Abstract

The present study was carried out to observe the impact of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) on collagen I derived from vaginal fibroblasts in the context of pelvic organ prolapse (POP), and explore the downstream effects on MAPK and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling. After treating primary cultured human vaginal fibroblasts (HVFs) derived from POP and non-POP cases with AGEs, cell counting was carried out by sulforhodamine B. The expression levels of collagen I, receptor of advanced glycation end products (RAGE), matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) were detected by western blot analysis and PCR. RAGE, MAPK and NF-κB were molecularly and pharmacologically-inhibited by siRNA, SB203580 and PDTC, respectively, and downstream changes were detected by western blot analysis and PCR. Inhibition of HVF proliferation by AGEs occurred more readily in POP patients than that noted in the controls. After treatment with AGEs, collagen I levels decreased and MMP-1 levels increased to a greater extent in the HVFs of POP than that noted in the controls. During this same period, RAGE and TIMP-1 levels remained stable. Following treatment with AGEs and RAGE pathway inhibitors by siRNA, SB203580 and PDTC, the impact induced by AGEs was diminished. The inhibition of p-p38 MAPK alone was not able to block the promoting effect of AGEs on the levels of NF-κB, which suggests that AGEs may function through other pathways, as well as p-p38 MAPK. On the whole, this study demonstrated that AGEs inhibited HVF proliferation in POP cases and decreased the expression of collagen I through RAGE and/or p-p38 MAPK and NF-κB-p-p65 pathways. Our results provide important insights into the collagen I metabolism in HVFs in POP.

Keywords: pelvic organ prolapse, advanced glycation end products, receptor of advanced glycation end products, collagen I, MAPK, nuclear factor-κB

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is a major health concern for women in the reproductive and menopausal years. POP involves the decent of pelvic organ and the pelvic floor, caused by insufficiency of the fibrous connective tissue and striated muscles that form the pelvic floor (1). Fibroblasts and their product collagen are the main components within the connective tissue. The change in the number of fibroblasts in pelvic floor connective tissue may cause changes in the collagen content (2,3), and the functionality of fibroblasts may also be related to a deficiency of collagen, which has been observed in patients with POP (4). The type, amount and degree of cross-linking of collagen contribute to the tension of the connective tissue. Collagen I specifically contributes to the tensile force of the connective tissue forming the pelvic floor, and is degraded by a family of enzymes called the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), whose expression levels are modulated by locally produced tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) (5). General speaking, changes in both the qualitative and quantitative properties of collagen have been linked to patients with POP (6,7). In 1996, Jackson et al (7) demonstrated that genitourinary prolapse is associated with a reduction in total collagen content supporting the findings of another study (8). Kerkhof et al found that pyridinoline collagen cross-links which reflect the level of mature collagen in the prolapse site increased significantly, compared to the non-prolapse group (9). Vulic et al found there was increased expression of MMP-1 and decreased expression of collagen I in uterosacral ligaments of women with POP compared with non-POP women (10). Dviri et al concluded that the expression of MMP-1 and MMP-9 appears to be increased in tissues from women with POP (11). Wang et al demonstrated that TIMP-1 expression levels in a POP patient group were significantly lower than those in the control group (12). Thus, it is hypothesized that changes in the metabolism of collagen I are regulated by MMP-1 and TIMP-1, and other matrix metalloproteinases and its tissue inhibitors, are related to the physiopathology of POP.

Moreover, it has been confirmed that the metabolism of collagen can be impacted by advanced glycation end products (AGEs) (13). AGEs, the products of nonenzymatic glycation and oxidation of proteins and lipids, accumulate in diverse biological settings including: diabetes, inflammation, renal failure and aging. AGEs adjust the metabolism of target proteins through the receptor of advanced glycation end products (RAGE) (14), and activate an array of signal transduction cascades, such as MAPK, ROS, p38, NO and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). Together these pathways are involved in numerous biological functions including, but not limited to: skin aging, cardiovascular injury and remodeling, diabetes, inflammation and gingival hyperplasia (15,16). In the context of skin aging, AGEs promote fibroblast apoptosis, inhibit the synthesis of collagen, and accelerate the degradation of collagen through the balance of MMP and TIMP (17), which may be similar to the metabolic change in collagen in connective tissue of the pelvic floor in POP.

Concerning the actual role of AGEs in the pathological physiology of POP, Jackson et al also found that both intermediate intermolecular cross-links and advanced glycation cross-links were increased in prolapsed tissue (7). Moreover, our previous study indicated that collagen I levels were decreased in prolapse tissue while the expression of AGEs in prolapse tissue was concomitantly increased. RAGE expression, however, was found to remain stable in pelvic tissue of prolapsed patients (18). Thus, we speculated that AGEs impact the metabolism of collagen in the pelvis through RAGE on the surface of fibroblasts and downstream pathways; however, the related mechanism remains to be elucidated, and there is no information concerning the role of AGEs and its receptor in POP. In the present study, we describe the metabolism of collagen I activated by AGEs through MMP-1, TIMP, and changes in p38 and NF-κB following AGE-RAGE interactions.

Materials and methods

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University, Shanghai, China. This study included two parts: i) the impact of AGEs on the metabolism of collagen I in human vaginal fibroblasts (HVFs) obtained from patients with POP. Six primary cultured HVF samples from 3 cases of POP (51, 71 and 65 years of age, respectively), and 3 cases of non-POP (55, 57 and 70 years of age, respectively), were collected. The protein expression of collagen I, MMP-1, TIMP-1 and RAGE were chosen for study; ii) the mechanism involved in the impact of AGEs on the metabolism of collagen I in primary cultured HVFs; the molecules, RAGE, p38 MAPK and NF-κB were selected for study.

Reagents

Anti-collagen I (sc-136154), anti-AGE (ab23722) antibody, anti-RAGE monoclonal antibody (sc-365154) and anti-vimentin monoclonal antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). AGE protein (ab51995), anti-MMP-1 (ab119922) and anti-TIMP-1 (ab28261) and were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). Anti-RAGE siRNA were purchased from GenePharma Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). SB203580 (inhibitor of p38 MAPK) was purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA) and PDTC (inhibitor of NF-κB) was purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Transfection reagent Lipofectamine® 2000 was purchased from Invitrogen™ Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Anti-p-p38 MAPK antibody (#9211), anti-p38 MAPK antibody (#9212), anti p-p65 NF-κB antibody (#3033) and anti p65 NF-κB antibody (#3034), were all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA).

Culture and identification of the primary fibroblasts

Human fibroblasts derived from the vaginal wall were obtained from patients suffering from POP or other diseases who required hysterectomy at the Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University. All subjects provided informed consent which was signed accompanied by an Operation Consent Form prior to surgery. Briefly, fresh vaginal wall tissue specimens from the surgical margin of the free womb were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (containing 1% penicillin, streptomycin, amphotericcin B) at 4°C for 5 min for 3 times, and digested at 37°C for 30 min with PBS containing 2% collagenase. Following isolation, the cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin, streptomycin, amphotericcin B) in 5% CO2 at 37.5°C, with replacement of the mediun every 2–3 days. HVFs were identified by anti-vimentin antibody staining and subsequently stored in liquid nitrogen for further study (19,20).

