INTRODUCTION

Stakeholder engagement in research has received increasing attention in recent years.1, 2 The term “stakeholder engagement” refers to the process of meaningful involvement of those who are engaged in making decisions about programs.3 Engaging members of the target population is often key to improving the relevance of the issues studied, the procedures used for study, and the interpretation of outcomes of research studies, health promotion activities, and disease prevention initiatives.4, 5, 6 The utility of stakeholder engagement has been well established in the literature,7, 8, 9 but there are few examples of measurement and evaluation of the degree to which stakeholders are engaged in these activities and the impact of engagement on positive outcomes. These types of evaluations have been limited in scope, and largely focused on qualitative approaches.10, 11, 12, 13, 14 Qualitative methods cannot be easily compared across programs or institutions.15 Necessary reliability and validity information describing self‐reported levels of stakeholder engagement are also lacking, and is essential to identifying the impact of engagement on the scientific process and scientific discovery.

METHODS

We present the results of a systematic review of the existing quantitative measures of stakeholder engagement in published research and programs. We used the methods of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA16) to review the literature on measures of stakeholder engagement.

Definition of sytakeholder engagement

We defined stakeholder engagement as the involvement of people who may be affected by a research finding or program. We included any type of stakeholder that was available in the literature, and included all settings and situations. We did not limit the search to research or intervention projects, because we reasoned that the field was relatively new, and therefore we might find good measures in multiple areas from which to draw our search. All authors contributed substantially to multiple aspects of the article: (1) the concept and design or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) the drafting or revision of the article, and (3) approval of the final version.

Search methods

We searched the peer‐reviewed literature using two electronic bibliographic databases: PubMed (web‐based) and the Web of Science (web‐based). These database searches for all years until 2013 were conducted between July and September 2014. The 2014 search was conducted in January 2016.

Phase I: Searching the literature

With assistance from a reference librarian, we generated a master list of search terms to use with both databases. The following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms were selected: stakeholder engagement, community engagement, community engaged research. These terms were then entered into the two chosen databases using quotations to ensure that search terms were verbatim and separated by “OR” to ensure inclusion if any of the search terms were present. A master list of articles was created using Endnote X8 citation management software from these search results. All published reports from 1973 to 2014 were identified and retrieved.

Phase II: Abstract review

Two authors independently reviewed each title and abstract using predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria and resolved disagreement through rereview and discussion until they reached consensus. Included articles appear in English, in a peer‐reviewed journal, report original research, and appear to use a quantitative measure for at least one construct reported to measure stakeholder engagement. The full texts of articles whose abstracts met our inclusion criteria were retrieved and then examined for further inclusion/exclusion criteria. Our primary exclusion criterion was an article that does not contain stakeholder engagement, then subsequently, lack of quantitative measures.

Phase III: Data Abstraction

To ensure consistency in data abstraction, we created a standardized codebook for use by all authors, based on a prior measurement review. All authors reviewed the same five studies using the codebook and identified and resolved disagreements in coding. The codebook was thereafter revised. Included studies were distributed among seven coders for data abstraction. For all studies included in the review, two authors independently coded and compared their results. Coding discrepancies within pairs were resolved through discussion among authors. We opted for this group consensus method because of the enormous variability in terminology used to describe engagement characteristics and constructs across studies.

The variables extracted included constructs measured, names of measures, stakeholder group engaged, type of engagement project, whether or not the measurement was part of a training exercise, and relationship of construct to study outcome (if engagement was assessed to be related to the dependent variable in the study). Data were entered into Excel files and evidence tables were constructed, organized by article first author, and stratified by type of construct. We divided the abstracted measures into (1) measures that were collected using participant‐reported methods, no matter how the self‐report was collected, such as online, paper and pencil methods (n = 53), and (2) observational methods, defined as a variable that asked researchers to observe and quantify behaviors relevant to engagement, such as attendance at a public event (n = 51).

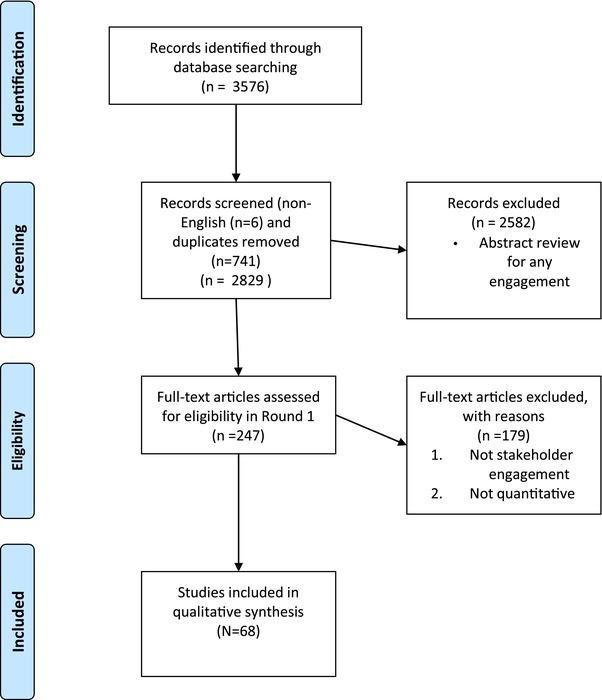

FLOW OF ARTICLE REVIEW

Figure 1 contains the data on article eligibility and coding patterns. The search identified 3,576 (PubMed n = 1,112, Web of Science n = 2,464) articles using our key words. Six articles were excluded for being non‐English language (one Chinese, two German, two French, and two Spanish language articles). The abstracts of these articles were translated and determined to not impact the outcome of this review. From the remaining articles, 741 were excluded for being duplicate articles found because the databases used had some degree of overlap. After initial screening, we identified 2,829 non‐duplicate English language titles (see Figure 1). Of these, 2,582 were excluded during the abstract and title screening phase of the review, leaving a total of 247 articles. We excluded 179 articles at the final coding stage because they ultimately did not meet our eligibility criteria when the full‐length article was coded and discussed. A total of 68 articles contained quantified measures of stakeholder engagement and met our final criteria.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram.

COMPILATION OF REVIEWED MEASURES

Table 1 contains the 53 participant‐reported measurements of stakeholder engagement found in 38 studies identified in our search. In each of these studies, participants indicated the extent of their engagement in the project using responses to one or more scales. The types of projects included here were broad: research projects, community input projects, and interventions. As seen from this table, none of the articles use the same stakeholder measure. Only a small number of reviewed articles (5 out of 53; 13%) reported psychometric data about the measure. Some of the measures (5 out of 53; 13%) had reliability calculated in the form of alpha coefficients, yet none of the scales presented any information on content validity or on other types of validity (i.e., criterion, construct). The stakeholder populations targeted in these studies widely varied, from members of a defined general public to participants in community groups and members of advisory boards. Only 25 of 53 (47%) measures reported assessment and testing of the significance of the relationship of participant‐reported engagement measure to outcome. Of those that assessed the relationship of measure to outcome, 100% of the studies indicated a significant relationship between engagement measure and at least one of the outcomes.

Table 1.

