Abstract

Quality of life is an important measure of outcome in intensive care survivors. As return to employment is a key determinant of quality of life, we performed a prospective observational, cohort study of 75 intensive care unit patients who survived to hospital discharge. Approximately 2 years after intensive care unit discharge, 64% (18/28) of those employed before intensive care unit had returned to work. Of the rest, 10 were not working, two were unemployed, one was temporarily sick and seven were permanently sick. When health utility scores were assessed in the various employment categories, quality of life was particularly poor in the unemployed and permanently sick with median (interquartile range) scores of 0.082(−0.045−0.665) and 0.053(−0.160−0.769) respectively. Of the retired population, 95% returned to their own home with 50% requiring a family member to act as their carer. This study has demonstrated that patients who returned to work after a critical illness had a better quality of life at follow up, compared to the unemployed and permanently sick. In addition, there may be a burden on family members who act as carers for their relatives on discharge from hospital after a critical illness. Further work is required in this important area.

Keywords: Return to work, occupational status, critical care, quality of life, rehabilitation

Introduction

Within the critical care environment there is a growing recognition that an individual’s subsequent quality of life is an important consideration when contemplating the commencement of investigations, interventions and organ support. In critical care, these interventions are highly invasive and are, in some cases, prolonged. Not unreasonably, patients and their proxies often want to know what their lives will be like on subsequent hospital discharge. Whilst it is possible to make general predictions based on the outcomes of large groups, it is much more difficult to provide accurate predictions for individual patients.

There is a growing body of evidence, primarily from observational studies, demonstrating significant functional deterioration after a critical illness.1–11 This can take months or years to resolve and some patients never reach their previous functional status.4 The studies have been disparate in terms of study populations and country of study; however, psychological and functional disabilities appear to be consistent amongst intensive care unit (ICU) survivors.4,5,9–11

The aim of intensive care is to support patients through their critical illness and return them to their premorbid state. This ‘state’ not only includes their physical health but also their psychological well-being and financial independence. The ability to work is an important end point in the recovery process; it is associated with better physical and mental health and, as a consequence, improved quality of life.12 A recent UK study explored the socioeconomic impact of surviving a critical illness on patients and their families.3 Two hundred and ninety three patients completed the 1 year follow up. It was found that 28% of survivors and their families had a significant reduction in their income at 1 year after ICU discharge, and compared with baseline demographics, an additional 50% of patients were reliant on means other than employment alone for their income.3 In 2010, a Norwegian group prospectively followed 194 patients for 1 year.13 Prior to admission, they found that 63% of patients were students or working and by 1 year, 55% had returned to work or school. They also found that return to work was associated with a significantly higher quality of life when this was measured using Short Form 36.

The aim of this study was to determine the vocational outcomes of working age patients in terms of ability to return to work, and in the retired population their ability to return to their own home and live independently. We also aimed to show how quality of life differed amongst patients when categorised by their ‘work’ status. This has not been addressed in previous studies.

Methods

All patients admitted to the Glasgow Royal Infirmary ICU between 1 August 2008 and 31 July 2009 were eligible for inclusion and were identified from the electronic audit system ‘Wardwatcher’ (Critical Care Audit Ltd, Otley, UK). This database is used in every Scottish ICU to audit performance and outcomes between the units. It is jointly run by the Scottish Intensive Care Society and the Information Services Division of NHS Scotland.

A locally designed questionnaire was used to explore aspects of employment before and after intensive care discharge. In addition, the validated EQ 5D quality of life tool (© 1990 EuroQuality of Life Group) was utilised. This tool comprised two parts: a simple five question descriptive component which explored the various health domains and a visual analogue scale about the quality of life on the day the questionnaire was completed. Each of the five questions had three possible responses which were numbered from 1 to 3. The resultant five-digit sequence was then used to determine a health utility score, derived from a time trade-off method. In the EQ 5D evaluations, a health utility score of 1 equates to the best health state possible, 0 with death and negative utility scores equate to a state worse than death. As different nations have different cultures and beliefs, health utility scores are country specific. The relevant UK utility scores were derived from 3000 subjects, randomly sampled from the national postcode address file.14

Initially the GP practice of the potential participant was contacted. This was undertaken primarily to ensure that the patient had not died since hospital discharge therefore avoiding unnecessary distress to relatives. In addition, the appropriateness of contacting patients to answer questionnaires pertinent to their critical illness was queried. If patients had changed primary care physician, the new contact details were sought from the GP registrations unit. If no further details were available, the patients were not contacted.

