Abstract

PURPOSE

Primary care physicians spend nearly 2 hours on electronic health record (EHR) tasks per hour of direct patient care. Demand for non–face-to-face care, such as communication through a patient portal and administrative tasks, is increasing and contributing to burnout. The goal of this study was to assess time allocated by primary care physicians within the EHR as indicated by EHR user-event log data, both during clinic hours (defined as 8:00 am to 6:00 pm Monday through Friday) and outside clinic hours.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of 142 family medicine physicians in a single system in southern Wisconsin. All Epic (Epic Systems Corporation) EHR interactions were captured from “event logging” records over a 3-year period for both direct patient care and non–face-to-face activities, and were validated by direct observation. EHR events were assigned to 1 of 15 EHR task categories and allocated to either during or after clinic hours.

RESULTS

Clinicians spent 355 minutes (5.9 hours) of an 11.4-hour workday in the EHR per weekday per 1.0 clinical full-time equivalent: 269 minutes (4.5 hours) during clinic hours and 86 minutes (1.4 hours) after clinic hours. Clerical and administrative tasks including documentation, order entry, billing and coding, and system security accounted for nearly one-half of the total EHR time (157 minutes, 44.2%). Inbox management accounted for another 85 minutes (23.7%).

CONCLUSIONS

Primary care physicians spend more than one-half of their workday, nearly 6 hours, interacting with the EHR during and after clinic hours. EHR event logs can identify areas of EHR-related work that could be delegated, thus reducing workload, improving professional satisfaction, and decreasing burnout. Direct time-motion observations validated EHR-event log data as a reliable source of information regarding clinician time allocation.

Keywords: primary care, health information technology, electronic health records, workload, burnout, practice-based research

INTRODUCTION

Primary care has become increasingly complex,1 with electronic health record (EHR) systems adding to the complexity. Our patients expect same-day access for face-to-face care during clinic hours and rapid responses to telephone calls, patient portal messages, laboratory result inquiries, and prescription renewal requests both during and after clinic hours. This concurrent face-to-face (synchronous) and non–face-to-face (asynchronous) care, combined with administrative and regulatory work (prior authorizations, billing and coding, performance measurement) results in considerable strain on the primary care team. It is imperative to understand factors contributing to workload and identify practical solutions to these challenges.

US physicians spend numerous hours daily interacting with EHR systems, contributing to work–life imbalance, dissatisfaction, high rates of attrition, and a burnout rate exceeding 50%.2–6 Factors such as increased structured documentation requirements, computerized physician order entry (CPOE), inbox management, patient portals, and a redistribution of tasks previously performed by clinical staff to clinicians has led to more work that is not direct face time with patients.7–11 A 2016 study showed physicians from family medicine, internal medicine, cardiology, and orthopedics spent nearly 2 hours in the EHR and on other desk work for every 1 hour of direct patient care.7 In our own primary care system during 2013–2016, despite a stable 2.2 average office visits per panel member per year, telephone calls increased by 3% and MyChart portal encounters increased by 62% to an average of 0.66 per panel member per year. Most primary care physicians have not allocated time for this additional work, and much of the non–face-to-face work occurs on top of already full patient care sessions. To address clinician well-being,12 it is critical to understand how clinician workload is affected by EHR use.

The goal of this study was to assess the time and usage patterns of primary care physicians interacting with the EHR using EHR user-event log data associated with the provision of direct patient care and various asynchronous tasks during and after clinic work hours (defined as 8:00 am to 6:00 pm Monday through Friday).

METHODS

The study was conducted at a large academic health care center consisting of family medicine residency clinics and community-based nonresidency family medicine clinics (community and regional) associated with the University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Family Medicine and Community Health in southern Wisconsin. The Epic EHR system (Epic Systems Corporation) was fully implemented by 2008. We conducted a retrospective cohort study of all nonresident physicians providing care at these sites from July 1, 2013 to June 30, 2016. Because no patient identifiers were included in the analysis, this study was determined to be exempt by the University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board.

