Abstract

Objective

Assess quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) presenting with neuropsychiatric symptoms (neuropsychiatric SLE, NPSLE).

Methods

Quality of life was assessed using the Short-Form 36 item Health Survey (SF-36) in patients visiting the Leiden NPSLE clinic at baseline and at follow-up. SF-36 subscales and summary scores were calculated and compared with quality of life of the general Dutch population and patients with other chronic diseases.

Results

At baseline, quality of life was assessed in 248 SLE patients, of whom 98 had NPSLE (39.7%). Follow-up data were available for 104 patients (42%), of whom 64 had NPSLE (61.5%). SLE patients presenting neuropsychiatric symptoms showed a significantly reduced quality of life in all subscales of the SF-36. Quality of life at follow-up showed a significant improvement in physical functioning role (p = 0.001), social functioning (p = 0.007), vitality (p = 0.023), mental health (p = 0.014) and mental component score (p = 0.042) in patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms not attributed to SLE, but no significant improvement was seen in patients with NPSLE.

Conclusion

Quality of life is significantly reduced in patients with SLE presenting neuropsychiatric symptoms compared with the general population and patients with other chronic diseases. Quality of life remains considerably impaired at follow-up. Our results illustrate the need for biopsychosocial care in patients with SLE and neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Keywords: SLE, NPSLE, neuropsychiatric symptoms, SF-36, quality of life

Introduction

In the last decades, quality of life (QoL) research has emerged as a crucial component of medical care for assessing the impact of illness on patients and the value of medical interventions. QoL is defined as ‘the functional effect of an illness and its consequent therapy upon a patient, as perceived by the patient’.1 QoL assessment has clinical implications by demonstrating the need for incorporating patients’ perceptions into therapeutic approaches and supportive care.

Assessment in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) has demonstrated a significantly reduced QoL in comparison with the general population.2 Moreover, QoL seems to be significantly more impaired than in other chronic diseases and affects all health domains at an earlier age.3 Studies have shown improvement of QoL over time in patients with early SLE, most likely because patients suffered from active disease and improved after receiving appropriate therapy. On the other hand, longer disease duration has not been associated with an improvement of QoL at follow-up.4,5

QoL has also been analysed in specific subsets of patients with SLE, including those presenting neuropsychiatric symptoms.6–10 Neuropsychiatric symptoms are common in SLE patients, but can only be directly attributed to this disease in one-third of the cases (neuropsychiatric SLE, NPSLE).11,12 Factors that might be involved in the other cases include the social burden of the disease and organ damage caused by the disease or treatment.11,13 Hanly et al. have demonstrated in several studies that neuropsychiatric events presenting in SLE, independently of their aetiology (SLE or non-SLE related), have a marked negative impact on QoL.6–10 In addition, they demonstrated that SLE-related neuropsychiatric events improve or resolve more frequently than non-SLE related events, especially early in the disease.6 The authors suggested that a therapeutic window of opportunity to treat pathogenic mediators with (immunosuppressive) therapy may exist, implying that early disease detection and treatment could improve QoL.6 However, knowledge about changes over time of QoL of SLE patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms remains scarce. Two prospective analyses have shown a decrease in mental component scores over time, whereas the results on the physical component scores are inconclusive.6,10

Previous studies have shown that the Short-Form 36 item Health Survey (SF-36), a tool for measuring health-related QoL, is a valid and reliable tool for identifying the effect of SLE on physical, mental and social domains of QoL.14 It is a widely used generic questionnaire in QoL-research because of its excellent psychometric characteristics. The SF-36 has also been validated for NPSLE patients. Hanly et al. demonstrated that changes in SF-36 summary and subscale scores are strongly associated with the clinical outcome of neuropsychiatric events in SLE patients.15

Our aim is (a) to analyse the QoL using the SF-36 in patients with SLE presenting with neuropsychiatric symptoms in a prospective cohort, (b) to compare our results with the general (Dutch) population and (Dutch) patients with other chronic diseases, including migraine, mood disorder, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and lupus nephritis and (c) to assess the evolution of QoL over time between baseline and follow-up of these patients with SLE and neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Methods

