Abstract

Over the last 25 years, the terminology of skin and soft tissue infections, as well as their classification for optimal management of patients, has changed. The so-called and recently introduced term ‘acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections’ (ABSSSIs), a cluster of fairly common types of infection, including abscesses, cellulitis, and wound infections, require an immediate effective antibacterial treatment as part of a timely and cautious management. The extreme level of resistance globally to many antibiotic drugs in the prevalent causative pathogens, the presence of risk factors of treatment failure, and the high epidemic of comorbidities (e.g. diabetes and obesity) make the appropriate selection of the antibiotic for physicians highly challenging. The selection of antibiotics is primarily empirical for ABSSSI patients which subsequently can be adjusted based on culture results, although rarely available in outpatient management. There is substantial evidence suggesting that inappropriate antibiotic treatment is given to approximately 20–25% of patients, potentially prolonging their hospital stay and increasing the risk of morbidity and mortality. The current review paper discusses the concerns related to the management of ABSSSI and the patient types who are most vulnerable to poor outcomes. It also highlights the key management time-points that treating physicians and surgeons must be aware of in order to achieve clinical success and to discharge patients from the hospital as early as possible.

Keywords: acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection, appropriate antibiotic therapy, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, poor outcome, severity, treatment failure

Introduction

For the last 25 years, complicated skin and skin structure infections (cSSSIs) and more recently acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSIs) have placed an increasing burden on healthcare systems globally.1 This burden is due to the initial increased spread and subsequent persistence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in some regions. Although diagnosis is based on clinical presentation, the bacterial etiology of cSSSIs and ABSSSIs is confirmed in over 60% of cases, and the evidence suggests the predominance of Gram-positive bacteria.1,2 Eradication of the causative pathogens requires effective antibiotic therapy against the most likely microorganism. Although recent clinical practice guidelines recommend a range of antibiotic therapies (with or without surgical interventions) for each type of skin infection, management may be challenging for physicians, and patients may suffer from a prolonged hospitalization when pathogens are drug-resistant or when host factors complicate the infection.3

This review paper has three aims: (1) to review the literature on SSSIs with a focus on the new category of ABSSSIs, assessing the evidence that these are clinically significant diagnoses often associated with a considerable morbidity; (2) to highlight that a relatively large proportion of ABSSSI patients receive inappropriate management; and (3) to emphasize the importance of appropriate management of ABSSSIs to minimize the risk of adverse outcomes.

Terminology changes: cSSSI vs ABSSSI

The term ‘skin and skin structure infections’ has historically encompassed a range of clinical syndromes, including both chronic (e.g. ischemic ulcer, diabetic foot infection [DFI]) and acute (e.g. complicated cellulitis and erysipelas, major cutaneous abscess, post-traumatic or post-surgical would infections, bite infections, burn wound infections) bacterial SSSIs.4–6 Uncomplicated SSSIs such as folliculitis or carbuncles are considered to be complicated if patients have underlying comorbidities that impact infection management6 and complicated SSSIs often require surgical source control in combination with empiric antibiotic therapy.4–6 Previous phase III studies aimed to investigate the antibacterial effects of antibiotics in these various clinical presentations, but due to the great variety of potential pathogens causing cSSSIs, the observed microbiological efficacy rates varied between indications. Patients with chronic cSSSIs are often colonized with bacteria that do not cause an acute infection requiring prompt empiric antibiotic therapy.4–7

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently introduced a new regulatory terminology – ‘acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections’ – which includes cellulitis, erysipelas, wound infection, and major cutaneous abscess, which excludes all other indications (Table 1).8,9 Based on the FDA guidance, an ABSSSI must have a minimum lesion size of 75 cm2 and present with the tetrad of erythema, tenderness, edema, and warmth as local signs of infection.8,10,11 The antibacterial effects of new antibiotics are being investigated at an early time-point (at 48–72 h) with the aim of assessing a clinical response, which may turn out to be a therapeutic decision point. It is assumed that an objective measurement of reduction in lesion size within 48–72 h would confirm the rapid action and effectiveness of antibiotics, although differences may exist between antibiotics with regard to the mechanism of eradication. It is also anticipated that a favorable early response would translate into late clinical cure after the end of therapy (EOT) and allow more rapid wound healing.12 These new FDA-defined primary endpoints were used in the clinical trials that led to the recent regulatory approval of the new Gram-positive agents oritavancin,13,14 dalbavancin,15,16 and tedizolid.17,18

Table 1.

| Prior guidance (1998)9 | New guidance (2013)8 | |

|---|---|---|

| Indication/terminology | Complicated skin and skin structure infection (cSSSI) | Acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection (ABSSSI) |

| Infection type | Varying sized abscesses, wound, cellulitis, DFI, chronic ulcer, burn infections | Large abscesses, wound, cellulitis, erysipelas of at least 75 cm2 surface area |

| Infection severity | Intermediate/severe | Intermediate/severe |

| Primary endpoints | Subjective Defined as: clinicians’ assessment at 7–14 days after EOT |

Objective Defined as: at least 20% reduction in lesion size at 48−72 h |

| Secondary endpoints | Varied Low potential for differentiation |

Primary endpoint sustained up to EOT Clinician’s assessment at EOT Higher potential for differentiation |

| Etiology | Chronic and acute infection Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria |

Acute infection Primarily Gram-positive bacteria; less frequently Gram-negative bacteria |

DFI, diabetic foot infection; EOT, end of therapy; FDA, US Food and Drug Administration.

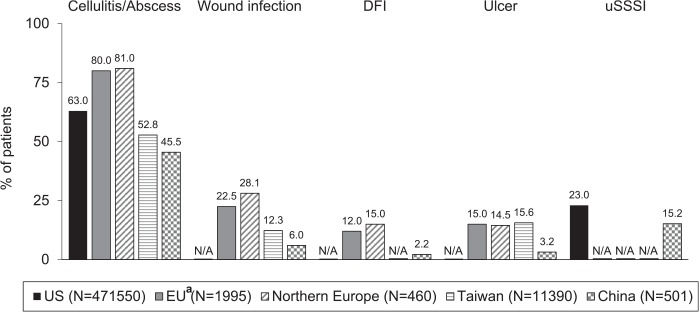

ABSSSIs consist of the most frequently diagnosed skin infections worldwide (Figure 1).2,19–22 According to a recent European retrospective study, of patients hospitalized with SSSIs, around 80% have cellulitis and/or abscess, and around 20% have wound infection (e.g. post-traumatic and post-surgical wound infections) and patients could present sometimes with more than one indication.2 Cellulitis and abscesses are diagnosed in around 50% of patients with cSSSIs in Taiwan21 and China,22 and a smaller proportion of patients are diagnosed with wound infections.21,22 In 1999, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) introduced a further classification of surgical site infections (SSIs) based on the depth of the infection.4,5,23 However, not all of these infection types in cSSSI would be classified as an ABSSSI according to the current criteria.

Figure 1.

Distribution of skin infection types in different regions.2,19–22

DFI, diabetic foot infection; N/A, not available; uSSSI, uncomplicated skin and skin structure infection.

aPatients could have had ⩾1 diagnosis; wound infections refer to post-surgical and post-traumatic infections.

Role of bacteria in ABSSSI

Cellulitis, erysipelas, and abscesses are primarily caused by Gram-positive bacteria, including S. aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and other beta-hemolytic streptococci.5,6,24–27 Coverage against Gram-positive bacteria therefore seems sensible as an initial empiric therapy for these conditions. The presence or absence of pus can be used to alert the clinician to the probability of an infection being staphylococcal (purulent) or streptococcal (non-purulent).6,7

In wound infections, however, the anatomical location of the wound is a critical component of the etiology. These infections may be caused by Gram-negative bacteria or anaerobes as well as Gram-positive bacteria.6,7,23,26 Gram-negative bacteria are the most likely causative agents in wound infections in the perianal or lower abdominal area,6,7 for example, while MRSA and methicillin-sensitive S. aureus (MSSA) are the predominant pathogens in wound infections following cardiothoracic surgery with possible severe complications such as endocarditis, bacteremia, or nosocomial pneumonia.28 For all ABSSSIs, the choice of empiric antibiotic therapy should be guided by both the likely pathogen involvement and local patterns of antimicrobial susceptibility.10

The complex etiology of more serious ABSSSIs

ABSSSIs may be either community-acquired or hospital-acquired, and the predisposing factors include trauma, chronic cutaneous lesions, pre-existing skin conditions (e.g. tinea pedis), edema due to venous insufficiency, and immunosuppression.29–31 The most serious ABSSSIs which require hospitalization for parenteral antibiotic therapy are identified based on (1) the nature of the potential causative pathogens (e.g. their virulence and resistance patterns) and (2) host factors pointing to the severity of the disease.10,31–34 If misdiagnosed or not managed appropriately, these acute infections can lead to complications that may have a devastating impact on quality of life and may increase the risk of mortality.

