Abstract

Background

Infantile esotropia is a convergent strabismus presenting before 6 months of age and is the most common strabismus disorder presenting in the ophthalmology OPD. The dilemma of whether to go for early surgery and how early has been a matter of research for the last 50 years. We describe our results of surgery in infantile esotropia at variable age groups, as well as with different reoperation rates and compare with the results in western literature.

Methods

A prospective study was carried out through a review of 113 cases operated for infantile esotropia between February 2013 and August 2014. The variables studied were: age at surgery, type of fixation, refractive error, associated nystagmus, inferior oblique overaction or dissociated vertical deviation (DVD), type of surgery performed and pre- and postoperative deviation angles.

Results

There were 67 male and 46 female cases of infantile esotropia. The age group of patients varied from 6 months to 12 years. Latent nystagmus was seen in 22 cases, inferior oblique overaction in 49 cases and DVD (mild) in 14 cases. Bimedial rectus recession was done in 78 cases and recession–resection in non-dominant eye in remaining 35 cases. The postoperative residual deviation was <10 PD in 102 cases, between 10 and 16 PD in 5 cases and more than 16 PD in 6 cases. Only 6 cases (5.3%) required reoperation for correction of residual deviation.

Conclusion

The authors recommend surgery before 12 months in all cases of infantile esotropia. The reoperation rates in the current study were considerably low.

Keywords: Early surgery, Infantile esotropia, Reoperation

Introduction

Convergent deviation in childhood is the most common strabismus disorder which presents in the ophthalmology clinics worldwide. It affects 1–2% of children. The term congenital or infantile esotropia has been debated for over five decades now. Costenbader advocated ‘Congenital’ esotropia for all cases1 manifesting before 6 months and Von Noorden preferred the term ‘infantile esotropia’.2 Various studies by Nixon and Archer failed to provide a concrete data on number of actual esotropes in infants below 4 months.3 But there seems to have emerged a uniform consensus that unsteady ocular motor behaviour along with absent stereo-response are found in normal infants before 4 months of age.

The characteristics of congenital esotropia agreed upon are, age of onset by 6 months, large angle esotropia, cross fixation, normal neurological status, hyperopia as per age not influencing esotropia, nystagmus in few cases.4

The optimum age for surgery in infantile esotropia has fluctuated over the last four decades with an increasing trend towards early surgery. Although there is still no unanimous consensus as to the exact age when infantile esotropia is to be addressed, yet there is recognition that even subnormal binocularity can be achieved only if surgical alignment is achieved.4, 5, 6, 7, 8

Very few studies have been done in India on the results of early surgery in infantile esotropia due to various factors like deep rooted beliefs on either late surgery or no surgery particularly in rural areas. However, lately there has been an increase in the referral of strabismus cases due to an increased awareness. Our centre, being a tertiary apex centre, has had a number of cases of strabismus over the last year, hence a study on the early surgical alignment in infantile esotropia is bound to generate valuable insight into the outcome of early surgery in infantile esotropia.

Material and methods

A prospective study was conducted to record the outcome of infantile esotropia cases operated between February 2013 and August 2014 at our tertiary care centre in North India. A total of 113 cases were included in the study. The minimum period of follow up was 6 months. Our study had 67 males and 46 female cases of infantile esotropia. The age group was variable between 6 months and 12 years.

The inclusion criterion was defined as deviation angle more than 40 PD, no neurological involvement. Only cases with refraction < 3D hyperopia under atropine were included. Children who developed esotropia after 12 months of age, restrictive or paralytic strabismus, accommodative esotropia, children with neurological disorders and optic nerve anomalies were excluded. Children not cooperative for Randot stereoacuity test were excluded from the study.

Surgery was performed by a single surgeon through fornix approach. Bimedial rectus recession was done in 106 cases and horizontal rectus recess–resect in 7 cases. Graded Inferior oblique recession was done depending on severity of overaction.

The variables analysed were: age at surgery, duration of deviation, sex, refractive error, inferior oblique overaction, dissociated vertical deviation (DVD), nystagmus, type of surgery performed and pre- and postoperative deviation angles. Standard protocol for squint examination was followed:

-

•

Presenting symptom: duration of deviation, age of onset, associated symptoms. Previous treatment was undertaken like occlusion or optical glasses.