Observational measures of engagement 1973–2014

| Citation | Type of project | Measure of Engagement | Description of measures | # items used for measurement | Stakeholder studied | Statistics on measure? | Relate measure to outcome? | If yes, what is the result? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17. An, 2008 | Intervention | Utilization | Utilization measures capturing use of quitplan.com's informational resources | 4 | Tobacco users who are new registrants to quitplan.com | None | Yes | Use of interactive quitting tools were associated with increased abstinence rates |

| 17. An, 2008 | Intervention | Utilization | Utilization measures capturing use of quitplan.com's interaction with the online community | 3 | Tobacco users who are new registrants to quitplan.com | None | Yes | One‐to‐one messaging with other members of the online community, was associated with increased abstinence rates |

| 18. Andreae, 2012 | Cross‐sectional Survey | Referrals | Referrals from community members | 1 | Members of the community in a network around primary care offices | None | No | |

| 18. Andreae, 2012 | Cross‐sectional survey | Involvement | Referrals from primary care office staff | 1 | Staff of primary care offices who were engaged to participate in recruitment process | None | No | |

| 18. Andreae, 2012 | Cross‐sectional Survey | Recruitment | Referrals from community members | 1 | Community members hired to facilitate recruitment | None | No | |

| 19. Andrews, 2008 | Survey | Citizenship‐related activities | A list of opportunities for public participation in local government; respondents select the most important activities undertaken. | 1 | English local government officers | None | No | |

| 19. Andrews, 2008 | Survey | Citizen empowerment | Various indicators including voter turnout, website hits, attendance at events; some used Best Value Performance Indicators or community safety indicators | Many; varied across authorities | English local government officers | None | No | |

| 20. Ayuso, 2011 | Cross‐sectional survey | Internal Stakeholder Engagement | Percentage of skilled employees and executives receiving a regular (e.g., at least once per year) formal evaluation of their performance, percentage of employees to follow a company training program specific to their job category, percentage of employees hired based on a validated recruitment process/selection test. | 3 | Employees | Alpha > .60 | Yes | Knowledge sourced from engagement with internal stakeholders, and engagement with external stakeholders contributed to a firm's sustainable innovation orientation. |

| 20. Ayuso, 2011 | Cross‐sectional survey | External Stakeholder Engagement | 1) How the external company engages with external stakeholders and 2) does the company regularly conduct satisfaction surveys or perception studies of the following stakeholders? | 2 | Outside companies | Alpha close to .7 | Yes | The engagement was correlated with company's sustainable innovation orientation. |

| 21. Clark, 2010 | Intervention | Coalition Self‐Assessment Survey | Assesses level of involvement of individual coalition members suing Likert‐type scale (four categories = peripheral, intermittent, ongoing, core) | Not Reported | Coalitions of community residents and community‐based organizations | No | Yes | Coalitions with more engaged (core or ongoing) partners had greater asthma policy and systems changes |

| 21. Clark, 2010 | Intervention | Coalition tracking | Assesses level of involvement of individual coalition members suing Likert‐type scale (four categories = peripheral, intermittent, ongoing, core) | Multiple | Coalitions of community residents and community‐based organizations | No | Yes | Coalitions with more engaged (core or ongoing) partners had greater asthma policy and systems changes |

| 22. Fahrenwald, 2013 | Longitudinal study preparation | Participation | Number of each type of outreach/engagement activity | Multiple | Government, healthcare systems, social services, child care, churches and non‐profits, media, major employers, other grassroots partners | No | Yes | Recruitment outcomes |

| 23. Fothergill, 2011 | Community placed research | Community engagement | Reports of regular church attendance (once per week or more) and participation in any secular organizations | unclear | Mothers of a cohort of first graders from Woodlawn, a largely Afr. Am. Community on the south side of Chicago | No | Yes | Association between social integration and health significant health |

| 23. Fothergill, 2011 | Community placed research | Community engagement | Reports of regular church attendance (once per week or more) and participation in any secular organizations | 30 | Mothers of a cohort of first graders from an African American community in Chicago | No | Yes | Persistently engaged women less likely to report anxious or depressed mood than those with early CE only. Persistent and diverse CE was more highly associated with better physical functioning than was persistent CE. |

| 24. Frew, 2008 | Cross‐sectional | Community Involvement | Survey of evaluative measures, demographics, social interaction, and health information‐seeking behaviors. | 32 | Attendees of public LGBT and AIDS awareness events in Atlanta | No | Yes | Community involvement associated with likelihood to return to another HIV vaccination research event in the future. |

| 25. Frew, 2011 | Cross‐sectional | Community Engagement in HIV Vaccine Research | Cross‐sectional survey consisting of evaluative measures, demographics, social interaction, and health information‐seeking behaviors was conducted. Multivariate analysis. | 3 | Prospective study participants at public events | No | No | |

| 26. Galichet, 2010 | Application analysis | Level of stakeholder inclusiveness in the application process | Assessment of inclusiveness based on 4 criteria: 1) evidence of Health Systems Coordination Committee meeting 2x/year, 2) at least 4 int'l stakeholders participate in application process, 3) presence of 1 or more‐ private sector, civil society, independent health professionals, academics, 4) evidence of stakeholder attendance at prep meetings. Each criteria = 1 point. Applications rated 1–4 (highly inclusive to non‐inclusive). | 4 | Gov't stakeholders, external stakeholders in‐country, int'l (i.e., Ministry of Finance, NGOs, health professionals) | No | Yes | Higher levels of inclusiveness correlated positively with application approval Strong correlation between the evaluation of inclusiveness and the assessment of the proposals by the Independent Review Committee. |

| 27. Gregson, 2013 | Cross‐sectional survey (at two time points) | Participation | Self‐reported participation in activities of local community organizations to which participants reported membership. | Unclear | 5260 adults interviewed in two consecutive rounds Between 2003–2008 | No | Yes | No relationship between participation and outcomes |

| 28. Hess, 2001 | Cross‐sectional surveys | Citizen input index | Index combining data from seven situations where engagement in district is possible | 7 | District is focus | No | No | |

| 29. Hood, 2010 | Online questionnaire | Level of community engagement | Studies categorized in either Level 1 or Level 2 of community engagement. Level One included activities that had CBPR principles such as a community advisory Group or other meaningful involvement. | 2 | NIH‐funded Investigators at a large Midwestern University that has an NIH CTSA | No | No | |

| 29. Hood, 2010 | Community connected research | Level of community engagement | Focus groups for community input; MOA/MOU with non‐univ group; data collection not at univ site; special events or recognition for participants; share study findings with community reps. | 5 | NIH‐funded Investigators at a large Midwestern University that has an NIH CTSA | No | No | |

| 29. Hood, 2010 | Community connected research | Community involvement in individual steps of research process | Online survey e‐mailed to principal investigators of recent NIH‐funded studies | 11 | NIH‐funded Investigators at a large Midwestern University that has an NIH CTSA | No | No | |

| 30. Hughes, 2006 | National random telephone survey | Community Life | Community Connections (number of group memberships), Community Norms (feelings of trust and reciprocity in community) | 2 | Australian adults who responded to 'Families, Social Capital, and Citizenship' Project.' National random sample | No | Yes | Family life measures predicted both measures of community life |

| 31. Jolibert, 2012 | Cross‐sectional survey | Participation | Counts of stakeholders involved in the biodiversity research project | 1 | Selected project coordinators and partners in 38 biodiversity research projects | No | No | |

| 31. Jolibert, 2012 | Cross‐sectional survey | Communication | Types of communication between research projects and stakeholders | 1 | Selected project coordinators and partners in 38 biodiversity research projects | No | No | |

