Abstract

The cytoskeleton underlying cell membranes may influence the dynamic organization of proteins and lipids within the bilayer by immobilizing certain transmembrane (TM) proteins and forming corrals within the membrane. Here we present coarse-grained resolution simulations of a biologically realistic membrane model of asymmetrically organized lipids and TM proteins. We determine the effects of a model of cytoskeletal immobilization of selected membrane proteins using long timescale coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations. By introducing compartments with varying degrees of restraints within the membrane models, we are able to reveal how compartmentalization caused by cytoskeletal immobilization leads to reduced and anomalous diffusional mobility of both proteins and lipids. This in turn results in a reduced rate of protein dimerization within the membrane, and of hopping of membrane proteins between compartments. These simulations provide a molecular realization of hierarchical models often invoked to explain single molecule imaging studies of membrane proteins.

Keywords: Cytoskeleton, Coarse-grained, Molecular dynamics, Diffusion, protein clustering

Introduction

The fluid mosaic model of the cell membrane remains relevant for describing the overall structure of cell membranes 1. However, it is now evident that membrane nano-domains may play important roles in the structure, dynamics, and ultimately functions of cell membranes 2. In addition to the membrane per se, the associated cytoskeletal fence and/or the extracellular matrix structures can strongly influence the diffusion and dynamics of membrane components 3. Compartmentalization of the plasma membrane may result from interactions with the actin-based cytoskeleton via transmembrane (TM) proteins anchored to the membrane skeleton fence 4. Recent estimates in mammalian plasma membranes from combined electron tomography of the membrane cytoskeleton and from lipid diffusional measurements suggests the average compartment sizes may range from ca. 40 to ca. 250 nm depending upon the cell type 5. The formation of ‘picket fence’ structures by cytoskeletally immobilised TM proteins is thought to be the basis of these compartments, and to result in ‘hopping’ diffusion of proteins and lipids in cell membranes, slowing rates of diffusion on longer timescales by a factor of 10-100x relative to those in artificial membranes. However, there are other effects, including crowding, lipid complexity, and lipid-protein interactions, which may influence diffusion within compartments on shorter timescales.

High-resolution optical imaging techniques have revealed the nano-domain clustering of proteins in living cells 6. Furthermore, the plasma membrane is compositionally complex, with an asymmetric distribution of lipids between the inner and outer leaflets 7. It has become increasingly evident that the lipids within the cell membrane not only provide a hydrophobic environment, but also regulate the function and dynamics of various membrane proteins 8–10. Therefore, it is important to account for both the complex distribution of lipid species and for possible corralling effects of cytoskeletally immobilised membrane proteins in order to understand the dynamic behaviour of membranes and their proteins in vivo.

Computational approaches have been used to explore membrane dynamics at a number of levels, ranging from detailed atomistic simulations of lipid bilayers and membrane proteins 11, 12 through coarse-grained (CG) simulations of larger scale membrane assemblies and of protein/membrane interactions 13, 14, to more approximate and/or abstract descriptions of larger (meso) scale membrane behaviour 15, 16. Molecular dynamics simulations and related approaches have been used to explore larger scale dynamic organization of cell membranes, including e.g. membrane curvature regulation by BAR proteins (see e.g. Simunovic et al. 17). Molecular simulations have also been extended to models of cytoskeletal interactions with cell membranes. Recent studies include e.g. a meso-scale CG MD model of red blood cell membranes that includes both the lipid bilayer and the cytoskeleton 18, meso-scale Langevin dynamics simulations of charged lipid (PIP) diffusion in the presence of fencelike barriers 19, and CG MD studies (using MARTINI 20) of sorting of model membrane proteins in the presence of immobilized TM helices 21. CG MD simulations with MARTINI have also been used to explore the effects of immobilized obstacles on the behaviour of lipid nanodomains 22. However, to date it has been difficult to combine near-atomistic detail and biologically realistic membrane models in these studies because of the size complexity challenges of such simulations. A number of recent CG MD simulation studies 13, 14, 23, 24 have explored more realistic models of complex biological membranes.

Here we explore the effect of compartmentalization on the dynamics of proteins and lipids within a compositionally complex plasma membrane model at experimental length scales. Although this problem has been studied in previous computational investigations (see, for example, 21, 22, 25–32), our study is novel in combining a near atomistic (i.e. at the CG level) simulation model with biologically realistic complexity, the latter including asymmetric lipid bilayers and TM domains (from the cytokine receptor gp130 33) on a length scale comparable to that probed in experiments i.e. > 100 nm.

Methods

System Construction

Lipid bilayers were formed from a plasma membrane (PM) model described in detail in previous publications 23, 24. This contained a mixture of the most frequent lipids present in mammalian cell membranes 7, 34, 35, distributed asymmetrically between the inner and outer leaflets, as shown in Fig. 1A. Thus the outer leaflet of the PM contained PC:PE:Sph:GM3:Chol molecules in the ratio 40:10:15:10:25, whilst the inner leaflet of contained PC:PE:PS:PIP2:Chol in the ratio 10:40:15:10:25. PC, PE, and PS were modelled with 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl (i.e. PO) lipid tails. Sph and GM3 were modelled with the ceramide tail with one unsaturated bead. PIP2 was modelled using fully saturated tails. Whilst the fraction of cholesterol present (25%) is at the lower end of the observed levels in mammalian cell membranes 34, 35, we note that e.g. lipidomics studies indicate 25% to 28% cholesterol overall for the cell membranes of MDCK cells, rising to 45% for their apical membranes (which implies <28% in their non-apical membranes) 36, 37.

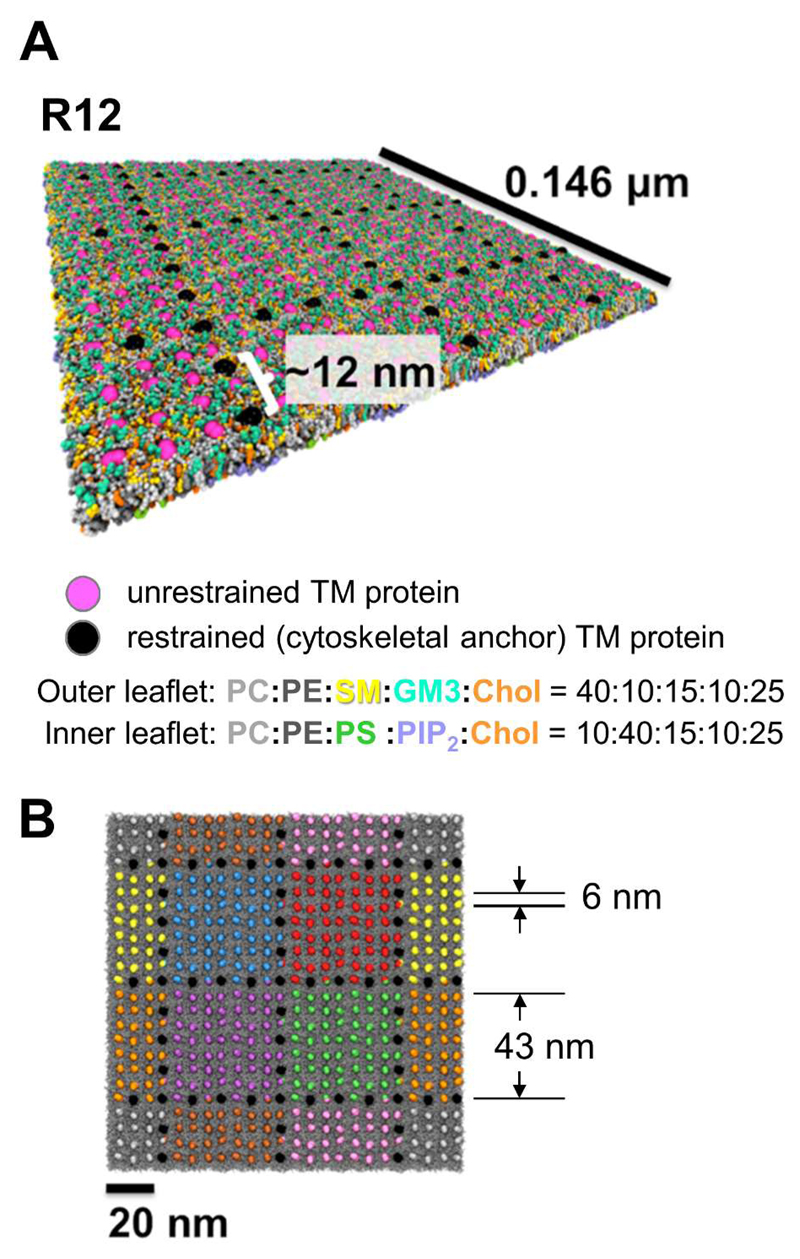

Figure 1.

