Abstract

Avian leukosis virus induces tumors in chickens by integrating into the genome and altering expression of nearby genes. Thus, ALV can be used as an insertional mutagenesis tool to identify novel genes involved in tumorigenesis. Deep sequencing analysis of viral integration sites has identified CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 as common integration sites in ALV-induced B-cell lymphomas, suggesting a potential role in driving oncogenesis. We show that in tumors with integrations in these genes, the viral promoter is driving the expression of a truncated fusion transcript. Overexpression in cultured chick embryo fibroblasts reveals that CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 have oncogenic properties, including promoting cell migration. We also show that CTDSPL2 has a previously uncharacterized role in protecting cells from apoptosis induced by oxidative stress. Further, the truncated viral fusion transcripts of both CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 promote immortalization in primary cell culture.

Keywords: CTD small phosphatase like proteins, ALV, lymphoma, immortalization, migration

INTRODUCTION

Avian leukosis virus (ALV) is a simple retrovirus that induces tumorigenesis by integrating into the host genome and altering expression of cellular genes [1]. ALV typically induces B-cell lymphomas but has been shown to induce various other neoplasms less frequently [2]. Insertion of the proviral genome into the host cell genome can alter host gene expression in a number of ways. The long terminal repeats (LTRs) contain strong promoter and enhancer elements that can promote nearby gene expression. In addition, the proviral genome can integrate within a gene and disrupt expression or generate truncated protein products with altered functions [3]. ALV integrates relatively randomly into the host genome and thus, is a good tool for insertional mutagenesis screens to identify novel genes involved in cancer [4]. Integrations into a number of proto-oncogenes, including MYC, MYB, TERT, mir-155, MET and EGFR, have been seen in past screens [1, 5–9].

Our lab has previously identified CTDSPL (C-terminal domain small phosphatase-like) and CTDSPL2 (C-terminal domain small phosphatase-like 2) as common integration sites in ALV-induced B-cell lymphomas [10]. The recurrence and selection of integrations within these genes in tumors suggests that they may be involved in driving tumorigenesis. The CTDSP family of proteins consists of CTDSP1, CTDSP2, CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 proteins, all of which contain a catalytic FCP1 (F-cell production 1) homology domain that functions as a phosphatase [11]. The CTDSP family has been shown to dephosphorylate the C-terminal domain (CTD) of RNA polymerase II in vitro [11, 12]. Through this function, this family of proteins is proposed to be important for transcriptional regulation. Most family members preferentially dephosphorylate Ser5 of the CTD and thus control the transition from initiation to processive transcription elongation [11, 12]. CTDSP1, CTDSP2 and CTDSPL have also been shown to play a role in gene silencing, most notably of neuronal gene expression, through interaction with the REST complex [12–14].

The CTDSP proteins are able to act on additional targets as well. For instance, CTDSP1/2/L proteins have been shown to induce TGF-β signaling and attenuate BMP signaling [15, 16]. CTDSP1 also stabilizes SNAIL and C-MYC proteins by dephosphorylating a key serine residue [17, 18]. Further, CTDSP1/2/L genes have all been found to contain an intronic microRNA that belongs to the miR-26 family. These miRNAs have been shown to act synergistically with the CTDSP1 and CTDSPL proteins to dephosphorylate, and thus activate, pRb and block the G1/S cell cycle transition [19]. CTDSP2 has also been shown to inhibit cell cycle progression independently by activating Ras and p21 [20].

Due to involvement in these pathways, it comes as no surprise that the CTDSP1/2/L and the miR-26 family have been implicated in tumorigenesis. CTDSPL has been characterized as a tumor suppressor gene that is frequently deleted or mutated in many major epithelial cancers such as lung, renal cell and breast carcinoma [19, 21–23]. Further, all 3 proteins are down-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines [19]. Comparatively, little is known about CTDSPL2. It has been shown to play a role in erythroid differentiation and BMP signaling [24, 25]. However, CTDSPL2 has not been previously linked to tumorigenesis.

In this work, we characterize CTDSPL2 as a novel gene involved in oncogenesis and further characterize the role of CTDSPL. Specifically, we investigate the function of viral induced truncations of both genes in cancer. Overexpression of CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 leads to changes in expression of ribosomal genes and genes involved in cellular migration and metabolism. We show that overexpression of both CTDSPL and CTDPSL2 causes accelerated cellular migration in primary cell culture. Interestingly, expression of CTDSPL2, but not CTDSPL, protects cells from apoptosis induced by oxidative stress, indicating that the two genes may not be redundant. Importantly, the truncated viral fusion transcripts of both CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 promote immortalization when overexpressed in primary cell culture.

RESULTS

CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 are common integration sites in ALV-induced B-cell lymphomas

High throughput sequencing was used to identify retroviral integration sites in ALV-induced B-cell lymphomas [10]. Integration sites that are overrepresented in the sequencing data, either because of clonal expansion or because the gene is a common integration site between tumors, were selected for and therefore believed to be important in tumorigenesis.

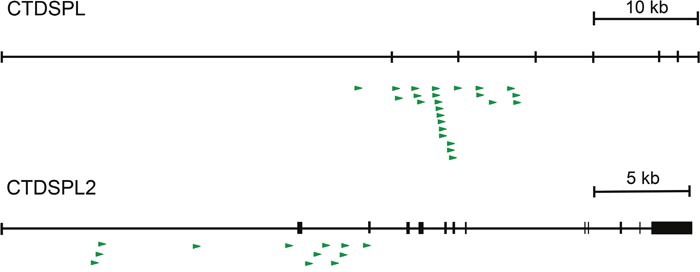

CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 were identified to be common integration sites previously [10]. In this study we have expanded our analysis and observed 23 unique clonally expanded integrations in CTDSPL in 12 tumors from 7 birds. All expanded integrations are in the same transcriptional orientation as CTDSPL and fall upstream of exon 4 (Figure 1; Supplementary Table 1). In addition, thirteen unique expanded integrations were detected in CTDSPL2 in 7 tumors from 4 birds. All expanded integrations in the gene are in the same transcriptional orientation as CTDSPL2 and fall upstream of exon 3 (Figure 1; Supplementary Table 1). No expanded integrations into either gene were observed in non-tumors. Interestingly, we did not observe integration into other CTDSP family members.

