Abstract

The Hippo pathway is an evolutionarily conserved signaling pathway that plays important roles in stem cell biology, tissue homeostasis, and cancer development. Vestigial-like 4 (Vgll4) functions as a transcriptional co-repressor in the Hippo-Yes-associated protein (YAP) pathway. Vgll4 inhibits cell proliferation and tumor growth by competing with YAP for binding to TEA-domain proteins (TEADs). However, the mechanisms by which Vgll4 itself is regulated are unclear. Here we identified a mechanism that regulates Vgll4's tumor-suppressing function. We found that Vgll4 is phosphorylated in vitro and in vivo by cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) during antimitotic drug-induced mitotic arrest and also in normal mitosis. We further identified Ser-58, Ser-155, Thr-159, and Ser-280 as the main mitotic phosphorylation sites in Vgll4. We also noted that the nonphosphorylatable mutant Vgll4-4A (S58A/S155A/T159A/S280A) suppressed tumorigenesis in pancreatic cancer cells in vitro and in vivo to a greater extent than did wild-type Vgll4, suggesting that mitotic phosphorylation inhibits Vgll4's tumor-suppressive activity. Consistent with these observations, the Vgll4-4A mutant possessed higher-binding affinity to TEAD1 than wild-type Vgll4. Interestingly, Vgll4 and Vgll4-4A markedly suppressed YAP and β-catenin signaling activity. Together, these findings reveal a previously unrecognized mechanism for Vgll4 regulation in mitosis and its role in tumorigenesis.

Keywords: cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK), Hippo pathway, mitosis, phosphorylation, tumor suppressor gene

Introduction

The Hippo pathway is an evolutionarily conserved signaling pathway that controls organ size and tumorigenesis (1). The Hippo core signaling pathway features a kinase cascade consisting of mammalian sterile-20 like protein 1/2 (Mst1/2) and large tumor suppressor 1/2 (Lats1/2) (1–3). Inactivation of the Hippo pathway is correlated with promotion of proliferation and anti-apoptosis through activation of the transcriptional co-activator Yes-associated protein (YAP).4 YAP functions through binding with TEA-domain transcription factors (TEAD1–4) to activate target genes, including connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) (4). Hippo-YAP and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways have a shared core feature: the phosphorylation-dependent control of the key transcriptional co-activators, YAP and β-catenin, respectively (5). In addition to this similarity, recent studies showed multipoint cross-talk between the Hippo-YAP and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways (6).

Vestigial-like protein 4 (Vgll4) (Tgi in Drosophila) is a newly identified protein in the Hippo pathway and is an antagonist of Yki/YAP (7). Vgll4 functions as a transcriptional repressor by directly competing with YAP binding to TEADs (7). Several reports demonstrated that Vgll4 is a tumor suppressor in lung, gastric, and colorectal cancer by negatively regulating the YAP-TEAD transcriptional complex and TCF4-TEAD4 transactivation (5, 8–11). Furthermore, genetic screens in mice identified Vgll4 as a tumor suppressor candidate in pancreatic cancer, although its biological significance has not been examined (12).

Although extensive studies have demonstrated the fundamental roles for the Hippo-YAP pathway in tumorigenesis, exploration of the underlying mechanisms driving it are still incomplete. Interestingly, some of the Hippo-YAP core components have been associated with the mitotic machinery and are phospho-regulated during mitosis. Dysregulation of many of the Hippo-YAP pathway members and regulators causes mitotic defects, which are common characteristics of a tumor cell. Therefore, we speculate that Hippo-YAP signaling may exert its oncogenic or tumor suppressive function via dysregulation of mitosis. However, the regulation of Vgll4 in mitosis and its possible role in cancer have remained elusive. In this study we found that the mitotic kinase cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (CDK1) phosphorylates Vgll4 at Ser-58, Ser-155/Thr-159, and Ser-280 during mitosis. Moreover, the mitotic phosphorylation-deficient mutant (Vgll4-4A, harboring S58A/S155A/T159A/S280A) possesses much stronger tumor suppressive activity compared with wild-type Vgll4 in pancreatic cancer tumorigenesis in vitro and in vivo. Our findings reveal a novel layer of regulation for Vgll4 in mitosis and cancer development.