Drug-resistant bacteria such as MRSA causing ABSSSI are more challenging to treat due to the lack of availability of effective antibiotics on hospital formularies. The current high level of resistance globally in clinically relevant pathogens is a serious threat for both patients and physicians.35 MRSA emerged in the 1960s as a hospital-acquired pathogen due to the widespread use of penicillin and methicillin, and it has become endemic as a multidrug-resistant pathogen in hospitals worldwide.36 Evidence suggests that elderly patients who have had a prior exposure to a healthcare facility or hospital, or a prior antibiotic course or intravenous (IV) catheter remain at a higher risk of being colonized or infected with hospital-acquired MRSA.3 In the early 2000s, MRSA appeared in the community among younger people who had not been previously exposed to hospitals or healthcare institutions,21,36–38 who may instead have been colonized through sporting activities, crowding and IV drug abuse.3 These cases are termed community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA).36

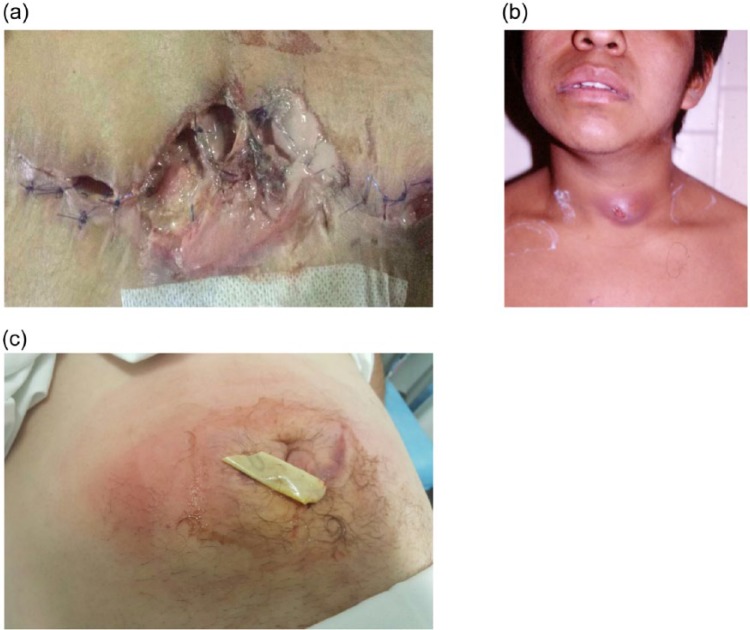

During diagnosis and severity assessment of an ABSSSI, certain host factors must be taken into consideration because they may alter management and require additional healthcare resource utilization. Cellulitis and erysipelas often occur in the lower extremities, with tinea pedis being considered as the entry point for pathogenic bacteria.12,26,39,40 The more serious ABSSSIs include rapidly spreading, extensive cellulitis, SSIs (see Figure 2), wound infections in the perianal area, and purulent infections in the neck, hand, face, and genitalia.39,41 Patients with ABSSSIs at these particular anatomical locations always require hospitalization for IV antibiotic treatment regardless of the baseline severity of the infection41 because surgical source control is difficult in these anatomical locations. In a recent French survey, infectious disease physicians noted that severe sepsis, poor social context, rapid progression of skin lesion, severe pain, and immunosuppression were among the most frequent causes of hospitalization of non-necrotizing cellulitis patients.39 After visiting the emergency department, observational units where patients can be monitored while receiving initial IV antibiotics for an ABSSSI can help to indicate whether hospitalization or outpatient management is most appropriate.42–44

Figure 2.

Representative images of ABSSSI indications: (a) Infected wound, (b) Abscess and (c) Cellulitis.

Images belong to the corresponding author.

ABSSSI, acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection.

Underlying comorbidities, especially in elderly patients, some of whom may have impairment in multiple organs, or diabetes, can complicate the management of ABSSSIs. Elderly patients often need renal or liver function monitoring or a central venous line, for example, during IV antibiotic treatment. Several studies have shown that diabetes is the most frequent (i.e. 8.7–40.7%) comorbidity among hospitalized ABSSSI patients.2,20,21,25,45 A recent European observational study in patients with cSSSIs linked several other conditions to the hospitalization, including peripheral vascular disease (21.2%), congestive heart disease (12.2%), renal disease (9.8%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or other respiratory conditions (9.5%), and malignancy (10.4%), which is associated with immunosuppressed status rendering patients more susceptible to infection.2,46 Several studies have investigated the factors associated with hospitalization or prolonged admission of patients with skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), a broad term which includes cSSSIs, ABSSSIs, and other infections. Among the identified factors were fever, age >65 years, comorbidity, previous treatment failure, hyponatremia, hypoalbuminemia, bacteremia, lactic acidosis, systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), previous ABSSSI history, and white blood cell count >15000/mm3 blood.42,43,47–51 These conditions must be investigated and monitored alongside any other comorbidities in order to assess the severity of ABSSSIs more accurately.

Regional distribution of pathogens in ABSSSIs, cSSSIs and cSSTIs

Analysis of the distribution of causative pathogens in ABSSSIs and cSSSIs reveals similarities across geographical regions, with S. aureus being the dominant pathogen, followed by streptococci and other Gram-positive bacteria (Table 2).2,20,24,26,52 However, in patients with infections coming under the broader category of cSSSIs, Gram-negative bacteria (e.g. Enterobacteriaceae, Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas spp) are also considered as causative pathogens, and these are very often found in mixed polymicrobial infections (e.g. DFI or wound infection) (Table 2).2,20,24,26,52

Table 2.

Regional distribution of pathogens in ABSSSIs, cSSSIs, and cSSTIs.

| US24 | US52 | REACH Study2 | Norway/Sweden20 | Spain26 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | SSTI (N = 422); abscess (81%), wound (11%), cellulitis (8%) | ABSSSI (N = 533); abscess (31.7%), cellulitis (60.0%), wound or purulent cellulitis (8.3%) | cSSSI (N = 1995) | cSSSI (N = 460) | cSSTI (N = 308); abscess (12.3%), cellulitis (70.8%), pressure ulcer (6.8%), other cSSTI (10.1%) |

| Data collection period | 2004 | 2010–2012 | 2010–2011 | 2008–2011 | 2010–2013 |

| Pathogens | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Anya | 384 (91.0)b | 202 (37.9) | 1001 (50.2)c | 432 (93.9)d | 95 (30.8)e,f |

| S. aureus | 320 (83.3) | 127 (62.8) | 383 (30.3) | 106 (24.5) | 33 (34.7) |

| MSSA | 71 (18.5) | 58 (28.7) | 279 (27.9) | 89 (20.6) | 22 (23.2) |

| MRSA | 249 (64.8) | 64 (31.6) | 102 (10.2) | 3 (0.7) | 11 (11.6) |

| CoNS | 12 (3.1) | 33 (16.3) | 112 (11.2) | 14 (3.2) | NR |

| VISA | NR | NR | 2 (<1) | NR | NR |

| Other staphylococci | NR | NR | NR | NR | 11 (11.6) |

| Streptococci | 30 (7.8) | 59 (29.2) | NR | 69 (16.0) | 13 (13.7) |

| S. agalactiae | 6 (1.5) | 32 (3.2) | 3 (0.7) | NR | |

| S. pyogenes | 2 (<1) | 37 (18.3)g | 40 (4.0) | 40 (9.3) | NR |

| Other beta-hemolytic | 3 (<1) | 66 (6.6) | 24 (5.6) | NR | |

| Anaerobic streptococci | 4 (<1) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Viridans group streptococci | 15 (3.9) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| S. anginosus group | NR | 15 (7.4) | NR | NR | NR |

| Other streptococci | NR | 2 (1.0) | NR | NR | NR |

| Enterococcus faecalis | NR | NR | 85 (8.5) | 2 (0.5) | NR |

| Enterococcus faecium | NR | NR | 29 (2.9) | 0 (0) | NR |

| Proteus mirabilis | 6 (1.5) | NR | NR | NR | 16 (16.8) |

| Gram-negative | NR | 20 (9.9) | 457 (45.7) | 22 (5.1) | 53 (55.8) |

| Anaerobic | NR | 17 (8.4) | NR | 4 (0.9) | 11 (11.6) |

ABSSSI, acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection; CoNS, coagulase-negative staphylococci; cSSSI, complicated skin and skin structure infection; cSSTI, complicated skin and soft tissue infection; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; N, number of patients studied; NR, not reported; SSTI, skin and soft tissue infections; VISA, vancomycin-intermediate Staphylococcus aureus.