We extracted data from our enterprise Epic EHR database. Information about time spent on particular activities was obtained from “event logging,” an automated tracking feature that monitors the accessing and performance of the EHR interface for system administration and security purposes. When a clinician accesses or moves between modules in the EHR interface, such as moving from Progress Notes to Order Entry, a record of these activities is developed, including the time the event occurred, the process activating the event, and other associated information such as user ID and computer location. These tracking features reflect all interactions within the EHR system and can be used by health systems in audits that, for example, identify inappropriate access to certain patient records. Event logging occurs for face-to-face encounters (eg, patients seen in office visits) and non–face-to-face activities (eg, electronic communication with patients, billing and coding, and order entry).

There are more than 1,000 event descriptions to identify user interactions with Epic, including both patient care–related events and system-level technical events. We assigned each EHR event captured by the system event log database to 1 of 15 categories (Table 1) created by consensus among 2 practicing family medicine physicians and a data analyst (B.G.A., J.W.B., W-J.T.), all of whom have expertise in EHR data analytics.

Table 1.

Classifying User-Event Log Data Into 15 EHR Task Categories

| EHR Task Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Clerical | |

| Administrative | Accessing patient demographics for telephone number before calling patient |

| Billing and Coding | Assigning CPT and ICD-10 codes to encounter diagnosis/diagnoses |

| Documentation | Typing into a progress note within any encounter type |

| Order Entry | Placing an order for a medication, laboratory test, consultation or referral, durable medical equipment, others |

| System Security | Logging in, logging out, secondary login to review psychiatric records |

| Medical care | |

| Chart Review-Imaging | Reviewing findings of a chest radiograph |

| Chart Review-Laboratories | Reviewing cholesterol test results |

| Chart Review-Medications | Reviewing medication list |

| Chart Review-Notes | Reviewing an encounter note from office visit, urgent care, emergency department |

| EBM, Point of Care | Accessing an evidence-based resource available through an EHR link, such as UpToDate |

| Problem List | Reviewing or editing the active problem list |

| Inbox | |

| Refills and Results Management | Refilling medications; interpreting new laboratory and imaging results |

| Letter Generation | Developing a letter to patient |

| MyChart Portal | Responding to a patient’s question about a medication through asynchronous e-mail–type dialog |

| Telephone Call | Addressing an incoming telephone call or generating an outgoing telephone call encounter |

CPT= Current Procedural Terminology; EBM = evidence-based medicine; EHR = electronic health record; ICD-10 = International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision.

Validation Procedures

To validate EHR measures of primary care physicians’ time spent on synchronous and asynchronous activities, we completed a time and motion study through direct observation of 14 nonresident family medicine physicians during clinical sessions in residency clinic– and community clinic–based settings over a period of 6 weeks in May and June 2016. Physician volunteers were selected based on sex (6 male, 8 female), years of postresidency experience (<1 to >15 years), clinical full-time equivalents (FTEs) (3 to 9 half days of patient care per week), clinical setting (residency and community), and self-reported experience with EHR use (2–4 to >12 years).

