Abstract

Drug‐dose modification in chronic kidney disease (CKD) utilizes glomerular filtration rate (GFR) with the implicit assumption that multiple renal excretory processes decline in parallel as CKD progresses. We compiled published pharmacokinetic data to evaluate if GFR predicts renal clearance changes as a function of CKD severity. For each drug, we calculated ratio of renal clearance to filtration clearance (Rnf). Of 21 drugs with Rnf >0.74 in subjects with GFR >90 mL/min (implying filtration and secretion), 13 displayed significant change in Rnf vs. GFR (slope of linear regression statistically different from zero), which indicates failure of GFR to predict changes in secretory clearance. The dependence was positive (n = 3; group A) or negative (n = 10; group B). Eight drugs showed no correlation (group C). Investigated drugs were small molecules, mostly hydrophilic, and ionizable, with some characterized as renal transporter substrates. In conclusion, dosing adjustments in CKD require refinement; in addition to GFR, biomarkers of tubular function are needed for secreted drugs.

Study Highlights

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON THE TOPIC?

✓ Intact nephron hypothesis states that all renal excretory processes decline in parallel with CKD progression, which is an underlying assumption for drug dosage adjustments in CKD that are based on serum creatinine. Since its very introduction, the universal applicability of the hypothesis has been questioned.

WHAT QUESTION DID THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

✓ Can measures of glomerular filtration accurately predict alterations in drug renal clearance, inclusive of secretory clearance, across the range of CKD for all drugs? If not, what is the pattern and the degree of the observed disconnect between glomerular filtration and tubular secretion, and what are the potential clinical implications?

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS TO OUR KNOWLEDGE

✓ This is the first systematic analysis giving evidence that there is a distinct subset of drugs showing a disconnect between glomerular filtration and tubular secretion in CKD.

HOW THIS MIGHT CHANGE CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OR TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE

✓ Our data support a reconsideration of drug dosing adjustment strategies in CKD. Incorporating measurements of proximal tubule secretory function in renal dosing algorithms could refine renal drug dosing strategies, leading to more personalized use of medications in patients with kidney disease.

Clearance of drugs that mainly occurs via renal excretion is compromised in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). To avoid systemic drug accumulation and adverse events in this population, the dosage of renally eliminated drugs requires appropriate reduction. Despite the fact that renal clearance of many medications occurs via secretion by the proximal tubule of the kidneys, dosing adjustment in renal impairment has traditionally relied on serum creatinine as a biomarker of deteriorating renal function. Although a creatinine‐based approach has been successful for some drugs (e.g., with older antibiotics), universal applicability has been questioned,1, 2 with reports appearing as early as 1972 of dose adjustment failures (e.g., chlorpropamide3).

The estimation of drug renal clearance reduction using creatinine clearance is based on the “intact nephron hypothesis,” which proposes that all renal excretory processes (i.e., filtration, tubular secretion, and reabsorption) decline in parallel with disease progression.4, 5 Therefore, it is generally assumed that for a given decline in creatinine clearance in CKD, the decrease in renal clearance of a drug that is either extensively secreted and/or reabsorbed is reduced to approximately the same degree as one that is neither reabsorbed nor secreted.6 Thus far, no systematic investigation or analysis of this assumption has been reported.

There are several reasons to suspect that glomerular filtration and proximal tubule secretion may not decline in parallel among people who have CKD. First, “CKD” encompasses a wide range of kidney diseases that differentially impact the glomeruli, tubules, and renal interstitium. Second, proximal tubule secretion is an active, cell‐based process, whereas glomerular filtration is passive and primarily determined by size and charge selectivity of the basement membrane. Third, secretion is subject to inhibition by retained solutes and other medications, whereas filtration is generally impervious to the solute load.

The present literature analysis aims to evaluate whether creatinine clearance (or other measures of glomerular filtration) consistently and accurately predict alterations in renal clearance of a diverse panel of drugs in patients with mild to severe stages of CKD. The findings may reveal limitations of the current creatinine‐based approach to dosage prediction and point to the need for further investigation into factors that modulate renal tubular clearance in CKD, which, in turn, could lead to an improved strategy for a personalized drug dosing algorithms in patients with CKD.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Literature review

We created a list of drugs for which pharmacokinetics in renal impairment have previously been characterized. Data were collected from the University of Washington Drug Interaction Database (www.druginteractioninfo.org, accessed in January 2016) and PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed, accessed between August 2015 and February 2016). The PubMed searches were conducted with the following terms: drug name AND pharmacokinetics AND renal impairment. When published data were presented in the form of a graph, relevant portions of the data were extracted with Plot Digitizer 2.6.6 (www.plotdigitizer.sourceforge.net). Only reports showing drug renal clearance data from individual subjects over a range of glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and not receiving dialysis treatment were considered for our analysis (i.e., we did not consider reports showing only mean values of drug renal clearance, total (renal and non‐renal) drug clearance, or area under the curve (AUC) data for each stage of CKD). We included all studies irrespective of the chosen measure of GFR (estimated GFR by Cockcroft‐Gault or Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation, measured GFR based on creatinine, inulin, or 51Cr‐EDTA clearance). Publications reporting only drug renal clearance in healthy subjects and patients with severe renal impairment (i.e., abbreviated pharmacokinetic studies typically performed for new drug applications) were not considered. In order to account for changes in drug plasma protein binding, we collected information on plasma unbound fraction (fU) of the drugs on our list. The drug fU data were accepted either as mean fU values per CKD stage, or fU values obtained from healthy subjects with values ≥0.80. For the latter case, the same value is assumed to hold true in CKD, as plasma protein binding is expected to decrease; hence, only a negligible change in fU would occur, at a maximum of 20%. When not available in the original publication, the fU data were collected from DrugBank (www.drugbank.ca, accessed between August 2015 and February 2016) or, in the case of p‐aminohippuric acid (PAH), separate literature publications were located.7 For drugs that were included in the final analysis, additional information, such as interaction with renal transporters from reported in vitro and in vivo studies as well as relevant physicochemical characteristics (molecular weight, logP, and pKa), was collected from the University of Washington Drug Interaction Database, DrugBank, PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed between August 2015 and February 2016) and ChEMBL (accessed between August 2015 and January 2016).

