Abstract

Food and nutrition insecurity becomes increasingly worse in areas affected by armed conflict. Children affected by conflict, or in war-torn settings, face a disproportionate burden of malnutrition and poor health outcomes. As noted by humanitarian response reviews, there is a need for a stronger evidence-based response to humanitarian crises. To achieve this, we systematically searched and evaluated existing nutrition interventions carried out in conflict settings that assessed their impact on children’s nutrition status. To evaluate the impact of nutrition interventions on children’s nutrition and growth status, we identified published literature through EMBASE, PubMed, and Global Health by using a combination of relevant text words and Medical Subject Heading terms. Studies for this review must have included children (aged ≤18 y), been conducted in conflict or postconflict settings, and assessed a nutrition intervention that measured ≥1 outcome for nutrition status (i.e., stunting, wasting, or underweight). Eleven studies met the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this review. Five different nutrition interventions were identified and showed modest results in decreasing the prevalence of stunting, wasting, underweight, reduction in severe or moderate acute malnutrition or both, mortality, anemia, and diarrhea. Overall, nutrition interventions in conflict settings were associated with improved children’s nutrition or growth status. Emergency nutrition programs should continue to follow recent recommendations to expand coverage and access (beyond refugee camps to rural areas) and ensure that aid and nutrition interventions are distributed equitably in all conflict-affected populations.

Keywords: nutrition aid, humanitarian emergencies, humanitarian aid, conflict settings, emergency settings, nutritional status, malnutrition, therapeutic feeding, nutrition interventions, conflict zones

Introduction

Food and nutrition insecurity becomes increasingly worse in areas affected by armed conflict (1, 2). Global humanitarian aid agencies are currently faced with an unprecedented number of food insecurity and hunger crises. The International Food Policy Research Institute estimates that ∼112 million malnourished children live in conflict (i.e., war-torn) affected areas—a number that accounts for two-thirds of all malnourished children in poor countries (1). According to the US Agency for International Development’s Famine Early Warning Systems Network, >70 million people across 45 countries will face acute food insecurity as a result of persistent conflict, severe drought, and economic instability and will require emergency food assistance during 2017 (2). Many are forced to leave their homes and become refugees (i.e., resettle outside their country’s borders) or are internally displaced (i.e., resettle within their country’s borders) (1). The destruction of agricultural infrastructure, attacks on health care facilities and humanitarian aid convoys, infectious disease outbreaks, conflict-related sanctions by countries, unsafe water, poor sanitation and hygiene, and a vicious cycle of violence, poverty, and deprivation all contribute to public health emergencies in conflict settings (1, 3).

Malnutrition stunts children’s growth, deprives them of essential vitamins and minerals, and makes them more susceptible to infectious and chronic diseases. Nearly half of all deaths in children <5 y old can be attributed to undernutrition and are associated with a combination of risk factors, including the following: insufficient protein, energy, and micronutrients; frequent infections or infectious diseases; poor care and feeding practices; inadequate health services; and poor water and sanitation (4). Combating malnutrition is challenging in areas of violent conflict and disproportionately affects women and children (3, 4). The burden faced by children is evident from nutritional deficiencies reported in current conflict-affected areas. For example, an estimated 244,000 children in Borno State, Nigeria, were suffering from severe acute malnutrition (SAM) due to violence and mass displacement caused by the Boko Haram insurgency in 2016 (5). It was estimated that, on average, 134 children in the Borno State living under conflict conditions would die every day from issues related to malnutrition, which shows the urgency of scaling up humanitarian aid in conflict-affected populations (5). In South Sudan, a country engulfed in conflict since 2013, ∼362,077 children are suffering from SAM, with the number rapidly increasing (6). In Yemen, a war-torn country in the Middle East, almost half of all children aged <5 y are chronically malnourished and 320,000 are at risk of SAM (3). Recent cholera outbreaks in both Yemen and South Sudan have further exacerbated the vulnerability of children and the risk of malnutrition (6).

It is evident that adequate nutrition, sanitation, and hygiene during conflict and in emergency settings are crucial factors in preventing malnutrition and growth deficiencies in children. When implemented, nutrition interventions in emergency and refugee settings should reduce the prevalence of malnutrition, underweight, stunting, and wasting in children (i.e., ≤18 y old). The purpose of this narrative systematic review was to identify the types of nutrition interventions carried out in conflict and postconflict settings and to evaluate the associations between these interventions and children’s nutritional and growth status.

Current Status of Knowledge

Nutrition in conflict zones

Impact of conflict on food insecurity.

Household food insecurity is an important factor contributing to poor nutritional status among children during conflict and is associated with the risk of stunting and underweight in children (7). Coping strategies commonly used by refugees include reducing portion sizes and frequency of meals, spending less on food, and borrowing food (7, 8). In addition, during times of conflict, food quantity is prioritized over food quality (8). Children born during conflict are particularly vulnerable to adverse long-term health outcomes, such as severe malnutrition and psychiatric disorders including post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, and dissociative disorders, which affect their overall development (8–10). Studies also show that, during conflict, women tend to stop breastfeeding, which further deprives children of the nutrition and protective effects conferred by breast milk (9, 11). Interventions designed to support breastfeeding among women affected by conflict have not been shown to be as effective as those under nonconflict conditions, in part due to stress and interference in mass distribution of breast-milk substitutes, including formula, via humanitarian aid (9, 11). Food shortages and access to adequate food and safe water remain a major concern for refugees living in conflict zones, which makes them highly dependent on food imports (8). Widespread hunger is prevalent in conflicts settings where preventing access to food is often used as a weapon of war. This results from the destruction of agricultural infrastructure and blocking humanitarian aid. In addition, countries may have difficulty importing food as a result of international sanctions, and corresponding food price inflation as a result of scarcity (8, 9). The food that eventually becomes available either via the black market or an underground food network is sold at dramatically inflated prices (8).