Cell counting assay

HVFs were thawed and allowed to recover for 72 h, and the cell counting per dish was affirmed by an automatic cell counting apparatus (Bio-Rad TC10TM; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) after pre-stage test. Then the cells were fixed using 10% trichloroacetic acid at 60 min at 4°C. After discarding the supernatant, the plates were washed with deionized water 5 times and dried at room temperature. Fifty microliters of sulforhodamine B solution (0.4% sulforhodamine B dissolved in 0.1% acetic acid) was added to the cells followed by 30 min of incubation. Unbound sulforhodamine B was washed with 1% acetic acid, and the plates were air-dried. One-hundred fifty microliters of 10 mM Tris-base (pH 10.5) was added to each well, and the plates were shaken gently for 20 min on a plate shaker. The absorbance of each well was determined using a microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland) at 560 nm (21,22).

Western blot analysis

Collagen I, RAGE, MMP-1, TIMP-1, p38, p-p38, p65 and p-p65 were detected in the vaginal tissues (50 mg) which were cut into small fragments and were ground by hand in a glass homogenizer on ice. Ten microliters of phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride was added followed by 1000 μl RIPA lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 2 mM NaF, 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and a protease inhibitor cocktail tablet] a few minutes later, and the proteins were separated by SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to PVDF membranes by electrophoresis. Membranes were blocked overnight at 4°C in protein blocker (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The membranes were exposed to the primary antibody at a dilution of 1:500 for 12 h at 4°C. After three washes with PBST, the membranes were hybridized with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or ant-rabbit IgG antibody. Protein bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ, USA), and relative intensities of the protein bands were analyzed using ImageJ software [National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, USA].

Measurement of mRNA expression by quantitative (real-time) PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from human vaginal wall tissues using the Total RNA Extraction Miniprep System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR were established according to the instructions provided by Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA). In brief, first-strand cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg of total RNA and the First-Strand cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen). For qPCR, 12 μl of cDNA solution was mixed with 0.5 μmol/l primers, 5 mmol/l magnesium chloride and 2 μl of Master SYBR-Green in nuclease-free water with a final volume of 20 μl. The primers used for PCR were collagen I, forward, 5′-GTGCGATGACGTGATCTG TGA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CGGTGGTTTCTTGGTCGGT-3′; MMP-1, forward, 5′-GGGGCTTTGATGTACCCTAGC-3′ and reverse, 5′-TGT CACACGCTTTTGGGGTTT-3′; TIMP-1, forward, 5′-CTT CTGCAATTCCGACCTCGT-3 ′ and reverse, 5′-ACGCTGGTATAAGGTGGTCTG-3′; RAGE, forward, 5′-GTGTCCTTCCCAACGGCTC-3′ and reverse, 5′-ATTG CCTGGCACCGGAAAA-3′. PCR amplification was performed using the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 30 sec, then 40 cycles at 95°C for 5 sec followed by elongation at 60°C for 20 sec. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an endogenous control against which the different template values were normalized. All PCR reactions were performed in duplicate. The threshold cycle (Ct) method was used for quantification. Relative quantification of the genes was performed by using the ΔΔCt approach.

Silencing of AGE, RAGE, MAPK and NF-κB cell signaling pathways using siRNA interference and inhibitors

HVFs were cultured in DMEM for 2 days post-recovery from deep freeze. The cells were treated with a RAGE-targeting siRNA expression system, which included four sequences siRNA-1, 5-GAGUAUCUGUGAAGGAACAtt-3; siRNA-2, 5-UGU UCCUUCACAGAUACUCtt-3; siRNA-3, 5-AUCUAC AAUUUCUGGCUUCtt-3; and control, 5-GUUCUCCG AACGUGUCACGUtt-3. These siRNAs were chemically synthesized, purified and annealed by GenePharma Biotechnology (Shanghai, China), which were designed to target the coding sequence of RAGE, as previously described (23–25). Both the control and vector containing siRNAs were transfected into fibroblasts using Lipofectamine 2000. The efficiency of siRNA delivery was determined by western blotting as previously described (26). SB203580 was used to inhibit MAPK at 10 μM (27), while 10 μM PDTC was used to inhibit NF-κB (28).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SE. One-way ANOVA was used to determine significant differences between the POP group and non-POP group; p<0.05 was assigned as criterion for significance for western blotting and PCR assays, using SPSS 16.0.

Results

Part 1 results

Identification of HVF cultures

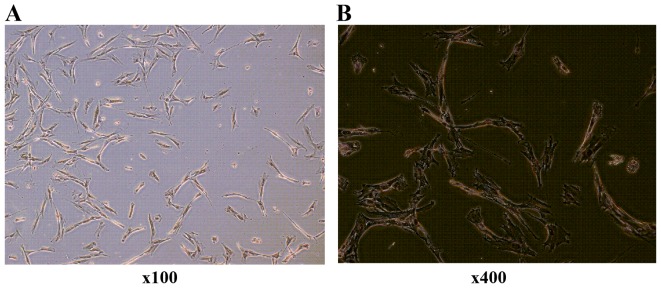

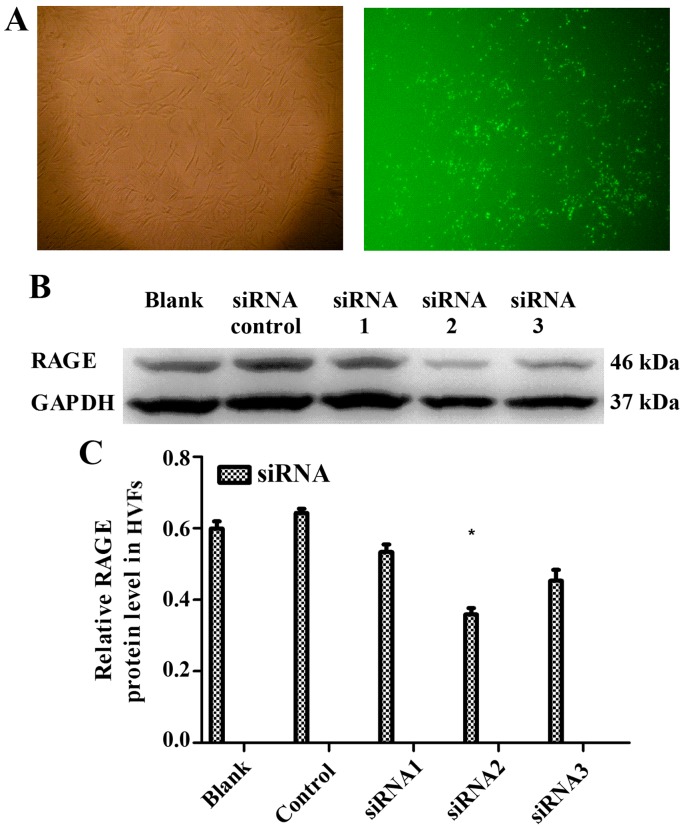

Six primary cultured HVF samples from 3 cases of POP (51, 71 and 65 years of age, respectively), and 3 cases of non-POP (55, 57 and 70 years of age, respectively), were collected. Primary cultured fibroblasts were identified by anti-vimentin antibody (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Human vaginal fibroblasts (HVFs) cultured and identified by immunohistochemistory. The primary cultured fibroblasts in vaginal wall of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) patients are shown. HVFs were identified by an antibody against anti-vimentin: (A) magnification ×100 and (B) ×400.