-

•

Vision was recorded differently in various age groups. From 6 months to 1 year, the methods used were fixation and follow, CSM fixation (central, steady and maintained) and VEP. For children from 1 year to 3 years Allen picture card and Cardiff acuity cards and for children above 3 years Landolt's C chart or Albini's E chart.

-

•

Retinoscopy was done under atropine in all cases.

-

•

Slit-lamp examination of the anterior segment, and fundus examination was done.

-

•Orthoptic work up was done which included:

-

∘Head posture

-

∘Cover test for distance and near

-

∘Ocular movements

-

∘Presence of nystagmus

-

∘Measurement of deviation with Hirschberg test (in children below 3 years) and Prism bar cover test (in children above 3 years)

-

∘Cover test

-

∘Measurement of stereopsis with randot stereoacuity charts

-

∘

-

•

The outcomes studied included postoperative alignment, amblyopia and binocularity function. Postoperative alignment was followed up for two years following surgery with cover and uncover test, amblyopia was assessed based on the different age groups (Cardiff acuity cards for children below 3 years, Landolt’ C chart for cases above 3 years) and binocularity using Randot stereoacuity charts.

The study was approved by the hospital Ethics Committee. Data were obtained from clinical records maintaining patient anonymity. Data analysis was done using Excel 2003, and the different qualitative variables were analysed.

Results

There were a total of 113 cases with 67 male and 46 female cases of infantile esotropia. The age group of patients varied from 6 months to 12 years. There were 82 children in 6 month to 1-year age group, 16 in 1–2 year group, 7 in 2–3 year group, 5 in 4–8 year group and 3 in 8–12 year group (Table 1). Compared to western literature, the age of presentation of infantile esotropia was varied, and there were cases presenting even beyond 2 years.

Table 1.

Distribution of age in infantile esotropia cases at presentation.

Duration of deviation was equal to the age at presentation as all the cases had history of manifest deviation before 6 months of age. Free alternation of vision was present in 78 cases (amblyopia in remaining 35 cases from different age groups) (Table 2). Vision testing method was different in groups as the age varied from 6 months to 12 years.

Table 2.

Vision at presentation in our series of infantile esotropia children.

| Log MAR equivalent visual acuitya | No. of cases |

|---|---|

| 0.0 to <0.2 | 78 |

| 0.2 to <0.6 | 13 |

| 0.6 to <1.0 | 8 |

| >1.0 | 14 |

Vision was recorded with Cardiff acuity cards for children below 3 years, Landolt’ C or Albini's E chart for cases above 3 years and converted to Log MAR equivalent.

Only cases with refraction below 3 diopter were taken. Refraction was between +1.5 and +3 diopter in all cases. The preoperative deviation in all cases was more than 40 prism diopter (PD). Latent nystagmus was seen in 22 cases, inferior oblique overaction was seen in 49 cases (mild in 33 cases, moderate in 12 cases and severe in 4 cases). DVD (mild) was seen in 14 cases (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associated anomaly with infantile esotropia.

The cases were planned for early correction; bimedial rectus recession in 78 cases (69.02%) and recession and resection in non-dominant amblyopic eye in remaining 35 cases (30.97%). Inferior oblique (IO) recession was carried out based on degree of overaction. The postoperative residual deviation was <10 PD in 102 cases, between 10 and 16 PD in 5 cases and more than 16 PD in 6 cases (Table 4).

Table 4.

Post operative results in infantile esotropia cases.