Index for the contribution of nonfiltration processes to the overall renal drug clearance

Renal clearance (CL) of a drug is described by the following Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where represents filtration clearance of unbound drug, ClS represents secretory clearance, and represents the fraction of the filtered and secreted drug that is subsequently reabsorbed (via passive and active processes). We estimated filtration clearance of a drug by multiplying individual GFR by the average plasma unbound fraction appropriate for either healthy renal function or subject's stage of CKD. The ratio of divided by (renal clearance to filtration clearance (Rnf)) is defined as an index to indicate the impact of nonfiltration processes upon drug renal clearance (i.e., either dominance by secretion or reabsorption).

| (2) |

Eq. (2) shows that Rnf is a function of and Fr representing the discrete process of secretion and reabsorption, respectively. According to Eq. (2), when in healthy subjects, the drug undergoes net secretion; when in healthy subjects, the drug undergoes net reabsorption. Drugs that have a value of Rnf close to 1 may undergo glomerular filtration only, or are subjected to an opposing interplay between tubular secretion and reabsorption resulting in a net loss that is more reflective of glomerular filtration.

Our analysis was focused on alterations in the contribution of tubular secretion to renal clearance across the range of CKD; hence, we selected those drugs for which passive reabsorption along the renal tubule is likely to be negligible based upon their physicochemical characteristics (i.e., being highly ionized at the luminal filtrate pH). Accordingly, we confined our analysis to drugs with Rnf >0.74, a cutoff value set below unity to allow for the well‐recognized intersubject variability in GFR of healthy subjects with normal renal function (mean normal GFR of all studies = 128.6 mL/min with a corresponding coefficient of variation = 26%). Thus, Rnf > 0.74 assures the likelihood that we are dealing with drugs that exhibit negligible net reabsorption in renal tubule, thus avoiding its complication in data interpretation. In the absence of reabsorption (Fr = 0), Eq. (2) simplifies to:

| (3) |

Differential alterations in renal filtration and secretory processes in CKD

According to the intact nephron hypothesis, secretion and reabsorption processes of a drug decline in parallel with glomerular filtration in CKD; if so, Rnf should remain constant across the range of GFR. In contrast, any disproportionate decline in tubular secretion (or reabsorption) relative to glomerular filtration would result in changes in ratio across the range of GFR, which can be presented graphically by plotting Rnf as a function of GFR. When Rnf increases as GFR declines, secretion clearance declines more slowly than GFR (i.e., tubular secretion is better preserved than filtration as disease progresses). For the opposite scenario (i.e., when Rnf decreases as GFR declines), tubular secretion deteriorates more rapidly than GFR with advancing kidney disease.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in Microsoft Excel and R statistical software.8 A linear regression was used to assess a significant change in Rnf (outcome variable) across GFR (predictor variable) by estimating if the slope of regression coefficient statistically differs from zero. For each drug, the slope of the linear regression was estimated as a measure of the direction and steepness of the dependence. Based on the regression coefficients, we estimated a fold‐change in ratio when GFR decreases from 90 mL/min (value in healthy subjects) to 30 mL/min (CKD stage 3B, www2.kidney.org/professionals/KDOQI/guidelines_ckd/p4_class_g1.htm), which represents another quantitative measure of the average degree of dissociation in the decline in secretory clearance vs. that in GFR.

RESULTS

Relevant pharmacokinetic data on 27 drugs were found in the literature; in the majority of cases (44%), the GFR as an index of CKD progression was determined by the measuring 24‐h creatinine clearance. Limited data were available regarding changes of drug plasma protein binding in CKD, with mean fU values for each CKD stage available only for seven drugs. The rest of the drugs in the data set had negligible or low plasma protein binding, as reported in healthy subjects. In the original data set, the estimated Rnf in healthy subjects ranged from 28.4 (olmesartan) to 0.11 (lacosamide). A large span in ratio indicates a diverse data set of solutes with respect to their renal handling, incorporating drugs that, in addition to glomerular filtration, either predominantly undergoes proximal tubule secretion, tubular reabsorption, or a mix of both processes.