Nutrition interventions in emergency settings and challenges in evaluating their impact.

Nutrition interventions provided by governments and relief agencies in general emergency settings have previously been reviewed (12, 13). General emergency settings of these interventions were the result of chronic or sudden natural disasters, disease epidemics, political or economic crisis, or the breakdown of order and institutions due to public unrest, government collapse, or war (12, 13). Generally, interventions used to treat micronutrient deficiencies and malnutrition included the following: general food distributions, blanket supplementary feeding programs for vulnerable groups, targeted supplementary feeding programs, micronutrient distribution, agricultural support, and infant and young child feeding programs (12, 13). Several nutrition interventions targeting malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies were found to be effective in the stable and development phases of emergencies (i.e., refugee camps) on malnutrition, vitamin deficiencies, and standard anthropometric measurements (13). Findings were less consistent for anthropometric outcomes in all contexts, which indicates the need for quality research examining the effects of these interventions on stunting and other forms of malnutrition (12, 13). Specifically, both reviews emphasized a need for stronger evidence in evaluating the impact of nutrition interventions on children’s health and development in humanitarian crises in unstable settings. Because there is consensus on an evidence gap on the effects of nutrition interventions on malnutrition and stunting in conflict settings, our narrative review assesses the potential impact of different types of nutrition interventions to promote nutrition and growth status in children conducted in conflict settings.

Due to challenges with conducting research in emergency settings, program decisions have often been based on anecdotal evidence and intuition (12). Representatives from the World Food Program and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees have highlighted the challenges of designing studies to evaluate the impact of the interventions in emergency settings (14, 15). Due to ethical considerations, security, logistics, and the nature of emergency settings, most studies adopt a plausibility design, which includes pre- and postintervention cross-sectional surveys, prospective cohort designs, step-wedge designs, and the inclusion of a nontargeted group to compare changes, rather than randomized controlled trials (14, 16).

Evaluating nutrition interventions on malnutrition and growth in conflict settings

To evaluate existing nutrition interventions explicitly in conflict and postconflict settings, a literature search protocol was prepared on the basis of clearly defined a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for this review1

| Criteria | Qualifications |

| Studies | Randomized controlled trials, cross-sectional studies, or cohort studies in which there was an aim to promote the nutritional status of children to decrease physical adverse effects due to lack of adequate nutrition caused by living in conflict settings. Studies could have measured the prevalence of anemia, diarrhea, infectious diseases, or mortality. If the study included a control group, it was defined as a comparison group. Studies were not included if they did not include the assessment of a nutrition intervention with a comparison group or baseline measurements. |

| Participants | Studies were included if the study participants were children aged ≤18 y who were living in a conflict zone or postconflict setting. Studies were not included if they did not include children aged ≤18 y. |

| Settings | Studies were included if the intervention was conducted during conflict or postconflict in war zones or in resettlement or refugee camps. |

| Interventions | Studies were included if the intervention included a nutritional component that promoted nutritional status or growth recovery. The study must have included ≥1 indicator of growth or measurement of nutritional status. These included the following: wasting (weight-for-height), stunting (height-for-age), and underweight (weight-for-age). Studies could have also reported the recovery from MAM or SAM, if measured by one of the growth indicators. Secondary measurements could have included the prevalence of anemia, diarrhea, or mortality. |

| Outcome measures | Studies were included if the primary outcome of interest affected the individual’s nutritional or growth status and was measured by a standardized and validated method (e.g., NCHS, CDC, or WHO growth reference standards). Studies were not included if they did not report ≥1 quantitative value for the primary outcomes of interest. |

MAM, moderate acute malnutrition; NCHS, National Center for Health Statistics; SAM, severe acute malnutrition.

Study selection criteria and search methods for narrative review.

A search of 3 databases [PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/), Global Health (http://www.ovid.com/site/catalog/databases/30.jsp), and EMBASE (http://ovid.com/site/catalog/databases/903.jsp)] was completed by using database-specific Medical Subject Heading terms through 1 February 2017. Reference lists of selected articles were also searched to find additional studies related to the topic. Relevant literature was identified by using the following key topic areas: conflict zones, children (≤18 y old), nutrition interventions, and nutrition indicators. Under each area of focus, search terms were used to generate an electronic search strategy tailored to each database (Table 2). The studies identified from each search were imported into EndNote X7 (Thompson Reuters) where duplicates were removed.

TABLE 2.