Impact of AGEs on HVFs

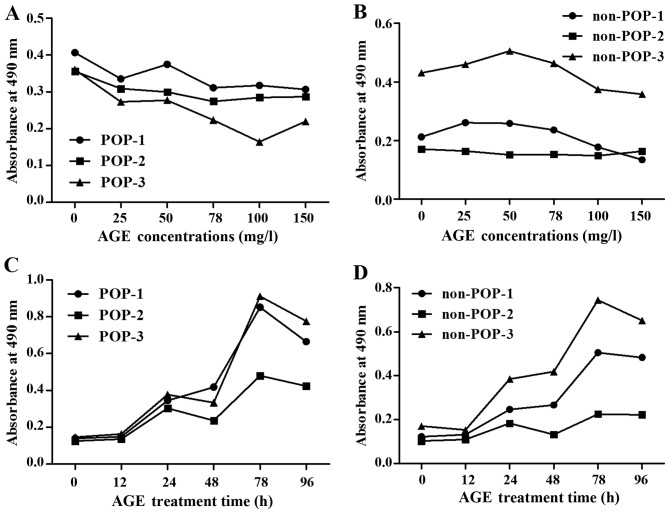

The cell counting assay demonstrated that the proliferation of the primary cultured fibroblasts was inhibited by AGE protein at various concentrations (0, 25, 50, 75, 100 and 150 mg/ml; 48 h) (Fig. 2A and B) and incubation times (0, 12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h; AGEs, 50 mg/l) (Fig. 2C and D). Proliferation of HVFs in the POP groups (25 mg/l) was more readily inhibited than that noted in the non-POP groups (25 mg/l). At the same various treatment time (0, 12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h; AGEs, 50 mg/l), the effect of AGEs on the proliferation of HVFs was analogous between the POP and non-POP groups.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the effects of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) on the proliferation of human vaginal fibroblasts (HVFs). The effects were detected by sulforhodamine B. (A and B) Proliferation curves of HVFs of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and the control group cultured under different concentrations of AGEs (at doses of 0, 25, 50, 75, 100 and 150 mg/l, 48 h). (C and D) Proliferation curves of HVFs of POP and the control group cultured for various time periods (treatment time, 0, 12, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h, at 50 mg/l). 'POP-1, 2, 3' belong to the POP groups' 'non-POP-1, 2, 3' belong to the control groups. Proliferation of the HVFs of the POP groups was more easily inhibited than that of the control groups.

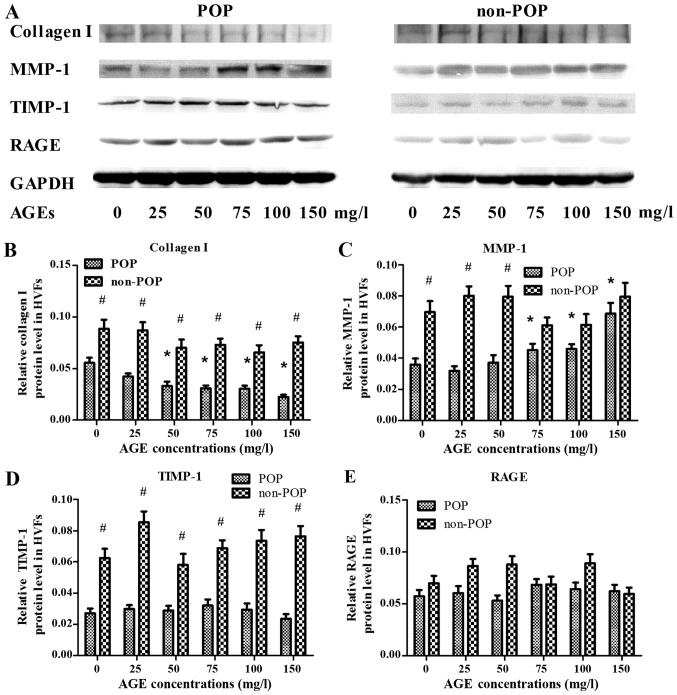

Effect of AGEs on the metabolism of collagen I in HVFs by western blotting

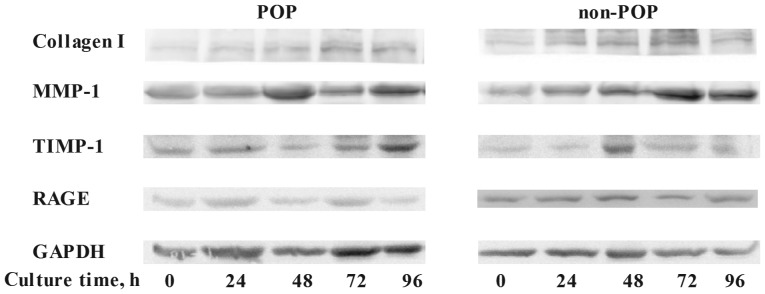

To assess the effect of AGEs on the metabolism of collagen I in HVFs, the expression levels of collagen I, MMP-1, TIMP-1 and RAGE were evaluated by western blotting (Fig. 3). Following treatment with various concentrations of AGEs (0, 25, 50, 75, 100 and 150 mg/ml; 48 h), the expression of collagen I in the POP group was decreased (inversely correlating with the concentration of AGEs) as compared to control levels (p<0.05) (Fig. 3A). In contrast to these findings, expression of MMP-1 in the POP group was increased relative to the control group (p<0.05), with increasing concentrations of AGEs (Fig. 3B). The expression of TIMP-1 in POP was lower than that in the non-POP group, and no significant changes occurred in both groups with increasing concentrations of AGEs (Fig. 3C). No significant change in the expression of RAGE was observed among the groups (Fig. 3D). Across various time-points (0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h; AGEs, 50 mg/l), there was no significant difference in the expression tendency of collagen I, MMP-1, TIMP-1 and RAGE between the POP and non-POP groups (P>0.05) (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Treatment with advanced glycation end products (AGEs) was shown to affect the expression levels of collagen I, matrix metalloproteinases-1 (MMP-1), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) and receptor of advanced glycation end products (RAGE) in human vaginal fibroblasts (HVFs) by western blot analysis. (A) Representative western blots; (B–E) Protein levels of collagen I, MMP-1, TIMP-1 and RAGE, respectively. HVFs of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and control groups were cultured under different concentrations of AGEs (at the dose of 0, 25, 50, 75, 100 and 150 mg/l, respectively, 48 h). Data are presented as the means ± SEM. *p<0.05 vs. control (0 mg/l). #P<0.05 as compared with POP group.

Figure 4.

Treatment with advanced glycation end products (AGEs) for different culture times (treatment time, 0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h) was shown to impact the protein expression levels of collagen I, matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1), tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) and receptor of advanced glycation end products (RAGE) in human vaginal fibroblasts (HVFs) by western blotting. HVFs of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and control were cultured under different culture times. The expression levels of collagen I, MMP-1, TIMP-1 and RAGE are shown.