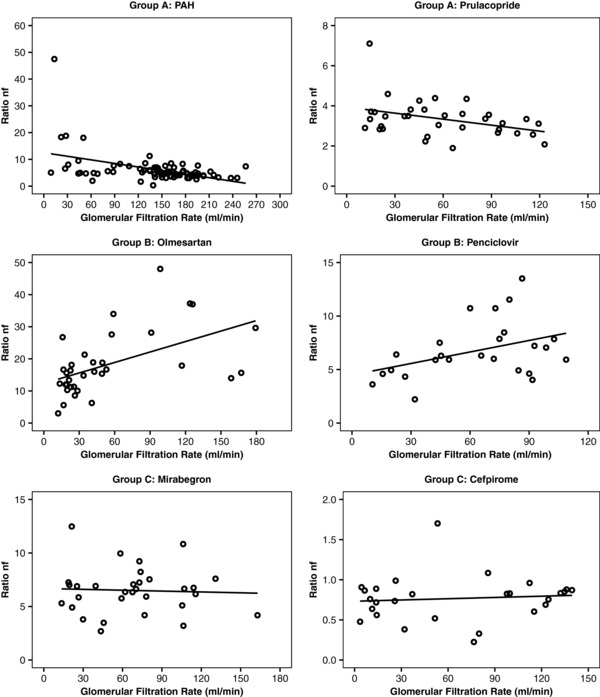

Of the original data set, 21 drugs had an estimated Rnf >0.74 that indicates minimal or absence of tubular reabsorption; a summary of the relevant parameters for this subset of drugs is presented in Table 1.9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 Graphical displays of Rnf as a function of GFR for all 21 drugs can be found in Supplementary Figures 1–4. Linear regression analysis showed that 13 drugs (62%) displayed statistically significant change in Rnf (outcome variable) across GFR (predictor variable), as defined by the slope of linear regression being statistically different from zero. Thus, the relationship between overall drug renal clearance to filtration clearance did not remain constant with disease progression. We further divided drugs in Table 1, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 into the three following groups; group A: significant increase in Rnf as GFR declines with disease progression; group B: significant decrease in Rnf as GFR declines; group C: no change in Rnf across the range of CKD. Typical examples of the Rnf vs. GFR plots for each of the three classes are shown in Figure 1. For all three drugs in group A, an increase in ratio represents a less than proportional decline in drug renal clearance (presumably reflective of secretory clearance) as compared with filtration clearance, indicating preservation of secretory component of renal clearance at later stages of CKD. The GFR significantly underpredicted renal clearance by an average of 20–32% in moderately impaired patients with CKD (CKD stage 3B). Notably, one of the drugs/solutes that showed such behavior is PAH, a marker of renal plasma flow. Among 10 drugs in group B, some have previously been cited as being extensively secreted via the proximal tubule, such as olmesartan, penciclovir, and metformin. A significant decrease in the Rnf as GFR declines for drugs in group B indicates a more pronounced decline of drug renal clearance or secretory clearance than GFR. Specifically, the GFR significantly overpredicted renal clearance, on average, by 22–48% in moderately impaired patients with CKD (CKD stage 3B). For drugs in both group A and group B, the most pronounced change in Rnf is observed at severe stages of CKD (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). For example, the absolute value of Rnf for olmesartan decreased from 22.1 in healthy subjects to 15.6 in CKD stage 3B (Figure 1). Eight drugs that did not display statistically significant correlation indicating no change in Rnf as CKD progresses, were assigned to group C. The Rnf in healthy subjects seems to follow a systematic trend across the three groups; group A had the highest median value of 3.89 (range, 5.32–2.79), followed by group B with median value of 1.86 (range, 28.4–0.79), and last group C with a median value of 1.55 (range, 16.30–0.81). Some of the drugs from groups A, B, and C are known to be substrates for (multiple) renal transporters.

Table 1.

Drugs with Rnf >0.74, listed in descending order according to the average ratio in healthy subjects (GFR ≥90 mL/min)

| Drug | Ref. | GFR method | Fraction unbound | Correlation coefficient | Regression slope (95% CI, min/mL) a | P value | Mean ratio at GFR ≥90 mL/min | Fold change in ratio b | Renal transporters c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A: Increase in ratio across the range of CKD | |||||||||

| PAH | 9 | Measured inulin or 51Cr‐EDTA CL | 0.88 | −0.4539 | −0.045 (−0.065, −0.025) | <0.001 | 5.32 | 1.32 | OAT1, OAT2, OAT3, MRP2, MRP4 |

| Dexpramipexole | 10 | eGFR by MDRD | 0.95 | −0.3785 | −0.019 (−0.037, −0.001) | 0.039 | 3.89 | 1.28 | OCT2 |

| Prulacopride | 11 | N/A | Mean fU / CKD stage | −0.3769 | −0.010 (−0.019, −0.001) | 0.028 | 2.79 | 1.20 | P‐gp |

| Group B: Decrease in ratio across the range of CKD | |||||||||

| Olmesartan | 12 | N/A | Mean fU / CKD stage | 0.5239 | 0.109 (0.045, 0.172) | 0.001 | 28.44 | 0.71 | OAT1, OAT3, OAT4, MRP2, MRP4 |

| Penciclovir | 13 | eGFR by C‐G | 0.80 | 0.4020 | 0.036 (0.001, 0.071) | 0.046 | 6.12 | 0.72 | OAT2 |

| Metformin | 14, 15, 16 | Measured CrCl or N/A | 1 | 0.3707 | 0.012 (0.001, 0.024) | 0.04 | 3.75 | 0.78 | OCT2, MATE1, MATE2K |

| Lenalidomide | 17 | Measured CrCl | Mean fU / CKD stage | 0.5731 | 0.019 (0.007, 0.031) | 0.004 | 3.30 | 0.61 | P‐gp |

| 5‐HMT | 18 | Measured CrCl | Mean fU / CKD stage | 0.4605 | 0.012 (0.003, 0.021) | 0.009 | 2.38 | 0.66 | P‐gp |

| Foscarnet | 19 | Measured CrCl | 0.83 | 0.4737 | 0.005 (0.001, 0.010) | 0.022 | 1.33 | 0.75 | N/A |

| Ribavirin | 20 | Measured CrCl | 1 | 0.5768 | 0.004 (0.0005, 0.008) | 0.031 | 0.94 | 0.69 | CNT2, CNT3, ENT1 |

| (S)‐Vigabatrin | 21 | Measured CrCl | 1 | 0.7571 | 0.373 (0.231, 0.515)d | <0.001 | 0.81 | 0.52 | N/A |

| Dabigatran | 22 | Measured CrCl | Mean fU / CKD stage | 0.4459 | 0.003 (0.001, 0.005) | 0.017 | 0.79 | 0.78 | P‐gp |

| Ceftobiprole | 23 | N/A | 0.84 | 0.9029 | 0.005 (0.004, 0.006) | <0.001 | 0.79 | 0.63 | OAT1, OCT2 |

| Group C: No change in ratio across the range of CKD | |||||||||

| Tiotropium | 24 | Measured CrCl | Mean fU / CKD stage | 0.4429 | 0.052 (–0.0001, 0.1045) | 0.05 | 16.30 | 0.79 | OCT2, OCTN1, OCTN2 |

| Pravastatin | 25 | Measured CrCl | Mean fU / CKD stage | 0.3828 | 0.052 (–0.023, 0.126) | 0.16 | 13.63 | 0.73 | OAT3, OAT4, BCRP, MRP2 |