Overview of a simulation system used to model cytoskeletal compartmentalization of a model cell membrane. (A) The R12 model of a mammalian cell membrane, with lipid composition as given in the main text and shown below in the colour key to the lipid species. Unrestrained transmembrane proteins are in pink, whilst restrained proteins (mimicking membrane proteins anchored to the cytoskeleton) are shown in black. (B) In the initial system configuration (shown for model R12) the proteins are placed on a ~6 nm spaced grid, and the restrained proteins have a linear spacing of ~12 nm and form corrals of dimensions ~43 nm. Here the unrestrained proteins are coloured according to which corral they lie within (see Fig. 2), the restrained proteins are in black, and the lipids in grey.

The transmembrane (TM) domain of gp130 (see SI Fig. S1 for the sequence) was modelled in PyMOL (PyMOL Molecular Graphics System Version 1.5.0.4 Schrödinger, LLC) as previously described 33. To mimic the effect of cytoskeletal interactions forming a picket fence of immobilized TM proteins, we positionally restrained selected TM proteins in grids forming compartments of dimensions approximately 40 nm × 40 nm (Fig. 1). Thus the membrane picket fences were simulated with either a 12 nm (system R12) or a 6 nm (system R6) spacing of the restrained TM proteins (Fig. 1A). A 500 kJ/mol force constant was used in all cases, and the restraints were applied to the backbones beads of two threonine residues in the centre of the membrane-spanning helix. Further details are provided below.

Simulation setup

All simulations were performed using GROMACS 4.6 (www.gromacs.org) 38 with the MARTINI2.2 coarse-grained force field 39, 40. Each simulation system had 576 gp130 TM helices and 63,342 lipids, was solvated using the standard MARTINI water model, along with ions to an approximate concentration of 0.15M NaCl, yielding a total of 2.69 M particles. A 20 fs integration time step was used in all simulations and the temperature was maintained at 323 K using the Berendsen thermostat 41 and the pressure at 1 bar using a Berendsen barostat. The position restrained proteins, the unrestrained proteins, the lipids and the solvent (water and ions) were coupled separately. For both temperature and pressure a coupling constant of 1 ps was used. In all simulations the reaction field coulomb type interaction was used with a switching function from 0.0 to 1.2 nm, and the van der Waals interactions were treated using a cut-off with a switching function from 0.9 to 1.2 nm. The LINCS algorithm was used to constrain bonds to their equilibrium values 42.

Diffusion analysis

Diffusion analysis was performed using previously described 43 open source code (https://github.com/tylerjereddy/diffusion_analysis_MD_simulations) that leverages the MDAnalysis library 44. This utility calculates the mean squared displacement (MSD) of protein molecules or individual lipid species for a range of time windows. For the diffusion analysis of lipids only the head group bead was used and the first 100 ns were excluded to allow for equilibration (i.e., to exclude ballistic motion). For the protein diffusion analysis only the backbone bead of the first residue was used. The calculations were based on data extracted using time windows of 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 ns. The effective anomalous diffusion coefficient (Dα) was obtained by fitting time windows vs. MSD to: MSD = 4DαΔtα, where Δt is the time window and α is the scaling coefficient 45, 46. The scaling coefficient (α) at short (1-10 ns) and long (100 – 500 ns) time window ranges was obtained as the gradient at relevant time window ranges of the log-log scale graph of time windows vs. MSD.

Streamline analysis

Streamline analysis of lipid motion was previously described in detail 47. The trajectory was pre-processed using a smoothing filter of 20 frames on a trajectory containing snapshots at every 4 ns. The streamlines were calculated between two snapshots within the smoothened trajectory using the outer leaflet lipid head groups. In short, the algorithm decomposes any given membrane into a grid and tracks the displacement of lipids between different grid elements, emphasizing collective lipid motions. The full details of the algorithm are available in the open source MDAnalysis.visualization namespace (http://pythonhosted.org/MDAnalysis/documentation_pages/visualization_modules.html).

Protein clustering and kinetics

Protein clustering was determined using MDAnalysis 44 and in house scripts with a 1.5 nm distance cut-off between protein centroids as the threshold to define interactions. The kinetics data was obtained by fitting functions to the clustering data. It was assumed monomer -> dimer -> trimer+tetramers occurs through a consecutive reaction.

The decay of monomers was modelled as a first order decay:

with k1 being the rate constant going from monomer to dimer and [monomer]0=1. The dimer data was fitted using the following equation:

where k2 is the rate constant for the dimer to trimer and tetramer transition.

Calculation of power spectra

The power spectra of the fluctuations in the height of the bilayers was determined as described elsewhere 46. Briefly, the last microsecond of each trajectory was read into python using MDAnalysis 44 and a grid with spacing 0.5 nm defining the surface of each leaflet was created by the cubic interpolation of the positions of phosphate beads of the lipids. The array capturing the local deviation away from planarity is simply the average of these two arrays. This array was transformed into Fourier space using the FFTW routines present in the SciPy 0.14.0 module; 1D power spectra were then created by radial averaging of the 2D spectra. Example code can be obtained from GitHub (https://github.com/philipwfowler/calculate-bilayer-power-spectrum).

Results & Discussion

Simulations

The aim of the simulations was to analyse the effects of picket fence restraint of certain membrane proteins on the dynamics of the lipids and remaining proteins in a simple model of a mammalian PM, compared with simulations free of any picket fence restraints (i.e. with the Free simulation system). In setting up the simulation systems (see above) we have taken into consideration estimates of the size of compartments or corrals in cell membranes. For example, our compartment size of ca. 45 nm (Fig 1B) agrees well with an experimental estimate of between 40 and 46 nm for PtK2 cells 5, and is at the lower end of the range of compartment sizes (from ca. 30 to 300 nm) in different cell types 3, 4. Of course, a cubic grid as the basis of the compartments is a simplification. Cytoskeletal images reveal a complex morphology with shapes ranging from triangular to rectangular to more complex polygons 5. The compartments were thus constructed by positionally restraining selected TM proteins (Fig. 1). Thus, the R6 and R6(xy) simulation systems contained 441 unrestrained proteins along with 135 proteins restrained in xyz (R6) or just in xy (R6(xy)). The R12 system consisted of 513 unrestrained proteins and 63 proteins restrained in xyz. Thus systems R6 and R6(xy) provide respectively an upper and a lower bound on the stiffness of the bilayer along its normal brought about by the coupling of the bilayer properties to the intrinsic stiffness of the cytoskeleton 18, 48. The system without any cytoskeleton present (Free) was published previously 24. The distance between adjacent restrained proteins (6 or 12 nm) is also consistent with current experimental estimates 4.

All of the lipid components of the PM model and > 400 of the gp130 TM spanning protein helices are free to move during the simulations. Thus, by analysing the dynamics of >400 proteins and >63,000 lipids over 10 μs in each simulation, we are able to obtain reasonable statistics on the comparative dynamics of these membrane components.

