Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the diagnostic agreement when a general practitioner and subsequently a specialist (radiologist/gynecologist) performed point-of-care ultrasound examinations for certain abdominal and gynecological conditions of low to moderate complexity.

Design

A prospective study of inter-rater reliability and agreement.

Setting

Patients were recruited and initially scanned in general practice. The validation examinations were conducted in a hospital setting.

Subjects

A convenient sample of 114 patients presenting with abdominal pain or discomfort, possible pregnancy or known risk factors toward abdominal aortic aneurism were included.

Main outcome measures

Inter-rater agreement (Kappa statistic and percentage agreement) between ultrasound examinations by general practitioner and specialist for the following conditions: gallstones, ascites, abdominal aorta >5 cm, intrauterine pregnancy and gestational age.

Results

An overall Kappa value of 0.93 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.87–0.98) was obtained. Ascites, abdominal aortic diameter >5cm, and intrauterine pregnancy showed Kappa values of 1.

Conclusion

Our study showed that general practitioners performing point-of-care ultrasound examinations with low-to-moderate complexity had a very high rate of inter-rater agreement compared with specialists.

Keywords: General practitioners, family medicine, ultrasonography, inter-rater reliability, validation, education

Introduction

Traditionally, ultrasound examinations have been a part of the radiology specialty [1]. However, in recent years, other medical specialties have adapted the use of ultrasound examinations in ways relevant for their patient groups. The different specialties have implemented ultrasound examinations in specific and limited areas of their patient examination. For example, cardiologists use ultrasound examination to evaluate function of the heart and gynecologists may obtain structural information about the uterus and ovaries through the use of ultrasound. The different specialties use ultrasound examinations in a focused manner during the clinical examination of their patients. This way of conducting ultrasound examinations is known as a point-of-care ultrasound examination [2].

In Denmark, the use of ultrasound examinations by general practitioners (GPs) is very limited, and currently, there is no economic compensation for performing ultrasound examinations in general practice [3].

One of the challenges involved in implementing ultrasound examinations in general practice is the question of validating the quality of ultrasound examinations performed by GPs. More than 30 years ago, Bratland et al. [4–9] looked into the possibilities of utilizing ultrasound examinations in general practice. Huge advances in ultrasound technology have since made the subject even more relevant to explore. In 2002 and 2007, Wordsworth et al. [10] and Glasø et al. [11], respectively, also looked into the challenges of using ultrasound examinations in general practice. They concluded that GPs need a structured education with certification and a system to keep skills at a sufficient level over time. Indeed, these are some of the same conclusions Bratland et al. reached 30 years earlier. Additionally, they proposed more specific studies into the quality of ultrasound examinations performed by GPs. They emphasized that it is important to choose specific examinations that are more accessible to ensure quality.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the quality of the ultrasound examinations performed by GPs. The study explored the inter-rater agreement between GPs and radiologists/gynecologists within a limited range of ultrasound examinations.

Material and methods

Our study design was inter-rater reliability and agreement with prospective data collection. The study was conducted over a 12-month period from March 2015 to April 2016. Five GPs from five different clinics participated in the study. Four were recognized specialists in family medicine by the Danish Medical Association and one was a final-year resident in the family medicine specialty. None of them had prior formal education in conducting ultrasound examinations. The clinics were all located in or near the city of Odense (Denmark).

To ensure a common base level of ultrasound knowledge among the participating GPs, they were all enrolled in an ultrasound course supplied by the Center of Clinical Ultrasound (CECLUS), University of Aarhus [12]. This course was specifically aimed toward the use of point-of-care ultrasound examinations in general practice. The course consisted of three parts: An e-learning section, educational days and feedback on ultrasound examinations performed by the participants in a period after the educational days. The e-learning part consisted of online lectures ranging from basic ultrasound knowledge such as physics and ultrasound equipment to focused ultrasound examinations of thoracic structures, abdomen, vascular and musculoskeletal examinations. The educational days consisted of two days with hands-on ultrasound examinations in all the fields covered in the e-learning part. During the feedback section of the course, all the participants had to return a range of 25 specific ultrasound examinations to the instructors from CECLUS. The examinations, represented as video sequences and screenshots, should be obtained during the daily work of the participants. They were uploaded to the CECLUS course server for individual feedback from the instructors. Finally, a short practical evaluation/certification was performed at CECLUS.

