Abstract

Earth harbors a highly diverse array of plant leaf forms. A well-known pattern linking diverse leaf forms with their photosynthetic function across species is the global leaf economics spectrum (LES). However, within homogeneous plant functional groups such as tropical woody angiosperms or temperate deciduous woody angiosperms, many species can share a similar position in the LES but differ in other vital leaf traits, and thus function differently under the given suite of environmental drivers. How diverse leaves differentiate from each other has yet to be fully explained. Here, we propose a new perspective for linking leaf structure and function by arguing that a leaf may be divided into three key sub-modules, the light capture module, the water-nutrient flow module and the gas exchange module. Each module consists of a set of leaf tissues corresponding to a certain resource acquisition function, and the combination and configuration of different modules may differ depending on overall leaf functioning in a given environment. This modularized-leaf perspective differs from the whole-leaf perspective used in leaf economics theory and may serve as a valuable tool for tracing the evolution of leaf form and function. This perspective also implies that the evolutionary direction of various leaf designs is not to optimize a single critical trait, but to optimize the combination of different traits to better adapt to the historical and current environments. Future studies examining how different modules are synchronized for overall leaf functioning should offer critical insights into the diversity of leaf designs worldwide.

Keywords: leaf anatomical structure, leaf diversity, leaf form, leaf function, stomata, venation

Introduction

As the metabolic engine of plant growth, leaves are marvelous examples of biological complexity and natural beauty (Vogel, 2012; Sack, 2013). Remarkable diversity occurs in the designs of leaf form and function. On what principles do diverse leaf forms and functions vary from one species to another? Comparative studies of leaf functional traits have been highly successful at identifying key trade-offs in leaf form and function (Givnish, 1987; Westoby et al., 2002; Ackerly, 2004). Among the numerous successes, the most noteworthy is probably the global leaf economics spectrum (LES), which states that a universal trade-off exists between leaf construction costs [characterized by leaf dry mass per area (LMA)] and leaf lifespan (LL) across different biomes and contrasting plant functional groups (Wright et al., 2004). This whole-leaf level cost-benefit perspective has been valuable for understanding leaf carbon balance as well as whole plant growth (Poorter et al., 2013; Westoby et al., 2013; Reich, 2014).

Although highly successful, the economics spectrum may be insufficient for a full understanding of the complex evolutionary steps and adaptation to current abiotic and biotic environments in leaves as well as in whole plants. Emerging studies have revealed that leaves with similar LMA can differ in other critical traits such as leaf hydraulics (Sack et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015; Blackman et al., 2016), stomatal conductance (Reich et al., 1999) and leaf drought tolerance (Maréchaux et al., 2015) as well as whole plant drought and shade tolerances (Hallik et al., 2009). These studies suggest that different species do not always spread out widely along a single axis of carbon economy (i.e., LMA-LL); rather, they may vary along multiple dimensions of trait trade-offs. In fact, only through the lens of multiple dimensions of leaf traits and corresponding ecological and physiological functions, the immense diversity of leaf designs observed in the plant kingdom does seem possible (Laughlin, 2014; Li et al., 2015; Blackman et al., 2016).

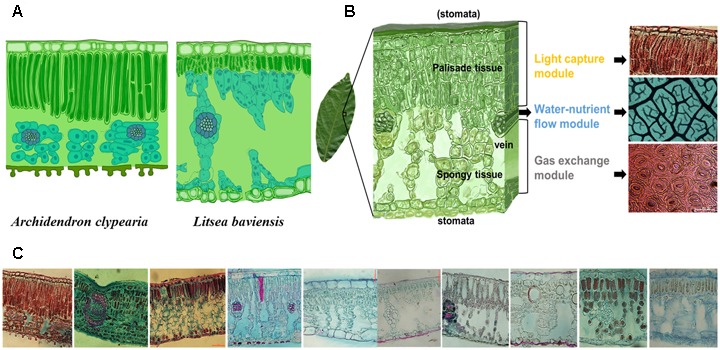

To fully understand the multi-dimensionality of leaf form and function, a whole leaf needs to be divided into different component parts, each responsible for a specific function. Indeed, LMA is a product of leaf thickness and tissue density (Niinemets, 1999; Poorter et al., 2009), both of which are influenced by anatomical drivers such as leaf cellular and tissue composition, airspace volume and structure, and ultrastructural cell characteristics (Villar et al., 2013; John et al., 2017). Different combinations of leaf anatomical traits can result in similar LMA values across species (Figure 1A), but different values of these traits affect leaf-level water transport (Tyree et al., 1999; Sack et al., 2003; Sack and Holbrook, 2006; Brodribb, 2015; Buckley et al., 2015), CO2 diffusion (Terashima et al., 2011; Muir et al., 2016), and light capture (Vogelmann et al., 1996) differently. Therefore, a whole leaf analysis alone might hide the linkages between the key structural components and their corresponding functions. For a fully functional analysis, it can be illuminating to employ the concept of modularity, which implies that different independent (or semi-independent) modules each carrying a different function can be integrated as a whole (Wagner and Altenberg, 1996).