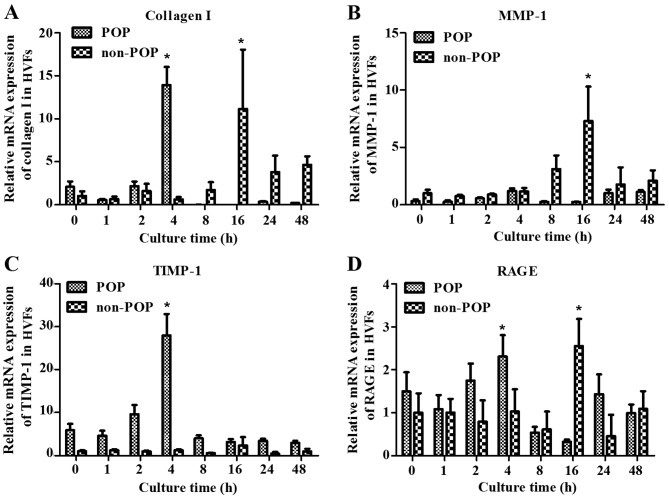

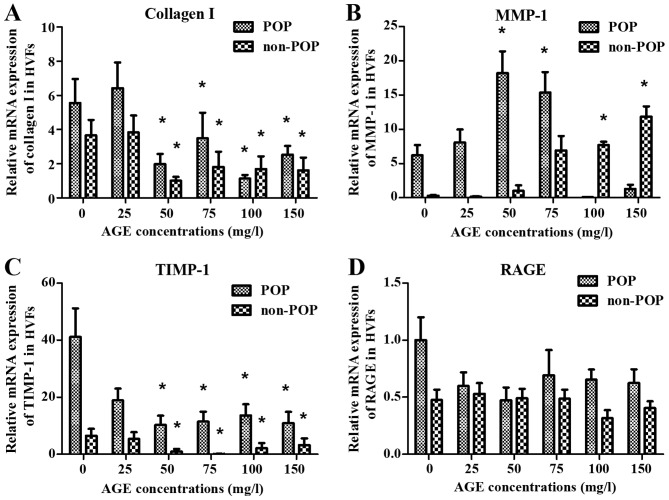

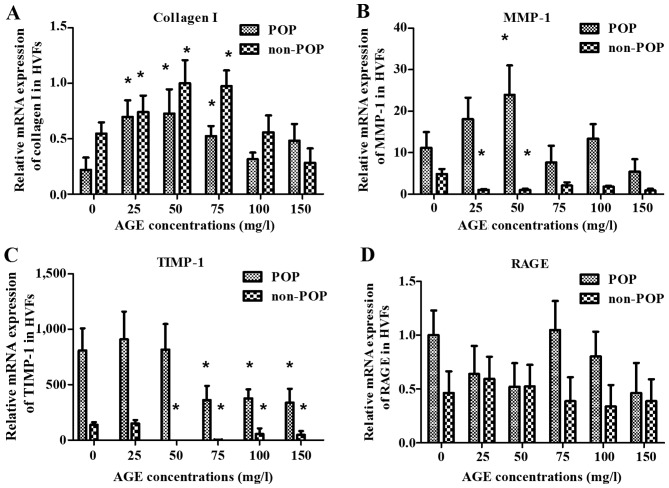

Effect of AGEs on the metabolism of collagen I in HVFs by qPCR

To examine the effect of AGEs on the metabolism of collagen, HVFs were harvested at various time-points (0, 1, 2, 4, 16, 24 and 48 h). There was a peak in RNA transcription (including collagen I, MMP-1, TIMP-1 and RAGE) detected at 4 h after treatment with the AGEs (50 mg/l) in the POP group, but also at 16 h in the control group (Fig. 5). Our results demonstrated that HVFs in the POP group were more sensitive to AGEs than the control group. We compared the difference in metabolism of collagen I under various AGE concentrations between two groups at 4 and 16 h of treatment, respectively. At 4 h, the mRNA expression of collagen I and TIMP-1 in the POP group was significantly decreased as compared to the mRNA expression in the control group (blank, AGEs, 0 mg/l) with the increasing concentration of AGEs (p<0.05) (Fig. 6A and C). However, the expression of TIMP-1 decreased more significantly in the POP than in the non-POP group. MMP-1 mRNA expression increased up to a concentration of 50 mg/l AGEs in the POP group, and then decreased (Fig. 6B). No significant changes in RAGE mRNA expression were observed between the 2 groups (Fig. 6D). At 16 h, the level of collagen I in both the POP and non-POP groups increased firstly and then decreased, respectively with the increasing concentrations of AGEs; the change tendency in the level of TIMP-1 and RAGE in the 2 groups, respectively was analogous to those changes observed at 4 h. Similarly, the mRNA expression of MMP-1 in the POP group was also similar to those results observed at 4 h (Fig. 7).

Figure 5.

Treatment with advanced glycation end products (AGEs) was shown to impact the mRNA expression of (A) collagen I, (B) matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1), (C) tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) and (D) receptor of advanced glycation end products (RAGE) by real-time PCR in human vaginal fibroblasts (HVFs). mRNA expression of collagen I, MMP-1, TIMP-1 and RAGE cultured under AGEs (50 mg/l) for different culture times in HVFs of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and non-POP groups. The culture times were 0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 24 and 48 h, respectively. Peak mRNA levels occurred at 4 h after AGE treatment in the POP groups, and 16 h in the control groups respectively. Data are presented as the means ± SEM (n=3), *p<0.06 compared to the control (blank, 0 mg/l) in their own group, respectively.

Figure 6.

Effects on the mRNA expression of (A) collagen I, (B) matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1), (C) tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) and (D) receptor of advanced glycation end products (RAGE) at 4 h after treatment with advanced glycation end products (AGEs). mRNA expression of collagen I, MMP-1, TIMP-1 and RAGE was detected by real-time PCR after human vaginal fibroblasts (HVFs) of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and control group were cultured with AGEs at different concentrations (0, 25, 50, 75, 100 and 150 mg/l, respectively). (A-D) Collagen I, MMP-1, TIMP and RAGE groups, respectively. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=3), *p<0.05 compared to the control (0 mg/l) in their own group, respectively.

Figure 7.

Effect on the mRNA expression of (A) collagen I, (B) matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1), (C) tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) and (D) receptor of advanced glycation end products (RAGE) at 16 h after treatment with advanced glycation end products (AGEs) is shown. mRNA expression of collagen I, MMP-1, TIMP-1 and RAGE was detected by real-time PCR after human vaginal fibroblasts (HVFs) of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) and control group were cultured under AGEs at different concentrations (0, 25, 50, 75, 100 and 150 mg/l, respectively). (A-D) Collagen I, MMP-1, TIMP and RAGE, respectively. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=3), *p<0.06 compared to the control (0 mg/l, respectively).

