Abstract

Objective

Test efficacy of 8-session, 1:1 treatment, Anger Self-Management Training (ASMT), for chronic moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Setting

Three US outpatient treatment facilities.

Participants

90 people with TBI and elevated self-reported anger; 76 significant others (SOs) provided collateral data.

Design

Multi-center randomized controlled trial with 2:1 randomization to ASMT or structurally equivalent comparison treatment, Personal Readjustment and Education (PRE). Primary outcome assessment 1 week post treatment; 8-week follow-up. Primary outcome: Response to treatment defined as ≥1 standard deviation change in self-reported anger. Secondary outcomes: SO-rated anger, emotional and behavioral status, satisfaction with life, timing of treatment response, participant and SO-rated global change and treatment satisfaction.

Main Measures

State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-Revised Trait Anger (TA) and Anger Expression-Out (AX-O) subscales; Brief Anger-Aggression Questionnaire (BAAQ); Likert-type ratings of treatment satisfaction, global changes in anger and well-being.

Results

After treatment, ASMT response rate (68%) exceeded that of PRE (47%) on TA but not AX-O or BAAQ; this finding persisted at 8 week follow-up. No significant between-group differences in SO-reported response rates, emotional/ehavioral status, or life satisfaction. ASMT participants were more satisfied with treatment and rated global change in anger as significantly better; SO ratings of global change in both anger and well-being were superior for ASMT.

Conclusion

Anger self-management training was efficacious and persistent for some aspects of problematic anger. More research is needed to determine optimal dose and essential ingredients of behavioral treatment for anger following TBI.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injuries, anger management, irritability, randomized controlled trials, behavioral treatment

INTRODUCTION

Problematic anger and/or irritability affects many survivors of traumatic brain injury (TBI), with up to one-third reporting new or worse anger since the injury.1–3 These problems occur across the spectrum from mild to severe TBI in both civilian and military samples,4 do not tend to remit spontaneously,5 and are associated with significant limitations in social relationships and resumption of community roles.6,7 The roots of posttraumatic anger are complex and vary across individuals. Pre-injury personality characteristics, direct injury to frontal/executive systems that modulate affect and behavior,8 and cognitive deficits affecting communication and inference in social situations9 may all play a role. In addition, limitations in financial and personal independence and loss of meaningful activity can compound frustration.

Treatment approaches have included pharmacologic agents, among which methylphenidate10 and amantadine hydrochloride11 may be the most promising for people with chronic TBI and irritability; beta-blockers can reduce overt aggression.12 However, there is still insufficient evidence to support a standard pharmacologic approach to anger following TBI, and several commonly used agents may impede cognitive recovery.13

Behavioral approaches include operant conditioning, which have been successful in tightly controlled (e.g., residential) environments.14 Psycho-educational approaches have also been attempted. For example, a small randomized controlled trial15 suggested that people with acquired brain injury (TBI, stroke) could learn principles of anger management that are effective in the general population.16,17 Eight people receiving this one-on-one treatment had greater reduction in self-reported outward expression of anger compared to 8 who were wait-listed. Several uncontrolled studies18,19 have noted positive findings using similar content in a group format.

Based in part on these encouraging findings, we conducted a multi-center randomized controlled trial to test the efficacy of a manualized, one-on-one, psychoeducational treatment protocol called Anger Self-Management Training (ASMT).20 Feasibility and initial evidence of efficacy were examined in a pilot trial, which suggested that the protocol was suitable for people with cognitive limitations due to TBI.21 The ASMT treatment is based on the idea that regardless of the individual contributions of premorbid, organic, and secondary causes, there is a “final common pathway” for the experience and expression of anger linked to 2 deficits in executive function that affect many survivors of TBI: (1) impaired self-awareness, which affects behavioral problems more than cognitive or physical deficits;22,23 and (2) limitations in problem-solving, particularly in social spheres.24 Although many people with anger/irritability due to TBI do apprehend the problem in a general way, they may underestimate its magnitude and consequences, blame others, and produce stereotyped angry reactions to anything perceived as a threat. Self-monitoring has been successfully taught even to people with severe cognitive impairment after TBI,25,26 and teaching the steps of problem-solving has been recommended for executive dysfunction due to TBI based on a systematic review of the literature27. Consequently, we designed the ASMT around 2 types of “active ingredients:” methods of improving self-monitoring and self-awareness of anger, and problem-solving methods that would provide a more flexible repertoire of responses to challenging situations.

We encountered difficult choices in selecting a control or comparison condition for the ASMT trial. A usual care comparison was not feasible because there is no standard treatment for anger and irritability after TBI, and many patients in the chronic phase receive no treatment at all for emotional or behavioral issues.28 We decided against a wait-list control due to the anticipated length of the trial, as well as evidence that wait-listing can bias outcomes in favor of experimental treatments.29 Yet we deemed it important to control for non-specific but beneficial effects of a one-on-one treatment that included an opportunity to ventilate feelings as well as time, attention, and education given by an empathetic professional. We therefore developed a comparison treatment called Personal Readjustment and Education (PRE), which was structurally similar to ASMT in the format, intensity, degree of manualization, provision of outside assignments, and other features described below.

The primary hypothesis was that there would be greater improvement in self-reported anger from pre- to post-treatment in the ASMT condition than in the PRE condition. Specifically,

We predicted that there would be at least 20% greater response rate (defined below) in the ASMT than in the PRE condition, as well as significantly greater decrease in self-reported anger in the ASMT condition.

We also examined the trajectory of treatment response, with the expectation that at least half of participants who responded to ASMT treatment would do so by the 4th session, and that this rate would be at least 10% higher than that in the PRE condition.