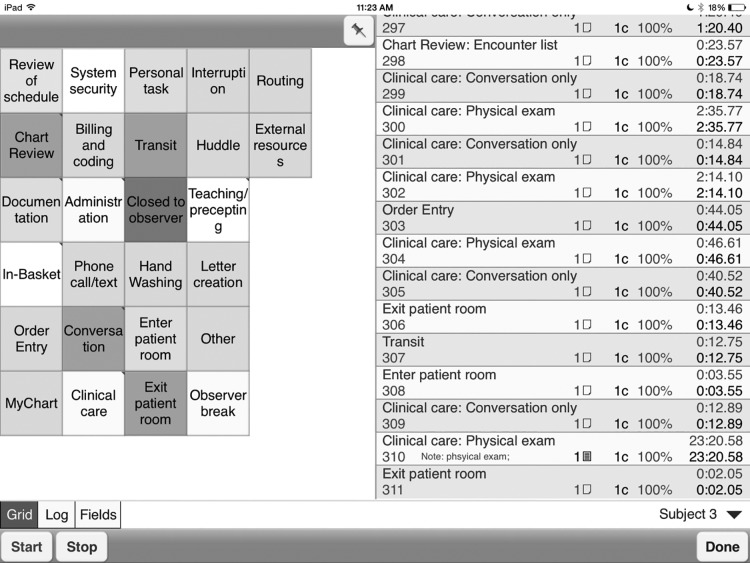

A trained medical student completed 63 hours of direct observation on weekdays from 7:00 am to 7:00 pm. Observations began when clinicians arrived at the clinic and continued through the end of patient care sessions. The student also observed work subsequent to patient care sessions, including completion of documentation, orders, and inbox tasks from the current or earlier patient care sessions. Observations concluded at transitions to the next major activity for the day, such as leaving the clinic or attending a meeting. The WorkStudy+ application (Quetech Ltd) was used on an iPad (Apple Inc) to track clinical activities throughout sessions (Figure 1). In addition to capturing EHR work task categories, direct observations included additional non-EHR activities. Duration of pauses or interruptions while performing tasks was also recorded. Sixty percent of the physician time observed in the clinic related to non-EHR tasks, while 40% was associated with EHR tasks.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of WorkStudy+ application for the iPad.

Note: For direct observation, we developed 15 electronic health record (EHR) task categories plus several non-EHR task categories (eg, staff interactions, e-mail, paperwork and other administrative work, and personal time). Some of the categories shown have further subcategories that appear once the category is selected.

Data Cleaning

Data from the WorkStudy+ application were extracted for processing and analysis. The category assigned to each event in the system event logs, along with the time spent on each event, was compared with the direct observation category assigned by the observer along with the observed time spent on each event. Eleven (5.9%) of the event log category assignments were misclassified based on the direct observation data. These billing and coding tasks were inappropriately assigned to order entry in the original EHR system event log classification and were reassigned to billing and coding for final analysis.

RESULTS

EHR System Event Log Data

We extracted EHR system event logs for 142 family medicine physicians (Table 2). More than 118 million individual EHR system event log record events were created in the 3-year analysis. From more than 1,000 event types trackable in the event log database, our family medicine physicians’ EHR activities created data in 186 event log record event types.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Family Medicine Physicians

| Characteristic | Physicians, No. (%) (N=142) |

|---|---|

| Clinic type | |

| Community | 76 (53.5) |

| Residency | 44 (31.0) |

| Regional | 22 (15.5) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 80 (56.3) |

| Male | 62 (43.7) |

| Years of practice | |

| ≤9 | 33 (23.2) |

| 10–19 | 47 (33.2) |

| 20–29 | 31 (21.8) |

| ≥30 | 31 (21.8) |

| Clinical FTEs | |

| 0.90–1.00 | 40 (28.2) |

| 0.75–0.89 | 22 (15.5) |

| 0.50–0.74 | 33 (23.2) |

| <0.50 | 47 (33.1) |

FTE=full-time equivalent.

Time Spent on Various Tasks

The time physicians spent working with the EHR differed across tasks (Table 3), with some tasks exclusively associated with direct patient care in the clinic (eg, billing and coding), and others associated with both direct patient care and asynchronous tasks (eg, documentation, chart review, and order entry). Work hours were normalized to 1.0 clinical FTE for clinicians who had a clinical FTE of less than 0.9 to 1.0 (71.8%).

Table 3.