Study population

All patients included in our study are part of the Leiden-NPSLE cohort, receiving multidisciplinary diagnostic evaluation at the Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC). The LUMC is a tertiary referral centre for SLE patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms. A detailed description of this patient cohort has been published earlier.16

After referral, patients are examined in a standardized way by a rheumatologist, neurologist, neuroradiologist, psychiatrist, vascular internist, nurse practitioner and neuropsychologist. In a multidisciplinary meeting, the final diagnosis is established based on expert opinion, after exclusion of other possible causes. All patients are classified according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1982 revised criteria for SLE.17 NPSLE syndromes are assessed according to the ACR 1999 NPSLE definitions.11 A patient with one or more neuropsychiatric symptoms directly attributed to SLE was included as an NPSLE patient in the analysis. The other patients are included as patients with non-SLE related neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Patients of 18 years and older who visited the NPSLE clinic between September 2007 and September 2015 were included in the current study. The local medical ethical committee approved and all patients signed informed consent. Data collection included sociodemographic characteristics and clinical characteristics, derived from the patient’s record. SLE disease activity was calculated with the System Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K).18

QoL assessment

QoL was assessed using the Dutch version of the SF-36. The SF-36 consists of eight subscales: Physical Functioning (PF), Role – Physical functioning (RP), Bodily Pain (BP), General Health (GH), Vitality (V), Social Functioning (SF), Role – Emotional functioning (RE), and Mental Health (MH). In addition to leading to scores on the eight subscales, the SF-36 allows scoring of two summary dimensions: physical component subscore (PCS) and mental component subscore (MCS). The component summary scores are standardized using normative data from the 1998 US general population with a mean score of 50 and a standard deviation of 10.19

The QoL of the patients in the NPSLE cohort was measured during the first visit and a comparison in QoL was made with data available from the general Dutch population20,21 and other cohorts of Dutch patients with chronic diseases: migraine,20 mood disorder,22 RA23 and lupus nephritis.24

Follow-up analysis was performed of patients that returned to the NPSLE clinic between six and 60 months after the primary visit. Follow-up analysis was performed for medical indication (e.g. evaluation of treatment effect) and patients were also approached to participate in the follow-up visit for research purposes.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 23 for Windows (IBM SPSS statistics, Chicago, IL, USA). All values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). p ≤ 0.05 is considered statistically significant. All variables had a normal distribution, therefore parametric tests were used.

SF-36 subscores and component scores were calculated at baseline. Thereafter, associations between these scores and clinical and sociodemographic variables, including age, gender, ethnicity (Caucasian, Asian, Hispanic, Black, mixed), education (low < 8 years, middle 8–16 years, high > 16 years), disease activity and disease duration were identified using linear multivariate regression analysis. Thereafter, SF-36 domains at baseline were compared with scores of patients with other chronic diseases, using the one sample T-test. In addition, a comparison in all SF-36 domains was made between patients with NPSLE or non-SLE attributed neuropsychiatric symptoms, using the unpaired T-test. Lastly, change of QoL at follow-up was calculated using the paired T-test. To detect if the amount of time between baseline and follow-up influenced the change of QoL at follow-up, a Pearson correlation coefficient analysis was performed. Comparison between QoL at follow-up between patients with NPSLE and non-SLE attributed neuropsychiatric symptoms was made using the unpaired T-test.

Results

Clinical features of study population

A total of 248 SLE patients were included in this study. Ninety-eight patients suffered from NPSLE (39.7%), the remaining patients had neuropsychiatric symptoms that could not be attributed to a specific cause. Of the 248 patients included, 104 received follow-up assessment within the duration of this study. In this follow-up sample, 64 patients had NPSLE (61.5%) at baseline.