We hypothesized that the maintenance in ASMT response rate at 2-month follow-up would exceed that of the maintenance of gains in the PRE condition by at least 10%.

Finally, we examined whether the 2 conditions would have differential effects on reports of participant anger given by relatives or friends (significant others, or SOs), satisfaction with treatment and perception of global change, and secondary outcomes including emotional distress, self- and SO-rated behavioral dysfunction, and satisfaction with life.

METHOD

Overview of design

This study was a 3-center randomized controlled trial comparing 8 sessions of ASMT to 8 sessions of PRE in people with moderate to severe, chronic TBI and problematic anger. After a baseline assessment that included primary and secondary outcome measures and other instruments to characterize the sample, participants were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to ASMT or PRE, respectively, in blocks of 3 within each center. This ratio was selected to provide more data for examining predictors of clinical response and other characteristics of the treatment arm of primary interest. Assessment was done at baseline (T1), after the 4th treatment session (T2), 1 week after the 8th or last treatment session (T3), and 8 weeks after the T3 evaluation (T4) by examiners masked to treatment condition. Primary outcome was measured at T3.

Participants

Details of inclusion and exclusion criteria are reported elsewhere20 and in the Supplemental Digital Content (SDC). In brief, we recruited persons who were known to have TBI and some indication of problematic anger via self-, SO-, or clinician report. Participants had to be aged 18–65, ≥ 6 months post injury, and reporting anger that was new, or worse, since the TBI. They also had to score ≥ 1 standard deviation above the mean for age and gender on the Trait Anger (TA) or Anger Expression-Out (AX-O) subscales of the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2)30, or a score of ≥ 9 on the Brief Anger-Aggression Questionnaire (BAAQ).31 Participants were excluded for major mental illness and involvement in one-on-one psychotherapy.

Significant others

All participants were encouraged to nominate an SO to participate in the trial; however, an SO was not necessary for inclusion. SOs were asked to contribute data concerning the participant at each evaluation (T1 through T4). SOs who were willing and able also participated in 3 of the 8 sessions in the ASMT or PRE treatment.

Measures

TBI-related variables included time post injury, mechanism of injury and severity, as judged by retrospective estimation of post-traumatic amnesia (PTA) duration. This was ascertained using a structured interview that has been used in other studies of chronic TBI, with the retrospective estimate found to correlate reasonably well with PTA measured prospectively.32,33 All participants’ TBI severity was confirmed for study inclusion using prospective medical records; however, not all prospective severity indices (e.g., GCS) were available for all participants. Neuropsychological status was measured at baseline (T1) using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Vocabulary and Matrix Reasoning subtests)34; the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test35 sum of trials 1–5; the Trail Making Test, Part B T-score36; and the error score from the Brixton Spatial Anticipation Test37. Overall functional status was measured with the Glasgow Outcome Scale-Extended.38

The primary outcome, treatment response from T1 to T3, was defined as ≥ 1 standard deviation (SD) change in the direction of improvement on any of the 3 self-report scales used to measure anger at baseline: TA and AX-O from the STAXI-2, and the BAAQ. The TA and AX-O scales are standardized to have SD of 10,30 and the SD of the BAAQ was determined through previous research.31 These 3 scales were chosen because the pilot study of the ASMT suggested variability as to which of them would capture treatment response for individual participants, and the change of 1 SD roughly corresponded to self- and SO-reported change in functional status due to reduction in anger.21 The STAXI-2 is worded at the 6th grade level and has favorable psychometric properties, furnishes age- and gender-corrected T-scores, and is widely used in mainstream anger treatment trials. The 6-item BAAQ is sensitive to more extreme behavioral manifestations of anger, including passive-aggression.31 Secondary outcomes were measured by changes from T1 to T3 and included participant anger measured on all 3 scales from the point of view of the SO; emotional status as measured by the Global Severity Index of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)39, the extent of frontal/executive dysfunction as measured by self- and SO-report on the Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe),40 Total T-score, and satisfaction with life using the Diener Satisfaction With Life Scale.41 Concurrent treatments, including psychoactive medications and doses, were measured at each assessment using a structured interview developed for the study.

To assess the credibility of the PRE condition, both participants and SOs (if participating in treatment) were contacted by Study Coordinators following the first treatment session of either condition and asked to rate 3 items on a Likert-type scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) as to their confidence that the treatment would help the participant; how relevant the treatment seemed for his or her problems; and how much they expected the therapist to help. Responses were added to create expectancy scores ranging from 3 to 15.

Satisfaction with treatment and global assessment of treatment effectiveness was assessed following the 8th session (or the last one attended, if participants dropped out early). For satisfaction with treatment, Coordinators asked 5 Likert-type questions of the participant and SO using the same response scale as above, regarding the degree to which the treatment had helped the participant; how relevant the treatment was for his/her problems; the extent to which the therapist had helped him/her; how well the treatment met his/her personal needs; and the extent to which the treatment would be recommended to others. Scores were summed to create satisfaction scores ranging from 5 to 25. Finally, participants and SOs were asked to rate on a scale from 1 (very much better) to 7 (very much worse) “how (participant’s) anger is now, compared with how it was before you began the study,” and “how this treatment has affected (participant’s) general well-being, compared to before you began the study.” The question about well-being was included to allow for assessment of global non-specific effects of the PRE condition.

