Abstract

Background:

Given the strong influence of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors on musculoskeletal symptoms and limitations it’s important that both scientific and lay writing use the most positive, hopeful, and adaptive words and concepts consistent with medical evidence. The use of words that might reinforce misconceptions about preference-sensitive conditions (particularly those associated with age) could increase symptoms and limitations and might also distract patients from the treatment preferences they would select when informed and at ease.

Methods:

We reviewed 100 consecutive papers published in 2014 and 2015 in 6 orthopedic surgery scientific journals. We counted the number and proportion of journal articles with questionable use of one or more of the following words: tear, aggressive, required, and fail. For each word, we counted the rate of misuse per journal and the number of specific terms misused per article per journal

Results:

Eighty percent of all orthopedic scientific articles reviewed had questionable use of at least one term. Tear was most questionably used with respect to rotator cuff pathology. The words fail and require were the most common questionably used terms overall.

Conclusion:

The use of questionable words and concepts is common in scientific writing in orthopedic surgery. It’s worth considering whether traditional ways or referring to musculoskeletal illness merit rephrasing.

Keywords: Orthopedic surgery, Terminology, Word use

Introduction

Medical terms are a product of tradition, habit, experience, personal views, and professional background (1). Given the strong influence of thoughts, emotions, and behaviors on symptom intensity and magnitude of disability, it’s important that we use the most positive, hopeful, and adaptive terms and concepts in both scientific and lay writing. Patient reported outcomes are affected by attention, bedside manner, empathy, positive regard, compassion, hope, and enthusiasm (2-4). The terminology used by health care providers can alter what patients think and feel about their illness and their treatment options (2).

Patients seeking information about their illness from published material may encounter the use of questionable terms in both scientific and lay medical writing. Medical professionals often use jargon, may have less effective communication skills, and may themselves have misconceptions about specific types of illness and pathophysiology (1). An example in orthopedic surgery and musculoskeletal radiology might include use of the word “tear” to refer to all signal changes, thinning, and defect, thereby inappropriately implying that they are all traumatic when the evidence is that most are age-related (5-7).

The term “cognitive care” refers to the influence physicians have on patients’ beliefs about illness and treatment options. A patient’s views about a given treatment option can be made more positive, more negative, or more balanced depending upon the language used by the health care provider. For instance, terminology such as “good,” “safe,” and “effective” can create positive expectations surrounding treatment while “unsafe,” “ineffective,” “limited” and “potential side-effects” can make a treatment less appealing (2). For example, use of the word “aggressive” to describe certain stretching exercises might make them less appealing.

A review of studies of emotional and cognitive care found that healthcare professionals that reassured their patients and used a warm and inviting attitude achieved better health outcomes (2). Studies of health literacy in British patients with arthritis found that the term “self-management” triggered a negative emotional response (8). A study of companions of 100 patients presenting to a hand clinic identified that terms such as “pain” had a more negative emotional impact than the alternatives “discomfort” and “ache”(4). When an orthopedic surgeon uses the word “fail” to describe dissatisfaction with nonoperative treatment, he or she might be inadvertently reinforcing maladaptive cognitions and coping strategies and pushing the patient towards treatment with greater risks, discomforts, and inconveniences than they would otherwise prefer (4, 9).

Doctor-patient relationships are evolving from a paternalistic model to a shared decision making model in which patients share responsibility for their health care decisions. As patients become more involved in the decision making process the physician’s role is to provide them with all of the treatment options for their illness, including supportive treatment alone (10). The term “require” is often misapplied by orthopedic surgeons when describing surgery in patients that have other options.

We reviewed 100 articles from 6 orthopedic journals and counted the number and proportion of journal articles with questionable use of one or more of the following words: tear, aggressive, fail, and require. For each word, we also counted the rate of misuse per journal and the number of specific terms misused per article per journal.

Materials and Methods

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was not applicable. We analyzed use of the words failure, aggressive, require, and tear in 100 consecutive clinical research papers published in 2014 and 2015 in The Journal of Hand Surgery (Am) (JHS), Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma (JOT), Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research (CORR), Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Am) (JBJS), Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery (JSES), and Hand. Two research assistants assessed the word use as appropriate or questionable. Prior to selection each article was screened by a research assistant as biomechanical and basic science articles were not included in this study.

