Abstract

Aim:

Fenofibrate, a PPAR-α inhibitor used for treating dyslipidemia, has well-documented anti-inflammatory effects that vary between individuals. While DNA sequence variation explains some of the observed variability in response, epigenetic patterns present another promising avenue of inquiry due to the biological links between the PPAR-α pathway, homocysteine and S-adenosylmethionine – a source of methyl groups for the DNA methylation reaction.

Hypothesis:

DNA methylation variation at baseline is associated with the inflammatory response to a short-term fenofibrate treatment.

Methods:

We have conducted the first epigenome-wide study of inflammatory response to daily treatment with 160 mg of micronized fenofibrate over a 3-week period in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN, n = 750). Epigenome-wide DNA methylation was quantified on CD4+ T cells using the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 array.

Results:

We identified multiple CpG sites significantly associated with the changes in plasma concentrations of inflammatory cytokines such as high sensitivity CRP (hsCRP, 7 CpG sites), IL-2 soluble receptor (IL-2sR, one CpG site), and IL-6 (4 CpG sites). Top CpG sites mapped to KIAA1324L (p = 2.63E-10), SMPD3 (p = 2.14E-08), SYNPO2 (p = 5.00E-08), ILF3 (p = 1.04E-07), PRR3, GNL1 (p = 6.80E-09), FAM50B (p = 3.19E-08), RPTOR (p = 9.79e-07) and several intergenic regions (p < 1.03E-07). We also derived two inflammatory patterns using principal component analysis and uncovered additional epigenetic hits for each pattern before and after fenofibrate treatment.

Conclusion:

Our study provides preliminary evidence of a relationship between DNA methylation and inflammatory response to fenofibrate treatment.

Keywords: : epigenome-wide study, fenofibrate, inflammation, methylation

Fenofibrate is a second generation fibric acid drug derived from the prototype clofibrate. In comparison to first generation drugs, it has improved efficacy and safety [1]. Fenofibrate is an agonist of PPAR-α, and is known to improve lipid profiles, mainly by reducing the levels of triglycerides (TG) and increasing high density lipoprotein cholesterol [2,3]. It has also been shown to reduce systemic inflammation [4–6]. For example, treatment with fenofibrate reduced proinflammatory markers like TNF-α and CRP and improved insulin sensitivity in patients with hypertriglyceridemia [7]. In another study, fenofibrate therapy reduced plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines such as the MCP-1, MIP-1α and IL-1β in patients with hypertriglyceridemia and metabolic syndrome [8]. Effective fenofibrate therapy had a significant inhibitory effect on the release of monocyte-derived inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6 and MCP-1 in patients with type IIb dyslipidemia [9] and hyperlipidemia [10]. Both fenofibrate and simvastatin markedly reduced plasma levels of high-sensitivity CRP (hsCRP), IL-1β and sCD40L in patients with hyperlipidemia [11]. Fenofibrate was also found to be effective in decreasing lipids (total cholesterol, TGs, low density lipoproteins and apolipoprotein B), and cytokines like TNF-α and interferon (IFN)-γ in plasma in patients with atherosclerosis and hyperlipoproteinemia IIb [12]. The anti-inflammatory effect of fenofibrate likely occurs via the very low density lipoprotein and low density lipoprotein mediated pathways, although the exact mechanisms remain to be elucidated in patients with hypertriglyceridemia and metabolic syndrome [8].

The response to fenofibrate treatment is highly variable among individuals. There are very few studies, however, that have investigated the role of genetic variation in the anti-inflammatory effects of fenofibrate treatment. Results from previous analyses of the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network (GOLDN) have shown that common genetic polymorphisms are associated with variation in lipid response to fenofibrate [13–17]. Additionally, several novel biologically relevant loci are shown to be associated with systemic inflammation before and after fenofibrate treatment [18], but no significant predictors of change in individual cytokine concentrations were reported. In a candidate gene study, CRP variants were shown to be associated with response to fenofibrate treatment in participants with metabolic syndrome [19]. Even though the findings of genetic studies have been scant, it is plausible that epigenetic factors like DNA methylation may be a more fruitful area of inquiry due to homocysteine, an important component of the methionine biosynthetic pathway. Fenofibrate has been shown to elevate homocysteine in a PPAR-α dependent manner [20]. Specifically, fenofibrate activates PPAR-α, which in turn increases the expression of enzyme MAT that converts methionine into SAM [21]. SAM undergoes demethylation to form S-adenosyl homocysteine, which is then converted to homocysteine [22]. SAM, thus produced during conversion of methionine to homocysteine, serves as a source of methyl groups required for DNA methylation [23]. Despite the biological plausibility of an epigenetic effect, a previous analysis of GOLDN data [24] has reported that lipid changes due to fenofibrate treatment were not associated with DNA methylation patterns, but no studies to date have explored epigenomic determinants of changes in inflammatory biomarkers following a fenofibrate intervention. To address this gap in evidence, we have conducted the first epigenome-wide study of inflammatory response to fenofibrate treatment, set within a 3-week intervention in GOLDN study participants (n = 750).