Results

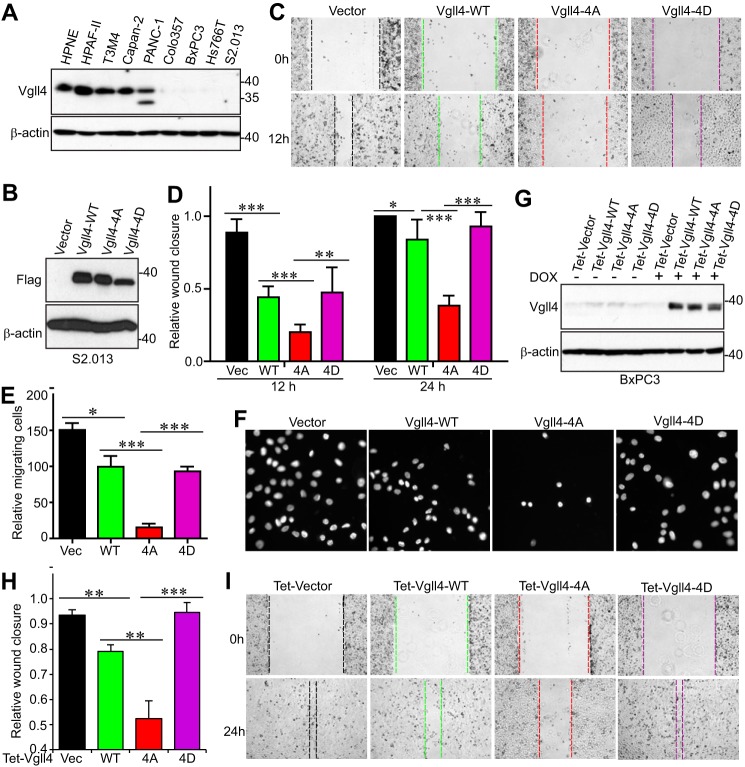

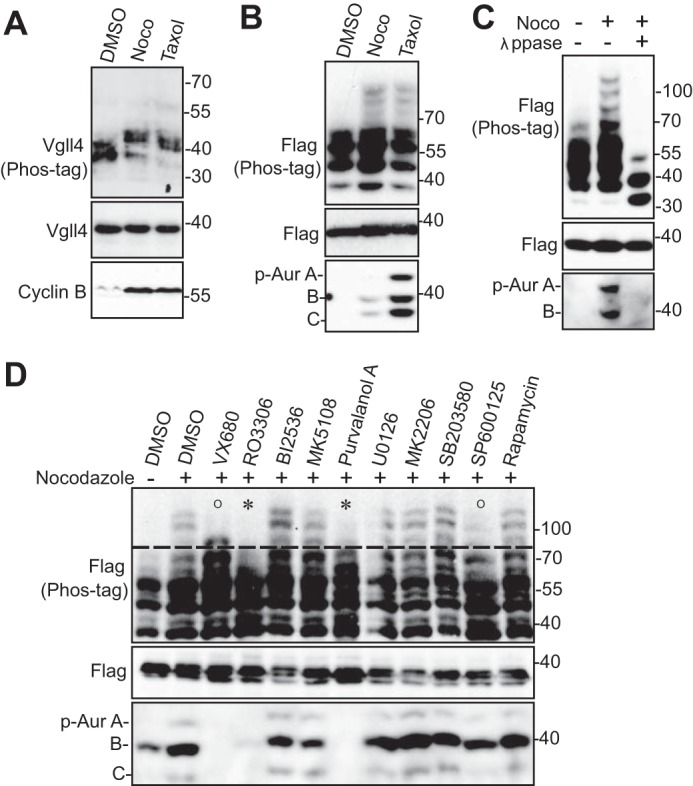

Vgll4 was phosphorylated during antimitotic drug-induced G2/M arrest

We recently showed that several regulators of the Hippo-YAP signaling are phosphorylated during mitosis (13–18). We further explored whether the newly identified transcriptional repressor Vgll4 in the Hippo-YAP pathway is regulated by phosphorylation during mitosis. As shown in Fig. 1A, Vgll4 protein was up-shifted on a Phos-tag gel during taxol or nocodazole-induced G2/M arrest (Fig. 1A). Transiently transfected Vgll4 mobility was also retarded during taxol or nocodazole treatment (Fig. 1B). λ-Phosphatase treatment largely converted all up-shifted bands to fast-migrating bands, confirming that the mobility shift of Vgll4 during G2/M arrest is caused by phosphorylation (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

CDK1-dependent phosphorylation of Vgll4 during G2/M arrest. A, HeLa cells were treated with DMSO, taxol (100 nm for 16 h), or nocodazole (Noco, 100 ng/ml for 16 h). Total cell lysates were probed with the indicated antibodies on Phos-tag or regular SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Increased cyclin B levels served as a mitotic marker. B, HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged Vgll4 and treated as indicated in A. Total cell lysates were used for Western blotting analysis as described in A. p-Aur, Phospho-Aurora. C, HEK293T were transfected and treated as in B. The transfected cell lysates were further treated with (+) or without (−) λ-phosphatase (λppase). D, HEK293T cells were transfected and treated with nocodazole together with or without various kinase inhibitors as indicated. VX680 (2 μm), MK5108 (10 μm), BI2536 (100 nm), RO3306 (5 μm), U0126 (20 μm), MK2206 (1 μm), SB203580 (10 μm), SP600125 (20 μm), rapamycin (100 nm), and purvalanol A (10 μm) were used. Inhibitors were added (with MG132 to prevent cyclin B from degradation and cells from exiting from mitosis) 2 h before harvesting the cells. Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. O and * mark the modest and significant inhibition of mobility upshift, respectively. Phospho-Aurora levels (in panels B–D) served as a mitotic marker and indicate the inhibitory effects mediated by kinase inhibitors (in panel D).

Kinase identification for Vgll4 phosphorylation

Next, we used various kinase inhibitors to identify the candidate kinase for Vgll4 phosphorylation. Inhibition of Aurora-A, -B, and -C (with VX680) or JNK1/2 (with SP600125) kinases mildly reduced Vgll4 phosphorylation (Fig. 1D). Inhibition of MEK-ERK kinases (with U0126), p38 (with SB203580), mTOR (with rapamycin), Akt (MK2206), Aurora-A (MK5108), or Plk1 (with BI2536) failed to alter the phosphorylation of Vgll4 during G2/M arrest (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, treatments with RO3306 (CDK1 inhibitor) or purvalanol A (CDK1/2/5 inhibitor) significantly inhibited the mobility shift/phosphorylation (Fig. 1D, fourth and seventh lanes). These data suggest that CDK1, which is a well known master mitotic kinase, is likely the relevant kinase for Vgll4 phosphorylation induced during taxol or nocodazole treatment.

CDK1 phosphorylated Vgll4 in vitro

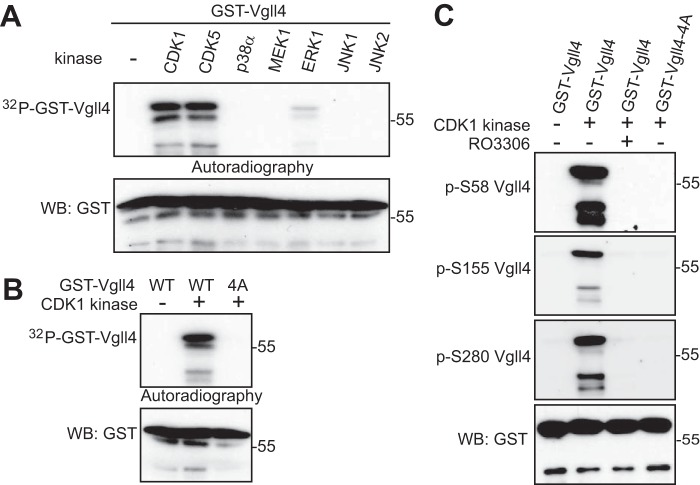

To determine whether CDK1 kinase can directly phosphorylate Vgll4, we performed in vitro kinase assays with GST-tagged Vgll4 proteins as substrates. Fig. 2A shows that purified CDK1–cyclin B kinase complex phosphorylated GST-Vgll4 proteins in vitro (Fig. 2A). We also included several other kinases that phosphorylate the same consensus sequence as CDK1 and found CDK5–p25 kinase complex was able to phosphorylate Vgll4 (Fig. 2A). These results indicate that CDK1 and -5 directly phosphorylate(s) Vgll4 in vitro.

Figure 2.

Vgll4 is phosphorylated by CDK1 in vitro. A, GST-tagged Vgll4 proteins were used for in vitro kinase assays with purified kinases. B, GST-tagged Vgll4 or Vgll4-4A (S58A/S155A/T159A/S280A) proteins were used for in vitro kinase assays with purified CDK1–cyclin B kinase complex. WB, Western blotting. C, in vitro kinase assays were done as in B except anti-phospho-Vgll4 antibodies were used. RO3306 (5 μm) was used to inhibit CDK1 kinase activity. The phospho-Vgll4 Ser-155/Thr-159 antibody was labeled as p-S155 Vgll4.

CDK1–cyclin B complex phosphorylated Vgll4 at multiple sites

CDK1 phosphorylates substrates at a minimal proline-directed consensus sequence (19). Human Vgll4 contains seven S/TP motifs (Ser-58, Ser-109, Ser-155, Thr-159, Ser-268, Ser-280, and Ser-291). Interestingly, mutating four of them to alanines (Vgll4-4A, S58A/S155A/T159A/S280A) completely abolished 32P incorporation on Vgll4 in an in vitro kinase assay, suggesting that these four sites are the main phosphorylation sites for CDK1 (Fig. 2B). Database analysis revealed that all four sites have been identified as mitotic phosphorylation sites by previous phospho-proteomic studies (20).