Figure 1. CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 are common integration sites in ALV-induced B-cell lymphomas.

A schematic of retroviral integrations into both CTDSPL and CTDSPL2. Each integration is depicted as an arrow with the base of the arrow representing the site of integration. Direction of the arrow indicates the orientation of the retroviral integration with respect to transcription of the gene; all are in the sense orientation. There are 23 unique expanded integrations in CTDSPL, all of which fall upstream of exon 4. There are 13 unique expanded integrations in CTDSPL2 upstream of exon 3.

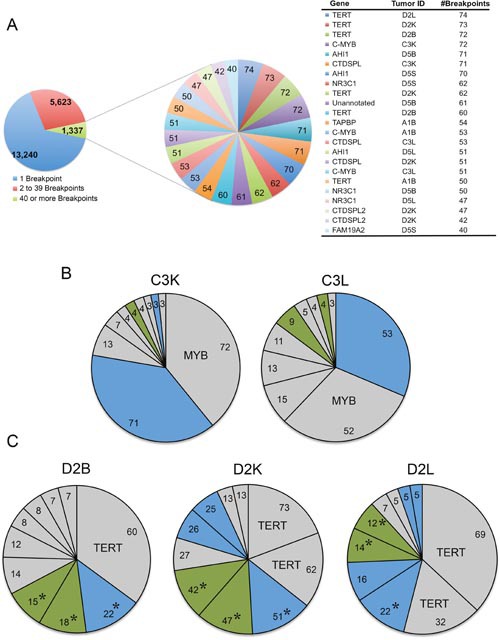

Activation of CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 are likely early events in tumorigenesis

A number of integration sites in the CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 genes were found to be highly clonally expanded. Clonal expansion of a specific integration within a tumor was estimated via quantitation of sonication breakpoints as described previously [10]. The highest breakpoint integrations from tumors carrying CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 integrations are shown in a composite pie chart in Figure 2A. In some individual tumors, these integrations were amongst the most dominant, expanded integrations (Figure 2B). This suggests that these integrations occurred early in tumorigenesis and were expanded as the tumor progressed.

Figure 2. Viral integrations into CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 are an early event in tumorigenesis.

(A) A composite pie chart of 11 tumors containing clonally expanded integrations in either CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 is shown. In this tumor set, there were 14,879 unique integrations represented by 20,200 total breakpoints. Integrations having 40 or more breakpoints are depicted in a separate composite pie chart with individual integrations as a single “slice” of the pie chart, weighted by number of breakpoints. There are 23 integrations with 40 or more breakpoints. Of these top clonally expanded integrations, 3 are in CTDSPL and 2 are in CTDSPL2. (B) CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 are dominant integrations in some individual tumors. The top 10 clonally expanded integrations are shown for representative tumors (C3L and C3K). In these cases CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 are among the most dominant integrations. CTDSPL integrations are indicated in blue, CTDSPL2 integrations are indicated in green. Top integrations are labeled. (C) Primary (bursa) and secondary (kidney and liver) tumors from the same bird (D2) have identical integrations in CTDSPL and CTDSPL2. CTDSPL integrations are indicated in blue, CTDSPL2 integrations are indicated in green. The most dominant integrations are labeled. Identical integrations in each tumor are indicated with *. These integrations are clonally expanded in all cases, comprising a comparable proportion of the total tumor breakpoints. This suggests that these integrations occurred early in tumorigenesis, within the bursa and subsequently metastasized to these secondary sites.

Identical integration sites within both CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 genes were identified in primary (bursal) and secondary (liver and kidney) tumors found in the same bird (Figure 2C). The presence of identical integration sites also indicates that these integrations likely occurred early in tumorigenesis prior to metastasis. The primary bursal tumor then metastasized to various locations including the liver, kidney and spleen, causing the clonal expansion of the integrated provirus in different secondary tumors. Interestingly, integrations in CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 frequently occur in the same tumor. For instance, primary and secondary tumors in birds C3 and D2 have many of the most clonally expanded integrations in both genes (Supplementary Table 1).

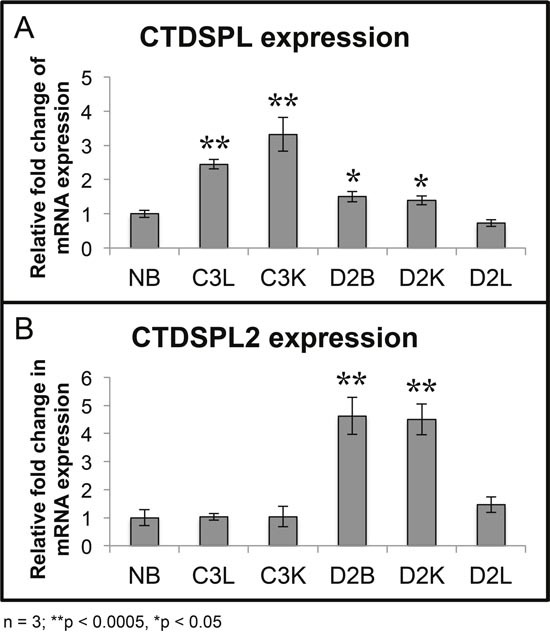

Viral integrations in CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 drive the overexpression of genes

Quantitative RT-PCR verified that relative to normal bursa, levels of both CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 mRNA were elevated in the tumors with highly clonally expanded integrations in these genes (Figure 3A). For instance, C3L and C3K had a co-dominant integration in CTDSPL (Figure 2B) and expression of this gene was significantly elevated by approximately 2.5- to 3.5-fold respectively. Similarly, D2B and D2K had some of the most highly expanded integrations in CTDSPL2 and we observed a corresponding 4.5 fold increase in expression (Figure 3B). It is interesting to note that tumors in D2 have clonally expanded integrations in both genes but only one of the genes is overexpressed.

Figure 3. Tumors with expanded integrations in CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 overexpress transcripts.