Key topic areas used to identify literature in the databases (EMBASE, PubMed, and Global Health)1

| Conflict zones | Children (≤18 y) | Nutrition intervention | Nutrition indicators |

| Armed conflict | Adolescent | Diet | Body weights and measures |

| Conflict zone | Child | Diet therapy | Growth disorder |

| Exposure to violence | Infant | Dietary supplements | Height |

| Fragile states | Young adult | Eating | Human development |

| Migrant | Youth | Feeding behavior | Malabsorption |

| Postconflict | Food | Nutrition assessment | |

| Refugee | Food assistance | Nutrition disorders | |

| Refugee camp | Food quality | Nutritional status | |

| Refugees | Food supply | Starvation | |

| Terrorism | Humanitarian aid | Stunting | |

| Violent conflict | Nutrition service | Wasting | |

| War exposure | Nutrition therapy | Weight | |

| War-torn | Supplements | ||

| Warfare |

These terms were used as index terms where possible or as free-text terms if the database did not have a corresponding index term.

Articles were reviewed and excluded if they did not meet the aforementioned criteria. As discussed above, randomized controlled trials are usually not feasible or ethical when evaluating the effects of nutrition interventions on children’s health status in conflict settings; therefore, cross-sectional or cohort studies were included if a comparison group, baseline measurements, or both were included in the study design.

Studies were included if the intervention contained a nutritional status indicator (i.e., wasting, stunting, or underweight) or other nutrition status indicators (e.g., anemia). Included studies had to measure, with well-defined cutoffs, ≥1 of the following anthropometry-derived nutrition indicators (primary outcomes): wasting (weight-for-height), stunting (height-for-age), underweight (weight-for-age), and the prevalence of moderate acute malnutrition (MAM), SAM, or both. The prevalence of MAM or SAM in the population had to be defined by weight-for-height or height-for-age. MAM and SAM are typically defined between −3 and −2 z scores or <−3 z scores, respectively, in reference to the median child growth standards for wasting or stunting (15, 17, 18). Secondary outcomes in this review included the following: anemia, diarrhea, and mortality. Studies that only included a secondary outcome or outcomes were not included. Studies were included if the primary outcomes of interest were measured by standardized, previously validated methods for growth reference standards, such as indicators used by the National Center for Health Statistics, CDC, or WHO (15, 17, 18). The primary outcomes were selected a priori for this review, consistent with international growth reference standards used internationally to compare the nutritional status of populations and to assess the growth of individual children throughout the world since 1977 (15, 17, 18). Only studies published in English were included, and there was no restriction on publication year.

Data extraction and assessment of methodologic quality.

Two authors (GJC and SDL) independently screened the titles and abstracts of studies identified by the search and applied the prespecified selection criteria to identify relevant studies for full review following a consensus methodology. Relevant information was then independently extracted from each included study into a comprehensive evidence worksheet. Following the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach, predefined criteria were applied to determine the quality of the methodologic rigor of each article, and each article received a quality rating of high, moderate, low, or very low (19).

The GRADE approach was used to rate the quality of evidence for each study, including primary outcome assessment (stunting, wasting, underweight, or recovery from SAM or MAM) (19). Because the majority of the included studies were observational, we paid particular attention to study designs with regard to the application of appropriate eligibility criteria, use of unbiased measurements of exposure and outcome, adequate controls for confounding, and documentation and considerations of differential losses to follow-up across treatment comparison groups (19). The quality of observational studies could be upgraded if studies reported a dose-response gradient, direction of plausible bias, or magnitude of the effect (19).

Results of the search.

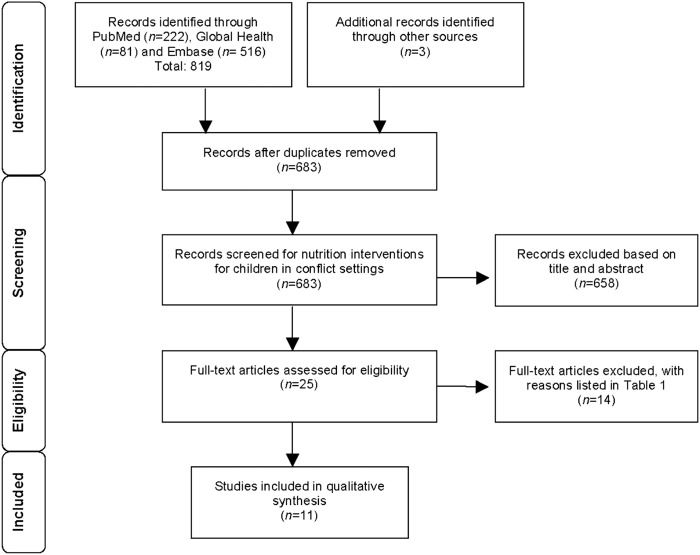

A detailed summary of the search results is shown in Figure 1, which is based on the recommended PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) structure (20). Titles and abstracts from 683 records were screened, of which 25 were assessed in detail to determine eligibility. Of these 25 articles, 11 studies met our eligibility criteria described above. The included articles (n = 11) were published from 1983 to 2012 (21–31). The results from the nutrition interventions for children in conflict settings were difficult to compare across studies due to differences in intervention approaches and outcomes; thus, results are presented by type of intervention in Table 3.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the search strategy.

TABLE 3.

