Abstract

Four Burkholderia pseudomallei-like isolates of human clinical origin were examined by a polyphasic taxonomic approach that included comparative whole genome analyses. The results demonstrated that these isolates represent a rare and unusual, novel Burkholderia species for which we propose the name B. singularis. The type strain is LMG 28154T (=CCUG 65685T). Its genome sequence has an average mol% G+C content of 64.34%, which is considerably lower than that of other Burkholderia species. The reduced G+C content of strain LMG 28154T was characterized by a genome wide AT bias that was not due to reduced GC-biased gene conversion or reductive genome evolution, but might have been caused by an altered DNA base excision repair pathway. B. singularis can be differentiated from other Burkholderia species by multilocus sequence analysis, MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and a distinctive biochemical profile that includes the absence of nitrate reduction, a mucoid appearance on Columbia sheep blood agar, and a slowly positive oxidase reaction. Comparisons with publicly available whole genome sequences demonstrated that strain TSV85, an Australian water isolate, also represents the same species and therefore, to date, B. singularis has been recovered from human or environmental samples on three continents.

Keywords: Burkholderia singularis, whole genome sequence, cystic fibrosis microbiology, comparative genomics, Burkholderia pseudomallei complex, Burkholderia cepacia complex

Introduction

A variety of Gram-negative non-fermenting bacteria can colonize the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis (CF) (Lipuma, 2010; Parkins and Floto, 2015). The majority of these bacteria are considered opportunists but correct species identification is paramount for the management of infections in these patients. More than twenty Burkholderia species have been retrieved from respiratory samples of patients with CF, with B. cenocepacia and B. pseudomallei the major concerns (O’Carroll et al., 2003; Lipuma, 2010). When the genus Burkholderia was created in 1992 it consisted of only seven species which were primarily known as human, animal, and plant pathogens (Yabuuchi et al., 1992). They proved, however, to be metabolically versatile and biotechnologically appealing, and a large number of novel Burkholderia species were subsequently isolated and formally named. The genus Burkholderia now comprises about 100 validly named species1 and many uncultivated candidate species, which occupy extremely diverse ecological niches (Coenye and Vandamme, 2003; Compant et al., 2008; Suarez-Moreno et al., 2012).

Although their metabolic potential can be exploited for biocontrol, bioremediation and plant growth promotion, Burkholderia species are notorious opportunistic pathogens in immunocompromised patients and cause pseudo-outbreaks through their impressive capacity to contaminate pharmaceutical products (Coenye and Vandamme, 2003; Torbeck et al., 2011; Depoorter et al., 2016). The use of Burkholderia in agricultural applications is therefore controversial and considerable effort has been invested to discriminate beneficial from clinical Burkholderia strains (Baldwin et al., 2007; Mahenthiralingam et al., 2008). Recently, the phylogenetic diversity within this genus, as revealed through comparative 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene studies, was used to subdivide this genus into Burkholderia sensu stricto (which comprises the majority of human pathogens) and several novel genera, i.e., Paraburkholderia, Caballeronia, and Robbsia (Sawana et al., 2014; Dobritsa and Samadpour, 2016; Lopes-Santos et al., 2017). This 16S rRNA sequence based subdivision was supported by a difference in genomic G+C content: Burkholderia sensu stricto species have a genomic G+C content of 65.7 to 68.5%, whereas the genera Paraburkholderia, Caballeronia and Robbsia have a genomic G+C content of about 61.4–65.0%, 58.9–65.0%, and 58.9%, respectively.

In our studies of the biodiversity of Burkholderia strains that are recovered from samples of CF patients, we received isolates from a Canadian and a German patient that proved difficult to identify using conventional phenotyping and genotyping methods. Although first considered B. cepacia-like bacteria, partial 16S rRNA gene sequencing revealed that they were more closely related to B. pseudomallei. The present study provides detailed genotypic and phenotypic characterization of this novel bacterium and shows that it has genomic signatures that defy the recent dissection of the genus Burkholderia.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

The isolates R-20802 (=VC11777), LMG 28154T (=VC12093) and R-50762 (=VC15152) are serial isolates from respiratory samples of the same Canadian CF patient and were collected in March 2003, October 2003 and 2009, respectively (Table 1). Isolate LMG 28155 was obtained from a German CF patient in 2008. Strains were grown aerobically on Tryptone Soya Agar (Oxoid) and were routinely incubated at 28°C. Cultures were preserved in MicroBankTM vials at -80°C until lyophilization.

Table 1.

Isolates studied, their sources, sequence types and allelic profiles.

| Strain1 | Other strain designations | Source2 | Depositor | ST3 | Allelic profile | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Country, year of isolation) | atpD | gltB | gyrB | recA | lepA | phaC | trpB | ||||

| LMG 28154T | VC11777T, CCUG 65685T | CF (Canada, 2003) | Current study | 813 | 337 | 391 | 583 | 355 | 407 | 311 | 393 |

| R-20802 | VC12093 | CF (Canada, 2003) | Current study | 813 | 337 | 391 | 583 | 355 | 407 | 311 | 393 |

| R-50762 | VC15152 | CF (Canada, 2009) | Current study | 813 | 337 | 391 | 583 | 355 | 407 | 311 | 393 |

| LMG 28155 | 848157/5638 | CF (Germany, 2008) | L. Sedlacek | 815 | 338 | 392 | 584 | 356 | 408 | 311 | 394 |

| TSV85 | Water (Australia, 2010) | Current study | 1295 | 404 | 564 | 848 | 481 | 524 | 311 | 524 | |

1LMG, BCCM/LMG Bacteria Collection, Laboratory of Microbiology, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium; CCUG, Culture Collection University of Gothenburg, Department of Clinical Bacteriology, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden.

2CF, isolated from a cystic fibrosis patient.

3Based on the B. cepacia complex scheme (https://pubmlst.org/bcc/).

16S rRNA Gene Sequence Analysis

The 16S rRNA gene sequences of strains LMG 28154T and LMG 28155 were determined as described by Vandamme et al. (2007). Sequence assembly was performed using the BioNumerics v7 software. EzBioCloud was used to identify the nearest neighbor taxa with validly published names (Yoon et al., 2017). The 16S rRNA sequences of two strains without taxonomic standing, i.e., Burkholderia sp. TSV85 (GenBank accession GCA_001523725.1) and Burkholderia sp. TSV86 (GenBank accession GCA_001522865.1), were retrieved from their whole genome sequences as preliminary analysis of genome sequences indicated a close phylogenetic relationship to strain LMG 28154T. The 16S rRNA sequences of strains LMG 28154T, LMG 28155, TSV85, TSV86 and Burkholderia representatives (1011–1610 bp) were aligned against the SILVA SSU reference database using SINA v1.2.112 (Pruesse et al., 2012). Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using MEGA7 (Kumar et al., 2016). All positions with <95% site coverage were eliminated, resulting in a total of 1311 positions in the final dataset. The statistical reliability of tree topologies was evaluated by bootstrapping analysis based on 1000 replicates.

MLST Analysis

MLST analysis was based on the method described by Spilker et al. (2009) with small modifications as described earlier (Peeters et al., 2013). Nucleotide sequences of each allele, allelic profiles and sequence types for all isolates from the present study are available on the B. cepacia complex PubMLST website3 (Jolley et al., 2004; Jolley and Maiden, 2010). Although most closely related to B. pseudomallei complex species according to 16S rRNA and whole genome phylogenies, strains LMG 28154T, TSV85 and TSV86 were not able to be genotyped with the B. pseudomallei PubMLST scheme4 due to the absence of the narK locus, consistent with other non-B. pseudomallei complex species (Price et al., 2016).

Genome Sequencing, Assembly and Annotation

Strain LMG 28154T was grown for 48 h on chocolate agar (Oxoid) and genomic DNA was prepared by the CTAB and phenol:chloroform purification method (Currie et al., 2007). Paired-end 100 bp libraries were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq2000 sequencer (Macrogen Inc., Geumcheon-gu, Seoul, South Korea). Sequencing reads were quality-filtered and assembled as described earlier (Carlier et al., 2016). Briefly, the reads were prepared for assembly using the adapter trimming function of the Trimmomatic software (Bolger et al., 2014) and sequencing reads with a Phred score below 20 were discarded. The trimmed reads were used for de novo assembly using SPAdes v3.0 assembler with k-mer lengths of 21, 33, 55, 77, and 89 (Bankevich et al., 2012). The QUAST program was used to generate the summary statistics of the assembly (N50, maximum contig length, GC) (Gurevich et al., 2013). Trimmed reads were mapped back to the assembled contigs using the SMALT software5 and mapping information was extracted using the Samtools software suite. Contigs <500 bp and with <35× coverage were discarded. Final contigs were checked for contamination against common contaminants (e.g., PhiX 174 genome sequence) and submitted for annotation to the RAST online service (Aziz et al., 2008) with gene prediction option enabled. Annotated contig sequences were manually curated in the Artemis software (Carver et al., 2008). Annotated contigs were deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive6 with the accession numbers FXAN01000001–FXAN01000135. Raw sequencing reads are available under accession ERR1923794.