Denominator for each of the subsequent categories.

Polymicrobial, 7.3%.

Polymicrobial, 30%.

Polymicrobial, 23.6%.

Polymicrobial, 30.5%.

144 cultures were tested.

Combined data for S. agalactiae, S. pyogenes and other beta-hemolytic streptococci.

First described in the United States,36,37 CA-MRSA has become endemic in Latin America53–55 and Asia,56 but it remains relatively infrequent in Europe.38 More recently, epidemiological data suggest that CA-MRSA has spread into hospitals in the United States and in Asia, rendering the implementation of effective infection control policies and antibiotic prescription more challenging.38,56

Table 3 shows the prevalence of MRSA in different regions of the world.25,57–63 Ongoing surveillance programs reveal that the prevalence of MRSA has been relatively low in Europe (17.4%)59 and Canada (19.8%),58 and relatively high in Latin America (58.3%),63 the United States (46.4%),57 and Asia (48.9–61.9%).60,62 However, all regions show variations between individual countries. For example, within Europe, Scandinavian countries report very low MRSA prevalence (e.g. <2–3%) while countries in Southern Europe report much higher prevalence (e.g. >50%).59 Similarly, within Asia, the prevalence of hospital-acquired MRSA ranges between 28% and over 70%.56

Table 3.

Prevalence of MRSA in various regions based on surveillance programs.

| Region | S. aureus (N) | MSSA (%) | MRSA (%) | Testing period | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | 43,331 | 53.6 | 46.4 | 2011–2014 | 57 |

| Canada | 2539 | 80.2 | 19.8 | 2010–2012 | 58 |

| Europe | 40,414 | 82.6 | 17.4 | 2013 | 59 |

| China | 6656 | 51.1 | 48.9 | 2004–2011 | 60 |

| Asia | 4117 | 47.5 | 52.5 | 2004–2006 | 61 |

| Asia Pacific | 1971 | 38.1 | 61.9 | 2012 | 62 |

| Latin America | 1066 | 41.7 | 58.3 | 2012 | 63 |

| Middle East/North Africa | NR | NR | 42.1 | Before 2014 | 25 |

MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; NR, not reported.

Unfavorable outcomes with inappropriate ABSSSI management

Given the complexity of ABSSSIs, it is perhaps not surprising that inappropriate management, resulting from misdiagnosis, under/overestimation of severity, failure to recognize risk factors, or use of the wrong type, or duration, of antibiotic, is not uncommon. The consequences of inadequate therapy include treatment failure and infection recurrence, both of which have implications for patient quality of life.12,64 Recurrence of the infection may occur in up to 75% of inappropriately managed SSTIs caused by CA-MRSA.41 Recurrence in erysipelas, a type of ABSSSI, may occur in 12–29% of patients with venous insufficiency being a major predisposing factor.65,66 In CA-MRSA endemic areas in the United States, SSTI patients often have recurrent SSTI episodes (in the past 12 months) in their medical history (i.e. 44%).67 Treatment failure associated with inappropriate management may be more likely to occur with complicated SSTIs (e.g. major abscess, cellulitis, wound infection, DFI, or ischemic ulcer) than with uncomplicated or mild SSTIs (e.g. impetigo, folliculitis, minor abscess, or carbuncles).41

The choice of initial antibiotic or treatment duration is a major factor in inappropriate treatment. Several independent reports indicate that a relatively large proportion of patients (range: 16.6–34.1%) receive inappropriate initial therapy leading to treatment failure, regardless of whether the infection was acquired in the community or in hospital. The definition of “inappropriate initial therapy” or “inappropriate management” differs between studies, but in most cases, the initial empiric antibiotic therapy is either delayed or inactive against the causative pathogen.41,64,68–70 Patients may also be considered treatment failures of the initial therapy when they require additional incision and drainage (i.e. 33.1%),68 debridement (i.e. 17.0%),68 amputation (i.e. 5.1%),68 change in antibiotic therapy or hospital admission,41,64,68,70 or if they develop a new lesion within 90 days.41 Inappropriate management, usually determined within 48–72 h, may increase the duration of hospital stay (additional 1.39–5.4 days),69,71 the risk of further hospital-acquired infections (e.g. nosocomial pneumonia),28 the risk of mortality (odds ratio [OR]: 2.91 [95% confidence interval: 2.34–3.62] according to Edelsberg et al.,71 and 1.2% versus 0.1%, p < 0.01 according to Berger et al.)64 and healthcare costs due to increased healthcare resource utilization.41,64,68–71 Even with monitoring in an observational unit for 24 h, up to 38% of ABSSSI patients may receive inappropriate treatment and require subsequent hospitalization.42

A retrospective analysis of patients hospitalized with uncomplicated SSTIs reported that considerable numbers of patients are treated for too long period of time and using an antibiotic with a too broad spectrum.72 With a definition of inappropriate treatment duration of 10 days or more, the mean total duration of antibiotic treatment was 12.6 days. Only 20.2% of patients received treatment within the appropriate duration and 28.2% received treatment for >14 days. What is more, a ⩾ 24 h of extended spectrum Gram-negative coverage, anaerobic cover, or unnecessary anti-pseudomonal coverage was received by 44.8%, 39.9%, and 17.2% of patients, respectively.

Among outpatients, lack of compliance with antibiotic treatment or underestimation of baseline infection severity contributes to the failure of initial therapy52,73,74 and in hospitalized patients, those with milder infections are frequently overtreated, while those with more severe infections might be undertreated.75 In a recent retrospective study in more severe infections, initial treatment failure occurred in 25% of the patients,26 similar to that previously reported for ABSSSI patients with mild or moderate infections.41,64,68,69

The type of hospital unit in which patients seek medical care also influences the likelihood of treatment success or failure: a recently published study highlighted that nearly twice as many cSSTI patients initially received inappropriate antibiotic therapy in rural hospitals than in urban hospitals (38.9% versus 21.3%, p = 0.02).68

Recognizing patient and disease risk factors is key to avoiding treatment failure. Among patients treated in emergency departments in the United States, initial treatment failure was associated with a variety of patient-level factors,76 including income, drug/alcohol abuse, obesity, drained infection, and age.76,77 In one of these studies, patients older than 65 years were nearly four-times more likely to fail initial therapy compared with younger patients (OR: 3.87), the chances of failure increasing by 43% with every 10-year increase in age.77 Infection duration and lesion size also influences the probability of treatment failure. In an observational study of 106 patients with S. aureus SSTIs, in which 21% failed treatment, independent predictors of failure were infection duration of 7 days or more (OR: 6.02) and a lesion diameter of 5 cm or more (OR: 5.25).78 In addition, the rate of inappropriate antibiotic selection was higher in patients failing treatment, compared with those not failing treatment, although the difference was not statistically significant (11% versus 4%, p = 0.20). In children, fever has been observed to double the risk of initial treatment failure.79

In the study by Berger et al., initial treatment failure (defined as a new antibiotic being given more than 24 h after hospital admission, drainage or debridement, or amputation more than 72 h after hospital admission) occurred in 16.6% of acute infections (cellulitis or abscess) and in 26.7% of SSIs.64 Treatment failure resulted in a longer hospital stay (an additional 4.1–7.3 days) and a higher probability of mortality.64 Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified bacteremia/SIRS, malnutrition, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, anemia, uremia, hyperglycemia, and required drainage/debridement in the first 48 h of hospital admission as significant risk factors for initial treatment failure in acute skin infections.64 Physicians should be particularly attentive to the management of patients who present with some of these less well-known risk factors.