| 32. Kagan, 2012 | Survey | Community involvement | How people viewed (a) the frequency of activities indicative of community involvement, (b) the means for identifying, prioritizing, and supporting CAB needs, and (c) mission and operational challenges. | 25 | Community advisory boards | No | No | |

| 32. Kagan, 2012 | Survey | Frequency of activities reflective of community involvement | Rated (on a 7‐point Likert‐type scale of 1 [never] to 7 [always]), the perceived frequency of occurrence of 25 best practice activities, 11 of which were CAB‐based and 14 describing RS functions. | 11 | Community advisory boards | No | No | |

| 32. Kagan, 2012 | Survey | Relevance of research activities | Rated (on a 7‐point Likert‐type scale of 1 [never] to 7 [always]), the perceived frequency of occurrence of 25 best practice activities, 11 of which were CAB‐based and 14 describing RS functions. | 6 | Community advisory boards | No | No | |

| 32. Kagan, 2012 | Survey | Communication and collaboration activities | Rated (on a 7‐point Likert‐type scale of 1 [never] to 7 [always]), the perceived frequency of occurrence of 25 best practice activities, 11 of which were CAB‐based and 14 describing RS functions. | 8 | Community advisory boards | No | No | |

| 33. Kamuya, 2013 | Cross‐sectional survey | Participation | Number of meetings attended number of members | 2 | Community representatives | No | No | |

| 34. Kyle, 2010 | Cross‐sectional Survey | Ratings of home and community protection activities | Respondents first indicated Y/N to whether they did specific activity. Then rated likelihood of doing activity in the future along 5‐point scale Items grouped into 4 conceptual domains. | 13 | Residents in Southern CA; primarily white, educated men | No | Yes | Community attachment was strongly predictive of community‐based activities. |

| 35. Litt, 2013 | Cross‐sectional Survey | Stakeholder engagement. | Questions on 10 community activities on a 5‐point Likert scale (1 = never, 2 = rarely [<2 times], 3 = sometimes [2–5 times], 4 = often [most of the time], 5 = very frequently or ongoing) (19). | 15 | Active living collaborations | No | No | |

| 36. McNaughton, 2012 | Community engagement case study | engagement activities | number of each type of outreach/engagement activity | 3 | Community members and community leaders (Australian) | No | Yes | |

| 37. Nahar, 2012 | Intervention | Attendance | Number of and attendance at women' s groups | 2 | women of childbearing age and new married in rural Bangladesh | No | Yes | Approximately 29% of women who gave birth and were interviewed as part of the community‐surveillance system during the period January 2009 to June 2010 reported attending women's groups, compared to 3% prior to scale‐up. |

| 38. O'Brien, 2009 | Intervention | Change in the use of community services | The number of services used by each patient one year before the CTO was issued (range 1–3). Measures the number of services used one year after the CTO is issued (range 1–4). | 1 | Psychiatric patients in Ontario, Canada | No | Yes | A significant increase in the number of community services was found for patients following the issuance of a CTO. |

| 39. Overstreet, 2005 | Cross‐sectional survey | Community engagement behaviors (predictor variable) | Parent reporting of voting, church attendance, and activity at their local community center. | 3 | 159 economically disadvantaged African American parents living in an urban setting | No | Yes | Parent engagement and contextual variables predicted school involvement outcomes, but specific predictors varied by child's grade level. |

| 39. Overstreet, 2005 | Cross‐sectional survey | Parental involvement in schooling (outcome variable) | Parent reporting of visiting their child's classroom, attending events at school, and membership of the parent–teacher organization. Summed to composite measure. | 4 | 159 economically disadvantaged African American parents living in an urban setting | alpha = .62 | Yes | Parent engagement and contextual variables predicted school involvement outcomes |

| 40. Phillips, 2014 | Cluster randomized trial | Competency in partnership, collaboration, and community engagement | Self‐assessment of competency in partnership collaboration and community engagement | 1 | Mentees in the research to reality pilot mentorship program of NCI | No | No | |

| 41. Pitama, 2011 | Description of CBPR epidemiological study | Study response rates in three groups of study samples | The final disposition for each person selected was coded according to the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) guidelines for in‐person household surveys and response rates were calculated conservatively using Response Rate 1 which includes all persons of unknown eligibility in the denominator. | 1 | Wairoa Maori, Christchurch Maori, Christchurch non‐Maori | No | Yes | Maori research approach successfully recruited participants |

| 42. Polson, 2013 | Cross‐sectional survey | How many formal or informal groups or clubs do you belong to, in your area, that meet at least monthly? | Count of formal or informal groups or clubs | 1 | general male public | Factor loading from principal component analyses presented | No | |

| 43. Rinner, 2009 | GIS case study | Participation (type and amount) | Measure of participation in the ArguMap application. Factors: registrations, active participants, starter threads, contributions, new threads, replies (first‐order, second‐order, third‐order, and fourth‐order). | 10 | Residents within or near the 'Queen West Triangle' in Toronto | No | No | |

| 44. Rose, 2008 | Cross‐sectional survey | Active engagement with thecommunity | Measured frequency of active and passive types of community involvement. | 5 | Older adults in 7 Latin American and Caribbean cities | No | Yes | No significance in the association active community engagement and active living. |

| 45. Saewyc, 2008 | Cross‐sectional survey | Community engagement | Level of involvement in extracurricular activities and volunteering. | Unclear | Adolescents in British Columbia | No | Yes | High levels of protective factors were strongly linked to lower rates of self‐reported risk behaviors and greater health. |

| 46. Shah, 2002 | Cross‐sectional Survey | Civic engagement | An additive index from three items. | 3 | Residents of defined community | alpha = .3 | Yes | Internet use related to civic participation |

| 47. Sirin, 2011 | Cross‐sectional survey | Developmental Assets Profile (Search Institute, 2004). | Single item measure of community engagement (In the past year, have you worked with others in your neighborhood to address a problem or improve something?) | 1 | general male public | No | No | |

| 48. Tiffany, 2012 | Intervention | Intensity | Analysis of how long involved in program | 1 | Adolescents engaged in after school activities in NYC | Extensive factor analyses reported; alphas = .66‐. | No | |

| 48. Tiffany, 2012 | Intervention | Duration | Analysis of how long involved in program | 1 | Adolescents engaged in after school activities in NYC | Extensive factor analyses reported; alphas = .66‐. | No | |

| 49. Van Voorhees, 2008 | Survey | Community environment and engagement | Neighborhood relations, community involvement, religious activities, delinquency, and adverse events. | 15 | Representative sample of U.S. adolescents in grades 7–12 with oversampling of African American youth from high educational backgrounds | No | Yes | A supportive community and constructive involvement were related to new‐onset depressive episodes. |

| 50. Westfall, 2012 | Survey | community engagement | Participation with new colleagues | 2 | Conference attendees | No | No | |

| 51. Wilkins, 2013 | Intervention | Inventory of community involvement | Inventory made up of (1) Number and type of community representatives (CRs) with formal roles in each CTSA. (2) Roles of CRs in the CTSAs. (3) Inclusion of CRs in committee and overall leadership. (4) Policies that govern CRs involvement. (5) Time commitments expected of CRs. (6) Types and amount of compensation to CRs. (7) Best practices in engaging CRs. (8) Barriers to engaging CRs. | 8 | CTSAs | No | No |

A total of 50 separate observational measures were used to assess stakeholder engagement by counting or recording behaviors, from a total of 34 articles identified in the search (Table 2). The observational measures of engagement included “counts of referrals” and “attendance at events.” No reliability data were presented along with the identification of each measure in this table. No attempts were made in any of the studies to support the validity of the observational measures of engagement through measuring a hypothetically related construct alongside the observational measures. Many of the measures were related to outcomes as part of the study but the outcome testing used a variety of measures.