Ortholog computations were done with the Orthomcl v1.4 software (Li et al., 2003), using the NCBI Blastp software (Altschul et al., 1997) with e-value cut-off of 1.0 × 10-6 and a percentage identity cut-off of 50%. Assignment of Clusters of Orthologous Genes (COG) functional categories was done by searching protein sequences in the COG database (Galperin et al., 2015) using the NCBI rpsblast software with an e-value cut-off of 10-3. COG accessions were searched in the STRING v10 database (von Mering et al., 2005) and interaction networks were drawn by selecting neighborhood and co-expression interaction sources. Genes belonging to each COG category were counted and the distributions were compared using a Pearson’s chi-squared test run with the R software package (R Core Team, 2014).

Putative pseudogenes were predicted as described earlier (Pinto-Carbo et al., 2016). Briefly, predicted genes were searched against a database of Burkholderia orthologs calculated as described above and intergenic regions using BLASTx (Altschul et al., 1990) against a custom database of protein sequences predicted from Burkholderia genomes. Only hits with >50% identity and with an e-value < 10-6 were considered. Hit regions were aligned with the best-scoring subject protein sequence using the tfasty program of the FASTA software suite v3.6 in order to find the boundaries of the pseudogenes (Pearson, 2000). Hits with <80% of the ORF length intact (either due to frameshift or early stop codon) were considered putative pseudogenes.

Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) Values

Calculation of ANI values was done on a whole genome sequence database of Burkholderia species (type strains if genome sequence was available at the time of analysis, otherwise representative genome sequence as listed by NCBI GenBank): B. thailandensis E264T (GenBank accession GCA_000012365.1), B. pseudomallei K96243 (GenBank accession GCA_000011545.1), B. oklahomensis C6786T (GenBank accession GCA_000170375.1), B. mallei ATCC 23344T (GenBank accession GCA_000011705.1), B. humptydooensis MSMB43T (GenBank accession GCA_001513745.1), Burkholderia sp. TSV85 (GenBank accession GCA_001523725.1) and Burkholderia sp. TSV86 (GenBank accession GCA_001522865.1). The draft assembly data of strain LMG 28154T in FASTA format was uploaded to the JSpeciesWS website (Richter and Rossello-Mora, 2009). ANI analysis was performed with the ANIb algorithm (Goris et al., 2007) accessible via the JSpeciesWS web service (Richter and Rossello-Mora, 2009).

Whole Genome Phylogeny

Representative genomes from individual Burkholderia, Paraburkholderia, Caballeronia and Robbsia species were downloaded from the NCBI RefSeq database (accessed Feb. 2017). In addition, genomes from strains LMG 28154T, TSV85 and TSV86 were added to the database. Nucleotide and amino acid sequences of annotated CDS were extracted and searched against a database of 40 nearly universal, single copy gene markers using the FetchMG program with the –v flag to retain only the best hits (Sunagawa et al., 2013). Twenty-three COGs present in all genomes were extracted, aligned with Clustal Omega and the resulting alignments were concatenated using the AlignIO utility of Biopython (Cock et al., 2009). The concatenated alignment was trimmed with TrimAl (Capella-Gutierrez et al., 2009) to remove columns with >10% gaps and poorly aligned sections of the alignment were removed manually in CLC Main Workbench v.7.7 (Qiagen, Aarhus, Denmark). A concatenated nucleotide alignment of 15092 bp was used to build a phylogenetic tree with FastTree, using the GTR CAT model (Price et al., 2010). The tree was edited in iTOL (Letunic and Bork, 2016).

G+C Content and Evolutionary Rates Analysis

Overall mol% G+C was calculated from the final set of genome contigs using the Quast software (Gurevich et al., 2013). Intra-genome %G+C distributions were calculated on non-overlapping 1-kb fragments using ad hoc Python scripts. Extreme values were discarded for clarity, and the median and quartile values, as well as the estimated size of the genomes were plotted together with the phylogenetic tree using the iTol v3 web server (Letunic and Bork, 2016). Putative orthologs between the genomes of strain LMG 28154T, B. thailandensis E264T, B. pseudomallei K96243, B. oklahomensis C6786T, Burkholderia sp. TSV86 and B. glumae BGR1 (Genbank accession GCA_000022645.2) were calculated using the Orthomcl software as described above. Single copy orthologs from each genome were selected and the protein sequences were aligned using MUSCLE with standard settings (Edgar, 2004) and back-translated into nucleotide alignments using T-Coffee (Notredame et al., 2000). Poorly aligned regions and gaps were trimmed using the TrimAl software (Capella-Gutierrez et al., 2009) and overall G+C content as well as G+C content for each codon position were calculated using ad hoc Python 2.7.3 scripts (scripts available upon request). Statistical tests were performed with the R software package version 3.1.0 (R Core Team, 2014), including the pgirmess package for non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests (Giraudoux, 2013). Statistical tests for recombination were conducted on the trimmed nucleotide alignments for each single copy orthologous groups using the PhiPack software (Bruen et al., 2006) and the p-values were calculated with 1000 permutations and a 100 bp window. Alignments which failed the permutation test were discarded and a p-value < 0.05 was considered as evidence of recombination. Only orthologous groups without statistical evidence of recombination (p-value > 0.05) were used for the calculation of evolutionary rates.

Rates of synonymous (dS) and non-synonymous (dN) substitutions were estimated for the gene families with strictly one ortholog in each of the eight species. Protein sequences for each ortholog cluster were aligned with MUSCLE and subsequent nucleotide codon alignments were generated and trimmed using Pal2nal perl script (Suyama et al., 2006).

Pairwise dN/dS values were estimated with the yn00 module of the PAML v4.4 package (Yang, 2007) using the Yang and Nielsen (2000) method. Pairs of orthologs with insufficient levels of divergence (dS < 0.1) or near saturation (dS > 1) were excluded from the analyses. Pairwise ratios of non-synonymous to synonymous (dN/dS) mutations were extracted from the PAML output using ad hoc Python scripts and plotted in R. Non-parametric Wilcoxon signed rank tests were performed to test whether dN/dS values were higher for genes in the novel species compared to free-living Burkholderia (null hypothesis).

Codon frequencies were calculated on sets of orthologous genes that did not show evidence of recombination (n = 2890) with the Cusp program of the Emboss toolkit (Rice et al., 2000). Only fourfold degenerate codons were considered for analysis. Statistical analyses were done in R.

For the calculation of substitution bias in intergenic regions, we selected a random set of 17 intergenic regions which were conserved in strains LMG 28154T, TSV85 and TSV86, and did not contain mis-annotated CDS as evaluated by BLASTx against the NCBI nr database (accessed March 2017). Sequences were aligned using MUSCLE and the alignments were visualized in the CLC Main Workbench v.7 software (Qiagen, Aarhus, Denmark). Only substitutions for which the ancestral state could be determined unambiguously (conserved in at least 2 sequences, including in the Burkholderia sp. TSV86 genome) were considered.

Real-time PCR Assays

Real-time PCR assays were performed as described earlier (Novak et al., 2006; Price et al., 2012).

Fatty Acid Methyl Ester Analysis

After a 24 h incubation period at 28°C on Tryptone Soya Agar (BD), a loopful of well-grown cells was harvested and fatty acid methyl esters were prepared, separated and identified using the Microbial Identification System (Microbial ID) as described previously (Vandamme et al., 1992).

Biochemical Characterization

Biochemical characterization was performed as described previously (Henry et al., 2001).

MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry

MALDI-TOF MS was performed as described previously (De Bel et al., 2011) using a Microflex LT MALDI-TOF MS instrument (flexControl version 3.4, MALDI Biotyper Compass Explorer 4.1) with the reference database version 6.0.0.0 (6,903 database entries) (Bruker Daltonik).