Average Time Spent Per Day by EHR Task Category, Comparing Work Hours and After Hours

| EHR Task Category | Time Spent per Day, min | Total Time Spent per Day, min (% of Daily Total) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Work Hours | After Hours | Ratio | ||

| Clerical | ||||

| Documentation | 64 | 20 | 3.2 | 84 (23.7) |

| Order Entry | 35 | 8 | 4.4 | 43 (12.1) |

| Billing and Coding | 10 | 4 | 2.5 | 14 (3.9) |

| System Security | 8 | 2 | 4.0 | 10 (2.8) |

| Administrative | 4 | 2 | 2.0 | 6 (1.7) |

| Subtotal | 121 | 36 | 3.4 | 157 (44.2) |

| Medical care | ||||

| Chart Review – Notes | 47 | 13 | 3.6 | 60 (16.9) |

| Chart Review – Medications | 21 | 5 | 4.2 | 26 (7.3) |

| Problem List | 8 | 4 | 2.0 | 12 (3.4) |

| Chart Review – Laboratories | 6 | 3 | 2.0 | 9 (2.5) |

| EBM, Point of Care | 2 | 2 | 10 | 4 (1.1) |

| Chart Review – Imaging | 2 | 1 | 2.0 | 3 (0.8) |

| Subtotal | 86 | 28 | 3.1 | 114 (32.1) |

| Inbox | ||||

| Refills and Results | 41 | 14 | 2.9 | 55 (15.5) |

| Management | ||||

| MyChart Portal | 15 | 5 | 3.0 | 20 (5.6) |

| Telephone Call | 5 | 2 | 2.5 | 7 (2.0) |

| Letter Generation | 1 | 1 | 1.0 | 2 (0.6) |

| Subtotal | 62 | 22 | 2.8 | 84 (23.7) |

| Total | 269 | 86 | 3.1 | 355 (100.0) |

EBM=evidence-based medicine; EHR=electronic health record.

The average total EHR time per weekday for a 1.0 clinical FTE was 355 minutes (5.9 hours), consisting of 269 minutes (4.5 hours) during clinic hours and 86 minutes (1.4 hours) after clinic hours. The calculation of hours after clinic allocates weekend use of the EHR (51 minutes) to the weekdays by taking the total EHR time after 6:00 pm on Fridays through 8:00 am on Mondays and dividing it by 5 days. Physicians spent nearly one-half of their total EHR time per day (157 minutes, 44.2%) doing clerical tasks and an additional 84 minutes per day (23.7%) managing their inbox (Table 3). We confirmed these results by comparing them with direct observation data.

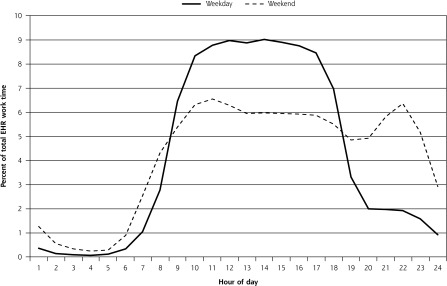

Time physicians spent on EHR activities differed by time of day on weekdays and weekends (Figure 2). Weekday EHR use generally mirrored typical work hours; weekend EHR use peaked around 10:00 am and 10:00 pm.

Figure 2.

Family physicians’ EHR use by time of day.

EHR=electronic health record.

DISCUSSION

This study provides a validated mechanism for EHR task analysis using EHR system event logs to evaluate primary care physician workload. Our event logs indicate that family medicine physicians spend approximately 45% of their workday (4.5 hours) on the EHR. Direct observation data were consistent with this finding. The remaining 55% of the workday (5.5 hours) was spent on non-EHR activities such as direct patient care, team interactions and meetings, paperwork, e-mail, and other work. An additional 1.4 hours per day of EHR time was spent outside of clinic hours (before 8:00 am or after 6:00 pm), including 51 minutes per weekend. This extra time equates to an average workday (excluding time providing care to patients in the hospital) of 11.4 hours, representing a considerable encroachment on physicians’ personal and family lives.