The risk of treatment failure is increased in patients with both health complications and involvement of difficult-to-treat pathogens. In cSSTI patients, a combination of healthcare-associated risk factors and MRSA led to a greater likelihood of prolonged hospitalization and more frequent unscheduled visits to a healthcare provider, emergency department visits, or hospital admissions than either risk factor alone.69

In real-life settings, ABSSSIs may be very severe and the frequency of mortality and complications may be higher than in phase III clinical trials.13–15,17,18 In a retrospective Spanish study, patients were elderly (mean age: 71.3 years) and had nosocomial (9%), healthcare-associated (47%) or community-acquired infections (44%) predominantly affecting the lower extremities (71%).26 Cellulitis was the most frequent ABSSSI (71%), followed by abscess (12%), which was frequently associated with cellulitis or pyomyositis.26 This population was characterized by severe, complicated ABSSSIs: sepsis was present in 40% (CREST Class 4 severity) and bacteremia was present in 14% of the patients.26 In contrast, bacteremia was diagnosed in under 5% of ABSSSI patients in recent phase III trials.13–15,17,18 In the study by Macía-Rodríguez et al.,26 patients had multiple comorbidities, including heart failure, diabetes, and immunosuppression. In this study, the in-hospital mortality rate was 15% and the 6-month mortality rate was 8%.26 These rates may have been expected because complications of infection and comorbidities both increase the risk of mortality, but they are markedly higher than those reported in recent phase III clinical trials of randomized ABSSSI patients (0.2–0.6%).13–18 Further analysis of the risk factors in the Spanish study revealed that in-hospital mortality was independently associated with the presence of heart failure, chronic kidney disease, necrotic infection, and initial treatment failure.26 At 6 months, the risk of mortality was significantly increased by the presence of chronic kidney disease and immobility.26 Local epidemiological data revealed that MRSA prevalence was low and was not a dominant causative pathogen. MRSA was not, therefore, the major contributing factor to the high mortality rate among these patients.26

Together, these data suggest that both host factors and causative pathogens are critical to the outcome for hospitalized ABSSSI patients in real-life clinical settings, and their relative contributions should be given equal weight when making clinical management decisions.

ABSSSIs leading to complications prolonging antibiotic treatment or hospitalization

Hospitalization may be prolonged due to complications of a skin infection, including bacteremia (18.4%),45 osteomyelitis (7.2%),45 or necrotizing infections (1.1%).28,45 Among patients with bacteremia, SSTIs are the most frequent presumed source of infection,80 probably because S. aureus can cause invasive infections.81 Eradication of the persisting pathogen in bacteremia requires prolonged antibiotic treatment (14–21 days), and bactericidal antibiotics such as vancomycin or daptomycin are generally recommended for MRSA,82,83 although beta-lactams are more effective against MSSA.84 However, de novo resistance and the increasing prevalence of S. aureus strains with a vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) >1 µg/mL may occasionally lead to treatment failure or mortality.81,85–87 Osteomyelitis as a complication of SSTIs occurs more frequently in diabetic inpatients (13.3%) than in non-diabetics (5.2%).45 Osteomyelitis can manifest within days of an infection and requires several weeks, or even months, of antibiotic treatment. These types of complications occur four-times more frequently in diabetic than in non-diabetic patients,45 and physicians must consider many aspects of the antibiotic choice, including activity against the pathogen, penetration into bone in special populations, emerging adverse events, and de novo resistance potential.

Understanding the potential risk associated with a particular pathogen may guide physicians in selecting the most appropriate empiric therapy until culture and susceptibility results are known.3,88 MRSA remains a highly challenging pathogen in SSIs – hospital-acquired, purulent wound infections, some of which are classified as ABSSSIs. They normally occur up to 30 days post-operatively, following cardiothoracic, orthopedic, neurosurgery, general, vascular, or gynecological surgery, for example.89 Relative to uninfected surgical controls, patients with SSIs due to MRSA have an increased risk of hospital readmission within 90 days (OR: 35.0), increased risk of mortality within 90 days (OR: 7.27, p < 0.001) and may require up to a further 23 days in hospital (OR: 4.36).90

In cardiothoracic surgical patients, deep post-surgical sternal wound infection (secondary mediastinitis) is the most frequent infection. It is caused primarily by staphylococci91 and has a relatively high mortality rate. Due to the anatomical location, the most likely pathogens are skin colonizers such as coagulase-negative staphylococci or S. aureus. The presence of MRSA in such deep infections is independently associated with mortality compared with patients with MSSA.91 Mortality may also be related to other post-operative complications.28,83,91

Gram-negative bacteria, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumonia, or Escherichia coli, may be implicated in nosocomial wound infections in some patients.92,93 Recently approved agents with activity against these organisms, such as ceftazidime/avibactam or ceftolozane/tazobactam for the treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections (cIAI), used in combination with metronidazole, and of complicated urinary tract infections (cUTI), including pyelonephritis, may provide a future approach for suspected/confirmed Gram-negative ABSSSIs.

Prevention of SSIs in already-hospitalized patients is critical, particularly in regions where MRSA prevalence is high, due to the abovementioned complications.94 Previous studies have found that infections due to MRSA as opposed to MSSA are more complex in terms of management in hospital because of the additional steps that must be implemented (e.g. decolonization, protective clothing for nurses, isolation units, more expensive antibiotics, frequent laboratory tests, or blood cultures).69 Recent guidelines from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA) aim to improve clinical practice and reduce SSI rates in surgical units.95 A joint effort by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), the Surgical Infection Society (SIS), and the SHEA has led to the development of an improved guideline with regard to surgical antibiotic prophylaxis, which is consistent with antibiotic stewardship policies. The new guidelines recommend that a shorter antibiotic course is given within 60 min prior to surgical incision, using a weight-based dose to meet the therapeutic exposure even in obese patients.96 Selection of the particular antibiotic for prophylaxis may depend on local hospital epidemiology.96

Management of ABSSSI patients on the basis of new definitions, clinical practice guidelines and availability of new antibiotics

ABSSSI indications can present as mild, superficial infections or as life-threatening conditions affecting deeper tissue layer.7 In general, the management of all ABSSSI indications follows very similar algorithms and is based on the clinical presentation of the patient.7 Clinical practice guidelines separate purulent infections from non-purulent infections, and a third algorithm is outlined for wound infections.7 Although patients may be treated as outpatients, the initial diagnostic procedure may involve complex investigations (e.g. blood culture) and some imaging modalities which are more feasible in hospitals than in general practice.34 Physical examination and medical history-taking should include a thorough assessment of any predisposing factors such as trauma, underlying skin conditions, venous insufficiency, peripheral arterial disease, immunosuppression, malnutrition or previous surgery which can increase the likelihood and severity of skin infections.31

Obtaining accurate bacteriological and epidemiological information with susceptibility patterns via biospecimen collection is recommended.3,34 The quality of the sample taken from the lesion influences whether the isolated strain can be considered as a true pathogen or a colonizer. The findings from samples can be used to support the therapeutic decision if a patient did not improve during the initial empiric antibiotic therapy;12 thus, a careful collection of biospecimens is advised in order to guide antibiotic therapy.