Results and Discussion

Misidentification of Strain LMG 28154T

The identification of Gram-negative non-fermenting bacteria isolated from respiratory secretions of people with CF may prove challenging, not the least because the CF lung can harbor a range of opportunistic bacteria rarely seen in the general population. Many of these opportunists represent novel species whose correct diagnosis requires formal description. In the present study, we report genomic and basic taxonomic characteristics for the formal description of a rare but most unusual Burkholderia species that can colonize the CF lung. Preliminary biochemical characterization, including the observation of a typical slowly positive oxidase reaction, suggested this organism was a B. cepacia complex bacterium, yet amplification of the recA gene (Mahenthiralingam et al., 2000), a standard approach for the identification of B. cepacia complex bacteria, proved repeatedly negative (data not shown). Also, colonies of each of these isolates had a mucoid appearance on Columbia sheep’s blood agar, a characteristic that is rarely seen among B. cepacia complex bacteria. MALDI-TOF MS analysis yielded B. multivorans as best hit for each of the isolates. Score values of cell smears ranged between 1.66 and 1.87, with a difference of less than 0.2 toward the next species, suggesting this was a Burkholderia, but not providing species level identification (De Bel et al., 2011). Similarly, score values of cell extracts ranged between 1.61 and 1.96, again with a difference of less than 0.2 toward the next species. Initial partial 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis unexpectedly yielded B. pseudomallei and relatives as nearest neighbor species, rather than B. cepacia complex bacteria. While these isolates indeed were arginine dihydrolase positive, like B. pseudomallei and B. thailandensis, they did not reduce nitrate. The 266152 and type III secretion system based real-time PCR assays (Novak et al., 2006; Price et al., 2012) were negative, which excluded their identification as B. pseudomallei, B. thailandensis, B. humptydooensis or B. oklahomensis (data not shown). Adding to the confusion of this diagnostic problem, were the unusual dry sheen overlaying a slightly mucoid colony texture in one patient’s first culture (R-20802), while a subsequent culture (LMG 28154T) was as mucoid as commonly observed for Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates. In addition, the former culture looked mixed with small mucoid colonies and large mucoid colonies that exhibited different appearances but that yielded identical RAPD patterns (data not shown). This phenomenon, known as phenotypic switching, is commonly seen in pathogenic Burkholderia species (Chantratita et al., 2007; Bernier et al., 2008).

Strain LMG 28154T Represents a Novel Species in the B. pseudomallei Complex

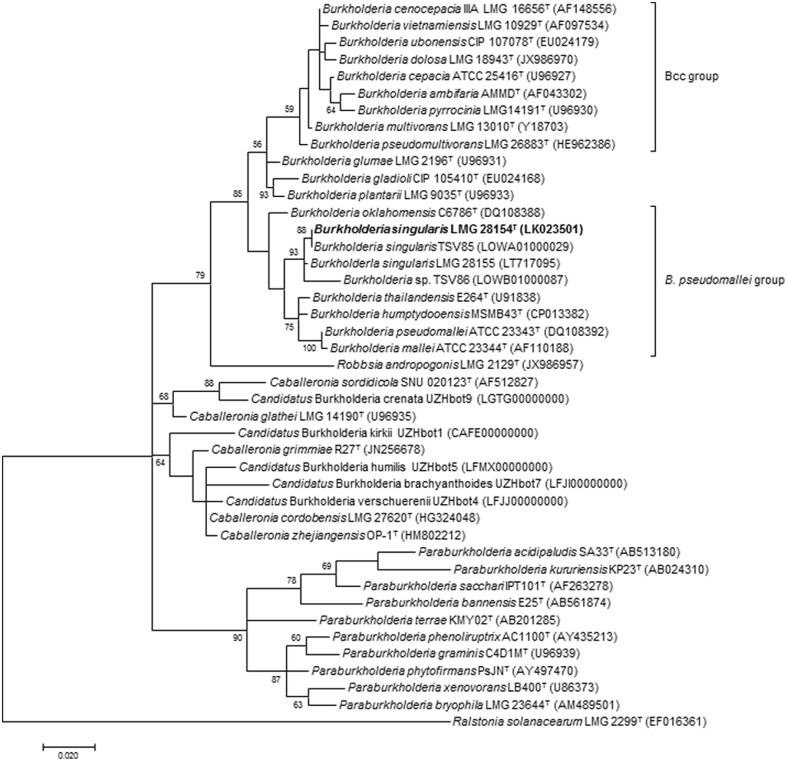

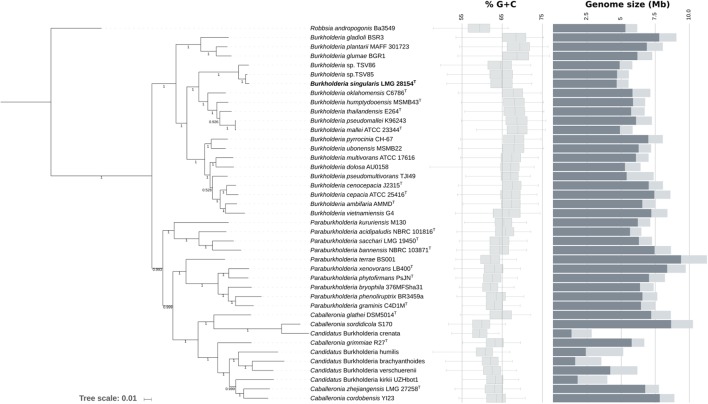

To clarify the taxonomic status of these isolates, the nearly complete 16S rRNA gene sequences of strains LMG 28154T and LMG 28155 were determined and proved nearly identical (99.3% pairwise identity). The similarity level of the 16S rRNA gene of strain LMG 28154T toward those of the type strains to the nearest phylogenetic neighbors was 98.97% (B. thailandensis), 98.55% (B. pseudomallei), 98.49% (B. mallei), 98.60% (B. humptydooensis) and 98.35% (B. oklahomensis) (Figure 1); type strains of B. cepacia complex species had ≤98.32% 16S rRNA gene sequence identity. A draft whole genome sequence of strain LMG 28154T was subsequently generated to further determine the degree of genomic relatedness of this novel bacterium with its nearest neighbor species. Genome assembly of strain LMG 28154T yielded 135 contigs and a total assembly size of 5.54 Mb, with an N50 of 83 kb and an average coverage of 70×. Annotation revealed 5268 CDS and 50 tRNAs coding for all amino acids. The rRNA operon was assembled into a single contig due to the use of short-span read libraries that prohibit the resolution of larger repeats, but coverage analysis indicated the presence of four copies of the rRNA operon in the genome consistent with the rRNA operon copy number in B. pseudomallei, B. thailandensis, B. humptydooensis and B. oklahomensis. The 5268 predicted CDS features had an average length of 894 bp and a coding density of 85%, which was within the normal range for free-living Burkholderia species (Figure 2). ANI values between strain LMG 28154T and its nearest phylogenetic neighbor species were below 85% (Supplementary Table S1), i.e., well below the commonly accepted threshold of 95–96% for species delineation (Richter and Rossello-Mora, 2009), confirming that strain LMG 28154T represents a novel Burkholderia species. Remarkably, ANI values between strain LMG 28154T and two water isolates (i.e., Burkholderia sp. TSV85 and Burkholderia sp. TSV86), whose whole genome sequences are publicly available, were 98.09 and 94.40, respectively, indicating that the former represents the same species. The water isolates were collected in 2010 from a single site (19°15′27.44″S; 146°47′36.20″E) in North Queensland, Australia, in a region endemic for B. pseudomallei. The ANI value of 94.40 for the latter strain is situated just below the species delineation threshold (Richter and Rossello-Mora, 2009), suggesting it represents a distinct, yet closely related novel Burkholderia species as revealed by its position in the 16S rRNA based phylogenetic tree (Figure 1). A phylogenetic analysis based on 15092 conserved nucleotide positions was subsequently performed to better reflect organismal phylogeny (Figure 2). This tree confirmed that the novel species represented by strain LMG 28154T occupies a very distinct position within the B. pseudomallei complex of the genus Burkholderia (Vandamme and Peeters, 2014; Price et al., 2016) and that Burkholderia sp. TSV86 is closely related to it.

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic tree based on nearly complete 16S rRNA gene sequences of Burkholderia representatives and B. singularis sp. nov. isolates. The optimal tree (highest log likelihood) was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura-Nei model in MEGA7 (Kumar et al., 2016). A discrete Gamma distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites [5 categories (+G, parameter = 0.3465)] and allowed for some sites to be evolutionarily invariable ([+I], 42.1434% sites). The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches if higher than 50%. The sequence of Ralstonia solanacearum LMG 2299T was used as outgroup. The scale bar indicates the number of substitutions per site. Taxonomic type strains are indicated by superscript T in strain numbers.

FIGURE 2.

Genomic phylogeny and characteristics of the genus Burkholderia. The phylogenetic tree was built using an alignment of 23 conserved single copy COGs and an approximate maximum-likelihood approach (see Materials and Methods for details). The %G+C distribution was calculated on non-overlapping 1 kb segments for each genome and plotted as box plots with extreme values removed for clarity. Total genome size (bar plot) is approximated by size of the assembly and coding content (dark gray) corresponds to the sum of the length of all annotated CDS features, discounting predicted pseudogenes. Shimodaira-Hasegawa-like local support values as given by the program Fasttree are indicated.

Standard biochemical identification of B. pseudomallei complex species is notoriously difficult (Glass et al., 2006). Yet, the present novel species can be distinguished from species in the B. pseudomallei complex through the absence of nitrate reduction and a mucoid appearance on Columbia sheep blood agar. In addition, its oxidase activity is typically slow as observed in B. cepacia complex species (Henry et al., 2001).