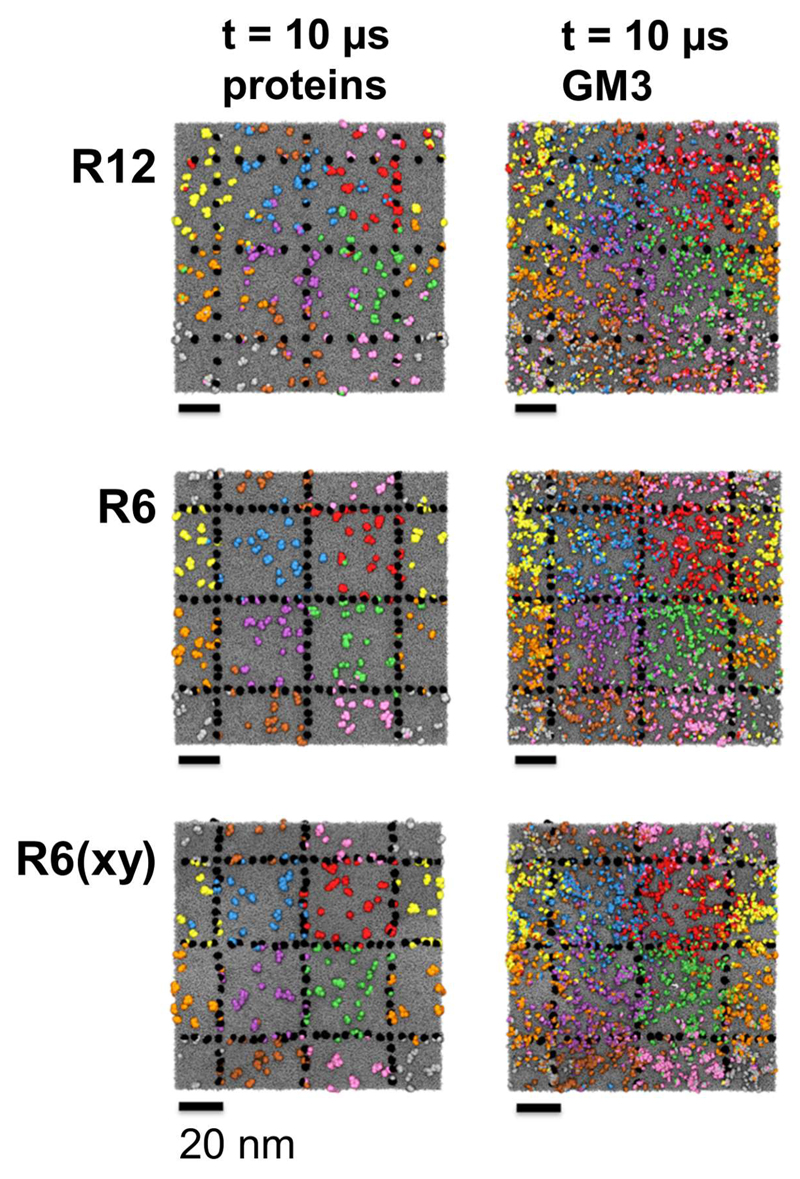

Visual inspection of the three compartmentalized simulations (Fig. 2), compared with the Free control simulation (SI Fig. S2) shows that anchoring of the selected proteins restricts the motions of the remaining proteins and of the lipids to within their initial individual compartments, as judged by e.g. colour coding the TM proteins, and the GM3 glycolipids (the latter within the extracellular leaflet) according to their initial compartments. As expected, movement between compartments was more frequently observed in the R12 system with larger gaps between the ‘picket’ TM proteins, whereas very little redistribution of proteins between the compartments was observed for the R6 system.

Figure 2.

Final (t = 10 μs) snapshots of the R12, R6, and R6(xy) simulations systems with either the proteins or GM3 molecules coloured according to their initial corral (see Fig. 1B). In each case the restrained proteins are shown in black and the lipids in grey.

From visualization of the Free system (SI Fig. S2) it can be seen that 10 μs is sufficient simulation time to allow us to sample motion of both the proteins and the lipids. Thus if one colours the components on their initial positions equivalent to compartments (even though such compartments are not imposed in this control simulation) it can be seen that a significant degree of mixing of GM3 molecules occurred (noting that GM3 is the most slowly diffusing lipid due to its propensity to form nanoclusters – see Koldsø et al. 23 and below). Moreover, many TM proteins have crossed into adjacent ‘compartments’ and a degree of mixing of proteins has also taken place over the course of the 10 μs simulation. Inspection of the R12 simulation system at 10 μs also suggests that the timescale is sufficient to allow us to sample lipid diffusion. For example, if we examine the ‘purple’ GM3 lipids (Fig. 2) at the end of the simulation they have mixed to a clear extent with GM3 molecules from adjacent compartments (i.e. orange, green, and blue).

One can provide a simple measure of the frequency of ‘hopping’ between compartments by counting the number of proteins which have moved out of their initial compartment at the end of a 10 μs simulation. For the R6 and R6(xy) systems, the numbers of hops are 10 and 6 respectively. For R12 the number is much higher at ca. 70. For the control Free system (in which there are no restrained proteins) the number of hops between areas of the membrane equivalent to compartments (SI Fig. S2) is ca. 90. Thus even when the spacing between adjacent pickets is >10 nm (and recalling that the diameter of a single TM helix is ca. 1 nm) there is an observable effect on the frequency of hopping between adjacent compartments on a 10 μs timescale.