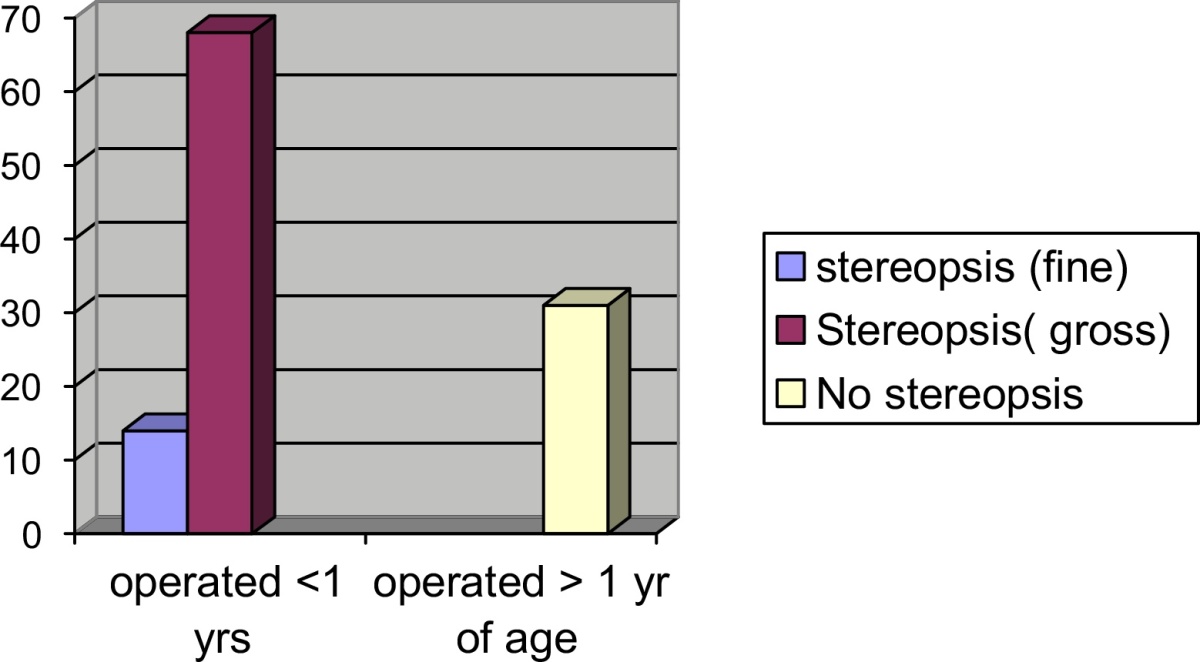

Outcome of 82 cases of infantile esotropia operated before one year of age was compared to 31 cases operated beyond one year of age. The cases, who had presented beyond one year of age had waited for seeking medical attention due to various causes like misinformation, false beliefs or misguidance. All the cases had subnormal gross stereopsis before surgery. Fourteen cases (17%) operated before one year of age demonstrated fine stereopsis within 6 months of surgery on follow-up. Rest of the cases operated before one year of age showed only gross stereopsis whereas all the cases operated beyond one of age had no stereopsis (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of stereopsis in cases operated before one year of age and cases operated beyond one year of age.

Six cases (5.3%) were taken up for reoperation for correction of residual deviation in the follow up period after 3 months from initial surgery. Out of these 3(2.65%) were below one year age group, 1(0.8%) in 1–2 year age group and 2(1.7%) in 2–3 year age group. All these cases had initial deviation more than 60 prism diopter and maximal bimedial rectus recession did not give adequate results. Additional resection of lateral rectus was planned on non-dominant eye. All these 6 cases had amblyopia and latent nystagmus in the deviating eye.

The 35 cases detected with amblyopia were further followed up with occlusion therapy for varying periods from 6 months to 2 years with marginal improvement in 21 cases.

Discussion

Congenital esotropia mostly appears to be caused by defective development of fusion (Worth's hypothesis) which is evident in many patient's failure to achieve normal binocularity although gross stereopsis has been recorded and in few cases even fine stereopsis. Even environmental factors contribute to a high frequency of strabismus and amblyopia as is evident in low birth-weight and premature infants, and those suffering perinatal hypoxia. Smoking, drugs and alcohol abuse during pregnancy also disrupt brain development and are closely associated with amblyopia and strabismus.1, 2, 3, 4, 11

Costenbader had adequately defined infantile esotropia as strabismus presenting by 6 months of age with a large deviation and unresponsive to spectacle treatment of hyperopia if present.1 He further elucidated that only 20% patients of infantile esotropia fail to attain fusion following early treatment which was in clear contrast to the statement by Berke where he had stated that no congenital esotrope can obtain stereopsis and thus no cure is possible. It was Taylor who in the first published study on stereopsis following surgery reaffirmed that binocularity is possible if surgery is done before 2 years of age and the residual deviation is less than 10 PD.4 Von Noorden initially had challenged the concept of operating as early as 6–12 months of age due to a contention that it will lead to a high number of overcorrections and undercorrections.2

Banks et al. in 1974 studied 24 persons with subnormal binocularity caused by esotropia and tested them for interocular transfer of tilt after effect and concluded that the sensitive period for the development of binocularity begins several months after birth and peaks between one and three years of age and that early corrective surgery in infantile esotropia could lead to development of cortical binocularity.5

Helveston had advocated 4 months as the earliest age for congenital esotropia surgery. He found equivalent predictable results in cases operated at 4 months and those operated at 12 months of age. In the present study, surgical alignment was satisfactory in 6 month to one year age group; however, no case was operated before 6 months of age.