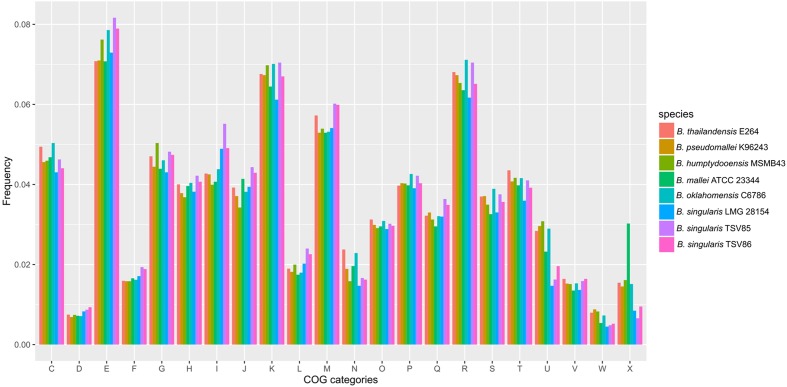

Functional Content of the LMG 28154T Genome

We compared the functional content of the LMG 28154T genome to that of closely related Burkholderia species in order to find differences in gene content related to lifestyle or pathogenicity. We compared the distribution of genes assigned to each major COG functional category for strains LMG 28154T, B. thailandensis E264T, B. pseudomallei K96243 and B. oklahomensis C6786T (Figure 3). The total number of genes with COG assignments was lower for strain LMG 28154T than for the other strains (4241 vs. 5019–5445), owing to an overall smaller genome. However, the functional profile of strain LMG 28154T was not significantly different from any of the other species (Pearson’s Chi squared p-value > 0.05), indicating that no specific functional category is enriched or reduced in strain LMG 28154T. Similarly, of the 5268 predicted CDS in the LMG 28154T genome, 3248 are part of the core genome of strains LMG 28154T, B. thailandensis E264T, B. pseudomallei K96243 and B. oklahomensis C6786T, with only 1668 genes without predicted orthologs in the other three genomes. Further analyses revealed that the core genome of strains B. thailandensis E264T, B. pseudomallei K96243 and B. oklahomensis C6786T possessed a dissimilatory nitrate reductase (BPSL2308 to BPSL2312 in the B. pseudomallei K96243 genome) that was lacking from the genome of LMG 28154T, as well as from strains TSV85 and TSV86 (Supplementary Table S2). This difference explains the lack of nitrate reduction observed in phenotypic assays and might affect survival of strain LMG 28154T under anaerobic conditions. Components of the cluster 1 Type VI secretion system (T6SS-1; BPSS1493–BPSS1512) are also missing in the LMG 28154T genome. Knock-out mutants in hcp1 (BPSS1498) are significantly less virulent in a Syrian hamster melioidosis model, with an LD50 more than 1000-fold higher than wild-type B. pseudomallei K96243 (Burtnick et al., 2011). The lack of this critical virulence factor might thus be responsible for attenuated pathogenicity of strain LMG 28154T. Finally, a putative wza and wzc-dependent exopolysaccharide gene cluster is encoded by genes BSIN_4472–4480, and does not have putative orthologs in the genomes of B. thailandensis E264T, B. pseudomallei K96243 and B. oklahomensis C6786T. The BSIN_4472–4480 genes are conserved with more than 95% identity at the nucleotide level in strains TSV85 and TSV86 (locus tags WS67_RS02485–02520 and WS68_RS24380–24415, respectively). Instead, predicted proteins of the gene cluster show high similarity, ranging from 45 to 70% identity, to a syntenic gene cluster of B. cenocepacia J2315T (Supplementary Figure S5). B. cenocepacia produces several uncharacterized exopolysaccharides in addition to cepacian, the main exopolysaccharide of B. cenocepacia (Holden et al., 2009). However, some of these cryptic exopolysaccharide cluster genes are important for biofilm formation (Fazli et al., 2013), and the presence of this gene cluster in strain LMG 28154T may explain in part its unusual mucoid appearance.

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of genes in COG functional categories. Frequencies of genes in COG categories of selected Burkholderia genomes. The values represent the number of genes in COG categories, divided by the total number of genes with a COG assignment (genes without COG assignments are not counted for clarity). (C) = Energy production and conversion, (D) = Cell cycle control, cell division, chromosome partitioning, (E) = Amino acid transport and metabolism, (F) = Nucleotide transport and metabolism, (G) = Carbohydrate transport and metabolism, (H) = Coenzyme transport and metabolism, (I) = Lipid transport and metabolism, (J) = Translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis, (K) = Transcription, (L) = Replication, recombination and repair, (M) = Cell wall/membrane/envelope biogenesis, (N) = Cell motility, (O) = Posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones, (P) = Inorganic ion transport and metabolism, (Q) = Secondary metabolites biosynthesis, transport and catabolism, (R) = General function prediction only, (S) = Function unknown, (T) = Signal transduction mechanisms, (U) = Intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport, (V) = Defense mechanisms, (W) = Extracellular structures, (X) = mobilome.

Genome Wide AT Bias in Strain LMG 28154T

The average mol% G+C from in silico analysis of the strain LMG 28154T genome sequence data was 64.34%. This value falls below the range of 65.7–68.5% for the genus Burkholderia as defined by Sawana et al. (2014) and within the 58.9–65.0% and 59.0–65.0% range for the newly described genera Paraburkholderia and Caballeronia, respectively (Dobritsa and Samadpour, 2016). The base composition of genomic sequences is highly variable across species and features prominently in descriptions of bacterial species (Tindall et al., 2010). It was one of two criteria (the other being the presence of conserved indels) that supported the first subdivision of the genus Burkholderia (Sawana et al., 2014), i.e., the separation of the species presently included in the genus Burkholderia sensu stricto from those are that presently classified in the genera Paraburkholderia, Caballeronia, and Robbsia. Because the presence of non-homologous regions with different average %G+C may explain the deviation of strain LMG 28154T from related species, we measured the distribution of %G+C in 1 kb segments across the entire genome of representative Burkholderia, Paraburkholderia, Caballeronia and Robbsia species (Figure 2). The median %G+C of strain LMG 28154T was 64.9%, indicating that extreme values are not responsible for the low average %G+C of the species. To estimate the %G+C on conserved sections of the genome, we also calculated the average %G+C of 2081 single-copy orthologous genes computed between strains LMG 28154T, B. thailandensis E264T, B. pseudomallei K96243, B. oklahomensis C6786T and B. glumae BGR1 (Supplementary Figure S1). Overall, genes of LMG 28154T displayed an average %G+C of 65.45%, below the averages of 67.74–68.81% for orthologs belonging to reference Burkholderia species. Moreover, the %G+C of orthologous genes belonging to strain LMG 28154T were on average 2.53% lower than in B. pseudomallei K96243 (Paired Student’s t-test p < 0.001), 2.30% lower than in B. thailandensis E264T (p < 0.001) and 3.36% lower than in B. glumae BGR1 (p < 0.001). This effect was exacerbated at the third codon positions, with a difference in average %G+C in LMG 28154T compared to other species ranging from 6.15 to 7.81% (Supplementary Figure S1). Moreover, fourfold degenerate sites, which are not expected to be under selection for protein functionality, were significantly richer in AT in strain LMG 28254T (Wilcoxon signed rank test p < 0.001) than in related species (Supplementary Figure S2). Similarly, the analysis of substitutions in a randomly chosen set of 17 intergenic regions revealed an AT mutational bias (ratio of GC > AT over AT > GC substitutions = 1.35, n = 87, data not shown). This value was significantly higher than the AT bias of 0.81 (binomial test p < 0.05) measured by Dillon et al. (2015). Together, these data are indicative of a pervasive, genome-wide AT-bias affecting strain LMG 28154T.

Frequency of Recombination and Its Impact on GC-Biased Gene Conversion in Strain LMG 28154T

GC-biased gene conversion (gBGC), a process which drives the evolution of G+C content in mammals by favoring the conversion of GC-rich intermediates of recombination (Duret and Galtier, 2009), has recently been proposed to act in prokaryotes as well (Lassalle et al., 2015). We reasoned that if gBGC also influences average %G+C in Burkholderia species, species or genes that experience less recombination (for example due to ecological isolation) would have a lower average %G+C. We computed orthologous gene sets of strain LMG 28154T, B. thailandensis E264T, B. pseudomallei K96243, B. oklahomensis C6786T, Burkholderia sp. TSV86 and B. glumae BGR1 and calculated the probability of recombination for each ortholog set (see Materials and Methods) and evaluated if genes with high probability of recombination (n = 193) had higher %G+C than genes without (n = 1866). We did not find any statistically significant increase in average %G+C at the third codon position (which we showed above displayed the largest effect) in orthologous sets which showed evidence of recombination (Student’s t-test p = 0.387, data not shown). This is in accordance with the recent results of Lassalle et al. (2015) who did not find evidence that recombination was affecting %G+C of core genes of some species of the B. cepacia complex and the B. pseudomallei complex, in contrast to most bacterial species. Our method likely underestimated the number of genes subject to recombination because of the small genome dataset and our focus on single copy orthologs conserved in all genomes. However, because recombination is rare (<2%) in the core genome of species of the B. pseudomallei complex (Lassalle et al., 2015), our statistical analysis gives sufficient power to reject the hypothesis that gBGC contributes to the low %G+C of strain LMG 28154T. The lower average %G+C of strain LMG 28154T is therefore not a result of a lower frequency of recombination and its impact on gBGC.

