Abstract

Background

Postoperative pain is thought to be the single most important factor leading to ineffective ventilation and impaired secretion clearance after thoracic trauma. Effective pain relief can be provided by thoracic epidural analgesia but may have side effects or contraindications. Paravertebral block is an effective alternative method without the side effects of a thoracic epidural. We did this study to compare efficacy of thoracic epidural and paravertebral block in providing analgesia to thoracic trauma patients.

Methods

After ethical clearance, 50 patients who had thoracic trauma were randomized into two groups. One was a thoracic epidural group (25), and second was a paravertebral group (25). Both groups received 10 ml of bolus of plain 0.125% bupivacaine and a continuous infusion of 0.25% bupivacaine at the rate of 0.1 ml/kg/h for 24 h. Assessment of pain, hemodynamic parameters, and spirometric measurements of pulmonary function were done before and after procedure. Visual analog scale (VAS) scores were accepted as main outcome of the study and taken for power analysis.

Results

There was significant decrease in postoperative pain in both the groups as measured by VAS score. However, the degree of pain relief between the groups was comparable. There was a significant improvement in pulmonary function tests in both the groups post-procedure. The change in amount of inflammatory markers between both the groups was not significantly different.

Conclusion

Paravertebral block for analgesia is comparable to thoracic epidural in thoracic trauma patients and is associated with fewer side effects.

Keywords: Continuous thoracic epidural, Thoracic trauma, Advanced trauma life support (ATLS)

Introduction

Thoracic trauma causes significant pain and mortality in the perioperative period.1 Postoperative pain after thoracic trauma contributes to atelectasis, pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, and increased intensive care admissions. Poor pain management leads to delayed mobilization, which is associated with increased pooling of secretions in the lungs and impaired ventilation.2 Patients undergoing thoracic procedure may suffer from severe postoperative pain, if analgesia is not managed appropriately. Conversion to chronic pain and post-surgical fatigue after thoracotomy is more, if acute pain is not treated adequately at presentation. There is a significant improvement in pulmonary function and reduced risk for infection and complication in cases of thoracic trauma treated with appropriate analgesia and physiotherapy.2 Hence it is only imperative to consider pain management early in the course of management of thoracic trauma to improve outcomes and speedup recovery.3, 4, 5

Trauma, surgery or any infection in ICU is associated with release of cytokines, which contribute to the development of hemodynamic instability and metabolic derangement, which can worsen prognosis.6 Interleukin (IL)-6 is the most common cytokine shown to be associated with degree of tissue insult and hence can act as surrogate for intensity of tissue damage following trauma.7 The efficacy of utilizing different modalities for analgesia in controlling extent of tissue damage can be compared by measuring these cytokines levels.

The “gold standard” for treatment of postoperative pain following thoracotomy is thoracic epidural. However, in certain situations, there is a need for an alternate mode of analgesia. The other techniques available for pain management post-thoracotomy include paravertebral block, intercostals nerve block, subarachnoid administration of opioids and intrapleural analgesia.2, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10 However, the single best method for pain relief has not been established and these techniques have shown to provide good analgesia and are still under research. A systemic review, the Procedure-Specific Postoperative Pain Management task force, has been formed with aim to develop recommendation for management of postoperative pain following surgery.11, 12 This task force will guide clinicians in selecting appropriate pain management strategies for chest trauma and encourage more studies and trial in pursuit of the best analgesic modality.

The present study was conducted to assess the quality of pain relief and quantity of improvement of pulmonary functioning in patients of thoracic trauma receiving either continuous thoracic epidural analgesia (CTEA) or thoracic paravertebral block (TP). The primary objective was to compare pain scores at 24 h. The secondary objectives were to assess the improvement in pulmonary function tests, the level of inflammatory mediators between the groups. The hypothesis of this study could be termed as there will be improvement of pain scores, pulmonary functions in both the groups equally.

Material and methods

Population

The study was initiated after obtaining ethical clearance from institutional ethics committee. Previous studies on comparison of pain relief between both the methods showed a mean visual analog scale (VAS) score of 3.6 ± 1.44 in paravertebral group and 3.5 ± 2.75 in thoracic epidural group.13 The sample size was calculated as 19 in each group keeping the power of the study as 80% and level of significance at 0.05 and acceptable difference in mean scores as 2 using OpenEpi (www.OpenEpi.com).14

Inclusion criteria

All patients admitted to trauma center or intensive care unit with thoracic trauma who received epidural or paravertebral block for pain relief. The following traumas were considered

-

i.