Methods

Study design

The GOLDN study recruited families of European ancestry from the field centers of the NHLBI Family Heart Study in Minneapolis, MN and Salt Lake City, UT. It was initiated to assess how genetic contribution to environmental stimuli (diet and drug) influence blood levels of TGs and other atherogenic lipid species as well as inflammatory markers (registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00083369). The GOLDN study investigated genetic determinants of lipid response to two interventions: challenge with a high-fat meal, and treatment with fenofibrate (160 mg) for 3 weeks. For the purposes of this study, we used data from the second intervention. Families with two siblings were recruited and were asked to abstain from lipid lowering agents (nutraceuticals and pharmaceuticals) for at least 4 weeks prior to their first visit. They were also asked to fast for 8 h prior to study visits, and abstain from alcohol 24 h prior to their study visit [18]. Validated questionnaires were used to collect demographic, lifestyle and dietary information. Each participant provided informed consent during the screening visit. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of University of Minnesota, University of Utah, Tufts University/New England Medical Center, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham. More details about the GOLDN study have been published in earlier reports [17–18,25–27]. Baseline and postfenofibrate intervention data were available for 750 participants with DNA methylation measurements. We included all available participants; power was estimated a priori and found sufficient to detect effects >2%.

Measurement of inflammatory biomarkers

For measurement of inflammatory biomarkers in serum, the blood samples were collected from the participants and centrifuged at 2000 × g for 15 min at 4°C within 20 min of collection. The samples were stored at -70°C until analysis. All the samples were analyzed at the same time to rule out variation within the assays. HsCRP was measured on the Hitachi 911 using a latex particle enhanced immunoturbidimetric assay (Kamiya Biomedical Company, WA, USA). IL-6, IL-2 soluble receptor (sR)-α, TNF-α and chemokine MCP-1 were all measured using quantitative sandwich enzyme immunoassay (ELISA kits, R&D systems, MN, USA) according to the protocol from the manufacturer [28].

Estimation of DNA methylation

For estimation of DNA methylation, DNA was extracted using DNeasy kits (Qiagen, CA, USA) from CD4+ T cells purified from buffy coats (from whole blood) using antigen-specific beads (Thermofisher Scientific, MA, USA). Genome-wide DNA methylation was estimated using Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 Bead chip (Illumina Inc., CA, USA) as described in previous studies [29]. Briefly, 500 ng of DNA treated with sodium bisulfite (EZ DNA, Zymo Research, CA, USA) was used to perform the standard Illumina amplification, hybridization and imaging steps. β scores (the proportion of total signal from methylation-specific probe or color channel) and p-values (the probability that the total intensity for a given probe falls within the background signal intensity) were estimated using Illumina Genome Studio. The resulting β scores were normalized using the ComBat package for R software to account for observed batch effects [30]. Random subsets of 10,000 CpGs per run were run after normalization, in which each array of 12 samples were used as batch. Correction for differing probe chemistry was performed on Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 Bead chip, normalizing the probes separately from the Infinium I and II [26,27,29,31]. If the probe sequence in the CpGs mapped either to a location that did not match the annotation file or to >1 locus, they were eliminated. These markers were identified by realigning all probes (with unconverted Cs) to the human reference genome. Methylation data were generated from CpGs after performing quality control (QC) procedures. Principal components (PCs) were generated based on the β-scores of all autosomal CpGs that passed QC by using the prcomp function in R (v2.12.1) [32]. Epigenome-wide DNA methylation was quantified using identical protocols before and after the fenofibrate intervention.