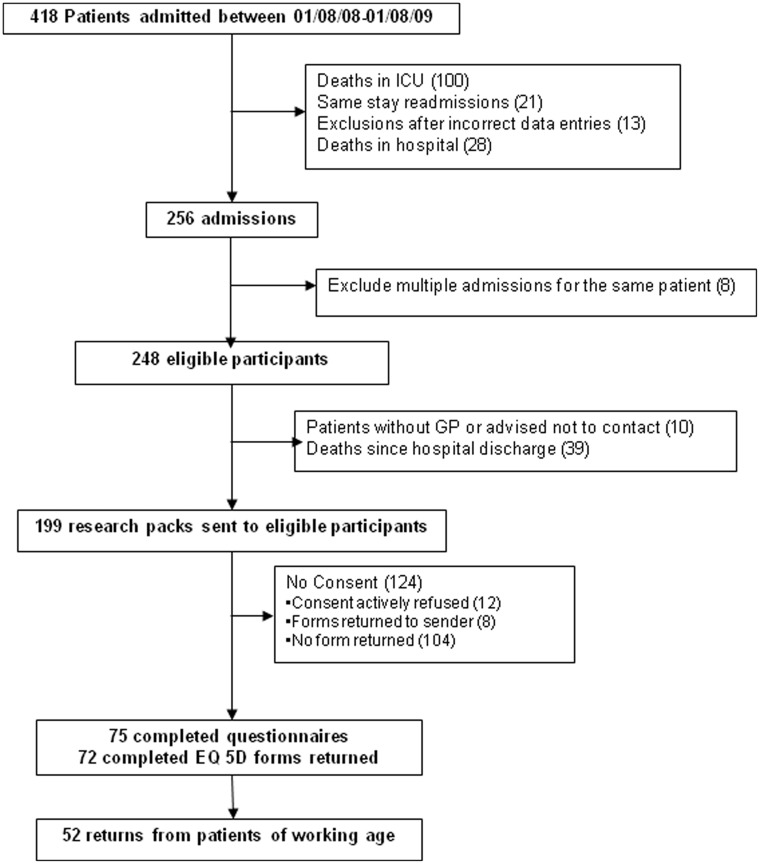

After excluding patients who died, 248 patients were eligible to be included in the study. After excluding those with no GP, those patients that the GP advised us not to contact for any reason, or those who had died during the follow-up period, 199 patients were eligible to participate in the study (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram showing patient flow through the study.

After collecting information regarding their ICU stay from Wardwatcher, a pack containing a letter of invitation, a consent form, a patient information sheet, the locally designed questionnaire and the EQ 5D quality of life tool was posted to eligible participants. If preferred, patients were offered a face to face or telephone interview. If no reply was received after a month, a reminder letter was sent out. If there was still no reply, it was assumed that the patient was not willing to participate in the study.

Data were analysed using SPSS version 18 (IBM Corporation, New York, USA). Having checked normality of the data, where appropriate, non-parametric tests such as the Chi square test, Fisher’s exact test, Spearman’s rank correlation, Mann Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis tests were used. Non-parametric data was presented as a median and interquartile range (IQR). When the data were normally distributed, the Pearson correlation and independent samples T test were used.

Ethics and R&D management approval was granted for the conduct of the study (WoS Rec 3 Committee, reference number 10/S0701/62).

Results

Of the 199 questionnaires sent out to former patients, eight were returned as the patients were no longer registered at the address held on record, 12 patients declined to be involved and a further 104 failed to return forms. In total, 75 patients returned the questionnaires although three patients did not complete the EQ 5D form (Figure 1). Of those who responded, 52 were of working age (aged 16–64 years) and 23 had retired (65 years and over). The median time of follow up, determined from the time between hospital discharge and the date that the questionnaires were posted, was 817 days (IQR 728–892).

Prior to admission to ICU, of the 52 working age patients, 53.8% were employed, 11.5% were unemployed, 1.9% were carers and 5.8% were full time students, 17.3% were either temporarily or permanently sick and 9.6% were in early retirement. We did not ascertain whether the early retirement was for health reasons (Table 1).

Table 1.

Work status before and after ICU for the working age population.

| Working age population (n = 52) (%) | Work status prior to ICU | Work status since ICU |