In terms of sampling, pus can be easily collected with needle aspiration from wound infections and abscesses, but for cellulitis, and other non-purulent infections, a punch biopsy is recommended because swab samples and aspiration samples provide imprecise information.3,34 However, even punch biopsies generally have a low yield and so may be of limited value.34,97 A systematic review of clinical trials reported that only 16% of aspirations/punch biopsies were positive, with considerable variation in the rate ranges.98 While blood cultures offer an alternative for patients with signs of systemic toxicity or with significant co-morbidities, a US retrospective chart review of patients with complicated cellulitis revealed that only 2% of cultures returned useful information.99

While the importance to effective treatment of obtaining an accurate bacteriological profile using the most appropriate method according to guideline recommendations is not disputed,33,34 in daily practice, the choice of sampling methodology may be more pragmatic, driven not only by clinical presentation and the availability of material but also by the experience of the treating physician.34 Often, the choice of antibiotic may be based largely on patient risk factors, the antibiotics available on the formulary to the physician and local resistance patterns.33,34

The suspicion of Gram-positive bacteria as the cause of a community-acquired cellulitis, abscess or post-traumatic wound infection is reasonable, but other pathogens (especially drug-resistant pathogens) might also need to be considered when selecting antibiotic therapy depending on host factors and the individual patient’s medical history.7,100 For example, patients with peripheral arterial disease in the lower extremity may be infected with facultative anaerobic bacteria due to the local ischemic environment in soft tissues.34 When clinically indicated, blood samples are also taken to determine if the patients have bacteremia as skin infections often lead to this complication.26

The clinical practice guidelines published by the IDSA,7 the SIS4,5 and the World Society of Emergency Surgery101 are in agreement regarding the importance of surgical source control with the addition of empiric antibiotic therapy. Abscesses are initially managed with incision and drainage, which is then followed by antibiotic therapy in complicated and moderate or severe infections. Patients with wound infections benefit from surgical debridements to clean the infected areas deeper in the subcutaneous or muscle layers, accompanied by a regular change in wound dressing. Wound infections also require antibiotic therapy as described above. Cellulitis patients must be monitored for at least 24–48 h and surgical debridement applied only if the infection becomes necrotizing.4,5,101

Recently, several groups have reviewed the implementation of the new SSTI guidance in real-life clinical practice.12,31,33,34,102 Assessment of the severity of the ABSSSI is vital in the first instance, and failure to evaluate the severity correctly may lead to inappropriate treatment.12 The latest clinical practice guidelines define the levels of severity as mild, moderate or severe for both non-purulent and purulent infections.7 In general, severe infections are those in which patients suffer from hemodynamic instability or SIRS, and require immediate hemodynamic support and monitoring.34 The new guidance also requires that the antibiotic efficacy be evaluated 48–72 h after initiation of therapy,8 a time-point that coincides with the usual practice of evaluating the clinical response to empiric antibiotic therapy, with evaluation of culture results and information regarding potential resistance of the causative pathogen, which could trigger a change to the antibiotic therapy.12,70 The therapeutic value of this endpoint was highlighted by an analysis of the data from the real-life REACH study, which demonstrated that failure to achieve early response was associated with higher rates of initial treatment modification and poor outcome, and greater healthcare resource utilization, compared with achievement of early response.102 In routine clinical practice, physicians seldom measure the area of the lesion very accurately and it may therefore be unrealistic to expect that they would make clinical decisions about the continuation of antibiotic therapy based on any reduction in lesion size. However, an improvement in clinical symptoms (e.g. afebrile, less pain, lower degree of warmth, smaller erythema) may guide physicians’ decision-making about whether to maintain or change the empiric antibiotic therapy, or to step down to oral antibiotics.12 A lack of response should prompt physicians to change the antibiotic, guided by any available bacteriological information.64,70

Differences in prescribing behaviors are observed between physicians in every hospital.103 A recent study has shown that, in Europe, patients with cSSTIs receive IV antibiotics for at least ten days (up to 18 days in Poland) and may be hospitalized for up to 25 days (e.g. in Portugal).103 This large observational study highlighted that many patients who were eligible for an early switch from IV to oral antibiotic therapy or for early discharge from hospital in fact remained hospitalized and were exposed to the risk of more frequent adverse events, further hospital-acquired infections, or IV therapy-related complications.103 The principle of a switch to oral therapy and discharge from hospital as early as possible has been emphasized, both for the benefit of the patient and to reduce overall cost for healthcare systems. One randomized controlled trial (RCT) has demonstrated that a switch from IV vancomycin to oral linezolid shortened the overall duration of therapy for patients with SSTIs caused by MRSA.104

Selecting an antibiotic treatment for ABSSSI patients

The latest clinical practice guidelines recommend a range of antibiotics for purulent and non-purulent non-necrotizing infections as well as for wound infections, outlined in Table 4.7 Purulence indicates a staphylococcal infection for which incision and drainage can be key management components, unlike non-purulent infections which tend to be streptococcal and for which antibiotics are the mainstay of treatment. When risk of MRSA is low, patients can be treated with nafcillin, oxacillin, or clindamycin.7 For infections potentially caused by MRSA, an agent effective against this resistant pathogen should be given,3,7,100 and for patients requiring IV therapy, vancomycin is normally the first-line treatment. Although this antibiotic has been successfully used for many decades, current understanding dictates that therapeutic drug monitoring is necessary in patients with renal impairment and in obese patients in order to achieve efficient therapeutic exposure and to limit trough concentrations.105 Other recommended choices include teicoplanin, daptomycin, clindamycin, the beta-lactam ceftaroline, and tigecycline, the latter two of which are broad-spectrum antibiotics with activity against MRSA.7,12,33

Table 4.

Antimicrobial Therapy for Staphylococcal and Streptococcal Skin and Soft Tissue Infections.

| Disease Entity | Antibiotic | Dosage, Adults | Dosage, Childrena | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impetigob (Staphylococcus or Streptococcus) |

Dicloxacillin | 250 mg qid po | N/A | N/A |

| Cephalexin | 250 mg qid po | 25–50 mg/kg/d in 3–4 divided doses po | N/A | |

| Erythromycin | 250 mg qid poc | 40 mg/kg/d in 3–4 divided doses po | Some strains of Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes may be resistant | |

| Clindamycin | 300–400 mg qid po | 20 mg/kg/d in 3 divided doses po | N/A | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 875/125 mg bid po | 25 mg/kg/d of the amoxicillin component in 2 divided doses po | N/A | |

| Retapamulin ointment | Apply to lesions bid | Apply to lesions bid | For patients with limited number of lesions | |

| Mupirocin ointment | Apply to lesions bid | Apply to lesions bid | For patients with limited number of lesions | |

| MSSA SSTI | Nafcillin or oxacillin | 1–2 g every 4 h IV | 100–150 mg/kg/d in 4 divided doses | Parenteral drug of choice; inactive against MRSA |

| Cefazolin | 1 g every 8 h IV | 50 mg/kg/d in 3 divided doses | For penicillin-allergic patients except those with immediate hypersensitivity reactions. More convenient than nafcillin with less bone marrow suppression | |

| Clindamycin | 600 mg every 8 h IV or 300–450 mg qid po | 25–40 mg/kg/d in 3 divided doses IV or 25–30 mg/kg/d in 3 divided doses po | Bacteriostatic; potential of cross-resistance and emergence of resistance in erythromycin-resistant strains; inducible resistance in MRSA | |

| Dicloxacillin | 500 mg qid po | 25–50 mg/kg/d in 4 divided doses po | Oral agent of choice for methicillin-susceptible strains in adults. Not used much in pediatrics | |

| Cephalexin | 500 mg qid po | 25–50 mg/kg/d 4 divided doses po | For penicillin-allergic patients except those with immediate hypersensitivity reactions. The availability of a suspension and requirement for less frequent dosing | |

| Doxycycline, minocycline | 100 mg bid po | Not recommended for age <8 yd | Bacteriostatic; limited recent clinical experience | |

| Trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole |

1–2 double strength tablets bid po | 8–12 mg/kg (based on trimethoprim component) in either 4 divided doses IV or 2 divided doses po | Bactericidal; efficacy poorly documented | |

| MRSA SSTI | Vancomycin | 30 mg/kg/d in 2 divided doses IV | 40 mg/kg/d in 4 divided doses IV | For penicillin allergic patients; parenteral drug of choice for treatment of infections caused by MRSA |

| Linezolid | 600 mg every 12 h IV or 600 mg bid po | 10 mg/kg every 12 h IV or po for children <12 y | Bacteriostatic; limited clinical experience; no cross-resistance with other antibiotic classes; expensive | |

| Clindamycin | 600 mg every 8 h IV or 300–450 mg qid po | 25–40 mg/kg/d in 3 divided doses IV or 30–40 mg/kg/d in 3 divided doses po | Bacteriostatic; potential of cross-resistance and emergence of resistance in erythromycin-resistant strains; inducible resistance in MRSA. Important option for children | |

