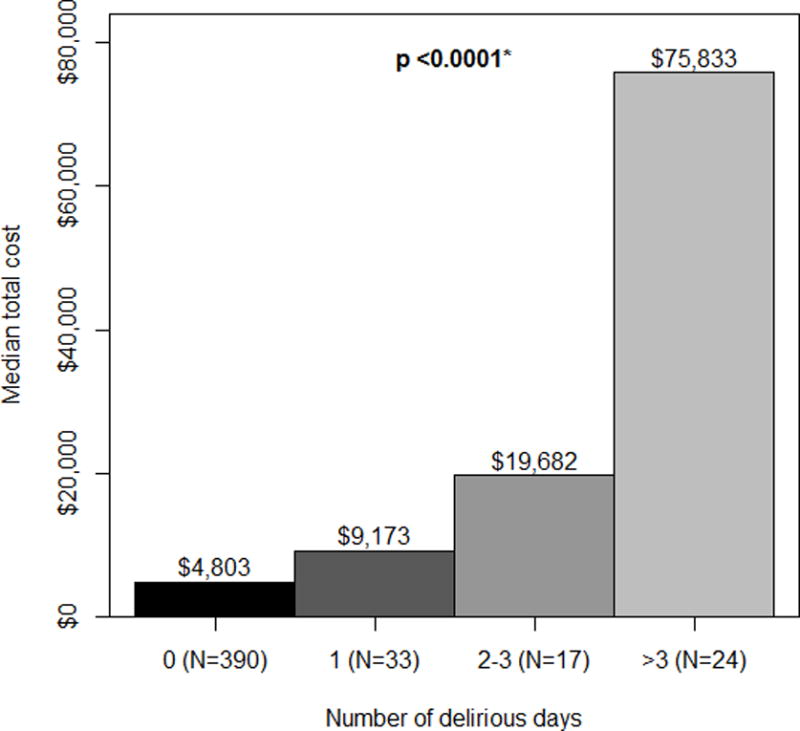

Total costs were significantly different across delirium severity groups (p <0.0001, Figure 3), with a dose-response effect noted. To control for the possible effect of increasing length of stay on this finding, the cost per day was calculated for each patient. As delirium severity increased across groups, median costs per day increased incrementally as well, with $1,701, $2,087, $2,818, and $3,163, for patients with 0, 1, 2–3, and >3 days with delirium, respectively (p<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Total PICU cost by number of days delirious

Total costs, reported as median cost in 2014 US dollars, were significantly different across delirium severity groups (p <0.0001). *P value represents difference between the 4 categories as assessed by the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Multivariable modeling predicting the total costs of PICU care (Table 2), indicated that the costs for the ever delirious patients were 85% greater than the costs for those in the never delirious group, after adjusting for LOS, age, gender, and severity of illness (p <0.0001). Length of stay drove costs as well, with each additional PICU day resulting in an 8% increase in total costs after adjustment (p <0.0001). Patients 2–5 years of age had total costs 18% lower than patients 2 years or younger (p=0.025). Patients with the highest severity of illness (highest PIM2 tertile, with POM higher than 1.3%), had a 26% increase in total costs compared to the group with the lowest severity of illness (p=0.006).

Table 2.

Multivariable Linear Regression Analysis Predicting PICU Costs (N =464)

| Relative Cost (95% CI) | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ever Delirious | 1.85 (1.51–2.26) | <0.0001 | |

| Number of PICU Days | 1.08 (1.07–1.09) | <0.0001 | |

| Age (yr) | 0–2 (ref) | ||

| 2–5 | 0.82 (0.69–0.97) | 0.025 | |

| 5–13 | 1.15 (0.98–1.36) | 0.093 | |

| >13 | 1.06 (0.88–1.28) | 0.522 | |

| Gender | Male | 1.09 (0.96–1.24) | 0.173 |

| Probability of Mortality | ≤0.3% (ref) | ||

| >0.3% & ≤ 1.3% | 1.07 (0.92–1.26) | 0.376 | |

| >1.3% | 1.26 (1.07–1.48) | 0.006 |

Results are from a multivariable linear regression with log-transformed cost as outcome. Predictors include: Ever Delirious, Number of PICU Days, Age (yr), Gender, and Probability of Mortality (as determined by the PIM2 score). Ratios >1.0 for relative costs and their respective 95% confidence intervals indicate increased cost over the reference group.

Discussion

A recent body of pediatric research demonstrates that delirium is a prevalent complication of pediatric critical illness, with identifiable risk factors, and measurable effects on patient outcomes(5,6). A substantial percentage of pediatric delirium is likely preventable, making this an area of avoidable morbidity and expense(17–19).