Table 2.

Participant‐reported measures of engagement, 1973–2014

| Citation | Type of project | Measure of engagement | Description of measures | # items used for measurement | Stakeholder studied | Statistics on measure? | Relate measure to outcome? | If yes, what is the result? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 52. Algesheimer, 2005 | Survey | Community identification | Strength of the consumer's relationship with the brand community. | 5 | Car club members | alpha = .92 | Yes | Community engagement related to normative community pressure |

| 52. Algesheimer, 2005 | Survey | Community engagement | Consumer's intrinsic motivations to interact and cooperate with community members. | 4 | Car club members | alpha = .88 | Yes | Community engagement related to normative pressure positively; community participation intentions, community recommendation intentions, membership continuance intentions |

| 19. Andrews, 2008 | Survey | Effective citizenship | Importance of supporting citizenship through engagement, and delivery structures (government departments) utilized to do so | 2 | English local government officers | No | No | |

| 19. Andrews, 2008 | Survey | Engaging local citizens | Successful citizenship‐related activities to build culture of engagement in local government, and changes in internal working practices to enhance this. | 2 | English local government officers | No | No | |

| 20. Ayuso, 2011 | Cross‐sectional survey | Customer and employee engagement | Single item on how the company incorporates customer feedback. For employees: lay‐offs and worker displacement policies, company systems for collecting and handling employee grievances and complaints, company‐specific job training, and selection rigor in company recruiting systems. | 1 and 4 | Employees and customers | No | Yes | engagement related to corporate social responsibility measured in terms of fiscal investment in socially responsible areas |

| 53. Brown, 2003 | Cross‐sectional survey | Future service | Likelihood of practicing in underserved areas | 1 | Practitioners of community and public health | No | No | |

| 54. Bruning, 2006 | Cross‐sectional survey | Resident engagement with the local university | Attendance a public event at the university in the past 6 months. | 1 | Local residents | No | Yes | Attendance a university event is positively associated with respondent's positive perception of the university, and consideration of the university as an asset to the community. |

| 55. Chiu, 2005 | Cross‐sectional Survey | Cynicism about community engagement | "I don't see the point in participating in social services or community affairs, there is not much you can change." | 1 | Employed Hong Kong residents | No | Yes | Cynicism about community engagement is the outcome variable; 5 categories of predictor variables were tested. |

| 55. Chiu, 2005 | Cross‐sectional Survey | Judgment of a good society | Importance of having more people who are willing to serve that society in a good society | 1 | Employed Hong Kong residents | No | Yes | Increased importance placed on having more people willing to serve in a good society was found to predict less cynicism about community engagement. |

| 55. Chiu, 2005 | Survey | Perception of deprivation | Other people having more opportunities | 1 | Employed Hong Kong residents | No | Yes | Increased perception of one's own social deprivation was found to predict increased cynicism about community engagement. |

| 55. Chiu, 2005 | Survey | Perception ofbrk one's value to society | "I feel valued by society" | 1 | Employed Hong Kong residents | No | Yes | Decreased perception of value to society was found to predict increased cynicism about community engagement. |

| 55. Chiu, 2005 | Survey | Social Trust | General view of trusting others; Levels of trust in five groups of people. Mean of these values taken as composite variable. | 2 | Employed Hong Kong residents | No | Yes | Increased social trust found to predict less cynicism about community engagement. |

| 56. Chung, 2009 | Survey | Community engagement | The perception that individual problems (in the study, depression and mental wellness) are problems of the community as a whole, on a 5 point scale (ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree) | 4 | Eligible attendees at the Talking Wellness events | No | Yes | Collective efficacy to improve depression care related to community engagement |

| 56. Chung, 2009 | Survey | Collective efficacy | Ability of group to improve depression care | 1 | Eligible attendees at the Talking Wellness events | Factor analysis mentioned but no data reported | Yes | Collective efficacy related to community engagement in terms of addressing depression. In confirmatory analyses, exposure to spoken word presentations and previous exposure to CPPR initiatives increased perceived collective efficacy |

| 57. Beringer, 2012 | Cross‐sectional Survey | Stakeholder engagement' | Two‐dimensional, 6 × 9 question matrix: Stakeholders marked a cross next to the position in the organization responsible for each of the nine specified activities. | 9 | Internal stakeholders of 223 portfolios, managers who were supposed to be operatively involved in project portfolio management processes. | No | No | |

| 58. Cuillier, 2008 | Cross‐sectional Survey | Attitudes toward community engagement | Importance of six activities in the respondent's life. | 6 | Public via random‐digit dial national phone surveys | alpha at least .70 | Yes | Community engagement is positively related to support for press access. |

| 59. Davis, 2012 | Cross‐sectional survey | Questions on engagement with ARS | Survey of participants on their views of using the ARS agreed or strongly agreed that they felt comfortable sharing their thoughts and opinions | 3 | Town hall meeting participants | No | No | |

| 60. De Freitas, 2013 | Cross‐sectional survey | Stakeholders' views and understanding of the public participation process | Survey: choose among a set of five definitions for an effective communication and engagement process. | 1 | Participants were representative of diverse and key stakeholder groups and sectors in the region | No | No | |

| 60. De Freitas, 2013 | Cross‐sectional survey | Perceptions of public participation processes | Ratings of the level of importance (with categories 1 = not at all important to 5 = extremely important) for 17 statements about possible outcomes and attributes of an effective engagement program in natural resource management. | 1 | Participants were representative of diverse and key stakeholder groups and sectors in the region | alpha = .80 | No | |

| 61. Deverka, 2012 | Survey |

|

A online Likert‐scale for each component | 29 | Variety (Patients, consumers, healthcare providers, industry, purchasers and payers, and policymakers and regulators) | No | Yes | Engagement related to goal of establishing a stakeholder‐driven priority‐setting process for cancer genomics comparative effectiveness research in a clinical trials cooperative |

| 62. Khodyakov, 2012 | Survey | Community Engagement Research Index | List of 12 research activities that community partners participate in, (1 = “Community partners did not participate in this activity”; 2 = “Community partners consulted on this activity”; and 3 = “Community partners were actively engaged in this activity.”) | 12 | Community partners | No | No | |

| 63. Durrant, 2012 | Survey | Community involvement | "I help out in the community." And "I am an active member of a club or community organization." | 2 | pupils participating in the Youth Community Action pilot | factor analysis mention | No | |

| 64. Haga, 2013 | Survey | Positive feelings | Survey instrument with trust and worry items | 7 and 4 | Middle school students and their parents/guardians |

|

No | |

| 65. Henderson, 2013 | Survey | Preferences for knowledge exchange preferences for research collaboration perspectives on the proposed research agenda | Stakeholders knowledge exchange preferences, stakeholders research collaboration preferences, stakeholder research agenda perspectives | 3 | Multiple stakeholders primary sectors for survey respondents include: mental health, health, addictions, child welfare, education, justice, and others such as housing, shelters, outreach or employment services | No | No | |

