Abstract

Women who are structurally vulnerable are at heightened risk for HIV/STIs. Identifying typologies of structural vulnerability that drive HIV/STI risk behavior is critical to understanding the nature of women’s risk. Latent class analysis (LCA) was used to classify exotic dancers (n=117) into subgroups based on response patterns of four vulnerability indicators. Latent class regression models tested whether sex- and drug-related risk behavior differed by vulnerability subgroup. Prevalence of vulnerability indicators varied across housing instability (39%), financial insecurity (39%), limited education (67%), and arrest history (36%). LCA yielded a two-class model solution, with 32% of participants expected to belong to a “high vulnerability” subgroup. Dancers in the high vulnerability subgroup were more likely to report sex exchange (OR = 8.1, 95% CI: 1.9, 34.4), multiple sex partnerships (OR = 6.4, 95% CI: 1.9, 21.5), and illicit drug use (OR = 17.4, 95% CI: 2.5, 123.1). Findings underscore the importance of addressing inter-related structural factors contributing to HIV/STI risk.

Keywords: HIV, sexually transmitted infections, social determinants, exotic dance club

Background

In the United States, approximately 50,000 individuals are newly infected with HIV each year [1]. An additional 20 million sexually transmitted infections (STIs) occur annually, leading to substantial disease and associated costs to the U.S. healthcare system [2]. Roughly half of annual STIs are among women, who bear a disproportionate burden of the long-term consequences of untreated HIV and STIs, including pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, and increased risk for certain cancers [2]. New strategies for the targeted control of HIV/STIs are needed, given persistent rates of both HIV and STIs particularly among economically disadvantaged women. A growing body of evidence points to the importance of structural vulnerabilities that predispose women to a heightened risk for HIV and other STIs [3–5]. Broadly, the concept of vulnerability relates societal contexts to an individual’s ability to control health outcomes [6]. Structurally vulnerable women are positioned in society such that they experience a variety of economic, social, gender, and racial discriminations that constrain individual agency for sexual decision-making. As a result of social positioning and restricted sense of agency, structurally vulnerable women are likely to have more exposure to HIV/STI and a lower capacity to protect against infection [3–5, 7].

Structural vulnerability can occur as a result of policies and systems that create disadvantage based on a set of characteristics (e.g., race, gender), and the individual lived experience of structural vulnerability often surfaces as an accumulation of multiple social and economic disadvantages [3–5, 7, 8]. Structurally vulnerable women have limited access to resources such as safe and reliable housing, steady and well-paid employment, and affordable, quality education. Often co-occurring, these mutually reinforcing disadvantages can trigger psychological distress, an urgent need for money, and limited opportunities [9–12]. Women who are highly disadvantaged may be presented with or seek out resources immediately available through existing social or sexual networks, which in certain settings, can introduce HIV/STI related harm. For example, selling sex can provide a source of money when other employment opportunities are limited or unable to meet other needs such as transportation or flexible scheduling [13, 14]. However, the settings in which sex exchange takes place are often characterized by policies, stigma, and discrimination that facilitate unsafe sex and constrain women’s ability to protect themselves against infection [15]. Such structural factors are also rooted in experiences of intimate partner violence and drug use, which are ultimately linked to increased harm and fewer protections against HIV/STIs. Women in relationships with limited sexual power or those who experience sexual violence often have a reduced capacity to protect themselves through consistent condom use [4, 16, 17]. Drug use further complicates such contexts of elevated HIV/STI risk by weakening sexual inhibitions and ability to negotiate condom use with sex partners [18, 19].

However, not all structurally vulnerable women are at heightened risk for HIV/STI, which may be reflective of the intensity at which certain social and economic factors cluster together to synergistically drive drug- and sex- related risk behavior. Identifying the most powerful combinations of social and economic factors, or typologies of structural vulnerability, that drive HIV/STI risk behavior is critical to uncovering profiles of women who are at greatest risk, and thus most in need of targeted prevention and harm reduction services. Women working in the sex industry originate from a range of social and economic backgrounds, and are likely heterogeneous regarding their experiences of structural vulnerability. These women represent a key population through which subgroups characterizing different types of vulnerability may be identified. In the United States and elsewhere, the nature of the sex industry spans a vast range of services, including pornography, online sex, and exotic dance, resulting in varying levels of occupational HIV/STI risk. Female exotic dancers are one group of women in this industry, with research indicating that they move frequently, have inconsistent income, flow in and out of school, and suffer the consequences of a criminal record [20–22]. The accumulation of social and economic disadvantage may render women more susceptible to sex- and drug- related harm when exposed to the exotic dance club (EDC) environment.