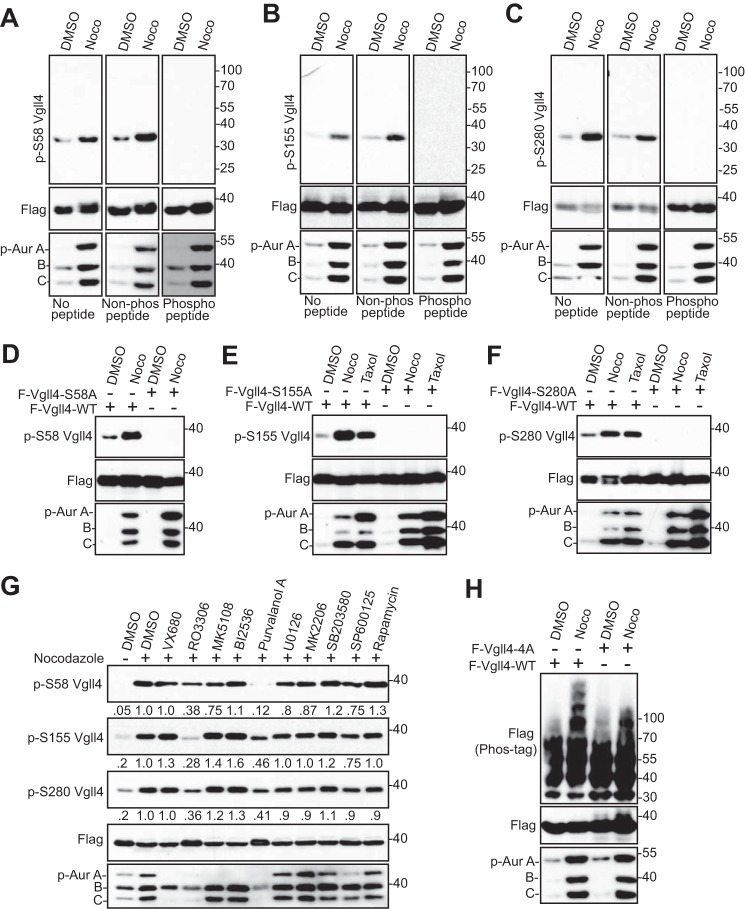

We have generated phospho-specific antibodies against Ser-58, Ser-155/Thr-159, and Ser-280. In vitro kinase assays confirmed that CDK1 robustly phosphorylates Vgll4 at all these sites (Fig. 2C). As expected, the addition of RO3306 or mutating the sites to alanines abolished the phosphorylation (Fig. 2C). These data suggest that CDK1 phosphorylates Vgll4 at Ser-58, Ser-155/Thr-159, and Ser-280 in vitro. Next, we explored whether mitotic phosphorylation of Vgll4 occurs in cells. Nocodazole treatment significantly increased the phosphorylation of Ser-58 on transfected Vgll4 (Fig. 3A). Phosphopeptide, but not the regular non-phosphopeptide, incubation completely blocked the phospho-signal, suggesting that this antibody detects the phosphorylated form of Vgll4 (Fig. 3A). Similar results were observed for phospho-antibodies against Ser-155/Thr-159 and Ser-280 (Fig. 3, B and C). The signal was abolished by mutating the relevant site to alanine (Fig. 3, D–F), confirming the specificity of these phospho-antibodies. Using kinase inhibitors, we further demonstrated that phosphorylation of Vgll4 is CDK1 kinase-dependent (Fig. 3G, fourth and seventh lanes). In line with the in vitro data (Fig. 2B), the mobility upshift of Vgll4 induced by nocodazole treatment was also largely inhibited when these sites were mutated to alanines (Fig. 3H). Taken together, these observations indicate that Vgll4 is phosphorylated at Ser-58, Ser-155/Thr-159, and Ser-280 by CDK1 in cells during antimitotic drug-induced G2/M arrest.

Figure 3.

Vgll4 is phosphorylated by CDK1 in cells. A–C, HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-Vgll4. At 32 h post-transfection the cells were treated with nocodazole (Noco) for 16 h. Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. No peptide, Western blotting without any peptide (regular Western blotting); Non-phospho peptide, Western blotting in the presence of control (not phosphorylated) peptide; phosphopeptide, Western blotting in the presence of corresponding phosphorylated peptide (used for antibody generation). See “Experimental Procedures.” p-Aur, Phospho-Aurora. D–F, HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-Vgll4 or FLAG-Vgll4 mutants as indicated. At 32 h post-transfection, the cells were treated with nocodazole or taxol for 16 h. Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. G, HEK293T cells were transfected and treated with nocodazole together with or without various kinase inhibitors as indicated. Inhibitors were added (with MG132 to prevent cyclin B from degradation and cells from exiting from mitosis) 1.5 h before harvesting the cells. Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. The phospho-Vgll4 Ser-155/Thr-159 antibody was labeled as p-S155 Vgll4. The relative phosphorylation levels are quantified from three blots by ImageJ. H, HEK293T cells were transfected with FLAG-Vgll4 or FLAG-Vgll4-4A and treated as indicated. Total cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Phospho-Aurora levels (in panels A–F and H) served as a mitotic marker and indicate the inhibitory effects mediated by kinase inhibitors (in panel G).