FIGURE 1.

Illustration of the concept of modularity of leaf design. Different species can have different internal leaf structures such that the key leaf trait, leaf dry mass per unit area (LMA) alone may not be informative enough for describing the diversity of leaf designs as exemplified by a comparison of two species with similar LMA (77.3 g m-2 for Archidendron clypearia and 68.9 g m-2 for Litsea baviensis) (A). A frequently observed mode for the combination of three key sub-leaf modules: from top to bottom, a leaf can be divided into a light capture module, a water-nutrient flow module and a gas exchange module (B). Demonstration of the vast diversity of leaf internal structures. Such diverse leaf designs can be seen as the result of different adjustments to the frequently-observed mode (C).

Here, we propose that a leaf can be divided into three key modules, and each module is composed of a set of correlated leaf traits. We emphasize that different modules are not necessarily fully independent from each other, but identifying each module can serve as a tool for tracing the evolutionary pathways of key leaf physiognomies and functions. We also argue that a leaf is an evolutionary patchwork composed of separate modules and that deciphering different trait combinations of the modules will offer new insights into the diverse leaf structures and functioning.

Three Key Sub-Leaf Modules

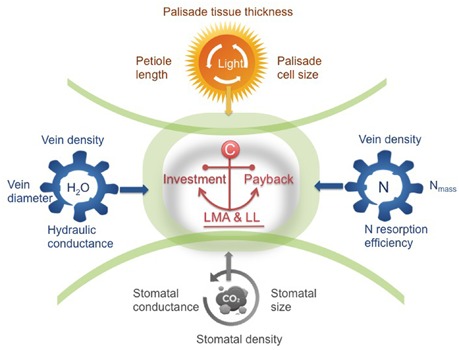

A leaf is highly heterogeneous in its structure and can be divided into three major types of modules corresponding to light capture, water-nutrient transport, and CO2 absorption. The first module is the light capture module, which is mainly composed of epidermal cells and tightly packed palisade cells (Figure 1B). The epidermal cells are transparent and do not contain chlorophyll, however, the outer cell wall can function as a lens focusing light deeper into the leaf interior (Vogelmann and Björn, 1986; Martin et al., 1989; Poulson and Vogelmann, 1990). Furthermore, palisade cells can operate as optical fibers, allowing the penetration of light deeper into the leaf (Vogelmann and Martin, 1993; Smith et al., 1997; Brodersen et al., 2008). Nevertheless, due to high concentration of chlorophyll, palisade cells are responsible for the majority of light capture (Lee et al., 1990; Vogelmann et al., 1996). Besides, leaf petioles and midribs serve to determine leaf angle (Niinemets et al., 2006, 2007b), which further can modulate light interception (Salisbury, 1949; Smith et al., 1998; Falster and Westoby, 2003; de Boer et al., 2016). Apart from these main components, some plant species can have unique features such as vertical sclereids that can also function as optical fibers for light penetration (Karabourniotis, 1998; Nikolopoulos et al., 2002). Typically, the light capture module is primarily associated with the upper layer of a leaf, especially for horizontally inclined leaves (Parkhurst and Givnish, 1986; Smith et al., 1997). In particular, in dense canopies (e.g., forests and woodlands as well as dicot herb canopies), most leaves receive light from high solar inclination angles; once the light enters the leaf, light intensity decreases rapidly (Vogelmann et al., 1996). Some key trait characteristics to this module include epidermal outer cell wall properties, palisade cell size, palisade tissue thickness, chlorophyll content, and petiole length (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

A trait framework based on the three key sub-leaf modules. In the center, the leaf economics spectrum (LES) concept of integrating investment and payback (LMA and leaf longevity, LL) is a fundamental principle, defining the trade-offs of the three modules. By unpacking the trade-off between LMA-LL into four other relations (i.e., interactions between leaves and light-water-nutrients-gas composition), we show the pathway moving beyond traditional leaf economics. Taking this framework as a starting point, we can have a more holistic understanding of global-scale variation in leaf structure and function. Certain trait syndromes are suggested for each module, ranging from cell size, tissue-level density or thickness to the rates of physiological processes.