Summary of studies by type of nutritional intervention and primary and secondary outcomes1

| Primary outcomes |

Secondary outcomes |

||||||

| Study, year (ref), quality | Study design, population, sample size (n), age range | Stunting (height-for-age) | Wasting (weight-for-height or MAM/SAM) | Underweight (weight-for-age) | Mortality | Anemia | Diarrhea (2 wk before) |

| TFCs or SFCs | |||||||

| Dzumhur et al., 1995 (21), very low | Cross-sectional (TFC), post–Bosnian War, n = 1283 children, aged 1–14 y | NM | NM | 369 (58.3%) of those underweight (without chronic disease) gained 0.5 kg in weight, placing them >10th percentile (recovered and left program) | NM | NM | NM |

| Nielsen et al., 2004 (22), low | Prospective cohort (SFC), Guinea Bissau post–civil war, n = 247 children, aged 6–59 mo | Prevalence reduced in intervention group but insignificant to comparison group (data not shown) | Median time to recovery: 48 d (95% CI: 34, 72 d) | Prevalence reduced in intervention group but nonsignificant compared with the control group (data not shown) | Reduced mortality of children <5 y of age | NM | NM |

| Rossi et al., 2008 (23), very low | Prospective cohort (TFC/SFC), Burundian refugees, n = 127,420 children, aged 6–59 mo | NM | Small reduction in MAM (8–7%) but increase in SAM (0.5–1.1%) from 2000 to 2004 | NM | Reduction from 6 deaths · 10,000 children−1 · d−1 to 3.1–4.9 deaths · 10,000 children−1 · d−1 (<5 y) | NM | NM |

| Tappis et al., 2012 (24), very low | Retrospective cohort (TFC/SFC); Somali, Sudanese, Ethiopian refugees; n = 42,088 children, aged <5 y | NM | 77.1% recovery from TFCs in 23–43 d, 84.6% recovery from SFCs in 11–20 wk | NM | Mortality rates <1% | NM | NM |

| Taylor, 1983 (25), very low | Cross-sectional (TFC/SFC), Somali refugees, n = 2138 children, aged <5 y | NM | Saba: 46% exceeded discharge level from SFC for weight-for-height | NM. | NM | NM | NM |

| Daray: 60% exceeded discharge level from SFC for weight-for-height; prevalence of malnutrition still high | |||||||

| Vautier et al., 1999 (26), low | Cross-sectional (TFC/SFC); Burundi, Rwandan, Liberian refugees; n = 53,140 children, aged <18 y | NM | Recovered from malnutrition: 76.9%; average time to recovery: 56.6 d | NM | NM | NM | NM |

| MNPs | |||||||

| Bilukha et al., 2011 (27), low | Cross-sectional, Bhutanese refugees, n = 2136 children, aged 6–59 mo | After 7 mo, decrease from 39.2% (34.9–43.7%) to 32.5% (28.4–36.8%)2; after 26 mo, decrease in prevalence of stunting to 23.4% (20.0–27.1%)2 | After 7 mo, increase in prevalence of wasting from 4.2% (2.8–6.4%) to 9.2% (7.0–12.1%)2 | After 7 mo, increase in prevalence from 20.9% (17.5–24.8%) to 28.1% (24.1–32.3%)2 | NM | After 1 y, no change in overall prevalence from baseline of 43.3% (36.3–51.1%) to 43.6% (39.3–48.1%); moderate anemia significantly decreased from 18.9% (15.6–22.7%) to 14.4% (11.7–17.6%) after 3 y | After 1 y, incidence of diarrhea decreased from 30% to 17%2 |

| Rah et al., 2012 (28), low | Cross-sectional; Nepal, Kenya, Bangladesh refugees; n = 19,000 children; aged 6–59 mo | Nepal: decrease from 39% to 23%2 | NM | NM | NM | Nepal: prevalence of moderate anemia decreased (from 19% to 14%) | Nepal: reduction in diarrhea (from 30% to 18%)2 |

| Kenya: decrease in stunting from 12% to 7%2 | Kenya: no change in anemia prevalence in children | Bangladesh: no reduction (20.1% to 19.2%) | |||||

| Bangladesh: values not reported | Bangladesh: anemia prevalence decreased (from 64% to 48%) | Kenya: NM | |||||

| General food assistance programs | |||||||

| Abdeen et al., 2007 (29), low | Cross-sectional, Palestinian refugees, n = 3089 children, aged 6–59 mo | Study population 3.2 percentage points higher than national prevalence, 4.4 percentage points lower than 5 y before intervention | Study population 3.0 percentage points higher than national prevalence | Study population 5.1 percentage points higher than national prevalence | NM | NM | NM |

| Nutrition therapy via outpatient day care centers | |||||||

| Colombatti et al., 2008 (31), very low | Prospective cohort, Guinea Bissau post–civil war, n = 2642 children, aged 1–17 mo | Prevalence of stunting after 19-d intervention: 15% | Prevalence of wasting after 19-d intervention: 21.5% | Prevalence of underweight after 19-d intervention: 23%; overall weight gain from 1% to 25% of initial body weight | No nutrition-related deaths within 1 y (1 death from HIV) | NM | NM |

| Nutrient-dense fortified spread | |||||||

| Lopriore et al., 2004 (30), high | Randomized controlled trial, Saharawi refugees, n = 374 children, aged 3–6 y | Linear growth was 30% faster in intervention group than in control group over entire trial2 | Prevalence reduced in intervention group but nonsignificant compared with the control group (data not shown) | Prevalence reduced in intervention group but nonsignificant compared with the control group (data not shown) | NM | Two-fold increase in hemoglobin concentration in intervention group at 6 mo; anemia was reduced by 90% compared with control | NM |

MAM, moderate acute malnutrition; MNP, micronutrient powder distribution programs; NM, outcome was not measured in the study or not enough information to report; ref, reference; SAM, severe acute malnutrition; SFC, supplementary feeding center; TFC, therapeutic feeding center.