| 66. Hoffman, 2010 | Survey | Community service questionnaire | Perceptions of the importance of community service activity and civic engagement. Likert‐based scale | 12 | Undergrad students from Metropolitan State University in St. Paul, MN | No | No | |

| 67. Human‐Vogel, 2012 | Survey | Community engagement | One overall scale with four subscales, each using five items to measure Satisfaction, Quality of alternatives mindfulness, and investment size | 30 | Midcourse undergraduates | alpha = 0.91 | Yes | Several aspects of commitment to Community engagement related to spending time with cultural groups other than their own. |

| 68. Jaskiewicz, 2013 | Intervention | Institutional recruitment scales |

|

3 | Community partners are municipal governments, nonprofit organizations and faith‐based institutions in addition to the corner stores they recruited | No | No | |

| 69. Kang, 2013 | Survey | Neighborhood belonging | The 4‐item subjective belonging index measuring feelings of attachment to a residential area. | 4 | 225 elders recruited from five elderly colleges in Daegu, S. Korea | alpha = .76 | Yes | Korean elders who used media frequently connected with local organizations, were actively involved in neighborhood activities and volunteering." |

| 69. Kang, 2013 | Survey | Perceived collective efficacy | Measure level of confidence regarding their neighbors' willingness to participate in neighborhood problem solving process | 3 | 225 elders recruited from five elderly colleges in Daegu, S. Korea | alpha = .76 | Yes | Korean elders who used media frequently connected with local organizations, and had conversations with neighbors often were actively involved in neighborhood activities and volunteering. |

| 69. Kang, 2013 | Survey | Volunteering | The degree to which respondents believed their neighbors would volunteer in the future based on past experiences. | 2 | 225 elders recruited from five elderly colleges in Daegu, S. Korea | alpha = .68 | Yes | Korean elders who volunteered with local organizations, and had conversations with neighbors were actively involved in neighborhood activities and volunteering. |

| 69. Kang, 2013 | Survey | Length of residence and homeownership | Indicate the number of years they had lived at their current residence | 1 | 225 elders recruited from five elderly colleges in Daegu, S. Korea | alpha = .84 | Yes | "Results found that Korean elders who used media frequently connected with local organizations, and had conversations with neighbors often were actively involved in neighborhood activities and volunteering." |

| 69. Kang, 2013 | Survey | Scope of connections to community organizations | Belonging to any of five different types of organizations: (1) sports or recreational, (2) religious, (3) neighborhood, (4) political, (5) other. | 1 | 225 elders recruited from five elderly colleges in Daegu, S. Korea | Alpha = .76 | Yes | "Results found that Korean elders who used media frequently connected with local organizations, and had conversations with neighbors often were actively involved in neighborhood activities and volunteering." |

| 70. Kazemipur, 2011 | Survey | Canadian General Social Survey | Self‐Interest Social Engagement, Cultural‐Community Participation, Political party activism, Political Information acquiring and sharing, Confidence in private institutions, Voting, Trust, Volunteering, Neighborliness, Group activity, Political expression, Social networks, Donation‐Youth‐Business, Confidence in public institution, Religion | 45 | General public, stakeholder in government | Factor analysis and alphas presented for 15 subscales | No | |

| 71. Krauss, 2012 | Survey | School engagement | 6‐item scale measuring the respondents' adherence to the education goals and values of their school. | 6 | 895 third year Muslim high school students from 19 schools throughout the Klang Valley (greater Kuala Lumpur region). | alpha = .74 | Yes | School engagement significantly predicted religiosity for the full sample of students from both types of families |

| 71. Krauss, 2012 | Survey | Mosque involvement | 6‐item scale measuring the respondents' adherence to the education goals and values of their school. | 2 | 895 third year Muslim high school students from 18 public secondary schools throughout the Klang Valley (greater Kuala Lumpur region). | No | Yes | Mosque involvement significantly predicted religiosity for the full sample of students from both types of families |

| 71. Krauss, 2012 | Survey | Youth organization involvement | 6‐item scale measuring the respondents' adherence to the education goals and values of their school. | 2 | 895 third year Muslim high school students from 18 public secondary schools throughout the Klang Valley (greater Kuala Lumpur region). | No | Yes | Youth organization involvement significantly predicted religiosity for the full sample of students from both types of families |

| 34. Kyle, 2010 | Survey | Community attachment scale | Items measured along 5‐point scale of 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. | 9 | Residents in Southern CA; primarily white, educated men | Alpha = .91 | Yes | Those most attached to their homes and community were more likely to report current use of the Firewise techniques and expressed greater likelihood of future use. Community attachment was more strongly predictive of community‐based activities. |

| 72. Lee, 2009 | Author report/literature review | Percent skilled attendance at birth | Meta‐analysis of community mobilization using 4 studies | 9 | Skilled birth attendant | No | Yes | There was evidence that community mobilization with high levels of community engagement can increase institutional births and reduce perinatal and early neonatal mortality. |

| 73. McComas, 2011 | Survey | Perceived fairness of university decision makers | Respondents were asked how respondents perceived university decision makers would behave toward them and their community. | 9 | Tompkins county property owners selected from property tax rolls | alpha = .93 | Yes | A significant positive relationship between fairness and support. |

| 74. Narsavage, 2003 | Survey | Effects of service learning | Quantitative pre and post‐testing. | 14 | Students from a service learning class | No | No | |

| 75. Nokes, 2005 | Intervention | Civic engagement | Attitudes toward community involvement, influence of the service learning experience on choice of major and profession, and personal reflections on the service learning experience | 12 | Nursing students | alpha = "acceptable" | Yes | Participants' civic engagement scores increased significantly after the intervention. |

| 76. Orians, 2009 | Survey | Characteristics of networks (assessed both before and after the implementation) | Participants rated several aspects of PACE involvement | 4 | Individuals in communities implementing PACE | No | No | The measures were outcomes of program implementation. |

| 77. Peterson, 2006 | Survey | Coalition structure and processes | Factors identified as important for community involvement. | Unclear | Members of Allies Against Asthma coalitions | No | No | |

| 78. Phillipson, 2012 | Survey | Perceived impact on the stakeholders policies or practices and knowledge or understanding | Response on 4 point scale | 1 | Multiple types of stakeholders in projects | No | Yes | A close relationship is found between mechanisms and approaches to knowledge exchange and the spread of benefits for researchers and stakeholders. |

| 78. Phillipson, 2012 | Survey | Perceived impact on research relevance and scientific quality | Response on a 5 point scale | 1 | Multiple types of stakeholders in projects | No | No | |

| 79. Puddifoot, 2003 | Survey | Twelve items measuring personal community identity and 12 items measuring general community identity | Personal view of the quality of community life and others view of community life | 24 | residents of defined community | No | No | |

| 80. Rawstorne, 2007 | Cohort study | Community engagement | Dependent variable; Whether or not participants felt they were part of a positive community. | 1 | People living with positive HIV diagnosis | No | Yes | Historical time of diagnosis and factors related to living with HIV help explain HIV‐positive community engagement. |

| 43. Rinner, 2009 | Survey | Assessment of the engagement experience | Participants were asked to rate six statements on a five‐point scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. | 7 | Residents within or near the 'Queen West Triangle' in Toronto | No | No | |

| 81. Rosenberger, 2014 | Survey | Community engagement | Which of gay or bisexual functions or activities they had participated in the city where they lived. | 18 | Coalition members affiliated with CTC | Alphas not less than .55 | No | |