The second module is the water-nutrient flow module, which is mainly composed of leaf venation network (Figure 1B). The leaf venation network consists of both major and minor veins, with major veins being responsible for transport and partitioning of water and nutrients hierarchically throughout different orders of leaf venation system, and minor veins being responsible for delivering the water to precise locations to meet the water demands for photosynthesis and water transpiration through the stomata (Roth-Nebelsick et al., 2001; Sack and Holbrook, 2006; Brodribb et al., 2007; Sack and Scoffoni, 2013). Furthermore, leaf venation provides an indispensable network for the flow of nutrients and other materials throughout the leaf and to outside the leaf via phloem and xylem, including nitrogen resorption (Zhang et al., 2015) and export of photosynthetic products (Turgeon, 2006). Some key traits involved in water-nutrient flow module include vein diameter and density, vessel (or tracheid) size and density, leaf hydraulic conductance and nitrogen resorption efficiency (Figure 2).

The third module is the gas exchange module, which is mainly composed of stomata and connected intercellular air spaces in the palisade and spongy mesophyll and mesophyll cells with chloroplasts (Figure 1B). Stomata are sensitive valves for CO2- H2O exchange and can respond rapidly to plant water availability and evaporative demand, which is influenced by air humidity and leaf temperature as affected by ambient temperature and leaf radiation interception and loss (Smith et al., 1997; Hetherington and Woodward, 2003; Franks et al., 2009). In addition, chloroplast characteristics and cell position alter the gradients of CO2 diffusion from sub-stomatal cavities to chloroplasts (Flexas et al., 2012; Tomás et al., 2013; Tosens et al., 2016). Variation of stomatal structure, such as stomatal crypts and waxy deposits can also affect leaf gas exchange (Roth-Nebelsick, 2007). Some key traits involved in the gas exchange module include stomatal size, stomatal density, stomatal conductance, the size and distribution of chloroplasts with respect to cell walls and exposure of cell walls to the gas phase inside the leaf, and photosynthetic capacity per cell (Figure 2).

Evolutionary History for Each Sub-Leaf Module

In understanding the current diversity across these three sub-modules, it is important to consider that the evolution of different leaf modules was often largely independent, i.e., key features of each module evolved in response to their most prominent selection pressures. The light capture module underwent substantial selection as plants radiated to more open habitats (Feild and Arens, 2005), the water-nutrient flow module was modified by ever increasing transpirational pull in more open habitats (Feild et al., 2003), and the gas exchange module was modified in response to the gradually declining atmospheric CO2 concentration (Franks and Beerling, 2009). Over time, different configurations of these modules were combined into various leaves. The evolutionary direction of various leaf designs is not to optimize a single critical trait or module, but to optimize the combination of different traits to better adapt to the highly variable historical and extant environments that diverse species across different plant types occupy.

In particular, for angiosperms which constitute one of the most important plant groups in terms of species diversity and biomass production on the Earth, the 400-million-year history is also a step-by-step process. Fewer trait combinations among a limited number of early angiosperm species diversified into more trait combinations among a high number of derived angiosperm species. During this process, gaining new advanced functions and capacities was a key mechanism for angiosperm radiation and diversification. Compared to other plant groups, the underlying superiority of angiosperms in having more diverse trait combinations is also confirmed by recent global synthesis of leaf traits (see Diaz et al., 2016).

During early angiosperm evolution, the light capture module was rather weakly developed among woody angiosperms (i.e., during the early Cretaceous c. 135 Ma) (Bond and Scott, 2010). Many ancestral species, such as Amborella, had little or no differentiation of palisade mesophyll from spongy mesophyll (Feild et al., 2003; Feild and Arens, 2005). Such a weakly developed light capture module was widespread in the understory shady habitats (Feild and Arens, 2005; Bond and Scott, 2010). Yet, as more woody angiosperms radiated into open habitats, a more clearly differentiated light capture module began to appear, especially among canopy angiosperms. These species shared the common characteristic of multiple layers of tightly packed palisade tissue.

The evolution of water-nutrient flow module has also been a step by step process. One notable aspect of this gradual process is the substantial increase of vein density in angiosperms compared to other plant groups (Boyce et al., 2009; Feild et al., 2011a), which took about 250 million years. High leaf vein densities endowed woody angiosperms with higher leaf water supply capacity than that in their competitors (Boyce et al., 2009), and contributed to the rise of photosynthetic capacity in the early angiosperm diversification (Brodribb and Feild, 2010), but nevertheless, there are still large differences in leaf vein density within this group (Boyce et al., 2009). Other concurrent innovations include the decreasing size of vein diameter (Feild and Brodribb, 2013), the unique spatial arrangements of veins (Zwieniecki and Boyce, 2014), the modifications of perforation plates of primary xylem vessels (Feild and Brodribb, 2013), and the reduction of cell wall thickness and chloroplast size improving the rate of CO2 diffusion into chloroplasts (Tosens et al., 2016; Veromann et al., 2017), all these traits showing higher overall values than more ancient plant groups but large differences within the woody angiosperm groups.