All five GPs in our study passed this course. Prior to data collection, we defined five different ultrasound examinations to be included in our study (Table 1). The examinations were selected on the grounds of their relevance for general practice, low-to-moderate complexity and the possibility of the examination being repeated by a radiological or gynecological department. All five ultrasound examination types had been a part of the initial CECLUS course.

Table 1.

Point-of-care ultrasound examinations included in the study

| • Gallstones |

| • Ascites |

| • Abdominal aorta >5 cm diameter |

| • Intrauterine pregnancy |

| • Gestational agea |

The study data sheet was noted with ‘yes’ for both examinations (general practice and control examination) if the estimated gestational ages were within three days of each other. Otherwise ‘no’ was noted for the control examination.

During the study period, an ultrasound scanner was placed in each of the five clinics. It was a mid-range portable ultrasound scanner from the producer SonoScape, Model S2, Shenzhen, China. It had color Doppler and was equipped with three probes (curved, linear and endovaginal).

Data were collected during normal working hours in the clinics. Our sampling method was convenient and inclusion criteria were patients representing with symptoms normally indicating referral to ultrasound examinations within the predefined areas. This included patients presenting with upper abdominal pain or discomfort, possible pregnancy or known risk factors toward abdominal aortic aneurism. The patients were scanned by the GP in the clinic and a study data sheet was filled out. The data sheet contained information about the GPs’ conclusions after the examination, time taken to conduct the examination and additional remarks if applicable.

The conclusions were all in the form of yes/no regarding the clinical question that we sought to answer with ultrasound, for example gallstones yes/no. There were no structural or anatomical organ evaluations. We hereby stayed true to the concept of point-of-care ultrasound examination [2]. More than one conclusion could be added per patient if applicable. For example, for a patient with abdominal discomfort, there could be added conclusions for both gallstones and ascites.

The patient was then referred to a department of radiology or gynecology for a control ultrasound examination. The referral text did not contain information about the prior ultrasound examination. It only contained anamnestic information and the result of a basic objective examination and working diagnosis. In this way, the radiologist/gynecologist was blinded to our prior examination result.

Examinations regarding intrauterine pregnancy and gestational age were both referred to a department of gynecology, since these examinations are done by gynecologists and not radiologists in Denmark.

Regarding registration of gestational age, it was agreed to register consistency between the examinations if the examinations conducted by the GPs were within three days of the determined gestational age from the control examinations.

When we got the results back from the referred departments, they were noted on the study data sheet and the results could then be compared.

For statistical evaluation, we primarily used Kappa statistics as our level of measurement was nominal. The advantage of Kappa statistic is its ability to take into account the possibility of two raters agreeing on a result purely by chance [13].

Kappa statistic index values were calculated including the overall inter-rater agreement between the results from the clinics and the hospital control examinations. Table 2 [14] was used to interpret the obtained Kappa values. Percentage agreements, sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV were also calculated. This was done primarily in order to compare our study data with other studies that did not use Kappa statistics. Software programs Excel and STATA 11.ed. were used for the statistical calculations. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency and all patient data was anonymized after the study period.

Table 2.