| Daptomycin | 4 mg/kg every 24 h IV | N/A | Bactericidal; possible myopathy | |

| Ceftaroline | 600 mg bid IV | N/A | Bactericidal | |

| Doxycycline, minocycline | 100 mg bid po | Not recommended for age <8 yd | Bacteriostatic; limited recent clinical experience | |

| Trimethoprim- sulfamethoxazole |

1–2 double strength tablets bid po | 8–12 mg/kg (based on trimethoprim component) in either 4 divided doses IV or 2 divided doses po | Bactericidal; limited published efficacy data | |

| Non-purulent SSTI (cellulitis) – streptococcal skin infections | Penicillin | 2–4 million units every 4–6 h IV | 60–100 000 units/kg/dose every 6 h | Antimicrobial agents for patients with severe penicillin hypersensitivity: |

| Clindamycin | 600–900 mg every 8 h IV | 10–13 mg/kg dose every 8 h IV | Clindamycin, vancomycin, linezolid, daptomycin, or telavancin. Clindamycin resistance is <1% but may be increasing in Asia | |

| Nafcillin | 1–2 g every 4–6 h IV | 50 mg/kg/dose every 6 h | N/A | |

| Cefazolin | 1 g every 8 h IV | 33 mg/kg/dose every 8 h IV | ||

| Penicillin VK | 250–500 mg every 6 h po | |||

| Cephalexin | 500 mg every 6 h po |

Abbreviations: bid: twice daily; IV: intravenous; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA: methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; N/A: not applicable; po: by mouth; qid: 4 times daily; SSTI: skin and soft tissue infection; tid: 3 times daily.

Doses listed are not appropriate for neonates. Refer to the report by the Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics [246], for neonatal doses.

Infection due to Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species. Duration of therapy is 7 days, depending on the clinical response.

Adult dosage of erythromycin ethylsuccinate is 400 mg 4 times/d po.

See [246] for alternatives in children.

Stevens DL, et al. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: 2014 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59 (2): e10-e52. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu296. Reproduced with permission of Oxford University Press on behalf of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. © The Author 2014 - All rights reserved. For permissions, please contact journals.permissions@oup.com

The recently approved agents, dalbavancin, oritavancin, and tedizolid, combine high potency against MRSA and other Gram-positive pathogens with desirable pharmacokinetic profiles. In pivotal phase III trials, both IV dalbavancin and IV oritavancin were shown to be non-inferior to vancomycin in terms of outcome.13–15 Safety profiles compared with vancomycin were favorable in the case of dalbavancin, with notably less nausea and pruritus,15 and similar with oritavancin.13,14 Dalbavancin and oritavancin offer the benefit of a long half-life and require only a single infusion on Day 1.12,16,33,106,107 Therefore, after treatment initiation and assessment of early clinical response, patients may be discharged from hospital when they are stable and afebrile for at least 48 h, although they must be monitored carefully for a longer period.108 An oxazolidinone such as linezolid or tedizolid, may offer an advantage when patients are expected to be switched to oral therapy after 1–2 days of IV infusion.7,12,109 Patients with limited venous access who can swallow tablets may benefit from the use of these drugs because their oral bioavailability is very high, their penetration into skin and soft tissue is sufficient and they do not need dose adjustment after switch.33 Compared with linezolid, tedizolid provides similar efficacy over a shorter course of therapy and with fewer doses per day. In two phase III trials, a 6-day course of once-daily 200 mg tedizolid was shown to be non-inferior to a 10-day course of twice-daily 600 mg linezolid in mainly S. aureus infections and to be associated with fewer gastrointestinal adverse events and lower risk of hematological events.17,18 Recent RCT evidence suggests that patients who are treated with tedizolid phosphate, oritavancin, or dalbavancin are likely to have a favorable prognosis in the long-term and to be clinically cured within weeks after the EOT.12

Clinical application

Optimizing the outcome of patients at a high risk of treatment failure relies on utilizing the most appropriate therapy which, in turn, demands accurate diagnosis and identification of patient risk factors. In daily clinical practice, this can be complex because, as outlined in this review, the characteristics of high-risk patients can be many and varied and include both disease- and host-associated factors. Clinical guidelines should always be consulted. Precise assessment of guideline-defined severity is crucial for effective treatment and clinicians should also be aware that infections with a large lesion size or a longer duration may be more likely to fail treatment. Close monitoring of patients with comorbidities, such as bacteremia, obesity, and low white blood cell count, and including some less well-recognized factors, such as uremia, is required, particularly in the elderly. Clinicians should also pay particular attention to patients with adverse host factors, such as drug/alcohol abuse and level of income. Given that inappropriate antibiotic selection is a common cause of treatment failure, accurate bacteriological information is key. However, in the empiric setting and/or where sampling is not possible, antibiotic choice can be based on the pathogens most likely to be involved in a particular infection (based on guidelines and the presence or absence of purulence) and local resistance patterns. Evaluation of antibiotic therapy at 48–72 h after initiation of treatment will enable non-responders to be identified early and an alternative approach to be considered.

Conclusion

ABSSSI management is not as straightforward as physicians may believe, and the rapid initiation of appropriate management may be critical to the overall outcome. Poor outcomes in ABSSSI patients are characterized by spreading infection, bacteremia, septic shock, osteomyelitis, recurrence, prolonged hospitalization, or death attributed to the ABSSSI. Particular populations including the elderly, and patients with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, immunosuppression, malignancy, or renal impairment require especially careful attention and management. A significant problem in clinical practice is the inappropriate selection of a suitable antibiotic based on patient presentation and the failure to distinguish between purulent and non-purulent infections in terms of pathogen involvement and antibiotic coverage. In addition, the role of culture data in clinical management is currently underrated, and approximately one in four patients receive antibiotic therapy that is inactive against the causative pathogen. ABSSSIs require immediate and in-depth attention because delayed or inappropriate therapy can lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support was provided by Highfield Communication, Oxford, United Kingdom, sponsored by Bayer, Germany.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest statement: Dr A Ortiz-Covarrubias has received honorarium fees as speaker from Bayer HealthCare, Sanofi, Abbott, MSD, and Silanes Labs. He has also received research funds from MSD, Astellas Pharma, and Glaxo Smith Kline. Dr A Jalife-Montaño has received honorarium fees as speaker from Farmasa. Professor A Pulido-Cejudo has received honorarium fees as speaker from Bayer HealthCare, Bard Davol, and Covidien. Dr M Guzmán-Gutierrez, Dr JL Martínez-Ordaz, Dr HF Noyola-Villalobos, and Dr LM Hurtado-López have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Abraham Pulido-Cejudo, Department of General Surgery, Hospital General de México, México City, México.

Mario Guzmán-Gutierrez, Department of General Surgery, Hospital General de México, México City, México.

Abel Jalife-Montaño, Department of General Surgery, Hospital General de México, México City, México.

Alejandro Ortiz-Covarrubias, Infectious Diseases Unit, Hospital Civil de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, México.

Jose Luis Martínez-Ordaz, Department of General Surgery, Centro Médico Nacional Siglo XXI, México City, México.

Héctor Faustino Noyola-Villalobos, Department of General Surgery, Hospital Central Militar, México City, México.

Luis Mauricio Hurtado-López, Department of General Surgery, Hospital General de México, México City, México.

References

- 1. Edelsberg J, Taneja C, Zervos M, et al. Trends in US hospital admissions for skin and soft tissue infections. Emerg Infect Dis 2009; 15: 1516–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Garau J, Ostermann H, Medina J, et al. Current management of patients hospitalized with complicated skin and soft tissue infections across Europe (2010–2011): assessment of clinical practice patterns and real-life effectiveness of antibiotics from the REACH study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2013; 19: E377–E385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bassetti M, Baguneid M, Bouza E, et al. European perspective and update on the management of complicated skin and soft tissue infections due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus after more than 10 years of experience with linezolid. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20(Suppl. 4): 3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. May AK. Skin and soft tissue infections. Surg Clin North Am 2009; 89: 403–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. May AK. Skin and soft tissue infections: the new surgical infection society guidelines. Surg Infect 2011; 12: 179–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dryden MS. Complicated skin and soft tissue infection. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65(Suppl. 3): iii35–iii44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59: e10–e52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections developing drugs for treatment, www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/./Guidances/ucm071185.pdf (2013, accessed 24 August 2016).