No Reductive Genome Evolution in Strain LMG 28154T

Pervasive GC > AT mutation bias is a hallmark of reductive genome evolution, a phenomenon affecting intracellular pathogens as well as obligate symbionts with reduced effective population sizes (Moran, 2002), including some candidate Burkholderia species that cluster into the genus Caballeronia (Carlier et al., 2016; Pinto-Carbo et al., 2016). Other signs of reductive genome evolution include a significantly smaller genome size (Moran, 2002), an abundance of pseudogenes and insertion elements (Andersson and Andersson, 2001) and relaxed purifying selection (Kuo et al., 2009) compared to free-living relatives. B. pseudomallei, B. oklahomensis and B. thailandensis are environmentally acquired pathogens with the ability to replicate intracellularly inside macrophages (Wand et al., 2011; Willcocks et al., 2016). This raises the possibility that strain LMG 28154T represents a lineage that transitioned to an exclusive host-associated lifestyle, thereby suffering from transmission bottlenecks. The genome of strain LMG 28154T is slightly smaller than that of immediate free-living relatives, but still within the range of free-living Burkholderia (Figure 2). We identified only 57 potential pseudogenes in the genome of strain LMG 28154T, which amount to a total of 42.2 kb (0.76% of the genome), for a total coding capacity of the genome of 85%, which was also within the range of free-living Burkholderia species. The genome encodes 49 predicted proteins belonging to the COG category X (mobilome), which includes phage-derived proteins, transposases and other mobilome components (Galperin et al., 2015). This is again less than what has been reported for Caballeronia species in intermediate stages of reductive genome evolution (Lackner et al., 2011; Carlier and Eberl, 2012; Carlier et al., 2016; Pinto-Carbo et al., 2016). The most universal (but not exclusive) sign of ongoing reductive genome evolution is a relaxation of purifying selection, which results from an increased level of genetic drift experienced by recurrent population bottlenecks (Kuo et al., 2009). We therefore measured the ratios of non-synonymous to synonymous mutations (dN/dS ratio) of a set of 2890 orthologous genes which did not show evidence of recombination between the strains LMG 28154T, TSV86, B. oklahomensis C6786T and B. pseudomallei K96243, to estimate the levels of genetic drift experienced by strains of the first pair of species on one hand, and other species of the B. pseudomallei complex on the other hand. We chose these sets of genomes because they presented comparable levels of sequence divergence (dS) and represent species with similar ecology. The average genome-wide dN/dS ratio between strains LMG 28154T and TSV86 (dN/dS = 0.076) is indicative of relatively strong purifying selection and is consistent with a free-living or facultative lifestyle (Novichkov et al., 2009). Moreover, the genome-wide distribution of dN/dS values of LMG 28154T /TSV86 showed only a slight upward shift compared to ortholog pairs in B. pseudomallei K96243/B. oklahomensis C6786T (average dN/dS = 0.065) (Supplementary Figure S3). This indicates that purifying selection is not drastically relaxed in the novel taxon lineage compared to the B. pseudomallei – B. oklahomensis lineage. An analysis including the pair B. oklahomensis C6786T and B. thailandensis E264T showed similar results with genome-wide dN/dS = 0.066. It is possible that %G+C changes and altered codon usage bias in the LMG 28154T genome affects the rate of evolution of synonymous sites, and in this case, the dN/dS ratio reported for the pair of strains LMG 28154T/TSV86 would in fact overestimate the intensity of purifying selection. However, we argue that the small difference in codon preference observed is unlikely to have arisen from selection for optimal codon usage given the similar translation machinery (e.g., number of tRNAs) in the species compared. The lack of evidence for rampant pseudogenization or IS proliferation, together with effective purifying selection and high coding density lead us to conclude that reductive genome evolution is not responsible for the genome-wide AT-bias in strain LMG 28154T.

Functions Related to DNA Repair and Metabolism in Strain LMG 28154T

Contrary to what has been documented for most bacterial species, Dillon et al. (2015) recently reported that the mutational landscape in Burkholderia species is biased toward AT > GC substitutions. Historically, differences in mutation patterns have been thought to be the primary reason for the variation in %G+C in bacterial genomes (Sueoka, 1961), although more recent evidence suggested that selective forces also influence nucleotide composition, including in Burkholderia species (Balbi et al., 2009; Hershberg and Petrov, 2010; Dillon et al., 2015). To identify functions related to DNA repair and metabolism that were missing or altered in strain LMG 28154T compared to close relatives with high %G+C, we computed the core genome of strains B. oklahomensis C6786T, B. pseudomallei K96243 and B. thailandensis E264T, and compared the COG functional assignments to the proteome of strain LMG 28154T. We found only 2 genes (locus tags: BPSL1022 and BPSS0452) with a COG functional assignment falling into the L category (DNA replication and repair) in the core genome of B. pseudomallei K96243 that did not have any putative orthologs in the genome of strain LMG 28154T. BPSL1022 possesses a GIY-YIG domain found in the endonuclease SLX1 family, but the function of this enzyme in DNA repair or metabolism is unknown. BPSS0452 is a putative DNA polymerase/3′-5′ exonuclease of the PolX family, which may play a role in the base excision repair (BER) pathway (Banos et al., 2008; Khairnar and Misra, 2009). BLASTp analysis reveals that close homologs of BPSS0452 are conserved in various Burkholderia species but are notably absent from B. mallei, B. glumae and B. gladioli strains (Supplementary Figure S4). These species all have average genomic %G+C > 68.5%, indicating that loss of the PolX function is unlikely to be solely responsible for the altered %G+C of strain LMG 28154T. However, BSIN_0972, which encodes a putative DNA-3-methyladenine glycosylase 1 of the TagI family, is a pseudogene in strain LMG 28154T (and also in TSV86). TagI proteins catalyze the excision of alkylated adenine and guanidine bases from DNA as part of the BER pathway (Bjelland and Seeberg, 1987). Instead, BSIN_4945 encodes a protein of the same superfamily (COG2818) with 47% identity to the product of BSIN_0972, but this gene has no close homologs in Burkholderia species outside of strains TSV85 and TSV86 (Supplementary Figure S4). This gene was possibly acquired via horizontal gene transfer, since the closest homologs in the NCBI nr database belong to bacteria only distantly related to Burkholderia (closest hit in the genome of Cohnella sp. OV330 with 78% identity at the protein level, followed by Noviherbaspirillum massiliense JC206 with 77% identity). Because the putative ortholog of BSIN_0972 still seems functional in strain TSV85, and orthologs of BSIN_4945 are present in strains LMG 28154T, TSV85 and TSV86, acquisition of the alternative DNA-3-methyladenine glycosylase 1 encoded by BSIN_4945 preceded the mutation events leading to the loss of the ancestral tag gene in the novel taxon lineage. Altered regulation of components of the BER pathway, or different affinity for alkylated purines could perhaps explain a bias in DNA composition in these bacteria.

The Subdivision of the Genus Burkholderia sensu lato into the Genera Burkholderia sensu stricto, Paraburkholderia and Caballeronia Is Not Based on Solid Biological Evidence

Comparative 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis provided a phylogenetic image of the genus Burkholderia sensu lato that consisted of several main lineages and species that represented unique lines of descent (Gyaneshwar et al., 2011; Suarez-Moreno et al., 2012; Estrada-de los Santos et al., 2013). Depoorter et al. (2016) recently presented a comprehensive overview of the main species clusters and single species representing unique lines of descent within this genus. Although the value of the 16S rRNA gene as a single-gene marker for bacterial phylogeny is unsurpassed, it is well-known that its resolution for resolving organismal phylogeny has several limitations (Dagan and Martin, 2006), and branching levels in 16S rRNA based trees of Burkholderia species are commonly not supported by high bootstrap values. Yet, Sawana et al. (2014) used 16S rRNA gene sequence divergence as the basis to reclassify a large number of Burkholderia species into the novel genus Paraburkholderia. Species retained in the genus Burkholderia were further characterized by a % G+C content of 65.7–68.5%, and shared six conserved sequence indels, while all other Burkholderia strains examined had a % G+C content of 61.4–65.0% and shared two conserved sequence indels; all the latter species were reclassified into the novel genus Paraburkholderia. Very rapidly, the classification of Paraburkholderia species was revisited by Dobritsa and Samadpour (2016) and part of the Paraburkholderia species were further reclassified into the novel genus Caballeronia. The latter species clustered again together in a 16S rRNA based phylogenetic tree and shared five conserved sequence indels. More recently, Paraburkholderia andropogonis, one of the species that consistently forms a unique line of 16S rRNA descent, was further reclassified into the novel genus Robbsia; the G+C content of its type strain is 58.92 mol % (Lopes-Santos et al., 2017).