Statistical analysis

Differences in inflammatory biomarker profiles pre- and postfenofibrate intervention were analyzed using paired two-sided t-tests. A total of 244 participants were excluded from the analysis if they were missing outcome or covariate data. Outcomes were defined using ratios of post- to prefenofibrate treatment plasma concentrations of each biomarker (hsCRP, IL-2sR-α, IL-6, MCP1, TNF-α), as well as previously derived [28] inflammatory patterns pre- and postfenofibrate treatment. Log- or square root-transformations were carried out for non-normally distributed ratios. For the model with the strongest evidence of association, a sensitivity analysis was conducted with the outcome defined as the difference in post- and prefenofibrate treatment concentrations rather than a ratio, adjusting for baseline values. PC analysis (PROC FACTOR in SAS) was used to derive inflammatory patterns [33]. All five inflammatory biomarkers were measured before fenofibrate treatment, and entered into the model, to produce two inflammatory patterns based on evaluation of eigenvalues and the Scree plot [28]. Interpretability was improved by rotating the patterns using the VARIMAX option [34]. For derivation of postfenofibrate inflammatory patterns, the procedure was repeated with the same markers measured in fasting serum collected at the end of the intervention.

To remove the confounding due to T-cell impurity in DNA methylation profiles, residuals of methylation were obtained by entering the four PCs derived from whole-genome methylation as fixed effects in linear mixed models [24]. In sensitivity analyses, additional adjustments were made for lifestyle factors that may modify DNA methylation, including smoking (current smoking yes or no), alcohol consumption (in grams per day) and BMI (kg/m2). Bonferroni correction was used to account for multiple comparisons, with the genome-wide significance level of 0.05/(number of CpGs or 450,000) = 1.1 × 10-7. Manhattan plots were constructed to visualize the results. To evaluate deviations from the expected test statistic distributions, quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plots were constructed. All the datasets on which the conclusion of report relies are available on request.

Results

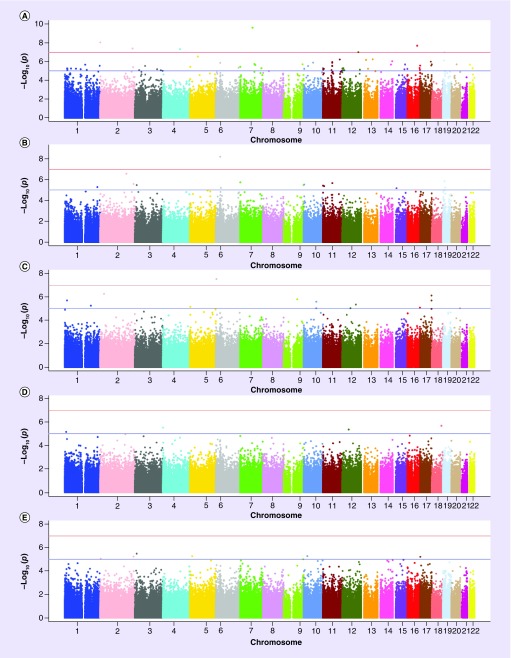

General characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. At baseline, the mean age of participants was 48 ± 16 years; about half of the participants were female. All participants were of self-reported European ancestry. Paradoxically, serum concentrations of all inflammatory biomarkers except hsCRP slightly increased from baseline to postfenofibrate treatment (Table 1). The data meet the assumption of the tests. The top loci associated with the post- to prefenofibrate treatment ratio for each inflammatory biomarker are described in Table 2. We identified seven CpGs significantly associated with hsCRP, one with IL-2sR and four with IL-6 (Table 2). The Manhattan plots summarizing the results of the epigenome-wide analyses for each outcome are shown in Figure 1. The quantile–quantile (Q–Q) plots were used to summarize the results of the epigenome-wide analyses for each outcome (data not shown). The following lambda values were estimated for each model, indicating modest deviations for all phenotypes except for CRP: 1.22 (hsCRP ratio), 1.08 (IL-2sR-α ratio), 1.01 (IL-6 ratio), 0.98 (MCP-1 ratio) and 1.03 (TNF-α ratio). There was no meaningful change in the results after sensitivity analysis after adjustment for alcohol, smoking and BMI (Supplementary Table 1). Consistent with previous reports by Kabagambe et al. and Aslibekyan et al. [18,28], two inflammatory patterns were identified each before and after fenofibrate treatment: hsCRP-IL6 (Factor 1) and MCP1-TNF-α (Factor 2). The two top hits for Factor 1 prefenofibrate treatment were BCL2L15 and KCNQ1, and BCL2L15 and GRIA4 emerged as top epigenetic correlates of Factor 2 postfenofibrate treatment. There were no significant hits for postfenofibrate treatment for Factor 1 and for prefenofibrate treatment Factor 2 (Supplementary Table 2). These hits were not consistent with those found for individual cytokines.