|---|---|---|

| Employed | 28 (53.8) | 18 (34.6) |

| Unemployed | 6 (11.5) | 9 (17.3) |

| Full time student | 3 (5.8) | 2 (3.8) |

| Intending to work but temporarily sick | 1 (1.9) | 2 (3.8) |

| Permanently long term sick | 8 (15.4) | 15 (28.8) |

| Retired from paid work | 5 (9.6) | 6 (11.5) |

| Looking after home/family | 1 (1.9) | 0 |

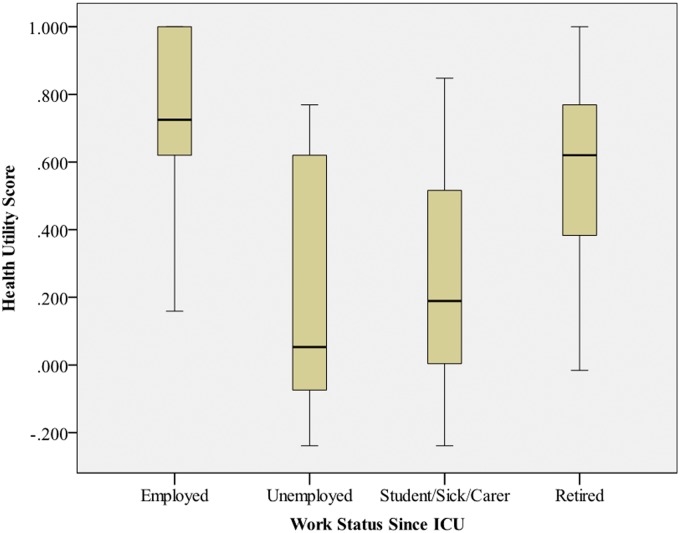

After ICU, 64% (18/28) of those working before ICU were able to return to work. The patients employed prior to ICU were categorised into those who did or did not get back to work (Table 2). There did not appear to be any statistically significant difference in the demographics of the two groups whilst they were in the ICU; however, the health utility scores were significantly higher in those who were able to return to work compared to those who could not (p < 0.001). In those returning to work, 14 were able to resume their original position; one respondent was promoted whilst three others had to take on a different role because of continuing health issues. Those patients who did not return to work were more likely to become permanently or temporarily sick (n = 6) than to become unemployed (n = 3). The relationship between quality of life and different work categories was explored using the health utility scores derived from the EQ 5D. We found that the employed reported the best quality of life and this was highly statistically significant (p < 0.001) (Table 3, Figure 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the patients employed prior to ICU when categorised into those who did or did not get back to work after ICU.

| n (%) or median (IQR) | Employed (n = 18) | Workless (n = 10) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 46 (41–52) | 45 (40–51) | 0.67 |

| APACHE II | 10.5 (8–16.23) | 13 (3–19.3) | 0.65 |

| Predicted hospital mortality (%) | 6.5 (4–22.5) | 14.9 (4.3–37.7) | 0.34 |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 2.5 (1–4.25) | 3 (1–43) | 0.63 |

| Hospital length of stay (days) | 15 (6.75–35.3) | 41 (32–98) | 0.072 |

| EQ 5D | |||

| At least some problems with mobility | 7 (38.9) | 10 (100) | 0.003 |

| At least some problems with self-care | 0 | 10 (100) | <0.001 |

| At least some problems with usual activities | 7 (38.9) | 9 (90) | 0.001 |

| At least moderate pain | 9 (50) | 9 (90) | 0.025 |

| At least moderate depression/anxiety | 9 (50) | 9 (90) | 0.019 |

| Health utility | 0.73 (0.6–1.0) | 0.14 (−0.02–0.52) | <0.001 |

Table 3.

Characteristics of the ICU patients determined by their work status after ICU.

| Median (IQR) | Employed (n = 18) | Unemployed (n = 10) | Sick/Student/Carer (n = 20) | Retired (n = 27) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 46 (41–52) | 46 (39–51) | 47 (39–57) | 70 (66–74) | <0.001 |

| APACHE II | 11 (8–17) | 15 (11–21) | 14 (8–22) | 17 (13–24) | 0. 017 |

| Predicted mortality (%) | 6.5 (4–22.5) | 14.9 (5.3–20.4) | 19.8 (3.8–31.9) | 27 (14.8–63.7) | 0.049 |

| ICU LOS (days) | 2.5 (1–4.25) | 1.5 (1–19.8) | 3.5 (1–12.8) | 3 (1–9) | 0.969 |

| Hospital LOS (days) | 15 (6.8–35.3) | 46.5 (14.3–93.3) | 27.5 (8.3–49) | 31 (16–59) | 0.127 |

| Health utility | 0.77 (0.62–1) | 0.05 (−0.10–0.64) | 0.19 (−0.02–0.52) | 0.62 (0.28–0.77) | <0.001 |

LOS: length of stay.

Figure 2.

Boxplot demonstrating the health utility scores in different work categories.

With regard to the retired population, 22 out of 23 patients were able to return to their own home although 50% of them now had to have a family member acting as a carer. From their EQ 5D evaluations, 52% had problems with mobility, 30% problems with self-care, just over 55% had some problems or were unable to perform their usual activities, 78% were suffering from moderate or extreme pain and just under 50% felt moderately anxious or depressed.