(A) qPCR was performed from tumor cDNA for either CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 and normalized to a housekeeping gene, GAPDH. Fold change in mRNA expression is depicted relative to expression levels in normal bursa (NB). Tumors with the most highly expanded integrations in CTDSPL significantly overexpress CTDSPL mRNA by 3- to 3.5- fold (C3L and C3K). (B) Likewise, those tumors with the most expanded integrations in CTDSPL2 also have a 4.5-fold increase in CTDSPL2 mRNA expression (D2B and D2K).

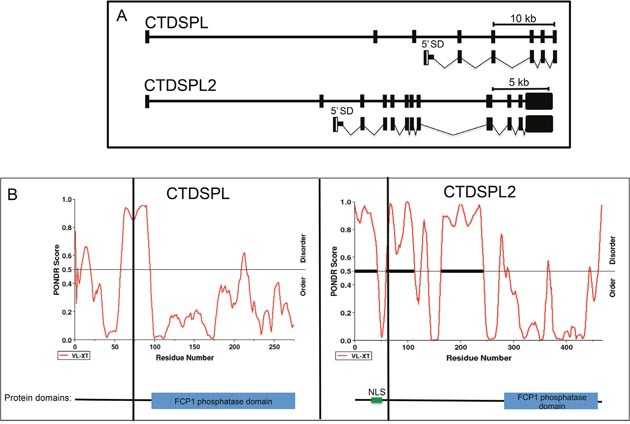

Integrations in CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 generate truncated fusion transcripts

To determine the mechanism by which the viral integrations are disrupting CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 expression, we performed RT-PCR to detect any potential viral fusion transcripts. We found that integrations in CTDSPL were driving the expression of a fusion transcript from the viral promoter with splicing occurring from the canonical splice donor site in gag to the splice acceptor site of exon 4 of the CTDSPL mRNA removing 77 amino acids from the N-terminus of the protein (Figure 4A). Integrations in CTDSPL2 were driving expression of a fusion transcript from the viral promoter with splicing occurring from the canonical splice donor site in gag to the splice acceptor site of exon 3 of CTDSPL2 removing 63 amino acids from the N-terminus of the protein (Figure 4A). In both cases, the viral start codon was in frame with the open reading frames and would add 6 amino acids of ALV gag at the N-terminus of the fusion protein. The truncation did not affect the catalytic phosphatase domain of either protein but did remove a portion of a predicted intrinsically disordered region of both proteins (Figure 4B). In the case of CTDPSL2, the truncation also removed a predicted nuclear localization signal (NLS; Figure 4B).

Figure 4. CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 transcript truncations induced by viral integrations.

(A) Schematic of truncated transcripts expressed from integrations in CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 as detected by RT-PCR. The promoter in the 5′ LTR of ALV drives expression of truncated transcripts. Transcripts contain the gag leader sequence spliced from the canonical splice donor site (5′ SD) into either exon 4 of CTDSPL or exon 3 of CTDSPL2. The ORF is not disrupted in either truncated transcript. (B) PONDR plots of CTDSPL and CTDSPL2. PONDR was used to predict intrinsically disordered regions of both CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 proteins [38]. PONDR VL-XT score is indicated by red line. Threshold for disorder is set at 0.5 and indicated by a horizontal line. Significant stretches of disorder are indicated by thick black horizontal lines. The N-terminal portion of CTDSPL2 is significantly more disordered than CTDSPL. Truncations induced by viral integrations are indicated by a vertical black line. In both CTDSPL and CTDSPL2, the truncations remove a portion of the predicted disordered region. For CTDSPL2, the truncation also removes a predicted nuclear localization signal (NLS). For reference the catalytic domain (blue box) and NLS (green) are shown in a schematic representation of CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 at the bottom of PONDR plots.

CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 induce expression changes in genes implicated in cellular migration, translation, alternative splicing and oxidative phosphorylation

To better characterize the role of CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 in ALV-induced B-cell lymphomas, we generated truncated transcripts in viral vectors to mimic those being expressed in tumors. Chick embryo fibroblasts (CEF) were infected with retroviral vectors (RCAS(A)) carrying either the truncated or full-length transcript of either CTDSPL or CTDSPL2. Transcripts were overexpressed approximately 100-fold relative to wild type CEF expression.

Both CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 are believed to act on the CTD of RNA polymerase II to regulate gene expression [11]. We reasoned that overexpression of these genes by viral integration may be affecting downstream gene expression. To identify changes in gene expression, RNA-seq analysis was performed on cells overexpressing truncated or full length CTDSPL or CTDSPL2. Cufflinks was used to detect genes differentially expressed in cells carrying a CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 construct relative to cells infected with an empty retroviral construct.

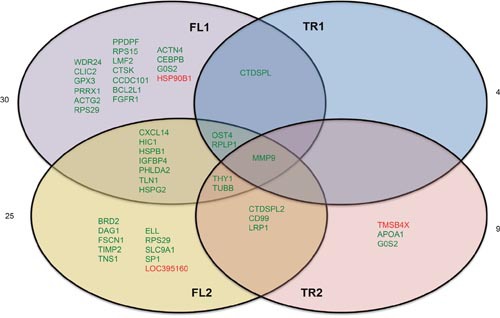

We observed between 4 and 30 genes differentially expressed in each condition (Figure 5, Supplementary Table 2). There was very little overlap in differentially expressed genes between overexpression conditions. MMP9, or matrix metalloproteinase-9 is the only gene that was significantly deregulated by overexpression of all constructs. Cells expressing full length CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 had the most similar changes in gene expression profiles with approximately 1/3 of the deregulated genes overlapping between the two conditions, suggesting that they may play partially redundant roles.

Figure 5. Genes differentially expressed by overexpression of CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 full length or truncated transcripts.

RNA-seq analysis of CEF cells overexpressing truncated or full length CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 revealed a number of significantly overexpressed genes. Venn diagram depicting deregulation of gene expression by overexpression of truncated or full length CTDSPL or CTDSPL2. Genes shown in green were significantly upregulated relative to cells infected with an empty viral vector. Genes shown in red were significantly downregulated. Fold change in expression for each gene is given in Supplementary Table 2.

