Abstract

Significant racial/ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality exist in the United States. Black women are three to four times more likely to die a pregnancy-related death as compared with white women. Growing research suggests that hospital quality may be a critical lever for improving outcomes and narrowing disparities. This overview reviews the evidence demonstrating that hospital quality is related to maternal mortality and morbidity, discusses the pathways through which these associations between quality and severe maternal morbidity generate disparities, and concludes with a discussion of possible levers for action to reduce disparities by improving hospital quality.

Keywords: severe maternal morbidity, disparities, quality

Introduction

Racial/ethnic minorities suffer a disproportionate number of maternal deaths as well as other adverse obstetric and perinatal outcomes.1,2 National data has documented that Black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women. This represents the largest disparity among all the conventional population perinatal health measures.2 Disparities are even more marked in New York City where recent data demonstrates a twelve-fold higher risk of pregnancy-related death for blacks than whites.3 Maternal mortality is also elevated among some Native Americans/Native Alaskans, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and for certain subgroups of Latino women including Puerto Ricans.4–6 For every maternal death, 100 women suffer a severe obstetric morbidity, a life threatening diagnosis or undergo a lifesaving procedure during their delivery hospitalization.7 Racial and ethnic disparities also exist in rates of severe maternal morbid events.8

A number of pregnancy complications and comorbidities associated with maternal death are more common among minorities than whites. Blacks experience higher mortality from hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, and cardiomyopathy while Hispanic women have an increased risk of death due to hypertensive disorders.4,9 Minority women have been found to have both higher prevalence and higher case fatality rates for these disorders and for more common problems such as diabetes. A national study which investigated pregnancy-related mortality among black versus white women found that black women had a case-fatality rate 2.4 to 3.3 times higher than that of white women for five specific pregnancy complications including preeclampsia, eclampsia, abruptio placentae, placenta previa, and postpartum hemorrhage.10

A great deal of attention has focused on the role of social determinants of health and their contribution to adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes. Poverty, lack of education, poor nutritional status, smoking, and neighborhood have been associated with poor maternal and infant outcomes.11 Living in an area of higher crime, neighborhood deprivation, or concentrated poverty can impact both maternal health status and the ability to access certain providers for pregnancy and delivery care.12 Our ability to intervene on these factors in the hospital has been limited. But their contribution to overall maternal morbidity and mortality must be considered and addressed.

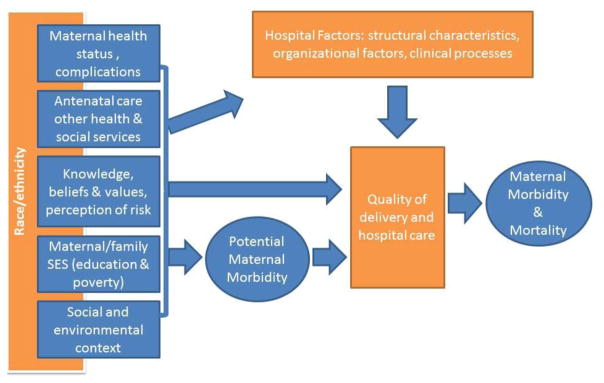

The quality of care provided during the delivery hospitalization may be more amenable to change. Research has demonstrated that provider and system failures explain a significant proportion of maternal deaths and near misses raising the possibility that better hospital quality could improve maternal outcomes and reduce disparities. Figure 1 provides a broad overview of factors that may contribute to pathways linking hospital organization and quality to disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality.

Figure 1.

Pathways Linking Hospital organization and Quality to Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality

To assess whether improving hospital quality may be an effective strategy to reduce disparities in maternal mortality and morbidity, we asked three questions: what is the evidence that hospital quality is related to maternal mortality and morbidity? Through which pathways could associations between quality and adverse maternal outcomes generate disparities between racial and ethnic groups? And, what levers are there for action to reduce disparities by improving hospital quality?