Concurrently with the decline in atmospheric CO2 concentration, innovations of the gas exchange module took place gradually over the past 400 million years. As atmospheric CO2 concentration decreased, stomatal density increased, while stomatal size decreased among most land plants. The increases in stomatal density contributed to an overall increase in the maximum stomatal conductance, while decreased stomatal size enabled greater sensitivity to environmental changes (Franks and Beerling, 2009). In the early Cretaceous, early angiosperm leaves had a low gas exchange capacity with a low maximum stomatal pore area (Feild et al., 2011b). The overall superior performance of angiosperms was achieved by gaining the capacity to close stomata in response to high CO2 concentration, ensuring a higher water use efficiency than that in other lower land plants (Brodribb et al., 2009), but again, with high variations across species within this group.

Diversity of Leaf Designs

An important goal of this paper is to highlight how a modularized-leaf perspective may provide a useful approach for characterizing and understanding the variation of leaf form and function beyond traditional LES perspective (Figure 1C). LES mainly defines the large-scale leaf design patterns across different leaf types and different biomes, while our concepts of key sub-leaf modules can further describe the variation of smaller-scale leaf designs within one leaf type or/and one plant functional type (PFT) or/and one biome. Though LES has a great value in revealing global-scale leaf strategies (Diaz et al., 2016), it is insufficient for describing the diversity of leaf designs. A global meta-analysis of variation of LMA demonstrated that LMA failed to distinguish between species within a biome or a functional group (Poorter et al., 2009). For example, within species-rich subtropical forests, Pithecellobium clypearia and Litsea baviensis (77.3 and 68.9 g m-2) are both evergreen woody angiosperms species with similar LMA, but they can differ markedly in leaf light-capture and water-nutrient flow modules (Figure 1A). As already argued, different species can differentiate their leaves by modifying module-level traits without altering the values of LMA (Figure 2). Ultimately, the divergent modular construction of leaves underlies the emergent trade-offs between leaf structures and function known as the worldwide LES (Wright et al., 2004).

In fact, different sub-leaf modules are not necessarily fully independent from each other, and plenty of studies have shown coordinated variation across modules (e.g., Sack et al., 2003; Brodribb et al., 2005, 2007). Given that different modules develop together, they might often be interdependent. Especially, when there is a limiting factor (e.g., light, nutrients, or water), these three sub-leaf modules would converge toward maximizing the use of the limiting resource (Mason and Donovan, 2015). Nonetheless, even though different modules co-vary, the direction of such covariations is not fixed. For instance, leaf nitrogen concentration can be either positively (Schulze et al., 1994), or negatively correlated (Taylor and Eamus, 2008) with maximum stomatal conductance.

Even more importantly, under non-constraining growth conditions, key traits corresponding to each module can have room to evolve independently and maximize each function separately without constrains limiting these maxima. For example, leaf carbon and water use related traits are independent among 85 woody angiosperms in tropical-subtropical forests (Li et al., 2015), and vein density (water-nutrient flow module) was unrelated to stomatal conductance (gas-exchange module) among 35 evergreen Australian angiosperms (Gleason et al., 2016). Such independence across modules can lead to diverse combinations of different traits, and consequently to the high diversity of leaf designs in species-rich biomes. Indeed, leaves do contain different fractions of mesophyll, epidermis and vascular tissues, and these fractions always adjust to different environmental conditions, with different environmental pressures altering the distribution of leaf tissues in different manners (Niinemets, 1999; Niinemets et al., 2007a). In fact, if sub-leaf modules always co-varied and did so in a consistent manner, possible combinations of leaf structures across species would be very few, leaving relatively little room for adaptation to different environments.

Although we often find these three modules arranged in the sequence shown in Figure 1B, spatial arrangements of these sub-leaf modules can vary across different habitats and different plant types (e.g., angiosperms, gymnosperms, ferns, mosses, and aquatic plants). Variation in modular arrangement can lead to different configurations of these three key modules, and consequently to even greater diversity of leaf designs. Stomata can develop on both surfaces of a leaf, termed as amphistomatous leaves (Parkhurst, 1978), which is a derived feature for angiosperms (Mott et al., 1982). Amphistomatous species with high conductance to CO2 diffusion (Mott et al., 1982; Beerling and Kelly, 1996; Muir, 2015) are most common among fast-growing species (Muir, 2015), and are usually successful in high-light habitats (Mott et al., 1982; Beerling and Kelly, 1996; Muir, 2015). Similarly, palisade cells can also be found on both the lower and upper layers of a leaf (Smith et al., 1997). Examples can be found in the isobilateral leaves of eucalypts in arid environments (Evans et al., 1993; Ögren and Evans, 1993; de Boer et al., 2016), and in the trees of the open savannas in the Amazon (e.g., Byrsonima crassifolia) (Ferreira et al., 2015).