Discussion

The aim of this observational study was to investigate how surviving a critical illness altered employment status and social dependency. Just over 50% of the working age respondents were employed prior to intensive care and this reduced to around 35% over 2 years after discharge. Moreover, approximately 30% of respondents were deemed temporarily or permanently sick at follow up. It was concerning that after such a prolonged hospital discharge, intensive care survivors in this study were not able to work or seek work but had residual disabilities causing them to become a young, chronically sick group. As our patient population is from a highly deprived area, traditionally more of the available work involves manual labour. Residual physical deficits may therefore limit employment opportunities, making this group financially vulnerable. In addition, there may be continued deterioration in their physical and mental health. Indeed, even in those who did return to work, about 15% had to take on a different position because of continuing health issues. Whether further intervention could improve their health and allow them to re-engage in finding work was not explored in this study.

There were no differences in the demographics of the employed patients who did and did not return to work after ICU. Despite the severity of illness scores and hospital length of stay being similar in the two groups, there were marked differences in the quality of life domains at follow up. This suggests that it may not just be the critical illness, but other factors that potentially contributed to the residual health problems.

The population over the age of 65 had been independent prior to ICU admission for their critical illness and whilst it was gratifying that the vast majority were able to return to their own home, 50% now had a family member acting as a carer. This study did not ascertain the nature of the care required but clearly this should be explored further. Moreover, this study did not examine how this affected the employment and finances of the carer which is an important area requiring further research.

This study is limited by the nature of it being from a single centre and observational in its design. Whilst the response rate was only 37.5%, this is in keeping with that found in other ICU patient surveys from the UK.1,2 It is prone to bias as patients who returned to their premorbid state may be less inclined to complete a questionnaire related to quality of life and return to work; however, the findings are not that dissimilar from that found in recent studies.3

This is the third UK study addressing return to work after a critical illness and the first that has assessed quality of life amongst different employment groups. Work status is an important social determinant of health and health inequalities; unemployment is associated with poorer health outcomes whilst re-employment can lead to improvements in health.12 As with many other studies in the field of work and health15,16 it is unclear in this study whether unemployment causes deteriorating health or whether those with poor health are more likely to become unemployed. It was interesting to note that previously employed patients who were unable to return to work had significantly worse quality of life. Despite the small number of participants, this study has signalled a possible association between work status and quality of life in the critically ill which should be examined further. A prospective study assessing patients at regular intervals and over a longer time period would be useful to better understand how employment status alters after ICU discharge.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Cuthbertson BH, Scott J, Strachan M, et al. Quality of life before and after intensive care. Anaesthesia 2005; 60: 332–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuthbertson BH, Roughton S, Jenkinson D, et al. Quality of life in the five years after intensive care: a cohort study. Crit Care 2010; 14: R6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffiths J, Hatch RA, Bishop J, et al. An exploration of social and economic outcome and associated health related quality of life after critical illness in general illness in general intensive care unit survivors: a 12 month follow up study. Crit Care 2013; 17: R100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matte A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2011; 364: 1293–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hopkins RO, Jackson JC. Long-term neurocognitive function after critical illness. Chest 2006; 130: 869–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Needham DM. Mobilizing patients in the intensive care unit – improving neuromuscular weakness and physical function. JAMA 2008; 300: 1685–1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orme J, Jr, Romney JS, Hopkins RO, et al. Pulmonary function and health-related quality of life in survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Resp Crit Care 2003; 167: 690–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poulsen JB, Moller K, Kehlet H, et al. Long-term physical outcome in patients with septic shock. Acta Anaesthiol Scand 2009; 53: 724–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rimachi R, Vincent JL, Brimioulle S. Survival and quality of life after prolonged intensive care unit stay. Anaesth Intensive Care 2007; 35: 62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skinner EH, Warrillow S, Denehy L. Health-related quality of life in Australian survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med 2011; 39: 1895–1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Schaaf M, Beelen A, Dongelmans DA, et al. Poor functional recovery after a critical illness: a longitudinal study. J Rehabil Med 2009; 41: 1041–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waddell G and Burton AK. Is work good for your health and well-bring? 2006, pp.1–257. http://www.dwp.gov.uk/docs/hwwb-is-work-good-for-you.pdf (accessed 4 April 2014).

- 13.Myhren H, Ekeberg O, Stokland O. Health-related quality of life and return to work after critical illness in general intensive care unit patients: a 1-year follow-up study. Crit Care Med 2010; 38: 1554–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szende A, Oppe M, Devlin N. EQ-5D value sets: inventory, comparative review and user guide, The Netherlands: Springer, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Flint E, Bartley M, Shelton N, et al. Do labour market status transitions predict changes in psychological well-being? J Epidemiol Community Health 2013; 67: 796–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popham F, Gray L, Bambra C. Employment status and the prevalence of poor self-rated health. Findings from UK individual-level repeated cross-sectional data from 1978 to 2004. BMJ Open 2012; 2: e001342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]