A. Hospital Quality and Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality

1. What is quality and which components of quality impact maternal morbidity and mortality?

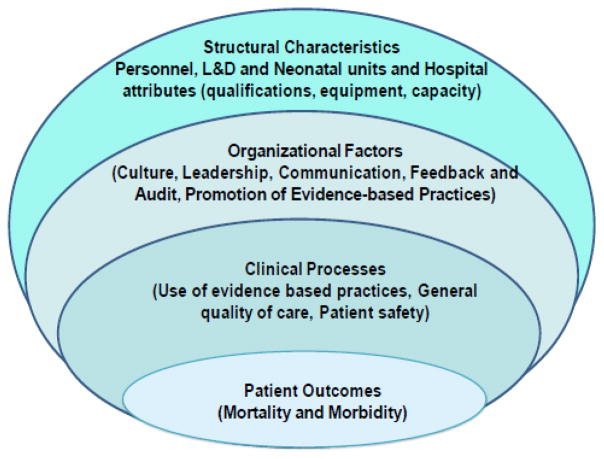

The Institute of Medicine defines healthcare quality as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and care consistent with current professional knowledge.”13 Many government agencies and professional bodies have developed quality measures with the goal of detecting suboptimal care based on the traditional Donabedian model,14 which assesses structure, process, and outcomes. Structural measures are generally applied to characteristics of the care provider including hospitals (e.g. teaching status) or physicians (e.g. board certification). Process measures focus on delivery of specific interventions and services such as medications or procedures. Outcome measures provide information on health outcomes such as mortality, morbidity, and patient experience. Organizational factors including leadership, communication between health providers, and the existence of audit and feedback procedures have been a more recent focus of research on healthcare quality.15,16

Figure 2 schematizes the structural, organizational and clinical process characteristics that have been associated with health outcomes in research on quality of hospital care in other areas of medicine. For instance, there is a large body of research linking structural hospital characteristics to better neonatal outcomes for very low birth weight (VLBW) infants, including designation as a level III neonatal nursery, higher neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) volume and higher VLBW birth volume.17,18 Neonatal outcomes have also been associated with neonatologist-to-house staff ratio, training, workload, and capacity.19–21

Fig 2.

Hospital quality and severe maternal morbidity: structural factors

A growing body of research suggests that organizational factors are associated with high performing hospitals. For example, research on anterior myocardial infarction mortality and hospital care have identified a number of organizational factors that distinguish high performing versus low performing hospitals. Hospitals with greater improvement in beta blocker use over time demonstrated 4 characteristics not found in hospitals with less or no improvement: goals for improvement, substantial administrative support, strong physician leadership advocating beta blocker use, and use of credible feedback.15 In the setting of the NICU, the introduction of quality improvement programs with audit and feedback mechanisms has improved outcomes.22,23 In New York State, all 18 regional referral NICUs adopted central-line insertion and maintenance-bundles and agreed to use checklists to monitor maintenance-bundle adherence and report check list use. Central-line-associated bloodstream infections decreased by two-thirds.23

Variations in rates of severe maternal morbidity exist across hospitals in the U.S.24–26 There have been a limited number of studies investigating the contribution of structural characteristics to these differences, although several have recently demonstrated that lower provider delivery volume is associated with higher severe maternal morbidity rates. In New York City between 2011 and 2013, hospitals in the lowest quartile for delivery volume had higher severe maternal morbidity rates compared to highest volume-quartile hospitals (OR=1.69, 95% CI:1.54–1.85).27 A study in the state of California reported raised risks of severe maternal morbidity for hospitals with <1000 deliveries per year compared to those with 3000+ deliveries of 1.27 (95% CI:1.06–1.52) and 1.15 (95% CI: 1.02–1.31) for hospitals with a delivery volume between 1000 and 3000.28 Using the National Inpatient Survey, Friedman et al. found differences in severe maternal morbidity and deaths associated with severe maternal morbidity in both low and high volume hospitals.29 However, hospital volume explained only a small proportion of the overall hospital-level variation. A study on the same dataset documented increasing risks of severe maternal morbidity over time in hospitals with less than 1000 deliveries a year.26 Finally, the volume of cesareans has also been associated with the risk of anesthesia-related adverse events using data from New York State.30