In order to determine differences in gene regulation induced by truncation of CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 genes, we performed a GO analysis of genes differentially expressed between the full length and truncated form of both CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 separately (Table 1; Supplementary Table 3). Differentially regulated genes between truncated and full length CTDSPL were enriched for genes involved in mitochondria, oxidative phosphorylation, alternative splicing and Sp1 targets. Mitochondrial genes as well as genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation were found to be upregulated in the cells expressing truncated CTDSPL. Sp1 target genes and genes involved in alternative splicing were found to be downregulated in cells expressing the truncated construct.

Table 1. Gene ontology (GO) analysis of genes differentially regulated by overexpression of truncated versus full length CTDSPL or CTDSPL2.

| GO term | P-value |

|---|---|

| Enrichment in genes upregulated in TR1 vs. FL1 | |

| Metabolism | 0.00000125 |

| Oxidative phosphorylation | 0.00000301 |

| Ribosome | 0.000927 |

| Adherens/anchoring junctions | 0.00471 |

| Factor: E2F | 0.00997 |

| Enrichment in genes downregulated in TR1 vs. FL1 | |

| Focal adhesion | 6.47×10−10 |

| Factor: ETF | 0.00000002 |

| Factor: Sp1 | 0.00000026 |

| Factor: E2F-3 | 0.00000897 |

| Cell migration | 0.000286 |

| Alternative splicing | 0.0000654 |

| Enrichment in genes upregulated in TR2 vs. FL2 | |

| Ribosome | 0.046 |

| Cell adhesion | 0.05 |

| Enrichment in genes downregulated in TR2 vs. FL2 | |

| Focal adhesion | 0.0062 |

| Ribsomal protein | 0.0157 |

In both cases an enrichment of genes involved in cellular locomotion or focal adhesion, E2F targets and ribosomal genes were observed. There was no clear trend of upregulation or downregulation of the genes in these GO categories. There was little overlap in affected genes between full length and truncated constructs. Expression of truncated CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 induced fewer changes in gene expression than either full-length construct indicating that the truncation may result in a partial loss of function.

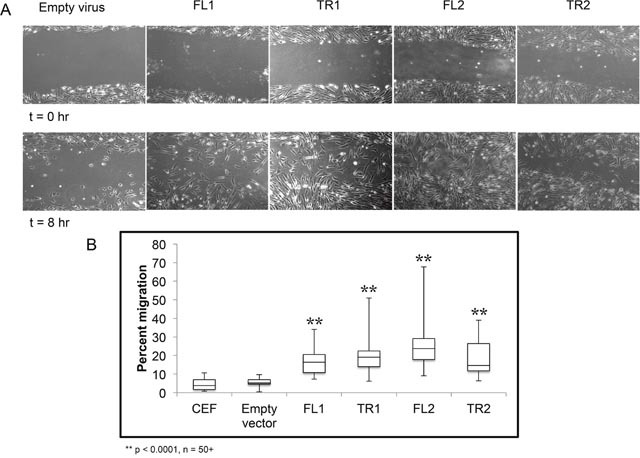

CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 expression induces cell migration in vitro

Due to the enrichment of genes involved in migration, such as MMP9, we next looked at whether cells overexpressing full length or truncated CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 had any differences in ability to migrate. To do this, we made use of a wound healing assay, or scratch assay, in which a confluent plate of CEF cells was scratched to disrupt the monolayer. At subsequent times after inflicting the “wound”, cells were imaged to visualize cell migration (Figure 6A). We observed that cells expressing either full length or a truncated CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 transcript had a significantly higher rate of cell migration compared to an empty vector control.

Figure 6. CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 promote cellular migration in chick embryo fibroblasts.

(A) A scratch assay was performed to monitor cell migration. Representative images of scratches at time 0 and at 8 hours are shown. (B) Quantification of wound closure. On average, uninfected CEF and CEF infected with empty viral vector exhibit approximately 5% wound closure after 8 hours. Cells expressing truncated CTDSPL2 (TR2) exhibited significantly faster cellular migration rates with 18% wound closure on average after 8 hours (p < 0.0001). Cells expressing full length CTDSPL2 (FL2) had the fastest migration with 25% wound closure at the final time point (p < 0.0001). Cells overexpressing CTDSPL truncated and full-length (TR1, FL1) transcripts had intermediate phenotypes with approximately 15-20% migration.

Cells migrating into the wound were quantified, and percent wound closure was calculated (Figure 6B). CTDSPL2 full-length overexpression had the largest effect with 25% wound closure compared to just 5% closure seen in the empty vector control (p < 0.0001). The truncated form of CTDSPL2 had a more modest effect with 18% closure observed on average (p < 0.0001; Figure 6B). Cells expressing CTDSPL truncated and full-length transcripts had intermediate migration rates.

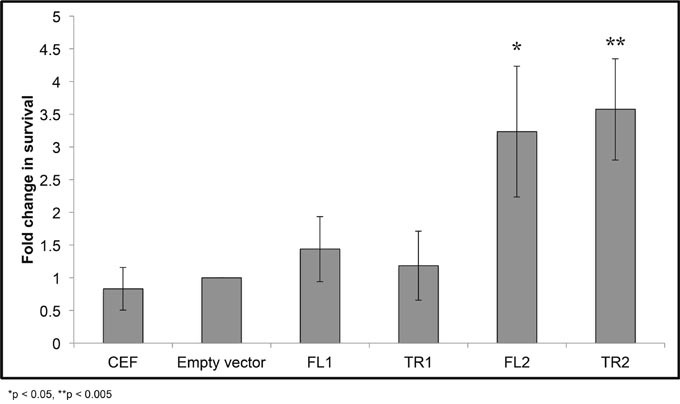

CTDSPL2 overexpression prevents apoptosis induced by oxidative stress

Promotion of cell migration by CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 overexpression was observed when either truncated or full-length transcripts were expressed. Thus, this function does not explain why viral integrations that induce truncations were selected for in the tumors that we analyzed. Integrations in genes may also be selected for because they promote survival. To determine if integrations in CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 are affecting survival, we induced apoptosis in cells expressing either full length or truncated CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 by hydrogen peroxide treatment and measured cell death. Interestingly after 48 hours, cells expressing truncated or full length CTDSPL2 had significantly higher survival rates than cells expressing CTDSPL or empty vector control. CEF cells expressing either form of CTDSPL2 had approximately 3-fold higher survival than cells infected with an empty vector control (Figure 7).