CDK1 mediated Vgll4 phosphorylation in mitotically arrested cells

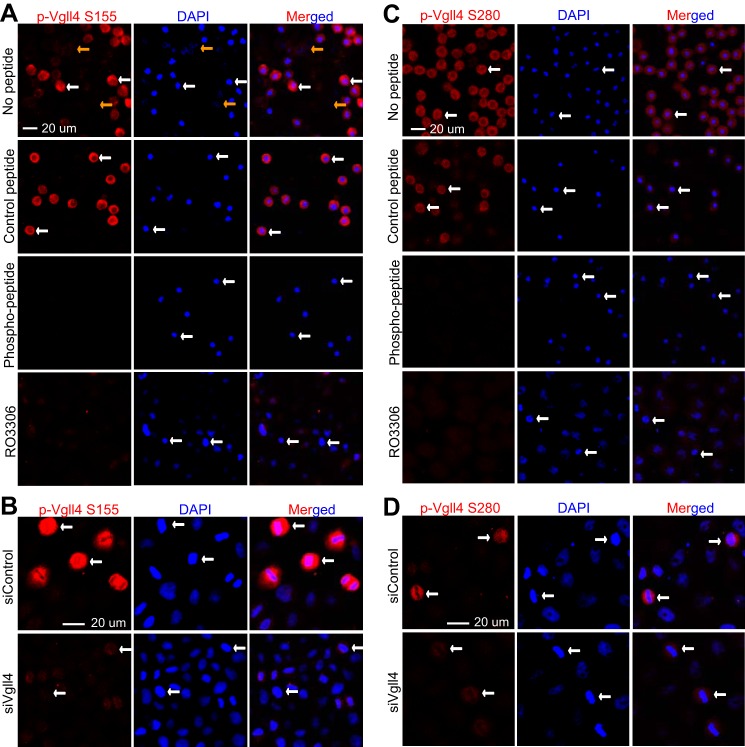

We next performed immunofluorescence microscopy with these phospho-specific antibodies to examine the phospho-status of endogenous Vgll4. The antibodies against Ser-155/Thr-159 detected strong signals in nocodazole-arrested prometaphase cells (Fig. 4A, white arrows). The signal was very low or not detectable in interphase cells (Fig. 4A, yellow arrows). Again, phosphopeptide, but not control non-phosphopeptide, incubation completely blocked the signal, suggesting that these antibodies specifically detect Vgll4 only when it is phosphorylated (Fig. 4A). The addition of RO3306 (CDK1 inhibitor) largely diminished the signals detected by p-Vgll4 Ser-155/Thr-159 antibodies in mitotically arrested cells, further indicating that the phosphorylation is CDK1-dependent (Fig. 4A, low panels). Moreover, siRNA-mediated knockdown of Vgll4 also significantly reduced the phospho-signal (Fig. 4B), confirming the specificity of the antibody. Similar results were observed when the phospho-Ser-280 antibody was used (Fig. 4, C and D).

Figure 4.

CDK1 phosphorylated Vgll4 during G2/M-phase arrest. A, HeLa cells were treated with nocodazole and then fixed. Before the cells were stained with phospho-specific antibody against Ser-155/Thr-159 of Vgll4 (p-Vgll4 S155), they were preincubated with PBS (no peptide control) or non-phosphorylated (control) peptide or the phosphorylated peptide used for immunizing rabbits. CDK1 inhibitors RO3306 (5 μm) together with MG132 (25 μm) were added 2 h before the cells were fixed. B, HeLa cells were transfected with scramble siRNA or siRNAs targeting Vgll4. At 48 h post-transfection, cells were treated with nocodazole and then fixed for staining with phospho-Vgll4 Ser-155/Thr-159 (p-Vgll4 S155) antibodies. C and D, experiments were done similarly as in A and B with phospho-specific antibody against Ser-280 of Vgll4. White and yellow arrows mark some of the prometaphase cells and the interphase cells, respectively.

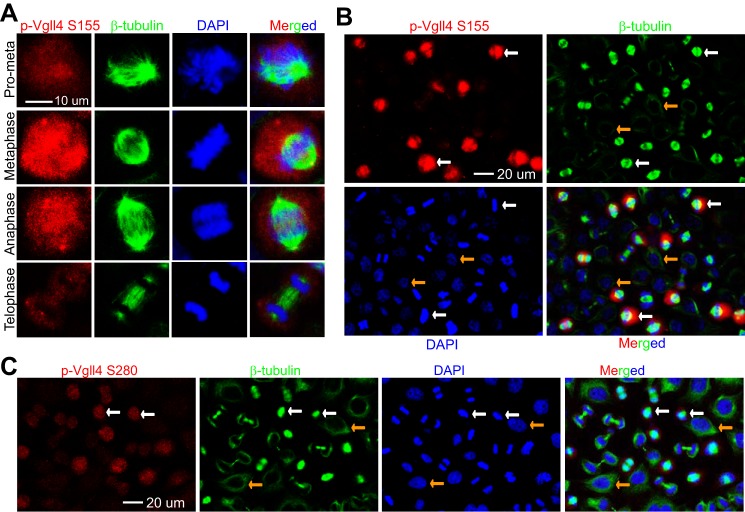

Vgll4 phosphorylation occurred during normal mitosis

Taxol or nocodazole was used to arrest cells in G2/M phase in all of the above experiments. We wanted to determine whether phosphorylation of Vgll4 occurs during normal mitosis. We performed immunofluorescence staining on cells collected from a double thymidine block and release (21). Consistent with the results in Fig. 4, very weak signals were detected in interphase or telophase/cytokinesis cells (Fig. 5, A–C). The phospho-signal increased in prometaphase and peaked in metaphase cells (Fig. 5, A–C). These results indicate that Vgll4 phosphorylation occurs dynamically during normal mitosis.

Figure 5.

Vgll4 is phosphorylated during unperturbed mitosis. A and B, HeLa cells were synchronized by a double thymidine block and release method. Cells were stained with antibodies against p-Vgll4 Ser-155/Thr-159 (labeled as p-Vgll4 S155) or β-tubulin or with DAPI. A low power (40× objective) lens was used to view various phases of the cells in a field (B). C, experiments were done similarly as in B with p-Vgll4 Ser-280 antibodies. White and yellow arrows (in panels B and C) mark the metaphase and interphase cells, respectively.

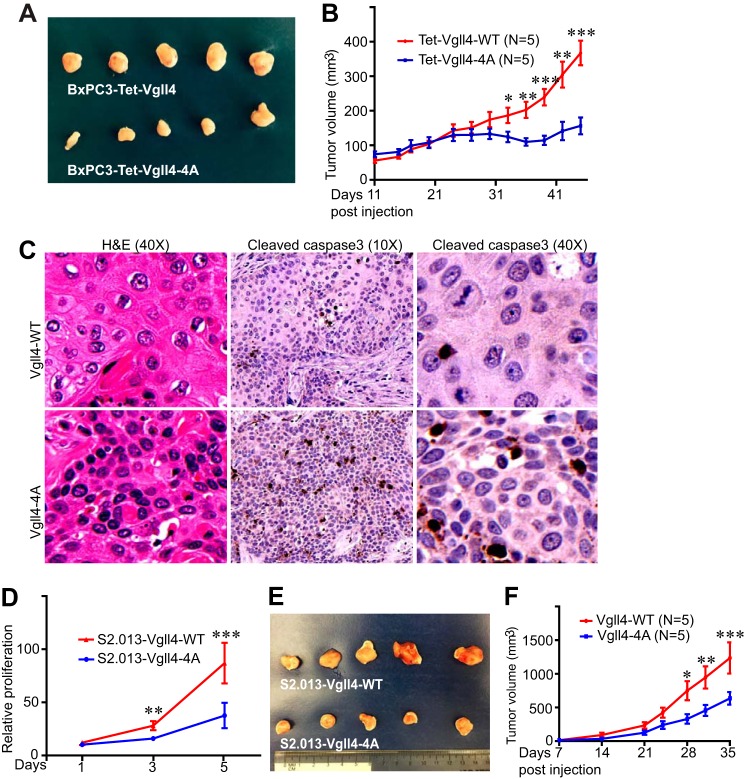

Mitotic phosphorylation of Vgll4 inhibited its tumor-suppressing activity in vitro