Patients with multiple rib fractures.

-

ii.

Patients with flail chest and paradoxical respiration.

-

iii.

Patients with contusion of lung.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with bilateral chest trauma, injuries to peripheries, unstable hemodynamics, sensitivity to local anesthetic drugs, infection at the operation site, cardiac dysfunction, renal dysfunction, coagulation abnormalities and patients on opioids were excluded from the study. Patients having psychosocial problem or not cooperative in between the study were also excluded.

Methodology

Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocol was followed for initial assessment and resuscitation.

Study population

A total of 188 patients were admitted during 22 months study period and were screened to be part of the study. A total of 50 patients of either sex in American Society of Anesthesia (ASA) grade I and II, aged 15–60 years suffering from thoracic trauma and received either a thoracic epidural or paravertebral block for pain relief were part of this study (Fig. 1). A written informed consent was obtained before including the patients in to the study. The study protocol was explained to all patients along with VAS after enrollment in to the study.

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram.

Epidural group (Group 1; n = 25)

Under strict aseptic precautions with patient in sitting or lateral position, skin was infiltrated with local anesthesia, and 18 G Tuohy's needle was introduced at T5–T7 level. After obtaining loss of resistance, 20 G epidural catheter was threaded and fixed on skin. After a test dose and a negative aspiration for blood or CSF, 10 ml of 0.125% bupivacaine was given as bolus. Analgesia was maintained postoperatively for 24 h by infusion of 0.25% bupivacaine at a rate of 0.1 ml/kg/h immediately after receiving the patient in ICU.

Paravertebral group (Group 2; n = 25)

Under strict aseptic precaution with patient in prone or sitting or lateral position in a kyphotic posture, spinous processes corresponding to T5 and T7 dermatomes were marked. Under local anesthesia, needle was introduced 2.5 cm laterally till the transverse process was hit. At this point, the needle was removed till the skin and redirected till a loss of resistance was felt. A 20 G thoracic catheter was inserted into about 2–3 cm depth in the paravertebral space. 10 ml of 0.125% bupivacaine was given as bolus. Analgesia was maintained for 24 h by infusion of 0.25% bupivacaine at a rate of 0.1 ml/kg/h. Unilateral loss of sensation was checked to confirm correct catheter placement. Loss of sensation to pin prick and ice bag was used to determine the upper and lower limits of analgesia. Sensory dermatome level was taken as two dermatomes for each vertebral level on either side. Right or left side blockade was assessed.

A resident blinded to the modality of analgesia assessed the pain score before the procedure and every 2 h for the next 24 h till the patient received continuous infusion of bupivacaine. Pain was assessed using VAS score from 0 to 10, where 0 = no pain and 10 = the worst imaginable pain using a 100-mm VAS.15 Patient was considered pain free if VAS < 3. Tramadol 50 mg was given as rescue analgesia to patients with VAS > 3 or on demand. Ramsay sedation scale was used to assess anxiety and sedation during the same time as pain recording. A score is denoted according to patient's level of sedation or anxiety.16

The hemodynamic variables were recorded before, 20 min after the bolus dose of bupivacaine and at 6 h, 12 h, 24 h after catheter placement. Hypotension was defined as mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) less than 65 mmHg. Any hypotension was treated by discontinuation of bupivacaine infusion, elevation of lower limbs and 500 ml bolus of 0.9% NaCl. If no response was obtained to the initial resuscitation, ephedrine 3 mg boluses were given titrated to effect.

Spirometer was used to assess pulmonary function was assessed before and 24 h after procedure and FEV1, FVC and FEF25–75 was recorded.

Patients were monitored every 2 h for 24 h for any adverse effects such as difficulty in breathing or allergic reactions, itching, drowsiness, nausea or vomiting. These adverse effects were graded depending upon sign and symptom as follows: 1 mild, 2 moderate, 3 severe. The highest grade was taken for data analysis. Patients received pharmacological or non-pharmacological treatment based on the severity of symptoms.

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and IL-6 were measured pre-procedure, 6 h and 12 h following CTEA or TP.