Part 2 results

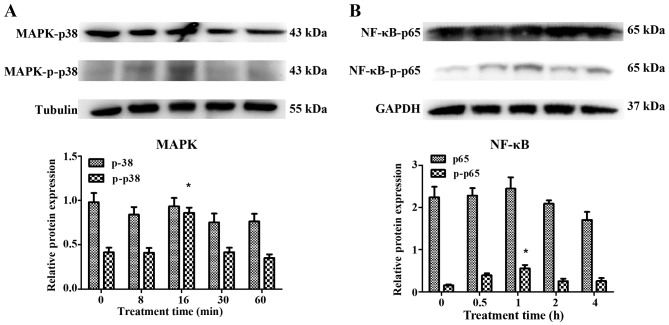

Identification and inhibition of signaling molecules of p38 MAPK, NF-κB-p65 and RAGE

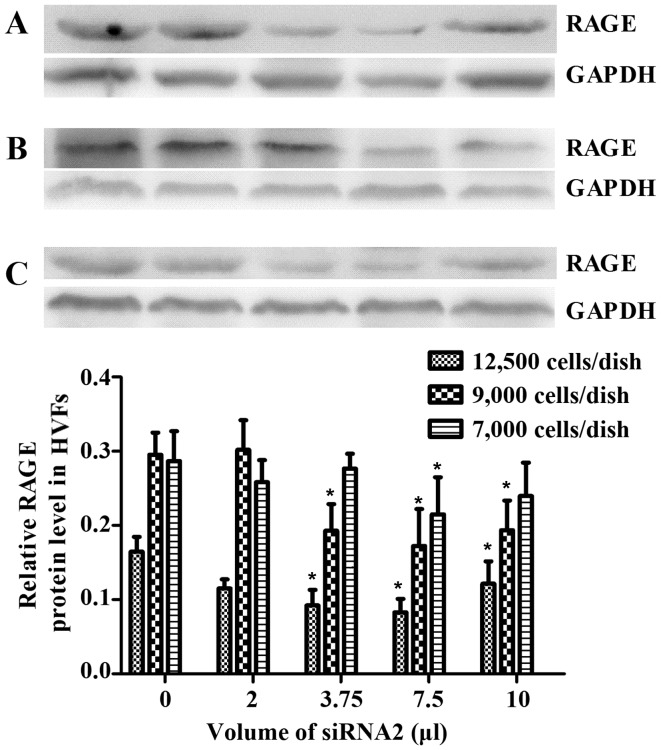

Following treatment with AGEs (50 mg/l), no significant changes were observed in the expression of p38 MAPK and NF-κB-p65, as detected by western blot analysis in the HVFs. Notably, phosphorylation products increased in the fibroblasts from patients with POP. p-p38 increased to maximum levels at 16 min post-treatment and decreased soon afterwards, while the levels of p-p65 peaked at 60 min (Fig. 8). We selected 3 siRNAs (1, 2 and 3) to silence RAGE. The blocking efficiency of siRNA2 was higher than that of the other siRNAs, and was subsequently used for all downstream applications (Fig. 9). The fibroblasts were cultured at 12,500, 9,000 and 7,000 cells/dish using a 6-well plate with 2 ml DMEM, and a series of volumes of Lipofectamine 2000 and siRNA2; the blocking efficiency of siRNA2 for RAGE was evident (p<0.05) when using a 6-well plate with 2 ml DMEM, 7.5 μl Lipofectamine 2000 and 7.5 μl siRNA2 (Fig. 10). Due to cell death by Lipofectamine 2000, which can affect sequence treatment, 9,000 cells/dish were employed appropriately.

Figure 8.

Change in (A) MAPK and (B) nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) expression in human vaginal fibroblasts (HVFs) following treatment with advanced glycation end products (AGEs) at different times (0, 8, 16, 30 and 60 min respectively for MAPK; 0, 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 h, respectively for NF-κB). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=3) (n=3). *p<0.05 compared to the control (0 min or hour, respectively).

Figure 9.

Ttransfection of siRNA with fluorescence and receptor of advanced glycation end products (RAGE) expression in human vaginal fibroblasts (HVFs) transfected with different siRNAs. (A) Images in white and green light after transfection. (B and C) Western blot and histogram of RAGE expression after transfection. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=3), *p<0.05 compared to the control (blank). All the signals were obtained from the same membrane.

Figure 10.

Quantity of siRNA2 added to dishes with different amount of cells in DMEM. Dish with (A) 12,500, (B) 9,000 and (C) 7,000 cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=3). *p<0.05 compared to the control (blank). All the signals were obtained from the same membrane.

Investigation of the RAGE, MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways in the HVFs by western blot analysis

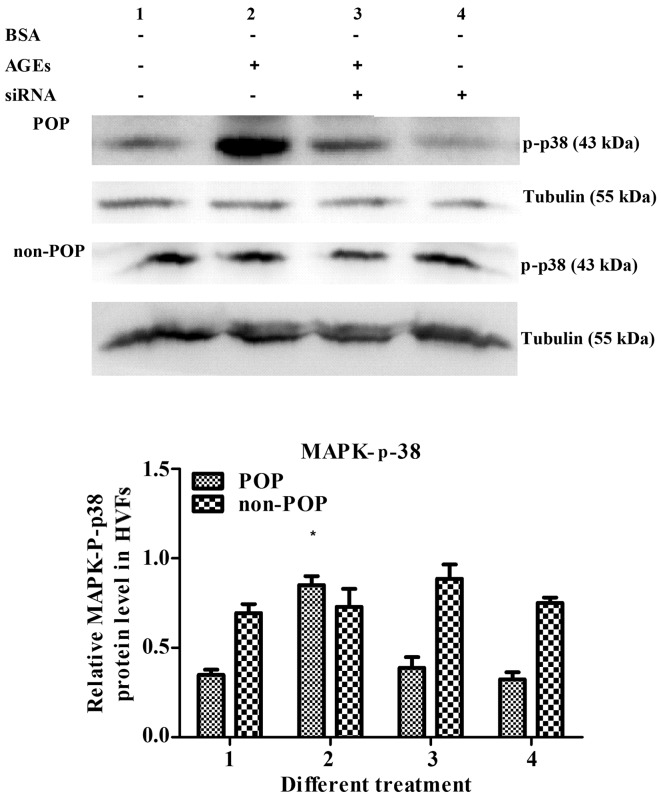

Detection of p38 MAPK

In the HVFs from patients with POP, the levels of -p-p38 MAPK increased following AGE treatment (50 mg/l); however, this effect was reversed following the inhibition of RAGE by siRNA. These results suggest that while AGEs can activate p-p38 MAPK, this process is RAGE-dependent. In HVFs from non-POP patients, the levels of p-p38 MAPK were not significantly affected by AGE treatment, which highlights a POP-specific p-p38 MAPK and AGE connection (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Detection of p-p38 MAPK after receptor of advanced glycation end products (RAGE) was blocked by siRNA for 16 min. The concentration of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) was 50 mg/l, and the quantity of siRNA was 7.5 μl/dish with 2 ml DMEM. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=3). *p<0.05 compared to the control (treatment 1, respectively). All the signals were obtained from the same membrane. The numbering of the bars (1–4) is the same as that in the top

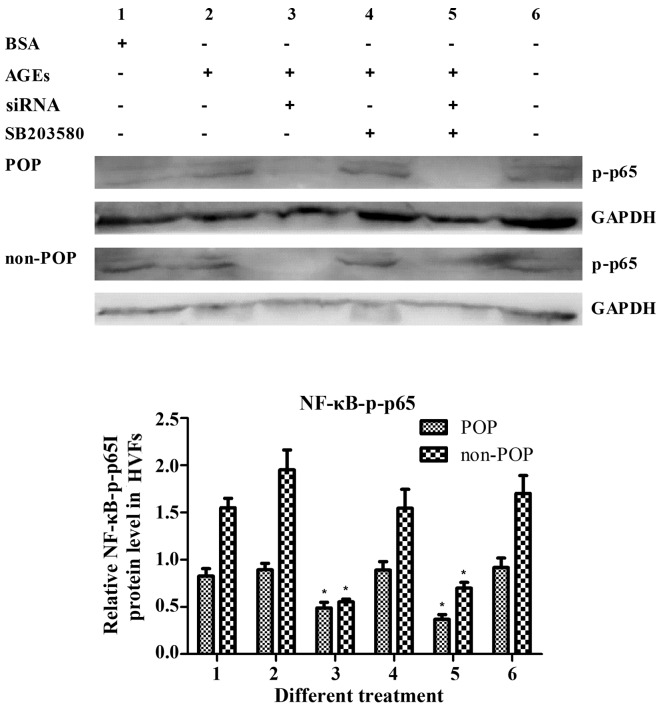

Detection of NF-κB-p-p65

In the HVFs from the POP and non-POP groups alike, the levels of NF-κB-p-p65 were increased following treatment with AGEs, and these decreased following siRNA-mediated RAGE-inhibition. These results suggest that AGE-RAGE interactions affect target proteins through NF-κB-p-p65. Notably, the p-p65 levels were not affected by the inhibition of p-p38, suggesting that NF-κB activation is not a result of a linear activation of AGE/RAGE/MAPK signaling (Fig. 12).