Kappa value interpretation

| Value of Kappa | Level of agreement |

|---|---|

| 0–.20 | None |

| .21–.39 | Minimal |

| .40–.59 | Weak |

| .60–.79 | Moderate |

| .80–.90 | Strong |

| >.90 | Almost perfect |

Results

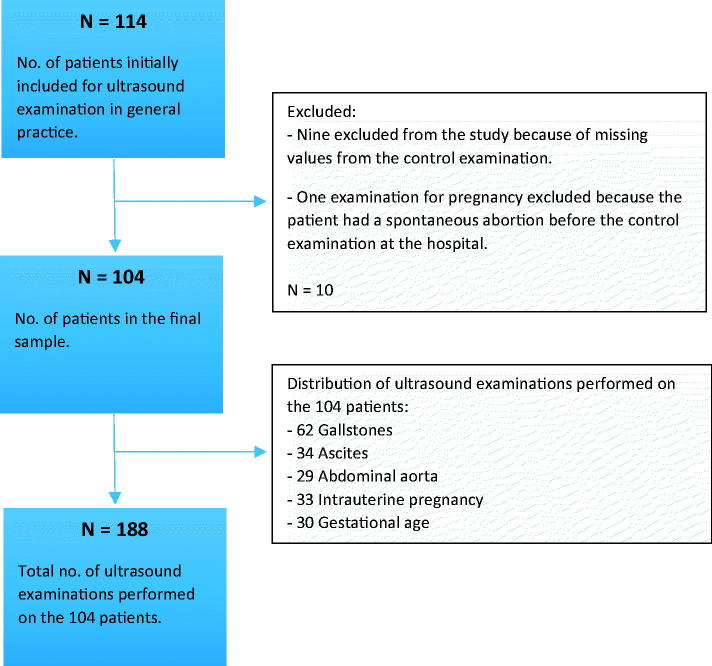

A total of 114 patients were included from the five clinics during the study period. Figure 1 shows the patient flow for the study sampling. Nine were later excluded from the study data because of missing values from the control examination. One examination for pregnancy was excluded because the patient had a spontaneous abortion the day before the control examination at the hospital. Hence, 104 patients were then included in the final results with sample characteristics of 39% male and 61% female. Average age was 48 years (ranging from 19 to 88 years). From 104 patients, a total of 188 ultrasound examination results were registered. The patients included generally received their control examinations at the relevant department within one week and usually within a few days. The majority of the examinations were related to suspicion of gallstones (Figure 1). The rest of the scans were equally spread among the other four included examination types.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of sample selection for the study.

Overall, we found a Kappa value of 0.93 (95% CI: 0.87–0.98) between scans performed by GPs and the control examinations performed in the hospitals (Table 3). The Kappa values regarding ascites, abdominal aorta aneurism and intrauterine pregnancy were 1.

Table 3.

Study results

| Distribution of ultrasound scans |

Percentageagreement | Kappa value | 95% confidenceinterval | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All scans | Control scan |

Sensitivity | 0.98 | ||||||

| Yes | No | 96 | 0.93 | 0.8712–0.9796 | Specificity | 0.95 | |||

| GP scan | Yes | 87 | 5 | PPVb | 0.95 | ||||

| No | 2 | 94 | NPVc | 0.98 | |||||

| Gallstones | Control scan |

Sensitivity | 0.92 | ||||||

| Yes | No | 92 | 0.84 | 0.6969–0.9737 | Specificity | 0.92 | |||

| GP scan | Yes | 24 | 3 | PPVb | 0.89 | ||||

| No | 2 | 33 | NPVc | 0.94 | |||||

| Ascites | Control scan |

Sensitivity | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | No | 100 | 1 | 1.00–1.00 | Specificity | 1 | |||

| GP scan | Yes | 3 | 0 | PPVb | 1 | ||||

| No | 0 | 31 | NPVc | 1 | |||||

| Abdominal aorta >5 cm | Control scan |

Sensitivity | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | No | 100 | 1 | 1.00–1.00 | Specificity | 1 | |||

| GP scan | Yes | 1 | 0 | PPVb | 1 | ||||

| No | 0 | 28 | NPVc | 1 | |||||

| Intrauterine pregnancy | Control scan |

Sensitivity | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | No | 100 | 1 | 1.00–1.00 | Specificity | 1 | |||

| GP scan | Yes | 31 | 0 | PPVb | 1 | ||||

| No | 0 | 2 | NPVc | 1 | |||||

| Gestational age | Control scan |

Sensitivity | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | No | 93 | NAa | – | Specificity | 0d | |||

| GP scan | Yes | 28 | 2 | PPVb | 0.93 | ||||

| No | 0 | 0 | NPVc | NAe | |||||

A Kappa value could not be calculated because the actual data values were not binary for this parameter.

Positive predictive value.