Exotic dancers are a unique and diverse group of women, and the most influential social and economic drivers of HIV/STI risk in this population remain unclear. Moreover, the degree to which these factors cluster together, and the synergistic effect of this clustering on HIV/STI risk behavior, has not been explored in depth. Research investigating the interconnected nature of social and economic stressors that may lead to HIV/STI risk behavior is limited, and is particularly scarce among women [11, 23–26]. While a ‘syndemic’ has been traditionally understood and applied to analyze the complex nature of co-occurring health outcomes, a growing body of evidence indicates that HIV/STI risk is grounded within multiple, overlapping economic and social conditions [11, 23, 24, 25, 26]. Applying syndemic theory to the experience of multiple, mutually-reinforcing socioeconomic structural vulnerabilities may add value to the research needed to better understand this context of risk for structurally vulnerable women.

This paper aims to profile dancers’ experiences of structural vulnerability by identifying distinct patterns of co-occurring social and economic disadvantage. Using indicators of structural vulnerability related to housing, finances, education, and arrest, latent class analysis was used to investigate how different indicators cluster together and are associated with drug use and sexual risk behavior. Recognizing the most salient and co-occurring aspects of structural vulnerability is a critical step in identifying women at greatest risk for infection. In addition to guiding targeted HIV/STI programming, this study also has important implications for social policy. The discovery of clusters of modifiable structural drivers of HIV/STI can point to important social and economic issues that if addressed holistically, may reduce HIV/STI transmission across communities most at risk.

Methods

Study population

Participants were purposively recruited from Baltimore City and County EDCs to a cohort for the STILETTOS (STudying the Influence of Location and Environment –Talking Through Opportunities for Safety) Study, investigating the role of the EDC environment on HIV/STI risk. Twenty-two EDCs from which the sample was recruited were classified as high (n=12) and low (n=10) HIV risk based on drug and sex risk profiles previously categorized by a risk environment inventory that used data on the social, policy, drug, and economic environments of the 22 EDCs [27]. Eligibility criteria included: ≥18 years old, danced in exchange for tips for ≤12 months, and danced ≥3 times in the past month, to capture dancers who were most recently exposed to the EDC work environment, and on a somewhat routine basis. Following eligibility determination and providing informed consent, participants (n=117) filled out a 45-minute survey using audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) on a portable tablet. In addition to demographics, drug use, and sexual behavior, surveys collected information about dancers’ recent (past six months) circumstances that were hypothesized to reflect important social and economic aspects of structural vulnerability (e.g., housing, finances). Biological specimens were collected at the time of the survey via self-administered vaginal swab, and tested for gonorrhea (GC) and chlamydia (CT) infection. If any test was positive, participants were referred to Baltimore City Health Department clinic specialists for follow-up. Survey data and biological specimens were collected between May and October 2014, in a variety of locations convenient to participants, including private spaces within EDCs, restaurants, and cars. Participants received a $80 pre-paid debit card for their time. The study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Structural vulnerability

With a particular focus on social and economic aspects of structural vulnerability, indicators were informed by the literature [3, 7, 8, 11, 12, 23, 25, 26] and recent qualitative research exploring the nature of vulnerability among female exotic dancers in Baltimore. To most closely reflect the effects of social and economic policies and systems on the lived experience of structural vulnerability, the most salient, co-occurring indicators of structural vulnerability were hypothesized to include individual circumstances related to housing, finances, education, and the criminal justice system. A total of four binary observed variables, one specific to each of these domains, were selected to represent a composite latent variable of vulnerability. Housing instability was defined by at least one report of the following experiences in the past six months: homelessness, temporary housing type (e.g., shelter, boarding house), or moving more than twice [28]. Financial insecurity was defined as reporting being in debt and behind on rent and/or having borrowed money for rent in the past six months. Limited education (i.e., the extent to which an individual has completed education) was defined as not having graduated high school, received a high school diploma or GED but were not enrolled school, or had some exposure to college but dropped out. Experiences with the criminal justice system were defined by a history of at least one arrest during adulthood.

HIV/STI risk behaviors

Sexual risk behavior variables included report of the following in the past six months: inconsistent condom use with any male sex partner (i.e., exchange, casual, main); multiple (>3) male sex partners; high-risk main male sex partner (i.e., partner engaged in injection drug use (IDU) and/or had multiple sex partners overlapping in time); and engaging in sex exchange. Lifetime (ever) exchanging in sex exchange was also assessed. Drug use was defined by any report of illicit use of prescription opioids (e.g., Percocet, OxyContin), heroin, cocaine, or crack use in the past six months.