Figure 12.

Detection of Nf-κB-p-p65 after receptor of advanced glycation end products (RAGE) was blocked by siRNA and p38 was inhibited by SB203580 for 1 h. The concentration of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) was 50 mg/l, and SB203580 was 10 μM. Data are represented as the mean ± SEM (n=3). *p<0.05 compared to the control (treatment 1, respectively). All the signals were obtained from the same membrane. The numbering of the bars (1–6) is the same as that in the top

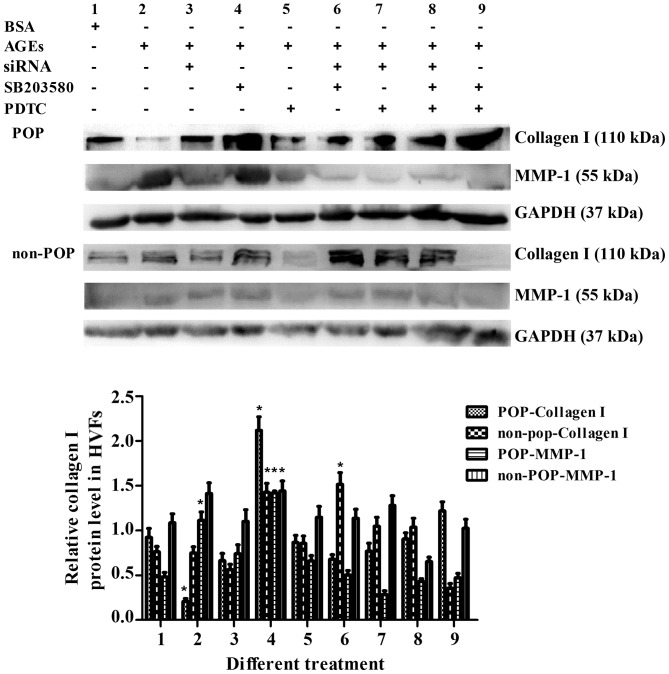

Detection of collagen I and MMP-1

Collagen I and MMP-1 were detected when RAGE, MAPK and NF-κB were blocked in various combinations. In the HVFs from patients with POP, the protein expression of collagen I decreased following AGE treatment (50 mg/l) (Fig. 13), but increased to varying degrees after the molecular or pharmacological inhibition of RAGE, MAPK or NF-κB. In the HVFs from the non-POP group, there were no significant changes observed following the same treatment modality. For MMP-1 metabolism, the opposite trend as compared to collagen I was observed (Fig. 13).

Figure 13.

Detection of collagen I and matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) after receptor of advanced glycation end products (RAGE), p38 and p65 were blocked by siRNA (7.5 μl/dish), SB203580 (20 μM) and PDTC (10 μM), respectively, or in combination. The concentration of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) was 50 mg/l, and siRNA was added after AGE treatment for 48 h. The blocking time was 48 h. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=3). The numbering of the bars (1–9) is the same as that in the top. *p<0.05 compared to the control (blank,respectively).

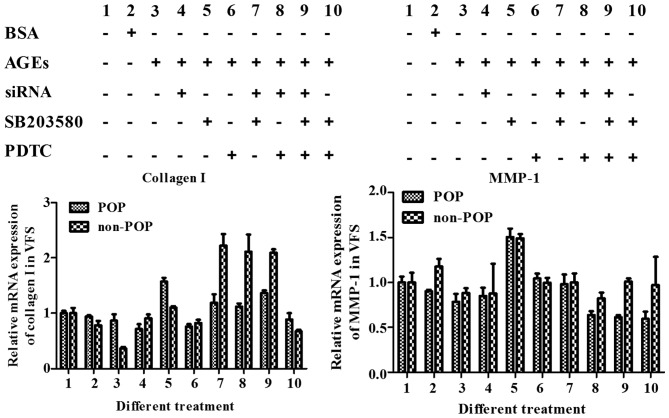

Ivestigation of the RAGE, MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways in HVFs by qPCR

To identify changes in the RAGE/MAPK/NF-κB pathway when it was affected by AGEs, the mRNA levels of target collagen I and MMP-1 were evaluated. In both the treated and control groups, collagen I mRNA levels decreased after the signaling pathways were activated by AGEs (50 mg/l) and increased following pathway (RAGE, MAPK and NF-κB) inhibition. The effect was more pronounced using combinations of inhibitors rather than a single inhibitor. For MMP-1, the mRNA expression was increased following treatment with AGEs, and decreased following treatment with the inhibitors (Fig. 14).

Figure 14.

mRNA expression of collagen I and matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) was detected by real-time PCR. Human vaginal fibroblasts (HVFs) were cultured with advanced glycation end products (AGEs) (50 mg/l) and cell signaling was blocked by siRNA, SB203580 and PDTC, respectively, or a combination. The quantity of siRNA2 [blocker of receptor of advanced glycation end products (RAGE)] was 7.5 μl/dish with 2 ml DMEM, the concentration of SB203580 (inhibitor of MAPK) was 10 μM, PDTC [inhibitor of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)] was 20 μM. siRNA was added after AGEs treating for 48 h, the block time was 24 h.

Discussion

HVFs play an important role in the pathophysiology of pelvic organ prolapse (POP), which controls the integrity of collagen, and thereby impacts the mechanical properties of the pelvic floor (8). Primary culture of HVFs is commonly used to evaluate the connective tissue of POP. In the present study, fibroblasts were successfully cultured from vaginal tissue, and then identified by anti-vimentin antibody. Considering vaginal fungi, amphotericin B was added to the DMEM culture media. This method was simple and highly efficient and the cells remained stable following recovery from long-term freeze.

Previous research has described the impacts of AGEs on fibroblast proliferation. Research has reported that AGEs promote the proliferation of fibroblasts (29), but others demonstrated that AGEs induced the apoptosis of fibroblasts or inhibited proliferation (30). In the present study, the cell counting of HVFs treated by AGEs was detected by sulforhodamine B. With increasing concentrations of AGEs, fibroblast proliferation from the POP patient group was significantly inhibited, suggesting that fibroblasts in POP were more likely to be inhibited. These results explain why the number of fibroblasts in the pelvic floor of POP is reduced (31).