Bilayer undulations

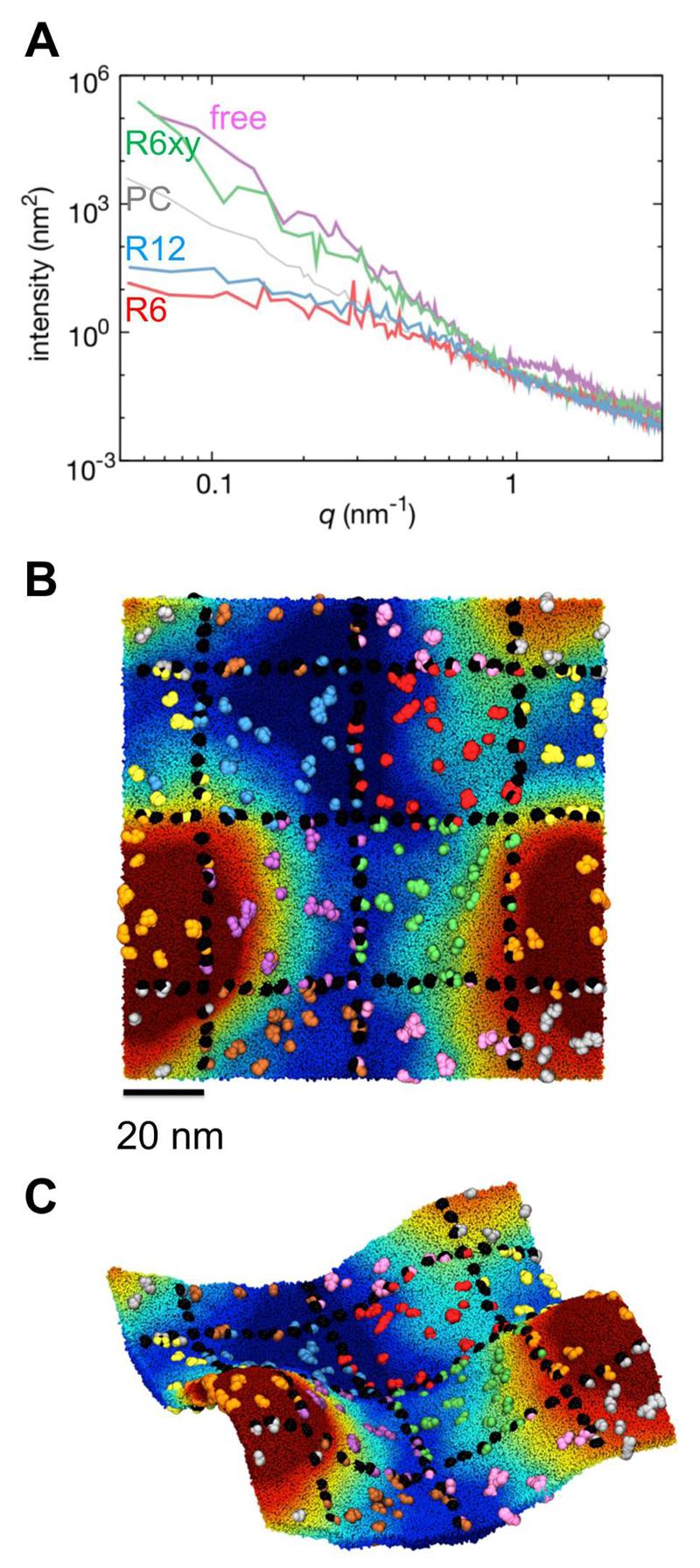

We previously observed undulations (i.e. spontaneous local curvature) in PM simulations (corresponding to the Free system in the current study) on length scales of ca. 10 nm and above 23, 24. Comparable undulations have been seen in both atomistic and coarse-grained simulations of lipid bilayers with simple lipid composition (e.g. single lipid species), albeit of smaller magnitude than those observed in the PM simulations where the undulations seem to be amplified by nanoscale lateral clustering of lipids in the more complex membrane 23. The magnitude of undulations in different simulations may be compared by e.g. calculation of the power spectra of the membrane height fluctuations relative to the bilayer midplane (Fig. 3A) 49.

Figure 3.

(A) Bilayer height fluctuation power spectra, showing the intensity of bilayer height fluctuations as a function of wavenumber (q). The spectra are shown for the R12, R6, and R6(xy) simulation systems, compared with those of a membrane system (free) in which none of the transmembrane proteins was restrained, and (as a control) a simple lipid bilayer (PC) with no proteins present. (B) Top and (C) side view of the R6(xy) system after 10 μs of simulation, showing the development of membrane curvature. Lipid head groups have been coloured according to their z-position relative to the midplane of the bilayer ranging from -12.5 to +12.5 nm (blue to red). Proteins are coloured according to their initial corral (see Fig. 1B and 2) and the restrained (i.e. cytoskeletally anchored) proteins are shown in black.

In those current simulations (i.e. R6 and R12) in which we positionally restrain selected (i.e. cytoskeletally anchored) proteins in both their lateral (xy) coordinates (i.e. projected onto the mean bilayer plane) and in z (along the bilayer normal) the observed undulations are much smaller than in the other systems. Calculation of power spectra of the membrane height fluctuations confirms that the magnitude of the fluctuations is considerably reduced relative both to the Free system (i.e. the unrestrained PM) and to a control PC bilayer, especially at wave numbers of less than q = 0.3 nm-1 (i.e. wavelengths > ca. 3 nm). Thus as might be anticipated, restraining the selected proteins along the perpendicular to the xy plane restrains the membrane as a whole, reflecting the presence of lipid-anchoring charged amino acids at either end of the TM helix which closely couple the bilayer to the spatially restrained helices (SI Fig. S1). Although one might attempt to estimate bending rigidity (Kc) values from the fluctuation power spectra using Helfrich-Canham theory, the latter assumes the membrane is a fluid elastic sheet which therefore is not permitted to be asymmetric, unlike the bilayers in our simulations 49. To explore how membrane curvature and undulations might influence the behaviour of a cytoskeletally restrained membrane, we constructed a system (R6(xy) – see above) in which the selected proteins were only restrained in the xy plane, allowing for vertical (i.e. z) movement of the picket fence. From both the power spectrum from direct visualization (Fig. 3) it is evident that the undulations are of comparable magnitude to those seen in the Free system 24. It is of interest that despite the differences in membrane undulations of R6 and R6(xy) they do not seem to exhibit any substantial differences in the frequency of hopping of unrestrained TM proteins between adjacent compartments (see above).