Results were significant (P < 0.05).

Description of studies.

Of the 11 included studies, 6 were cross-sectional studies (21, 25–27, 29, 30), 3 were prospective cohort studies (22, 23, 31), 1 was a retrospective cohort study (24), and 1 was a randomized controlled trial (30). All of the studies included children of both sexes in conflict settings or resettlement or refugee camps. Children were identified as malnourished on the basis of weight-for-height (wasting). Studies used different growth reference standards for the primary variables of interest, such as the National Center for Health Statistics, CDC, or WHO growth reference standards (15, 17, 18); therefore, the classification of children’s nutritional status according to their anthropometric assessment varied among studies. Interventions enrolled children between 1 mo and 18 y of age. Seven studies included children aged ≤5 y. The majority of the studies identified through our systematic review were conducted in regions of Central and East Africa, including the countries of South Sudan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Somalia, and Burundi, most of which are still facing ongoing violent conflicts, primarily due to civil wars among ethnic groups. Overall, 7 of the 11 nutrition intervention studies identified were conducted in postconflict refugee camp settings either within the country or in resettlement areas in neighboring countries (22–24, 28–31).

The overall quality of the evidence was low to very low. Only one study was identified as being of “high” quality (30) because it was a well-executed randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. None of the observational studies were eligible for quality upgrade (20). In fact, 3 were downgraded because the study did not include a comparison or control group or documented differential losses to follow-up (21, 23, 31) and 2 were downgraded for not including a comparison or control group in their study design (25, 27). In the randomized controlled trial (30), the comparison group received a placebo. The intervention groups for observational studies (i.e., cross-sectional or cohort) were compared with children of the same age in different refugee or postconflict populations (24, 26, 28) or with the known national or community prevalence (22, 27, 29).

Results of primary and secondary outcomes specific to type of intervention.

On the basis of our findings, 5 types of interventions emerged, primarily delivered in refugee camp settings. The interventions were delivered exclusive of each other, and the outcomes are reported on the basis of each of the interventions.

Establishment of feeding centers (therapeutic feeding centers and supplementary feeding centers).

Historically, feeding centers have been established by humanitarian aid agencies in response to conflict and emergencies in order to provide immediate nutritional relief (26). In 6 reviewed studies for therapeutic feeding centers (TFCs) and supplementary feeding centers (SFCs) (21–26), it was found that children with SAM were referred to TFCs, which were primarily in-patient feeding centers that provided nutritional food packages and treatment until children recovered from SAM. Food was also provided in the form of weekly rations and packages. Packages typically contained nutrient-rich food products containing powdered milk, biscuits, powdered egg, baby food, corn flour, margarine, and dried mashed potato. For children with MAM, they were referred to SFCs, which are primarily outpatient centers where children collected rations that also included dry supplementary food for home-based nutrition treatment. Interventions delivered via SFCs focus on supplementation by micronutrient tablets and micronutrient-fortified flour mixes, cereal mixes, corn soya blends, oil, and sugar. Overall, TFCs and SFCs helped children experience substantial weight gain to recover from SAM and MAM (21, 24–26). One SFC measured height-for-age but did not find a significant reduction in stunting for children aged 6–59 mo during conflict when compared with the prevalence before conflict. Secondary outcomes included low mortality rates for children <5 y of age (22–24). Diarrhea and anemia outcomes were not assessed in any of the SFC or TFC studies.

Micronutrient powder distribution programs.

Micronutrient powder distribution programs (MNPs) aim to tackle micronutrient deficiencies in children aged <5 y and to improve linear growth to reduce the risk of stunting. Compared with in-patient SFCs and TFCs, micronutrient powders are distributed, typically in refugee camps, to be used at home. Two studies (27, 28) distributed a single-dose sachet containing a combination of multiple vitamins and minerals designed to be mixed in the children’s home-based foods just before consumption (27, 28). Generally, micronutrient powders were well accepted, as shown by high compliance among mothers who also reported the intervention having positive effects on their children’s health, appetite, and energy level (27). The micronutrient powders were associated with significant decreases in the prevalence of stunting among refugee children aged between 5 and 59 mo (27, 28). In one study, there were significant increases in the prevalence of wasting and underweight after 7 mo followed by subsequent improvements in these indicators after 26 mo (27). The authors were unable to fully explain if the increase in stunting and wasting was the result of the intervention (27). For the secondary outcomes, these studies reported reductions in the prevalence of anemia and incidence of diarrhea among refugee children aged between 5 and 59 mo from micronutrient powders (27, 28). Child mortality was not assessed in any of the MNPs.