| 82. Shapiro, 2013 | Survey | Goal‐directedness Efficiency Opportunity for participation Cohesion | Participant surveys | 17 | Coalition members affiliated with CTC | Factor analysis, with “reasonable” loadings | No | n/a |

| 83. Thompson, 2010 | Post‐test following a participatory planning workshop | Participants' perceived benefits of attending the workshops | New Ecological Paradigm Scale assessment and four questions. | Unclear | Scientists, decision makers and stakeholders | No | Yes | Participants gained a greater understanding of complexity and system dynamics related to urban air shed |

| 84. Tiernan, 2013 | Survey | Community Integration Measure |

|

10 | Older African Americans who participate in research | alpha = .83 | Yes | Community engagement significantly related to well‐being. |

| 48. Tiffany, 2012 | Intervention | Tiffany‐Eckenrode Program Participation Scale (TEPPS) | Measuring theoretically significant characteristics of program participation: Personal Development, Voice/Influence, Safety/Support, and Community Engagement | 21 | Adolescents engaged in after school activities in NYC | alpha = .90 | No |

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

We systematically reviewed the literature on existing measures of stakeholder engagement. We found a variety of measurements, with differing qualities and development trajectories. Some were simply counts of event attendance, while others were theoretically based and developed with sound psychometric principles and analyses. The variability in the process of identifying these measures listed in the articles found for this review was considerable, making grouped analysis difficult.

Many of these measures were participant head counts by researchers or participants themselves. As such, these do not really measure any sort of engagement directly. Therefore, we cannot tell if these measures actually assess engagement or some other cluster of factors that motivate people to attend events and activities. On the one hand, these counted types of measures are relatively easy to obtain and can be gathered from documents that already exist, such as meeting minutes or counts of attendees at events. Thus, they are an easy measure to gather and use, and are often presented without much extra work. But likely we need more data before considering that high attendance equates to high engagement in a process, particularly in light of potential confounders such as incentives for attendance. These types of data would be relatively easy to collect and produce, and this systematic review points to the need for these corroborating data. Also, there is no consensus in the literature on defining engagement, what kind of engagement is desired, and how involved a community member must be to be considered “engaged.” These are all likely context‐dependent, and therefore expectations of consensus are not relevant.

The participant‐reported measures of engagement are varied and diverse in their names, definitions, and purposes. Data on the psychometric properties of scales were generally lacking, although some investigators provided some limited data on scale performance, presented in Table 1. The scales measured a broad range of concepts, including motivations for participating, strength of relationship between researcher and community, comfort with community activities, and familiarity with community members. This breadth indicates that we need clearer definitions of the construct(s) involved in engagement before new development occurs. In most of the publications, the development process was not detailed and no plans were proposed to identify scale psychometric properties. This absence could pose a problem when comparing across multiple communities or when attempting to obtain a point estimate of engagement to better understand a research process or community or stakeholder's actual involvement, especially in large‐scale research efforts. Weiner and others have identified a similar lack in the implementation science literature as well,85 pointing to a potential challenge for new efforts, such as Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research Institute and the Precision Medicine Initiative.

LIMITATIONS OF THE PRESENT REVIEW

There were several choices that we made that limit the generalizability of the findings. First, we did not formally rate the quality of each measurement study. We found that our initial attempts to rate measurement quality resulted in low ratings, due to the absence of psychometric data. This is likely due to the early nature of this field, but future work will hopefully find improvements in the methodological development of measures for engagement. We did not review related constructs that could be used to assess some component of, or were related to, engagement, given the lack of definitional clarity and term usage across literatures. Therefore, we likely did not include measures that could have provided some information on this topic. Our focus on English‐language articles is a limitation of the data as presented; however, our assessment of the non‐English articles we were able to translate indicates that this did not seem to bias the review.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

What is the right kind of engagement measure to use? First, we clearly need to develop better scales that (1) use a theory or model, (2) provide psychometric data, (3) can be short and used with large‐scale projects, and (4) pick up the key elements of engagement that are critically important for involvement in health‐related projects. These are high standards indeed, but feasible. Some scales exist, but because relationships and purposes of engagement vary so widely, selecting the right scale for the situation will depend on context, goals, and relationship. It is possible that no single scale will likely meet every need. This ultimately is an empirical question.

Given the increasing interest among researchers and funders in improving health outcomes through engagement of diverse stakeholders (communities, groups, individuals) in health‐related research and programs, we recommend greater attention to developing good quality (validated, yet flexible) measures that can help us assess the level of engagement throughout an ongoing process, specific to varying types of engagement, and health outcomes related to the engagement process. Better measures would be particularly helpful in assessing engagement of diverse groups of stakeholders in a research project. When stakeholders can communicate their values in a research team, those values often influence the research process and can be an important source of new research questions, as well as a source of more accurate interpretations of the research findings.86

Some of the most interesting conceptual work is going on in qualitative projects. Qualitative data can accompany or inform quantitative approaches in mixed methods projects. For example, Schulz and colleagues10, 12 applied both qualitative and quantitative approaches to evaluate process and group dynamics in community‐based participatory research (CBPR) projects. Their evaluation addressed perceptions of openness, trust, and ownership, and informed an annual quantitative survey in which partnership members rated these aspects of group functioning. Questions such as one's “sense of ownership/belonging to the group” may be construed as measuring a deep level of engagement. More qualitative research can improve the field's understanding of how various stakeholders describe their expectations for levels of engagement and inform quantitative scales representing engagement in the words and thoughts of the original stakeholders. The volume of research in this area has increased over the last few years, so we are hopeful that we will see the development of high‐quality measures in these large studies.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Human Genome Research Institute P50 HG 3374.and K99HG007076

Conflict of Interest

No author reports having a conflict of interest with this work.