- 9. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: uncomplicated and complicated skin and skin structure infections: developing antimicrobial drugs for treatment, https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/98fr/2566dft.pdf (1998, accessed 24 August 2016).

- 10. Moran GJ, Abrahamian FM, Lovecchio F, et al. Acute bacterial skin infections: developments since the 2005 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines. J Emerg Med 2013; 44: e397–e412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Corey GR, Stryjewski ME. New rules for clinical trials of patients with acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections: do not let the perfect be the enemy of the good. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52(Suppl. 7): S469–S476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nathwani D, Dryden M, Garau J. Early clinical assessment of response to treatment of skin and soft-tissue infections: how can it help clinicians? Perspectives from Europe. Int J Antimicrob Ag 2016; 48: 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Corey GR, Kabler H, Mehra P, et al. Single-dose oritavancin in the treatment of acute bacterial skin infections. New Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2180–2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Corey GR, Good S, Jiang H, et al. Single-dose oritavancin versus 7–10 days of vancomycin in the treatment of gram-positive acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: the SOLO II noninferiority study. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60: 254–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, et al. Once-weekly dalbavancin versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection. New Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2169–2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dunne MW, Puttagunta S, Giordano P, et al. A randomized clinical trial of single-dose versus weekly dalbavancin for treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infection. Clin Infect Dis 2016; 62: 545–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Prokocimer P, De Anda C, Fang E, et al. Tedizolid phosphate vs linezolid for treatment of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: the ESTABLISH-1 randomized trial. JAMA 2013; 309: 559–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moran GJ, Fang E, Corey GR, et al. Tedizolid for 6 days vs linezolid for 10 days for acute bacterial skin and skin-structure infections (ESTABLISH-2): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14: 696–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ray GT, Suaya JA, Baxter R. Incidence, microbiology, and patient characteristics of skin and soft-tissue infections in a U.S. population: a retrospective population-based study. BMC Infect Dis 2013; 13: 252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jääskeläinen IH, Hagberg L, From J, et al. Treatment of complicated skin and skin structure infections in areas with low incidence of antibiotic resistance: a retrospective population based study from Finland and Sweden. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016; 22: 383.e1–383.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shen HN, Lu CL. Skin and soft tissue infections in hospitalized and critically ill patients: a nationwide population-based study. BMC Infect Dis 2010; 10: 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhao CJ, Liu YM, Zhao M, et al. Characterization of community acquired Staphylococcus aureus associated with skin and soft tissue infection in Beijing: high prevalence of PVL+ ST398. PLoS ONE 2012; 7: e38577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, et al. Guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1999; 20: 247–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ, et al. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. New Engl J Med 2006; 355: 666–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dryden M, Baguneid M, Eckmann C, et al. Pathophysiology and burden of infection in patients with diabetes mellitus and peripheral vascular disease: focus on skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015; 21(Suppl. 2): S27–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Macía-Rodríguez C, Alende-Castro V, Vazquez-Ledo L, et al. Skin and soft-tissue infections: factors associated with mortality and re-admissions. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2017; 35: 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kittang BR, Langeland N, Skrede S, et al. Two unusual cases of severe soft tissue infection caused by Streptococcus dysgalactiae subsp. equisimilis. J Clin Microbiol 2010; 48: 1484–1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tirilomis T. Daptomycin and its immunomodulatory effect: consequences for antibiotic treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus wound infections after heart surgery. Front Immunol 2014; 5: 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dupuy A, Benchikhi H, Roujeau JC, et al. Risk factors for erysipelas of the leg (cellulitis): case-control study. BMJ 1999; 318:1591–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wingfield C. Diagnosing and managing lower limb cellulitis. Nurs Times 2012; 108: 18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Falcone M, Concia E, Giusti M, et al. Acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections in internal medicine wards: old and new drugs. Intern Emerg Med 2016; 11: 637–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. CREST. Guidelines on the management of cellulitis in adults, http://www.acutemed.co.uk/docs/Cellulitis%20guidelines,%20CREST,%2005.pdf (2005, accessed 26 February 2017).

- 33. Pollack CV. Acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI): practice guidelines for management and care transitions in the emergency department and hospital. J Emerg Med 2015; 48: 508–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Amin AN, Cerceo EA, Deitelzweig SB, et al. Hospitalist perspective on the treatment of skin and soft tissue infections. Mayo Clin Proc 2014; 89: 1436–1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/index.html (2013, accessed 24 August 2016).

- 36. David MZ, Daum RS. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clin Microbiol Rev 2010; 23: 616–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baggett HC, Hennessy TW, Leman R, et al. An outbreak of community-onset methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin infections in southwestern Alaska. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2003; 24: 397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stefani S, Chung DR, Lindsay JA, et al. Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA): global epidemiology and harmonisation of typing methods. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2012; 39: 273–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lemaire X, Bonnet E, Castan B, et al. Management of non-necrotizing cellulitis in France. Med Mal Infect 2016; 46: 355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nathwani D. The management of skin and soft tissue infections: outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy in the United Kingdom. Chemotherapy 2001; 47(Suppl. 1): 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Labreche MJ, Lee GC, Attridge RT, et al. Treatment failure and costs in patients with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) skin and soft tissue infections: a South Texas Ambulatory Research Network (STARNet) study. J Am Board Fam Med 2013; 26: 508–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schrock JW, Laskey S, Cydulka RK. Predicting observation unit treatment failures in patients with skin and soft tissue infections. Int J Emerg Med 2008; 1: 85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Claeys KC, Lagnf AM, Patel TB, et al. Acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections treated with intravenous antibiotics in the emergency department or observational unit: experience at the Detroit Medical Center. Infect Dis Ther 2015; 4: 173–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Verastegui JE, Hamada Y, Nicolau DP. Transitions of care in the management of acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: a paradigm shift. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2016; 9: 1039–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Suaya J, Eisenberg DF, Fang C, et al. Skin and soft tissue infections and associated complications among commercially insured patients aged 0–64 years with and without diabetes in the U.S. PLoS ONE 2013; 8: e60057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shadyab AH, Crum-Cianflone NF. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections among HIV-infected persons in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: a review of the literature. HIV Med 2012; 13: 319–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Carratalà J, Rosón B, Fernández-Sabé N, et al. Factors associated with complications and mortality in adult patients hospitalized for infectious cellulitis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2003; 22: 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sabbaj A, Jensen B, Browning MA, et al. Soft tissue infections and emergency department disposition: predicting the need for inpatient admission. Acad Emerg Med 2009; 16: 1290–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Figtree M, Konecny P, Jennings Z, et al. Risk stratification and outcome of cellulitis admitted to hospital. J Infect 2010; 60: 431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Volz KA, Canham L, Kaplan E, et al. Identifying patients with cellulitis who are likely to require inpatient admission after a stay in an ED observation unit. Am J Emerg Med 2013; 31: 360–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Talan DA, Salhi BA, Moran GJ, et al. Factors associated with decision to hospitalize emergency department patients with skin and soft tissue infection. West J Emerg Med 2015; 16: 89–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jenkins TC, Knepper BC, McCollister BD, et al. Failure of outpatient antibiotics among patients hospitalized for acute bacterial skin infections: what is the clinical relevance? Am J Emerg Med 2016; 34: 957–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ribeiro A, Dias C, Silva-Carvalho MC, et al. First report of infection with community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in South America. J Clin Microbiol 2005; 43: 1985–1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ma XX, Galiana A, Pedreira W, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Uruguay. Emerg Infect Dis 2005; 11: 973–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Reyes J, Rincón S, Díaz L, et al. Dissemination of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 sequence type 8 lineage in Latin America. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49: 1861–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chen CJ, Huang YC. New epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus infection in Asia. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20: 605–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NHSN antibiotic resistance data, http://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/PSA/MapView.html (2015, accessed 24 August 2016).

- 58. Karlowsky JA, Adam HJ, Baxter MR, et al. In vitro activity of ceftaroline-avibactam against Gram-negative and Gram-positive pathogens isolated from patients in Canadian hospitals from 2010 to 2012: results from the CANWARD Surveillance Study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57: 5600–5611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe, http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/antimicrobial-resistance-europe-2014.pdf (2014, accessed 24 August 2016).