Procedures

Study procedures were approved and overseen by Institutional Review Boards at the participating institutions. All participants and SOs provided informed consent. After consent and T1 assessment, participants were randomized using a computer-generated table provided by the study’s Data Coordinating Center, and assigned to the therapist corresponding to their treatment condition. The randomization table revealed only the allocation of the current participant and was used only by the site Study Coordinators, the only personnel aside from the therapists who were unmasked to treatment. The T2 (interim) assessment included all 3 anger measures administered to both participant and SO, as well as the assessment of concurrent medications. The T3 (post treatment) and T4 (8-week follow-up) assessments included all the anger measures plus the measures required to test the secondary hypotheses. T2, T3 and T4 assessments were conducted by phone (or in person if preferred by the participant/SO) by Research Assistants who were masked to treatment condition (see SDC for details on maintenance of masking). Data collectors completed a form at each assessment indicating whether they had been inadvertently unmasked. All assessment instruments were double-scored, i.e., scored independently by the data collector and another person at each site, to minimize errors prior to data entry.

Interventions

Each of the treatment conditions was designed to be completed in 8 weekly sessions of up to 90 minutes each. Participants who deviated in the extreme from this schedule could be terminated from treatment, on the rationale that participants who received the therapy at widely spaced or erratic intervals would not be expected to receive the same benefit as those who participated at the planned therapy intensity (see SDC for details of termination protocol). If an SO was involved in treatment, that person was invited to participate in portions of sessions 1, 4, and 8. The core philosophy, session content, and other aspects of the ASMT and PRE conditions are detailed in Table 1. In brief, the ASMT protocol emphasizes the teaching of behavioral skills (self-monitoring, problem-solving) in addition to focused education about anger and its links to TBI. The PRE protocol provides education about the effects of TBI on personal characteristics, relationships, and community roles. It proscribes advice or guidance from the therapist in favor of empathetic listening, reflection, and encouragement to pursue one’s own posttraumatic readjustment. Both conditions are structured so as to minimize the impact of the cognitive deficits associated with TBI. Additional information about the treatment conditions has been published previously.20,21 All treatment sessions in the current trial were audio recorded. We monitored throughout the trial for adverse events (AE) and serious adverse events (SAE) with the assistance of a Safety Monitor, a psychologist with expertise in the topic who examined unmasked AE and SAE reports to ensure adequate documentation and to alert us to any disproportionate counts in the 2 treatment arms. Further details of risk monitoring are provided in the SDC accompanying this article.

Table 1.

Treatment components of the ASMT and PRE treatment arms.

| Treatment Component | Anger Self-Management Training | Personal Readjustment and Education |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Anger is a normal, adaptive emotion that becomes harder to manage after TBI. Self-management may be strengthened by learning strategies to bolster key executive functions: self-awareness and problem-solving. These skills help P to recognize when anger is triggered, and to choose a reasoned response from an enhanced behavioral repertoire. | People with TBI do not receive adequate education or emotional support, leading to inhibition of natural coping mechanisms. Receiving information, emotional support, and opportunities to ventilate feelings in a warm, permissive atmosphere can help restore P’s ability to cope with problems. |

| Session 1 | Introduction to program content; education about anger (normalization); discussion of specifics of P’s anger responses; introduction of Balance Sheet, listing “reasons” for P’s anger in (-) column and existing Calming Strategies/supports in the (+) column (as techniques are learned throughout program, they are successively added to (+) column). | Introduction to program content; education about TBI and the changes it may lead to; reassurance that recovery may continue over a long period of time. Explanation of “ripple effects” of TBI through 3 circles of life, each of which requires its own adjustment process: the Inner Circle (self, including emotional changes), Middle Circle (relationships with others), and Outer Circle (functioning in the wider community). |

| Session 2 | Education about self-monitoring; reformulation of anger as a cue, not a solution; discussion of P’s characteristic anger cues in body/behavior; introduction of Other Feelings that accompany threats leading to anger, e.g., shame, fear, confusion. | Inner Circle I: Education about cognitive changes: Attention, memory, and executive function. T leads P in exercise to prompt discussion of cognitive changes experienced by P as well as areas that are more intact. |

| Session 3 | Practice in identifying Other Feelings as signals of anger and using them to communicate more effectively (versus communicating with anger). | Inner Circle II: Education about emotional changes and why there may be under- or over-reaction to events. T invites P to ventilate feelings in supportive environment and reinforces value of putting feelings into words. |

| Session 4 | Training and practice in how to read anger signals as a cue to initiate the Time Out technique, a key problem-solving algorithm allowing P to “slow down the action” and formulate a reasoned response. | Middle Circle I: Education about TBI and how it changes family relationships, for better or worse (and sometimes both). Discussion of role changes, guilt, and communication issues, and process of “normal” family adjustments to life changes. |

| Session 5 | Training and practice in use of Mirror Technique, a method of replacing negative with positive communication to defuse anger situations. | Middle Circle II: Friendships, their normal cycle, and how they can be affected by TBI. P completes sociogram analyzing changes in social relationships, including positive ones. |

| Session 6 | Training and practice in Active Listening, a technique to enhance understanding of the viewpoints of others and to avoid non-constructive argument. | Outer Circle I: Discussion of meaning of “community” and how P sees his/her belongingness, participation, and contribution as having changed, and not changed, since TBI. Discussion of changes in roles, if any. |

| Session 7 | Self-assessment and consolidation of skills: P completes self-assessment of progress, evaluates own strengths and weaknesses related to program content, and reviews/practices techniques felt to be most in need of shoring up. | Outer Circle II: P completes self-assessment of progress to date; T prompts discussion of activities out in the community and how these may have been affected by TBI, as well as self-assessment of most fulfilling activities. |