A diagnosis of delirium is associated with an 85% increase in PICU costs. This is expected when viewed in the context of previous research. For example, development of delirium in children has been associated with severity of the underlying medical illness(24); severity of illness is known to be a cost-driver. In addition, a study in the Netherlands showed that delirium prolonged PICU stay by 2.39 days, independent of severity of illness, age, or admission diagnosis(7). Clearly, increased time spent in the PICU will substantially increase hospital costs. Finally, need for MV is associated with higher PICU costs (25), and delirium likely contributes to this need, with studies in critically ill adults demonstrating an association between delirium diagnosis and increased length of time on MV(2,26).

However, statistical modeling showed that pediatric delirium was independently associated with increased costs, even after controlling for severity of illness and length of stay. When assessed by costs per PICU day, daily costs remained significantly higher in the delirious subjects. When analyzed not by subject but by actual days, patient-days with delirium were more costly than days that were delirium- and coma-free. Subgroup analysis that included only days spent on MV demonstrated a 12% increase in costs on MV days with delirium. Sub-category analyses show that patients with delirium generated more nursing, laboratory, pharmacy, radiology, and therapy charges. This implies that caring for delirious children is resource-intensive, with increased costs generated accordingly. The data also indicate a dose-response relationship between delirium and costs. We do not currently have a way of assigning severity to a child’s delirium; as a surrogate, we used duration of delirium as a marker. With increased exposure to delirium, there is a corresponding increase in hospital costs.

Limitations

This study has several strengths. It includes a large number of patients, and granular data regarding daily delirium status and costs, with costs allocated and analyzed per day incurred. This study also has important limitations. Cost data was generated from a single institution, and may not be widely generalizable. Also, the present study only includes hospital costs, and does not take into account physician charges, or costs attributable to delirium after discharge. This underestimates the true healthcare cost of pediatric delirium. Future studies should take into account physician charges, as delirious children are more likely to be seen by consultants, and spend longer time in the PICU where daily intensivist charges accrue(6,7). Further investigations are needed to account for the after-effects of delirium, where children may be at-risk for long-term consequences after discharge from the hospital that could require costly medical, educational, and vocational interventions(20–23).

Conclusion

It is likely that pediatric delirium contributes an enormous amount to US healthcare costs. In our cohort, the incidence of delirium was 16%, and delirium was associated with an increase in PICU cost of approximately $14,000 per admission. With approximately 250,000 children admitted to critical care units in the US annually, this could translate into more than $560 million each year in hospital charges alone. Further research directed at prevention and treatment of pediatric delirium is essential to improve outcomes in this population, and could lead to substantial reduction in healthcare costs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sarah Walker, Director of NY Presbyterian Children’s Service Line, and the NY Presbyterian Hospital Department of Finance (in particular Mark Nowak and Rob Fursich) for their assistance. The authors would also like to gratefully acknowledge the Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program (ECRIP), whose support made this study possible, and the Clinical Translational Science Center (CTSC), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant #UL1-TR000457-06.

Financial Support:

Financial support for this study was provided by the Empire Clinical Research Investigator Program (ECRIP), and the Clinical Translational Science Center (CTSC), grant #UL1-TR000457-06.

Contributor Information

Chani Traube, Weill Cornell Medical College.

Elizabeth A. Mauer, Weill Cornell Medical College.

Linda M. Gerber, Weill Cornell Medical College.

Savneet Kaur, Weill Cornell Medical College.

Christine Joyce, New York Presbyterian Hospital.

Abigail Kerson, Weill Cornell Medical College.

Charlene Carlo, Weill Cornell Medical College.

Daniel Notterman, Princeton University.

Stefan Worgall, Weill Cornell Medical College.

Gabrielle Silver, Weill Cornell Medical College.

Bruce M. Greenwald, Weill Cornell Medical College.