Future Directions

From the perspective of leaf modularity, studies of leaf functional traits and leaf diversity are approaching a new era. Recognizing the corresponding trait syndromes for each module, rather than focusing only on whole-leaf traits, is strongly recommended for future leaf trait-based studies attempting to understand the mechanisms of species diversity and species-environment relationships (Figure 2). The LES concept of integrating investment and payback (LMA-LL) is a fundamental principle, defining the trade-offs of the three modules. Thus, variation in LMA is a by-product of individual responses of different modules to the environment (Figure 2). By considering different components of LMA in relation to four key environmental drivers (i.e., light, water, and nutrient availabilities, and gas composition) (Figure 2), and examining how different modules interact with the environment, we can obtain a more mechanistic understanding of patterns of leaf structure and function at both local and global scales. Besides, to improve predictions of species responses to environmental changes, more attention should be paid to the environmental response curves of each module in future predictive models of global change that intend to use leaf traits to predict future vegetation.

Another important step forward will be to examine trait combinations of different sub-leaf modules across species at the global scale. In this way, we can pinpoint the underlying mechanisms driving different ecological strategies and high leaf diversity. Under such a framework, both significant and non-significant correlations among different leaf traits can be useful for identifying coordination and independence both within and among different modules. Furthermore, we can trace back how different modules were integrated into a single leaf over time among different plant functional groups having different leaf types. In future biodiversity models, detailed leaf functional types (LFTs) can be defined for better representation of leaf diversity, by identifying different combinations of sub-leaf modules both within one PFT and across different PFTs. Overall, combinations of different modules have contributed to different leaf ecological strategies and thus, to tremendous plant diversity over the long evolutionary history, and will continue to shape leaf and whole-plant responses in the future.

Author Contributions

LL and DG developed the idea. LL prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors made substantial contributions to the revision of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Luke McCormack for insightful comments on the earlier version of the manuscript. We thank Haowen Si and Wei Zhou for the anatomical pictures in Figure 1C. We also apologize to all authors whose relevant work was not cited due to space constraints.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC grant no. 31530011, no. 31325006).