| Session 8 | Review and relapse prevention: Final review of skills and concepts covered in program; discussion of likely pitfalls for future and how they might be handled or circumvented; planning for generalization of learned skills to various situations. | Review of information and topics discussed in program, with emphasis on how P’s situation has not changed (or changed for the better) since TBI and affirmation of ways in which P and SO have been able to adjust and cope with changes. |

| Weekly assignments | Completion of Anger Logs (introduced in Session 1) to record key triggers, bodily/behavioral responses, other key data on incidents occurring between sessions; reviewed at start of Sessions 2–7. | Completion of Personal Events Diary (introduced in Session 1) to record any (not necessarily related to anger) salient events and associated thoughts/feelings between sessions; reviewed at start of Sessions 2–7. |

| Involvement of SO, if any | SO participates in portions of Sessions 1, 4, and 8, and provides brief telephone feedback privately to the T between Sessions 6 and 7, to complete a brief progress assessment parallel to the P’s self-assessment. | SO participates in portions of Sessions 1, 4, and 8, and provides brief telephone feedback privately to the T between Sessions 6 and 7, to complete a brief progress assessment parallel to the P’s self-assessment. |

| Proscribed elements | Topics or concerns not covered in treatment manual; T reminds P that program is focused on anger-related issues and encourages P to seek other help for different issues. | Directive counseling or giving of advice; T must not suggest specific strategies but may encourage P to create and try things on his/her own using his/her own best ways to adjust. |

P= participant; T = therapist; SO= significant other

Reprinted from: Hart T, Brockway JA, Fann JR, Maiuro RD, Vaccaro MS. Anger self-management in chronic traumatic brain injury: Protocol for a psycho-educational treatment with a structurally equivalent control and an evaluation of treatment enactment. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 40:180–192, 2015.

Study therapists were required to have at least 1 year of experience in providing counseling to people with TBI, and a Masters or Doctorate in a relevant clinical discipline. Each site provided 2 therapists, who were randomly assigned to either ASMT or PRE to minimize biases associated with treatment preferences. Therapists in the 2 conditions received separately delivered but equivalent amounts of training, supervision, and feedback based on fidelity assessment (see SDC accompanying this article).

Data analysis

We compared the characteristics of the 2 treatment groups using Chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test (depending on cell sizes) for categorical variables, and Mann-Whitney tests for ordinal or continuous variables. Analysis of primary hypotheses concerning treatment effects were conducted under intent-to-treat assumptions in which participants with missing outcome data were considered non-responders. The rationale for selecting the 20% cutoff as a meaningful between-group difference in response rate is presented in the SDC accompanying this article. We also conducted analyses using only participants who supplied outcome data. We compared response rates overall (primary outcome) and on individual measures of self-reported anger using Chi-squared tests. We used a Fisher’s Exact test to compare the proportions of those responding at T2 in each treatment arm who were classified as responders at T3. The time by treatment interaction in linear mixed effects models, with time considered as categorical for both evaluation of 3 or 4 time points and linear for the three time points T1, T2, and T3, was used for overall summarization of the treatment effect on the scores from the 3 or 4 assessments. In addition to effects of time, treatment group, and their interaction, the models were adjusted for site. Alpha was set at .05 both for the a priori hypotheses and also for secondary analyses, which we considered exploratory in nature.

Effect sizes at T3 and T4 were calculated using a metric recommended for clinical trials that use a binary outcome, the number needed-to-treat (NNT).42 The NNT, the ideal value of which is 1, represents the number of patients that would need to be treated in one condition (in this case, ASMT) to gain 1 more patient responding to the treatment compared to the outcome if the same number were treated in the other condition (PRE). It is calculated as the inverse of the difference between response rates, i.e., 1/([ASMT response rate] – [PRE response rate]).43

RESULTS

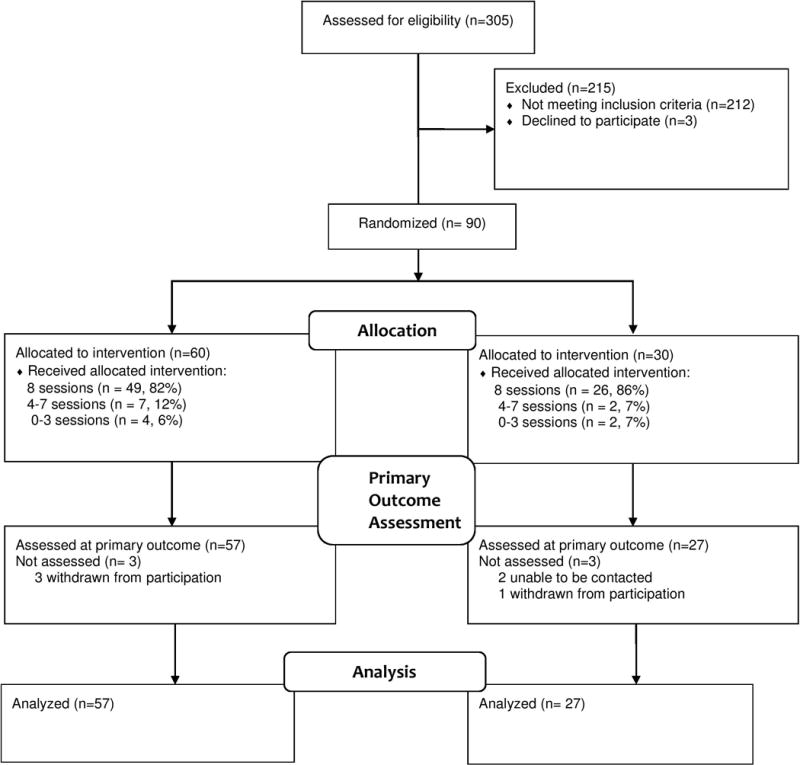

The flow of participants is displayed in Fig. 1. More than 80% of participants in each treatment arm completed all 8 therapy sessions. Treatment conditions were well-balanced on demographic, injury, and neuropsychological variables (Table 2). The typical participant was of average intelligence but worse than average in new learning44 and executive function both by objective measures (Trails B, Brixton) and self-report (FrSBe). Self-reported emotional distress was, on average, elevated to the clinically significant range.39