The catheters were removed 24 h later, and the analgesic treatment was switched to parental or oral analgesics.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered and tabulated. SPSS version 21 was used to analyze data. Data were expressed as mean ± SD for continuous data with normal distribution. Non-normal data were expressed as median value. Qualitative variables were presented as percentage. Unpaired student t test and Mann–Whitney U test were used to compare continuous data. Fischer exact test and Chi square test were used for qualitative variable. ANOVA was used for inter and intragroup comparison of pulmonary functions pre and post-procedure. A P < 0.05 was taken as significant.

Results

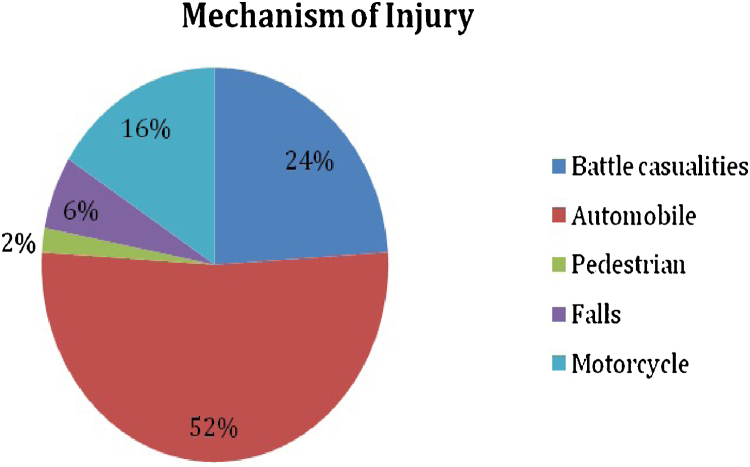

Between July 2011 and May 2013, 188 patients were admitted to ICU and acute trauma ward as case of thoracic trauma. The majority of patients had blunt chest trauma with other associated injuries. The cause for injury was varied as given in Fig. 2. Nearly half of the patients with thoracic injury (47.5%) had associated other system involvement emphasizing on the severity and morbidity associated with thoracic trauma. Both the groups showed no difference with respect to age, weight and duration of epidural catheter (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Cause of injury (expressed as percentage).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Epidural group (25) | Paravertebral group (25) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 36 (18–42) | 34.5 (20–46) | >0.05 |

| Sex (M:F) | 16:9 | 19:6 | >0.05 |

| Weight | 66.9 ± 13.6 | 69.7 ± 13.9 | >0.05 |

| Duration of epidural catheter (days) | 2.1 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | >0.05 |

| Total number of attempts to place catheter | 31 | 44 | >0.05 |

Mean ± SD, median (range).

Thoracic paravertebral catheter was successfully placed in all patients. However, the technical difficulty for insertion varied from patient to patient. In fourteen patients, multiple attempts were required, in twelve patients, there was resistance encountered during insertion, and in seven cases it was easily inserted. Bloody tap was obtained in seven patients, who were managed with change of direction of needle tip or by flushing catheter with saline. Multiple attempts were required in the placement of epidural catheter in seven cases (Table 1). Adverse events such as paraesthesia, pain, intrathecal spread, pleural puncture, pneumothorax, and hematoma during needle or catheter insertion were not reported by the patients in either group.

The median VAS score reduced from 8 in the immediate postoperative period to 5 after 4 h in both the groups. The respective postoperative pain in both groups was reduced compared to baseline (P < 0.0001). There was a significant reduction in pain measured at all time points postoperatively, when compared with the immediate postop period in both the groups. However the modality of pain management did not affect the decrease in pain, and both the groups were comparable as expressed as area under the curve (epidural group: mean area – 582, SD – 60; paravertebral group: mean area – 585.5, SD – 65.17), P value >0.05 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

VAS score comparison between the groups.

There was a significant lowering of mean arterial pressure and improvement of FEV1, FVC, FEF25–75 in both groups compared to initial values. However, there was no difference in hemodynamic variables such as heart rate and MAP between both the groups at 24 h (Fig. 4, Fig. 5). However, intragroup comparison showed that there was a decrease in MAP compared to preinsertion values, which was significant in both the groups (P < 0.05). There was no change in levels of inflammatory markers in either group (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Pulmonary function before and after intervention between the groups.

Fig. 5.

Hemodynamic parameters before and after procedure between the groups.

Table 2.