Demographic characteristics and other covariates of interest

Demographic variables were age (dichotomized by the median age, 24 years) and race (white vs. non-white). Classifying dancers into two age groups, using the cut point of 24 years, was deemed appropriate considering the disproportionately high STI incidence among young women in Baltimore, as observed in other urban settings throughout the United States [2]. Dancing related variables included overall HIV/STI risk category (high vs. low) of the EDC from which the dancer was recruited, based on the pre-determined risk environment measure [27]. Length of time working as a dancer was examined and dichotomized at the median, four months or less. Women who danced for four months or less were considered to be particularly new to the EDC environment and potentially still adapting to workplace drug- and sex-related norms, compared to more established dancers. Several psychosocial variables were included as factors potentially associated with structural vulnerability and/or HIV/STI risk behavior among the study sample. Childhood sexual and physical abuse was assessed via two physical violence items adapted from the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study [29] and sexual violence items from the Conflict Tactics Scale [30], according to whether women reported having been pushed, grabbed, slapped or hit so hard it left a mark or injury, or reported having been pressured or forced to have sexual contact, before the age of 18. Recent intimate partner violence (IPV) was captured via items adapted from the Conflict Tactics Scale [30], and defined by any report of being physically hurt (e.g., hit, pushed, choked, beaten up) or forced or pressured to have vaginal or anal sex by a main or casual sex partner in the past six months. Health outcomes of interest were self-reported health (excellent or very good) and depression (CESD ≥16) [31, 32].

Analysis

Descriptive statistics for vulnerability indicators, HIV/STI risk behaviors, demographic characteristics, and other covariates of interest were analyzed through examination of distributions, including mean and median for continuous variables (age, number of sex partners), and frequencies for categorical and dichotomous variables. A tetrachoric correlation matrix was estimated to assess the relationships between each pair of indicators, paying careful attention to identifying indicators that could be highly correlated. Because of the multi-level study design that selected dancers from a sample of 22 different EDC environments, we tested for intraclass correlation (ICC) by club for each characteristic. An intercept-only random effects model was used to estimate ICC and determine if there was a need to control for potential clustering observed across characteristics that could be explained by EDC affiliation.

Latent class analysis (LCA) was used to identify and classify women into subgroups, based on their response patterns of the four vulnerability indicators. LCA uses observed indicators to examine different patterns of indicator responses, resulting in unobserved, or latent, classes of individuals. Each class is denoted by conditional probabilities for each indicator to take on a certain response value (e.g., 1 or 0), with the main objective to categorize people into the smallest possible set of distinct and interpretable latent classes [33, 34]. Starting with a one-class model, three models were fit (one, two, and three-classes), and evaluated based on a collection of model fit criteria and interpretability of latent classes. Models beyond three classes did not converge due to the limits of the data, as too many parameters restricted identifiability. The best fitting model was identified according to the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test, Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) [35], the sample size-adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) [36, 37], and the bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT) [33, 34]. The smallest relative AIC and BIC values were considered to indicate better fit, along with significant BLRT p-values comparing the less parsimonious model to the larger model (e.g., 2 class model vs. 3 class model) [33–37]. Entropy was used to assess the extent to which the identified classes were distinct and subjects accurately classified, on range of 0 to 1, with values above 0.8 indicating good model classification [38]. The final selected model was examined to estimate the probabilities of membership in each class, and the probability of each indicator conditional on class membership.

Using bivariate latent class regression (LCR), we tested whether demographic characteristics, EDC risk environment, history of violence, and health status were different for dancers classified as low vulnerability compared to more structurally vulnerable dancers. STI outcomes were not included in the series of bivariate regression models due to small cell sizes. A second set of bivariate latent class regression models were run to determine whether vulnerability class membership was associated with each of the HIV/STI risk behaviors. To treat risk behavior as a dependent distal variable, and predict class specific distributions of each outcome, we transformed the model using an Excel-based LCA outcome probability calculator [39, 40]. This approach allows for estimates of probabilities for each HIV/STI risk behavior by vulnerability class. Small sample size restricted our ability to run multivariable or stratified latent class regression models. Analyses were performed using R version 3.2.0 [41], using the poLCA package [42] and MPLUS version 7 [43].

Results

Descriptive statistics

Among participants (N=117), 40% were age 24 years or older, 35% were white, and 68% were working a high-risk club at baseline (Table 1). Approximately half (48%) reported dancing for four months or less. Experiences of sexual and physical abuse were common, with 44% reporting childhood sexual or physical violence and 31% reporting recent (i.e., in the past six months) IPV. More than one-third (39%) reported recent homelessness, moving more than twice, or sleeping in temporary housing; similarly, 39% had recently borrowed or owed money for rent, and 36% reported a history of arrest. Two-thirds (67%) reported limited education. Intraclass correlation estimates found that the percent variance in each indicator attributed to differences across EDCs was negligible (<0.000), therefore, LCA and LCR models were not grouped by club affiliation.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of study sample, n=117

| Characteristic | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age ≥24 years | 47 | 40.2 |