While authors still disagree on optimal age for surgery, Prieto-Díaz et al. suggested that the earlier ocular alignment is achieved, the better the functional result attained. He studied 123 surgically-aligned cases aged >4 years. Of these, 108 (87.8%) showed fusion (assessed using Bagolini striated lenses); and 92 (74.8%) a degree of stereopsis (assessed by Titmus test).6

The European Early vs. Late Infantile Strabismus Surgery Study (ELISSS) was done to compare early and late surgery groups. In that study 13.5% of children operated around 20 months vs. 3.9% (P = 0.001) of those operated around 49 months had gross stereopsis (Titmus Housefly) at age 6. In our study due to the varied age group this factor could not be compared. The reoperation rate was 28.7% in children operated early vs. 24.6% in those operated late. Unexpectedly, 8% in the early group vs. 20% in the late group had not been operated at age 6, although all had been eligible for surgery at baseline at 11 SD 3.7 months. In most of these children the angle of strabismus decreased spontaneously. In a meta-regression analysis of the ELISSS and other studies we found that reoperation rates were 60–80% for children first operated around 1 year of age and 25% for children operated around 4 years of age. In our study 6 cases (5.3%) were taken up for reoperation for correction of residual deviation in the follow up period.7 There was no significant difference in reoperation rate in cases operated before 12 months of age and those operated beyond 12 months of age.

Bilateral medial rectus recession is usually done for the infantile esotropia which are alternators however in case of dominance of one particular eye recession and resection of non dominant eye is preferred.4, 8, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15 The extent of bimedial recession is generally calculated based on Hirschberg test as prism bar cover test is not possible in infants. The present analysis describes the surgical results in infantile esotropia cases treated at our tertiary care hospital between February 2013 and August 2014. The results show bimedial rectus recession was most effective in correction of infantile esotropia. The results of surgery were comparably better as only 5.3% of cases had to undergo reoperation as compared to 30–40% in various studies.11, 12, 13 Inferior oblique recession further improved the results in cases with IO overaction.

Calcutt studied 113 cases of untreated congenital esotropia and found that 72% showed oblique muscle overaction and 57% showed DVD.15 In our study, the common associations with infantile esotropia were inferior oblique overaction (43.36%), nystagmus (19.46%), DVD (12.48%) consistent with other studies.7, 14, 15, 16

In our study, preoperative deviation angle was more than 40 PD in all cases. Acceptable results of deviation less than 10 PD were achieved in 102 cases (90.26%) and between 10 and 16 PD in 5 cases (4.4%) which was considered adequate correction as the vision was equal in both eyes and there was no amblyopia, in addition the parents were satisfied with the cosmetic result. The results are better as compared to most of the studies which give 60–80% results with a higher reoperation rate of 30–40% (vis a vis 5.3% in our study).12, 13, 14, 15 The possible reason for a higher success rate could be evaluation on standardized scale where all aspects of limitation of movement, dominance of eye, inferior oblique overaction and nystagmus was taken into consideration. In cases where the inferior oblique overaction was apparent simultaneous correction was planned.

Assaf in a study compared early vs. late alignment in infantile esotropia. Out of 101 operated children, the esotropia in 70 patients was aligned to within 10 prism diopters. The patients with successful alignment were reviewed to study the effect of early vs. late surgical intervention of their deviation, i.e. before and after two years of age. The motor and sensory states of the selected patients were analyzed before and after surgical correction. The study concluded that patients two years and older though had a good chance of alignment, but had less chance of attaining binocularity. In comparison, the younger group with earlier surgery appeared to show a better chance of attaining binocularity.16 Our study had also shown attainment of binocularity in 14 cases (17.82%) operated before one year of age as compared to none in cases operated after one year of age.

Vasseneix et al. in a study on comparison of surgery results when the intervention takes place before or after 30 months of age17 found no significant advantage of early surgery vs. surgery after 30 months of age.