Vgll4 suppresses tumor growth in colorectal, lung, and gastric cancer cells and functions as a potential tumor suppressor in pancreatic cancer as well (5, 8–12). Next, we utilized pancreatic cancer cell lines as a model system to determine the biological significance of mitotic phosphorylation of Vgll4. First, we examined Vgll4 protein levels in HPNE (an immortalized pancreatic epithelial cell line) and various pancreatic cancer cell lines. Vgll4 expression was very low or not detectable in half of the cancer cell lines and was high in HPNE cells (Fig. 6A). We stably re-expressed wild-type Vgll4 or Vgll4-4A (non-phosphorylatable mutant) or Vgll4-4D (phospho-mimetic mutant) in S2.013 (Fig. 6B). Not surprisingly, ectopic expression of wild-type Vgll4 suppressed migration and proliferation in S2.013 cells (Fig. 6, C–F, and data not shown). Interestingly, cells expressing Vgll4-4A showed greater inhibition in migration (Fig. 6, C–F). In contrast, Vgll4-4D-expressing cells migrated similarly to Vgll4-expressing or vector-expressing cells (Fig. 6, C–F). Using a doxycycline-inducible system (Fig. 6G), we further showed that BxPC3 cells expressing Vgll4-4A possess stronger inhibitory activity in migration when compared with wild-type Vgll4-expressing cells (Fig. 6, H–I). Without doxycycline induction, these BxPC3 cell lines express similar levels of Vgll4 proteins (Fig. 6G, left four lanes), and no migration and proliferation differences were detected among these cells (data not shown). These findings suggest that mitotic phosphorylation of Vgll4 inhibits its tumor-suppressive function.

Figure 6.

Mitotic phosphorylation of Vgll4 inhibited its tumor-suppressing activity in pancreatic cancer cells. A, Vgll4 expression in pancreatic non-cancer (HPNE) and cancer cells. B, establishment of S2.013 cell lines stably expressing vector (Vec), wild-type Vgll4, Vgll4-4A, or Vgll4-4D (all are FLAG-tagged). 4A, S58A/S155A/T159A/S280A; 4D, S58D/S155D/T159D/S280D. C and D, cell migration (wound healing) assays with cell lines established in B. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05 (t test). E and F, cell migration (Transwell) assays with cell lines established in B. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. ***, p < 0.001; *, p < 0.05 (t test). G, establishment of Tet-On-inducible cell lines expressing wild-type Vgll4 or Vgll4-4A or Vgll4-4D in BxPC3 pancreatic cancer cells. Cells were kept on Tet-approved FBS, and doxycycline was added (1 μg/ml) to the cells 2 days before the experiments. H and I, cell migration (wound healing) assays with cell lines established in G. Data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01 (t test).

Mitotic phosphorylation of Vgll4 inhibits its tumor-suppressing activity in vivo

We next evaluated the influence of mitotic phosphorylation of Vgll4 on tumor growth in animals. BxPC3 cells expressing wild-type Vgll4 or Vgll4-4A were subcutaneously inoculated into immuno-deficient mice. Interestingly, tumors from mice harboring Vgll4-4A-expressing cells were significantly smaller when compared with those from mice injected with wild-type Vgll4-expressing cells (Fig. 7, A and B). Histopathological examination revealed that tumor cells expressing Vgll4-4A were smaller and in higher density when compared with wild-type Vgll4 tumor cells (Fig. 7C and data not shown). Immunohistochemistry staining with cleaved caspase-3 (an apoptosis marker) showed that expression of Vgll4-4A significantly promoted tumor cell death (Fig. 7C). Similarly, we found that S2.013 cells expressing Vgll4-4A proliferate at a significantly lower rate and form smaller tumors than cells expressing Vgll4-WT (Fig. 7, D–F). These results support the hypothesis that mitotic phosphorylation inhibits Vgll4's tumor suppressive activity in vivo.

Figure 7.

Non-phosphorylated Vgll4 suppressed tumorigenesis in mice. A, representative five tumors in each group were excised and photographed at the end point. B, tumor growth curve with BxPC3 cells. BxPC3 cells expressing wild-type Vgll4 or Vgll4-4A (Tet-On-inducible) were subcutaneously inoculated into athymic nude mice on both flanks, and the mice were kept on doxycycline (0.5 mg/ml) in their drinking water throughout the experiment. The tumor volume shown at each point was the average from 8 tumors (two injections on two mice in each group did not form visible tumors and were excluded from the analysis). ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05 (t test). C, hematoxylin and eosin and cleaved caspase-3 staining in tumors shown in A. Three tumors from each group were analyzed. D, cell proliferation curve with S2.103 cells expressing Vgll4-WT or Vgll4-4A. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01(t test). E and F, similar experiments were done as in (A and B) with S2.013 cell lines. ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05 (t test).

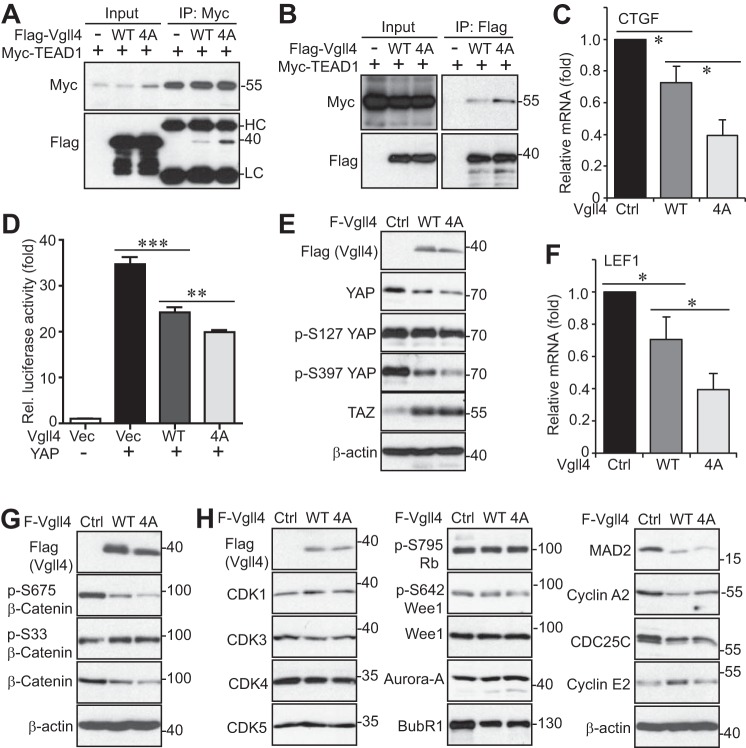

Mitotic phosphorylation of Vgll4 affected YAP and β-catenin activity

Vgll4 competes with YAP to associate with TEADs (7). The association between Vgll4 and TEAD1 was confirmed with transfected proteins (Fig. 8, A and B). Interestingly, the non-phosphorylatable (Vgll4-4A) mutant had greater binding affinity with TEAD1 compared with wild-type Vgll4 (Fig. 8, A and B), suggesting that Vgll4 phosphorylation inhibits its association with TEAD1. These observations are consistent with our results from functional assays shown in Figs. 6 and 7 and support the notion that Vgll4-4A suppresses tumor growth by regulating TEAD1 transcriptional activity. Indeed, the mRNA level for CTGF (a well known YAP-TEAD target) was significantly reduced in Vgll4-4A-expressing cells (Fig. 8C). TEAD-luciferase reporter assays further confirmed that Vgll4-4A has higher suppressing activity than wild-type Vgll4 (Fig. 8D). Interestingly, total YAP protein levels, as well as YAP phosphorylation at Ser-127 and Ser-397, were significantly reduced in Vgll4- or to a greater extent in Vgll4-4A-expressing cells (Fig. 8E). In addition to repressing the YAP-TEAD activity, a recent report showed that Vgll4 also suppresses the TCF4-TEAD transcription complex in the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (5). In line with this previous study, the expression of β-catenin/TCF4 target LEF1 was significantly inhibited by Vgll4 or Vgll4-4A expression in S2.013 cells (Fig. 8F). Vgll4 expression also decreased the levels of the β-catenin protein and the activating phosphorylation at Ser-675, probably through increasing the inhibitory phosphorylation at Ser-33/Ser-37/Thr-41 (Fig. 8G). Again, expression of the Vgll4-4A mutant tended to have stronger inhibitory activity compared with wild-type Vgll4 (Fig. 8, F and G). These results suggest that mitotic phosphorylation of Vgll4 affects both YAP and β-catenin activity in pancreatic cancer cells.