Figure 7. CTDSPL2 protects cells from apoptosis in vitro.

Chick embryo fibroblasts were treated with hydrogen peroxide to induce apoptosis and survival was measured relative to cells infected with an empty viral vector. Expression of either full-length or truncated CTDSPL (FL1, TR1) provided no protection from apoptosis (p < 0.05). Cells expressing either truncated or full length CTDSPL2 (TR2, FL2) showed an approximately 3-fold increase in cell survival (p< 0.05).

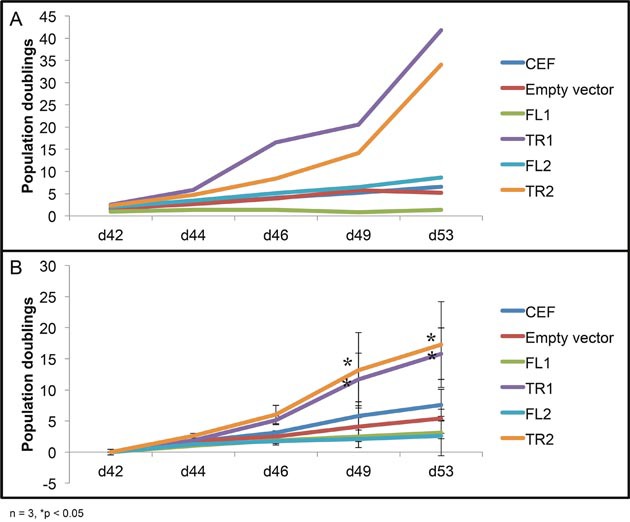

Overexpression of truncated viral fusion CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 transcripts promotes immortalization of primary cells in culture

The typical lifespan of primary chicken embryo fibroblasts in culture is approximately 30 days. After this point, proliferation of CEF cells as well as ALV-infected CEF cells decreases dramatically. Overexpression of either full length CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 did not affect proliferation at later time points. In contrast, cells overexpressing the viral fusion transcripts of CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 did not undergo senescence (Figure 8). These cells continued proliferating at the same rate that was observed at earlier time points (data not shown). This effect of the truncated products on immortalization is likely the reason integrations were selected for in our initial screen of ALV-induced B-cell lymphomas.

Figure 8. Overexpression of truncated CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 promotes immortalization of primary cells in culture.

Proliferation data shown is from day 42 to day 53 after infection. (A) Representative growth curve of CEF cells infected with virus, expressing truncated or full length CTDSPL or CTDSPL2. (B) Average growth curve of three biological replicates. CEF cells as well as cells infected with empty virus stop proliferating at later time points. Cells overexpressing full length CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 (FL1, FL2) proliferate less on average than uninfected CEFs. However, cells overexpressing truncated viral fusion transcripts of either CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 (TR1, TR2) exhibit significantly higher proliferation at later time points indicating that they may be promoting immortalization.

DISCUSSION

In this report we have identified both CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 as common integration sites in ALV-induced B-cell lymphomas. In addition to being common integration sites, a large number of integrations in these genes were clonally expanded, suggesting a role in tumorigenesis. Further evidence for a driving role in cancer is suggested by the presence of identical integrations in primary and secondary tumors within the same bird. This indicates that these integrations were likely an early event in the development of cancer within these birds.

We show that viral integrations in CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 were driving the overexpression of a truncated transcript. Overexpression of CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 caused changes in the expression of genes involved in cellular migration, most notably MMP9, which was upregulated by overexpression of all constructs. Correspondingly, we observed an increase in cellular migration rates in cells overexpressing truncated and full-length transcripts. This, in addition to the observation that integrations in CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 occur in both primary and secondary tumors, suggests a potential role in promoting tumor metastasis. While CTDSPL2 is not well studied, it has been demonstrated to play a role in bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling through dephosphorylation of Smad proteins [24]. This has been shown to strongly promote cell migration in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines [26]. Further, inhibition of BMP signaling suppressed metastasis in mammary cancer [27]. This role of CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 in cellular migration agrees with previously published data that CTDSP1/2/L proteins promote migration through the activation of the SNAIL1 protein, a key regulator of migration [17]. The promotion of cellular migration appears to be a gain of function due to overexpression of the CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 transcripts.

The overexpression of truncated viral fusion transcripts of both CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 promotes immortalization of primary cells in culture. This is a feature unique to the truncated transcripts, as overexpression of full-length forms of both genes did not significantly improve proliferation rates at times past the normal lifespan of CEFs. We believe that this role in immortalization is likely the reason that integrations promoting the expression of truncated forms of both genes are selected for in ALV-induced B-cell lymphomas. This role in immortalization for CTDSPL and CTDPSL2 is interesting to note due to the co-occurrence of CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 integrations with integrations into TERT, which has previously been reported to promote immortalization [28].

CTDSP1/2/L are fairly well characterized genes that have been repeatedly shown to play partially redundant roles. CTDSPL2 seems to be fairly similar to the other members of the CTDSP family in many regards. Some functions are known to overlap, such as regulation of BMP signaling. Here we show that CTDSPL2 promotes metastasis similar to CTDSPL. These overlapping functions, in addition to the observation that despite integrations in both genes, only one is overexpressed in individual tumors, would suggest that CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 might be redundant. However, we observed that expression of CTDSPL2, and not CTDSPL, can protect cells from apoptosis induced by oxidative stress.

CTDSPL2 does have distinct features from the other members of the CTDSP family. For instance, CTDSP1/2/L genes have an intronic microRNA from the miR-26 family. No intronic microRNA has been reported in CTDSPL2. The CTDSPL2 protein, at 53 kDa, is significantly larger in size than CTDSP1/2/L proteins, which all weigh in at around 32 kDa on average. Each protein in the family contains a C-terminal phosphatase domain, but CTDSPL2 has significantly more N-terminal sequence of unknown function. The N-terminal region that is truncated in the viral fusion transcript is predicted to be intrinsically disordered (Figure 4B). Likewise, the truncated portion of CTDSPL is also predicted to be partially disordered. Given that the CTD of RNA polymerase II has been shown to associate with proteins with low-complexity domains, it is possible that these disordered regions are in part responsible for binding of CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 to the CTD. Thus, in the truncated transcript that is expressed in tumors, these proteins may not be able to associate with RNA polymerase II or other substrates.