In skin aging and gingival hyperplasia, AGEs can regulate the metabolism of collagen by the AGE-RAGE pathway. In this manner, synthesis of collagen I can be inhibited, degradation can be promoted, and apoptosis of fibroblasts can be induced (32,33). It still remains unclear how AGEs impact collagen metabolism in the pelvis of POP. In this study, secretion of collagen I, MMP-1 and TIMP-1 was increased gradually in both control and treated groups as time increased in accordance with a previously study (18).

Notably, the content of collagen I was decreased more gradually with increasing concentrations of AGEs in the patient group than that in the control group, which suggests that new collagen I in POP is inhibited weakening pelvic connective tissue repair. In keeping with these findings, other groups have shown that MMP-1 expression, which can accelerate collagen I degradation, is increased in pelvic tissue from POP (12,18). In this study, MMP-1 expression was more pronounced in the POP group than that in the control group. We also found that TIMP-1 levels were unaffected in both groups. This suggested that TIMP-1 could not exert a protective effect in the face of elevated MMP-1 expression. While the expression and structure of RAGE have been shown to be an important contributor to many diseases, including diabetic nephropathies (34), no changes were observed in POP vaginal tissues (18). This result suggests that AGEs regulate the metabolism of collagen through RAGE-binding. These results were further confirmed by qPCR data. Firstly, the levels of mRNA of collagen I, MMP-1 and TIMP-1 under various incubation times were tested, and peak mRNA levels were observed at 4 h in the POP group, but 16 h in the control group. This suggests that POP HVFs are more sensitive to AGEs than non-POP cells. Secondly, the level of mRNA under various concentration gradients was tested at 4 and 16 h, respectively. Irrespective of the time-point, the change in mRNA in the POP group was more readily detected than in the control. It was interesting to note that the change in TIMP-1 mRNA was similar (in trend) to that of collagen I, gradually decreasing in the face of increasing levels of AGEs. Notably, in spite of these trends, TIMP-1 protein expression remained stable suggesting a possible mechanism dependent on post-translational modifications. Similarly, RAGE mRNA and protein levels were unaffected suggesting that AGEs function through an AGEs/RAGE-dependent pathway.

Characterization of AGE/RAGE pathway activation and downstream signaling was an important objective in this study. Previous studies have suggested that AGE/RAGE signaling involves numerous signaling pathways including: eNOS, NAD (P) H-ROS, p21RAS-MAPK, p38 MAPK, Cdc42-Rac and NF-κB. We chose to specifically evaluate p38 MAPK and NF-κB-p65 signaling pathways (35,39). Phosphorylation targets MAPK p39 and NF-κB-p65 increased substantially following treatment with AGEs, but the non-phosphorylated products remained stable, indicating that phosphorylated products participate in the metabolism of collagen I.

To characterize downstream cell signaling pathways, we inhibited specific cell signaling molecules alone or in combination. We inhibited RAGE using an siRNA-based strategy, validating our results using western blotting. Of the three siRNAs evaluated, siRNA2 was most effective. Furthermore, we optimized the transfection conditions. Specifically we addressed a number of concerns including the number of cells and the amount of transfection reagent both of which greatly impact the transfection efficiency and cell viability, respectively. In contrast to this siRNA-based approach we pharmacologically inhibited MAPK (SB203580) and NF-κB (PDTC) and validating the effectiveness of this approach by western blotting. In the POP group but not the control cells, p-p38 was activated by AGEs but this effect was reversed by siRNA. p-p65 could not be activated after RAGE was inhibited, but was activated after p-p38 was inhibited in the two groups. These results clarify that AGEs can activate NF-κB through RAGE and downstream cell molecules besides p-p38 in POP-derived cells. We also found that both collagen I and MMP-1 expression could be modulated by activation and inhibition of these pathways. When treatment with AGEs was utilized, the expression of collagen I was inhibited, while MMP-1 was activated; when RAGE was silenced by siRNA and p-p38 was blocked by SB203580, the suppression of collagen I was recovered, but MMP-1 was inhibited; and the control group remained stable.

In the last part of this study, the mRNA synthesis of target proteins of MMP-1 and collagen I was detected after three signaling molecules were blocked in various combinations. General speaking, the mRNA expression trends matched those observations made at the protein level by western blotting. On the one hand, the result of PCR highlighted the impact of AGEs on the AGE, RAGE, MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways which are involved in the synthesis and degradation metabolism of collagen, and may explain the reason why collagen I was decreased in the vaginal tissue of POP. On the other hand, there are multiple factors which can affect the complicated process from binding of receptor to protein secretion, and therefore innumerable additional factors may have confounded/impacted the interpretation of these results.

In conclusion, AGEs can affect the metabolism of collagen through RAGE, but not directly through changes in expression or structure. AGEs activate p-p38 MAPK and NF-κB-p-p65 pathways, thereby regulating collagen metabolism, although other pathways may also participate. Taken together, our study provides enhanced understanding of the mechanism through which AGEs contribute to collagen metabolism in pelvic tissue of POP and the pathophysiology of POP.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (no. 124119a500); the General Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81671439).