Diffusion motions of lipids and proteins

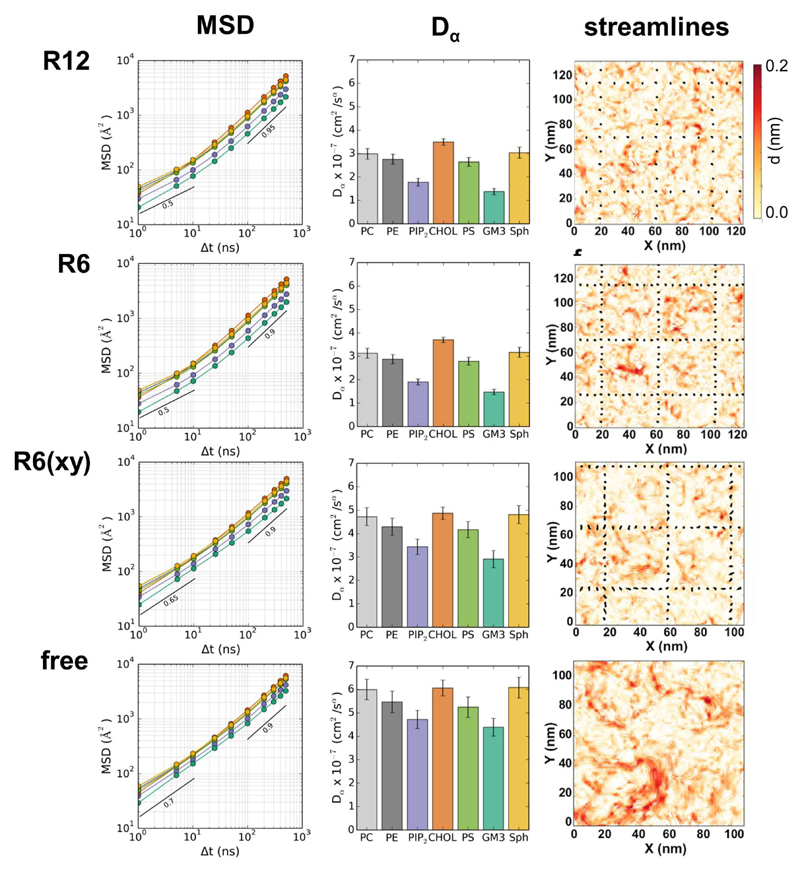

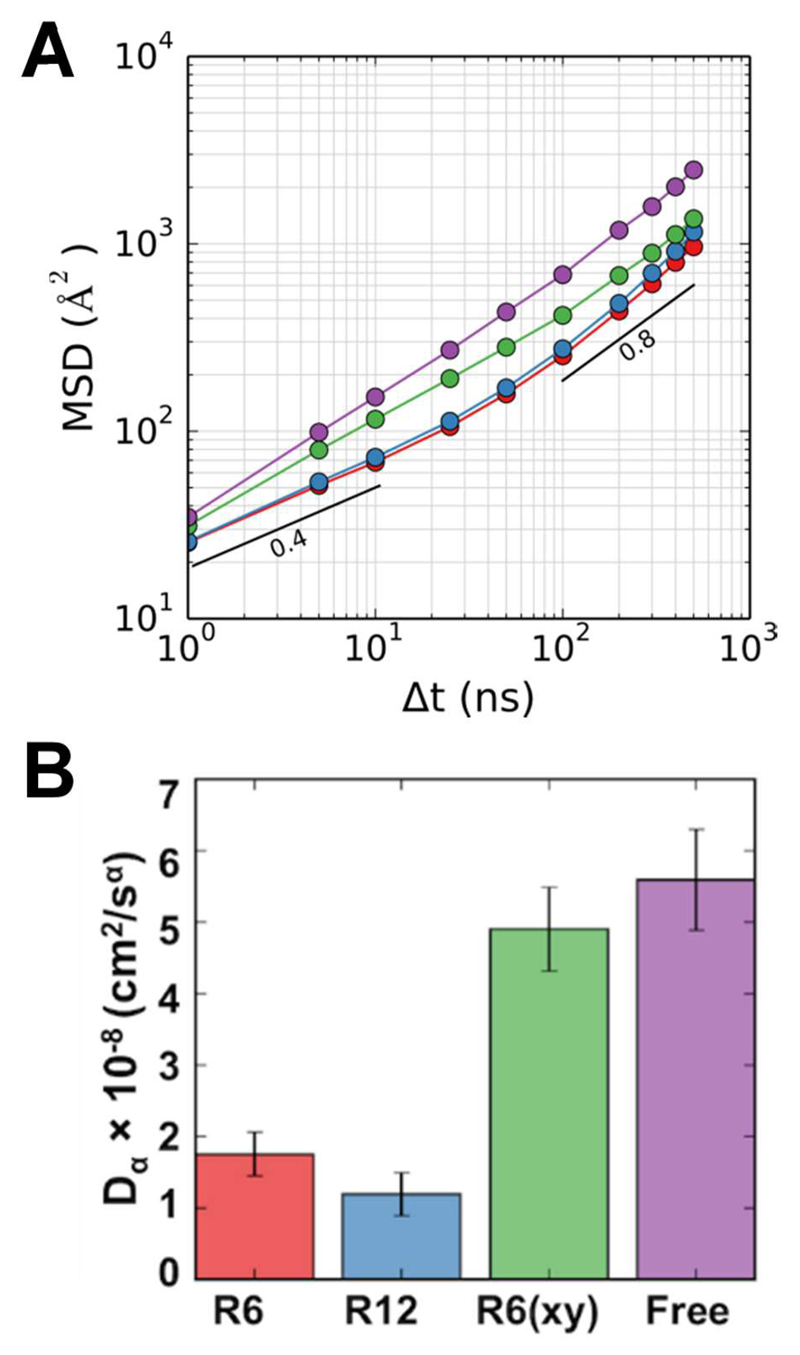

Diffusion coefficients of the proteins and lipids were calculated from their mean square displacement (MSD), fitting a simple anomalous diffusion model (MSD = 4DαΔtα) over the time range 1 to 500 ns (see 50 for a recent general review of anomalous diffusion). Note that that > 60,000 lipid molecules in total and ca. 500 proteins were used to obtain the fits for each simulation. Comparison of the effective lipid diffusion coefficients across the simulations suggests that Dα values were about 2 to 3 times (depending on the lipid) smaller for the R6 and R12 systems than for the Free simulation, with intermediate values for R6(xy). Examination of the MSD vs. time graphs (Fig. 4) suggests that diffusion of lipids is anomalous (α << 1) on short timescales (Δt < 10 ns) and that this is most marked in the compartmentalized systems, especially R6 and R12. Thus we are able to demonstrate a modest reduction in lipid mobility (on the ns to μs timescale) using our model of cytoskeletal anchoring of membrane proteins. Lipid dynamics were also explored using streamlines to visualize the magnitude and direction of local correlated flow movement of lipids within the membranes 47. From this it is evident that movement of the lipids is restricted by the boundaries of the restrained proteins grid, especially within the R6 system (Fig 4). Similar behaviour was observed for the R12 and R6(xy) systems. In contrast, the flow-like movements of the lipids in membranes lacking cytoskeletal anchoring (i.e. the Free system) were relatively unrestricted. Overall, we therefore can demonstrate an effect of compartments on lipid diffusional dynamics (on the sub-μs timescale) but these effects are not large in this complex mixed lipid system. It is interesting to compare with the results of Liang et al. 21 who in a simpler (DPPC:DLiPC:cholesterol) system observed that TM helix immobilization had relatively small effects on diffusion of DLiPC but not on diffusion of DPPC (also on a ns to μs timescale).

Figure 4.

Diffusional mobility of lipids within the four simulation systems showing: (left) mean square displacement (MSD) as a function of time window (Δt) for diffusion of lipids, (center) the effective anomalous diffusion coefficients (Dα) of lipids, and (right) streamline representations 23 of lipid motions. In the MSD and Dα graphs the following color coding is used for the lipids: pale grey = phosphatidyl choline (PC); dark grey = phosphatidyl ethanolamine (PE); purple = PIP2; orange = cholesterol; green = phosphatidyl serine (PS); turquoise = GM3; and yellow = sphingolipid. In the streamline representations the intensity of the color (on a white to red heatmap scale) represents the strength of correlation (the effective speed in a grid region of the bilayer) of local lipid flow.

Analysis of the diffusion of the TM proteins (Fig. 5) revealed a substantive reduction in the diffusion coefficient Dα for both R6 and R12 relative to the Free simulation. This is consistent with the simple measure of inter-compartment hopping of TM proteins described above. It is perhaps puzzling that the R12 membrane shows somewhat slower diffusion (although the difference is small and may not be significant) than does the R6. This suggests that there may be a degree of non-linearity in the relationship between degree of corralling and effects on the diffusional dynamics of the unrestrained proteins.

Figure 5.

Diffusion mobility of proteins within the four simulation systems. (A) Mean square distance (MSD) as a function of duration (Δt) for diffusion of protein. (B) The effective anomalous diffusion coefficients of proteins within all four systems. In both graphs the color coding is: blue = R12; red = R6; green = R6(xy); and purple = Free. Error bars in B show standard deviations calculated from the non-linear parameter fits.

However, the value of Dα for R6(xy) is not substantially reduced relative to the Free system, despite a low rate of hopping (comparable to that of R6). It is of interest that the diffusion of proteins was observed to be faster in R6(xy), the membrane of which was undergoing dynamic undulations (see above), even if one allows for a maximum factor of 2 which may arise from the approximation of calculating an effective diffusion coefficient in a ruffled membrane compared to a flat one 51. It is also of interest that the degree of anomalous diffusion of the TM proteins in the shorter time regime (i.e. ≤ 10 ns) is more marked for the R6 and R12 systems, as indicated by exponents of ca. α = 0.45 (see Table 1). Together these results indicate that not only do the restrained TM protein ‘pickets’ reduce longer timescale protein migration between compartments, but that they result in slower and more anomalous diffusion of proteins (and also lipids – see Table 1) on the shorter (10 ns) timescale. The latter is consistent with e.g. the hierarchical picture of cell membrane dynamic organization described by Kusumi et al. 4.