References

- 1.Chang B, Lorenzo J, Macario A. Examining Health Care Costs. Anesthesiol Clin. 2015 Dec;33(4):753–70. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2015.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, Ely EW, Gélinas C, Dasta JF, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Pain, Agitation, and Delirium in Adult Patients in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Med. 2013 Jan;41(1):278–80. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182783b72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nowak JE, Brilli RJ, Lake MR, Sparling KW, Butcher J, Schulte M, et al. Reducing catheter-associated bloodstream infections in the pediatric intensive care unit: Business case for quality improvement. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine. 2010 Sep;11(5):579–87. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181d90569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roddy DJ, Spaeder MC, Pastor W, Stockwell DC, Klugman D. Unplanned Extubations in Children: Impact on Hospital Cost and Length of Stay. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015 Jul;16(6):572–5. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schieveld JN, Janssen NJ. Delirium in the Pediatric Patient: On the Growing Awareness of Its Clinical Interdisciplinary Importance. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(7):595–6. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silver G, Traube C, Gerber LM, Sun X, Kearney J, Patel A, et al. Pediatric Delirium and Associated Risk Factors: A Single-Center Prospective Observational Study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015 May;16(4):303–9. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smeets IAP, Tan EYL, Vossen HGM, Leroy PLJM, Lousberg RHB, Os J, et al. Prolonged stay at the paediatric intensive care unit associated with paediatric delirium. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009 Sep 27;19(4):389–93. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colville G, Kerry S, Pierce C. Children’s Factual and Delusional Memories of Intensive Care. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2008 May;177(9):976–82. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200706-857OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kudchadkar SR, Yaster M, Punjabi NM. Sedation, Sleep Promotion, and Delirium Screening Practices in the Care of Mechanically Ventilated Children: A Wake-Up Call for the Pediatric Critical Care Community. Critical Care Medicine. 2014 Jul;42(7):1592–600. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Traube C, Silver G, Kearney J, Patel A, Atkinson TM, Yoon MJ, et al. Cornell Assessment of Pediatric Delirium: A Valid, Rapid, Observational Tool for Screening Delirium in the PICU. Crit Care Med. 2014 Mar;42(3):656–63. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a66b76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith HAB, Boyd J, Fuchs DC, Melvin K, Berry P, Shintani A, et al. Diagnosing delirium in critically ill children: Validity and reliability of the Pediatric Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Med. 2011 Jan;39(1):150–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181feb489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith HAB, Gangopadhyay M, Goben CM, Jacobowski NL, Chestnut MH, Savage S, et al. The Preschool Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU: Valid and Reliable Delirium Monitoring for Critically Ill Infants and Children. Crit Care Med. 2015 Nov;1 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Slater A, Shann F, Pearson G, Paediatric Index of Mortality (PIM) Study Group PIM2: a revised version of the Paediatric Index of Mortality. Intensive Care Med. 2003 Feb;29(2):278–85. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1601-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dominguez TE, Chalom R, Costarino AT., Jr The impact of adverse patient occurrences on hospital costs in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(1):169–74. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200101000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milbrandt EB, Deppen S, Harrison PL, Shintani AK, Speroff T, Stiles RA, et al. Costs associated with delirium in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2004 Apr;32(4):955–62. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000119429.16055.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ely EW, Gautam S, Margolin R, Francis J, May L, Speroff T, et al. The impact of delirium in the intensive care unit on hospital length of stay. Intensive Care Med. 2001 Dec;27(12):1892–900. doi: 10.1007/s00134-001-1132-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trogrlić Z, van der Jagt M, Bakker J, Balas MC, Ely EW, van der Voort PH, et al. A systematic review of implementation strategies for assessment, prevention, and management of ICU delirium and their effect on clinical outcomes. Crit Care [Internet] 2015 Dec; doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0886-9. [cited 2015 Apr 27];19(1). Available from: http://ccforum.com/content/19/1/157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Skrobik Y. Delirium Prevention and Treatment. Anesthesiol Clin. 2011 Dec;29(4):721–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anclin.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brummel NE, Girard TD. Preventing Delirium in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Clin. 2013 Jan;29(1):51–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson BJ, Mikkelsen ME. Duration of Delirium and Patient-Centered Outcomes: Embracing the Short- and Long-Term Perspective. Crit Care Med. 2014 Jun;42(6):1558–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salluh JI, Wang H, Schneider EB, Nagaraja N, Yenokyan G, Damluji A, et al. Outcome of delirium in critically ill patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. bmj. 2015;350:h2538. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schieveld JNM, van Tuijl S, Pikhard T. On Nontraumatic Brain Injury in Pediatric Critical Illness, Neuropsychologic Short-Term Outcome, Delirium, and Resilience. Crit Care Med. 2013 Apr;41(4):1160–1. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827bf658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolters AE, van Dijk D, Pasma W, Cremer OL, Looije MF, de Lange DW, et al. Long-term outcome of delirium during intensive care unit stay in survivors of critical illness: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care. 2014;18(3):R125. doi: 10.1186/cc13929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schieveld JNM, Lousberg R, Berghmans E, Smeets I, Leroy PLJM, Vos GD, et al. Pediatric illness severity measures predict delirium in a pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008 Jun;36(6):1933–6. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817cee5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dasta JF, McLaughlin TP, Mody SH, Piech CT. Daily cost of an intensive care unit day: The contribution of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2005 Jun;33(6):1266–71. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000164543.14619.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehta S, Cook D, Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Meade M, Fergusson D, et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Outcomes of Delirium in Mechanically Ventilated Adults. Crit Care Med. 2015 Mar;43(3):557–66. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.