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram showing flow of participants through trial.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of participants in the two treatment conditions

| PRE (N = 30) |

ASMT (N = 60) |

Sig.1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age: Mean (SD) | 36.2 (13.3) | 30.4 (10.2) | .07 |

| Sex: No. male (%) | 24 (80) | 49 (82) | 1.0 |

| Race/Ethnicity: No. (%) | |||

| White | 22 (73) | 40 (67) | .16 |

| Black | 8 (27) | 13 (22) | |

| Hispanic/Other | 0 (0) | 7 (12) | |

| Education, yrs: Mean (SD) | 13.4 (2.5) | 13.4 (2.1) | .80 |

| Cause of Injury: No. (%) | |||

| Vehicular incident | 17 (57) | 38 (63) | .68 |

| Fall | 6 (20) | 8 (13) | |

| Intentional injury | 5 (17) | 7 (12) | |

| Other | 2 (7) | 7 (12) | |

| Time Post Injury (mo.) | |||

| Median | 72 | 69 | .81 |

| Range | 6 - 339 | 6–298 | |

| PTA Duration, days | |||

| Median | 30 | 30 | .80 |

| <15 | 7 (23%) | 15 (25%) | |

| 15–30 | 9 (30%) | 18 (30%) | |

| 31–90 | 11 (37%) | 15 (25%) | |

| >90 | 3 (10%) | 12 (20%) | |

| GOS-E: Mean (SD) | 5.6 (0.9) | 6.0 (1.0) | .10 |

| Neuropsychological Status: Means/SDs | |||

| RAVLT Sum 5 Trials | 37.8 (9.5) | 40.3 (11.5) | .24 |

| Brixton Error Score | 19.3 (6.7) | 17.2 (7.7) | .17 |

| Trails B T-Score | 40.0 (15.2) | 41.2 (13.0) | .76 |

| FrSBe Total T-Score (self-rating) | 64.4 (17.4) | 62.4 (15.7) | .70 |

| WASI IQ | 94.0 (16.3) | 97.0 (16.1) | .31 |

| BSI Global Severity Index | 66.7 (10.3) | 68.9 (8.0) | .42 |

Statistical significance by Mann-Whitney or Fisher exact as appropriate

There were no significant between-group differences in the proportions of SOs enrolled for participation in treatment and/or data collection. Prior to randomization, 15 (50%) PRE SOs and 38 (63%) ASMT SOs agreed to attend treatment sessions and contribute data. Nine (30%) PRE participants and 14 (23%) ASMT participants lacked an SO to fulfill either role at the time of randomization.

Primary and secondary outcomes

In the analyses described below, there were no significant differences accountable to treatment site. The treatment response data are shown in Table 3. At the primary outcome assessment (T3), the difference in the proportions of responders measured by any of the 3 self-report scales was smaller than hypothesized and not statistically significant, whether cases with missing data at T3 were considered to be non-responders (protocol-specified primary analysis) or if they were omitted from the analysis. However, the difference in response rates for the STAXI-2 TA scale alone was approximately the size hypothesized in favor of the ASMT condition, and was statistically significant. Differences in response rate as reported by the SOs were smaller, with none approaching significance. Interestingly, at T4 (8 weeks post treatment), the self-reported overall response rates had improved in the ASMT condition and deteriorated slightly in the PRE condition. This pattern yielded an overall response difference in favor of ASMT that was about as large as that hypothesized for the primary outcome measured at T3, and which almost reached the nominal level of statistical significance. Regarding clinical effect sizes, at T3 the NNT to achieve a response with ASMT compared to PRE was 11.9; at T4, NNT was only 5.0. There was no significant difference in response rate in either condition, at either T3 or T4, between participants who took psychoactive medications (54% in PRE condition, 55% in ASMT condition) versus those who did not (data not shown).

Table 3.

Response rates overall and for each anger measure included in the primary outcome by self- and SO-report

| Measure | Post-Treatment (T3) Response Rates (%) | Follow-Up (T4) Response Rates (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRE | ASMT | Diff. (95% CI) | Sig.1 | PRE | ASMT | Diff. (95% CI) | Sig.1 | |

| Self-Report, Missing Outcomes treated as Non-Responders (Protocol-specified) | N=30 | N=60 | N=30 | N=60 | ||||

| STAXI-2 Trait Anger | 46.7 | 68.3 | 21.7 (0.3, 41.8) |

.047 | 40.0 | 60.0 | 20.0 (−1.8, 39.8) |

.073 |

| STAXI-2 Anger Expression-Out | 50.0 | 56.7 | 6.7 (−14.6, 27.7) |

.549 | 50.0 | 61.7 | 11.7 (−9.6, 32.5) |

.291 |

| BAAQ | 16.7 | 11.7 | −5.0 (−22.2, 8.4) |

.511 | 13.3 | 11.7 | −1.7 (—)2 |

.820 |

| Overall (response on at least 1 measure) |

63.3 | 71.7 | 8.3 (−11.1, 29.0) |

.421 | 56.7 | 76.7 | 20.0 (−0.1, 40.1) |

.051 |

| Self-Report, Missing Outcomes Removed From Analysis | N=27 | N=57 | N=27 | N=56 | ||||