Table 1. . Characteristics of the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network study participants (n = 750).

| Variable | Baseline (n = 750) | After 3 weeks (n = 750) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48.90 (15.97) | – | |

| Sex (% female) | 49.7 | – | |

| High sensitivity C-reactive protein (mg/dl) | 0.24 (0.35) | 0.26 (0.47) | 0.20 |

| IL-2 soluble receptor-α (pg/ml) | 1015.80 (359.37) | 1163.30 (534.58) | <0.0001 |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | 2.07 (3.62) | 2.23 (3.55) | 0.009 |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | 3.51 (6.10) | 3.79 (4.22) | 0.002 |

| MCP-1 (pg/ml) | 208.49 (68.31) | 224.03 (76.92) | <0.0001 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or N (%).

Table 2. . Top loci associated with inflammatory response to ratio of pre- and postfenofibrate treatment in Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network study participants.

| CpG site | CHR | Genes | BP | BETA | SE | p-value | n | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg22616933 | 7 | KIAA1324L | 86547833 | -55.88 | 8.72 | 2.63E-10 | 749 | ratio_crp |

| cg13215593 | 2 | – | 558823 | -23.32 | 4.01 | 9.45E-09 | 738 | ratio_crp |

| cg05591728 | 16 | SMPD3 | 68477022 | -47.30 | 8.35 | 2.14E-08 | 749 | ratio_crp |

| cg09245319 | 2 | – | 227049703 | -73.22 | 13.21 | 4.22E-08 | 749 | ratio_crp |

| cg14717666 | 4 | SYNPO2 | 119862992 | 32.46 | 5.89 | 5.00E-08 | 748 | ratio_crp |

| cg08623156 | 12 | – | 113577046 | -41.66 | 7.75 | 1.03E-07 | 749 | ratio_crp |

| cg18630811 | 19 | ILF3 | 10791805 | -83.20 | 15.48 | 1.04E-07 | 748 | ratio_crp |

| cg18221028 | 6 | PRR3; GNL1 | 30523418 | 11.91 | 2.03 | 6.80E-09 | 748 | ratio_il2 |

| cg27445347 | 6 | FAM50B | 3849801 | -6.64 | 1.19 | 3.19E-08 | 749 | ratio_il6 |

| cg06343673 | 17 | RPTOR | 78778232 | -1.34 | 0. 27 | 9.79E-07 | 749 | ratio_il6 |

| cg13098428 | 17 | RPTOR | 78775814 | -1.36 | 0.28 | 2.03E-06 | 749 | ratio_il6 |

| cg16896879 | 17 | RPTOR | 78778094 | -6.58 | 1.45 | 6.71E-06 | 749 | ratio_il6 |

Figure 1. . Manhattan plots of the epigenome-wide association study in Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network participants.

Manhattan plots of genome-wide results of testing for association between CpGs and Inflammatory response to ratio of pre- and postfenofibrate treatment (A–E) inflammatory patterns. The X-axes display the chromosome on which the CpG is located, the Y-axes display −log10 (p-value). (A) High-sensitivity CRP; (B) IL-2 soluble receptor-α; (C) IL-6; (D) MCP-1; (E) TNF-α

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the epigenomic determinants of changes in inflammatory biomarkers following a fenofibrate intervention. Among individual inflammatory biomarkers’ response to fenofibrate, the strongest association was found for CpG associated with the CRP-IL-2sR pattern, located in KIAA1324L (chromosome 7). Human KIAA1324L, or EIG121L, is markedly downregulated by a constitutively active mutant of Ras [35]. At least seven of the top ten genes shown to interact with KIAA1324L were related to inflammation: DLC1, ERBB4, PDCD4, TSPAN3, RPS23, ESR1, TCEAL4 and PDE5A [36]. DLC1 is a tumor suppressor gene, absence of which results in inflammation in gastric cancer [37]. ERBB4 has been shown to function both as an oncogene as well as a tumor suppressor gene. Over-expression of ERBB2 has been shown to enhance cellular transformation in human colon cancer [38]. Loss of ERBB4 led to exacerbation of acute or chronic inflammation in mouse models of liver injury [39]. PDCD4 is a neoplastic transformation inhibitor and thus acts as a tumor suppressor but inhibiting tumor promoter-induced neoplastic transformation that is usually driven by inflammation [40]. RPS23 belongs to the family of ribosomal proteins, and is found to be optimal in bowel inflammation and cancer [41]. ESR1 is one form of the estrogen receptor that is involved in inflammation and cancer [42,43]. TCEAL4 is a transcription elongation factor that is downregulated in thyroid cancer [44]. PDE5A is an enzyme from the phosphodiesterase class, and has been recently discovered to downregulate inflammatory cytokines partially through the activation of Akt signaling pathway [45].