The availability of numerous whole-genome sequences nowadays presents ample opportunities for phylogenomic studies to generate multi-gene based phylogenetic trees with superior stability and that better reflect organismal phylogeny (Yutin et al., 2012; Wang and Wu, 2013). However, it has been argued that bootstrap and similar support values increase with the increasing number of sites sampled (Phillips et al., 2004) such that a high bootstrap proportion for a multi-gene concatenated phylogeny does not necessarily mean that the tree is thus likely to be correct (Thiergart et al., 2014). The phylogenomic tree presented in the present study (Figure 2) is based on 15092 conserved nucleotide positions from 21 nearly universal, single copy gene markers and shows that Caballeronia and Paraburkholderia species represent a single, mixed and heterogeneous lineage, as do species retained in the genus Burkholderia sensu stricto. In contrast, R. andropogonis, the sole member of the genus Robbsia, continued to form a well-separated branch below the Burkholderia- Paraburkholderia- Caballeronia cluster (Figure 2). We obtained very similar results earlier (Depoorter et al., 2016) through analysis of 53 ribosomal protein-encoding genes (Jolley et al., 2012), while a recent phylogenomic study based on the analysis of 106 conserved protein sequences revealed distinct and stable clusters for each of the genera Burkholderia sensu stricto, Caballeronia and Paraburkholderia (Beukes et al., 2017).

Although G+C content long appeared to discriminate between Burkholderia sensu stricto and other Burkholderia species, the data presented above for strain LMG 28154T demonstrated that there is an overlapping continuum in G+C content of Burkholderia sensu stricto species and other species previously classified within this genus. Finally, the sole remaining criterion that discriminated between Burkholderia sensu stricto and other Burkholderia species, is the presence of six conserved sequence indels (Sawana et al., 2014). Burkholderia are multi-chromosome bacteria and the latter six genes are located on chromosome 2 in most species. The latter chromosome is highly dynamic in Burkholderia species (Cooper et al., 2010) and none of the genes (i.e., BCAM2774, BCAM0964, BCAM0057, BCAM0941, BCAM2347, and BCAM2389) containing the indels appeared essential for growth on either rich or minimal media (Wong et al., 2016). Together, these data demonstrate that there is no solid biological evidence for the ongoing taxonomic dissection of the genus Burkholderia. In our opinion, the proposals of the genera Caballeronia and Paraburkholderia are ill-founded. Researchers, referees and editors of scientific journals should be aware that the rules of bacterial nomenclature stipulate that names that were validly published remain valid, regardless of subsequent reclassifications (Parker et al., 2017). Authors can therefore continue to work with the original (Burkholderia) species names as these were all validly published, and focus their efforts on the understanding of the biology of these fascinating bacteria.

Conclusion

The genotypic and phenotypic distinctiveness of strain LMG 28154T warrants its classification as a novel species within the B. pseudomallei complex (Depoorter et al., 2016; Price et al., 2016) of the genus Burkholderia. B. cepacia complex MLST analysis revealed that the isolates R-20802 and R-50762 have the same allelic profile (ST-813) as strain LMG 28154T, and therefore represent the same strain that persisted in this Canadian CF patient. Strain LMG 28155 represents a second sequence type (ST-815) that differs in six out of seven alleles (i.e., in 17 nucleotides of a total of 2773 nucleotide positions) examined. Finally, extraction of the MLST loci from the genome sequence of strain TSV85 and the ANI values discussed above (Supplementary Table S1), demonstrated that it represents a third ST, i.e., ST-1295 that also differs in six out of seven alleles from the other STs in this species. This novel species has been recovered from human or environmental samples on three continents. It has a unique MALDI-TOF MS profile and displays several differential phenotypic characteristics that will facilitate its identification in diagnostic laboratories. We propose to formally classify this novel species as B. singularis sp. nov. with strain LMG 28154T as the type strain. The same strain was recently isolated again from the same patient (data not shown) but colonies unexpectedly were non-mucoid on Columbia sheep blood agar. Together, this type strain has been isolated from the same Canadian CF patient over the course of 14 years, indicating that in this case at least, the clinical impact of this species has been relatively mild.

Description of Burkholderia singularis sp. nov.

Burkholderia singularis (sin.gu’la.ris. L. adj. singularis, singular, remarkable, unusual)

Cells are Gram-negative, non-sporulating rods. All strains grow on Columbia sheep blood agar, B. cepacia Selective agar, Yeast Extract Mannitol agar and MacConkey agar. Mucoid growth and no hemolysis on Columbia sheep blood agar. Growth is observed at 42°C. Motility is strain dependent. No pigment production. Oxidase activity is slowly positive. No lysine or ornithine decarboxylase activity. Activity of β-galactosidase is present but no nitrate reduction (both as determined using the API 20NE microtest system). Gelatin liquefaction and esculin hydrolysis are strain-dependent. Acidification of glucose, maltose, lactose and xylose but not sucrose; strain-dependent reactions for acidification of adonitol. The following fatty acids are present in major amounts: C16:0, C16:0 3-OH, C18:1 ω7c and summed features 2 and 3; C14:0, C16:0 2-OH, C16:1 2-OH, C17:0 cyclo, and C18:1 2OH are present in moderate amounts. Strains in the present study have been isolated from human respiratory specimens and a water sample.

The type strain is LMG 28154T (= CCUG 65685T). It does not liquefy gelatin, hydrolyse esculin and is non-motile; it acidifies adonitol. Other phenotypic characteristics are as described for the species. Its G+C content is 64.34%.

Accession Numbers

The GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession numbers for the 16S rRNA gene sequences of strains LMG 28154T and LMG 28155 are LK023501 and LT717095, respectively. The accession numbers for the LMG 28154T genome are FXAN01000001-FXAN01000135.

Author Contributions

PV and AC conceived the study and wrote the manuscript. JZ, MM, JW, and BC contributed to conceptualization. AC, EP, and DS carried out the genomic data analyses. CP and BDS analyzed the 16S rRNA and MLST data and performed phylogenetic analyses. CP, BDS, EP, DS, DH, TH, and AB carried out wet-lab microbiological analyses. PV, JZ, MM, JW, and BC generated the required funding. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

JZ would like to acknowledge David Speert for his provision of laboratory space and operating funds as well as Ms. Rebecca Hickman for expert technical assistance.

Funding. The Menzies School of Health work was supported by grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, including project grants 1098337 and 1131932 (the HOT NORTH initiative).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01679/full#supplementary-material

TABLE S1 | ANI values between strain LMG 28154T and phylogenetically neighboring species.

TABLE S2 | Functions from the core genome of strains B. thailandensis E264T, B. pseudomallei K96243 and B. oklahomensis C6786T lacking from the genome of LMG 28154T.