Furthermore, unlike CTDSP1/2/L proteins, CTDSPL2 has not been previously reported to act on pRb, a main tumor suppressor target common to the other 3 members of the family. However, in our RNA-seq analysis, nearly 75% of the genes that were differentially expressed by 2-fold or more in cells overexpressing CTDSPL2 were E2F target genes. E2F is a transcription factor targeted by pRb. When pRb is dephosphorylated and thus active, it binds E2F, keeping it inactive. Once pRb becomes phosphorylated in G1, it releases E2F allowing it to act on downstream effector genes causing the transition from G1 to S phase [30]. CTDSP1/2/L were shown to dephosphorylate and thus activate pRb [19]. Due to regulation of E2F target genes by CTDSPL2, it seems likely that this protein may also act as a phosphatase on pRb.

Our work suggests that CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 play a role in cancer and seem to have pro-oncogenic characteristics (Figure 9). Expression of either of these genes promotes metastasis in cell culture and CTDSPL2 protects cells from apoptosis. Neither of these functions is affected by the viral truncation. We believe that the main reason integrations in CTDSPL and CTDPSL2 were selected for in B-cell lymphomas is due to the role of the truncated transcripts in immortalization. We hypothesize that the gene truncations imposed by the viral integrations in tumors remove a region of the protein that is responsible for interaction with pRb. The truncated proteins would no longer be able to dephosphorylate pRb and would potentially lose their tumor suppressor function. Genes deregulated by expression of the truncated transcript were also enriched in downstream effectors and processes of the pRb pathway, such as E2F and Sp1 target genes [30]. This suggests that the truncated version of the proteins interacts with pRb differently causing a change in expression of downstream effectors of pRb. We hypothesize that the removal of a portion of a predicted intrinsically disordered region may inhibit these proteins from interacting with its normal protein-binding partners. For CTDSPL2, the truncation also removes a nuclear localization signal that may prevent the protein from reaching the nucleus. pRb has been shown to be a dominant effector of cellular senescence with inactivation of pRb delaying onset of cellular senescence [31, 32]. If the truncated CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 proteins can no longer activate pRb through dephosphorylation, then pRb may become phosphorylated and thus inactive, allowing for evasion of senescence as observed in our cell culture system.

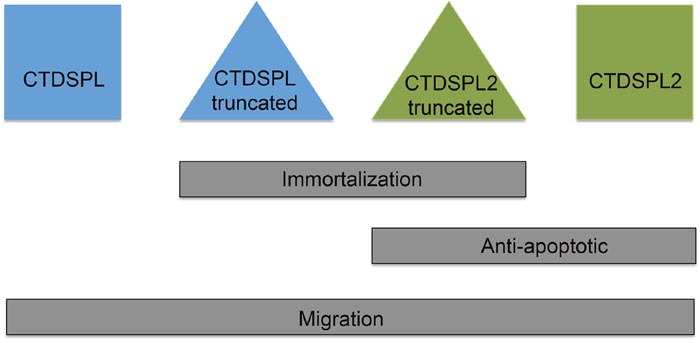

Figure 9. Summary of findings.

Overexpression of the truncated viral fusion transcripts of CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 promote immortalization in primary cell culture. Expression of either full length or truncated CTDSPL2 protected cells from apoptosis. Overexpression of all constructs caused a significant increase in cellular migration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tumor induction

The tumors in this study are rapid onset B-cell lymphomas induced by the subgroup A ALV virus, LR-9, or a variant thereof as described previously [10, 33]. Specifically, tumors in bird A1 and A8 were induced by delta LR-9, a variant with a 42 nt deletion in the gag gene that causes an increased frequency of read-through transcription [34]. Tumors in birds C2 and C3 were induced by an LR-9 variant with a point mutation, G919A. Tumors in birds D2, D3 and D5 were induced by wild type LR-9 virus. Tissue was collected from primary bursal tumors (B) or metastasized liver, kidney, or spleen (L, K, S) tumors.

High throughput sequencing and analysis

Genomic DNA for ALV integration mapping libraries was collected using standard proteinase K digestion followed by phenol-chloroform extraction [6]. Libraries were prepared and analyzed using a custom pipeline as described previously [8]. Integrations were attributed to the nearest RefSeq gene. RNA-Seq libraries were prepared in duplicate using the TruSeq stranded mRNA library kit according to manufacturers directions and sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq platform. Differential gene expression between cells infected with a RCAS(A) viral construct carrying CTDSPL or CTDSPL2 and cells carrying an empty vector control was determined using Cufflinks [35]. Genes with a 2-fold or greater difference in gene expression were considered for further analysis. Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed using g:Profiler and DAVID [36, 37]. GO terms with a p-value of less than 0.05 after Bonferroni correction for multiple testing were considered significantly enriched above background.

Characterization of truncated transcript and protein disorder prediction

RNA was extracted using RNA-Bee reagent (Tel-Test, Inc.). cDNA was prepared using Maxima H reverse transcriptase with an oligo(dT)18 primer (ThermoFisher Scientific). Fusion transcripts were detected by performing PCR with a forward primer in gag immediately before the viral splice donor (TCAAGCATGGAAGCCGTCATAAAG) and a reverse primer within the gene of interest (CTDSPL: TGAAAATGCAGTGCCTGTGC; CTDSPL2: CAGTA AGGTAGTTCGCGGGG).

Protein order was predicted using PONDR (Predictor of Naturally Disordered Regions) VL-XT [38]. Stretches of protein with 10 or more amino acids with a disorder prediction above the threshold 0.5 were considered potential disordered regions.