Figure 8.

Mitotic phosphorylation of Vgll4 affected YAP and β-catenin activity and regulated the expression of cell cycle regulators. A and B, HEK293T cells were transfected with various DNA plasmids as indicated. The immunoprecipitates (IP, with FLAG or Myc antibodies) were probed with the indicated antibodies. Total cell lysates before immunoprecipitation were also included (input). C, quantitative RT-PCR for CTGF in S2.013 cell lines expressing vector, wild-type Vgll4, or Vgll4-4A. *, p < 0.05 (t test). D, luciferase reporter assays in HEK293T cells. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001 (t test). E, total cell lysates from S2.013 cell lines expressing vector, wild-type Vgll4, or Vgll4-4A were probed with the indicated antibodies (YAP-related). F, quantitative RT-PCR for LEF1 in S2.013 cell lines expressing vector, wild-type Vgll4, or Vgll4-4A. *, p < 0.05 (t test). G, total cell lysates from S2.013 cell lines expressing vector, wild-type Vgll4, or Vgll4-4A were probed with the indicated antibodies (β-catenin-related). H, total cell lysates were harvested from S2.013 cell lines expressing vector, wild-type Vgll4, or Vgll4-4A and were subjected to Western-blotting analysis with various cell cycle regulators.

We further determined whether Vgll4 and its mitotic phosphorylation affects cell cycle regulators. Interestingly, the levels of budding uninhibited by benzimidazole 1-related protein kinase (BubR1), mitotic arrest deficiency 2 (MAD2), cyclin A2, and CDC25C declined upon Vgll4/Vgll4-4A expression in S2.013 cells (Fig. 8H). However, both Vgll4 and Vgll4-4A decreased these proteins to similar levels (Fig. 8H), suggesting that these regulators are unlikely involved in mediating the effects of Vgll4-4A in suppressing tumor growth.

Discussion

Dysregulation of the Hippo-YAP signaling pathway has been associated with the development of various cancers. Oncoprotein YAP functions together with transcriptional factors TEAD1–4 to regulate downstream target gene expression (4). Like YAP, Vgll4 does not contain a DNA-binding domain, and it functions as a transcriptional repressor via Tondu domains binding with TEADs (7). Therefore, Vgll4 suppresses cell growth by directly competing with YAP via binding with TEADs. The Tondu region of Vgll4 is sufficient for inhibiting YAP activity, and a peptide mimicking Vgll4 could function as a YAP antagonist and potently inhibit gastric and colorectal tumor growth (5, 8). Low expression of Vgll4 is correlated with poor prognosis and survival in several cancers (5, 8, 9, 12). However, although its tumor suppressive activity has been well documented, little attention has been directed at the possible regulation for Vgll4 in cancer development. This study identified novel mitotic phosphorylation of Vgll4 and demonstrated that this mitotic phosphorylation controls Vgll4's tumor suppressing activity. Compared with wild-type Vgll4, the phospho-deficient Vgll4-4A mutant has a higher affinity pairing with TEAD1 and shows stronger tumor suppressive activity. These observations suggest that in addition to its expression levels, the phosphorylation status of Vgll4 is also critical for its tumor suppressive function. Thus, our study revealed another layer of regulation for Vgll4 activity during tumorigenesis.

In the current study we found that CDK1 phosphorylates Vgll4 in vitro and in vivo at Ser-58, Ser-155/Thr-159, and Ser-280 during mitosis (Figs. 2–5). Recently, we reported that CDK1-mediated phosphorylation of YAP promotes mitotic defects, including centrosome amplification and chromosome missegregation, and potentiates oncogenic functions of YAP (16, 22). Considering that CDK1 phosphorylates both YAP and Vgll4 during mitosis and these proteins function together in regulating tumorigenesis, one question is whether these phosphorylation events affect each other during mitosis. Mechanistic elucidation of this unanswered question will help us further understand the regulation and role of Vgll4 in normal and cancer cells. Many members of the Hippo-YAP pathway, including YAP, have been shown previously to be associated with the mitotic machinery and to cause mitotic defects when dysregulated. Therefore, future studies are required to define the role of Vgll4 and its phosphorylation in cell cycle progression, especially in mitosis-related events. Another interesting finding from this study is that Vgll4 is a phospho-protein (multiple bands were observed on Phos-tag gels) (Fig. 1B-D). There is a basal level phosphorylation of Vgll4 that is not regulated by mitotic arrest and is CDK1-independent (Figs. 1, B–D, and 3H), suggesting that in addition to CDK1-mediated mitotic phosphorylation, Vgll4 is phosphorylated by other unknown kinase(s). We are currently investigating this phosphorylation.

Our current study indicates that Vgll4 could down-regulate YAP, BubR1, and MAD2 (Fig. 8, E and H). We previously showed that mitotic phosphorylation of YAP positively regulates MAD2 and BubR1 levels (22). Therefore, it is possible that Vgll4 will control BubR1/MAD2 levels through YAP. It is also interesting that Vgll4 inhibits YAP protein levels in pancreatic cancer cells, an activity that has not been shown in other cancer cell types. The underlying mechanisms of this down-regulation are not known. However, it is unlikely due to the inhibitory phosphorylation of YAP at Ser-127 or Ser-397 as their phosphorylation is also reduced in Vgll4-expressing cells (Fig. 8E). Our future studies will explore how Vgll4 regulates YAP as well as β-catenin. Addressing these questions will not only help understand the biological significance of these proteins in mitosis but also provide insights into their underlying mechanisms in cancer development.