Fewer studies have explored other hospital structural characteristics and severe maternal morbidity; In France, the absence of a 24-hour on-site anesthesiologist was identified as a risk factor for severe obstetric hemorrhage.31 One study of obstetricians’ residency programs found that women treated by obstetricians trained in lower tier residency programs had adjusted complication rates, including hemorrhage, approximately one-third higher than the women treated by obstetricians from higher-tier programs.32 Severe maternal morbidity rates have also been associated with time of day, with highest rates between 11PM and 7AM, suggesting that staffing or other factors related to shift length or off-hours shifts may contribute to worse outcomes.28 While there is little empirical evidence for the importance of other structural characteristics on severe maternal morbidity, there is a broad consensus on the services (anesthesia services available at all times and on-site ICU) and personnel (maternal–fetal medicine subspecialists, anesthesiologist with special training or experience in obstetric anesthesia) for the care of women with high-risk or complex conditions. These underlie the 2015 recommendations by ACOG and SMFM to introduce maternal levels of care, analogous to those that exist for newborn nurseries.33 However, these levels of care have not yet been used to assess risk of severe maternal morbidity; a recent study of hospital characteristics in California was not able to classify most hospitals into these levels of care as many did not meet the required set of basic criteria.34

3. Hospital quality and severe maternal morbidity: organizational factors and clinical processes

Much of the research on the contribution of organizational factors and clinical processes to maternal deaths or near-misses utilize audits or case reviews. This research from the US and Western Europe suggests that at up to half of maternal deaths might have been prevented through improvements in a variety of areas including provider factors, system factors and patient factors.35–37 Provider-related issues (substandard care as it is referred to in Europe) were the most commonly found factors including failure to diagnose, delays in diagnosis, lack of appropriate referrals, poor documentation and communication. In fact, in a study that examined preventability of maternal death, near miss, and severe morbidity, patient factors were cited in 13% to 20% of preventable cases, system factors were cited in 33% to 47% of preventable events, and provider-related factors were cited for approximately 90% of the preventability in all 3 groups. Incomplete or inappropriate management was the major preventability factor, regardless of the point along the morbidity/mortality continuum.39 A review of cases of severe hemorrhage identified specific components of substandard care and recommended improvement of critical care management including transfusion procedures, repeated laboratory assessments, and protocols for general anesthesia.40 Provider factors were likely related to broader system issues. In a review of maternal deaths in North Carolina, investigators found 40% of pregnancy-related deaths were potentially preventable and the need for higher quality care was a factor in more than one half the preventable deaths.36

In addition to the literature on preventability of maternal morbidity and mortality, there is growing evidence that obstetric complications are sensitive to the quality of care provided at delivery.41,42 Obstetrical processes of care such as use of oxytocin, episiotomy and general anesthesia have been shown to vary widely across hospitals.43 Studies have found tenfold variation in cesarean delivery rates across hospitals.44 Investigators in New York found improved outcomes and fewer maternal deaths after implementing systematic approaches to improve patient safety with regards to obstetric hemorrhage.45 Physicians from the Hospital Corporation of America have described their approach to adverse obstetric outcomes including morbidity and mortality using principles of high reliability organizations. They report improved standardization by the development of highly specific checklist-driven protocols, procedure documentation templates, and mandatory online education modules.46 Protocols for the management of severe hypertension, hemorrhage, and sepsis in obstetric units have been recommended.47 Use of triggers, in an effort to prospectively identify an event that warrants further action such as early warning systems, have been found to improve care.48,49 In other areas of medicine, such as bloodstream infections, an approach based on bundles, or a collection of tools targeted toward a particular morbidity, have been demonstrated to be effective.48 Enhanced communication and teamwork and a safety culture are all important aspects of improved maternal quality and safety.48,50

B. Hospital Quality and Disparities

Differences in hospital quality may contribute to racial and ethnic disparities in maternal mortality and morbidity rates in two ways. First, white and minority women may deliver in separate hospitals and hospitals primarily serving minority women may have structural characteristics associated with lower quality or have organizational models or clinical processes that lead to lower quality care.51 Second, the quality of care received by women during childbirth may differ by race and ethnicity within individual hospitals; these pathways would be less likely to relate to structural characteristics (although providers of care may be different within the same hospital), than organizational and clinical processes which could confer specific disadvantages to minority groups. Nonetheless, whether the disparities are rooted in within or between-hospital differences, underuse of evidence-based interventions, lack of cultural competency among physicians and within the hospital, as well as other quality and safety factors are likely contributors.52 Several audits have identified race/ethnicity or migrant status as a risk factor for suboptimal care, although they did not assess whether this was due to between or within hospital effects.36

A number of studies in other areas of medicine have demonstrated that minorities receive care in different and lower quality hospitals than whites.53,54 Studies of acute myocardial infarction, stroke, and very low birthweight neonatal mortality, have shown that black patients tend to receive care in hospitals with higher mortality rates and lower rates of effective evidence-based medical treatments compared with white patients.54–56 Studies have also demonstrated rates of appropriate care are lower in hospitals with a high proportion of black patients.57,58 These studies suggest that place matters and often attribute disparities to between-hospital differences.