The study population was predominantly Caucasian (67.6%) and female (89.5%), with a mean age of 42 years. Most patients were married (62.2%) and had received a medium-length education (62.3%). The mean duration of SLE until time of development of NPSLE was 8.4 ± 9.2 years. A total of 14 NPSLE syndromes were diagnosed. The mean SLEDAI score was 6.7 ± 6.5. A description of the prevalent NPSLE syndromes and medications at the time of admission are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the Leiden NPSLE clinic cohort

| Number of patients | 248 |

|---|---|

| Gender (n (%)) | |

| Female | 222 (89.5) |

| Male | 26 (10.5) |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) at enrolment | 42.23 ± 13.1 |

| Ethnicity (n (%)) | |

| Caucasian | 167 (67.6) |

| Asian | 47 (19.0) |

| Black | 20 (8.1) |

| Hispanic | 4 (1.6) |

| Mixed | 8 (3.2) |

| Single/married/other (%) | 21.1/62.2/16.7 |

| Education (n (%)) | |

| Low | 17 (6.9) |

| Medium | 154 (62.3) |

| High | 66 (26.7) |

| Unknown | 9 (3.6) |

| Disease duration, years (mean ± SD) | 8.4 ± 9.2 |

| SLEDAI score (mean ± SD) | 6.7 ± 6.5 |

| Medications (n (%)) | |

| Corticosteroids | 126 (51.0) |

| Antimalarial | 153 (61.9) |

| Immunosuppressants | 85 (34.4) |

| NSAID | 58 (23.5) |

| Aspirin | 55 (22.3) |

| Antidepressants | 37 (15.0) |

| Anticonvulsants | 31 (12.6) |

| Antipsychotics | 19 (7.7) |

| Anticoagulants | 44 (17.8) |

| Benzodiazepine | 32 (13.0) |

| NPSLE, yes (n (%)) | 98 (39.7) |

| ACR NPSLE syndrome (n (%)) | |

| Central nervous system | |

| Aseptic meningitis | 1 (0.4) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 44 (17.8) |

| Demyelinating syndrome | 1 (0.4) |

| Headache | 12 (4.9) |

| Movement disorder | 4 (1.6) |

| Myelopathy | 5 (2.0) |

| Seizure disorders | 13 (5.3) |

| Acute confusional state | 4 (1.6) |

| Anxiety disorder | 6 (2.4) |

| Cognitive dysfunction | 49 (19.8) |

| Mood disorder | 26 (10.5) |

| Psychosis | 9 (3.6) |

| Peripheral nervous system | |

| Cranial neuropathy | 2 (0.8) |

| Polyneuropathy | 5 (2.0) |

NPSLE: neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus; NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; ACR: American College of Rheumatology

Quality of life at baseline

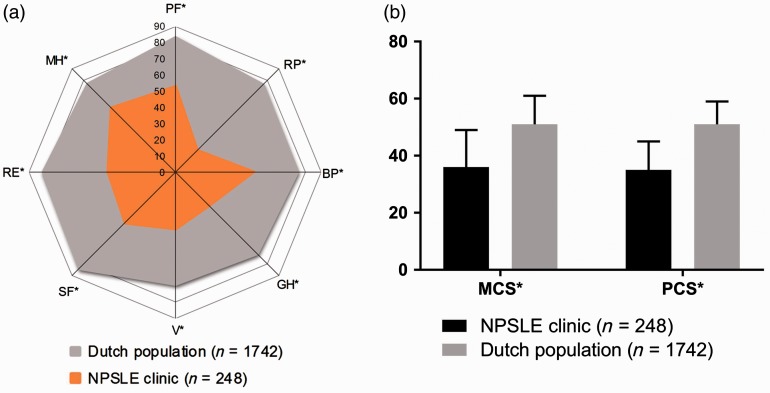

QoL at baseline is presented in Figure 1(a) and (b). The aetiology of the neuropsychiatric symptoms (SLE or non-SLE related) is not associated with the results (p > 0.05 for all subscales). Several SF-36 scores are associated with specific clinical and sociodemographic variables. Physical functioning is associated with age at baseline (estimate: −0.46, 95% confidence interval (CI) = −0.73, −0.18). In addition, general health is influenced by age at baseline (estimate 0.29, 95% CI = 0.11, 0.47), disease duration (estimate −0.02, 95% CI = −0.04, −0.00) and ethnicity (estimate −1.83, 95% CI = −3.40, −0.26). Bodily pain is influenced by ethnicity (estimate −3.68, 95% CI = −6.21, −1.14). The physical component score is influenced by the SLEDAI score (estimate −0.20, 95% CI = −0.40, −0.00).