Other strong associations were found for IL-2sR, specifically at cg18221028 near PRR3, GNL1 and for IL-6, namely at cg27445347 near FAM50B (all on chromosome 6). Pseudo response regulator 3 (PRR3) transcript levels vary in a circadian pattern with peak expression at dusk under long and short day conditions [46]. Of the ten top genes interacting with PRR3, five (GCN20, ABCF1, TRIM27, BLMH and LIG3) were associated with inflammation [36]. GNL1, a putative nucleolar GTPase, belongs to the MMR1-HSR1 family of large GTPases that are emerging as crucial coordinators of signaling cascades in different cellular compartments [47]. Additional associations that were approaching statistical significance were found for CpGs (cg06343673, cg13098428 and cg16896879) associated with IL-6, near RPTOR (chromosome 17). RPTOR is involved in the control of the mTORC1 activity which regulates cell growth and survival, and autophagy in response to nutrient and hormonal signals; functions as a scaffold for recruiting mTORC1 substrates. mTORC1 is activated in response to growth factors or amino acids. Growth factor-stimulated mTORC1 activation involves AKT1-mediated phosphorylation of TSC1-TSC2, which leads to the activation of the RHEB GTPase that potently activates the protein kinase activity of mTORC1 [48,49]. Several studies have demonstrated an important role for RPTOR in regulation of inflammation in various diseased conditions. Micro RNA (miR)-155 has been shown to target RPTOR in lung epithelial cells from patients with cystic fibrosis [50]. The disruption of mTORC1 signaling in macrophages had a protective effect against inflammation and insulin resistance [51]. In another study, treatment with rapamycin or hepatocyte-specific ablation of Raptor resulted in increased levels of IL-6 production, activation of signal transducer and activator of STAT3, and increase in development of hepatocellular carcinoma [52]. mTOR signal pathway activation resulted in activation of TLR-4 during THP-1 macrophage foam cells formation [53].

To date, few pharmacogenomic studies have evaluated the role of methylation in the inflammatory response. An 8-week daily supplementation with 200 mg oligomeric flavonoids from grape seeds did not cause major changes of DNA methylation state but influenced the expression of genes associated with cardiovascular disease pathways [54]. SAM is a methyl donor in DNA methylation, and has been shown to lower lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of the proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α and increase the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in macrophages. SAM was found to modulate the expression of inflammatory genes in association with changes in specific gene promoter DNA methylation [55]. Treatment with folic acid (FA)/B12 was found to be associated with more rapid progression of coronary artery disease (CAD). ADMA and TML are both produced by post-translational SAM-dependent methylation of precursor amino acid via proteolytic release. In patients with established CAD, baseline ADMA and TML was associated with angiographic progression of CAD, but treatment with FA/B12 (± B6) did not alter the levels of neither ADMA nor TML [56].

Epigenetic regulators are shown to be involved in histone acetylating and deacetylating activities that contribute to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and restenosis. Since these alterations in chromatin structure are reversible, these epigenetic modifications can be subjected to pharmacological intervention for the management of cardiovascular diseases [57]. Plaques preferentially develop in arterial regions of disturbed blood flow (d-flow), thus altering endothelial gene expression and function. D-flow was found to regulate genome-wide DNA methylation patterns in a DNA methyltransferase-dependent manner. This was followed by alteration of endothelial gene expression and induction of atherosclerosis [58]. Finally, a previous analysis of GOLDN data reported that lipid changes due to fenofibrate treatment are not associated with changes in DNA methylation patterns [24], although it did not investigate baseline methylation as a potential predictor. Overall, our study provides a unique perspective on the modulation of inflammatory biomarkers by fenofibrate and its association with epigenomic determinants.

There are several limitations of our study. First, the current study was only conducted in one cohort, and false positive results remain a concern. Replication of gene–drug response associations are costly and are logistically difficult to conduct, but can markedly improve the quality of published studies by minimizing false-positive findings. However, approaches like functional validation, combined analysis of several populations and simulations could provide an all-encompassing and scrupulous path for validating the findings from studies on genetic association [59]. Future studies should consider these alternative approaches to follow-up of our preliminary findings. Second, in the current epigenome-wide study, we were limited to interrogating DNA methylation in genomic regions included on the Illumina 450K array. It is possible that methylation patterns beyond those quantified by the array may also influence response to fenofibrate. Third, we only quantified methylation on CD4+ T cells (the most abundant lymphocyte in whole blood) to limit confounding by cell type. Thus, future studies may consider other relevant cell types, for example, monocytes, to test the generalizability of our findings.