Experimental procedures

Cell culture and transfection

HEK293T, HeLa, HPAF-II, Capan-2, PANC-1, BxPC-3, and Hs776T cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured as ATCC instructed. The cell lines were authenticated at ATCC and were used at low (<25) passages. The immortalized pancreatic epithelial cells (HPNE) were provided by Dr. Michel Ouellette (University of Nebraska Medical Center), who originally established the cell line and deposited it at ATCC (23). The T3M4, S2.013, and Colo-357 pancreatic cancer cell lines were kindly provided by Dr. Michael (Tony) Hollingsworth. The cell lines were maintained as described (24, 25). Attractene (Qiagen) was used for transient overexpression of proteins in HEK293T and HEK293GP cells following the manufacturer's instructions. siRNA transfections were done with HiPerfect (Qiagen). The On-target SMART pool siRNA for Vgll4 was purchased from Dharmacon. Retrovirus or lentivirus packaging, infection, and subsequent selection were done as we have described previously (26). Nocodazole (100 ng/ml for 16 h) and taxol (100 nm for 16 h) (Selleck Chemicals) were used to arrest cells in G2/M phase unless otherwise indicated. Kinase inhibitors were purchased from Selleck Chemicals (VX680, ZM447439, BI2536, Purvalanol A, SP600125, rapamycin, and MK2206), ENZO life Sciences (RO3306 and roscovitine) or LC Laboratory (U0126, SB203580, and LY294002). MK5108 (Aurora-A inhibitor) was from Merck. All other chemicals were from either Sigma or Thermo Fisher.

Expression constructs

The human Vgll4 cDNA has been described (8). To make the retroviral (TetOn-inducible) or Lentiviral Vgll4 expression constructs, the above full-length cDNA was cloned into the Tet-All (27) or pSIN4-FLAG-IRES-puro vector, respectively. The pSIN4-FLAG-IRES-puro vector was made by inserting a FLAG tag with multiple-cloning–site sequences into the pSIN4-IRES-puro vector, which was originally obtained from Addgene (61061; Ref. 28). Myc-TEAD1 was also purchased from Addgene (4). Point mutations were generated by the QuikChange site-directed PCR mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) and verified by sequencing.

Tet-On-inducible expression system

The wild-type or phosphorylation-deficient mutant (4A: S58A/S155A/T159A/S280A) or phosphorylation-mimetic mutant (4D: S58D/S155D/T159D/S280D) Vgll4 cDNA was cloned into the Tet-All vector (27) to generate Tet-On-inducible constructs. Vgll4, Vgll4-4A, or Vgll4-4D expression in BxPC3 cells was achieved by retroviral-mediated infection and selection in a doxycycline-dependent manner. Cells were maintained in medium containing the Tet system-approved fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Clontech Laboratories).

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA isolation, RNA reverse transcription, and quantitative real-time PCR were done as we have described previously (26).

Recombinant protein purification and in vitro kinase assay

GST-tagged Vgll4 and Vgll4-4A were cloned in pGEX-5X-1, and the proteins were bacterially expressed and purified on GSTrap FF affinity columns (GE Healthcare) following the manufacturer's instructions. GST-Vgll4 (0.5–1 μg) was incubated with 10 units of recombinant CDK1–cyclin B complex (New England BioLabs) or 100 ng of CDK1–cyclin B (SignalChem) in kinase buffer (New England BioLabs) in the presence of 7.5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol, PerkinElmer Life Sciences). CDK5–p25, MEK1, ERK1, JNK1, JNK2, and p38α kinases were purchased from SignalChem. Phosphorylation (32P incorporation) was visualized by autoradiography followed by Western blotting or detected by phospho-specific antibodies.

Antibodies

The Vgll4 antibodies were purchased from Abnova (H00009686-B01P). Rabbit polyclonal phospho-specific antibodies against Vgll4 Ser-58, Ser-155/Thr-159, and Ser-280 were generated and purified by AbMart. The peptides used for immunizing rabbits were TGPPI-pS-PSKRK (Ser-58), RPAGL-pS-PTL-pT-PGERQ (Ser-155/Thr-159), and RGQPA-pS-PSAHM (Ser-280). The corresponding non-phosphorylated peptides were also synthesized and used for antibody purification and blocking assays. Anti-FLAG antibody was from Sigma. Anti-Myc, anti-β-actin, and anti-cyclin B antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Aurora-A, glutathione S-transferase (GST), CDK3, and BubR1 antibodies were from Bethyl Laboratories. Phospho-Thr-288/Thr-232/Thr-198 Aurora-A/B/C, phospho-S10 H3, phospho-Ser-127 YAP, phospho-Ser-397 YAP, TAZ, TEAD1, CDC25C, CDK1, CDK4, CDK5, cyclin A2, cyclin E2, MAD2, phospho-Ser-795 Rb, β-catenin, phospho-Ser-33/Ser-37/Thr-41 β-catenin, phospho-Ser-675 β-catenin, Wee1, and phospho-S642 Wee1 antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-β-tubulin (Sigma) antibodies were used for immunofluorescence staining.

Phos-tag and Western blot analysis

Phos-tagTM was obtained from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (catalog #304-93521) and used at 10–20 μm (with 100 μm MnCl2) in 8% SDS-acrylamide gels as described (14). Western blotting, immunoprecipitation, and λ-phosphatase treatment assays were done as previously described (26).

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy

Cell fixation, permeabilization, fluorescence staining, and microscopy were done as previously described (21). For peptide blocking, a protocol from the Abcam website was used as we previously described (16).

Migration and proliferation assays

Wound healing and Transwell assays were utilized for measuring migratory activity as previously described (16, 29). Cell proliferation was determined by MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assays following the manufacturer's instructions (ATCC).

Luciferase reporter assays

Luciferase reporter assays were done as we previously described (24).

Animal studies

For in vivo xenograft studies, S2.013 cells expressing wild-type Vgll4 or Vgll4-4A or BxPC3 cells expressing TetOn-Vgll4 or TetOn-Vgll4-4A (non-phosphorylatable mutant) (1.0 × 106 cells each line) were subcutaneously injected into both flanks of 6-week-old male athymic nude mice (Ncr-nu/nu, Harlan). S2.013 cells were suspended in PBS, and BxPC3 cells were mixed with Matrigel at 1:1 ratio (volume). Five animals were used per group. Doxycycline (0.5 mg/ml in 5% sucrose water) was administered beginning at the time of cancer cell injection. Tumor sizes were measured twice a week using an electronic caliper starting when tumors in the Vgll4-4A group are palpable. Tumor volume (V) was calculated by the formula V = 0.5 × length × width2 (25). Mice were euthanized at the end of the experiment, and the tumors were excised for subsequent analysis. The animals were housed in pathogen-free facilities. All animal experiments were approved by the University of Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was analyzed using a two-tailed, unpaired Student's t test.

Author contributions

J. D. and Y. Z. designed and wrote the paper. Y. Z., S. S., and Y. C. performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and interpreted the results. J. Z., X. C., and Y. C. also provided technical support. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript before submission.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Lei Zhang and Zhaocai Zhou for the Vgll4 cDNA. All fluorescence images were acquired by Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope at the Advanced Microscopy Core at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. The Core is supported in part by Grant P30 GM106397 from the National Institutes of Health. We also thank Dr. Joyce Solheim for critical reading and comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants P30 GM106397 and R01 GM109066 and by Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA036727. This work was also supported by W81XWH-14-1-0150 from the Department of Defense Health Program. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

- YAP

- Yes-associated protein

- TEAD

- TEA-domain protein

- CTGF

- connective tissue growth factor

- Vgll4

- vestigial-like protein 4

- CDK1

- cyclin-dependent kinase 1

- MAD2

- mitotic arrest deficiency 2.