Figure 1.

(a) Health-related quality of life using the SF-36 in patients with SLE and neuropsychiatric symptoms compared with the general Dutch population. 0 = worst quality of life, 100 = best quality of life. * = p < 0.001. (b) * = p < 0.05.

NPSLE: neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus; PF: physical functioning; RP: role functioning, physical; BP: bodily pain; GH: general health; V: vitality; SF: social functioning; RE: role functioning, emotional; MH: mental health; SF-36: Short-Form Health Survey; MCS: mental component score; PCS: physical component score

Comparison with the Dutch population and patients with other chronic diseases

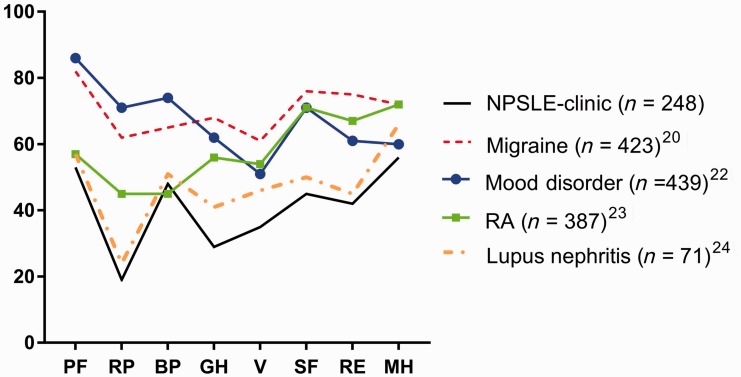

When compared with the general Dutch population, patients of the Leiden NPSLE-cohort show a significantly reduced QoL on all domains of the SF-36 at baseline. In addition, the summary scores indicate a significantly decreased QoL in both overall physical and mental aspects (p < 0.001) (Figure 1(a) and (b)). Furthermore, in comparison with patients with other chronic diseases, patients from the Leiden NPSLE clinic appear to be the most severely impaired in nearly all SF-36 dimensions of QoL (Figure 2). The physical role functioning and physical functioning are more impaired than in patients with RA. Only the subscore evaluating bodily pain is more impaired in patients with RA than in patients of the NPSLE clinic. Furthermore, patients of the NPSLE clinic also have significant lower scores in all mental and physical aspects when compared with patients with mood disorder and migraine. Lastly, when compared with patients with lupus nephritis, patients in the NPSLE clinic mainly have lower mental subscores.

Figure 2.

Health-related quality of life using the SF-36 in patients with SLE and NP symptoms, compared with patients with other (chronic) diseases in the Dutch population.20–24

PF: physical functioning; RP: role functioning, physical; BP: bodily pain; GH: general health; V: vitality; SF: social functioning; RE: role functioning, emotional; MH: mental health; NPSLE: neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; SF-36: Short-Form Health Survey