Negative predictive value.

Value of zero because of the way data were registered for this specific parameter (Table 1).

NA because there were no negative test results because of the way these parameters were registered (Table 1).

Only two out of 30 scans for gestational age did not fall within the accepted three-day maximum difference. The maximum recorded difference was seven days. The average time used to perform the examinations by the GPs was just below six minutes per examination (ranging from two to fifteen minutes).

Discussion

Principal findings

Our study shows that point-of-care clinical ultrasound examinations with low-to-moderate complexity performed be GPs with sufficient prior training have a very high level of inter-rater agreement when compared to examinations conducted by radiologists and gynecologists.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to specifically investigate the quality of ultrasound examinations performed by GPs in a general practice setting. Our study investigated inter-rater agreement and not test results against a predefined Gold standard relevant for the different diagnoses. Therefore, the study cannot be interpreted as a marker for diagnostic accuracy toward the different clinical diagnoses. It is well known that an operator-dependent diagnostic procedure, such as an ultrasound examination, has a built-in inter-rater variation, even within expert groups of operators [15]. A limitation to the data analysis is present as the gestational age parameter is not applicable with Kappa statistic calculations because the actual value registered in our study was not binary. We did not include an interim analysis of examinations during the study period. Therefore, it is not possible to detect improvements in ultrasound skills, as a result of increasing experience. Furthermore, our participating GPs all completed the same ultrasound course prior to the study period. Hence, from our data collection, it is not possible to evaluate if an equally high inter-rater agreement could be achieved with less training. During the initial planning of the study protocol, there were some concerns regarding the time interval between examinations performed in general practice and the control scans. We tried to minimize the interval by motivating the participating patients to accept a booking for a control scan within a few days of their visit to general practice. Looking at the data collected, we showed a very high inter-rater agreement and we therefore do not expect that a shorter interval between scans would have resulted in significant changes in the observed results.

Findings in relation to other studies

Searching available relevant literature, it was not possible to find studies that were directly comparable with our study design. However, a few studies have focused on ultrasound examinations performed out of hospital setting by physicians with a background in general practice. Suramo et al. [16] investigated whether GPs could perform acceptable ultrasound examinations of the abdomen after an intensive training period. The examinations were supervised by a radiologist and performed in a hospital setting. Regarding ascites, abdominal aortic aneurism and gallstones, they found that the consistency between the examinations performed by the GPs and the radiologist was almost 100%. These results are very consistent with the findings in our study. Esquerra et al. [17] carried out a study where a group of GPs received education in performing abdominal ultrasound examinations in a hospital setting. In this setting, they selected simple abdominal ultrasound examinations to be performed by the GPs and thereafter by a radiologist. They used Kappa index to evaluate the consistency of results between the GPs and the radiologist. They found an overall Kappa index of 0.89 for all the abdominal organs. These findings relate very well to the Kappa index values found in our study. From the study of Esquerra et al., it is found that examinations of the spleen and pancreas had low Kappa index values (0.48 and 0.38). This might reflect that these organs are more difficult to obtain ultrasound images from and that they require more practice to interpret. Examination of these organs were not included in our study, but Esquerra et al.’s findings support our conclusion about low-to-moderate complex ultrasound examinations being the most suitable for general practice. Keith et al. [18] did a retrospective study on the accuracy of determined gestational age by using ultrasound examinations performed by GPs and radiologists. The examinations were performed by family practice residents and supervised by faculty mentors with training within obstetric ultrasound. They found a mean difference of 1.5 days between gestational age estimates performed by supervised residents and radiologists. Although our study did not register the exact difference in days but only regarding the accepted cutoff value of a three-day difference, we believe that we have a similar mean difference because 28 out of 30 scans (93%) fell within the three-day difference, and the maximum recorded difference was seven days.

Implications for clinicians and future research

We conclude that the use of ultrasound examinations in general practice has great potential.

It is fair to assume that with increasing complexity of ultrasound examinations comes a decreasing level of inter-rater agreement and reliability. We therefore suggest choosing low-to-moderately complex examinations to be performed in general practice. Preferably, these should be examinations with documented high inter-rater reliability and with a potential high supportive level in diagnostic or treatment decision making.