References

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215 403–410. 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schaffer A. A., Zhang J. H., Zhang Z., Miller W., et al. (1997). Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 3389–3402. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson J. O., Andersson S. G. E. (2001). Pseudogenes, junk DNA, and the dynamics of Rickettsia genomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18 829–839. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz R. K., Bartels D., Best A. A., Dejongh M., Disz T., Edwards R. A., et al. (2008). The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9:75 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balbi K. J., Rocha E. P. C., Feil E. J. (2009). The temporal dynamics of slightly deleterious mutations in Escherichia coli and Shigella spp. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26 345–355. 10.1093/molbev/msn252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin A., Mahenthiralingam E., Drevinek P., Vandamme P., Govan J. R., Waine D. J., et al. (2007). Environmental Burkholderia cepacia complex isolates in human infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13 458–461. 10.3201/eid1303.060403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A. A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A. S., et al. (2012). SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19 455–477. 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banos B., Lazaro J. M., Villar L., Salas M., De Vega M. (2008). Editing of misaligned 3 ′-termini by an intrinsic 3 ′-5 ′ exonuclease activity residing in the PHP domain of a family X DNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 36 5736–5749. 10.1093/nar/gkn526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier S. P., Nguyen D. T., Sokol P. A. (2008). A LysR-type transcriptional regulator in Burkholderia cenocepacia influences colony morphology and virulence. Infect. Immun. 76 38–47. 10.1128/IAI.00874-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beukes C. W., Palmer M., Manyaka P., Chan W. Y., Avontuur J. R., Van Zyl E., et al. (2017). Genome data provides high support for generic boundaries in Burkholderia sensu lato. Front. Microbiol. 8:1154 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelland S., Seeberg E. (1987). Purification and characterization of 3-methyladenine DNA glycosylase I from Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 15 2787–2801. 10.1093/nar/15.7.2787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A. M., Lohse M., Usadel B. (2014). Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30 2114–2120. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruen T. C., Philippe H., Bryant D. (2006). A simple and robust statistical test for detecting the presence of recombination. Genetics 172 2665–2681. 10.1534/genetics.105.048975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtnick M. N., Brett P. J., Harding S. V., Ngugi S. A., Ribot W. J., Chantratita N., et al. (2011). The cluster 1 type VI secretion system is a major virulence determinant in Burkholderia pseudomallei. Infect. Immun. 79 1512–1525. 10.1128/IAI.01218-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capella-Gutierrez S., Silla-Martinez J. M., Gabaldon T. (2009). trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25 1972–1973. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlier A., Fehr L., Pinto-Carbo M., Schaberle T., Reher R., Dessein S., et al. (2016). The genome analysis of Candidatus Burkholderia crenata reveals that secondary metabolism may be a key function of the Ardisia crenata leaf nodule symbiosis. Environ. Microbiol. 18 2507–2522. 10.1111/1462-2920.13184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlier A. L., Eberl L. (2012). The eroded genome of a Psychotria leaf symbiont: hypotheses about lifestyle and interactions with its plant host. Environ. Microbiol. 14 2757–2769. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02763.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver T., Berriman M., Tivey A., Patel C., Bohme U., Barrell B. G., et al. (2008). Artemis and ACT: viewing, annotating and comparing sequences stored in a relational database. Bioinformatics 24 2672–2676. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantratita N., Wuthiekanun V., Boonbumrung K., Tiyawisutsri R., Vesaratchavest M., Limmathurotsakul D., et al. (2007). Biological relevance of colony morphology and phenotypic switching by Burkholderia pseudomallei. J. Bacteriol. 189 807–817. 10.1128/JB.01258-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cock P. J. A., Antao T., Chang J. T., Chapman B. A., Cox C. J., Dalke A., et al. (2009). Biopython: freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 25 1422–1423. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenye T., Vandamme P. (2003). Diversity and significance of Burkholderia species occupying diverse ecological niches. Environ. Microbiol. 5 719–729. 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00471.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compant S., Nowak J., Coenye T., Clement C., Barka E. A. (2008). Diversity and occurrence of Burkholderia spp. in the natural environment. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32 607–626. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper V. S., Vohr S. H., Wrocklage S. C., Hatcher P. J. (2010). Why genes evolve faster on secondary chromosomes in bacteria. PLoS Comput. Biol. 6:e1000732 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie B. J., Gal D., Mayo M., Ward L., Godoy D., Spratt B. G., et al. (2007). Using BOX-PCR to exclude a clonal outbreak of melioidosis. BMC Infect. Dis. 7:68 10.1186/1471-2334-7-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagan T., Martin W. (2006). The tree of one percent. Genome Biol. 7 118 10.1186/gb-2006-7-10-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bel A., Wybo I., Vandoorslaer K., Rosseel P., Lauwers S., Pierard D. (2011). Acceptance criteria for identification results of Gram-negative rods by mass spectrometry. J. Med. Microbiol. 60 684–686. 10.1099/jmm.0.023184-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depoorter E., Bull M. J., Peeters C., Coenye T., Vandamme P., Mahenthiralingam E. (2016). Burkholderia: an update on taxonomy and biotechnological potential as antibiotic producers. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100 5215–5229. 10.1007/s00253-016-7520-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon M. M., Sung W., Lynch M., Cooper V. S. (2015). The rate and molecular spectrum of spontaneous mutations in the GC-rich multichromosome genome of Burkholderia cenocepacia. Genetics 200 935–946. 10.1534/genetics.115.176834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobritsa A. P., Samadpour M. (2016). Transfer of eleven species of the genus Burkholderia to the genus Paraburkholderia and proposal of Caballeronia gen. nov to accommodate twelve species of the genera Burkholderia and Paraburkholderia. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 66 2836–2846. 10.1099/ijsem.0.001065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duret L., Galtier N. (2009). Biased gene conversion and the evolution of mammalian genomic landscapes. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 10 285–311. 10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-150001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 1792–1797. 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-de los Santos P., Vinuesa P., Martinez-Aguilar L., Hirsch A. M., Caballero-Mellado J. (2013). Phylogenetic analysis of Burkholderia species by multilocus sequence analysis. Curr. Microbiol. 67 51–60. 10.1007/s00284-013-0330-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazli M., Mccarthy Y., Givskov M., Ryan R. P., Tolker-Nielsen T. (2013). The exopolysaccharide gene cluster Bcam1330-Bcam1341 is involved in Burkholderia cenocepacia biofilm formation, and its expression is regulated by c-di-GMP and Bcam1349. Microbiologyopen 2 105–122. 10.1002/mbo3.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galperin M. Y., Makarova K. S., Wolf Y. I., Koonin E. V. (2015). Expanded microbial genome coverage and improved protein family annotation in the COG database. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 D261–D269. 10.1093/nar/gku1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudoux P. (2013). Pgirmess: Data Analysis in Ecology. R Package Version 1.5.2. Available at: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pgirmess [Google Scholar]