| Race, White | 41 | 35.0 |

| Dancing related | ||

| Recruited from high-risk exotic dance club | 80 | 68.4 |

| Dancing ≤4 months | 56 | 47.9 |

| History of abuse | ||

| Childhood sexual or physical violence | 51 | 43.6 |

| IPV, past 6 months | 36 | 30.8 |

| Vulnerability indicator | ||

| Housing: homeless, temp housing, >2 moves, past 6 mos. | 45 | 38.5 |

| Financial: borrowed money or behind on rent, past 6 mos. | 46 | 39.3 |

| Education: limited academic achievement* | 78 | 66.7 |

| Arrest: history of arrest in adulthood | 43 | 36.8 |

| Illicit drug use, past 6 months** | 32 | 27.5 |

| Sexual risk behavior, past 6 months | ||

| Inconsistent condom use, any partner | 80 | 68.4 |

| Multiple (>3) male sex partners | 29 | 24.8 |

| High-risk main sex partner (IDU or concurrency) | 28 | 23.9 |

| Sex exchange | 34 | 29.1 |

| Health outcomes | ||

| Self-reported health, excellent/very good | 60 | 51.3 |

| Depression, CESD-16 | 46 | 39.3 |

| Baseline GC/CT infection (N=106) | 10 | 9.4 |

Dancer had not graduated high school, received a high school diploma/GED but was not enrolled school, or had some exposure to college but dropped out

Prescription opioids, heroin, cocaine, crack

GC: gonorrhea, CT: chlamydia

Frequency of inconsistent condom use in the past six months with any partner was common (68%), but varied depending on partner type: 9% with exchange partners, 19% with casual partners, and 65% among main partners [data not shown]. In the past six months, 25% had more than three sex partners and 24% had a high-risk (e.g., partner concurrency or IDU) male sex partner; 29% reported recent sex exchange, and 41% reported ever engaging in sex exchange. Twenty-eight percent of women reported use of prescription opioids, heroin, cocaine, or crack in the past six months. Approximately half of participants (51%) reported excellent or very good health and 39% reported symptoms of depression. Prevalence of bacterial STI (GC or CT) was 9% (N = 106).

Latent class solutions

LCA modeling yielded a two-class model solution, supported by the fit statistics shown in Table 2. The one-class model did not fit the data statistically significantly better than the two-class model, suggesting that the vulnerability indicators could be more appropriately modeled as related within latent subgroups. Compared to a three-class model, the two-class solution demonstrated the best fit to the observed data, given a lower AIC (612.20) and sample size adjusted BIC (608.61). Non-significant LMR and bootstrap likelihood ratio tests (p = 0.404, p=0.250, respectively) also provided evidence against the three-class model as a better fit to the data compared to the more parsimonious two-class solution.

Table 2.

Model fit statistics for 1, 2, and 3 class models, n=117

| Model | Log likelihood | # parameters | LMR p-value | AIC | Adj-BIC | BLRT p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 class | −307.78 | 4 | -- | 623.55 | 621.95 | -- |

| 2 class | −297.10 | 9 | 0.024 | 612.20 | 608.61 | 0.000 |

| 3 class | −294.73 | 14 | 0.404 | 617.47 | 611.88 | 0.250 |

LMR: Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test; BLRT: bootstrap likelihood ratio test.

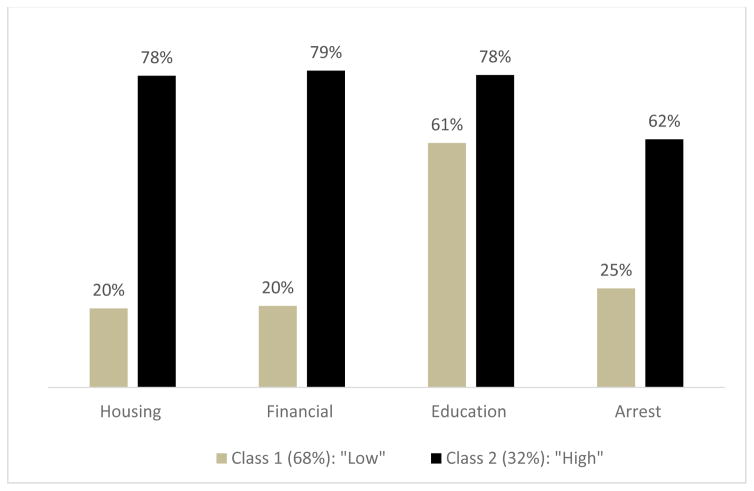

Estimated class prevalence and conditional probability of vulnerability indicators given class membership in the two-class model are presented in Figure 1. The response pattern depicted by low probabilities of housing instability, financial insecurity, history of arrest, and moderate probability of limited education, was identified as the first latent class, and considered the “low vulnerability” subgroup. In contrast, a second latent class, characterized by high probabilities for both housing instability and financial insecurity, and moderate probabilities for limited education and history of arrest, was identified as the “high vulnerability” subgroup. Over two-thirds of the women (68%) were expected to be in the low vulnerability subgroup, and the remaining third (32%) were expected to belong to the high vulnerability subgroup.

Figure 1.