References

- Ackerly D. (2004). Functional strategies of chaparral shrubs in relation to seasonal water deficit and disturbance. Ecol. Monogr. 74 25–44. 10.1890/03-4022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beerling D. J., Kelly C. K. (1996). Evolutionary comparative analyses of the relationship between leaf structure and function. New Phytol. 134 35–51. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1996.tb01144.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman C. J., Aspinwall M. J., Resco de Dios V., Smith R. A., Tissue D. T. (2016). Leaf photosynthetic, economics and hydraulic traits are decoupled among genotypes of a widespread species of eucalypt grown under ambient and elevated CO2. Funct. Ecol. 30 1491–1500. 10.1111/1365-2435.12661 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bond W. J., Scott A. C. (2010). Fire and the spread of flowering plants in the Cretaceous. New Phytol. 188 1137–1150. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03418.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce C. K., Brodribb T. J., Feild T. S., Zwieniecki M. A. (2009). Angiosperm leaf vein evolution was physiologically and environmentally transformative. Proc. Biol. Sci. 276 1771–1776. 10.1098/rspb.2008.1919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodersen C. R., Vogelmann T. C., Williams W. E., Gorton H. L. (2008). A new paradigm in leaf-level photosynthesis: direct and diffuse lights are not equal. Plant Cell Environ. 31 159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb T. J. (2015). Bringing anatomy back into the equation. Plant Physiol. 168 1461 10.1104/pp.15.01021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb T. J., Feild T. S. (2010). Leaf hydraulic evolution led a surge in leaf photosynthetic capacity during early angiosperm diversification. Ecol. Lett. 13 175–183. 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01410.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb T. J., Feild T. S., Jordan G. J. (2007). Leaf maximum photosynthetic rate and venation are linked by hydraulics. Plant Physiol. 144 1890–1898. 10.1104/pp.107.101352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb T. J., Holbrook N. M., Zwieniecki M. A., Palma B. (2005). Leaf hydraulic capacity in ferns, conifers and angiosperms: impacts on photosynthetic maxima. New Phytol. 165 839–846. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01259.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodribb T. J., McAdam S. A., Jordan G. J., Feild T. S. (2009). Evolution of stomatal responsiveness to CO2 and optimization of water-use efficiency among land plants. New Phytol. 183 839–847. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02844.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley T., Grace P. J., Scoffoni C., Sack L. (2015). How does leaf anatomy influence water transport outside the xylem? Plant Physiol. 168 1616–1635. 10.1104/pp.15.00731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer H. J., Drake P. L., Wendt E., Price C., Schulze E.-D., Turner N. C., et al. (2016). Over-investment in leaf venation relaxes morphological constraints on photosynthesis in eucalypts. Plant Physiol. 172 2286–2299. 10.1104/pp.16.01313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz S., Kattge J., Cornelissen J. H., Wright I. J., Lavorel S., Dray S., et al. (2016). The global spectrum of plant form and function. Nature 529 167–171. 10.1038/nature16489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J. R., Jakobsen I., Ögren E. (1993). Photosynthetic light-response curves. 2. Gradients of light absorption and photosynthetic capacity. Planta 189 191–200. 10.1007/BF00195076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Falster D. S., Westoby M. (2003). Leaf size and angle vary widely across species: what consequences for light interception? New Phytol. 158 509–525. 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2003.00765.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feild T. S., Arens N. C. (2005). Form, function and environments of the early angiosperms: merging extant phylogeny and ecophysiology with fossils. New Phytol. 166 383–408. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01333.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feild T. S., Arens N. C., Dawson T. E. (2003). The ancestral ecology of angiosperms: emerging perspectives from extant basal lineages. Int. J. Plant Sci. 164 S129–S142. 10.1086/374193 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feild T. S., Brodribb T. J. (2013). Hydraulic tuning of vein cell microstructure in the evolution of angiosperm venation networks. New Phytol. 199 720–726. 10.1111/nph.12311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feild T. S., Brodribb T. J., Iglesias A., Chatelet D. S., Baresch A., Upchurch G. R., et al. (2011a). Fossil evidence for Cretaceous escalation in angiosperm leaf vein evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 8363–8366. 10.1073/pnas.1014456108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feild T. S., Upchurch G. R., Chatelet D. S., Brodribb T. J., Grubbs K. C., Samain M.-S., et al. (2011b). Fossil evidence for low gas exchange capacities for Early Cretaceous angiosperm leaves. Paleobiology 37 195–213. 10.1073/pnas.1014456108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira C. S., Carmo W. S. D., Graciano-Ribeiro D., Oliveira J. M. F. D., Melo R. B. D., Franco A. C. (2015). Anatomia da lâmina foliar de onze espécies lenhosas dominantes nas savanas de Roraima. Acta Amazon. 45 337–346. 10.1590/1809-4392201500363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flexas J., Barbour M. M., Brendel O., Cabrera H. M., Carriquí M., Diaz-Espejo A., et al. (2012). Mesophyll diffusion conductance to CO2: an unappreciated central player in photosynthesis. Plant Sci. 193–194 70–84. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks P. J., Beerling D. J. (2009). Maximum leaf conductance driven by CO2 effects on stomatal size and density over geologic time. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 10343–10347. 10.1073/pnas.0904209106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks P. J., Drake P. L., Beerling D. J. (2009). Plasticity in maximum stomatal conductance constrained by negative correlation between stomatal size and density: an analysis using Eucalyptus globulus. Plant Cell Environ. 32 1737–1748. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.002031.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Givnish T. J. (1987). Comparative studies of leaf form: assessing the relative roles of selective pressures and phylogenetic constraints. New Phytol. 106 131–160. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1987.tb04687.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason S. M., Westoby M., Jansen S., Choat B., Hacke U. G., Pratt R. B., et al. (2016). Weak tradeoff between xylem safety and xylem-specific hydraulic efficiency across the world’s woody plant species. New Phytol. 