| STAXI-2 Trait Anger | 51.9 | 71.9 | 20.1 (−1.6, 41.2) |

.031 | 44.4 | 64.3 | 19.8 (−2.8, 40.8) |

.086 |

| STAXI-2 Anger Expression-Out | 55.6 | 59.6 | 4.1 (−17.5, 26.3) |

.483 | 55.6 | 66.1 | 10.5 (−11.0, 32.4) |

.353 |

| BAAQ | 18.5 | 12.3 | −6.2 (−24.8, 8.2) |

.530 | 14.8 | 12.5 | −2.3 (—)2 |

.771 |

| Overall (response on at least 1 measure) |

70.4 | 75.4 | 5.1 (−13.5, 26.3) |

.332 | 63.0 | 82.1 | 19.2 (−0.4, 39.8) |

.056 |

| SO Report | N=16 | N=36 | N=15 | N=31 | ||||

| STAXI-2 Trait Anger | 50.0 | 41.7 | −8.3 (−35.7, 19.6) |

.577 | 46.7 | 45.2 | −1.5 (−30.8, 27.1) |

.923 |

| STAXI-2 Anger Expression Out | 43.8 | 47.2 | 3.5 (−25.0, 30.2) |

.817 | 53.3 | 61.3 | 8.0 (−20.7, 36.8) |

.607 |

| BAAQ | 6.3 | 2.8 | −3.5 (—)2 |

.548 | 0.0 | 0.0 | — | — |

| Overall (response on at least 1 measure) |

62.5 | 63.9 | 1.4 (−24.0, 29.7) |

.924 | 60.0 | 71.0 | 11.0 (--)2 |

.457 |

using Pearson’s chi-square test

Cell sizes too small to permit calculation of confidence interval

The proportions of those who responded to treatment at T3 who had shown a response by the T2 evaluation are shown in Table S-1 (Supplemental Digital Content). In both treatment conditions, over half of those who responded at T3 also showed response at T2, as hypothesized. However, although the difference in this rate favored ASMT by > 10%, which was also hypothesized, the between-group difference did not reach statistical significance.

Table 4 displays the adjusted mean anger scores and the results of the mixed effects model analyses of changes in anger over time. It may be seen that mean values on the anger measures were > 1 standard deviation above normative values at baseline (T1) and were almost identical in the 2 conditions. The analyses of change did not reveal any differential treatment effect on any of the primary measures, although there was a trend toward greater decrease on the STAXI-2 TA scale in the ASMT condition during treatment (T1 through T3), when the effect of time was considered to be linear. Linear mixed effects models for the secondary outcome measures measured at T1, T3, and T4 revealed no significant time by treatment interactions (see Table S-2 in Supplemental Digital Content).

Table 4.

Adjusted mean scores on anger measures at each assessment and time × treatment interaction from mixed effects models

| Measure | Mean Score | Categorical Effect through T3* | Linear Effect* | Categorical Effect through T4* | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRE | ASMT | Diff. | B | CI(B) | Sig. | B | CI(B) | Sig. | B | CI(B) | Sig. | ||

| STAXI-2 Trait Anger | T1 | 63.4 | 64.4 | 1.0 | — | — | .157 | −2.8 | (−5.7, 0.1) | .06 | — | — | .26 |

| T2 | 57.8 | 55.9 | −1.9 | −3.7 | (−9.1, 1.6) | −3.8 | (−9.1, 1.5) | ||||||

| T3 | 53.6 | 49.2 | −4.4 | −5.6 | (−11.4, 0.1) | −5.6 | (−11.3, 0.2) | ||||||

| T4 | 53.7 | 50.2 | −3.5 | −4.9 | (−10.2, 0.4) | ||||||||

| STAXI-2 Anger Expression Out | T1 | 65.7 | 65.1 | −0.6 | — | — | .818 | −0.1 | (−3.4, 3.2) | .95 | — | — | .96 |

| T2 | 56.7 | 57.3 | 0.5 | 1.4 | (−4.7, 7.5) | 1.2 | (−4.9, 7.3) | ||||||

| T3 | 52.5 | 51.9 | −0.7 | −0.3 | (−6.9, 6.4) | −0.3 | (−7.0, 6.4) | ||||||

| T4 | 51.8 | 51.9 | 0.1 | 0.6 | (−6.2, 7.3) | ||||||||

| BAAQ | T1 | 11.8 | 11.2 | −0.5 | — | — | .668 | −0.4 | (−1.4, 0.6) | .46 | — | — | .80 |

| T2 | 9.2 | 8.3 | −0.9 | −0.8 | (−2.7, 1.1) | −0.8 | (−2.7, 1.1) | ||||||

| T3 | 7.8 | 6.6 | −1.2 | −0.8 | (−2.9, 1.3) | −0.8 | (−2.8, 1.3) | ||||||

| T4 | 7.4 | 6.6 | −0.8 | −0.4 | (−2.3, 1.5) | ||||||||

All models adjusted for site

Expectancy of treatment success, treatment satisfaction, and global ratings of change

Table 5 displays the mean scores for the treatment expectancy and satisfaction scales and the global ratings of change in anger and well-being, as well as the proportion of participants and SOs endorsing each of the responses on the latter items. Between-group comparisons of participant ratings revealed significantly higher treatment satisfaction and better global ratings of change in anger for those in the ASMT condition compared to the PRE condition. SOs indicated more expectancy of change in treatment for the ASMT condition, and also rated both anger change and change in well-being significantly better for participants in the ASMT condition compared to those in PRE.