The use of fail- (i.e. “fail, failed, failure”) was classified as questionable in any circumstance that describes a therapy or treatment used for a patient. Was only considered appropriate when describing mechanical or equipment breakage.

In scientific writing the use of aggressive was never considered appropriate.

Use of the word requir- (i.e. “require, requiring”) was considered questionable when there were other options available. In any instance when require was used explaining IRB approval or exclusion criteria it was considered appropriate.

The word tear was considered questionable when it was used to describe a degenerative disease (tendinopathy) rather than an injury. For example, in the setting of acute trauma such as an elbow dislocation the use of tear was considered appropriate.

We counted the number and proportion of journal articles with questionable use of one or more words. Journals with 1 or more questionable terms were classified as an article with misuse. For each word, we counted the rate of misuse per journal and the number of specific terms misused per article per journal.

Results

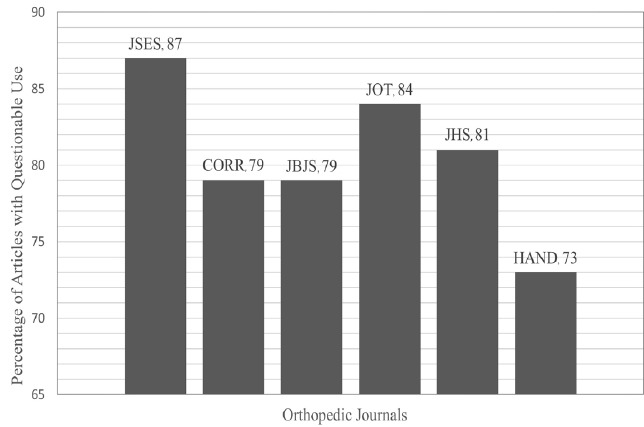

Eighty percent of all the orthopedic scientific articles reviewed had questionable use of at least one term [Figure 1]. Tear was most questionably used with respect to rotator cuff pathology [Table 1]. The words fail and require were the most common questionably used terms [Tables 1; 2].

Figure 1.

Percent of articles with at least one questionable term per journal.

Table 1.

Percent of articles with at least one questionable term by specific word *

| Fail | Aggressive | Require | Tear | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthopaedic Journals | 48 (9.7) | 11 (3.0) | 64 (6.2) | 13 (14) |

| Scientific Journal | ||||

| JSES | 65 | 7 | 67 | 42 |

| CORR | 50 | 15 | 63 | 5 |

| JBJS | 50 | 13 | 59 | 14 |

| JOT | 45 | 11 | 75 | 5 |

| JHS | 40 | 12 | 63 | 7 |

| HAND | 38 | 8 | 58 | 6 |

n=600

Discussion

There is evidence that common orthopedic language may have a negative emotive content that risks reinforcing illness (4, 9). Our study examined the questionable use of specific terminology in orthopedic scientific writing in six different peer review journals. The study examined the percent of orthopedic scientific articles that used questionable terminology, the rate of specific term misuse and the average number of questionably used terms.

The data from this study should be interpreted along with its limitations. The definition of questionable word use is based on an interpretation of best available evidence and a motivation to avoid reinforcing catastrophic thinking a definition that some might not share. The determination of questionable word use was somewhat subjective, but there were few instances of debate.

Eighty percent of all orthopedic scientific articles reviewed had questionable use of at least one term. Authors and investigators have also noted the use of questionable terms in obstetrics, cardiology, surgery, and biomechanical research. Inconsistent or questionable terms in medical writing are ascribed to misunderstanding of the definition of the word, lack of a consensus definition, and underappreciation of the emotive content of the terms (1, 4, 11).

The term tear was most questionably applied to rotator cuff tendinopathy. We have gotten into the habit of referring to all degrees of degenerative tendinopathy and signal changes on magnetic resonance imaging as a tear (e.g. “partial tear” for signal change or arthroscopically visualized attrition). The word “tear” implies damage in need of repair. Best evidence suggests that tendinopathy of the rotator cuff is an expected part of the human aging process (5-7). In other words, the word tear may not be any more appropriate for a defect in the rotator cuff than it is for a defect in one’s hair (a bald spot). The evidence that asymptomatic shoulders have similar pathology to symptomatic shoulders supports an analogy with greying and thinning of the hair, which is an atraumatic process as is presbyopia (12). The use of more adaptive terms to describe rotator cuff defects might lead to improved health with diminished use of resources by encouraging more adaptive and less passive coping strategies while limiting the stress and distress that accompanies the sense that one might lose the ability to depend on one’s body.