References

- 1. Concannon, T.W. , et al A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient centered outcomes research. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 12, 1692–1701 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2878-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fleurence, R.L. , et al Engaging patients and stakeholders in research proposal review: the patient‐centered outcomes research institute. Ann. Intern. Med. 161(2), 122–130 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lemke A.A. & Harris‐Wai J. Stakeholder engagement in policy development: challenges and opportunities for human genomics. Genet Med. 17(12):949–957 (2015. Dec). PMID: 25764215; PMCID: PMC4567945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kwan, B.M. , et al Stakeholder engagement in a patient‐reported outcomes (PRO) measure implementation: a report from the SAFTINet practice‐based research network (PBRN). J. Am. Board. Fam. Med. 29(1), 102–115 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Minkler, M. Ethical challenges for the “outside” researcher in community‐based participatory research. Health Educ., Behav. 31, 684 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Minkler, M.E. & Wallerstein, N.E. Community Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wallerstein, N. & Duran, B. Community‐based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am. J. Public Health 100(Suppl), S40–46 (2010). https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Butterfoss, F.D. & Francisco, V.T. Evaluating community partnerships and coalitions with practitioners in mind. Health Promot. Pract. 5, 108–114 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839903260844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Israel, B.A. Methods in Community‐Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schulz, A.J. , Israel, B.A. & Lantz, P. Instrument for evaluating dimensions of group dynamics within community‐based participatory research partnerships. Eval. Program Plan. 26, 249–262 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7189(03)00029-6. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lantz, P.M. , Viruell‐Fuentes, E. , Israel, B.A. , Softley, D. & Guzman, R. Can communities and academia work together on public health research? Evaluation results from a community‐based participatory research partnership in Detroit. J. Urban Health 78, 495–507 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/78.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Israel, B.A. , Schulz, A.J. , Parker, E.A. & Becker, A. Review of community‐based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 19, 173–202 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Khodyakov, D. , Stockdale, S. , Jones, A. , Mango, J. , Jones, F. & Lizaola, E. On measuring community participation in research. Health Educ. Behav. 40, 346–354 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198112459050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Francisco, V.T. , Paine, A.L. & Fawcett, S.B. A methodology for monitoring and evaluating community he alth coalitions. Health Educ. Res. 8, 403–416 (1993). https://doi.org/10.1093/her/8.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goodman, M.S. et al Evaluating community engagement in research: quantitative measure development. J. Commun. Psychol. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , Altman, D.G. & PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 62, 1006–1010 (2009. Oct). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. An, L.C. , et al Utilization of smoking cessation informational, interactive, and online community resources as predictors of abstinence: cohort study. J. Med. Internet Res. 10(5), e55, (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Andreae, S.J. , Halanych, J.H. , Cherrington, A. & Safford, M.M. Recruitment of a rural, southern, predominantly African‐American population into a diabetes self‐management trial. Contemp. Clin. Trials 33, 499–506 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2012.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Andrews, R , Cowell, R ., Downe, J. , Martin, S. & Turner, D. Supporting effective citizenship in local government: engaging, educating and empowering local citizens. Local Govern. Stud. 34, 489507 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1080/030039308022174 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ayuso, S. , Rodriguez, M.A. , Garcia, R. & Arino, M.A. Maximizing stakeholders’ interests: an empirical analysis of the stakeholder approach to corporate governance. IESE Business School Working Paper No. 670 (2007). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.982325

- 21. Clark, N.M. et al. Policy and system change and community coalitions: outcomes from allies against asthma. Am J. Public Health 100, 904‐912, (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fahrenwald, N.L. , Wey, B. , Martin, A. & Speceker, B.L. Community outreach and engagement to prepare for household recruitment of national children's study participants in a rural setting. J. Rural Health 29, 61–68 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.2012.00418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fothergill, K.E. , Ensminger, M.E. , Robertson, J. , Green, K.M. , Thorpe, R.J. & Juon, H. Effects of social integration on health: a prospective study of community engagement among African American women. Soc. Sci. Med. 72, 291–298 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.10.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Frew, P.M. , del Rio, C. , Clifton, S. , Archibald, M. , Hormes, J.T. & Mulligan, M.J. Factors influencing HIV vaccine community engagement in the urban south. J. Commun. Health 33, 259–269 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-008-9086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Frew, P.M. , Archibald, M. , Hixson, B. & del Rio, C. Socioecological influences on community involvement in HIV vaccine research. Vaccine 29, 6136–6143 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Galichet, B. et al Linking programmes and systems: lessons from the GAVI health systems strengthening window. Trop. Med. Int. Health 15, 208–215 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02441.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gregson, S. , Nyamukapa, C.A. , Sherr, L. , Mugurungi, O. & Campbell, C. Grassroots community organizations’ contribution to the scale‐up of HIV testing and counselling services in Zimbabwe. AIDS, 27 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283601b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hess, F.M. & Leal, D.L. The opportunity to engage: how race, class, and institutions structure access to educational deliberation. Educ. Policy 15, 474 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904801015003007 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hood, N.E. , Brewer, T. , Jackson, R. & Wewers, M.E. Survey of community engagement in NIH‐funded research. Clin. Transl. Sci. 3, 19–22 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-8062.2010.00179.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hughes, J. & Stone, W. Family change and community life: an empirical investigation of the decline thesis in Australia. J. Sociol. 42, 242 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1177/14407833060667 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jolibert, C. & Wesselink, A. Research impacts and the impact on research in biodiversity conservation: the influence of stakeholder engagement. Environ. Sci. Policy, 22, 100–111 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2012.06.012. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kagan, J.M. et al Community‐researcher partnerships at NIAID HIV/AIDS clinical trials sites: insights for evaluation and enhancement. Progr. Commun. Health Partner. Res. Educ. Action 6, 311–320 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2012.0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kamuya, D.M. , Marsh, V. , Kombe, F.K. , Geissler, W. & Molyneux, S.C. Engaging communities to strengthen research ethics in low‐income settings: selection and perceptions of members of a network of representatives in costal Kenya. Dev. World Bioethics 13, 10–20 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kyle, G.T. , Theodori, G.L. , Absher, J.D. & Jun, J. The influence of home and community attachment on firewise behavior. Soc. Nat. Resources 23, 1075–1092 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920902724974 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Litt, J.S. et al Active living collaboratives in the United States: understanding characteristics, activities, and achievement of environmental and policy change. Prevent. Chronic Dis. 10 (2013). https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd10.120162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McNaughton, D. The importance of long‐term social research in enabling participation and developing engagement strategies for new dengue control technologies. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6, 5 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.00017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nahar, T. et al Scaling up community mobilization through women's groups for maternal and neonatal health: experiences from rural Bangladesh. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 12 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. O'Brien, A. , Farrell, S.J. & Faulkner, S. Community treatment orders: beyond hospital utilization rates examining the association of community treatment orders with community engagement and supportive housing. Commun, Ment, Health 45, 415–419 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-009-9203-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Overstreet, S. , Devine, J. , Bevans, K. & Efreom, Y. Predicting Parental involvement in children's schooling within an economically disadvantaged African American sample. Psychol. Schools 42 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20028 [Google Scholar]

- 40. Phillips, G. et al Well London phase‐1: results among adults of a cluster‐randomized trial of a community engagement approach to improving health behaviors and mental well‐being in deprived inner‐city neighbourhoods. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 68, 606–614 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2013-202505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pitama, S. et al A Kaupapa Maori approach to a community cohort study of heath disease in New Zealand. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health, 35 249–255 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Polson, E. , Kim, Y. , Jang, S. , Johnson B. & Smith, B. Being prepared and staying connected: scouting's influence on social capital and community involvement. Soc. Sci. Q. 94 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12002 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rinner, C. & Bird, M. Evaluating community engagement through argumentation maps—a public participation GIS case study. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 36, 588–601 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1068/b34084 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rose, A. , Hennis, A.J. & Hambleton, I.R. Sex and the city: difference in disease‐ and disability‐free life years, and active community participation of elderly men and women in 7 cities in Latin America and the Caribbean. BMC Public Health 8 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-8-127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Saewyc, E.M. & Tonkin, R. Surveying adolescents: focusing on positive development. J. Pediatr. Child Health 13, 43–47 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shah, D. , Schmierbach, M. , Hawkins, J. , Espino R. & Donavan, J. Nonrecursive models of internet use and community engagement: questioning whether time spent online erodes social capital. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 79, 964–987 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sirin, S.R. & Katsiaficas, D. Religiosity, discrimination, and community engagement: gendered pathways of Muslim American emerging adults. Youth Soc. 43, 1528–1546 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X10388218 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tiffany, J.S. , Exner‐Cortens, D. & Eckenrode, J. A new measure for assessing youth program participation. J. Commun. Psychol. 40, 277–291 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Van Vorhees, B.W. et al Protective and vulnerability factors predicting new‐onset depressive episode in a representative of U.S. Adults. J. Adolesc. Health 42, 605–616 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.11.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Westfall, J.M. et al Engaging communities in education and research PBRNs, AHEC, and CTSA. Clin. Transl. Sci. 5, 250–258 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00389.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wilkins, C.H. et al Community representatives’ involvement in Clin. Transl. Sci. awardee activities. Clin. Transl. Sci. 6, 292–296 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.12072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Algesheimer, R. , Dholakia, U.M. & Herrmann, A. The social influence of brand community: evidence from European car clubs. J. Market. 69, 19–34 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 53. Brown, D.E. et al Graduate health professions education: an interdisciplinary university‐ community partnership model 1996‐2001. Educ. Health 16 176–188 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1080/1357628031000116826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bruning, S.D. , McGrew, S. & Cooper, M. Town‐gown relationships: exploring university‐community engagement from the perspective of community members. Public Relat. Rev. 32, 125–130 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2006.02.005 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chiu, C.H. Cynicism about community engagement in Hong Kong. Sociol. Spect. 25, 447–467, (2005).