Conclusion

Fenofibrate is a lipid lowering drug, and has been reported to reduce inflammation. Our group had previously identified several biologically relevant loci that were associated with inflammation. In this study, we investigated the epigenomic determinants of changes in inflammatory biomarkers after fenofibrate intervention. We found that several CpG sites were associated with change in plasma concentrations of inflammatory cytokines, namely hsCRP, IL-2sR and IL-6. We also found additional hits for each inflammatory pattern before and after fenofibrate treatment. The findings from our study provide basis for relationship between DNA methylation and fenofibrate treatment.

Summary points.

We conducted the first study of epigenomic determinants of changes in inflammatory biomarkers following a fenofibrate intervention.

A total of seven CpG sites were found to be significantly associated with hsCRP, one with IL-2sR, and four with IL-6.

The strongest association was found for the CpG site associated with the CRP-IL-2sR pattern, located in KIAA1324L (chromosome 7).

Seven of the top ten genes shown to interact with KIAA1324L were related to inflammation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This research was funded by NIH grant R01 HL104135. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Wu TJ, Ou HY, Chou CW, Hsiao SH, Lin CY, Kao PC. Decrease in inflammatory cardiovascular risk markers in hyperlipidemic diabetic patients treated with fenofibrate. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2007;37(2):158–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoonjans K, Staels B, Auwerx J. The peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARS) and their effects on lipid metabolism and adipocyte differentiation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1996;1302(2):93–109. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(96)00066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Staels B, Schoonjans K, Fruchart JC, Auwerx J. The effects of fibrates and thiazolidinediones on plasma triglyceride metabolism are mediated by distinct peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARs) Biochimie. 1997;79(2–3):95–99. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(97)81497-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen J, Ordovas JM. Impact of genetic and environmental factors on hsCRP concentrations and response to therapeutic agents. Clin. Chem. 2009;55(2):256–264. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.117754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Libby P, Plutzky J. Inflammation in diabetes mellitus: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha and peroxisome-activated receptor-gamma agonists. Am. J. Cardiol. 2007;99(4A):27B–40B. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bragt MCE, Mensink RP. Comparison of the effects of n-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids and fenofibrate on markers of inflammation and vascular function, and on the serum lipoprotein profile in overweight and obese subjects. Nut. Met. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2012;22(11):966–973. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh KK, Quon MJ, Lim S, et al. Effects of fenofibrate therapy on circulating adipocytokines in patients with primary hypertriglyceridemia. Atherosclerosis. 2011;214(1):144–147. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenson RS, Huskin AL, Wolff DA, Helenowski IB, Rademaker AW. Fenofibrate reduces fasting and postprandial inflammatory responses among hypertriglyceridemia patients with the metabolic syndrome. Atherosclerosis. 2008;198(2):381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okopień B, Kowalski J, Krysiak R, et al. Monocyte suppressing action of fenofibrate. Pharmacol. Rep. 2005;57(3):367–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kowalski J, Okopień B, Madej A, Zieliński M, Belowski D, Kalina Z, Herman ZS. Effects of atorvastatin, simvastatin, and fenofibrate therapy on monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 secretion in patients with hyperlipidemia. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2003;59(3):189–193. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0581-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang TD, Chen WJ, Lin JW, Cheng CC, Chen MF, Lee YT. Efficacy of fenofibrate and simvastatin on endothelial function and inflammatory markers in patients with combined hyperlipidemia: relations with baseline lipid profiles. Atherosclerosis. 2003;170(2):315–323. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(03)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madej A, Okopien B, Kowalski J, et al. Effects of fenofibrate on plasma cytokine concentrations in patients with atherosclerosis and hyperlipoproteinemia IIb. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1998;36(6):345–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Ordovas JM, Gao G, et al. Pharmacogenetic association of the APOA1/C3/A4/A5 gene cluster and lipid responses to fenofibrate: the Genetics of Lipid-Lowering Drugs and Diet Network study. Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 2009;19(2):161–169. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32831e030e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai CQ, Arnett DK, Corella D, et al. Fenofibrate effect on triglyceride and postprandial response of apolipoprotein A5 variants: the GOLDN study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007;27(6):1417–1425. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.140103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai MY, Ordovas JM, Li N, et al. Effect of fenofibrate therapy and ABCA1 polymorphisms on high-density lipoprotein subclasses in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drugs and Diet Network. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2010;100(2):118–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wojczynski MK, Gao G, Borecki I, et al. Apolipoprotein B genetic variants modify the response to fenofibrate: a GOLDN study. J. Lipid Res. 2010;51:3316–3323. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P001834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frazier-Wood AC, Ordovas JM, Straka RJ, et al. The PPAR alpha gene is associated with triglyceride, low-density cholesterol and inflammation marker response to fenofibrate intervention: the GOLDN study. Pharmacogenomics J. 2013;13(4):312–317. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2012.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aslibekyan S, Kabagambe EK, Irvin MR, et al. A genome-wide association study of inflammatory biomarker changes in response to fenofibrate treatment in the Genetics of Lipid Lowering Drug and Diet Network. Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 2012;22(3):191–197. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32834fdd41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shen J, Arnett DK, Parnell LD, et al. Association of common C-reactive protein (CRP) gene polymorphisms with baseline plasma CRP levels and fenofibrate response: the GOLDN study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(5):910–915. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foucher C, Brugére L, Ansquer JC. Fenofibrate, homocysteine and renal function. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2010;8(5):589–603. doi: 10.2174/157016110792006987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luc G, Jacob N, Bouly M, Fruchart J-C, Staels B, Giral P. Fenofibrate increases homocystinemia through a PPAR-α-mediated mechanism. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2004;43:452–453. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200403000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang M, Vousden KH. Serine and one-carbon metabolism in cancer. Nature. 2016;16:650–662. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obeid R. The metabolic burden of methyl donor deficiency with focus on the betaine homocysteine methyltransferase pathway. Nutrients. 2013;5(9):3481–3495. doi: 10.3390/nu5093481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das M, Irvin MR, Sha J, et al. Lipid changes due to fenofibrate treatment are not associated with changes in DNA methylation patterns in the GOLDN study. Front. Genet. 2015;6:304. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2015.00304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feitosa MF, An P, Ordovas JM, et al. Association of gene variants with lipid levels in response to fenofibrate is influenced by metabolic syndrome status. Atherosclerosis. 2011;215(2):435–439. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hidalgo B, Irvin MR, Sha J, et al. Epigenome-wide association study of fasting measures of glucose, insulin, and HOMA-IR in the genetics of lipid lowering drugs and diet network study. Diabetes. 2014;63(2):801–807. doi: 10.2337/db13-1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irvin MR, Zhi D, Joehanes R, et al. Epigenome-wide association study of fasting blood lipids in the Genetics of Lipid-Lowering Drugs and Diet Network study. Circulation. 2014;130(7):565–572. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kabagambe EK, Ordovas JM, Tsai MY, et al. Smoking, inflammatory patterns and postprandial hypertriglyceridemia. Atherosclerosis. 2009;203(2):633–639. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Absher DM, Li X, Waite LL, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis of systemic lupus erythematosus reveals persistent hypomethylation of interferon genes and compositional changes to CD4+ T-cell populations. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(8):e1003678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen C, Grennan K, Badner J, et al. Removing batch effects in analysis of expression microarray data: an evaluation of six batch adjustment methods. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(2):e17238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aslibekyan S, Demerath EW, Mendelson M, et al. Epigenome-wide study identifies novel methylation loci associated with body mass index and waist circumference. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2015;23(7):1493–1501. doi: 10.1002/oby.21111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Visscher H, Ross CJ, Dubé MP, et al. 2009. Application of principal component analysis to pharmacogenomic studies in Canada. Pharmacogenomics J. 2009;9(6):362–372. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2009.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atkinson B, Therneau T. The kinship package (for R). Software copyright Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. 2003. http://ftp.uni-bayreuth.de/math/statlib/R/CRAN/doc/packages/kinship.pdf