| Mirabegron | 26 | eGFR by MDRD | N/A, measured Clu | −0.0469 | −0.003 (–0.024, 0.019) | 0.80 | 6.31 | 1.03 | P‐gp |

| Oseltamivir carboxylate | 27 | N/A | 0.97 | 0.4268 | 0.003 (–0.0004, 0.006) | 0.088 | 2.00 | 0.91 | OAT1, OAT3, MRP4 |

| Lomefloxacin | 28 | N/A | 0.90 | 0.157 | 0.001 (–0.003, 0.005) | 0.47 | 1.55 | 0.94 | OAT, OATP1A2 |

| Cidofovir | 29 | Measured CrCl | 0.94 | 0.1104 | 0.001 (–0.003, 0.004) | 0.707 | 0.94 | 0.96 | OAT1, OAT3 |

| Naloxegol | 30 | eGFR by MDRD | 0.96 | −0.2513 | −0.004 (–0.012, 0.003) | 0.236 | 0.92 | 1.27 | P‐gp |

| Cefpirome | 31 | Measured CrCl | 0.90 | 0.0933 | 0.001 (–0.002, 0.003) | 0.643 | 0.81 | 0.96 | N/A |

CI, confidence interval; C‐G, Cockcroft‐Gault; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CL, clearance; Clu, unbound clearance; CrCl, creatinine clearance; eGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; fU, unbound fraction; GFR, growth factor receptor; MDRD, Modification of Diet in Renal Disease; N/A, not available; OAT, organic anion transporters; OCT2, octamer‐binding transcription factor 2; PAH, p‐aminohippuric acid; P‐gp, P‐glycoprotein; Ref., reference; Rnf, ratio of renal clearance to filtration clearance.

aLinear regression slope is estimated for GFR as independent, and ratio as dependent variable. bFold change in ratio represents change in ratio when GFR drops from 90 mL/min (healthy subjects) to 30 mL/min (CKD stage 3B). cDrug has previously been characterized either in vitro and/or in vivo as a substrate for renal transporters. d(S)‐Vigabatrin regression coefficient units are min*kg/mL.

Figure 1.

Scatterplots of renal clearance to filtration clearance (Rnf) and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) in group A, group B, and group C drugs indicating that the ratio of Rnf does not necessarily remain constant with disease progression. Group A shows a significant increase in Rnf as GFR declines with disease progression; group B shows a significant decrease in Rnf as GFR declines; and group C shows no change in Rnf across the range of chronic kidney disease severity. Methods for GFR determination are listed in Table 2.

Table 2, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 shows six drugs that had an estimated ratio in healthy subjects ≤0.74 (i.e., tubular reabsorption is quite evident). All these drugs failed to show statistically significant deviation of regression slope from zero, implying that passive reabsorption declines in parallel with GFR. For all the drugs in Table 2,32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 information on their interactions with renal transporters (i.e., whether they are substrates and/or inhibitors) are either unavailable or incomplete. It is notable that fluconazole has been used as a marker of passive distal tubular reabsorption.1

Table 2.

Drugs with Rnf ≤0.74, listed in descending order according to the average ratio in healthy subjects (GFR ≥90 mL/min)

| Drug | Ref. | GFR method | Fraction unbound | Correlation coefficient | Slope of linear regression (95% CI, min/mL) a | P value | Ratio when GFR ≥90 mL/min | Fold change in ratio b | Substrate for renal transporters c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cefsulodin | 32 | Measured CrCl | 0.85 | −0.31 | −0.002 (−0.007, 0.002) | 0.275 | 0.67 | 1.18 | N/A |

| Pregabalin | 33 | eGFR by C‐G | 1 | 0.24 | 0.001 (−0.001, 0.003) | 0.240 | 0.57 | 0.85 | OCT2, OCTN1 |

| Nicotine | 34 | Measured 51Cr‐EDTA Cl | 0.95 | −0.31 | −0.003 (−0.007, 0.001) | 0.189 | 0.55 | 1.27 | OCT2 |

| Levetiracetam | 35 | N/A | 0.90 | −0.21 | −0.001 (−0.003, 0.001) | 0.348 | 0.30 | 1.20 | N/A |

| Fluconazole | 36 | Measured CrCl | 0.87 | −0.31 | −0.001 (−0.002, 0.001) | 0.265 | 0.20 | 1.18 | N/A |

| Lacosamide | 37 | eGFR by C‐G | 0.85 | −0.14 | −0.0002 (−0.001, 0.0004) | 0.443 | 0.12 | 1.10 | N/A |

CI, confidence interval; C‐G, Cockcroft‐Gault; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CL, clearance; CrCl, creatinine clearance; eGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; fU, unbound fraction; GFR, growth factor receptor; N/A, not available; OCT2, octamer‐binding transcription factor 2; Ref., reference; Rnf, ratio of renal clearance to filtration clearance.

aLinear regression slope is estimated for GFR as independent, and ratio as dependent variable. bFold change in ratio represents change in ratio when GFR drops from 90 mL/min (healthy subjects) to 30 mL/min (CKD stage 3B). cDrug has previously been characterized either in vitro and/or in vivo as a substrate for renal transporters.

We compiled the physicochemical characteristics of the 27 drugs in Table 3, specifically their molecular weight, lipophilicity (LogP), ionization (pKa), and charge at physiologic pH. These characteristics should govern the extent of drug passive reabsorption at distal parts of the nephron. All investigated drugs were small molecules with molecular weights up to 650 g/mol (naloxegol having the highest), mainly hydrophilic, as indicated by most LogP being below 1 to 2 (with just a few exceptions (e.g., olmesartan, mirabegron, and 5‐HMT), and contain more than one weakly acidic or basic functional groups, generating multiple pKa values. The majority of the drugs that are neutral at physiologic pH were shown to have an estimated Rnf in healthy ≤0.74 (i.e., drugs in Table 2, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37), which suggests passive reabsorption to be an important process in their renal excretion.