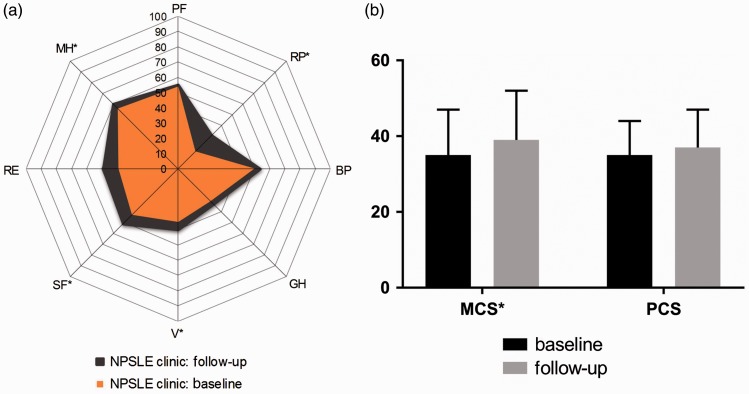

Quality of life at follow-up

For 104 patients information about QoL at follow-up was available. Time between visits ranged from 5.5 to 59.1 months, with a median of 15.4 months. Figure 3(a) shows the scores on the eight SF-36 subscales at baseline and at follow-up. All subscale scores show some improvement; of which the physical role functioning (p = 0.001), social role functioning (p = 0.005), vitality (p = 0.007) and mental health (p = 0.042) show a significant increase between baseline and follow-up. The MCS showed a significant increase at follow-up as well (p = 0.012), whereas the PCS showed no difference between baseline and follow-up (p = 0.239) (Figure 3(b)). Differences in scores at follow-up were affected by aetiology of the neuropsychiatric symptoms. In patients with non-SLE related neuropsychiatric symptoms (n = 40), a significant change was identified in physical role functioning (p = 0.001), social role functioning (p = 0.007), vitality (p = 0.023) and mental health (p = 0.019) and mental component score (p = 0.038). However, in patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms related to SLE (n = 64), no significant change in any subscale was detected. Pearson correlation coefficient did not show an association between time between baseline and follow-up visit and any of the subscores or component scores.

Figure 3.

Health-related quality of life at baseline and follow-up of 104 patients that visited the NPSLE clinic.

* = p < 0.05.

NPSLE: neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus; PF: physical functioning; RP: role functioning, physical; BP: bodily pain; GH: general health; V: vitality; SF: social functioning; RE: role functioning, emotional; MH: mental health; MCS: mental component score; PCS: physical component score

Discussion

Our data show that the health-related QoL in patients with SLE presenting neuropsychiatric symptoms is extremely reduced in both physical and mental domains, regardless of aetiology. In particular, we found that the subscales general health and role limitations due to physical health and emotional problems were the most impaired. Our results also show that the QoL of patients with SLE and neuropsychiatric symptoms is severely impaired when compared with the general Dutch population and patients with other chronic diseases. All aspects of the mental and physical scores are extremely low in our patient sample, illustrating the severe impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms in SLE.

Furthermore, the follow-up analysis only showed a significant change in QoL in patients with non-SLE related neuropsychiatric symptoms. A possible explanation for improvement of QoL is intervention (i.e. psychological care, medical treatment with drugs) between the first visit and follow-up. However, treatment is prescribed for both NPSLE patients and patients with non-SLE related neuropsychiatric symptoms, and only the latter showed significant improvement at follow-up. Another possible explanation is that the diagnostic work-up and multidisciplinary approach reassured patients with non-SLE related neuropsychiatric symptoms, thereby increasing the QoL.

Our data are rather similar to those reported previously by Hanly et al., although we analysed QoL per patient instead of per neuropsychiatric event. Their research also demonstrated that the QoL in patients with neuropsychiatric events is reduced regardless of the neuropsychiatric aetiology.6 However, we found different results regarding QoL at follow-up. Our results show that improvement in QoL over time is only present in patients with non-SLE related neuropsychiatric symptoms, whereas previous studies showed better disease outcome for SLE-related neuropsychiatric symptoms.6,10 Lastly, in our study, we did not find more improvement in early disease than in longstanding disease, which other studies have suggested.4,6

This study has several limitations. First of all, the time between baseline and follow-up ranged between six and 60 months, which could mask a difference between short-term and long-term outcome of QoL. However, no difference in change between early and late follow-up was detected in the correlation coefficient analysis. Secondly, because NPSLE syndromes are very diverse, analysing the group as a whole might conceal differences in QoL in different syndromes. Lastly, as the LUMC is a tertiary referral centre for SLE patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms, generalization of our outcomes to all SLE patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms should be done with this consideration in mind.