Two-class model: probability of vulnerability indicator, conditional on class membership (n=117)

Covariates associated with vulnerability class membership

Several social and health characteristics were associated with latent class membership (Table 3). Women with recent experiences of IPV and depression were more likely to be classified as highly vulnerable (ORIPV = 13.5, 95% CI: 3.5, 52.0, ORdepress = 10.4, 95% CI: 2.8, 38.9). Age and race were not significantly different across subgroups of vulnerability. However, frequency distributions for dancing at a high-risk club and having a history of child sexual or physical abuse suggested a trend toward differences by class membership although these differences were not statistically significant.

Table 3.

Bivariate analyses of factors associated with latent class membership (n=117)

| Characteristic | Low vulnerability | High vulnerability | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age >24 years | 34.4% | 59.3% | 1.8 (0.6, 5.9) |

| Race, White | 22.0% | 42.1% | 3.8 (0.8, 17.4) |

| Dancing related | |||

| High-risk EDC | 63.2% | 83.3% | 2.6 (0.6, 10.8) |

| Dancing <4 months | 52.5% | 51.5% | 0.8 (0.3, 2.3) |

| History of abuse | |||

| Childhood sexual or physical violence | 34.2% | 59.1% | 2.5 (0.9, 7.3) |

| IPV, past 6 months | 14.1% | 75.0% | 13.5 (3.5, 52.0)* |

| Health status | |||

| General, excellent/very good | 59.3% | 33.3% | 0.4 (0.1, 1.3) |

| Depression | 13.6% | 72.5% | 10.4 (2.8, 38.9)* |

Note: odds ratio compares frequency of given characteristic for dancers expected to be in high vulnerability group vs. low vulnerability subgroup.

p<0.05

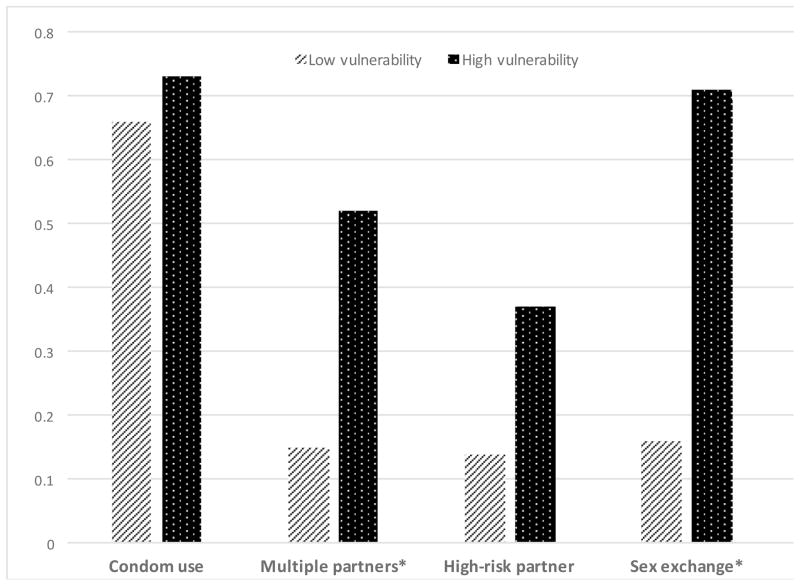

Linking vulnerability class membership to HIV/STI risk behavior

The probability of reporting sexual risk behavior and drug use differed by vulnerability class membership (Figure 2). Specifically, women classified in the high vulnerability class were more likely to report recently having multiple sex partners (52% vs. 15%, p=0.030) and engaging in sex exchange (71% vs. 16%, p=0.017) compared to women who were expected to be in the low vulnerability class. Women in the high vulnerability class were also more likely to report recently using illicit drugs (e.g., prescription opioids, heroin, cocaine, or crack) (57% vs. 7%, p=0.035).

Figure 2. Estimated probability of reporting sexual risk behavior or illicit drug use in the past six months, by class membership.

Multiple partners: >3 male sex partners; high-risk partner: male partner IDU or partner concurrency; drug use: prescription opioids, heroin, cocaine, crack

*p<0.05.

Discussion

This study explored how a set of mutually reinforcing social and economic hardships cluster into distinct underlying subgroups of structural vulnerability. Using housing, finance, education, and arrest related hardship as indicators of structural vulnerability, latent class analysis identified a two-class model. Subgroups were differentiated primarily by housing instability and financial insecurity, followed by arrest history and low education. Notably, one-third of women were expected to belong to the high vulnerability subgroup, represented by high probabilities for both housing instability and financial insecurity, and moderate probabilities for low education and history of arrest. Although education was less distinctive across the two vulnerability groups, it was carefully considered as an important domain of structural vulnerability for inclusion in the model. Not only is access to quality education rooted in the structural contexts in which some women have been limited by economic, gender, or racial discriminations, but opportunities to pursue and complete higher-level training are tightly connected to housing, employment, financial stability, and exposure to the criminal justice system [44, 45].