Quantification of transcript abundance

qPCR to quantify transcript abundance was performed using PowerUp SYBR Green Mastermix (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol on a BioRad C1000 thermocycler / CFX96 Real-Time System. Expression was measured using primers in either CTDSPL (CTACCTGTTGCAGAGTTTATGAAGC, TGAAAATGCAGTGCCTGTGC) or CTDSPL2 (CCCCGCGAACTACCTTACTG, CAGCCTCAACA GCTTGTCCT). A housekeeping gene, GAPDH, was used as an internal reference [6]. qPCR was performed in triplicate and analyzed using the comparative Ct method (ΔΔCt)

Cell culture, plasmid constructs, and viruses

Chicken embryonic fibroblasts (CEFs) were maintained at 39°C, 5% CO2 in 199 media supplemented with 1% chick serum, 1% calf serum, and 2% tryptose phosphate. Overexpression constructs were generated by cloning either full length or a truncated transcript into the RCAS(A) viral expression vector [39]. CTDSPL truncated construct begins at exon 4 (nt 281 from transcription start site in cDNA); CTDSPL2 truncated construct begins at exon 3 (nt 348 from transcription start site in cDNA). Virus was generated via electroporation of constructs into CEFs with subsequent collection of the viral supernatant.

Proliferation and apoptosis assay

Cells were seeded at 0.8 × 106 cells in a 10 cm dish at time 0. To induce apoptosis, cells were treated with 50 μM H2O2 as described [40]. After 48 hours, cells were collected and counted using a BioRad automated cell counter (BioRad TC20) to determine change in cell survival relative to CEFs infected with empty viral vector. Population doublings were calculated from total live cell count at day 2 relative to day 0. Proliferation was then plotted relative to CEFs infected with empty viral vector as a control condition. Significance was assessed using an unpaired t-test.

Scratch assay

A scratch assay was used to detect differences in cell migration as described previously [41]. Briefly, a 100% confluent plate of cells was scratched with a P200 tip at time 0. Closure of the scratch was monitored via light microscopy for 8 hours. Migration of cells into scratch was quantified using ImageJ [42].

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS TABLES

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Neiman and Sandra Bowers, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA for generation of tumors. We thank James Justice for the initial screen of ALV integration sites in ALV-induced B-cell lymphomas. We also thank Yingying Li for generation of CTDSPL and CTDSPL2 viral constructs.

Abbreviations

- CTD

C-terminal domain

- CTDSP

C-terminal domain small phosphatase

- CTDSPL

C-terminal domain phosphatase-like

- CTDSPL2

C-terminal domain phosphatase-like 2

- CTDSP1/2/L

C-terminal domain phosphatase-1, C-terminal domain phosphatase-2 and C-terminal domain phosphatase-like

- TR1

CTDSPL truncated form construct

- FL1

CTDSPL full length construct

- TR2

CTDSPL2 truncated construct

- FL2

CTDSPL2 full length construct

- ALV

avian leukosis virus

- FCP1

(F-cell production 1)

- LTR

long terminal repeat

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- NLS

nuclear localization signal

- CEF

chicken embryonic fibroblast

- Sp1

specificity protein 1

- pRb

retinoblastoma protein

- MMP9

matrix metalloproteinase 9

Footnotes

Author contributions

Conception and design: Shelby Winans and Karen Beemon.

Data acquisition: Shelby Winans, Alyssa Flynn, Sanandan Malhotra, Vidya Balagopal.

Data analysis: Shelby Winans, Sanandan Malhotra.

Writing, review or revision of manuscript: Shelby Winans, Alyssa Flynn, Sanandan Malhotra, Vidya Balagopal, Karen Beemon.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