209 123–136. 10.1111/nph.13646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallik L., Niinemets, Ü., Wright I. J. (2009). Are species shade and drought tolerance reflected in leaf-level structural and functional differentiation in Northern Hemisphere temperate woody flora? New Phytol. 184 257–274. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02918.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington A. M., Woodward F. I. (2003). The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature 424 901–908. 10.1038/nature01843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John G. P., Scoffoni C., Buckley T. N., Villar R., Poorter H., Sack L. (2017). The anatomical and compositional basis of leaf mass per area. Ecol. Lett. 20 412–425. 10.1111/ele.12739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karabourniotis G. (1998). Light-guiding function of foliar sclereids in the evergreen sclerophyll Phillyrea latifolia: a quantitative approach. J. Exp. Bot. 49 739–746. 10.1093/jxb/49.321.739 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin D. C. (2014). The intrinsic dimensionality of plant traits and its relevance to community assembly. J. Ecol. 102 186–193. 10.1111/1365-2745.12187 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D. W., Bone R. A., Tarsis S. L., Storch D. (1990). Correlates of leaf optical properties in tropical forest sun and extreme-shade plants. Am. J. Bot. 77 370–380. 10.2307/2444723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., McCormack M. L., Ma C., Kong D., Zhang Q., Chen X., et al. (2015). Leaf economics and hydraulic traits are decoupled in five species-rich tropical-subtropical forests. Ecol. Lett. 18 899–906. 10.1111/ele.12466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maréchaux I., Bartlett M. K., Sack L., Baraloto C., Engel J., Joetzjer E., et al. (2015). Drought tolerance as predicted by leaf water potential at turgor loss point varies strongly across species within an Amazonian forest. Funct. Ecol. 29 1268–1277. 10.1111/1365-2435.12452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G., Josserand S. A., Bornman J. F., Vogelmann T. C. (1989). Epidermal focussing and the light microenvironment within leaves of Medicago sativa. Physiol. Plant. 76 485–492. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1989.tb05467.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason C. M., Donovan L. A. (2015). Evolution of the leaf economics spectrum in herbs: evidence from environmental divergences in leaf physiology across Helianthus (Asteraceae). Evolution 69 2705–2720. 10.1111/evo.12768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott K. A., Gibson A. C., O’leary J. W. (1982). The adaptive significance of amphistomatic leaves. Plant Cell Environ. 5 455–460. 10.1111/1365-3040.ep11611750 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muir C. D. (2015). Making pore choices: repeated regime shifts in stomatal ratio. Proc. Biol. Sci. 282:20151498 10.1098/rspb.2015.1498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir C. D., Conesa M. À., Roldán E. J., Molins A., Galmés J. (2016). Weak coordination between leaf structure and function among closely related tomato species. New Phytol. 213 1642–1653. 10.1111/nph.14285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets, Ü. (1999). Components of leaf dry mass per area–thickness and density–alter leaf photosynthetic capacity in reverse directions in woody plants. New Phytol. 144 35–47. 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1999.00466.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets U., Lukjanova A., Turnbull M. H., Sparrow A. D. (2007a). Plasticity in mesophyll volume fraction modulates light-acclimation in needle photosynthesis in two pines. Tree Physiol. 27 1137–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü., Portsmuth A., Tobias M. (2006). Leaf size modifies support biomass distribution among stems, petioles and mid-ribs in temperate plants. New Phytol. 171 91–104. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01741.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niinemets Ü., Portsmuth A., Tobias M. (2007b). Leaf shape and venation pattern alter the support investments within leaf lamina in temperate species: a neglected source of leaf physiological differentiation? Funct. Ecol. 21 28–40. 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2006.01221.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolopoulos D., Liakopoulos G., Drossopoulos I., Karabourniotis G. (2002). The relationship between anatomy and photosynthetic performance of heterobaric leaves. Plant Physiol. 129 235–243. 10.1104/pp.010943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ögren E., Evans J. R. (1993). Photosynthetic light-response curves. 1. The influence of CO2 partial pressure and leaf inversion. Planta 189 182–190. 10.1007/BF00195075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst D., Givnish T. (1986). “Internal leaf structure: a three-dimensional perspective”, in On the Economy of Plant Form and Function ed. Givnish T. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ) 215–249. [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst D. F. (1978). The adaptive significance of stomatal occurrence on one or both surfaces of leaves. J. Ecol. 66 367–383. 10.2307/2259142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H., Lambers H., Evans J. R. (2013). Trait correlation networks: a whole-plant perspective on the recently criticized leaf economic spectrum. New Phytol. 201 378–382. 10.1111/nph.12547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poorter H., Niinemets Ü., Poorter L., Wright I. J., Villar R. (2009). Tansley review. Causes and consequences of variation in leaf mass per area (LMA): a meta-analysis. New Phytol. 182 565–588. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02830.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulson M. E., Vogelmann T. C. (1990). Epidermal focussing and effects upon photosynthetic light-harvesting in leaves of Oxalis. Plant Cell Environ. 13 803–811. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1990.tb01096.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reich P. B. (2014). The world-wide ‘fast–slow’ plant economics spectrum: a traits manifesto. J. Ecol. 102 275–301. 10.1111/1365-2745.12211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reich P. B., Ellsworth D. S., Walters M. B., Vose J. M., Gresham C., Volin J. C., et al. (1999). Generality of leaf trait relationships: a test across six biomes. Ecology 80 1955–1969. 10.1890/0012-9658(1999)080[1955:GOLTRA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roth-Nebelsick A. (2007). Computer-based studies of diffusion through stomata of different architecture. Ann. Bot. 100 23–32. 