In addition to a comprehensive set of fit statistics supporting the final two-class model, interpretation was meaningful. Indicators clustered together to form distinct subgroups representing “high” and “low” vulnerability. While the probabilities of housing instability, financial insecurity, and limited educational attainment were substantial (0.78–0.79) among the high vulnerability subgroup, the probability of having an arrest history was not as high (0.62). Moreover, the probability of reporting limited education was less distinct between the two subgroups compared to the other indicators. Low education was common in the sample; therefore, we would expect to see a higher probability of low vulnerability class membership given low education compared to the other indicators. Additionally, although education was included in the model because of the hypothesis that dancers with low education would also be likely to experience housing, financial, and arrest-related instability, it is plausible that some dancers experienced low levels of vulnerability overall, but struggled to access higher educational opportunities. With a larger sample, we may have seen a distinction between this group and another low vulnerability, high education class, for example. The classification of dancers into two distinct groups based on our current model also provided meaning into our investigation of the degree to which different experiences of vulnerability are associated with drug use and sexual risk behavior. Similar findings are reflected in other research. In a study evaluating the role of accumulated vulnerability among low-income urban women, investigators identified two groups, classified according to homelessness, incarceration, monthly income, and residential transience [11]. In a separate but related study, latent class models incorporated having a main partner as an additional indicator, generating a latent construct of accumulated vulnerability that revealed two identifiable subgroups [10].

Latent class analysis not only supported our hypotheses that multiple social and economic indicators of vulnerability are inter-related but also revealed a key group of women most at risk for HIV/STI. Specifically, we classified distinct social and economic profiles of structurally vulnerable women that may be contributing to variations in sex-related risk behavior. Women experiencing an accumulation of social and economic disadvantage at the time of our study were more likely to report recently having multiple sex partners, engaging in sex exchange, and using illicit drugs, compared to women expected to be in the low vulnerability group. Inconsistent condom use was not significantly different across vulnerability groups. This finding is likely due to the grouping of condom use behavior across all sex partners, including casual and trade partners, the majority with whom women reported consistent condom use. Our findings support a continued emphasis on recognizing the multiple layers of contextual factors associated with disparities in HIV/STI, including various social and economic positions (employment, income opportunities, education, gender, race) [46]. Moreover, our results are similar to other studies that have demonstrated how overlapping experiences of social and economic disadvantage can set up a heightened context of risk. German and Latkin found an association between subgroups of social stability and HIV/STI risk among low-income women, using indicators of housing stability, finances, and incarceration [11].

IPV and depression emerged as significant psychosocial factors related to dancers’ vulnerability. Women classified into the high vulnerability subgroup were more likely to have experienced recent IPV and report symptoms of depression. These findings are not surprising in light of previously established links to drug use, sexual behavior, and HIV/STI [47–50]. Future research should explore relationships among IPV, depression, vulnerability, and HIV/STI risk behavior. To carefully address these co-occurring issues, it will be important to elucidate the mechanisms by which experiences of intimate partner violence influence or are influenced by different experiences of vulnerability, including how fluctuations in social and economic disadvantage or chronic disadvantage might be associated. Investigations into how vulnerability is connected to mental health, e.g., depression, may also be informative to identify additional social, economic, and health service needs among this key HIV/STI risk population.

Study findings should be considered in light of some limitations. Small sample size restricted the number of indicators to include in the latent model of vulnerability, in addition to the number of possible classes to evaluate for model fit. As a result, alternative models reflecting different patterns of structural vulnerability may not have been selected. However, the final model was without identifiability issues and allowed for two distinguishable groups. Recent LCA simulations using a sample of 100 subjects to test a 3-class model with five indicators demonstrated good power to predict a correct model and variable classification [33]. Regression analysis was also limited to testing for primarily bivariate associations. Odds ratio estimates were imprecise as indicated by large confidence intervals, particularly for differences in class membership comparing women who did and did not report illicit drug use. A large portion of the women was recruited from high-risk EDCs (68%), which may have resulted in less variability of exposure to sex- and drug-related risk across the sample. However, indicators of vulnerability were not correlated within clubs and vulnerability class membership was not significantly different comparing dancers across high and low risk EDCs. Results demonstrated that social and economic factors are not only connected but function synergistically to amplify exposure to sex- and drug-related risk behavior; however, we did not determine the function by which each of these indicators interact synergistically (e.g., additive, multiplicative). A deeper understanding of these interactions would further inform programs looking to prioritize resources when targeting multiple factors.