Simonsz et al. in 2011 had mentioned about the differences in age for early surgery in European countries (2–3 years) as compared to US (12–18 months).18 They stressed that the best age for surgery in a child with infantile esotropia should be: (1) degree of binocular vision restored or retained, (2) postoperative angle and long-term stability of the angle and (3) number of operations needed or chance of spontaneous regression. The present study does show restoration of stereopsis in 14 cases (17%) and would thus recommend early surgery before 12 months of age.

In our study the major limitation was that the number of cases operated before one year of age were more than those taken beyond one year of age and so no direct comparison of the two groups were possible, hence statistically not significant. However, this was a retrospective study of the number of cases of infantile esotropia presenting over one year at the tertiary care centre, who were operated and followed up for two years.

There were a substantial number of cases referred late for surgery due to various causes. The socio-cultural milieu of this region in Northern India and long standing myths surrounding strabismus is the primary cause for such late referrals. There is a definite need for increasing awareness amongst the general population about the complications of delayed surgery including severe amblyopia where visual prognosis is guarded.

Conclusions

Outcome of early correction before one year of age in infantile esotropia showed improvement in stereopsis in all cases (17% cases had fine stereopsis and 83% had gross stereopsis), whereas none of the case operated beyond one year of age developed even gross stereopsis. Owing to the major limitation of more number of cases in below one year age group, statistical significance cannot be commented upon but the results do show corroboration with earlier landmark studies.

We, therefore, recommend surgery before 12 months in all cases of infantile esotropia. The benefit of attaining stereopsis in early surgery should be considered as a primary objective to attain a more stable alignment after surgery. In addition infantile esotropia hampers normal social and psychological development of the child, and this is also a major factor for early surgical correction.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Costenbader F.D. Infantile esotropia. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1961;59:397–429. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Noorden G.K. A reassessment of infantile esotropia. XLIV Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;105:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helveston E.M. 19th annual Frank Costenbader Lecture-the origins of congenital esotropia. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1993;30:215–232. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19930701-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor D.M. How early is early surgery in management of strabismus. Arch Ophthalmol. 1963;70:752–756. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1963.00960050754006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banks M.S., Aslin R.N., Letson R.D. Sensitive period for the development of human binocular vision. Science. 1975;190:675–677. doi: 10.1126/science.1188363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prieto-Diaz J., Souza-Diaz C. 5th ed. Científica Argentina; Buenos Aires: 2005. Estrabismo; pp. 160–178. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simonsz H.J., Kolling G.H., Unnebrink K. Final report of the early vs. late infantile strabismus surgery study (ELISSS), a controlled, prospective, multicenter study. Strabismus. 2005;13:169–199. doi: 10.1080/09273970500416594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohney B.G., Greenberg A.E., Diehl N.N. Age at strabismus diagnosis in an incidence cohort of children. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:467–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nixon R.B., Helveston E.M., Miller K., Archer S.M., Ellis F.D. Incidence of strabismus in neonates. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;100:798–801. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)73370-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chew E., Remaley N.A., Tamboli A., Zhao J., Podgor M.J., Klebanoff M. Risk factors for esotropia and exotropia. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:1349–1355. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090220099030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ing M.R. Outcome of surgical alignment before 6 months of age for congenital esotropia. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:2041–2045. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30756-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birch E., Stager D., Wright K., Beck R. The natural history of infantile esotropia during the first 6 months of life. JAAPOS. 1998;2:325–328. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(98)90026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright W.K. Esotropía. In: Wright W.K., editor. Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Mosby; St. Louis: 1995. pp. 179–193. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Helveston E.M. 4th ed. Mosby; St. Louis: 1993. Surgical Management of Strabismus: Atlas of Strabismus Surgery. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calcutt C. The natural history of infantile esotropia. A study of the untreated condition in the visual adult. Transactions of the VII International Orthoptic Congress; Germany; 1991. pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Assaf A.A. Early versus late alignment of infantile esotropia. Strabismus. 1995;3:61–69. doi: 10.3109/09273979509063836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vasseneix C., Retout A., Ducrotte D. Infantile esotropia: comparison of surgery results when the intervention takes place before or after 30 months of age. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2005;28:743–748. doi: 10.1016/s0181-5512(05)80987-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Simonsz H.J., Kolling G.H. Best age for surgery for infantile esotropia. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2011;15:205–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]