Food assistance programs.

One intervention involved the distribution of food rations by humanitarian aid agencies during emergencies. This cross-sectional study assessed the nutritional status of children aged 6–59 mo 1 y after the implementation of a food assistance program (29). In a random sample of Palestinian refugees residing in refugee camps, the prevalence of stunting, wasting, and underweight among children aged 6–59 mo was still high when compared with national levels 1 y after the implementation of the food assistance program (29). Overall, the prevalence of malnutrition decreased by 11.4% among children residing in the Gaza Strip refugee camp and by 4.8% among those residing in the West Bank refugee camp (29). The authors noted that calorie and protein intakes were generally lower than recommended for this age group. Mortality, anemia, and diarrhea were not assessed in this study.

Nutrition therapy via outpatient day care center.

One intervention involved establishing a short-term outpatient nutrition center for the treatment of MAM and SAM in children aged 1–17 mo during the rainy season (June–October) in collaboration with a local pediatric clinic postconflict in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa (31). Wasting, stunting, and underweight were assessed in the general outpatient center. Children with MAM were sent home with vitamins and medications for associated infectious diseases. Children with SAM were admitted to a nutritional outpatient unit where they received nutritional and pharmacologic treatments for 8 h, 5 d/wk, until recovery from SAM. To contain the program costs, locally produced food sources were used to treat MAM and SAM. Nutrition therapy included enriched milk and locally prepared porridge and biscuits. Children also received play therapy for emotional needs, and mothers received daily lessons on hygiene, safe water, and infectious disease prevention with the use of graphic tools. Through this intervention, children experienced significant weight gain and recovery from SAM and MAM with no relapse after 1 y (31). Children’s mean length of stay in the nutritional outpatient unit was 19 d (range: 2–23 d) and gained, on average, 4.45 g · kg−1 · d−1 (range: 0.97–8.67 g · kg−1 · d−1), with an overall weight increase ranging from 1% to 25% of their initial body weight (31). Diarrhea and anemia were not assessed in this intervention.

Nutrient-dense fortified spread.

The randomized controlled trial was designed to assess the effect of a highly nutrient-dense spread to reduce anemia and correct linear growth in stunted refugee children aged 3–6 y (30). The intervention group received a fortified spread containing vitamins and minerals, with or without antiparasitic metronidazole treatment, and the control group did not receive any intervention (30). The outcomes were assessed at baseline and at 3 and 6 mo postenrollment (30). Overall, children in the intervention group experienced a reduction in the risk of stunting, wasting, and underweight, and there was a significant reduction in anemia as well (30). Linear growth was significantly greater (20–30%) in the intervention group than in the control group (P < 0.01), with a mean gain of 2.6 ± 0.8 cm after 3 mo in the intervention group compared with 1.9 ± 0.9 cm in the control group. There was no difference in growth between boys and girls in the study groups. Anemia decreased by 90% in the intervention group compared with the control group. Mortality and diarrhea were not assessed in this intervention.

Strengths and limitations of studies.

The majority of studies relied on secondary data analyses of program data instead of being designed to specifically address the research question through primary data collection. Several authors reported a lack of sufficient data available from nutrition program monitoring and surveillance in refugee camps (23, 27–29). There were also challenges with obtaining consistent anthropometric screenings, which questions the reliability of such data. There is a need for better mechanisms to track the adherence of the intervention and coverage in these studies. Without measuring the participants’ adherence and the reach of the program, the impact of these interventions is still in question. Given the nature of implementing immediate aid, conducting interventions and collecting data in emergency settings will continue to pose a significant barrier toward a rigorous scientific evaluation of such interventions. As expected in humanitarian emergency settings, almost all of the studies were observational, introducing methodologic flaws and biases that, in turn, affected the internal validity of the studies. Furthermore, the majority of intervention studies were unable to obtain baseline measurements from the target populations, which is understandable due to the conflict zone context. Some studies did not report between-group significance estimates for primary and secondary outcomes of interest and were only able to report the prevalence. Strengths of the included studies were their large sample sizes (ranging from 374 to 53,140 children), specific details on the type of interventions, and in some instances, documentation of the adherence to the interventions.

Summary of results.

Overall, the identified nutrition interventions were positively associated with the nutrition status of children in conflict settings, including growth. Collectively, studies included in this review indicated that nutrition interventions were helpful in decreasing the risk of stunting, wasting, underweight, infant and child mortality, and anemia or diarrhea or both; however, these results must be interpreted with caution given that the overall quality of the studies was “low” to “very low.”

Discussion

Studies have evaluated nutrition interventions conducted in emergency and refugee camp settings. All of the interventions included in our review reported some success in improving ≥1 of the primary outcomes assessed. Consistent with previous reviews conducted in general emergency settings (12, 13), we found that established nutrition centers, both SFCs and TFCs, were the most common type of intervention and have remained the cornerstone in responding to nutrition needs in conflict zones during emergencies. More than half of the interventions assessed in this study were SFCs and TFCs established in response to emergencies to provide immediate relief. Our results show that these centers have been associated with reducing the occurrence of acute malnutrition and improving weight gain in children.