Despite limitations, LCA proved a valuable tool for grouping study participants by similar experiences of vulnerability to assess HIV/STI risk. Models highlighted important patterns of social and economic indicators of vulnerability linked to heightened HIV/STI risk in a population, pointing to subgroups at greatest risk and most in need of services. This approach is applicable to HIV/STI programs that seek to improve efficiency of prevention (e.g., risk reduction) and outreach services (e.g., testing, linkage to care and treatment) by targeting groups of people who are at highest risk for infection. In addition to targeted HIV/STI prevention and outreach, structurally vulnerable women, including a considerable portion of female exotic dancers, would also likely benefit from referrals and case management to support safe housing, affordable education and job training programs, and financial management. Programs should consider gender-appropriate approaches that are tailored to address issues that present a challenge for women to benefit from these services if available. For example, women are more likely to be responsible for childcare and other caretaking that can limit the time available to pursue education or job training. Among the dancers in this study, more than one third of women reported having children living at home (data not shown). Evidence from this paper also suggests a need for gender-appropriate integrated psychosocial support services that provide access to mental health care, reduce intimate partner violence, and promote safety for women working within the EDC environment.

Structurally informed policy change is also imperative, as findings underscore the importance of holistically addressing a complex range of co-occurring structural factors contributing to HIV/STI risk. Distinctions in housing and financial instability, limited opportunities for academic achievement, and arrest history highlight an opportunity to improve health through inter-sectoral approaches that address social, economic, and health needs in tandem. The ‘Health in All Policies’ movement calls for new solutions to address the social determinants of health through revitalized policies and structures that facilitate collaboration across government agencies [51]. This approach requires partnerships across agencies such as those involved in the housing, education, criminal justice, and employment sectors to create public policies that promote equitable access to resources [51]. For example, as demonstrated by the King County Health Department in Seattle, Washington, city leaders can spearhead collaboration across education, criminal justice, and housing sectors to create policies designed to improve educational outcomes for students in low-income communities, or reduce incarceration rates and improve employment options for low-income adults [52]. Future research should continue to evaluate and refine both program and policy changes intended to not only disrupt the pathways between vulnerability and HIV/STI risk behavior but also to optimally address the root causes of structural vulnerability across disadvantaged communities.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV Infection in the United States and Dependent Areas, 2014. HIV Surveillance Report. 2015:26. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2012. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhodes T, Wagner K, Strathdee SA, Shannon K, Davidson P, Bourgois P. Structural violence and structural vulnerability within the risk environment: theoretical and methodological perspectives for a social epidemiology of HIV risk among injection drug users and sex workers. In: O’Campo P, Dunn JR, editors. Rethinking Social Epidemiology: Towards a Science of Change. Dordrecht: Springer; 2012. pp. 205–30. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta GR, Ogden J, Warner A. Moving forward on women’s gender-related HIV vulnerability: the good news, the bad news and what to do about it. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(Suppl 3):S370–82. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.617381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta GR, Parkhurst JO, Ogden JA, Aggleton P, Mahal A. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372(9640):764–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blum RW, McNeely C, Nonnemaker J. Vulnerabilty, risk, and protection. J Adolesc Health. 2002;31(1 Suppl):28–39. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00411-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quesada J, Hart LK, Bourgois P. Structural vulnerability and health: Latino migrant laborers in the United States. Med Anthropol. 2011;30(4):339–62. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2011.576725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmes SM. Structural vulnerability and hierarchies of ethnicity and citizenship on the farm. Med Anthropol. 2011;30(4):425–49. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2011.576728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Decker MR, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(7):538–549. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.German D, Latkin CA. Social stability and health: exploring multidimensional social disadvantage. J Urban Health. 2012;89(1):19–35. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9625-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.German D, Latkin CA. Social stability and HIV risk behavior: evaluating the role of accumulated vulnerability. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(1):168–78. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-9882-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aidala A, Cross JE, Stall R, Harre D, Sumartojo E. Housing status and HIV risk behaviors: implications for prevention and policy. AIDS Behav. 2005;9(3):251–65. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9000-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhodes SD, Tanner A, Duck S, et al. Female sex work within the rural immigrant Latino community in the southeast United States: an exploratory qualitative community-based participatory research study. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2012;6(4):417–27. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dank M, Khan B, Downey PM, et al. Estimating the size and structure of the underground commercial sex economy in eight major US cities. The Urban Institute; Washington, DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beyrer C, Crago AL, Bekker LG, et al. An action agenda for HIV and sex workers. Lancet. 2015;385(9964):287–301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60933-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jewkes R, Dunkle K, Nduna M, et al. Factors associated with HIV sero-status in young rural South African women: connections between intimate partner violence and HIV. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(6):1461–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pettifor AE, Measham DM, Rees HV, Padian NS. Sexual power and HIV risk, South Africa. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2004;10(11):1996–2004. doi: 10.3201/eid1011.040252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Gray GE, McIntryre JA, Harlow SD. Transactional sex among women in Soweto, South Africa: prevalence, risk factors and association with HIV infection. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(8):1581–92. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ, Miller WC, Bauer DJ. Sexual and drug behavior patterns and HIV and STD racial disparities: the need for new directions. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):125–32. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.075747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maticka-Tyndale E, Lewis J, Clark JP, Zubick J, Young S. Social and cultural vulnerability to sexually transmitted infection: the work of exotic dancers. Can J Public Health. 1999;90(1):19–22. doi: 10.1007/BF03404092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherman SG, Lilleston P, Reuben J. More than a dance: the production of sexual health risk in the exotic dance clubs in Baltimore, USA. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(3):475–81. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.05.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reuben J, Serio-Chapman C, Welsh C, Matens R, Sherman SG. Correlates of current transactional sex among a sample of female exotic dancers in Baltimore, MD. J Urban Health. 2011;88(2):342–51. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9539-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. AJPH. 2003;93(6):939–942. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reilly ML, German D, Serio-Chapman C, Sherman SG. Structural vulnerabilities to HIV/STI risk among female exotic dancers in Baltimore, Maryland. AIDS Care. 2015;27(6):777–82. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.998613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson PA, Nanin J, Amesty S, Wallace S, Cherenack EM, Fullilove R. Using syndemic theory to understand vulnerability to HIV infection among Black and Latino men in New York City. J Urban Health. 2014;91(5):983–98. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9895-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizuno Y, Purcell DW, Knowlton AR, Wilkinson JD, Gourevitch MN, Knight KR. Syndemic vulnerability, sexual and injection risk behaviors, and HIV continuum of care outcomes in HIV-positive injection drug users. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(4):684–93. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0890-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sherman SG, Duong Q, Taylor R, Reilly ML, Zelaya CE, Huettner S, Ellen J. Measuring a novel STI risk environment: the exotic dance club. STD Prevention Conference; Atlanta, GA. June 10, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 28.German D, Davey M, Latkin C. Residential transience and HIV risk behaviors among injection drug users. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(6 Suppl):21–30. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9238-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–58. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugerman DB. The revised conflict tactics scale (CTS2): development and preliminary psychometric data. J Family Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurements. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB. Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychology and Aging. 1997;12:277–87. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.12.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dziak JJ, Lanza ST, Tan X. Effect size, statistical power and sample size requirements for the bootstrap likelihood ratio test in latent class analysis. Struct Equ Modeling. 2014;21(4):534–552. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2014.919819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Struct Equ Modeling. 2007;14(4):535–69. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Akaike H. Factor analysis and AIC. Psychometrika. 1987;52(3):317–32. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwarz G. Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat. 1978;6:461–4. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sclove L. Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika. 1987;52(3):333–43. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Celeux G, Soromenho G. An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. J Classif. 1996;13:195–212. [Google Scholar]