Other studies have demonstrated that health care disparities are explained more by within-hospital differences than between-hospital differences, particularly in the Veterans Affairs setting.59 A study examining cancer care disparities within the Veterans Affairs health care system, observed disparities in cancer care for 7 of 20 cancer-related quality measures among black versus white veterans with cancer. Adjustment for hospital fixed-effects minimally influenced the racial gaps, and the disparities were primarily attributed to within-hospital differences.

1. Between hospital disparities in the setting of severe maternal morbidity

Several recent investigations have found that minority women deliver in different and lower quality hospitals than whites.24,27 In studies by our team using national data, 75% of blacks delivered in a concentrated set of hospitals, whereas only 18% of whites delivered in those same hospitals.24 We ranked hospitals by their proportion of black deliveries into high black-serving (top 5), medium black-serving (5% to 25% range), and low black-serving hospitals and analyzed the risks of severe maternal morbidity for black and white women by hospital black-serving status after adjusting adjusted for patient characteristics, comorbidities, hospital characteristics, and within-hospital clustering. The median percent of black deliveries in high, medium, and black-serving hospitals was 58.6%, 26.4%, and 2.2% respectively. Black and white women who delivered in high and medium black-serving hospitals had elevated rates of severe maternal morbidity rates compared with women who delivered in low black-serving hospitals in adjusted analyses.24 Of note, even after controlling for patient characteristics, clinical comorbidities, and hospital factors, blacks had an elevated rate of severe maternal morbidity as compared with whites and this could reflect within-hospital differences.

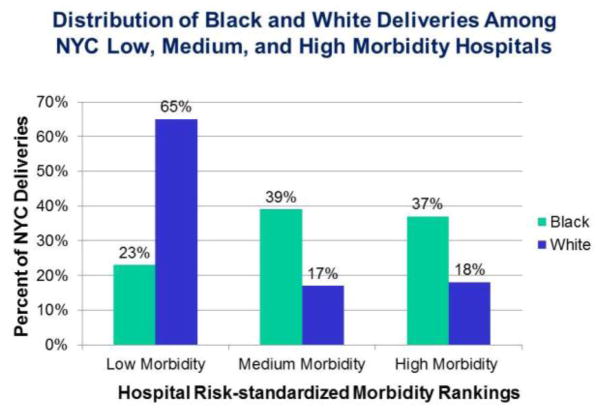

Using another approach for measuring between-hospital differences, we examined where whites and blacks delivered in New York City in relation to hospital morbidity rankings. We ranked hospitals by risk standardized severe maternal morbidity and examined the distribution of deliveries by race. After adjustment for patient case mix, we found seven-fold variation in severe maternal morbidity rates across hospitals; white women were more likely to deliver in the low-morbidity hospitals: 65% of white versus 23% of black deliveries occurred in hospitals in the lowest tertile for morbidity, as illustrated in Figure 3.60

Figure 3.

Distribution of delivery rates by race. Adapted from Howell EA et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016.

In this study, we estimated that black-white differences in delivery location could contribute as much as 47.7% of the racial disparity in severe maternal morbidity rates in New York City.60

2. Within hospital disparities in the setting of severe maternal morbidity

While a number of studies have documented racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality, few have considered the role of between versus within-hospital disparities. A study by Creanga et al. investigated how racial/ethnic minority-serving hospitals performed on 15 delivery-related indicators.25 The authors found significant differences in delivery-related indicators by hospital type and patients’ race/ethnicity. While black serving hospitals performed worse than any other hospitals on 12 of the 15 indicators, indicators varied greatly by race/ethnicity in white and Hispanic serving hospitals, with blacks having 1.19–3.27 and 1.15–2.68 times higher rates than whites for 11 of 15 indicators but few indicator rate differences by race/ethnicity in black-serving hospitals. Within each category of hospitals significant racial/ethnic disparities in delivery-related indicators were reported. This is an example of within-hospital, or in this case, within-hospital category, racial/ethnic disparities in outcomes. Although this study did not specifically examine the extent to which between-hospital versus within-hospital variation contributed to disparities in delivery related indicators, their analysis does show an elevated and unchanged risk for blood transfusions among blacks and Hispanics as compared with whites in white serving hospitals before and after controlling for hospital factors. These findings suggest within-hospital disparities. In addition, their finding that black-serving hospitals had lower quality reflects between-hospital differences which are described above. In our research on between-hospital differences in morbidity, rates of severe maternal morbidity remained elevated for blacks even after accounting for whether the hospital was minority serving or for hospital fixed effects. In the study reported above from New York City, risks of severe maternal morbidity for blacks compared to whites were 1.82 (95% CI 1.69–1.95) after considering hospital structural characteristics and individual hospital effects. Data have demonstrated that both within-hospital and between-hospital disparities exist for severe maternal morbidity.