Table 1. Anomalous Diffusion of Lipids and Proteins.

| Simulation | Component | α1-10 ns | α100-500 ns |

|---|---|---|---|

| R12 | lipid | 0.53 | 0.96 |

| protein | 0.45 | 0.89 | |

| R6 | lipid | 0.52 | 0.95 |

| protein | 0.43 | 0.83 | |

| R6(xy) | lipid | 0.59 | 0.88 |

| protein | 0.57 | 0.73 | |

| Free | lipid | 0.64 | 0.88 |

| protein | 0.64 | 0.79 |

Protein clustering

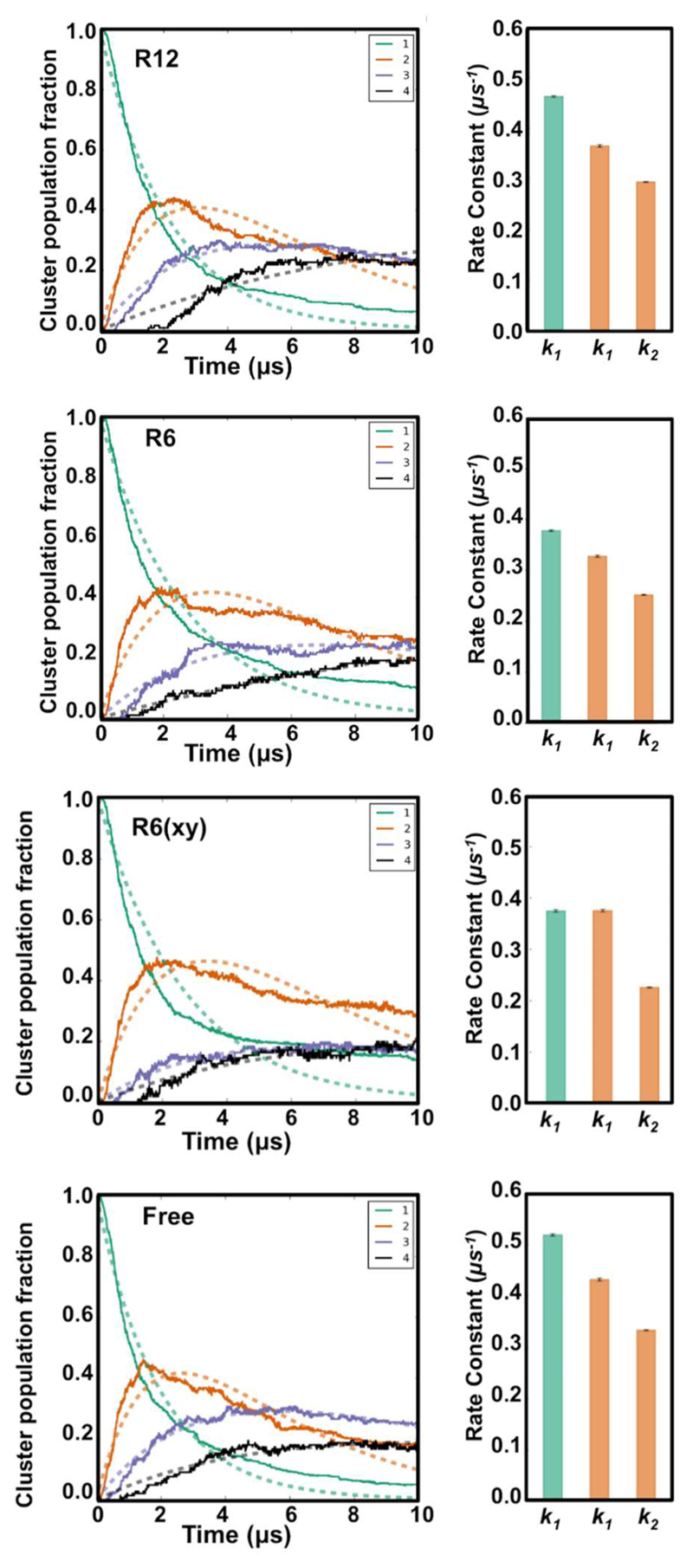

The gp130 TM protein utilized in this study has previously been observed to form oligomers when multiple copies are present 23, 24. Comparable behaviour has been observed for other TM proteins using a range of computational approaches (see e.g. 52–54). We therefore wanted to determine the extent to which compartmentalization within the cell membrane would influence the formation of TM protein clusters. To this end we calculated the cluster distribution over time as previously described 24, and estimated a rate constants for TM domain monomer to dimer (k1) and dimer to trimer/tetramer (k2) transitions (see Methods above). A clear effect of compartmentalization on the rates of oligomerization was seen, relative to the Free simulation, which was most pronounced for the R6 and R6(xy) simulations (Fig. 6). The R12 rates were intermediate between those for R6 and Free. Interestingly the rates of oligomerization were significantly lower for R6(xy), even though (see above) the effective protein diffusion coefficients in this simulation were not much reduced compared to those for the Free simulation. Both the monomer to dimer, and the dimer to trimer rate constants were reduced by compartmentalization

Figure 6.

Protein clustering within the four simulation systems. (A) The kinetics of TM protein clustering over time (solid lines) and the corresponding fits (dotted lines, see main text for details). Each graph shows the fraction of protein monomers (green), dimers (orange), trimers (purple) and tetramers (black). (B) Rate constants for transitions from monomer to dimer (k1) and dimer to trimer (k2). Two values are shown in each panel for k1, namely the value extracted from the first order decay of the fraction of monomer (in green), and the values of k1 (for dimer accumulation) and k2 (for dimer to trimer transition) as estimated by fitting to the dimer curve shown in orange (See SI for details).

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that it is now possible to undertake simulations of a biologically realistic PM membrane, with inclusion of a model of compartmentalization which mimics cytoskeletal anchoring of a subset of membrane proteins. Our current model remains an approximation of in vivo cell membranes, both in terms of the geometrical arrangement of the anchors and of the relative simplicity of the proteins included. However, it provides insights which are likely transferable to yet more complex systems. In particular, anchoring (of between 11 and 23% of TM domains) can be seen to impede ‘hopping’ between adjacent compartments of unrestrained TM domains. The anchored TM domains can modulate the undulations of the bilayer as a whole. Two cases (R6 and R6(xy)) provide upper and lower bounds of the possible degree of (cytoskeletal) anchoring perpendicular to the lipid bilayer. It is evident that even anchors formed by single TM helices are able to couple the mechanical properties of the bilayer to that of the underlying cytoskeleton. Small but significant effects of compartmentalization on diffusion of lipids and TM proteins are seen, both in terms of an overall slowing of diffusion and also effects of the extent of anomalous diffusion. These include ‘corralling’ of lipid flows, and effects on lipid and on protein diffusion observed on a ns to μs timescale. It is interesting to reflect how these may be related to experimental observations, which are generally on a longer timescale e.g. ms for STED-FCS of fluorescently labelled lipids 55. (This is discussed in a more detail below.) Alongside the effects on diffusion, there are also small but significant effects on the oligomerisation of the unrestrained TM protein domains. The coupling between TM domain immobilization, slowing and corralling of lipids, and of consequent effects on protein oligomerization might be anticipated to have effects on protein signalling mechanisms which may involve e.g. clustering of receptor TM domains 56, 57.

It is useful to reflect on the possible limitations of our model. The MARTINI model is clearly an approximation compared to full atomistic simulations. For example, the simplified representation of the sphingolipid headgroup in MARTINI may result in too high a rate of diffusion of this species. However, by direct comparison with large scale atomistic simulations it has been shown to reproduce reasonably well a number of dynamic properties of lipid bilayers, including large scale undulations 49 and overall lipid diffusion behaviour 46. In terms of lipid/protein interactions, simulations using the MARTINI forcefield have been shown to reproduce structurally verified lipid binding sites (e.g. 58–60, and more recently to yield estimates of lipid/protein interaction free energy landscapes which are consistent with lipid specificity and effects of mutations on such interactions 60–62. Furthermore, for simple systems (e.g. the glycophorin TM domain) the strength of protein-protein interactions in MARTINI 63, 64 and atomistic 65, 66 are broadly comparable. The other major limitation is restricting our protein model to a single species of (simple) TM domains. Indeed, it will be of interest to extend such studies to consideration of more complex TM proteins (e.g. receptors and channels 67) which exhibit specific interactions with lipids including glycolipids, cholesterol, and PIP2. It will also be important to complement the current simulations by equivalent atomistic simulations (which will be somewhat computationally challenging) so as to more accurately capture e.g. the behaviour of ordered-domain-forming lipids (i.e. sphingolipid and cholesterol) than is possible with the MARTINI model.

The picture emerging from our simulations, in which the restrained ‘picket’ proteins influence the dynamics of protein and lipids on two timescales, agrees well with the hierarchcical concept of cell membrane dynamics described by e.g. Kusumi et al 4. It also aids interpretation of more recent data on spatiotemporal heterogenity of lipids in living cells 55, and on transbilayer lipid interactions and nanoclustering of lipid-anchored proteins 68.