Although others have suggested work task categories for primary care,13 ours is the first taxonomy proposed to capture routine clinical work in EHR systems. This study extends other work by validating EHR audit data with direct observation data within the same clinical environment. These EHR system-event log results are similar to self-report data published by Sinsky et al.7 In that study, 57 physicians from “high-performance” family medicine, internal medicine, cardiology, and orthopedics practices reported 1 to 2 hours of after-clinic work per day tracked in after-hours diaries. Consistency between the direct observation findings, physician self-reported EHR work after hours, and EHR system-event log data supports consideration of user-event log data as an accurate tool for assessing EHR activities associated with both direct patient care and asynchronous work during and after clinic hours.

Our clinicians had more than 20 years in practice and 8 years of experience with our EHR, yet only 40 (28.2%) of the 142 family medicine physicians included in this study had a clinical FTE of 0.9 or 1.0. Forty-four of the 142 physicians worked in residency clinics where their clinical FTE is generally lower because of other responsibilities, but other, nonresidency physicians have chosen to cut back to part time (average of 0.7 clinical FTE) to compensate for their increased workload.

Implications for Primary Care Redesign

It is important to recognize that burnout and the increased workload clinicians have experienced from time spent working in the EHR are due to multiple factors,14 only 1 of which is the EHR system itself. Other factors include inappropriate allocation of EHR tasks to clinicians (eg, submitting a radiograph order that was given verbally in the past); technology-supported guidelines that have placed hard stops in clinical workflows (eg, a clinician cannot proceed until acknowledging a post–hospital discharge medication reconciliation); the problem-focused care paradigm; health care workforce issues; more scrutiny on cost, quality, and patient satisfaction; and rapidly changing regulatory requirements.

Documentation Support

Much of a family medicine physician’s workday (84 minutes) is spent on documentation, so it is imperative to find ways to reduce documentation burden. Although EHR templates have improved documentation efficiency for some, the quality of the clinical note is often lower when compared with that obtained with dictation to transcription. Documentation support staff and additional training in documentation optimization should be readily available for interested clinicians. We have used our EHR system-event logs to identify and offer support to physicians who might benefit from transcription services or voice recognition software (eg, Dragon Medical; Nuance Communications Inc), but few individuals used these documentation support tools regularly during our 6-week observation. It was outside the scope of this study to investigate the use of support tools further, but it should be explored.

Order Entry

Our family medicine physicians spent 44% of their workday (157 minutes) in the EHR doing clerical and other administrative tasks. Computerized physician order entry accounted for 12.1% of their clinic hours (43 minutes) in the EHR. The burden related to order entry has been associated with clinician burnout, dissatisfaction, and intent to leave practice.15 Minimal evidence for increased patient safety related to CPOE16 and reduced order efficiency of this system for physicians compared with other ordering systems implies that alternatives to CPOE should be considered. Having clinical staff enter verbal or handwritten orders (ie, on a standardized paper checklist) from physicians saves time and allows the physician to focus more on the patient.17,18 Some health care systems have implemented conservative policies about providing verbal orders to nonclinician staff limiting this option. The American Medical Association is actively engaged in helping organizations understand and implement guidelines regarding order entry by nonclinician staff.19 Their goal is to support accurate policy interpretation and maximize opportunities in efficiency and satisfaction across health care systems.20

Asynchronous Patient Care

Although virtual visits (ie, patient care delivered by telephone, patient portal, or video calls) are increasing, there is insufficient evidence that such asynchronous care improves health outcomes, cost, and overall health care use.21,22 Further study of the time costs, impact on professional satisfaction, and quality outcomes of asynchronous care is warranted.