Table 3.

Physicochemical properties of drugs

| Drug | Molecular weight (g/mol) | LogP | pKa | Charge at physiologic pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAH | 194.19 | −1 | 2.7, 4.24 | Anion |

| Dexpramipexole | 211.33 | 1.9 | 9.47 | Cation |

| Prulacopride | 367.87 | 0.74 | 8.98, 14.64 | Cation |

| Olmesartan | 446.50 | 5.9 | 0.91, 4.96, 5.57, 13.93 | Anion |

| Metformin | 129.16 | −0.5 | 12.4 | Cation |

| Penciclovir | 253.26 | −1.5 | 2.84, 8.01 | Anion |

| Lenalidomide | 259.26 | −0.4 | 2.31, 11.61 | Neutral |

| 5‐HMT | 341.50 | 4.40 | N/A | N/A |

| Vigabatrin | 129.16 | −2.1 | 4.61, 9.91 | Zwitterion |

| Foscarnet | 126.00 | −2.1 | 3.13 | Anion |

| Ribavirin | 244.20 | −2.8 | −1.2, 11.88 | Neutral |

| Dabigatran | 627.73 | 3.8 | 3.87, 17.89 | Zwitterion |

| Ceftobiprole | 534.57 | −4.8 | 3.28, 10.33 | Zwitterion |

| Tiotropium | 392.51 | −1.8 | −4.3, 10.35 | Neutral |

| Pravastatin | 424.53 | 1.65 | −2.7, 4.21 | Anion |

| Mirabegron | 396.51 | 2.9 | 9.62, 13.84 | Cation |

| Oseltamivir carboxylate | 284.40 | 0.74 | 4.13, 9.26 | Zwitterion |

| Lomefloxacin | 351.35 | −0.3 | 5.64, 8.7 | Zwitterion |

| Cidofovir | 279.19 | −3.9 | 1.19, 2.15 | Anion |

| Naloxegol | 651.79 | −1 | 10.14, 12.2 | Cation |

| Cefpirome | 514.58 | 0.9 | 1.7, 2.43 | Anion |

| Cefsulodin | 532.55 | 0.2 | 0.29 | Anion |

| Nicotine | 162.23 | 1.17 | 8.5 | Neutral |

| Pregabalin | 159.23 | −1.3 | 4.8, 10.23 | Zwitterion |

| Levetiracetam | 170.21 | −0.6 | −1, 16.09 | Neutral |

| Fluconazole | 306.27 | 0.4 | 2.56, 12.71 | Neutral |

| Lacosamide | 250.29 | −0.022 | −1.5, 12.47 | Neutral |

N/A, not available; PAH, p‐aminohippuric acid.

DISCUSSION

Prediction of drug renal clearance according to either measured or estimated creatinine clearance has been the standard approach to drug dosage adjustment in CKD since its introduction by Lucius Dettli and Roger Jellife in the late 1960s.5, 38, 39, 40, 41 They invoked the intact nephron hypothesis proposed by Bricker4 and Bricker et al.42 nearly a decade earlier as the basis for the linear relationship between drug renal clearance and creatinine clearance as a measure of GFR. In this particular context, the intact nephron hypothesis has at times been misrepresented to portray nephrons in the pathological kidneys as being either untouched by disease or totally destroyed.

The intact nephron hypothesis was an attempt to explain the remarkable ability of patients with moderate to severe stage of CKD and substantive reduction in GFR to continue to excrete average dietary loads of water, nitrogenous wastes, and mineral solutes. In fact, the central idea of Bricker's hypothesis was adaptation of the residual nephrons to compensate for the loss of nephrons that succumbed to the disease process. Studies at the time showed that despite a widened range of single nephron GFR in the diseased kidneys, due to compromised functioning in some and hyperfunctioning in other remnant nephrons, glomerular and tubule function remain closely integrated as in normal kidneys. The close connection of glomerular and tubular functions is compatible with the general physiological importance of maintaining whole‐body fluid and electrolyte homeostasis in the setting of kidney injury. However, in retrospect, the idealized theoretical model of coupled glomerular and tubular loss is incompatible with the marked pathological heterogeneity of the disease processes that encompass the term “CKD.” For example, polycystic kidney disease, the most common genetic kidney disease, is characterized by aberrant cyst growth originating within distal and proximal tubule cells. The loss of glomerular function, evidenced by a decline in GFR, occurs late in the course of this disease, after most of the renal interstitium has been replaced by pathological cysts. On the other hand, diabetic nephropathy, the most common acquired kidney disease, is characterized by mesangial expansion and podocyte loss within the glomerulus that manifest clinically as albuminuria long before changes in GFR are detected. Moreover, the physiological process of secreting medications via the proximal tubule, an active process, differs diametrically from that of glomerular filtration, which is passive. Proximal tubule secretion of organic anions and cations occurs through a series or orchestrated steps that include transporter‐mediated uptake at the basolateral membrane, cellular internalization, and efflux transport into the tubular lumen. These active and regulated cellular processes are affected by a wide range of conditions within the kidneys, including oxygenation status, neuroendocrine signaling, and the water and electrolyte composition of the urinary filtrate. In contrast, glomerular filtration is a passive process that is primarily determined by size and charge selectivity of the basement membrane and by the cellular structures that constitute this barrier (i.e., podocytes and endothelial cells). These distinctions provide compelling rationales to investigate the assumption of GFR as a valid proxy of renal drug clearance when proximal tubule secretion is the predominant mechanism.