Strengths and limitations of the review

This narrative review makes an important contribution to the literature, because it is the first, to our knowledge, to assess the types of nutrition interventions to promote the nutrition and growth status in children conducted in conflict or postconflict settings. This review is limited by several factors, and important questions remain with respect to intervention design, adherence, and coverage of the programs. Therefore, improved program evaluation designs are needed to fully understand the potential impact of nutrition interventions during humanitarian emergencies. It is imperative that future studies consistently assess nutritional status indicators, including growth, with the use of the WHO guidelines for measurement of anthropometric (18) and other nutrition outcomes. Studies must also adopt more rigorous methodology by including baseline measurements and appropriate comparison groups to limit confounding and report statistical analyses for all measured outcomes. Research is still needed to better understand the impact of nutrition interventions on children over time in unstable settings. The conclusions drawn from this review are limited by the nature of the studies conducted in emergency settings because most of the studies were observational, and therefore inherently prone to selection bias.

Implications of key findings and next steps

Nutrition interventions may be critical for the well-being and nutritional status of infants, children, and adolescents in conflict and postconflict settings. Given the limited evidence base currently available, it was not possible to reach definitive conclusions with regard to the effect of these interventions on the clinical outcomes of children in conflict settings. Although prospective studies with experimental or quasi-experimental designs would be ideal, there are enormous logistical and ethical constraints with conducting these types of studies in this context. For this reason, observational studies with appropriate comparison groups should be used to improve program data collection. Plausibility statements can be derived from these studies, which, although not randomized, can help in our understanding of the potential impact of the interventions of interest (32). These studies would still need to meet all the ethical principles of research involving highly vulnerable populations—in this instance, refugees or internally displaced individuals escaping or trapped by armed conflicts. We specifically recommend for these studies to focus on MAM or SAM recovery and relapse prevention, long-term growth patterns, child morbidity and mortality, and assessment of adverse health side effects from these interventions, such as diarrhea and allergic reactions. Furthermore, the cost implications should be reported in future studies to enable subsequent cost-effectiveness analysis.

Emergency nutrition programs must follow recent recommendations to expand geographic coverage and access (beyond refugee camps to rural areas) and ensure that aid and nutrition interventions are distributed equitably in all conflict-affected populations (6, 23). Supported by evidence in this review, interventions should be tailored to the social context of areas experiencing conflict (33). Innovative interventions, such as the use of locally sourced food items for nutrition therapy programs and mobilizing local community participation to improve local capacity building and sustainability, will be particularly important in the coming years as funding for humanitarian food aid continues to decrease globally (1). Supplementing nutrition interventions alongside sustainable programs aimed at improving sanitation and hygiene, preventing infectious diseases, and improving access to clean water and health care, including psychological health, are crucial to improve the overall health of children. In addition, providing mothers and caregivers with education on breastfeeding and timely introduction of healthy and nutritious complementary foods is crucial for supporting the health of children aged 0–24 mo (11, 34). The establishment of feeding centers such as TFCs and SFCs should particularly include food safety concerns and the security of individuals commuting to the centers daily amid potentially unsafe and insecure settings (26). Individuals should not be forced to balance the need for food and possible risks to their safety to try to improve their food and nutrition security status under desperate conditions. Providing more options for delivery of weekly take-home nutritional packages and establishing feeding centers in close proximity to affected communities might be effective in the context of unstable settings.

Overall, there is a need for more standardized guidelines for nutrition interventions delivered in conflict settings. This would include having specific guidelines for evaluation, including assessment of anthropometric measures; better surveillance; and consistent strategies documenting intervention adherence and coverage of interventions. Hence, addressing the crucial need to evaluate the success of such programs in conflict settings and their impact in health outcomes is critical for program planning. As government funding and resources to address nutrition in conflict settings continue to decline, accountability and evaluation in the use of limited resources may, in turn, ensure continued funding and supportive policies for humanitarian nutritional aid.

Acknowledgments

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used: MAM, moderate acute malnutrition; MNP, micronutrient powder distribution program; SAM, severe acute malnutrition; SFC, supplementary feeding center; TFC, therapeutic feeding center.

References

- 1.Loewenberg S. Conflicts worsen global hunger crisis. Lancet 2015;386:1719–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Famine Early Warning System Network. Global food security alert: emergency food assistance needs unprecedented as famine threatens four countries [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Mar 15]. Available from: http://www.fews.net/global/alert/january-25–2017.

- 3.UNICEF. Children on the brink: the impact of violence and conflict on Yemen and its children [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/media/files/Yemen_FINAL.PDF.

- 4.UNICEF. The faces of malnutrition [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2017 May 12]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/nutrition/index_faces-of-malnutrition.html.

- 5.UNICEF. In Boko Haram’s wake, a quarter million children severely malnourished [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.unicefusa.org/stories/boko-harams-wake-quarter-million-children-severely-malnourished/30593.

- 6.UNICEF; World Food Program. South Sudan: joint UNICEF/WFP nutrition response plan, progress report [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Nov 1]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/appeals/files/UNICEF_and_WFP_Joint_Nutrition_Response_March_Update.pdf.