Regarding future research, the SF-36 is only one of the many possible ways to examine QoL: it is a generic QoL-scale, applicable to any person, with or without medical conditions. Disease specific questionnaires such as the LupusQoL and SLE Symptom Checklist can be used in addition to the generic SF-36.25 Furthermore, novel methods such as drawings may have added value in the assessment of QoL in persons with SLE and other chronic diseases.26 In addition, to improve our understanding of QoL over time, QoL has to be assessed more frequently in a longitudinal study. Previous research of QoL in patients with SLE has evaluated specific aspects contributing to QoL, such as self-efficacy, using this approach.27 Lastly, a recent article bij Magro-Checa et al. demonstrated that inflammatory NPSLE has a better outcome in terms of QoL than non-NPSLE and ischemic NPSLE events, whereas we found improvement in the non-NPSLE group and not in the NPSLE group as a whole.28 It would be interesting to look further into the differences between these specific subgroups in order to find possible ways to improve the QoL.

Our research also has several clinical implications, most importantly that the current medical policy deserves critical analysis and needs to focus more on neuropsychiatric symptoms in order to improve QoL. There are many factors that could contribute to the QoL and thereby be a valuable addition in the treatment of SLE patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms. First of all, patient education that combines elements of efficacy enhancement, social support and problem solving has been shown to contribute to optimal care.29 With adequate support patients can be more actively involved and perceive an increased sense of control, which reduces the chance of anxiety and depression.30 Secondly, health professionals could consider the close social network of the patient as well, as the recognition and understanding of the emotional needs by the partner, friends and relatives are extremely important.27–31 Nurses can fulfil a key role in the above mentioned supportive care and their contribution, together with the medical care of doctors, has been proven to be invaluable.31 Lastly, patients with different chronic diseases, including SLE, have benefited from cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), which focuses on coping strategies.32 CBT in patients with SLE addressing cognitive restructuring, relaxation techniques and training in social skills has shown to improve the QoL in subscales such as physical role functioning and general health perceptions, which were particularly reduced in our study.29 A meta-analysis by Van Beugen et al. showed that internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for patients with chronic somatic conditions improved, amongst others, disease-specific QoL.33 The SLE Needs Questionnaire (SLENQ) is a reliable assessment tool to evaluate psychosocial needs, and is not yet used routinely. Structural use of the SLENQ will help identify patients that require extra attention.34 These SLE patients might benefit from therapies focusing on coping strategies and cognitive rehabilitation, in addition to medical treatment for neuropsychiatric symptoms.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that QoL is severely reduced in SLE patients with neuropsychiatric symptoms and that more attention should be given to this important aspect of patient care. Implementing biopsychosocial care, including self-management approaches, could improve QoL in these patients.