It is the concept of “homogeneity of glomerulotubular balance” that Dettli pointed to as support for assuming parallel decline in drug filtration and secretory clearance during renal impairment. Although the preservation of glomerulotubular balance for essential physiological solutes (e.g., sodium, potassium, and phosphate) has been thoroughly investigated by micropuncture studies in various experimental models of renal dysfunction,43 comparable studies with drug solutes (i.e., exogenous organic anions or cations) are notably absent. Dettli's creatinine‐based approach in prediction of drug renal clearance (i.e., the assumption of parallel decline in filtration and secretory clearance) in CKD has long been accepted based upon its empirical success with many older antibiotics,5 the majority of them having drug renal clearance that are close to GFR indicating minimal if not the absence of tubular secretion.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic literature analysis for drugs with renal clearance in CKD that cannot be accurately described by estimated or measured glomerular filtration function. Among 27 drugs and solutes for which data were available, we demonstrated failure of GFR measure to accurately predict alterations in drug renal clearance in CKD for 13 drugs (48%). Notably, based on their initial ratio Rnf index in healthy subjects, these drugs were primarily secreted in the proximal tubule in addition to being filtered through the glomerulus. The observed disconnect between glomerular filtration and overall drug renal clearance (more specifically secretory clearance) is most apparent in CKD stages 4 and 5. Furthermore, for 10 of 13 drugs (group B), the secretory component of drug renal clearance declines more rapidly than filtration clearance, resulting in an overprediction of renal drug clearance based upon estimated or measured GFR. The latter finding has clinical implications in that, for drugs in group B, the measure of residual GFR function alone cannot estimate the full extent of reduction in drug renal clearance during mid to late stages of disease, which potentially could lead to risks of overdosing and adverse drug events. Thus, we hypothesize that dosing of such drugs in the growing population with CKD would be improved if it is based on measures of both glomerular filtration and tubular secretion function. A small number of drugs fall into group A, which show a lesser reduction in renal drug clearance relative to GFR during progressive deterioration in kidney function. This could be interpreted as a sign of some sort of compensatory mechanism(s) within the proximal tubule to preserve secretory function in the face of a falling GFR. Until we fully understand the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the contrasting behavior of renal tubular secretion for the drugs in group A vs. group B, we have no a priori way of predicting how a highly renally secreted drug would behave in CKD.

One difficulty we encountered during the literature search was the inconsistency in reporting of data on pharmacokinetics in renal impairment. Investigations often focused on estimating the effects of renal impairment on overall drug exposure (reported either as changes in AUC, or changes in oral clearance) rather than effects of renal impairment on the more relevant measure of drug renal clearance. Furthermore, abbreviated pharmacokinetic studies in renal impairment, often performed as a special population study for a new drug application, only show changes in pharmacokinetics in severe renal impairment (CKD stage 4). Although these studies can be informative on the “worst case scenario” for changes in drug exposure and pharmacokinetic parameters, they do not provide detailed information regarding the course of decline in renal clearance processes during progressive stages of CKD. It should also be pointed out that publications tended to present group mean data for each stage of CKD, which deprives other investigators the opportunity for critical retrospective examination of individual patient data. It was challenging to find publications that contained sufficient information for our analysis. In light of our experience, we strongly recommend a concerted effort for the research community and regulatory agencies to develop a consensus on the essential parameters that should be collected in pharmacokinetic studies on renal impairment, namely renal clearance, plasma unbound fraction, and preferably inulin/iohexol/iothalamate clearance as a measure of actual GFR rather than the usual clinical measurement of creatinine clearance. Creatinine clearance is known to overestimate GFR due to its tubular secretion, which whereas minimal in the healthy state becomes evident as GFR is lowered during renal dysfunction.44

What does currently available literature say about the interdependence or lack thereof between glomerular and tubular function during the progression of disease? Our group has recently shown substantial interindividual variation in relationship between filtration and secretion (defined by creatinine and urea clearance estimated from the same timed urine collection) for an organic anion transporter substrate hippuric acid (ρ = 0.42).45 The mechanisms accounting for the discordance between tubular secretion and GFR deserve careful investigation. One important consideration is the marked difference in the amount of medication delivered to the kidneys via glomerular and proximal tubule processes. Glomerular filtration is limited to ∼20% of renal plasma flow and tightly regulated by afferent and efferent arteriolar tone. The proximal tubules receive the remaining 80% of renal plasma flow, enabling the possibility of near complete clearance of solute and medications in a single pass within the kidneys. A second important consideration is competition among retained substances and drugs for proximal tubule transporters. In vitro studies have demonstrated that some prominent uremic solutes, including hippuric acid, indoxyl sulfate, and p‐cresol sulfate inhibit basolateral organic anion transporters (OAT),46 and may further interact with apical efflux transporters (MATE1/2K, MRP2/4, and P‐glycoprotein (P‐gp)). In moderate to severe stages of CKD, these uremic solutes circulate at concentrations high enough to inhibit tubular drug transport.46, 47 Thus, uremic solute interference may explain the observed decrease in Rnf as GFR declines for group B drugs. A third consideration is the binding and debinding kinetics of specific medications for circulating proteins, such as albumin, which could affect the rate of proximal tubule secretion via competition for transporters at the basolateral aspect of the tubular epithelium. In contrast, the impact of protein binding on glomerular filtration is more of an equilibrium phenomenon that is readily predictable by ex vivo plasma unbound or free fraction, and by size and charge characteristics of the basement membrane.

An important limitation to our analysis is the likelihood of measurement error in the estimation of GFR. Different GFR estimation methods are more or less precise, and the accuracy varies over the range of renal function. Measurement error, however, would probably have introduced nondifferential misclassification, and the implications for the results of this error would have been to bias the estimates toward the null. We also included publications that displayed the individual patient data across the entire continuum of GFR, with some offering a rich data set (e.g., PAH; Figure 1), whereas others had rather sparse data (n ∼4 subjects) for some CKD stages (e.g., pravastatin, Supplementary Figure S3). It is possible that our test of statistical significance on the dependence of Rnf on GFR and the resulting assignment of the drugs to group C rather to groups A or B may be biased by the sample size and outliers. Notably, pravastatin was assigned to group C; it shows almost eightfold decrease in ratio across the full range of GFR, yet the correlation between ratio and GFR measure failed a test of statistical significance. For sure, further in vivo studies are necessary to better define pravastatin's renal handling in CKD (i.e., significant decrease in Rnf – group B vs. no change in Rnf – group C).