- 56. Chung, B. et al Using community arts events to enhance collective efficacy and community engagement to address depression in an African American community. Am J. Public Health 99 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Beringer, C. , Jonas, D. & Gemunden, H.G. Establishing project portfolio management: an exploratory analysis of the influence of internal stakeholders’ interactions. Project Manag. J. 43, 16–32 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1002pmj.21307 [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cullier, D. Access attitudes: a social learning approach to examining community engagement and support for press access to government records. Journal. Mass Commun. Q. 85 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 59. Davis, A. , Mbete, B. , Fegan, G. , Molyneux, S. & Kinyanjui, S. Seeing ‘with my own eyes’: strengthening interactions between researchers and schools. IDS Bull. 43 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 60. De Freitas, D.M. , King, D. & Cottrell, A. Fits and misfits of linked public participation and spatial information in water quality management on the Great Barrier Reef coast (Australia). J. Coast. Conserv. 17, 253–269 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11852-011-0167-y [Google Scholar]

- 61. Deverka, P.A. et al Facilitating comparative effectiveness research in cancer genomics: evaluating stakeholder perceptions of the engagement process. J. Comp. Res. 1, 359–370 (2012). https://doi.org/10.2217/cer.12.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Khodyakov, D. , Stockdale, S. , Jones, A. , Mango, J. , Jones, F. & Lizaola, E. On measuring community participation in research. Health Educ. Behav. 40 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198112459050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Durrant, I. , Peterson, A. , Hoult, E. & Leith, L. Pupil and teacher perceptions of community action: an English context. Educ. Res. 54, 259–283 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2012.710087 [Google Scholar]

- 64. Haga, S.B. , Rosanbalm, K.D. , Boles, L. , Tindall, G.M. , Livingston, T.M. & O'Daniel, J.M. Promoting public awareness and engagement in genome sciences. J. Genet. Counsel. 22, 508–516 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-013-9577-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Henderson, J. , Brownlie, E. , Rosenkranz, S. , Chaim, G. & Beitchman, J. Integrated knowledge and grant development: addressing the research practice gap through stakeholder‐informed research. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 22, 268–274, (2013). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hoffman, A.J. , Wallach, J. & Sanchez, E. Community service work, civic engagement, and “giving back” to society: key factors in improving interethnic relationships and achieving “correctedness:” in ethnically diverse communities. Aust. Soc. Work 63, 418–430 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 67. Human‐Vogel, S. & Dippenaar, H. Exploring pre‐service student‐teachers commitment to community engagement in the second year of training. Higher Educ. Res. Dev. 32, 188–200 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.678307 [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jaskiewicz, L. , Dombrowski, R.D , Drummond, H.M. , Barnett, G.M. , Mason, M. & Welter, C. Partnering with community institutions to increase access to healthful foods across municipalities. Prevent. Chron. Dis. 10 (2013). https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd10.130011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kang, S. The elderly population and community engagement in the Republic of Korea: the role of community storytelling network. Asian J. Commun. 23, 302–321 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2012.725176 [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kazemipur, A. The community engagement of immigrants in host societies: the case of Canada. Int. Migrat. 50 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2010.00638.x [Google Scholar]

- 71. Krauss, S.E. et al Religious socialization among Malaysian Muslim adolescents: a family structure comparison. Rev. Relig. Res. 54, 499–518 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-012-0068-z [Google Scholar]

- 72. Lee, A.C. , et al Linking families and facilities for care at birth: what works to avert intrapartum‐related deaths? Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 107 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. McComas, K.A. , Stedman, R. & Hart, P.S. Community support for campus approaches to sustainable energy use: the role of “town‐gown” relationships. Energy Policy 39, 2310–2318 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.01.045 [Google Scholar]

- 74. Narsavage, G.L. , Batchelor, H. , Lindell, D. & Chen, Y. Developing personal and community learning in graduate nursing education. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 24 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Nokes, K.M. , Nickitas, D.M. , Keida, R. & Neville, S. Does service‐learning increase cultural competency, critical thinking, and civic engagement? J. Nurs. Educ. 44 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Orians, C. et al Strengthening the capacity of local health agencies through community‐based assessment and planning. Public Health Rep. 124, 875–882 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Peterson, J.W. et al. Engaging the community in coalition efforts to address childhood asthma. Health Promot. Pract. 7, 56s–65s, (2006). https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839906287067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Phillipson, J. , Lowe, P. , Procter, A. & Ruto, E. Stakeholder engagement and knowledge exchange in environmental research. J. Environ. Manag. 95, 56–65 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Puddifoot, J. Exploring “personal” and “shared” sense of community identity in Durham City, England. J. Commun. Psychol. 31, 87–106 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.10039 [Google Scholar]

- 80. Rawstorne, P. , Prestage, G. , Grierson, J. , Song, A. , Grulich, A. & Kippax, S. Trends and predictors of HIV‐positive community attachment among PLWHA. AIDS Care 17, 589–600 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1080/09540120412331299834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Rosenberger, J.G. , Schick, V. , Schnarrs, P. , Novak, D.S. & Reece, M. Sexual behaviors, sexual health practices and community engagement among gay and bisexually identified men living in rural areas of the United States. J. Homosex. 61, 1192–1207 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2014.872525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Shapiro, V.B. , Oesterle, S. , Abbot, R.D. , Arthur, M.W. & Hawkins, D. Measuring dimensions of coalition functioning for effective and participatory community practice. Social Work Res. 37 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svt02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Thompson, J. , Forster, C.B. , Werner, C. & Peterson, T.R. Mediated modeling: using collaborative processes to integrate scientist and stakeholder knowledge about greenhouse gas emissions in an urban ecosystem. Soc. Nat. Resourc. 23, 742–757 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920802102032 [Google Scholar]

- 84. Tiernan, C. , Lysack, C. , Neufeld, S. & Lichtenberg, P.A. Community engagement: an essential component of well‐being in older African‐American Adults. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 77, 233–257 (2013). http://doi.org/10.2190/AG.77.3.d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Lewis CC, Fischer S, Weiner BJ, Stanick C, Kim M & Martinez RG. Outcomes for implementation science: an enhanced systematic review of instruments using evidence‐based rating criteria. Implement. Sci 10, 155 (2015. Nov 4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kelley, M et al Values in translation: How asking the right questions can move translational science toward greater health impact, CTS 5, 445–451 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]