Inflammatory markers.

| Epidural group (25) | Paravertebral group (25) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | |||

| Preprocedure | 102.2 ± 10.2 | 106.5 ± 7.6 | >0.05 |

| After 6 h | 102.7 ± 12.2 | 105.7 ± 10.2 | >0.05 |

| After 24 h | 96.2 ± 6.8 | 98.7 ± 8.3 | >0.05 |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | |||

| Preprocedure | 114 ± 9.6 | 112 ± 8.5 | >0.05 |

| After 6 h | 112 ± 8.6 | 108 ± 7.5 | >0.05 |

| After 24 h | 98.2 ± 10.2 | 102.5 ± 7.6 | >0.05 |

Mean ± SD.

Discussion

Post-thoracic trauma causes significant pain, which delays recovery and contributes to significant morbidity.1 Effective pain management is the cornerstone in thoracic trauma, leading to better outcomes and improved pulmonary functions. Hence anesthesiologists have a significant role in the treatment of thoracic trauma.

Thoracic epidural vs paravertebral block for pain management in cases of chest trauma was compared in this study. Till date, there is no single technique, which is shown to be superior to other techniques for pain management in thoracic trauma. Guidelines are yet to be formulated for grading pain and its management in trauma. Few studies have shown the superiority of thoracic paravertebral block (PVB) in providing post-thoracotomy analgesia and improving lung function when compared with systemic opioids or intrapleural block.2 For severe pain, regional anesthestic techniques seem to be superior to all other pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods. However, there are limited well-conducted trials comparing varied regional pain management methods for post-thoracotomy pain.

The present study compared the analgesic efficacy, hemodynamic variables, pulmonary functions and inflammatory markers in blood between continuous thoracic epidural and paravertebral block.

There are various studies comparing different types, concentration and volume of local anesthetics used for regional block. However, the lowest effective concentration in literature was used in the present study to avoid any adverse effects of the drug and due to the lack of resources to monitor blood levels of local anesthetic.12, 17, 18, 19, 20 There was demonstrable reduction in VAS scores in both the groups in spite of using a lower concentration of local anesthetic. The pain relief provided by both the techniques was comparable, but superiority of one technique over other was not evident. This further emphasizes the fact that both techniques are useful for pain relief, and the selection of technique should depend on the patient profile, clinical scenario, and expertise of the anesthesiologist in the regional technique available.

Both the groups showed a decrease in blood pressure compared to the baseline values despite adequate hydration and using lower dosage of local anesthetic. The bilateral sympathetic block following thoracic epidural can be attributed to hypotension.11, 17, 19 Studies have shown a lower incidence of hypotension in paravertebral blocks in comparison with epidural similar to findings of the present study.12 There was a reduction in heart rate more epidural anesthesia group as compared to paravertebral group. There was significant improvement of pulmonary function in both the groups in comparison to pre-procedure values. This states and reinforces the relation between adequate analgesia and pulmonary functions. Hence to enable adequate and early rehabilitation and better lung function effective pain management is essential. In this study, both the methods were found to be equally effective in improving pulmonary outcomes.

Cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α play an important role in modulating hemodynamic response. It is also been shown to cause hyperalgesia. The exact mechanism for hyperalgesia is yet to be eluded; however, there is a possibility that it acts by altering the excitability of pain fibers. Cytokines are surrogate markers for tissue injury and can correlate with the magnitude of injury.2, 7 The IL-6 and TNF-α levels in the both groups (epidural or paravertebral group) before the procedure was significantly higher and gradually diminished after the procedure. This is corroborative to previous studies, which showed correlation between pain and rise in cytokine levels. This further ascertains the need for adequate analgesia following trauma to prevent the ill effects of cytokines and hasten recovery. The levels of TNF-α and IL-6 were low after procedure in both groups and were comparable. This reemphasizes that both methods of analgesia are equally effective in pain control.

The study was not a randomized controlled study, so observation bias could not be eliminated. Blinding was not done in the study because of the obvious difference in methods used. A well-controlled randomized study is required to compare the superiority of technique. This study was not designed to compare the advantages or complications between both the techniques of analgesia.