C. Levers to reduce disparities by improving hospital quality

There is an imperative to improve quality in obstetrics overall, as well as the care we deliver to minority women.61 Research tells us that nearly one-half of maternal mortality and severe events are preventable and hospital quality is a significant lever to improve outcomes, while minority women have been found in numerous studies to be more vulnerable to receiving poor quality care. The Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care and the Alliance for Innovation in Maternal Health (AIM Program) are interdisciplinary groups that include the American Congress (college) of Obstetricians and Gynecologists the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine, American Academy of Family Physicians, American College of Nurse-Midwives, and the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetrics, and Neonatal Nurses as well as others.62 They recently published the “Reduction of Peripartum Racial/Ethnic Disparities Patient Safety Bundle” aimed at reducing disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality. This bundle provides a roadmap and highlights key initiatives that institutions can implement in an attempt to reduce disparities.62

There is considerable overlap between the levers to address between versus within-hospital disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality. First, standardization of care with the implementation of safety bundles (e.g. hemorrhage, venous thrombolic disease, hypertension) is an important step to improving care to all women at all hospitals.48 Triggers, such as maternal early warning criteria, can facilitate timely recognition of and response to acute maternal illness.48,49 Protocols and checklists are recommended to improve quality of care,48,63,64 but more research is needed to determine the most effective strategies. Team training is an important step to providing coordinated care and crew resource management (e.g. TeamSTEPPS) is recommended by the Institute of Medicine, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, AHRQ and The Joint Commission to enhance team training and communication.48 Safety culture, a culture built on a nonjudgmental approach to adverse outcomes and event reviews, is another important aspect of a high quality.50 Safety climate refers to the attitudes and values of the culture and are measured through surveys such as the AHRQ safety culture.50 Improvements in safely culture are correlated with improved patients outcomes in obstetrics.48 Simulation training, such as shoulder dystocia, is recommended as a means to improve knowledge and skills and outcomes. Staff training and credentialing to provide care (such as fetal monitoring) are also suggested.50

As recommended in the AIM bundle as well as others, educating clinicians and staff about shared-decision making, cultural competency, and implicit bias are important steps to address disparities in care. Numerous studies have documented the association between patient experience and outcomes and a first step to enhancing the experience of patients of color is education about effective communication skills. There are toolkits referenced by AIM that address these fundamental issues in clinical care. Implementation of a disparities dashboard, which stratifies quality metrics by race and ethnicity, is a useful tool which allows hospitals and healthcare systems to become aware of disparities within their hospitals and to monitor their performance on quality metrics for groups with higher risks of poor outcomes.65 This should be accompanied by quality improvement activities to target disparities. For example, the Mass General Hospital utilized their disparities dashboard to identify disparities in diabetic screening among Hispanics, and then implemented a program to address this disparity.65 There is also growing evidence that programs that partner with communities may have a substantial impact on improving quality and reducing disparities.66

Given the scarcity of resources and the importance of reducing disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality the question arises about whether we should implement the recommended strategies at all hospitals or at hospitals that disproportionately serve minorities. We would argue that it is important to implement these strategies at all hospitals with a particular emphasis on low performing hospitals rather than minority-serving hospitals. The minority-serving approach is often based on arbitrary and varying thresholds for defining minority-serving, as there are no theoretical guidelines for making these decisions. Further, while targeting minority serving hospitals ensures that minorities benefit most from interventions, these hospitals do not necessarily represent the hospitals where most minorities are receiving care in a specific community, especially when they have low volumes of deliveries. Research simulating the impact of these two approaches has illustrated a higher impact with more wide-reaching quality initiatives.67