- 60. Lesher B, Gao X, Chen Y, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nosocomial pneumonia: role of linezolid in the People’s Republic of China. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2016; 8: 63–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Song JH, Hsueh PR, Chung DR, et al. Spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus between the community and the hospitals in Asian countries: an ANSORP study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011; 66: 1061–1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Biedenbach DJ, Alm RA, Lahiri SD, et al. In vitro activity of ceftaroline against Staphylococcus aureus isolated in 2012 from Asia-Pacific countries as part of the AWARE surveillance program. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 60: 343–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Biedenbach DJ, Hoban DJ, Reiszner E, et al. In vitro activity of ceftaroline against Staphylococcus aureus isolates collected in 2012 from Latin American countries as part of the AWARE surveillance program. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015; 59: 7873–7877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Berger A, Oster G, Edelsberg J, et al. Initial treatment failure in patients with complicated skin and skin structure infections. Surg Infect 2013; 14: 304–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jorup-Rönström C, Britton S. Recurrent erysipelas: predisposing factors and costs of prophylaxis. Infection 1987; 15: 105–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Eriksson B, Jorup-Rönström C, Karkkonen K, et al. Erysipelas: clinical and bacteriologic spectrum and serological aspects. Clin Infect Dis 1996; 23: 1091–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Forcade NA, Parchman ML, Jorgensen JH, et al. Prevalence, severity, and treatment of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) skin and soft tissue infections in 10 medical clinics in Texas: a South Texas Ambulatory Research Network (STARNet) study. J Am Board Fam Med 2011; 24: 543–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lipsky B, Napolitano LM, Moran GJ, et al. Inappropriate initial antibiotic treatment for complicated skin and soft tissue infections in hospitalized patients: incidence and associated factors. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2014; 79: 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lipsky B, Napolitano LM, Moran GJ, et al. Economic outcomes of inappropriate initial antibiotic treatment for complicated skin and soft tissue infections: a multicenter prospective observational study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2014; 79: 266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ruhe JJ, Smith N, Bradsher RW, et al. Community-onset methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft-tissue infections: impact of antimicrobial therapy on outcome. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44: 777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Edelsberg J, Berger A, Weber DJ, et al. Clinical and economic consequences of failure of initial antibiotic therapy for hospitalized patients with complicated skin and skin-structure infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2008; 29: 160–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Walsh TL, Chan L, Konopka CI, et al. Appropriateness of antibiotic management of uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections in hospitalized adult patients. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16: 721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Peterson D, McLeod S, Woolfrey K, et al. Predictors of failure of empiric outpatient antibiotic therapy in emergency department patients with uncomplicated cellulitis. Acad Emerg Med 2014; 21: 526–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Eells SJ, Nguyen M, Jung J, et al. Relationship between adherence to oral antibiotics and postdischarge clinical outcomes among patients hospitalized with Staphylococcus aureus skin infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60: 2941–2948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Marwick C, Broomhall J, McCowan C, et al. Severity assessment of skin and soft tissue infections: cohort study of management and outcomes for hospitalized patients. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011; 66: 387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. May L, Klein EY, Martinez EM, et al. Incidence and factors associated with emergency department visits for recurrent skin and soft tissue infections in patients in California, 2005–2011. Epidemiol Infect 2017; 145: 746–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Haran JP, Wilsterman E, Zeoli T, et al. Elderly patients are at increased risk for treatment failure in outpatient management of purulent skin infections. Am J Emerg Med 2017; 35: 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Lee GC, Hall RG, Boyd NK, et al. A prospective observational cohort study in primary care practices to identify factors associated with treatment failure in Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2016; 15: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Mistry RD, Hirsch AW, Woodford AL, et al. Failure of emergency department observation unit treatment for skin and soft tissue infections. J Emerg Med 2015; 49: 855–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Buitron de la Vega P, Tandon P, Qureshi W, et al. Simplified risk stratification criteria for identification of patients with MRSA bacteremia at low risk of infective endocarditis: implications for avoiding routine transesophageal echocardiography in MRSA bacteremia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2016; 35: 261–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hidayat LK, Hsu DI, Quist R, et al. High-dose vancomycin therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: efficacy and toxicity. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166: 2138–2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Barcia-Macay M, Lemaire S, Mingeot-Leclercq MP, et al. Evaluation of the extracellular and intracellular activities (human THP-1 macrophages) of telavancin versus vancomycin against methicillin-susceptible, methicillin-resistant, vancomycin-intermediate and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006; 58: 1177–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Chastre J, Blasi F, Masterton RG, et al. European perspective and update on the management of nosocomial pneumonia due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus after more than 10 years of experience with linezolid. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014; 20(Suppl. 4): 19–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Wong D, Wong T, Romney M, et al. Comparative effectiveness of β-lactam versus vancomycin empiric therapy in patients with methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) bacteremia. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2016; 15: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sakoulas G, Moise-Broder PA, Schentag J, et al. Relationship of MIC and bactericidal activity to efficacy of vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. J Clin Microbiol 2004; 42: 2398–2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hawser SP, Bouchillon SK, Hoban DJ, et al. Rising incidence of Staphylococcus aureus with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin and susceptibility to antibiotics: a global analysis 2004–2009. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2011; 37: 219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Van Hal SJ, Lodise TP, Paterson DL. The clinical significance of vancomycin minimum inhibitory concentration in Staphylococcus aureus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54: 755–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Shorr AF. Epidemiology and economic impact of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: review and analysis of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics 2007; 25: 751–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Engemann JJ, Carmeli Y, Cosgrove SE, et al. Adverse clinical and economic outcomes attributable to methicillin resistance among patients with Staphylococcus aureus surgical site infection. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 36: 592–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Anderson DJ, Kaye KS, Chen LF, et al. Clinical and financial outcomes due to methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus surgical site infection: a multi-center matched outcomes study. PLoS ONE 2009; 4: e8305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Mekontso-Dessap A, Kirsch M, Brun-Buisson C, et al. Poststernotomy mediastinitis due to Staphylococcus aureus: comparison of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible cases. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 32: 877–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Khan HA, Ahmad A, Mehboob R. Nosocomial infections and their control strategies. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2015; 5: 509–514. [Google Scholar]

- 93. Dubert M, Pourbaix A, Alkhoder S, et al. Sternal wound infection after cardiac surgery: management and outcome. PLoS ONE 2015; 10: e0139122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Barie PS, Itani KMF, Cheadle WG, et al. Preoperative preparation to avoid surgical site infections. Expert roundtable discussion. Surg Infect, http://www.sisna.org/scientific-studies (2013, accessed 9 January 2017).

- 95. Anderson DJ, Podgorny K, Berríos-Torres SI, et al. Strategies to prevent surgical site infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014; 35: 605–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Bratzler DW, Dellinger EP, Olsen KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2013; 70: 195–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Duvanel T, Auckenthaler R, Rohner P, et al. Quantitative cultures of biopsy specimens from cutaneous cellulitis. Arch Intern Med 1989; 149: 293–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Chira S, Miller LG. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common identified cause of cellulitis: a systematic review. Epidemiol Infect 2010; 138: 313–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Paolo WF, Poreda AR, Grant W, et al. Blood culture results do not affect treatment in complicated cellulitis. J Emerg Med 2013; 45: 163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, et al. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52: e18–e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Sartelli M, Malangoni MA, May AK, et al. World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) guidelines for management of skin and soft tissue infections. World J Emerg Surg 2014;9: 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Garau J, Blasi F, Medina J, et al. Early response to antibiotic treatment in European patients hospitalized with complicated skin and soft tissue infections: analysis of the REACH study. BMC Infect Dis 2015; 15: 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Nathwani D, Lawson W, Dryden M, et al. Implementing criteria-based early switch/early discharge programmes: a European perspective. Clin Microbiol Infect 2015; 21(Suppl. 2): S47–S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Itani KM, Weigelt J, Li JZ, et al. Linezolid reduces length of stay and duration of intravenous treatment compared with vancomycin for complicated skin and soft tissue infections due to suspected or proven methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Int J Antimicrob Agents 2005; 26: 442–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]