Table 5.

Treatment expectancy, satisfaction, and global changes reported by participants and SOs

| PRE | ASMT | Sig.1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Expectancy (M/SD) | |||

| Participant (n = 86) | 11.9 (2.1) | 12.0 (2.4) | .56 |

| SO (n = 44) | 11.6 (2.1) | 13.0 (1.8) | .04 |

| Treatment Satisfaction | |||

| Participant (n = 78) | 20.4 (3.5) | 22.2 (3.1) | .02 |

| SO (n = 41) | 19.7 (2.9) | 21.3 (3.7) | .08 |

| Global Change in Anger (Participant)2 (n =78) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.4 (1.0) | 1.9 (0.8) | .03 |

| 1 - Very much better | 6 (23%) | 17 (33%) | |

| 2 - Much better | 6 (23%) | 21 (40%) | |

| 3 - A little better | 11 (42%) | 14 (27%) | |

| 4 - No change | 3 (12%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 5 - A little worse | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 6 - Much worse | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 7 - Very much worse | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Global Change in Anger (SO)2 (n = 42) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.3 (1.2) | .01 |

| 1 - Very much better | 0 (0%) | 6 (20%) | |

| 2 - Much better | 3 (25%) | 15 (50%) | |

| 3 - A little better | 7 (58%) | 7 (23%) | |

| 4 - No change | 2 (17%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 5 - A little worse | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | |

| 6 - Much worse | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 7 - Very much worse | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | |

| Global Change in Well-Being (Participant)2 (n = 78) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.2 (0.9) | .15 |

| 1 - Very much better | 5 (19%) | 14 (27%) | |

| 2 - Much better | 6 (23%) | 20 (38%) | |

| 3 - A little better | 13 (50%) | 13 (25%) | |

| 4 - No change | 2 (8%) | 5 (10%) | |

| 5 - A little worse | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 6 - Much worse | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 7 - Very much worse | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Global Change in Well-Being (SO)2 (n = 41) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.8 (0.6) | 2.1 (0.8) | .01 |

| 1 - Very much better | 0 (0%) | 5 (17%) | |

| 2 - Much better | 4 (33%) | 17 (59%) | |

| 3 - A little better | 7 (58%) | 6 (21%) | |

| 4 - No change | 1 (8%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 5 - A little worse | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | |

| 6 - Much worse | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 7 - Very much worse | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Statistical significance by Mann-Whitney tests

Lower scores indicate more favorable change

Other findings, including the results of fidelity assessment, the success of allocation masking, and the incidence of AEs and SAEs, are presented in the SDC accompanying this article.

DISCUSSION

In this investigation we compared ASMT, an anger self-management protocol developed specifically for chronic, moderate/severe TBI, to a structurally equivalent treatment (PRE). The PRE condition was deliberately lacking in the ASMT’s active ingredients, i.e., training in self-awareness of anger and problem-solving methods for anger-provoking situations, but included non-specific ingredients such as education, therapist empathy and attention, and the opportunity to ventilate feelings. The comparison was thus a stringent one, as non-specific ingredients are known to exert powerful influences on emotional and behavioral status,46 and their effects are considered by some to be inseparable from those of theoretically motivated elements in many psycho-educational treatments.29 We therefore expected treatment response in both conditions, but hypothesized a greater response in ASMT compared to PRE. The primary hypothesis was not supported, in that we did not observe a superior response rate within a week of treatment cessation on any of 3 measures of self-reported anger that had shown responsiveness in a pilot trial.21 However, there was a significantly greater post-treatment response rate to ASMT compared to PRE for one measure, the Trait Anger scale from the STAXI-2. These findings underscore the differences among these measures and may provide clues as to the strongest effects of the intervention approaches tested in this trial. Trait anger is described by the STAXI-2 developers as the tendency to perceive a range of situations as annoying, frustrating, or unjust and to respond with anger, whereas outward expression of anger refers to specific behaviors such as nasty or sarcastic remarks, arguing, slamming doors, and other acts of verbal or physical aggression.30 It is plausible that the psychoeducational emphasis of the ASMT protocol, especially in the first sessions which focus on greater awareness of anger and the “reasons” for one’s anger in a range of situations, could invoke a greater change in the interpretation of situations that can trigger anger, versus the idiosyncratic behaviors used to express it.

The examination of treatment response 8 weeks after the end of treatment revealed a trend for further differentiation of the effects of the 2 treatments. There were more treatment responders at 8 weeks compared to shortly after treatment in the ASMT condition, whereas the opposite pattern was true for the PRE condition. Interestingly, for ASMT participants, the response rate had increased for the Anger Expression-Out scale between 1 and 8 weeks post-treatment. Although this is speculative, it may be the case that outward expressions of anger are akin to habits, which take more time and reflection to change compared to the inward reactions of annoyance or irritation.

The interim treatment response (T2) was included in the trial because the 2 main “active ingredients,” self-awareness and problem-solving, are addressed in that order in roughly the first and second halves of the ASMT manual (see Table 1), and there was anecdotal evidence from the pilot investigation21 that significant changes were noted by participants and SOs around the 4th session of ASMT. In this larger sample, almost three-quarters of those who showed treatment response to ASMT did so at the interim assessment. This finding suggests that a briefer treatment sequence, which would be more practical from a clinical standpoint, might be beneficial for a substantial number of persons with anger related to TBI. However, further study would be needed to determine if a truncated program would indeed be efficacious and also persist beyond treatment, as observed here in the T4 assessment.