Communication

Communication within clinical teams is important. Routing all communication among team members through the EHR adds layers of inefficiency and distracts the team from higher-quality verbal communication. Face-to-face communication is associated with increased efficiency, whereas more electronic communication among team members leads to greater clinician and staff dissatisfaction as well as poorer clinical outcomes and increased health care use among patients with coronary artery disease.23

Study Limitations

Our study had some limitations. Many EHR tasks are associated with multiple subroutines. For example, telephone encounters are often associated with a review of prior notes (Chart Review – Notes) and current medications (Chart Review – Medications) to answer a patient’s question, followed by typing a progress note (Documentation) of the telephone dialog with a patient. As a result, the total time attributed to the Telephone Call category is relatively small given that it captures only the telephone module time and does not account for associated tasks. Future studies could string from beginning to end the multiple tasks that comprise certain encounter types rather than breaking the tasks associated with a bigger event (eg, Telephone Call) into multiple separate tasks (eg, Chart Review – Notes, Chart Review – Medications, and Documentation). This alternate method would give a clearer picture of the total time spent on a given task.

Event logs are created in a server-client request-response environment; there is no way to ascertain what happens on the client side between designated events. It was therefore impossible to distinguish between the time spent when a clinician was active in the EHR and the time spent while having the EHR open but engaging in other activities (eg, performing an examination, talking to a patient or team member), so we applied a cutoff of 90 seconds when no activity was captured by event log records as supported by the pause time observed in our direct observation period.

This study focused on EHR time, not total patient care time, spent by physicians and excludes EHR time associated with inpatient and obstetrics work at other hospitals. As a result, total EHR time would be greater when accounting for this work. Additionally, our regional clinic physicians receive a substantial volume of faxes and other paperwork because regional health system partners may not communicate directly through our EHR. Once that paperwork is transitioned into EHR workflows, total EHR time for those physicians will increase and paperwork burden will decrease.

Our accounting of work outside of clinic hours may be underestimated as many of the physicians had other part-time roles related to education, administration, and research, and would offload EHR work to time allocated to those other obligations between 8:00 am and 6:00 pm on weekdays. For example, a physician may do EHR work resulting from their morning clinic when they were scheduled to prepare a lecture in the afternoon. Our method gives credit to this EHR work as occurring during clinic hours, when it occurred outside of the individual clinician’s clinical FTE work hours.

Conclusions

There are a variety of solutions to address the many facets of physician burnout,15 and developing organizational metrics that are specifically related to decreasing stress from EHR systems is critical.24 In pursuit of finding “joy in practice,”25 stakeholders have proposed 5 solutions to common problems in primary care, including proactive planned care; team-based care that includes expanded rooming protocols, standing orders, and panel management; sharing of clerical tasks including documentation, order entry, and prescription management; verbal communication and shared inbox work; and improved team function. Each solution requires thoughtful EHR system application.

We propose that EHR user-event log data are valid for assessing individual performance within the EHR, influencing workflow redesign, and assessing the impact of organizational changes on task management by health care team members. For example, we discovered that our family medicine physicians were spending nearly as much time on system security (10 minutes) as on reading or editing the problem list (12 minutes) each day. Our organizational leadership subsequently invested in a single sign-in system to reduce clinician time spent on system security. Additionally, we are looking at the time physicians spend on billing and coding since implementation of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision. Our hypothesis is that primary care physicians are spending more time on this task. Eliminating the 14 minutes per day that physicians spend on billing and coding would open up capacity to do other tasks such as inbox management, team huddles, or another 15-minute appointment.

We encourage others to use our proposed EHR task categories to allow comparisons between organizations at the individual and care team levels and by specialty. As there are no information standards for recording user events in EHRs, however, we encourage users of other EHR systems to analyze their own event-log data using these same task categories, compare their findings with ours, and help to determine whether this approach is generalizable. Best practice should be identified from high-performing individuals, teams, and organizations, and used as a goal for other organizations to pursue, but in relationship to clinician and team satisfaction. Organizations could apply this EHR task-analysis framework to measure their effectiveness in supporting their clinicians and care teams in each of the EHR task categories. In addition, organizations could use event-log data to assess their effectiveness of reducing EHR work after clinic hours.