We found that the terms “require” and “fail” were the most questionably used terms in orthopedic scientific writing. These terms imply limited options and pass negative judgment respectively, where such emotive content is not warranted (4, 9). In most instances when the word “require” is used to refer to a management option, the patient and surgeon have actually chosen from among several options. For instance, reoperation is rarely “required” unless perhaps there is a problem such as a severe infection. And patients don’t “fail” a treatment-they are not satisfied with a given treatment. No one wants to fail and patients need to understand that they are trying to find the best way to depend on their bodies during illness. It’s not about finding the correct or curative treatment, it’s about being able to be one’s self in spite of symptoms or impairments, many of which cannot currently be cured by modern medicine.

This study identified questionable use of medical terminology amongst orthopedic surgeons in scientific writing. Additional research is merited to measure the impact of negative or questionable terms in orthopedic surgery, and the benefit of using alternative more positive, optimistic, and hopeful terms.

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

Table 2.

Average number of questionable use per article per journal for specific terms *

| Overall Misuse | Fail | Aggressive | Require | Tear | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthopaedic Journals | 9 (4.8) | 3 (1.4) | 0.23 (0.11) | 3 (0.66) | 3 (3.8) |

| Scientific Journal | |||||

| JSES | 18 | 4.9 | 0.080 | 3.1 | 9.8 |

| CORR | 7.6 | 4.5 | 0.30 | 2.2 | 0.52 |

| JBJS | 11 | 3.6 | 0.39 | 2.8 | 4.1 |

| JOT | 6.9 | 2.5 | 0.20 | 4.2 | 0.071 |

| JHS | 5.2 | 1.9 | 0.21 | 2.8 | 0.23 |

| HAND | 5.3 | 1.6 | 0.16 | 2.8 | 0.80 |

n=600

References

- 1.Barker KL, Reid M, Minns Lowe CJ. Divided by a lack of common language? A qualitative study exploring the use of language by health professionals treating back pain. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2009;10(1):e123. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-10-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Blasi Z, Harkness E, Ernst E, Georgiou A, Kleijnen J. Influence of context effects on health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet. 2001;357(9258):757–62. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)04169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verheul W, Sanders A, Bensing J. The effects of physicians’ affect-oriented communication style and raising expectations on analogue patients’ anxiety, affect and expectancies. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(3):300–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vranceanu AM, Elbon M, Adams M, Ring D. The emotive impact of medical language. Hand (N Y) 2012;7(3):293–6. doi: 10.1007/s11552-012-9419-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamaguchi K, Ditsios K, Middleton WD, Hildebolt CF, Galatz LM, Teefey SA. The demographic and morphological features of rotator cuff disease. A comparison of asymptomatic and symptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1699–704. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamamoto A, Takagishi K, Osawa T, Yanagawa T, Nakajima D, Shitara H, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(1):116–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sher JS, Uribe JW, Posada A, Murphy BJ, Zlatkin MB. Abnormal findings on magnetic resonance images of asymptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(1):10–5. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barker KL, Reid M, Minns Lowe CJ. What does the language we use about arthritis mean to people who have osteoarthritis? A qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(5):367–72. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.793409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vranceanu AM, Elbon M, Ring D. The emotive impact of orthopedic words. J Hand Ther. 2011;24(2):112–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jht.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brom L, Pasman HR, Widdershoven GA, van der Vorst MJ, Reijneveld JC, Postma TJ, et al. Patients’ preferences for participation in treatment decision-making at the end of life: qualitative interviews with advanced cancer patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e100435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berghella V, Blackwell SC, Ramin SM, Sibai BM, Saade GR. Use and misuse of the term “elective” in obstetrics. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 Pt 1):372–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820780ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mall NA, Kim HM, Keener JD, Steger-May K, Teefey SA, Middleton WD, et al. Symptomatic progression of asymptomatic rotator cuff tears: a prospective study of clinical and sonographic variables. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(16):2623–33. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]