Conclusion

There are various aspects of pain management, which need to be considered in thoracic trauma. Analgesia should be an integral part of management of thoracic trauma. Presently, the modality of choice for post-thoracotomy pain has not been established. Thoracic epidurals have been considered as gold standard for post-thoracotomy pain and paravertebral blocks is a promising alternative for analgesia in cases, where epidurals are a contraindication or difficult. Adequate pain relief is central to treatment of thoracic trauma and is likely to improve hemodynamic and pulmonary function. Hence all patients of thoracic trauma should be offered a modality for pain management, and the selection of technique should be tailored to the needs, availability and expertise of the anesthesiologist involved.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on Armed Forces Medical Research Committee Project No. 4198/2011 granted and funded by the office of the Directorate General Armed Forces Medical Services and Defence Research Development Organization, Government of India.

References

- 1.Richardson J., Sabanathan S., Shah R. Post-thoracotomy spirometric lung function: the effect of analgesia. A review. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;40(3):445–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballantyne J.C., Carr D.B., deFerranti S. The comparative effects of postoperative analgesic therapies on pulmonary outcome: cumulative meta-analyses of randomized, controlled trials. Anesth Analg. 1998;86(3):598–612. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199803000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katz J., Jackson M., Kavanagh B.P., Sandler A.N. Acute pain after thoracic surgery predicts long-term post-thoracotomy pain. Clin J Pain. 1996;12(March (1)):50–55. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199603000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gotoda Y., Kambara N., Sakai T., Kishi Y., Kodama K., Koyama T. The morbidity, time course and predictive factors for persistent post-thoracotomy pain. Eur J Pain. 2001;5(1):89–96. doi: 10.1053/eujp.2001.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gottschalk A., Cohen S.P., Yang S., Ochroch E.A. Preventing and treating pain after thoracic surgery. Anesthesiology. 2006;104(3):594–600. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200603000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dajczman E., Gordon A., Kreisman H., Wolkove N. Long-term postthoracotomy pain. Chest. 1991;99(2):270–274. doi: 10.1378/chest.99.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nagahiro I., Andou A., Aoe M., Sano Y., Date H., Shimizu N. Pulmonary function, postoperative pain, and serum cytokine level after lobectomy: a comparison of VATS and conventional procedure. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72(August (2)):362–365. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02804-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tiippana E., Nilsson E., Kalso E. Post-thoracotomy pain after thoracic epidural analgesia: a prospective follow-up study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47(4):433–438. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.00056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joshi G.P., Bonnet F., Shah R. A systematic review of randomized trials evaluating regional techniques for postthoracotomy analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2008;107(3):1026–1040. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000333274.63501.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helms O., Mariano J., Hentz J.-G. Intra-operative paravertebral block for postoperative analgesia in thoracotomy patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40(4):902–906. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soto R.G., Fu E.S. Acute pain management for patients undergoing thoracotomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75(4):1349–1357. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04647-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eason M.J., Wyatt R. Paravertebral thoracic block – a reappraisal. Anaesthesia. 1979;34(7):638–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1979.tb06363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grider J.S., Mullet T.W., Saha S.P., Harned M.E., Sloan P.A. A randomized, double-blind trial comparing continuous thoracic epidural bupivacaine with and without opioid in contrast to a continuous paravertebral infusion of bupivacaine for post-thoracotomy pain. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2012;26:83–89. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sullivan K.M., Dean A., Soe M.M. OpenEpi: a web-based epidemiologic and statistical calculator for public health. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(3):471–474. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCormack H.M., Horne D.J., Sheather S. Clinical applications of visual analogue scales: a critical review. Psychol Med. 1988;18:1007–1019. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700009934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dawson R., von Fintel N., Nairn S. Sedation assessment using the Ramsay scale. Emerg Nurse. 2010;18(3):18–20. doi: 10.7748/en2010.06.18.3.18.c7825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies R.G., Myles P.S., Graham J.M. A comparison of the analgesic efficacy and side-effects of paravertebral vs epidural blockade for thoracotomy – a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2006;96(4):418–426. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berrisford R.G., Sabanathan S.S., Mearns A.J., Bickford-Smith P.J. Pulmonary complications after lung resection: the effect of continuous extrapleural intercostal nerve block. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1990;4(8):407–411. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(90)90068-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freise H., Van Aken H.K. Risks and benefits of thoracic epidural anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107(6):859–868. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kotzé A., Scally A., Howell S. Efficacy and safety of different techniques of paravertebral block for analgesia after thoracotomy: a systematic review and metaregression. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103(5):626–636. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]