- 34.Hu FB, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, Ascherio A, Spiegelman D, Willett WC. Prospective study of major dietary patterns and risk of coronary heart disease in men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000;72(4):912–921. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.4.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Araki T, Kusakabe M, Nishida E. A transmembrane protein EIG121L is required for epidermal differentiation during early embryonic development. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286(8):6760–6768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.177907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greene CS, Krishnan A, Wong AK, et al. Understanding multicellular function and disease with human tissue-specific networks. Nat. Genetics. 2015;47(6):569–576. doi: 10.1038/ng.3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hitkova I, Yuan G, Anderl F, et al. Caveolin-1 protects B6129 mice against Helicobacter pylori gastritis. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(4):e10032351. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams CS, Bernard JK, Demory Beckler M, et al. ERBB4 is over-expressed in human colon cancer and enhances cellular transformation. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36(7):710–718. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, Zhou Q, He XS, et al. Genetic variants in ERBB4 is associated with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Oncotarget. 2016;7(4):4981–4992. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang L, Zhao M, Guo C, et al. PDCD4 deficiency aggravated colitis and colitis-associated colorectal cancer via promoting IL-6/STAT3 pathway in mice. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2016;22(5):1107–1118. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krzystek-Korpacka M, Diakowska D, Bania J, Gamian A. Expression stability of common housekeeping genes is differently affected by bowel inflammation and cancer: implications for finding suitable normalizers for inflammatory bowel disease studies. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2014;20(7):1147–1156. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Murray JI, West NR, Murphy LC, Watson PH. Intratumoral inflammation and endocrine resistance in breast cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2015;22(1):R51–R67. doi: 10.1530/ERC-14-0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Asztalos S, Pham TN, Gann PH, Hayes MK, Deaton R, Wiley EL. High incidence of triple negative breast cancers following pregnancy and an associated gene signature. Springerplus. 2015;4:710. doi: 10.1186/s40064-015-1512-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Akaishi J, Onda M, Okamoto J, et al. Down-regulation of transcription elongation factor A (SII) like 4 (TCEAL4) in anaplastic thyroid cancer. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:260. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li L, Zhao D, Jin Z, Zhang J, Paul C, Wang Y. Phosphodiesterase 5a inhibition with adenoviral short hairpin RNA benefits infarcted heart partially through activation of Akt signaling pathway and reduction of inflammatory cytokines. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0145766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Para A, Farré EM, Imaizumi T, Pruneda-Paz JL, Harmon FG, Kay SA. PRR3 is a vascular regulator of TOC1 stability in the Arabidopsis circadian clock. Plant Cell. 2007;19(11):3462–3473. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boddapati N, Anbarasu K, Suryaraja R, Tendulkar AV, Mahalingam S. Subcellular distribution of the human putative nucleolar GTPase GNL1 is regulated by a novel arginine/lysine-rich domain and a GTP binding domain in a cell cycle-dependent manner. J. Mol. Biol. 2012;416(3):346–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim DH, Sarbassov DD, Ali SM, et al. mTOR interacts with raptor to form a nutrient-sensitive complex that signals to the growth machinery. Cell. 2002;110(2):163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00808-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hara K, Maruki Y, Long X, et al. Raptor, a binding partner of target of rapamycin (TOR), mediates TOR action. Cell. 2002;110(2):177–189. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00833-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsuchiya M, Kalurupalle S, Kumar P, et al. RPTOR, a novel target of miR-155, elicits a fibrotic phenotype of cystic fibrosis lung epithelium by upregulating CTGF. RNA Biol. 2016;13(9):837–847. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1197484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang H, Westerterp M, Wang C, Zhu Y, Ai D. Macrophage mTORC1 disruption reduces inflammation and insulin resistance in obese mice. Diabetologia. 2014;57(11):2393–2404. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Umemura A, Park EJ, Taniguchi K, et al. Liver damage, inflammation, and enhanced tumorigenesis after persistent mTORC1 inhibition. Cell Metab. 2014;20(1):133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu M, Kang X, Xue H, Yin H. Toll-like receptor 4 is up-regulated by mTOR activation during THP-1 macrophage foam cells formation. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 2011;43(12):940–947. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmr093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Milenkovic D, Vanden Berghe W, Boby C, et al. Dietary flavanols modulate the transcription of genes associated with cardiovascular pathology without changes in their DNA methylation state. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(4):e95527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pfalzer AC, Choi SW, Tammen SA, Park LK, Bottiglieri T, Parnell LD, Lamon-Fava S. S-adenosylmethionine mediates inhibition of inflammatory response and changes in DNA methylation in human macrophages. Physiol. Genomics. 2014;46(17):617–623. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00056.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Løland KH, Bleie O, Borgeraas H, et al. The association between progression of atherosclerosis and the methylated amino acids asymmetric dimethylarginine and trimethyllysine. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e64774. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pons D, de Vries FR, van den Elsen PJ, Heijmans BT, Quax PH, Jukema JW. Epigenetic histone acetylation modifiers in vascular remodelling: new targets for therapy in cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 2009;30(3):266–277. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dunn J, Qiu H, Kim S, Jjingo D, Hoffman R, Kim CW, et al. Flow-dependent epigenetic DNA methylation regulates endothelial gene expression and atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;12(7):3187–3199. doi: 10.1172/JCI74792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chanock SJ, Manolio T, Boehnke M, Boerwinkle E, Hunter DJ, Thomas G, et al. Replicating genotype-phenotype associations. Nature. 2007;447(7145):655–660. doi: 10.1038/447655a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.