In conclusion, we contend that effective dosing of secreted drugs in patients with CKD requires a fundamental shift in our conceptualization of how the disease modulates renal drug clearance by extending our focus beyond filtration to include measures of renal tubular secretion. This will necessarily lead to re‐evaluation of current approaches to drug dosing adjustment in CKD from creatinine‐based methods to a more comprehensive approach of encompassing tubular markers that reflect the ongoing interference or pathophysiology of tubular drug transport function.48, 49, 50 The successful development of dosing algorithms that incorporate measures of proximal tubular function would refine and advance renal drug dosing strategies, leading to safer and more efficacious use of medications in patients with CKD. Additionally, understanding the relative contributions of filtration and secretion to drug renal clearance in the disease population would facilitate the necessary task of in vitro‐to‐in vivo scaling during the transition of a drug candidate from the preclinical phase to phase I and II clinical trials in new drug development.

Supporting information

Drugs and solutes with a ratio greater than 0.74 and showing increase in ratio across the range of CKD (Group A).

Drugs and solutes with a ratio greater than 0.74 showing decrease in ratio across the range of CKD (Group B).

Drugs and solutes with a ratio greater than 0.74 showing decrease in ratio across the range of CKD (Group B).

Drugs and solutes with a ratio greater than 0.74 showing no statistically significant correlation (no change in ratio) across the range of CKD (Group C).

Drugs and solutes with a ratio greater than 0.74 showing no statistically significant correlation (no change in ratio) across the range of CKD (Group C).

Drugs and solutes with a ratio less than or equal to 0.74 showing no statistically significant correlation (no change in ratio) across the range of CKD.

Supplemental Information

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by grants from the National Institute of Health NCATS Grant KL2 TR000421 and R01GM121354, the Norman S. Coplon Extramural Grant Program by Satellite Healthcare, a not‐for‐profit renal care provider, and an unrestricted gift from the Northwest Kidney Centers to the Kidney Research Institute. A.C. was a recipient of the Warren G. Magnuson Scholarship and the Elmer M. Plein Endowed Research Fund at the University of Washington.