10.1093/aob/mcm075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth-Nebelsick A., Uhl D., Mosbrugger V., Kerp H. (2001). Evolution and function of leaf venation architecture: a review. Ann. Bot. 87 553–566. 10.1006/anbo.2001.1391 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sack L. (2013). Holding a leaf up to the light. BioScience 63 981–982. 10.1525/bio.2013.63.12.12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sack L., Cowan P., Jaikumar N., Holbrook N. (2003). The ‘hydrology’ of leaves: co-ordination of structure and function in temperate woody species. Plant Cell Environ. 26 1343–1356. 10.1046/j.0016-8025.2003.01058.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sack L., Holbrook N. M. (2006). Leaf hydraulics. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 57 361–381. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.56.032604.144141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack L., Scoffoni C. (2013). Leaf venation: structure, function, development, evolution, ecology and applications in the past, present and future. New Phytol. 198 983–1000. 10.1111/nph.12253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sack L., Scoffoni C., John G. P., Poorter H., Mason C. M., Mendez-Alonzo R., et al. (2014). Leaf mass per area is independent of vein length per area: avoiding pitfalls when modelling phenotypic integration (reply to Blonder et al. 2014) J. Exp. Bot. 65 5115–5123. 10.1093/jxb/eru305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury E. (1949). Leaf form and function. Nature 163 515–518. 10.1038/163515a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze E., Kelliher F. M., Korner C., Lloyd J., Leuning R. (1994). Relationships among maximum stomatal conductance, ecosystem surface conductance, carbon assimilation rate, and plant nitrogen nutrition: a global ecology scaling exercise. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 25 629–662. 10.1146/annurev.es.25.110194.003213 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith W., Bell D., Shepherd K. (1998). Associations between leaf structure, orientation, and sunlight exposure in five Western Australian communities. Am. J. Bot. 85 56 10.2307/2446554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith W. K., Vogelmann T. C., DeLucia E. H., Bell D. T., Shepherd K. A. (1997). Leaf form and photosynthesis. Bioscience 47 785–793. 10.2307/1313100 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D. T., Eamus D. (2008). Coordinating leaf functional traits with branch hydraulic conductivity: resource substitution and implications for carbon gain. Tree Physiol. 28 1169–1177. 10.1093/treephys/28.8.1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I., Hanba Y. T., Tholen D., Niinemets U. (2011). Leaf functional anatomy in relation to photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 155 108–116. 10.1104/pp.110.165472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomás M., Flexas J., Copolovici L., Galmés J., Hallik L., Medrano H., et al. (2013). Importance of leaf anatomy in determining mesophyll diffusion conductance to CO2 across species: quantitative limitations and scaling up by models. J. Exp. Bot. 64 2269–2281. 10.1093/jxb/ert086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosens T., Nishida K., Gago J., Coopman R., Cabrera H. M., Carriquí M., et al. (2016). The photosynthetic capacity in 35 ferns and fern allies: mesophyll CO2 diffusion as a key trait. New Phytol. 209 1576–1590. 10.1111/nph.13719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turgeon R. (2006). Phloem loading: how leaves gain their independence. Bioscience 56 15–24. 10.1641/0006-3568(2006)056[0015:PLHLGT]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tyree M., Sobrado M., Stratton L., Becker P. (1999). Diversity of hydraulic conductance in leaves of temperate and tropical species: possible causes and consequences. J. Trop. For. Sci. 11 47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Veromann L. L., Tosens T., Laanisto L., Niinemets Ü. (2017). Extremely thick cell walls and low mesophyll conductance: welcome to the world of ancient living! J. Exp. Bot. 68 1639–1653. 10.1093/jxb/erx045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar R., Ruiz-Robleto J., Ubera J. L., Poorter H. (2013). Exploring variation in leaf mass per area (LMA) from leaf to cell: an anatomical analysis of 26 woody species. Am. J. Bot. 100 1969–1980. 10.3732/ajb.1200562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel S. (2012). The Life of a Leaf. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. 10.7208/chicago/9780226859422.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelmann T., Björn L. O. (1986). Plants as light traps. Physiol. Plant. 68 704–708. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1986.tb03421.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelmann T., Martin G. (1993). The functional significance of palisade tissue: penetration of directional versus diffuse light. Plant Cell Environ. 16 65–72. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1993.tb00845.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelmann T. C., Nishio J. N., Smith W. K. (1996). Leaves and light capture: light propagation and gradients of carbon fixation within leaves. Trends Plant Sci. 1 65–70. 10.1016/S1360-1385(96)80031-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner G. P., Altenberg L. (1996). Perspective: complex adaptations and the evolution of evolvability. Evolution 50 967–976. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb02339.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westoby M., Falster D. S., Moles A. T., Vesk P. A., Wright I. J. (2002). Plant ecological strategies: some leading dimensions of variation between species. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 33 125–159. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.010802.150452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Westoby M., Reich P. B., Wright I. J. (2013). Understanding ecological variation across species: area-based vs mass-based expression of leaf traits. New Phytol. 199 322–323. 10.1111/nph.12345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright I. J., Reich P. B., Westoby M., Ackerly D. D., Baruch Z., Bongers F., et al. (2004). The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 428 821–827. 10.1038/nature02403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. L., Zhang S. B., Chen Y. J., Zhang Y. P., Poorter L., Bonser S. (2015). Nutrient resorption is associated with leaf vein density and growth performance of dipterocarp tree species. J. Ecol. 103 541–549. 10.1111/1365-2745.12392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zwieniecki M. A., Boyce C. K. (2014). Evolution of a unique anatomical precision in angiosperm leaf venation lifts constraints on vascular plant ecology. Proc. Biol. Sci. 281:20132829 10.1098/rspb.2013.2829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]