- 7.Ghattas H, Sassine AJ, Seyfert K, Nord M, Sahyoun NR. Food insecurity among Iraqi refugees living in Lebanon, 10 years after the invasion of Iraq: data from a household survey. Br J Nutr 2014;112:70–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alajmi F, Somerset SM. Food system sustainability and vulnerability: food acquisition during the military occupation of Kuwait. Public Health Nutr 2015;18:3060–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andersson N, Paredes-Solis S, Legorreta-Soberanis J, Cockcroft A, Sherr L. Breast-feeding in a complex emergency: four linked cross-sectional studies during the Bosnian conflict. Public Health Nutr 2010;13:2097–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prasad AN, Prasad PL. Children in conflict zones. Med J Armed Forces India 2009;65:166–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fander G, Frega M. Responding to nutrition gaps in Jordan in the Syrian refugee crisis: infant and young child feeding education and malnutrition treatment. Field Exchange [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2016 Nov 1]. Available from: http://www.ennonline.net/fex/48/responding.

- 12.Hall A, Blankson B, Shoham J. The impact and effectiveness of emergency nutrition and nutrition related interventions: a review of published evidence 2004-2010. Emergency Nutrition Network [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2017 Mar 1]. Available from: http://www.ennonline.net/impactevidenceemergencynutrition.

- 13.Blanchet K, Sistenich V, Ramesh A, Frison S, Warren E, Smith J, Hossain M, Knight A, Lewis C, Roberts B. An evidence review of research on health interventions in humanitarian crises. Enhancing Learning and Research in Humanitarian Assistance (ELRHA) [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2017 Mar 1]. Available from: http://www.elrha.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/Evidence-Review-22.10.15.pdf.

- 14.de Pee S, Spiegel P, Kraemer K, Wilkinson C, Bilukha O, Seal A, Macias K, Oman A, Fall AB, Yip R, et al. Assessing the impact of micronutrient intervention programs implemented under special circumstances—meeting report. Food Nutr Bull 2011;32:256–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NHANES. CDC growth charts [Internet]. 2000 [cited 2016 Nov 1]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts.

- 16.Ford N, Mills EJ, Zachariah R, Upshur R. Ethics of conducting research in conflict settings. Confl Health 2009;3:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Center for Health Statistics. Growth curves for children birth to 18 years [Internet]. 1977 [cited 2016 Nov 1]. Available from: http://dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a433981.pdf.

- 18.WHO. WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2016 Nov 1]. Available from: http://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/en/.

- 19.WHO. WHO handbook of guideline development. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:W65–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dzumhur Z, Zec S, Buljina A, Terzic R. Therapeutic feeding in Sarajevo during the war. Eur J Clin Nutr 1995;49(Suppl 2):S40–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen J, Valentiner-Branth P, Martins C, Cabral F, Aaby P. Malnourished children and supplementary feeding during the war emergency in Guinea-Bissau in 1998–1999. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:1036–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossi L, Verna D, Villeneuve SL. The humanitarian emergency in Burundi: evaluation of the operational strategy for management of nutritional crisis. Public Health Nutr 2008;11:699–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tappis H, Doocy S, Haskew C, Wilkinson C, Oman A, Spiegel P. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Feeding Program performance in Kenya and Tanzania: a retrospective analysis of routine health information system data. Food Nutr Bull 2012;33:150–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor WR. An evaluation of supplementary feeding in Somali refugee camps. Int J Epidemiol 1983;12:433–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vautier F, Hildebrand K, Dedeurwaeder M, Baquet S, Herp M. Dry supplementary feeding programmes: an effective short-term strategy in food crisis situations. Trop Med Int Health 1999;4:875–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bilukha O, Howard C, Wilkinson C, Bamrah S, Husain F. Effects of multimicronutrient home fortification on anemia and growth in Bhutanese refugee children. Food Nutr Bull 2011;32:264–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rah JH, dePee S, Kraemer K, Steiger G, Bloem M, Spiegel P, Wilkinson C, Bilukha O. Program experience with micronutrient powders and current evidence. J Nutr 2012;142(Suppl):191S–6S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abdeen Z, Greenough PG, Chandran A, Qasrawi R. Assessment of the nutritional status of preschool-age children during the second Intifada in Palestine. Food Nutr Bull 2007;28:274–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lopriore C, Guidoum Y, Briend A, Branca F. Spread fortified with vitamins and minerals induces catch-up growth and eradicates severe anemia in stunted refugee children aged 3–6 y. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:973–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colombatti R, Coin A, Bestagini P, Vieira CS, Schiavon L, Ambrosini V, Bertinato L, Zancan L, Riccardi F. A short-term intervention for the treatment of severe malnutrition in a post-conflict country: results of a survey in Guinea Bissau. Public Health Nutr 2008;11:1357–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Victora CG, Habicht JP, Brye J. Evidence-based public health: moving beyond randomized control trials. Am J Public Health 2004;94:400–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boyden J. Children’s experience of conflict related emergencies: some implications for relief policy and practice. Disasters 1994;18:254–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abdeen Z, Greenough G, Oasrawi R, Dandies B. Nutritional assessment of the West Bank and Gaza Strip [Internet]. Jerusalem (Israel): CARE International; 2003 [cited 2016 Nov 1]. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnada826.pdf.