Author Contributions

C.K.Y., A.C., D.D.S., B.R.K., C.R.‐C., and J.H. wrote the manuscript. C.K.Y., A.C., D.D.S., and J.H. designed the research. C.K.Y. and A.C. performed the research. C.K.Y., A.C., and C.R.‐C. analyzed the data.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1. Putt, T.L. , Duffull, S.B. , Schollum, J.B. & Walker, R.J. GFR may not accurately predict aspects of proximal tubule drug handling. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 70, 1221–1226 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tett, S.E. , Kirkpatrick, C.M. , Gross, A.S. & McLachlan, A.J. Principles and clinical application of assessing alterations in renal elimination pathways. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 42, 1193–1211 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Petitpierre, B. , Perrin, L. , Rudhardt, M. , Herrera, A. & Fabre, J. Behaviour of chlorpropamide in renal insufficiency and under the effect of associated drug therapy. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 6, 120–124 (1972). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bricker, N.S. On the meaning of the intact nephron hypothesis. Am. J. Med. 46, 1–11 (1969). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dettli, L. Drug dosage in renal disease. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1, 126–134 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tozer, T.N. , Rowland, M. & Rowland, M. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: concepts and applications. 4th edn. (Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott William & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maher, F.T. , Strong, C.G. & Elveback, L.R. Renal extraction ratios and plasma‐binding studies of radioiodinated o‐iodohippurate p‐aminohippurate in man. Mayo Clin. Proc. 46, 189–192 (1971). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Core Team R. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: http://www.R-project.org(2015). [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clericetti, N. & Beretta‐Piccoli, C. Lithium clearance in patients with chronic renal diseases. Clin. Nephrol. 36, 281–289 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. He, P. et al Pharmacokinetics of renally excreted drug dexpramipexole in subjects with impaired renal function. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 54, 1383–1390 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Smith, W.B. , Mannaert, E. , Verhaeghe, T. , Kerstens, R. , Vandeplassche, L. & Van de Velde, V. Effect of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of prucalopride: a single‐dose open‐label phase I study. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 6, 407–415 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. von Bergmann, K. , Laeis, P. , Püchler, K. , Sudhop, T. , Schwocho, L.R. & Gonzalez, L. Olmesartan medoxomil: influence of age, renal and hepatic function on the pharmacokinetics of olmesartan medoxomil. J. Hypertens. Suppl. 19, S33–S40 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Boike, S.C. et al Pharmacokinetics of famciclovir in subjects with varying degrees of renal impairment. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 55, 418–426 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Noel, M. Kinetic study of normal and sustained release dosage forms of metformin in normal subjects. Res. Clin. Forums 1, 33–44 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tucker, G.T. , Casey, C. , Phillips, P.J. , Connor, H. , Ward, J.D. & Woods, H.F. Metformin kinetics in healthy subjects and in patients with diabetes mellitus. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 12, 235–246 (1981). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sirtori, C.R. et al Disposition of metformin (N,N‐dimethylbiguanide) in man. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 24, 683–693 (1978). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen, N. et al Pharmacokinetics of lenalidomide in subjects with various degrees of renal impairment and in subjects on hemodialysis. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 47, 1466–1475 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Malhotra, B. , Gandelman, K. , Sachse, R. & Wood, N. Assessment of the effects of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetic profile of fesoterodine. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 49, 477–482 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aweeka, F.T. et al Effect of renal disease and hemodialysis on foscarnet pharmacokinetics and dosing recommendations. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. Hum. Retrovirol. 20, 350–357 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. K Gupta, S. , Kantesaria, B. & Glue, P. Exploring the influence of renal dysfunction on the pharmacokinetics of ribavirin after oral and intravenous dosing. Drug Discov. Ther. 8, 89–95 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Haegele, K.D. , Huebert, N.D. , Ebel, M. , Tell, G.P. & Schechter, P.J. Pharmacokinetics of vigabatrin: implications of creatinine clearance. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 44, 558–565 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stangier, J. , Rathgen, K. , Stähle, H. & Mazur, D. Influence of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral dabigatran etexilate: an open‐label, parallel‐group, single‐centre study. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 49, 259–268 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Murthy, B. & Schmitt‐Hoffmann, A. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ceftobiprole, an anti‐MRSA cephalosporin with broad‐spectrum activity. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 47, 21–33 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Türck, D. et al Pharmacokinetics of intravenous, single‐dose tiotropium in subjects with different degrees of renal impairment. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 44, 163–172 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Halstenson, C.E. , Triscari, J. , DeVault, A. , Shapiro, B. , Keane, W. & Pan, H. Single‐dose pharmacokinetics of pravastatin and metabolites in patients with renal impairment. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 32, 124–132 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dickinson, J. et al Effect of renal or hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of mirabegron. Clin. Drug Investig. 33, 11–23 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. He, G. , Massarella, J. & Ward, P. Clinical pharmacokinetics of the prodrug oseltamivir and its active metabolite Ro 64‐0802. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 37, 471–484 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nilsen, O.G. , Saltvedt, E. , Walstad, R.A. & Marstein, S. Single‐dose pharmacokinetics of lomefloxacin in patients with normal and impaired renal function. Am. J. Med. 92, 38S–40S (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Brody, S.R. , Humphreys, M.H. , Gambertoglio, J.G. , Schoenfeld, P. , Cundy, K.C. & Aweeka, F.T. Pharmacokinetics of cidofovir in renal insufficiency and in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis or high‐flux hemodialysis. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 65, 21–28 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bui, K. , She, F. & Sostek, M. The effects of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of naloxegol. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 54, 1375–1382 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lameire, N. , Malerczyk, V. , Drees, B. , Lehr, K. & Rosenkranz, B. Single‐dose pharmacokinetics of cefpirome in patients with renal impairment. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 52, 24–30 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gibson, T.P. , Granneman, G.R. , Kallal, J.E. & Sennello, L.T. Cefsulodin kinetics in renal impairment. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 31, 602–608 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Molander, L. , Hansson, A. , Lunell, E. , Alainentalo, L. , Hoffmann, M. & Larsson, R. Pharmacokinetics of nicotine in kidney failure. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 68, 250–260 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Randinitis, E.J. , Posvar, E.L. , Alvey, C.W. , Sedman, A.J. , Cook, J.A. & Bockbrader, H.N. Pharmacokinetics of pregabalin in subjects with various degrees of renal function. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 43, 277–283 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yamamoto, J. , Toublanc, N. , Kumagai, Y. & Stockis, A. Levetiracetam pharmacokinetics in Japanese subjects with renal impairment. Clin. Drug Investig. 34, 819–828 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Toon, S. , Ross, C.E. , Gokal, R. & Rowland, M. An assessment of the effects of impaired renal function and haemodialysis on the pharmacokinetics of fluconazole. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 29, 221–226 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cawello, W. , Fuhr, U. , Hering, U. , Maatouk, H. & Halabi, A. Impact of impaired renal function on the pharmacokinetics of the antiepileptic drug lacosamide. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 52, 897–906 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dettli, L. , Spring, P. & Habersang, R. Drug dosage in patients with impaired renal function. Postgrad. Med. J. Suppl:32–35 (1970). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dettli, L.C. Drug dosage in patients with renal disease. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 16, 274–280 (1974). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dettli, L.C. Elimination kinetics and drug dosage in renal insufficiency patients. Triangle 14, 117–123 (1975). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jelliffe, R.W. A mathematical analysis of digitalis kinetics in patients with normal and reduced renal function. Math. Biosci. 1, 305–325 (1967). [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bricker, N.S. , Morrin, P.A. & Kime, S.W. Jr. The pathologic physiology of chronic Bright's disease. An exposition of the “intact nephron hypothesis”. Am. J. Med. 28, 77–98 (1960). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brenner, B.M. & Rector, F.C. The Kidney. (Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 1976). [Google Scholar]

- 44. The Cleveland Clinic Foundation . Kidney Function Assessment by Creatinine‐Based Estimation Equations. http://www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/medicalpubs/diseasemanagement/nephrology/kidney-function/ (2010). Accessed 15 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Suchy‐Dicey, A.M. et al Tubular secretion in CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 2148–2155 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Masereeuw, R. et al The kidney and uremic toxin removal: glomerulus or tubule? Semin. Nephrol. 34, 191–208 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Duranton, F. et al Normal and pathologic concentrations of uremic toxins. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23, 1258–1270 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nauta, F.L. et al Glomerular and tubular damage markers are elevated in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care 34, 975–981 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vaidya, V.S. & Bonventre, J.V. Mechanistic biomarkers for cytotoxic acute kidney injury. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2, 697–713 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Vaidya, V.S. et al Urinary biomarkers for sensitive and specific detection of acute kidney injury in humans. Clin. Transl. Sci. 1, 200–208 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Drugs and solutes with a ratio greater than 0.74 and showing increase in ratio across the range of CKD (Group A).

Drugs and solutes with a ratio greater than 0.74 showing decrease in ratio across the range of CKD (Group B).

Drugs and solutes with a ratio greater than 0.74 showing decrease in ratio across the range of CKD (Group B).

Drugs and solutes with a ratio greater than 0.74 showing no statistically significant correlation (no change in ratio) across the range of CKD (Group C).

Drugs and solutes with a ratio greater than 0.74 showing no statistically significant correlation (no change in ratio) across the range of CKD (Group C).

Drugs and solutes with a ratio less than or equal to 0.74 showing no statistically significant correlation (no change in ratio) across the range of CKD.

Supplemental Information