Further studies are needed to evaluate the level of training required to obtain and sustain sufficient skill level. Cost-benefit levels of performing ultrasound examinations in general practice may differ between countries because of geography, infrastructure, national healthcare systems and availability of hospital services and the cost of these [3].

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following participating GPs for their contributions: Michael Bukholt, Lukasz Damian Kamionka and Henrik Laustrup for data collection and study feedback. We also thank Mie Dilling Kjaer, MD, PhD, for his assistance with statistical calculations and Martin Bach Jensen, MD, Ph.D. for his constructive feedback on the article.

Funding Statement

The study received funding from the Regional Committee of Quality and Education in General Practice for Southern Denmark.

Disclosure statement

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes on contributors

Karsten Lindgaard, MD, is a Family medicine specialist. General Practice.

Lars Riisgaard, MD, is a Family medicine specialist. General Practice.

References

- 1.Bitsch M, Jensen F.. Klinisk Ultralyd Skanning [Clinical ultrasound scanning]. 1st ed Copenhagen: FADL´S Forlag; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore CL, Copel JA.. Point-of-care ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:749–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mengel-Jørgensen T, Jensen MB.. Variation in the use of point-of-care ultrasound in general practice in various European countries. Results of a survey among experts. Eur J Gen Pract. 2016;22:274–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bratland SZ. Ultralyddiagnostikk i almenpraksis [Ultrasonic diagnosis in general practice. An evaluation study]. Tidsskr nor Laegeforen. 1985;105:1939–1940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bratland SZ. Ultralydundersøkelse av nesens bihuler i almenpraksis [Ultrasonography of the paranasal sinuses in general practice]. Tidskr nor Laegeforen. 1985;105:1951–1953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bratland SZ. Ultralydundersøkelse av galleblaere i almenpraksis [Ultrasonography of the gallbladder in general practice]. Tidsskr nor Laegeforen. 1985;105:1946–1948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bratland SZ. Ultralydundersøkelse av gravide i almenpraksis [Ultrasonic diagnosis of pregnant women in general practice]. Tidsskr nor Laegeforen. 1985;105:1940–1946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bratland SZ. Ultralydundersøkelse av urinveier i almenpraksis [Ultrasonography of the urinary tract in general practice]. Tidskr nor Laegeforen. 1985;105:1948–1950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bratland SZ. Ultralyddiagnostikk anvendt i almenpraksis [Ultrasonic diagnosis used in general practice. A summarized evaluation]. Tidskr nor Laegeforen. 1985;105:1954–1955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wordsworth S, Scott A.. Ultrasound scanning by general practitioners: is it worthwhile? J Public Health Med. 2002;24:88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glasø M, Mediås IB, Straand J.. Diagnostisk ultralyd i en fastlegepraksis [Diagnostic ultrasound in general practice]. Tidsskr nor Laegeforen Nr. 15 2007;127:1924–1927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Center of Clinical Ultrasound (CECLUS), University of Aarhus. [Internet]. 2017 Available from: http://cesu.au.dk/fileadmin/www.medu.au.dk/uddannelse/projekt/CECLUS_Uddannelsesbeskrivelse_-_Ultralyd_i_almen_praksis_2015.pdf.

- 13.Kottner J, Audige L, Brorson S, et al. Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS) were proposed. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48:661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22:276–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naredo E, Möller I, Moragues C, et al. Interobserver reliability in musculoskeletal ultrasonography: results from a “Teach the Teachers” rheumatologist course. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;65:14–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suramo I, Merikanto J, Päivänsalo M, et al. General practitioner's skills to perform limited goal-oriented abdominal US examinations after one month of intensive training. Eur J Ultrasound. 2002;15:133–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Esquerrà M, Roura Poch P, Masat Ticó T, et al. Abdominal ultrasound: a diagnostic tool within the reach of general practitioners. Aten Primaria. 2012;44:576–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keith R, Frisch L.. Fetal biometry: a comparison of family physicians and radiologists. Fam Med. 2001;33:111–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]