In summary, primary care physicians in our study worked an average of 11.4 hours per weekday, both during and after clinic hours, with nearly 6 hours spent interacting with the computer. Two-thirds of the time on the computer was allocated to clerical and inbox work. EHR event logs can identify areas of EHR-related work that could be delegated, thereby reducing workload, improving professional satisfaction, and reducing burnout. Direct time-motion observations validated EHR event-log data as a reliable source of information regarding clinician time allocation.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

Funding support: Medical student funding for the direct observation validation was provided by the Summer Student Research and Clinical Assistantship (SSRCA) program funds from the University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine and Community Health.

Previous presentation: This study was previously presented in part in a poster, “Work after Work: Evidence From PCP Utilization of an EHR System,” at the North American Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG) Conference, October 24–28, 2015, Cancun, Mexico.

References

- 1.Abbo ED, Zhang Q, Zelder M, Huang ES. The increasing number of clinical items addressed during the time of adult primary care visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(12):2058–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Van Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems and health policy. Rand Corporation; http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR439.html Published 2013. Accessed Mar 27, 2017. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, et al. Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e1):e100–e106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015; 90(12):1600–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman M, Dexter D, Nankivil N. Factors affecting physician satisfaction and Wisconsin Medical Society strategies to drive change. WMJ. 2015;114(4):135–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(11):753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zheng K, Ciemins E, Lanham H, Lindberg C. Examining the Relationship Between Health IT and Ambulatory Care Workflow Redesign. (Prepared by Billings Clinic under contract no. 290-2010-0019I-1). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald CJ, Callaghan FM, Weissman A, Goodwin RM, Mundkur M, Kuhn T. Use of internist’s free time by ambulatory care Electronic Medical Record systems. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11): 1860–1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDonald CJ, McDonald MH. Electronic medical records and preserving primary care physicians’ time: comment on “electronic health record-based messages to primary care providers.” Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(3):285–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy DR, Reis B, Sittig DF, Singh H. Notifications received by primary care practitioners in electronic health records: a taxonomy and time analysis. Am J Med. 2012;125(2):209.e1–209.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holman GT, Beasley JW, Karsh BT, Stone JA, Smith PD, Wetterneck TB. The myth of standardized workflow in primary care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA. 2017;317(9):901–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(7):836–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wolfstadt JI, Gurwitz JH, Field TS, et al. The effect of computerized physician order entry with clinical decision support on the rates of adverse drug events: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23(4):451–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montague E, Asan O. Dynamic modeling of patient and physician eye gaze to understand the effects of electronic health records on doctor-patient communication and attention. Int J Med Inform. 2014;83(3):225–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asan O, Smith P, Montague E. More screen time, less face time - implications for EHR design. J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20(6):896–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Medical Association. Advocacy Update AMA. American Medical Association; https://assets.ama-assn.org/sub/advocacy-update/2016-12-08.html#national Published 2016. Accessed Mar 27, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.AMA STEPSforward American Medical Association’s Practice Improvement Strategies. http://www.stepsforward.org Published 2017. Accessed Mar 27, 2017.

- 21.Goldzweig CL, Orshansky G, Paige NM, et al. Electronic patient portals: evidence on health outcomes, satisfaction, efficiency, and attitudes: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(10):677–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dexter EN, Fields S, Rdesinski RE, Sachdeva B, Yamashita D, Marino M. Patient-provider communication: does electronic messaging reduce incoming telephone calls? J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(5): 613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mundt MP, Gilchrist VJ, Fleming MF, Zakletskaia LI, Tuan W-J, Beasley JW. Effects of primary care team social networks on quality of care and costs for patients with cardiovascular disease. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):139–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Linzer M, Levine R, Meltzer D, Poplau S, Warde C, West CP. 10 bold steps to prevent burnout in general internal medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(1):18–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, Sinsky TA, Margolius D, Bodenheimer T. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(3): 272–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]