References

- 1.Chow D, Rodríguez LV. Epidemiology and prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse. Curr Opin Urol. 2013;23:293–298. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3283619ed0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun B, Zhou L, Wen Y, Wang C, Baer TM, Pera RR, Chen B. Proliferative behavior of vaginal fibroblasts from women with pelvic organ prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;183:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2014.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruiz-Zapata AM, Kerkhof MH, Zandieh-Doulabi B, Brölmann HA, Smit TH, Helder MN. Functional characteristics of vaginal fibroblastic cells from premenopausal women with pelvic organ prolapse. Mol Hum Reprod. 2014;20:1135–1143. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gau078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen HY, Lu Y, Qi Y, Bai WP, Liao QP. Relationship between the expressions of mitofusin-2 and procollagen in uterosacral ligament fibroblasts of postmenopausal patients with pelvic organ prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014;174:141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanta J. Collagen matrix as a tool in studying fibroblastic cell behavior. Cell Adh Migr. 2015;9:308–316. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2015.1005469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim VF, Khoo JK, Wong V, Moore KH. Recent studies of genetic dysfunction in pelvic organ prolapse: the role of collagen defects. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;54:198–205. doi: 10.1111/ajo.12169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson SR, Avery NC, Tarlton JF, Eckford SD, Abrams P, Bailey AJ. Changes in metabolism of collagen in genitourinary prolapsed. Lancet. 1996;347:1658–1661. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)91489-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han L, Wang L, Wang Q, Li H, Zang H. Association between pelvic organ prolapsed and stress urinary incontinence with collagen. Exp Ther Med. 2014;7:1337–1341. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.1563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerkhof MH, Ruiz-Zapata AM, Bril H, Bleeker MC, Belien JA, Stoop R, Helder MN. Changes in tissue composition of the vaginal wall of premenopausal women with prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;210:168.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.10.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vulic M, Strinic T, Tomic S, Capkun V, Jakus IA, Ivica S. Difference in expression of collagen type I and matrix metalloproteinase-1 in uterosacral ligaments of women with and without pelvic organ prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;155:225–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dviri M, Leron E, Dreiher J, Mazor M, Shaco-Levy R. Increased matrix metalloproteinases-1,-9 in the uterosacral ligaments and vaginal tissue from women with pelvic organ prolapse. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;156:113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, Li Y, Chen J, Guo X, Guan H, Li C. Differential expression profiling of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in females with or without pelvic organ prolapse. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10:2004–2008. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willett TL, Pasquale J, Grynpas MD. Collagen modifications in postmenopausal osteoporosis: Advanced glycation endproducts may affect bone volume, structure and quality. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2014;12:329–337. doi: 10.1007/s11914-014-0214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ajith TA, Vinodkumar P. Advanced glycation end products: Association with the pathogenesis of diseases and the current therapeutic advances. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2016;11:118–127. doi: 10.2174/1574884711666160511150028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamagishi S, Fukami K, Matsui T. Evaluation of tissue accumulation levels of advanced glycation end products by skin autofluorescence: A novel marker of vascular complications in high-risk patients for cardiovascular disease. Int J Cardiol. 2015;185:263–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu H, Jiang H, Ren H, Hu X, Wang X, Han C. AGEs and chronic subclinical inflammation in diabetes: Disorders of immune system. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2015;31:127–137. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gkogkolou P, Böhm M. Advanced glycation end products: Key players in skin aging? Dermatoendocrinol. 2012;4:259–270. doi: 10.4161/derm.22028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y, Huang J, Hu C, Hua K. Relationship of advanced glycation end products and their receptor to pelvic organ prolapse. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:2288–2299. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.El Mourabit H, Loeuillard E, Lemoinne S, Cadoret A, Housset C. Culture model of rat portal myofibroblasts. Front Physiol. 2016;7:120. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2016.00120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olszewski S, Olszewska E, Popko J, Poskrobko E, Sierakowski S, Zwierz K. Fibroblast-like synovial cells in rheumatoid arthritis - the impact of infliximab on hexosaminidase activity. Adv Clin Exp Med. 2015;24:807–813. doi: 10.17219/acem/27302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yong WK, Ho YF, Malek SN. Xanthohumol induces apoptosis and S phase cell cycle arrest in A549 non-small cell lung cancer cells. Pharmacogn Mag. 2015;11(Suppl 2):S275–S283. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.166069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nájera-Martínez M, García-Latorre EA, Reyes-Maldonado E. Halomethane-induced cytotoxicity and cell proliferation in human lung MRC-5 fibroblasts and NL20-TA epithelial cells. Inhal Toxicol. 2012;24:762–773. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2012.716871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radia AM, Yaser AM, Ma X, Zhang J, Yang C, Dong Q, Rong P, Ye B, Liu S, Wang W. Specific siRNA targeting receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) decreases proliferation in human breast cancer cell lines. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:7959–7978. doi: 10.3390/ijms14047959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monden M, Koyama H, Otsuka Y, Morioka T, Mori K, Shoji T, Mima Y, Motoyama K, Fukumoto S, Shioi A, et al. Receptor for advanced glycation end products regulates adipocyte hypertrophy and insulin sensitivity in mice: Involvement of Toll-like receptor 2. Diabetes. 2013;62:478–489. doi: 10.2337/db11-1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Volz HC, Laohachewin D, Seidel C, Lasitschka F, Keilbach K, Wienbrandt AR, Andrassy J, Bierhaus A, Kaya Z, Katus HA, et al. S100A8/A9 aggravates post-ischemic heart failure through activation of RAGE-dependent NF-κB signaling. Basic Res Cardiol. 2012;107:250. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0250-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angiolilli C, Kabala PA, Grabiec AM, Van Baarsen IM, Ferguson BS, García S, Malvar Fernandez B, McKinsey TA, Tak PP, Fossati G, et al. Histone deacetylase 3 regulates the inflammatory gene expression programme of rheumatoid arthritis fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:277–285. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-209064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H, Liu A, Shi C, Li B. Curcumin suppresses transforming growth factor-β1-induced cardiac fibroblast differentiation via inhibition of Smad-2 and p38 MAPK signaling pathways. Exp Ther Med. 2016;11:998–1004. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.2969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Su C, Chen M, Huang H, Lin J. Testosterone enhances lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-6 and macrophage chemotactic protein-1 expression by activating the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2/nuclear factor-κB signalling pathways in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:696–704. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marelli B, Le Nihouannen D, Hacking SA, Tran S, Li J, Murshed M, Doillon CJ, Ghezzi CE, Zhang YL, Nazhat SN, Barralet JE. Newly identified interfibrillar collagen crosslinking suppresses cell proliferation and remodelling. Biomaterials. 2015;54:126–135. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li W, Xu Q, Deng Y, Yang Z, Xing S, Zhao X, Zhu P, Wang X, He Z, Gao Y. High-mobility group box 1 accelerates lipopolysaccharide-induced lung fibroblast proliferation in vitro: Involvement of the NF-κB signaling pathway. Lab Invest. 2015;95:635–647. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2015.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kökçü A, Yanik F, Cetinkaya M, Alper T, Kandemir B, Malatyalioglu E. Histopathological evaluation of the connective tissue of the vaginal fascia and the uterine ligaments inwomen with and without pelvic relaxation. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2002;266:75–78. doi: 10.1007/s004040100194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niu Y, Xie T, Ge K, Lin Y, Lu S. Effects of extracellular matrix glycosylation on proliferation and apoptosis of human dermal fibroblasts via the receptor for advanced glycosylated end products. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:344–351. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31816a8c5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbass MM, Korany NS, Salama AH, Dmytryk JJ, Safiejko-Mroczka B. The relationship between receptor for advanced glycation end products expression and the severity of periodontal disease in the gingiva of diabetic and non diabetic periodontitis patients. Arch Oral Biol. 2012;57:1342–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsui T, Nakashima S, Nishino Y, Ojima A, Nakamura N, Arima K, Fukami K, Okuda S, Yamagishi S. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 deficiency protects against experimental diabetic nephropathy partly by blocking the advanced glycation end products-receptor axis. Lab Invest. 2015;95:525–533. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2015.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Giridharan VV, Thandavarayan RA, Arumugam S, Mizuno M, Nawa H, Suzuki K, Ko KM, Krishnamurthy P, Watanabe K, Konishi T. Schisandrin B ameliorates ICV-infused amyloid β induced oxidative stress and neuronal dysfunction through inhibiting RAGE/NF-κB/MAPK and up-regulating HSP/Beclin expression. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142483. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu Q, Li S, Li X, Sui Y, Yang Y, Dong L, Xie B, Sun Z. Inhibition of advanced glycation endproduct formation by lotus seedpod oligomeric procyanidins through RAGE-MAPK signaling and NF-κB activation in high-fat-diet rats. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:6989–6998. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b01082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Medeiros MC, Frasnelli SC, Bastos AS, Orrico SR, Rossa C., Jr Modulation of cell proliferation, survival and gene expression by RAGE and TLR signaling in cells of the innate and adaptive immune response: Role of p38 MAPK and NF-κB. J Appl Oral Sci. 2014;22:185–193. doi: 10.1590/1678-775720130593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He ZW, Qin YH, Wang ZW, Chen Y, Shen Q, Dai SM. HMGB1 acts in synergy with lipopolysaccharide in activating rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts via p38 MAPK and NF-κB signaling pathways. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:596716. doi: 10.1155/2013/596716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Bittencourt Pasquali MA, Gelain DP, Zeidán-Chuliá F, Pires AS, Gasparotto J, Terra SR, Moreira JC. Vitamin A (retinol) downregulates the receptor for advanced glycation endproducts (RAGE) by oxidant-dependent activation of p38 MAPK and NF-κB in human lung cancer A549 cells. Cell Signal. 2013;25:939–954. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]