Acknowledgement

RCM and LJJBV contributed equally.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Schipper H, Clinch J, Powell V. Definitions and conceptual issues. In: Spilker B. (eds). Quality of life assessments in clinical trials, New York: Raven Press, 1990, pp. 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McElhone K, Abbott J, Teh LS. A review of health related quality of life in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2006; 15: 633–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jolly M. How does quality of life of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus compare with that of other common chronic diseases? J Rheumatol 2005; 32: 1706–1708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urowitz M, Gladman DD, Ibanez D, et al. Changes in quality of life in the first 5 years of disease in a multicenter cohort of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res 2014; 66: 1374–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuriya B, Gladman DD, Ibanez D, Urowitz MB. Quality of life over time in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 59: 181–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanly JG, Urowitz MB, Su L, et al. Prospective analysis of neuropsychiatric events in an international disease inception cohort of SLE Patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2010; 69: 529–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanly JG, McCurdy G, Fougere L, Douglas JA, Thompson K. Neuropsychiatric events in systemic lupus erythematosus: Attribution and clinical significance. J Rheumatol 2004; 31: 2156–2162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanly JG, Urowitz MB, Sanchez-Guerrero J, et al. Neuropsychiatric events at the time of diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus: An international inception cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2007; 56: 265–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanly JG. The neuropsychiatric SLE SLICC inception cohort study. Lupus 2008; 17: 1059–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanly JG, Su L, Farewell V, McCurdy G, Fougere L, Thompson K. Prospective study of neuropsychiatric events in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2009; 36: 1449–1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ACR Ad Hoc Committee of Neuropsychiatric Lupus Nomenclature. The American College of Rheumatology nomenclature and case definitions for neuropsychiatric lupus syndromes. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42: 599–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magro-Checa C, Zirkzee EJ, Huizinga TW, Steup-Beekman GM. Management of neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus: Current approaches and future perspectives. Drugs 2016; 76: 459–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bachen EA, Chesney MA, Criswell LA. Prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61: 822–829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Touma Z, Gladmann DD, Ibanez D, Urowitz MB. Is there an advantage over SF-36 with a quality of life measure that is specific to systemic lupus erythematosus? J Rheumatol 2011; 38: 1898–1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanly JG, Urowitz MB, Jackson D, et al. SF-36 summary and subscale scores are reliable outcomes of neuropsychiatric events in systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70: 961–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zirkzee EJM, Steup-Beekman GM, van der Mast RC, et al. Prospective study of clinical phenotypes in neuropsychiatric systemic lupus erythematosus; multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and therapy. J Rheumatol 2012; 39: 2118–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American College of Rheumatology. 1997 Update of the 1982 American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1997; 40: 1725–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gladman DD, Ibañez D, Urowitz MB. Systemic lupus erythematosus disease activity index 2000. J Rheumatol 2002; 29: 288–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JE, Gandek B, Kosinski M, et al. The equivalence of SF-36 summary health scores estimated using standard and country specific algorithms in 10 countries: Results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51: 1167–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PDA, et al. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 health survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51: 1055–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zee van der KI, Sanderman R. Het meten van de algemene gezondheidstoestand met de RAND-36 [Assessing health status with the RAND-36, manual], Groningen: Research Institute Share, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kruijshaar ME, Hoeymans N, Bijl RV, Spijker J, Essink-Bot ML. Levels of disability in major depression: Findings from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). J Affect Disord 2003; 77: 53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ten Klooster P, Vonkeman H, Taal E, et al. Performance of the Dutch SF-36 version 2 as a measure of health-related quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013; 11: 77–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arends S, Berden JH, Grootscholten C, et al. Induction therapy with short-term high-dose intravenous cyclophosphamide followed by mycophenolate mofetil in proliferative lupus nephritis. Neth J Med 2014; 72: 481–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grootscholten C, Ligtenberg G, Derksen RHWM, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: Development and validation of a lupus specific symptom checklist. Qual Life Res 2003; 12: 635–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daleboudt GM, Broadbent E, Berger SP, Kaptein AA. Illness perceptions in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and proliferative lupus nephritis. Lupus 2011; 20: 290–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazzoni D, Cicognani E, Prati G. Health-related quality of life in systemic lupus erythematosus: A longitudinal study on the impact of problematic support of self-efficacy. Lupus 2017; 26: 125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magro-Checa C, LJJ Beaart-van de Voorde, HAM Middlelkoop et al. Outcomes of neuropsychiatric events in systemic lupus erythematosus based on clinical phenotypes; prospective data from the Leiden NP-SLE Cohort. Lupus 2017; doi: 10.1177/0961203316689145. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Karlson EW, Liang MH, Eaton H, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a psychoeducational intervention to improve outcomes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50: 1832–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beckerman NL, Auerbach C, Blanco I. Psychosocial dimensions of SLE: Implications for the health care team. J Multidisc Healthcare 2011; 4: 63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferenkeh-Koroma A. Systemic lupus erythematosus: Nurse and patient education. Nurs Stand 2012; 26: 49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Navarrete-Navarrete N, Peralta-Ramírez MI, Sabio JM, Martínez-Egea I, Santos-Ruiz A, Jiménez-Alonso J. Quality-of-life predictor factors in patients with SLE and their modification after cognitive behavioural therapy. Lupus 2010; 19: 1632–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Beugen S, Ferwerda M, Hoeve D, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with chronic somatic conditions: A meta-analytic review. J Med Internet Res 2014; 16: e88–e88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moses N, Wiggers J, Nicholas C, Cockburn J. Development and psychometric analysis of the systemic lupus erythematosus needs questionnaire (SLENQ). Qual Life Res 2007; 16: 461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]