This work was supported by NIH RO1 CA124596 from the National Cancer Institute to KLB. Shelby Winans was supported in part by Training Grant T32 GM007231.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hayward WS, Neel BG, Astrin SM. Activation of a cellular onc gene by promoter insertion in ALV-induced lymphoid leukosis. Nature. 1981;290:475–80. doi: 10.1038/290475a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Justice J, Beemon KL. Avian retroviral replication. Curr Opin Virol. 2013;3:664–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beemon K, Rosenberg N. Mechanisms of oncogenesis by avian and murine retroviruses. Cancer associated viruses. In: Robinson ES, editor. New York, NY: Springer; 2012. pp. 677–704. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell RS, Beitzel BF, Schroder AR, Shinn P, Chen H, Berry CC, Ecker JR, Bushman FD. Retroviral DNA integration: ASLV, HIV, and MLV show distinct target site pReferences PLoS. Biol. 2004;2:E234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanter MR, Smith RE, Hayward WS. Rapid induction of B-cell lymphomas: insertional activation of c-myb by avian leukosis virus. J Virol. 1988;62:1423–32. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.4.1423-1432.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang F, Xian RR, Li Y, Polony TS, Beemon KL. Telomerase reverse transcriptase expression elevated by avian leukosis virus integration in B cell lymphomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:18952–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709173104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tam W, Ben-Yehuda D, Hayward WS. bic, a novel gene activated by proviral insertions in avian leukosis virus-induced lymphomas, is likely to function through its noncoding RNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1490–502. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Justice J, Malhotra S, Ruano M, Li Y, Zavala G, Lee N, Morgan R, Beemon K. The MET Gene Is a Common Integration Target in Avian Leukosis Virus Subgroup J-Induced Chicken Hemangiomas. J Virol. 2015;89:4712–9. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03225-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilsen TW, Maroney PA, Goodwin RG, Rottman FM, Crittenden LB, Raines MA, Kung HJ. c-erbB activation in ALV-induced erythroblastosis: novel RNA processing and promoter insertion result in expression of an amino-truncated EGF receptor. Cell. 1985;41:719–26. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80052-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Justice JF, Morgan RW, Beemon KL. Common Viral Integration Sites Identified in Avian Leukosis Virus-Induced B-Cell Lymphomas. MBio. 2015;6:e01863–15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01863-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeo M, Lin PS, Dahmus ME, Gill GN. A novel RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain phosphatase that preferentially dephosphorylates serine 5. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26078–85. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301791200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson J, Lepikhova T, Teixido-Travesa N, Whitehead MA, Palvimo JJ, Jänne OA. Small carboxyl-terminal domain phosphatase 2 attenuates androgen-dependent transcription. EMBO J. 2006;25:2757–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeo M, Lee SK, Lee B, Ruiz EC, Pfaff SL, Gill GN. Small CTD phosphatases function in silencing neuronal gene expression. Science. 2005;307:596–600. doi: 10.1126/science.1100801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Visvanathan J, Lee S, Lee B, Lee JW, Lee SK. The microRNA miR-124 antagonizes the anti-neural REST/SCP1 pathway during embryonic CNS development. Genes Dev. 2007;21:744–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.1519107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Knockaert M, Sapkota G, Alarcón C, Massagué J, Brivanlou AH. Unique players in the BMP pathway: small C-terminal domain phosphatases dephosphorylate Smad1 to attenuate BMP signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11940–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605133103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wrighton KH, Willis D, Long J, Liu F, Lin X, Feng XH. Small C-terminal Domain Phosphatases Dephosphorylate the Regulatory Linker Regions of Smad2 and Smad3 to Enhance Transforming Growth Factor-beta Signaling. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38365–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607246200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Y, Evers BM, Zhou BP. Small C-terminal domain phosphatase enhances snail activity through dephosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:640–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806916200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang W, Liao P, Shen M, Chen T, Chen Y, Li Y, Lin X, Ge X, Wang P. SCP1 regulates c-Myc stability and functions through dephosphorylating c-Myc Ser62. Oncogene. 2016;35:491–500. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu Y, Lu Y, Zhang Q, Liu JJ, Li TJ, Yang JR, Zeng C, Zhuang S-M. MicroRNA-26a/b and their host genes cooperate to inhibit the G1/S transition by activating the pRb protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4615–25. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kloet DE, Polderman PE, Eijkelenboom A, Smits LM, van Triest MH, van den Berg MC, Groot Koerkamp MJ, van Leenen D, Lijnzaad P, Holstege FC, Burgering BM. FOXO target gene CTDSP2 regulates cell cycle progression through Ras and p21(Cip1/Waf1) Biochem J. 2015;469:289–98. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kashuba VI, Pavlova TV, Grigorieva EV, Kutsenko A, Yenamandra SP, Li J, Wang F, Protopopov AI, Zabarovska VI, Senchenko V, Haraldson K, Eshchenko T, Kobliakova J, et al. High mutability of the tumor suppressor genes RASSF1 and RBSP3 (CTDSPL) in cancer. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senchenko VN, Anedchenko EA, Kondratieva TT, Krasnov GS, Dmitriev AA, Zabarovska VI, Pavlova TV, Kashuba VI, Lerman MI, Zabarovsky ER. Simultaneous down-regulation of tumor suppressor genes RBSP3/CTDSPL, NPRL2/G21 and RASSF1A in primary non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kashuba VI, Li J, Wang F, Senchenko VN, Protopopov A, Malyukova A, Kutsenko AS, Kadyrova E, Zabarovska VI, Muravenko OV, Zelenin AV, Kisselev LL, Kuzmin I, et al. RBSP3 (HYA22) is a tumor suppressor gene implicated in major epithelial malignancies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4906–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401238101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao Y, Xiao M, Sun B, Zhang Z, Shen T, Duan X, Yu PB, Feng XH, Lin X. C-terminal domain (CTD) small phosphatase-like 2 modulates the canonical bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling and mesenchymal differentiation via Smad dephosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:26441–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.568964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wani S, Sugita A, Ohkuma Y, Hirose Y. Human SCP4 is a chromatin-associated CTD phosphatase and exhibits the dynamic translocation during erythroid differentiation. J Biochem. 2016;160:111–20. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvw018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maegdefrau U, Bosserhoff AK. BMP activated Smad signaling strongly promotes migration and invasion of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Exp Mol Pathol. 2012;92:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owens P, Pickup MW, Novitskiy SV, Giltnane JM, Gorska AE, Hopkins CR, Hong CC, Moses HL. Inhibition of BMP signaling suppresses metastasis in mammary cancer. Oncogene. 2015;34:2437–49. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bodnar AG, Ouellette M, Frolkis M, Holt SE, Chiu CP, Morin GB, Harley CB, Shay JW, Lichtsteiner S, Wright WE. Extension of Life-Span by Introduction of Telomerase into Normal Human Cells. Science. 1998;279:349–52. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sapkota G, Knockaert M, Alarcón C, Montalvo E, Brivanlou AH, Massagué J. Dephosphorylation of the linker regions of Smad1 and Smad2/3 by small C-terminal domain phosphatases has distinct outcomes for bone morphogenetic protein and transforming growth factor-beta pathways. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:40412–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610172200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polager S, Ginsberg D. E2F - at the crossroads of life and death. Trends in Cell Biology. 2008;18:528–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haferkamp S, Tran SL, Becker TM, Scurr LL, Kefford RF, Rizos H. The relative contributions of the p53 and pRb pathways in oncogene-induced melanocyte senescence. Aging (Albany, NY) 2009;1:542–56. doi: 10.18632/aging.100051. http://doi.org/10.18632/aging.100051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: Good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell. 2005;120:513–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polony TS, Bowers SJ, Neiman PE, Beemon KL. Silent point mutation in an avian retrovirus RNA processing element promotes c-myb-associated short-latency lymphomas. J Virol. 2003;77:9378–87. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.17.9378-9387.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O’Sullivan CT, Polony TS, Paca RE, Beemon KL. Rous Sarcoma Virus Negative Regulator of Splicing Selectively Suppresses src mRNA Splicing and Promotes Polyadenylation. Virology. 2002;302:405–12. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:562–78. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reimand J, Kull M, Peterson H, Hansen J, Vilo J. g: Profiler—a web-based toolset for functional profiling of gene lists from large-scale experiments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W193–200. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xue B, Dunbrack RL, Williams RW, Dunker AK, Uversky VN. PONDR-FIT: A meta-predictor of intrinsically disordered amino acids. Biochim Biophys Acta - Proteins Proteomics. 2010;1804:996–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes SH. The RCAS vector system. Folia Biol (Praha) 2004;50:107–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jin DP, Li CY, Yang HJ, Zhang WX, Li CL, Guan WJ, Ma YH. Apoptotic effects of hydrogen peroxide and vitamin C on chicken embryonic fibroblasts: redox state and programmed cell death. Cytotechnology. 2011;63:461–71. doi: 10.1007/s10616-011-9360-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liang CC, Park AY, Guan JL. In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:329–33. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abramoff M, Magalhaes P, Ram S. Image Processing with ImageJ. Biophotonics Int. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.