Overall, our observations indicate the importance of considering interactions with the underlying cytoskeleton in order to fully understand the complex dynamic behavior of membrane proteins and lipids in vivo. Having demonstrated that such interactions may be included in biologically realistic models of cell membranes, it should now be possible to extend such simulation studies to explore e.g. hopping of diverse proteins mechanisms between bigger and more complex compartments generated by more biologically realistic cytoskeletal restraints on transmembrane proteins. Furthermore, protein crowding alters the nature of anomalous diffusion of lipids and proteins within membranes 53, 69 as a consequence of correlative motions. It will be of interest in the future to study the combined effects of both cytoskeletal immobilisation of membrane proteins and of protein crowding in cell membranes.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Acknowledgments

Research in M.S.P.S’s group is funded by grants from ESPRC, BBSRC, the Edward Penley Abraham Cephalosporin Fund., and the Wellcome Trust (092970/Z/10/Z). H.K. acknowledges a research fellowship from the Alfred Benzon Foundation. T.R. acknowledges postdoctoral funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and support from Somerville College, Oxford. PRACE is acknowledged for computer time. Philip Maini and Eamonn Gaffney are acknowledged for valuable discussions, and especially to Matthieu Chavent for the streamline visualization.

References

- (1).Nicolson GL. The fluid-mosaic model of membrane structure: still relevant to understanding the structure, function and dynamics of biological membranes after more than 40 years. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomemb. 2014;1838:1451–1466. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Sezgin E, Davis SJ, Eggeling C. Membrane nanoclusters-tails of the unexpected. Cell. 2015;161:433–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Ritchie K, Iino R, Fujiwara T, Murase K, Kusumi A. The fence and picket structure of the plasma membrane of live cells as revealed by single molecule techniques (Review) Molec Memb Biol. 2003;20:13–18. doi: 10.1080/0968768021000055698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Kusumi A, Suzuki KGN, Kasai RS, Ritchie K, Fujiwara TK. Hierarchical mesoscale domain organization of the plasma membrane. Trends Biochem Sci. 2011;36:604–615. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Fujiwara TK, Iwasawa K, Kalay Z, Tsunoyama TA, Watanabe Y, Umemura YM, Murakoshi H, Suzuki KGN, Nemoto YL, Morone N, Kusumi A. Confined diffusion of transmembrane proteins and lipids induced by the same actin meshwork lining the plasma membrane. Molec Biol Cell. 2016;27:1101–1119. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-04-0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Saka SK, Honigmann A, Eggeling C, Hell SW, Lang T, Rizzoli SO. Multi-protein assemblies underlie the mesoscale organization of the plasma membrane. Nature Comms. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Coskun Ü, Simons K. Cell membranes: the lipid perspective. Structure. 2011:1543–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Coskun Ü, Grzybek M, Drechsel D, Simons K. Regulation of human EGF receptor by lipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:9044–9048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105666108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Zocher M, Zhang C, Rasmussen SGF, Kobilka BK, Muller DJ. Cholesterol increases kinetic, energetic, and mechanical stability of the human beta(2)-adrenergic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E3463–E3472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210373109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Drachmann ND, Olesen C, Moller JV, Guo Z, Nissen P, Bublitz M. Comparing crystal structures of Ca2+-ATPase in the presence of different lipids. Febs Journal. 2014;281:4249–4262. doi: 10.1111/febs.12957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Javanainen M, Hammaren H, Monticelli L, Jeon J-H, Miettinen MS, Martinez-Seara H, Metzler R, Vattulainen I. Anomalous and normal diffusion of proteins and lipids in crowded lipid membranes. Faraday Disc. 2013;161:397–417. doi: 10.1039/c2fd20085f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Poyry S, Cramariuc O, Postila PA, Kaszuba K, Sarewicz M, Osyczka A, Vattulainen I, Rog T. Atomistic simulations indicate cardiolipin to have an integral role in the structure of the cytochrome bc(1) complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1827:769–778. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Ingolfsson HI, Melo MN, van Eerden FJ, Arnarez C, Lopez CA, Wassenaar TA, Periole X, de Vries AH, Tieleman DP, Marrink SJ. Lipid organization of the plasma membrane. J Amer Chem Soc. 2014;136:14554–14559. doi: 10.1021/ja507832e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Ingolfsson HI, Arnarez C, Periole X, Marrink SJ. Computational ‘microscopy’ of cellular membranes. J Cell Sci. 2016 doi: 10.1242/jcs.176040. (online) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Reynwar BJ, Illya G, VA M, Müller MM, Kremer K, Deserno M. Aggregation and vesiculation of membrane proteins by curvature-mediated interactions. Nature. 2007;447:461–464. doi: 10.1038/nature05840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lee CK, Pao CW, Smit B. PSII-LHCII Supercomplex Organizations in Photosynthetic Membrane by Coarse-Grained Simulation. J Phys Chem B. 2015;119:3999–4008. doi: 10.1021/jp511277c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Simunovic M, Voth GA. Membrane tension controls the assembly of curvature-generating proteins. Nature Comms. 2015;6 doi: 10.1038/ncomms8219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Li H, Lykotrafitis G. Erythrocyte membrane model with explicit description of the lipid bilayer and the spectrin network. Biophys J. 2014;107:642–653. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Lee KI, Im W, Pastor RW. Langevin dynamics simulations of charged model phosphatidylinositol lipids in the presence of diffusion barriers: toward an atomic level understanding of corralling of PIP2 by protein fences in biological membranes. BMC Biophysics. 2014;7 doi: 10.1186/s13628-014-0013-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Marrink SJ, Tieleman DP. Perspective on the Martini model. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:6801–6822. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60093a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Liang Q, Wu QY, Wang ZY. Effect of hydrophobic mismatch on domain formation and peptide sorting in the multicomponent lipid bilayers in the presence of immobilized peptides. J Chem Phys. 2014;141 doi: 10.1063/1.4891931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Fischer T, Risselada HJ, Vink RLC. Membrane lateral structure: the influence of immobilized particles on domain size. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2012;14 doi: 10.1039/c2cp41417a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Koldsø H, Shorthouse D, Hélie J, Sansom MSP. Lipid clustering correlates with membrane curvature as revealed by molecular simulations of complex lipid bilayers. PLoS Comp Biol. 2014;10:e1003911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Koldsø H, Sansom MSP. Organization and dynamics of receptor proteins in a plasma membrane. J Amer Chem Soc. 2015;137:14694–14704. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Leitner DM, Brown FLH, Wilson KR. Regulation of protein mobility in cell membranes: a dynamic corral model. Biophys J. 2000;78:125–135. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76579-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Brown FLH, Leitner DM, McCammon JA, Wilson KR. Lateral diffusion of membrane proteins in the presence of static and dynamic corrals: Suggestions for appropriate observables. Biophys J. 2000;78:2257–2269. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76772-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Brown FLH. Regulation of protein mobility via thermal membrane undulations. Biophys J. 2003;84:842–853. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74903-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Sung BJ, Yethiraj A. Lateral diffusion of proteins in the plasma membrane: spatial tessellation and percolation theory. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:143–149. doi: 10.1021/jp0772068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Sung BJ, Yethiraj A. Computer simulations of protein diffusion in compartmentalized cell membranes. Biophys J. 2009;97:472–479. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.04.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Li H, Lykotrafitis G. Two-component coarse-grained molecular-dynamics model for the human erythrocyte membrane. Biophys J. 2012;102:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.11.4012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Kalay Z, Fujiwara TK, Otaka A, Kusumi A. Lateral diffusion in a discrete fluid membrane with immobile particles. Physi Rev E. 2014;89 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.89.022724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Li H, Lykotrafitis G. Vesiculation of healthy and defective red blood cells. Physical Review E. 2015;92 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.92.012715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Koldsø H, Sansom MSP. Local lipid reorganization by a transmembrane protein domain. J Phys Chem Lett. 2012;3:3498–3502. doi: 10.1021/jz301570w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).van Meer G, Voelker DR, Feigenson GW. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).van Meer G, de Kroon AIPM. Lipid map of the mammalian cell. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:5–8. doi: 10.1242/jcs.071233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Sampaio JL, Gerl MJ, Klose C, Ejsing CS, Beug H, Simons K, Shevchenko A. Membrane lipidome of an epithelial cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:1903–1907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019267108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Gerl MJ, Sampaio JL, Urban S, Kalvodova L, Verbavatz JM, Binnington B, Lindemann D, Lingwood CA, Shevchenko A, Schroeder C, Simons K. Quantitative analysis of the lipidomes of the influenza virus envelope and MDCK cell apical membrane. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:213–221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Hess B, Kutzner C, van der Spoel D, Lindahl E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J Chem Theor Comp. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Marrink SJ, Risselada J, Yefimov S, Tieleman DP, de Vries AH. The MARTINI force field: coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:7812–7824. doi: 10.1021/jp071097f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Monticelli L, Kandasamy SK, Periole X, Larson RG, Tieleman DP, Marrink SJ. The MARTINI coarse grained force field: extension to proteins. J Chem Theor Comp. 2008;4:819–834. doi: 10.1021/ct700324x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, van Gunsteren WF, DiNola A, Haak JR. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J Chem Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Hess B, Bekker H, Berendsen HJC, Fraaije JGEM. LINCS: A linear constraint solver for molecular simulations. J Comp Chem. 1997;18:1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Reddy T, Shorthouse D, Parton DL, Jefferys E, Fowler PW, Chavent M, Baaden M, Sansom MS. Nothing to sneeze at: a dynamic and integrative computational model of an influenza A virion. Structure. 2015;23:584–597. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Michaud-Agrawal N, Denning EJ, Woolf TB, Beckstein O. MDAnalysis: a toolkit for the analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. J Comput Chem. 2011;32:2319–2327. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Kneller GR, Baczynski K, Pasenkiewicz-Gierula M. Communication: Consistent picture of lateral subdiffusion in lipid bilayers: Molecular dynamics simulation and exact results. Journal of Chemical Physics. 2011;135 doi: 10.1063/1.3651800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Stachura S, Kneller GR. Anomalous lateral diffusion in lipid bilayers observed by molecular dynamics simulations with atomistic and coarse-grained force fields. Molec Simul. 2014;40:245–250. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Chavent M, Reddy T, Goose J, Dahl ACE, Stone JE, Jobard B, Sansom MSP. Methodologies for the analysis of instantaneous lipid diffusion in MD simulations of large membrane systems. Faraday Disc. 2014;169:455–475. doi: 10.1039/c3fd00145h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Popescu G, Ikeda T, Goda K, Best-Popescu CA, Laposata M, Manley S, Dasari RR, Badizadegan K, Feld MS. Optical measurement of cell membrane tension. Physical Review Letters. 2006;97 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.97.218101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Fowler PF, Chavent M, Duncan A, Helie J, Koldsø H, Sansom MSP. Membrane stiffness is modified by integral membrane proteins. Soft Matter. 2016 doi: 10.1039/c6sm01186a. (submitted) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Metzler R, Jeon J-H, Cherstvy AG, Barkai E. Anomalous diffusion models and their properties: non-stationarity, non-ergodicity, and ageing at the centenary of single particle tracking. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2014;16:24128–24164. doi: 10.1039/c4cp03465a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Naji A, Brown FLH. Diffusion on ruffled membrane surfaces. J Chem Phys. 2007;126:235103. doi: 10.1063/1.2739526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Periole X, Huber T, Marrink SJ, Sakmar TP. G protein-coupled receptors self-assemble in dynamics simulations of model bilayers. J Amer Chem Soc. 2007;129:10126–10132. doi: 10.1021/ja0706246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Goose JE, Sansom MSP. Reduced lateral mobility of lipids and proteins in crowded membranes. PLoS Comp Biol. 2013;9:e1003033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Benjamini A, Smit B. Lipid mediated packing of transmembrane helices - a dissipative particle dynamics study. Soft Matter. 2013;9:2673–2683. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Honigmann A, Mueller V, Ta H, Schoenle A, Sezgin E, Hell SW, Eggeling C. Scanning STED-FCS reveals spatiotemporal heterogeneity of lipid interaction in the plasma membrane of living cells. Nature Comms. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms6412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Salaita K, Nair PM, Petit RS, Neve RM, Das D, Gray JW, Groves JT. Restriction of receptor movement alters cellular response: physical force sensing by EphA2. Science. 2010;327:1380–1385. doi: 10.1126/science.1181729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Xu Q, Lin WC, Petit RS, Groves JT. EphA2 Receptor Activation by Monomeric Ephrin-A1 on Supported Membranes. Biophys J. 2011;101:2731–2739. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.10.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Schmidt MR, Stansfeld PJ, Tucker SJ, Sansom MSP. Simulation-based prediction of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate binding to an ion channel. Biochem. 2013;52:279–281. doi: 10.1021/bi301350s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Stansfeld PJ, Goose JE, Caffrey M, Carpenter EP, Parker JL, Newstead N, Sansom MSP. MemProtMD: automated insertion of membrane protein structures into explicit lipid membranes. Structure. 2015;23:1350–1361. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2015.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Arnarez C, Mazat J-P, Elezgaray J, Marrink S-J, Periole X. Evidence for cardiolipin binding sites on the membrane-exposed surface of the cytochrome bc1. J Amer Chem Soc. 2013;135:3112–3120. doi: 10.1021/ja310577u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Naughton FB, Kalli AC, Sansom MSP. Association of peripheral membrane proteins with membranes: Free energy of binding of GRP1 PH domain with PIP-containing model bilayers. J Phys Chem Lett. 2016;7:1219–1224. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpclett.6b00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Hedger G, Koldsø H, Sansom MSP. Free energy landscape of lipid interactions with regulatory binding sites on the transmembrane domain of the EGF receptor. J Phys Chem B. 2016 doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.6b01387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Sengupta D, Marrink SJ. Lipid-mediated interactions tune the association of glycophorin A helix and its disruptive mutants in membranes. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2010;12:12987–12996. doi: 10.1039/c0cp00101e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Janosi L, Prakash A, Doxastakis M. Lipid-modulated sequence-specific association of glycophorin A in membranes. Biophys J. 2010;99:284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Hénin J, Pohorille A, Chipot C. Insights into the recognition and association of transmembrane α-helices. The free energy of α-helix dimerization in glycophorin A. J Amer Chem Soc. 2005;127:8478–8484. doi: 10.1021/ja050581y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Kuznetsov AS, Polyansky AA, Fleck M, Volynsky PE, Efremov RG. Adaptable lipid matrix promotes protein-protein association in membranes. J Chem Theor Comput. 2015;11:4415–4426. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Hedger G, Sansom MSP. Lipid interaction sites on channels, transporters and receptors: recent insights from molecular dynamics simulations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2016.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Raghupathy R, Anilkumar AA, Polley A, Singh PP, Yadav M, Johnson C, Suryawanshi S, Saikam V, Sawant SD, Panda A, Guo Z, et al. Transbilayer Lipid Interactions Mediate Nanoclustering of Lipid-Anchored Proteins. Cell. 2015;161:581–594. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Jeon JH, Javanainen M, Martinez-Seara H, Metzler R, Vattulainen I. Protein crowding in lipid bilayers gives rise to non-Gaussian anomalous lateral diffusion of phospholipids and proteins. Phys Rev X. 2016;6:021006. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.