- 39.LCA outcome probability calculator (Version 1.0) The Methodology Center, Penn State; University Park: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lanza ST, Rhoades BL. Latent class analysis: an alternative perspective on subgroup analysis in prevention and treatment. Prev Sci. 2013;14(2):157–68. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0201-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Linzer DA, Lewis JB. poLCA: An R package for polytomous variable latent class analysis. J Statistical Software. 2011;42(10):1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998–2015. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwartz H, Ecola L, Leuschner KJ, Kofner A. How Housing Matters. MacArthur Foundation; 2014. Inclusionary Zoning Can Bring Poor Families Closer to Good Schools. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cunningham M, MacDonald G. Housing as a Platform for Improving Education Outcomes among Low-Income Children. Urban Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pellowski JA, Kalichman SC, Matthews KA, Adler N. A pandemic of the poor: social disadvantage and the U.S. HIV epidemic. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):197–209. doi: 10.1037/a0032694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El-Bassel Nabila, Gilbert L, Wu E, Hill J. Relationship between drug abuse and intimate partner violence: a longitudinal study among women receiving methadone. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(3):465–70. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.023200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ulibarri MD, Roesch S, Rangel MG, Staines H, Amaro H, Strathdee SA. “Amar te Duele” (“love hurts”): sexual relationship power, intimate partner violence, depression symptoms and HIV risk among female sex workers who use drugs and their non-commercial, steady partners in Mexico. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(1):9–18. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0772-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Decker MR, Miller E, McCauley HL, Tancredi DJ, Anderson H, Levenson RR, Silverman JG. Recent partner violence and sexual and drug-related STI/HIV risk among adolescent and young adult women attending family planning clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;90:145–149. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Illangasekare SL, Burke JG, Chander G, Gielen AC. Depression and social support among women living with the substance abuse, violence, and HIV/AIDS syndemic: a qualitative exploration. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24(5):551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rudolph L, Caplan J, Ben-Moshe K, Dillon L. Health in All Policies: A Guide for State and Local Governments. American Public Health Association and Public Health Institute; Washington, DC and Oakland, CA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wernham A, Teurtsch SM. Health in all policies for big cities. J Public Health Manage Pract. 2015;21(Suppl 1):S56–S65. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0000000000000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]