References

- 1. Pan D. (2010) The hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev. Cell 19, 491–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harvey K. F., Zhang X., and Thomas D. M. (2013) The Hippo pathway and human cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 246–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yu F. X., Zhao B., and Guan K. L. (2015) Hippo pathway in organ size control, tissue homeostasis, and cancer. Cell 163, 811–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhao B., Ye X., Yu J., Li L., Li W., Li S., Yu J., Lin J. D., Wang C. Y., Chinnaiyan A. M., Lai Z. C., and Guan K. L. (2008) TEAD mediates YAP-dependent gene induction and growth control. Genes Dev. 22, 1962–1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jiao S., Li C., Hao Q., Miao H., Zhang L., Li L., and Zhou Z. (2017) VGLL4 targets a TCF4-TEAD4 complex to coregulate Wnt and Hippo signalling in colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun. 8, 14058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hansen C. G., Moroishi T., and Guan K. L. (2015) YAP and TAZ: a nexus for Hippo signaling and beyond. Trends Cell Biol. 25, 499–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Koontz L. M., Liu-Chittenden Y., Yin F., Zheng Y., Yu J., Huang B., Chen Q., Wu S., and Pan D. (2013) The Hippo effector Yorkie controls normal tissue growth by antagonizing scalloped-mediated default repression. Dev. Cell 25, 388–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jiao S., Wang H., Shi Z., Dong A., Zhang W., Song X., He F., Wang Y., Zhang Z., Wang W., Wang X., Guo T., Li P., Zhao Y., Ji H., Zhang L., and Zhou Z. (2014) A peptide mimicking VGLL4 function acts as a YAP antagonist therapy against gastric cancer. Cancer Cell 25, 166–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang W., Gao Y., Li P., Shi Z., Guo T., Li F., Han X., Feng Y., Zheng C., Wang Z., Li F., Chen H., Zhou Z., Zhang L., and Ji H. (2014) VGLL4 functions as a new tumor suppressor in lung cancer by negatively regulating the YAP-TEAD transcriptional complex. Cell Res. 24, 331–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li H., Wang Z., Zhang W., Qian K., Liao G., Xu W., and Zhang S. (2015) VGLL4 inhibits EMT in part through suppressing Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in gastric cancer. Med. Oncol. 32, 83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li N., Yu N., Wang J., Xi H., Lu W., Xu H., Deng M., Zheng G., and Liu H. (2015) miR-222/VGLL4/YAP-TEAD1 regulatory loop promotes proliferation and invasion of gastric cancer cells. Am. J. Cancer Res. 5, 1158–1168 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mann K. M., Ward J. M., Yew C. C., Kovochich A., Dawson D. W., Black M. A., Brett B. T., Sheetz T. E., Dupuy A. J., Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative, Chang D. K., Biankin A. V., Waddell N., Kassahn K. S., Grimmond S. M., Rust A. G., Adams D. J., Jenkins N. A., and Copeland N. G. (2012) Sleeping Beauty mutagenesis reveals cooperating mutations and pathways in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 5934–5941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen X., Chen Y., and Dong J. (2016) MST2 phosphorylation at serine 385 in mitosis inhibits its tumor suppressing activity. Cell. Signal. 28, 1826–1832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen X., Stauffer S., Chen Y., and Dong J. (2016) Ajuba phosphorylation by CDK1 promotes cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 14761–14772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang L., Chen X., Stauffer S., Yang S., Chen Y., and Dong J. (2015) CDK1 phosphorylation of TAZ in mitosis inhibits its oncogenic activity. Oncotarget 6, 31399–31412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang S., Zhang L., Liu M., Chong R., Ding S. J., Chen Y., and Dong J. (2013) CDK1 Phosphorylation of YAP promotes mitotic defects and cell motility and is essential for neoplastic transformation. Cancer Res. 73, 6722–6733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ji M., Yang S., Chen Y., Xiao L., Zhang L., and Dong J. (2012) Phospho-regulation of KIBRA by CDK1 and CDC14 phosphatase controls cell-cycle progression. Biochem. J. 447, 93–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Xiao L., Chen Y., Ji M., Volle D. J., Lewis R. E., Tsai M. Y., and Dong J. (2011) KIBRA protein phosphorylation is regulated by mitotic kinase aurora and protein phosphatase 1. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 36304–36315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nigg E. A. (1993) Cellular substrates of p34(cdc2) and its companion cyclin-dependent kinases. Trends Cell Biol. 3, 296–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hornbeck P. V., Zhang B., Murray B., Kornhauser J. M., Latham V., and Skrzypek E. (2015) PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs, and recalibrations. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D512–D520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang L., Iyer J., Chowdhury A., Ji M., Xiao L., Yang S., Chen Y., Tsai M. Y., and Dong J. (2012) KIBRA regulates aurora kinase activity and is required for precise chromosome alignment during mitosis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 34069–34077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yang S., Zhang L., Chen X., Chen Y., and Dong J. (2015) Oncoprotein YAP regulates the spindle checkpoint activation in a mitotic phosphorylation-dependent manner through up-regulation of BubR1. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 6191–6202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee K. M., Yasuda H., Hollingsworth M. A., and Ouellette M. M. (2005) Notch 2-positive progenitors with the intrinsic ability to give rise to pancreatic ductal cells. Lab. Invest. 85, 1003–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yang S., Zhang L., Purohit V., Shukla S. K., Chen X., Yu F., Fu K., Chen Y., Solheim J., Singh P. K., Song W., and Dong J. (2015) Active YAP promotes pancreatic cancer cell motility, invasion and tumorigenesis in a mitotic phosphorylation-dependent manner through LPAR3. Oncotarget 6, 36019–36031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dong J., Feldmann G., Huang J., Wu S., Zhang N., Comerford S. A., Gayyed M. F., Anders R. A., Maitra A., and Pan D. (2007) Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell 130, 1120–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xiao L., Chen Y., Ji M., and Dong J. (2011) KIBRA regulates Hippo signaling activity via interactions with large tumor suppressor kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 7788–7796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yang S., Ji M., Zhang L., Chen Y., Wennmann D. O., Kremerskothen J., and Dong J. (2014) Phosphorylation of KIBRA by the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)-ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) cascade modulates cell proliferation and migration. Cell. Signal. 26, 343–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Elcheva I., Brok-Volchanskaya V., Kumar A., Liu P., Lee J. H., Tong L., Vodyanik M., Swanson S., Stewart R., Kyba M., Yakubov E., Cooke J., Thomson J. A., and Slukvin I. (2014) Direct induction of haematoendothelial programs in human pluripotent stem cells by transcriptional regulators. Nat. Commun. 5, 4372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jube S., Rivera Z. S., Bianchi M. E., Powers A., Wang E., Pagano I., Pass H. I., Gaudino G., Carbone M., and Yang H. (2012) Cancer cell secretion of the DAMP protein HMGB1 supports progression in malignant mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 72, 3290–3301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]