- Glass M. B., Steigerwalt A. G., Jordan J. G., Wilkins P. P., Gee J. E. (2006). Burkholderia oklahomensis sp. nov., a Burkholderia pseudomallei-like species formerly known as the Oklahoma strain of Pseudomonas pseudomallei. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 56 2171–2176. 10.1099/ijs.0.63991-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goris J., Konstantinidis K. T., Klappenbach J. A., Coenye T., Vandamme P., Tiedje J. M. (2007). DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57 81–91. 10.1099/ijs.0.64483-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich A., Saveliev V., Vyahhi N., Tesler G. (2013). QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29 1072–1075. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyaneshwar P., Hirsch A. M., Moulin L., Chen W. M., Elliott G. N., Bontemps C., et al. (2011). Legume-nodulating betaproteobacteria: diversity, host range, and future prospects. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 24 1276–1288. 10.1094/MPMI-06-11-0172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry D. A., Mahenthiralingam E., Vandamme P., Coenye T., Speert D. P. (2001). Phenotypic methods for determining genomovar status of the Burkholderia cepacia complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39 1073–1078. 10.1128/JCM.39.3.1073-1078.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberg R., Petrov D. A. (2010). Evidence that mutation is universally biased towards AT in bacteria. PLoS Genet. 6:e1001115 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden M. T. G., Seth-Smith H. M. B., Crossman L. C., Sebaihia M., Bentley S. D., Cerdeno-Tarraga A. M., et al. (2009). The genome of Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315 an epidemic pathogen of cystic fibrosis patients. J. Bacteriol. 191 261–277. 10.1128/JB.01230-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley K. A., Bliss C. M., Bennett J. S., Bratcher H. B., Brehony C., Colles F. M., et al. (2012). Ribosomal multilocus sequence typing: universal characterization of bacteria from domain to strain. Microbiology 158 1005–1015. 10.1099/mic.0.055459-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley K. A., Chan M. S., Maiden M. C. J. (2004). mlstdbNet - distributed multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) databases. BMC Bioinformatics 5:86 10.1186/1471-2105-5-86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolley K. A., Maiden M. C. J. (2010). BIGSdb: scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics 11:595 10.1186/1471-2105-11-595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khairnar N. P., Misra H. S. (2009). DNA polymerase X from Deinococcus radiodurans implicated in bacterial tolerance to DNA damage is characterized as a short patch base excision repair polymerase. Microbiology 155 3005–3014. 10.1099/mic.0.029223-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. (2016). MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C. H., Moran N. A., Ochman H. (2009). The consequences of genetic drift for bacterial genome complexity. Genome Res. 19 1450–1454. 10.1101/gr.091785.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner G., Moebius N., Partida-Martinez L., Hertweck C. (2011). Complete genome sequence of Burkholderia rhizoxinica, an endosymbiont of Rhizopus microsporus. J. Bacteriol. 193 783–784. 10.1128/JB.01318-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassalle F., Perian S., Bataillon T., Nesme X., Duret L., Daubin V. (2015). GC-content evolution in bacterial genomes: the biased gene conversion hypothesis expands. PLoS Genet. 11:e1004941 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letunic I., Bork P. (2016). Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v3: an online tool for the display and annotation of phylogenetic and other trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 W242–W245. 10.1093/nar/gkw290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Stoeckert C. J., Jr., Roos D. S. (2003). OrthoMCL: identification of ortholog groups for eukaryotic genomes. Genome Res. 13 2178–2189. 10.1101/gr.1224503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipuma J. J. (2010). The changing microbial epidemiology in cystic fibrosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23 299–323. 10.1128/CMR.00068-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes-Santos L., Castro D. B., Ferreira-Tonin M., Corrêa D. B., Weir B. S., Park D., et al. (2017). Reassessment of the taxonomic position of Burkholderia andropogonis and description of Robbsia andropogonis gen. nov., comb. nov. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 110 727–736. 10.1007/s10482-017-0842-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahenthiralingam E., Baldwin A., Dowson C. G. (2008). Burkholderia cepacia complex bacteria: opportunistic pathogens with important natural biology. J. Appl. Microbiol. 104 1539–1551. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03706.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahenthiralingam E., Bischof J., Byrne S. K., Radomski C., Davies J. E., Av-Gay Y., et al. (2000). DNA-based diagnostic approaches for identification of Burkholderia cepacia complex, Burkholderia vietnamiensis, Burkholderia multivorans, Burkholderia stabilis, and Burkholderia cepacia genomovars I and III. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38 3165–3173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran N. A. (2002). Microbial minimalism: genome reduction in bacterial pathogens. Cell 108 583–586. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00665-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notredame C., Higgins D. G., Heringa J. (2000). T-Coffee: a novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J. Mol. Biol. 302 205–217. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak R. T., Glass M. B., Gee J. E., Gal D., Mayo M. J., Currie B. J., et al. (2006). Development and evaluation of a real-time PCR assay targeting the type III secretion system of Burkholderia pseudomallei. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44 85–90. 10.1128/JCM.44.1.85-90.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novichkov P. S., Wolf Y. I., Dubchak I., Koonin E. V. (2009). Trends in prokaryotic evolution revealed by comparison of closely related bacterial and archaeal genomes. J. Bacteriol. 191 65–73. 10.1128/JB.01237-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Carroll M. R., Kidd T. J., Coulter C., Smith H. V., Rose B. R., Harbour C., et al. (2003). Burkholderia pseudomallei: another emerging pathogen in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 58 1087–1091. 10.1136/thorax.58.12.1087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker C. T., Tindall B. J., Garrity G. M. (2017). International code of nomenclature of prokaryotes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 10.1099/ijsem.1090.000778 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkins M. D., Floto R. A. (2015). Emerging bacterial pathogens and changing concepts of bacterial pathogenesis in cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 14 293–304. 10.1016/j.jcf.2015.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson W. R. (2000). Flexible sequence similarity searching with the FASTA3 program package. Methods Mol. Biol. 132 185–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters C., Zlosnik J. E., Spilker T., Hird T. J., Lipuma J. J., Vandamme P. (2013). Burkholderia pseudomultivorans sp. nov., a novel Burkholderia cepacia complex species from human respiratory samples and the rhizosphere. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 36 483–489. 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips M. J., Delsuc F., Penny D. (2004). Genome-scale phylogeny and the detection of systematic biases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21 1455–1458. 10.1093/molbev/msh137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto-Carbo M., Sieber S., Dessein S., Wicker T., Verstraete B., Gademann K., et al. (2016). Evidence of horizontal gene transfer between obligate leaf nodule symbionts. ISME J. 10 2092–2105. 10.1038/ismej.2016.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price E. P., Dale J. L., Cook J. M., Sarovich D. S., Seymour M. L., Ginther J. L., et al. (2012). Development and validation of Burkholderia pseudomallei-specific real-time PCR assays for clinical, environmental or forensic detection applications. PLoS ONE 7:e37723 10.1371/journal.pone.0037723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price E. P., Machunter B., Spratt B. G., Wagner D. M., Currie B. J., Sarovich D. S. (2016). Improved multilocus sequence typing of Burkholderia pseudomallei and closely related species. J. Med. Microbiol. 65 992–997. 10.1099/jmm.0.000312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price M. N., Dehal P. S., Arkin A. P. (2010). FastTree 2-approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE 5:e9490 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruesse E., Peplies J., Gloeckner F. O. (2012). SINA: accurate high-throughput multiple sequence alignment of ribosomal RNA genes. Bioinformatics 28 1823–1829. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice P., Longden I., Bleasby A. (2000). EMBOSS: the European molecular biology open software suite. Trends Genet. 16 276–277. 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02024-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter M., Rossello-Mora R. (2009). Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 19126–19131. 10.1073/pnas.0906412106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawana A., Adeolu M., Gupta R. S. (2014). Molecular signatures and phylogenomic analysis of the genus Burkholderia: proposal for division of this genus into the emended genus Burkholderia containing pathogenic organisms and a new genus Paraburkholderia gen. nov harboring environmental species. Front. Genet. 5:429 10.3389/fgene.2014.00429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spilker T., Baldwin A., Bumford A., Dowson C. G., Mahenthiralingam E., Lipuma J. J. (2009). Expanded multilocus sequence typing for Burkholderia species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47 2607–2610. 10.1128/JCM.00770-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Moreno Z. R., Caballero-Mellado J., Coutinho B. G., Mendonca-Previato L., James E. K., Venturi V. (2012). Common features of environmental and potentially beneficial plant-associated Burkholderia. Microb. Ecol. 63 249–266. 10.1007/s00248-011-9929-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sueoka M. (1961). Compositional correlation between deoxyribonucleic acid and protein. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 26 35–43. 10.1101/SQB.1961.026.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunagawa S., Mende D. R., Zeller G., Izquierdo-Carrasco F., Berger S. A., Kultima J. R., et al. (2013). Metagenomic species profiling using universal phylogenetic marker genes. Nat. Methods 10 1196–1199. 10.1038/nmeth.2693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suyama M., Torrents D., Bork P. (2006). PAL2NAL: robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 34 W609–W612. 10.1093/nar/gkl315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2014). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Thiergart T., Landan G., Martin W. F. (2014). Concatenated alignments and the case of the disappearing tree. BMC Evol. Biol. 14:266 10.1186/s12862-014-0266-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tindall B. J., Rossello-Mora R., Busse H. J., Ludwig W., Kampfer P. (2010). Notes on the characterization of prokaryote strains for taxonomic purposes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 60 249–266. 10.1099/ijs.0.016949-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torbeck L., Raccasi D., Guilfoyle D. E., Friedman R. L., Hussong D. (2011). Burkholderia cepacia: this decision is overdue. PDA J. Pharm. Sci. Technol. 65 535–543. 10.5731/pdajpst.2011.00793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandamme P., Opelt K., Knochel N., Berg C., Schonmann S., De Brandt E., et al. (2007). Burkholderia bryophila sp. nov. and Burkholderia megapolitana sp. nov., moss-associated species with antifungal and plant-growth-promoting properties. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57 2228–2235. 10.1099/ijs.0.65142-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandamme P., Peeters C. (2014). Time to revisit polyphasic taxonomy. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 106 57–65. 10.1007/s10482-014-0148-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandamme P., Vancanneyt M., Pot B., Mels L., Hoste B., Dewettinck D., et al. (1992). Polyphasic taxonomic study of the emended genus Arcobacter with Arcobacter butzleri comb. nov. and Arcobacter skirrowii sp. nov., an aerotolerant bacterium isolated from veterinary specimens. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 42 344–356. 10.1099/00207713-42-3-344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Mering C., Jensen L. J., Snel B., Hooper S. D., Krupp M., Foglierini M., et al. (2005). STRING: known and predicted protein-protein associations, integrated and transferred across organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 D433–D437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wand M. E., Muller C. M., Titball R. W., Michell S. L. (2011). Macrophage and Galleria mellonella infection models reflect the virulence of naturally occurring isolates of B. pseudomallei, B. thailandensis and B. oklahomensis. BMC Microbiol. 11:11 10.1186/1471-2180-11-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Wu M. (2013). A phylum-level bacterial phylogenetic marker database. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30 1258–1262. 10.1093/molbev/mst059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willcocks S. J., Denman C. C., Atkins H. S., Wren B. W. (2016). Intracellular replication of the well-armed pathogen Burkholderia pseudomallei. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 29 94–103. 10.1016/j.mib.2015.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y.-C., Abd El Ghany M., Naeem R., Lee K.-W., Tan Y.-C., Pain A., et al. (2016). Candidate essential genes in Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315 identified by genome-wide TraDIS. Front. Microbiol. 7:1288 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuuchi E., Kosako Y., Oyaizu H., Yano I., Hotta H., Hashimoto Y., et al. (1992). Proposal of Burkholderia gen. nov. and transfer of seven species of the genus Pseudomonas homology group II to the new genus, with the type species Burkholderia cepacia (Palleroni and Holmes 1981) comb. nov. Microbiol. Immunol. 36 1251–1275. 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1992.tb02129.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. H. (2007). PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24 1586–1591. 10.1093/molbev/msm088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. H., Nielsen R. (2000). Estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates under realistic evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17 32–43. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S. H., Ha S. M., Kwon S., Lim J., Kim Y., Seo H., et al. (2017). Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA and whole genome assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 67 1613–1617. 10.1099/ijsem.1090.001755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yutin N., Puigbo P., Koonin E. V., Wolf Y. I. (2012). Phylogenomics of prokaryotic ribosomal proteins. PLoS ONE 7:e36972 10.1371/journal.pone.0036972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

TABLE S1 | ANI values between strain LMG 28154T and phylogenetically neighboring species.

TABLE S2 | Functions from the core genome of strains B. thailandensis E264T, B. pseudomallei K96243 and B. oklahomensis C6786T lacking from the genome of LMG 28154T.