Conclusion

Recent high profile publications call for action by the healthcare system to reduce disparities and acknowledge the role that structural racism and segregation contribute to health disparities.61 Researchers in obstetrics have documented racial/ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and mortality and it is now time for action. We have reviewed the evidence that demonstrates that hospital quality is related to maternal mortality and morbidity, how disparities can be generated by between and within-hospital differences, and the evidence base for potential levers to reduce disparities and improve quality. We argue that a comprehensive approach to quality improvement with special emphasis on improving the lowest performers is likely to have the most benefit.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant number R01MD007651 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010 Apr;202(4):335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.10.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callaghan WM. Overview of maternal mortality in the United States. Semin Perinatol. 2012 Feb;36(1):2–6. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Bureau of Maternal and Child Health. Pregnancy-Associated Mortality New York City, 2006–2010. New York: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hopkins FW, MacKay AP, Koonin LM, Berg CJ, Irwin M, Atrash HK. Pregnancy-related mortality in Hispanic women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 1999 Nov;94(5 Pt 1):747–752. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00393-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC. Pregnancy-related deaths among Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native women--United States, 1991–1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001 May 11;50(18):361–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray KE, Wallace ER, Nelson KR, Reed SD, Schiff MA. Population-based study of risk factors for severe maternal morbidity. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012 Nov;26(6):506–514. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Callaghan WM, Creanga AA, Kuklina EV. Severe maternal morbidity among delivery and postpartum hospitalizations in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Nov;120(5):1029–1036. doi: 10.1097/aog.0b013e31826d60c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Creanga AA, Bateman BT, Kuklina EV, Callaghan WM. Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity: a multistate analysis, 2008–2010. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 May;210(5):435, e431–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harper MA, Espeland MA, Dugan E, Meyer R, Lane K, Williams S. Racial disparity in pregnancy-related mortality following a live birth outcome. Ann Epidemiol. 2004 Apr;14(4):274–279. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tucker MJ, Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Hsia J. The Black–White Disparity in Pregnancy-Related Mortality From 5 Conditions: Differences in Prevalence and Case-Fatality Rates. American Journal of Public Health. 2007 2007-02/01;97(2):247–251. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute of Medicine. Preterm births: Causes, consequences and prevention. Washington, D.C: The National Academy of Science; Jul 13, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kramer MR, Hogue CR. What causes racial disparities in very preterm birth? A biosocial perspective. Epidemiol Rev. 2009;31:84–98. doi: 10.1093/ajerev/mxp003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lohr K, editor. Medicare: a strategy for quality assurance. Washington D.C: Institute of Medicine; 1990. CtDaSfQRaAiM. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulkedid R, Alberti C, Sibony O. Quality indicator development and implementation in maternity units. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2013 Aug;27(4):609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley EH, Holmboe ES, Mattera JA, Roumanis SA, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. A qualitative study of increasing beta-blocker use after myocardial infarction: Why do some hospitals succeed? JAMA. 2001 May 23–30;285(20):2604–2611. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.20.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curry LA, Spatz E, Cherlin E, et al. What distinguishes top-performing hospitals in acute myocardial infarction mortality rates? A qualitative study. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Mar 15;154(6):384–390. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-6-201103150-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogowski JA, Horbar JD, Staiger DO, Kenny M, Carpenter J, Geppert J. Indirect vs direct hospital quality indicators for very low-birth-weight infants. JAMA. 2004 Jan 14;291(2):202–209. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lasswell SM, Barfield WD, Rochat RW, Blackmon L. Perinatal regionalization for very low-birth-weight and very preterm infants: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010 Sep 1;304(9):992–1000. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tucker J. Patient volume, staffing, and workload in relation to risk-adjusted outcomes in a random stratified sample of UK neonatal intensive care units: a prospective evaluation. Lancet. 2002 Jan 12;359(9301):99–107. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grandi C, Gonzalez A, Meritano J. Patient volume, medical and nursing staffing and its relationship with risk-adjusted outcomes of VLBW infants in 15 Neocosur neonatal network NICUs. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2010 Dec;108(6):499–510. doi: 10.1590/S0325-00752010000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Synnes AR, Macnab YC, Qiu Z, et al. Neonatal intensive care unit characteristics affect the incidence of severe intraventricular hemorrhage. Med Care. 2006 Aug;44(8):754–759. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000218780.16064.df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wirtschafter DD, Powers RJ, Pettit JS, et al. Nosocomial infection reduction in VLBW infants with a statewide quality-improvement model. Pediatrics. 2011 Mar;127(3):419–426. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schulman J, Stricof R, Stevens TP, et al. Statewide NICU central-line-associated bloodstream infection rates decline after bundles and checklists. Pediatrics. 2011 Mar;127(3):436–444. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howell EA, Egorova N, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Black-white differences in severe maternal morbidity and site of care. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jan;214(1):122, e121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Creanga AA, Bateman BT, Mhyre JM, Kuklina E, Shilkrut A, Callaghan WM. Performance of racial and ethnic minority-serving hospitals on delivery-related indicators. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jun 5; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hehir MP, Ananth CV, Wright JD, Siddiq Z, D’Alton ME, Friedman AM. Severe Maternal Morbidity and Comorbid Risk in Hospitals Performing <1000 Deliveries Per Year. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howell EA, Egorova NN, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Site of delivery contribution to black-white severe maternal morbidity disparity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Aug;215(2):143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyndon A, Lee HC, Gay C, Gilbert WM, Gould JB, Lee KA. Effect of time of birth on maternal morbidity during childbirth hospitalization in California. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2015;213(5):705.e701–705.e711. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Friedman AM, Ananth CV, Huang Y, D’Alton ME, Wright JD. Hospital delivery volume, severe obstetrical morbidity, and failure to rescue. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guglielminotti J, Deneux-Tharaux C, Wong CA, Li G. Hospital-Level Factors Associated with Anesthesia-Related Adverse Events in Cesarean Deliveries, New York State, 2009–2011. Anesth Analg. 2016 Jun;122(6):1947–1956. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouvier-Colle M-H, Ould El Joud D, Varnoux N, et al. Evaluation of the quality of care for severe obstetrical haemorrhage in three French regions. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2001;108(9):898–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asch DA, Nicholson S, Srinivas S, Herrin J, Epstein AJ. Evaluating obstetrical residency programs using patient outcomes. JAMA. 2009 Sep 23;302(12):1277–1283. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Menard MK, Kilpatrick S, Saade G, et al. Levels of maternal care. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2015;212(3):259–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korst LM, Feldman DS, Bollman DL, et al. Variation in childbirth services in California: a cross-sectional survey of childbirth hospitals. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2015;213(4):523.e521–523.e528. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis G, Drife J, Assessors C. Why mothers die: Report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in the United Kingdom, 1997–1999. London: Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berg CJ, Harper MA, Atkinson SM, et al. Preventability of pregnancy-related deaths: results of a state-wide review. Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Dec;106(6):1228–1234. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000187894.71913.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berg CJ, Atrash HK, Koonin LM, Tucker M. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1987–1990. Obstet Gynecol. 1996 Aug;88(2):161–167. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00135-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geller SE, Cox SM, Callaghan WM, Berg CJ. Morbidity and mortality in pregnancy: laying the groundwork for safe motherhood. Womens Health Issues. 2006 Jul-Aug;16(4):176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geller SE, Rosenberg D, Cox SM, et al. The continuum of maternal morbidity and mortality: factors associated with severity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004 Sep;191(3):939–944. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bonnet M-P, Deneux-Tharaux C, Bouvier-Colle M-H. Critical care and transfusion management in maternal deaths from postpartum haemorrhage. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2011;158(2):183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guendelman S, Thornton D, Gould J, Hosang N. Obstetric complications during labor and delivery: assessing ethnic differences in California. Womens Health Issues. 2006 Jul-Aug;16(4):189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kramer M, Rouleau J, Liu S, Bartholomew S, Joseph K. Amniotic fluid embolism: incidence, risk factors, and impact on perinatal outcome. BJOG. 2012 Jun;119(7):874–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grobman WA, Bailit JL, Rice MM, et al. Can differences in obstetric outcomes be explained by differences in the care provided? The MFMU Network APEX Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Mar 11; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kozhimannil KB, Law MR, Virnig BA. Cesarean delivery rates vary tenfold among US hospitals; reducing variation may address quality and cost issues. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013 Mar;32(3):527–535. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skupski DW, Lowenwirt IP, Weinbaum FI, Brodsky D, Danek M, Eglinton GS. Improving hospital systems for the care of women with major obstetric hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2006 May;107(5):977–983. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000215561.68257.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clark SL, Belfort MA, Byrum SL, Meyers JA, Perlin JB. Improved outcomes, fewer cesarean deliveries, and reduced litigation: results of a new paradigm in patient safety. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Aug;199(2):105, e101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baskett TF, Sternadel J. Maternal intensive care and near-miss mortality in obstetrics. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 1998;105(9):981–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arora KS, Shields LE, Grobman WA, D’Alton ME, Lappen JR, Mercer BM. Triggers, Bundles, Protocols, and Checklists - What Every Maternal Care Provider Needs to Know. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Oct 15; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mhyre JM, D’Oria R, Hameed AB, et al. The maternal early warning criteria: a proposal from the national partnership for maternal safety. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Oct;124(4):782–786. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pettker CM, Grobman WA. Obstetric Safety and Quality. Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Jul;126(1):196–206. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Howell EA. Racial disparities in infant mortality: a quality of care perspective. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008 Jan-Feb;75(1):31–35. doi: 10.1002/msj.20018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Halm EA, Tuhrim S, Wang JJ, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in outcomes and appropriateness of carotid endarterectomy: impact of patient and provider factors. Stroke. 2009 Jul;40(7):2493–2501. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.544866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Howell EA, Hebert P, Chatterjee S, Kleinman LC, Chassin MR. Black/white differences in very low birth weight neonatal mortality rates among New York City hospitals. Pediatrics. 2008 Mar;121(3):e407–415. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-0910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Morales LS, Staiger D, Horbar JD, et al. Mortality among very low-birthweight infants in hospitals serving minority populations. Am J Public Health. 2005 Dec;95(12):2206–2212. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.046730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barnato AE, Lucas FL, Staiger D, Wennberg DE, Chandra A. Hospital-level racial disparities in acute myocardial infarction treatment and outcomes. Med Care. 2005 Apr;43(4):308–319. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000156848.62086.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stansbury JP, Jia H, Williams LS, Vogel WB, Duncan PW. Ethnic disparities in stroke: epidemiology, acute care, and postacute outcomes. Stroke. 2005 Feb;36(2):374–386. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000153065.39325.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cheng EM, Keyhani S, Ofner S, et al. Lower use of carotid artery imaging at minority-serving hospitals. Neurology. 2012 Jul 10;79(2):138–144. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825f04c5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Li Z, Epstein AM. Concentration and quality of hospitals that care for elderly black patients. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007 Jun;167(11):1177–1182. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Samuel CA, Landrum MB, McNeil BJ, Bozeman SR, Williams CD, Keating NL. Racial disparities in cancer care in the Veterans Affairs health care system and the role of site of care. Am J Public Health. 2014 Sep;104(Suppl 4):S562–571. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Howell EA, Egorova NN, Balbierz A, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL. Site of delivery contribution to black-white severe maternal morbidity disparity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 May 12; doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eichelberger KY, Doll K, Ekpo GE, Zerden ML. Black Lives Matter: Claiming a Space for Evidence-Based Outrage in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Am J Public Health. 2016 Oct;106(10):1771–1772. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM) [Accessed October 30, 2016, 2016];Safe Health Care for Every Woman. 2015 http://www.safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/aim.php.

- 63.Clark SL. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality. Semin Perinatol. 2012 Feb;36(1):42–47. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lappen JR, Seidman D, Burke C, Goetz K, Grobman WA. Changes in care associated with the introduction of a postpartum hemorrhage patient safety program. Am J Perinatol. 2013 Nov;30(10):833–838. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1333674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mass General Hospital Institute for Health Policy. [Accessed November 1, 2016];Improving Quality and Achievning Equity: A Guide for Hospital Leaders. http://www2.massgeneral.org/disparitiessolutions/z_files/disparities%20leadership%20guide_final.pdf.

- 66.Peek ME, Ferguson M, Bergeron N, Maltby D, Chin MH. Integrated community-healthcare diabetes interventions to reduce disparities. Curr Diab Rep. 2014 Mar;14(3):467. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0467-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hebert PL, Howell EA, Wong ES, et al. Methods for Measuring Racial Differences in Hospitals Outcomes Attributable to Disparities in Use of High-Quality Hospital Care. Health Serv Res. 2016 Jun 3; doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]