Despite the relatively small number of SOs who provided satisfaction and global change ratings following treatment, the findings in this area were encouraging. The ASMT SOs rated participants as having significantly more improved anger and emotional well-being overall, compared to PRE SOs (see Table 5). Indeed, 70% of ASMT SOs rated participant anger as “much” or “very much” better after treatment, compared to only 25% of PRE SOs. For their part, the ASMT participants were significantly more satisfied with treatment and rated their anger as significantly more improved compared to their PRE counterparts, although self-ratings of improved well-being were similar in the 2 conditions.

The SO ratings noted above stand in contrast to the degree of change noted on the standardized measures of participant anger administered soon after treatment and 8 weeks later. At neither interval did the SO reports show any superiority for ASMT over PRE. Perhaps the discrepancy may be due to the fact that the global rating asked for an immediate comparison to pre-treatment, i.e., perceived change, whereas the standardized scales require a judgment as to absolute levels of anger at a given point in time. The negative findings on the formal SO assessments of participant anger are reminiscent of those of Hammond and colleagues.11 They found that amantadine resulted in somewhat better self-ratings of aggression and irritability compared to placebo, but there was equivalent improvement in the 2 conditions according to observers (SOs). We agree with those researchers that more work should be devoted to disentangling specific from non-specific effects of interventions tested in clinical trials. For behavioral trials such as the one reported here, this will be especially challenging since non-specific elements such as therapist empathy and the ability to engage the patient in treatment are undoubtedly partly responsible for the uptake of specific “active ingredients.”47

Although effects of the ASMT were not as strong as expected against a structurally equivalent control, the findings of this study are encouraging in several respects. The fact that more than 80% of participants completed all 8 sessions is supportive of the feasibility of the program. The concepts and techniques taught in the ASMT appeared to be understandable and usable by participants with chronic anger and irritability and significant cognitive impairments. However, it should be kept in mind that all participants resided in the community and were excluded for serious limitations in communication. Thus, it cannot be assumed that the concepts and techniques taught in the ASMT would be accessible to those with very severe cognitive or communication deficits. Nor would our results necessarily generalize to people with TBI who deny anger problems that are apparent to others, as all participants had to self-report problems with anger in order to enter the trial. In further investigations we will examine the neuropsychological variables and other factors that predict response to this treatment approach, and use qualitative information obtained at follow-up to assess the most durable features of the ASMT program. Future research should continue to examine the characteristics of the various scales that measure anger and aggression, particularly with respect to persons with TBI-related anger, and should determine the optimal combination of treatment modalities to prevent and ameliorate this important clinical problem.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research, National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, National Institutes of Health, #R01HD061400. We thank Sureyya S. Dikmen, PhD, for guidance and leadership in developing the protocol and Thomas A. Novack, PhD for his assistance with both protocol development and safety monitoring during the trial. Lenore Hawley, MSW, Donald Gerber, PsyD, Gillian Murray, MSW, Claire McGrath, PhD, Josh Dyer, PhD, and Kevin Alschuler, PhD, provided excellent service as study therapists. We also thank Kelly Bognar, Lauren McLaughlin, Cynthia Braden, MA, CCC-SLP, Jennifer Coker, MPH, Christina Baker-Sparr, MS, Christopher Cusick, MA, and Joanie Machamer, MA for their contributions to study coordination, recruitment, data collection, and data management.

Study Funding: National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research of the National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, NIH, #R01HD061400

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

SUPPLEMENTAL DIGITAL CONTENT: Supplemental Digital Content 2-3-17 revision.docx

Contributor Information

Tessa Hart, Institute Scientist, Moss Rehabilitation Research Institute, 50 Township Line Rd., Elkins Park, PA 19027.

Jo Ann Brockway, Clinical Professor Emeritus, Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Roland D. Maiuro, Associate Professor (retired), Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA.

Monica Vaccaro, Research Associate, Moss Rehabilitation Research Institute, Elkins Park, PA.

Jesse R. Fann, Professor, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

David Mellick, IT Project Manager for Research, Craig Hospital, Englewood, CO.

Cindy Harrison-Felix, Director of Research, Craig Hospital, Englewood, CO.

Jason Barber, Research Consultant, Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Nancy Temkin, Professor, Departments of Neurological Surgery and Biostatistics, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

References

- 1.Deb S, Lyons I, Koutzoukis C, Ali I, McCarthy G. Rate of psychiatric illness 1 year after traumatic brain injury. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(3):374–378. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.3.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim S, Manes F, Kosier T, Baruah S, Robinson R. Irritability following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1999;187(6):327–335. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199906000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Zomeren AH, van den Burg W. Residual complaints of patients two years after severe head injury. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1985;48(1):21–28. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.48.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bailie JM, Cole WR, Ivins B, et al. The experience, expression, and control of anger following traumatic brain injury in a military sample. The Journal of head trauma rehabilitation. 2015;30(1):12–20. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanks RA, Temkin N, Machamer J, Dikmen SS. Emotional and behavioral adjustment after traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1999;80(9):991–997. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delmonico RL, Hanley-Peterson P, Englander J. Group psychotherapy for persons with traumatic brain injury: Management of frustration and substance abuse. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 1998;13(6):10–22. doi: 10.1097/00001199-199812000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim E, Lauterbach EC, Reeve A, et al. Neuropsychiatric complications of traumatic brain injury: A critical review of the literature (A report by the ANPA committee on research) Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2007;19(2):106–127. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2007.19.2.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spikman JM, Timmerman ME, Coers A, van der Naalt J. Early Computed Tomography Frontal Abnormalities Predict Long-Term Neurobehavioral Problems But Not Affective Problems after Moderate to Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Journal of neurotrauma. 2016;33(1):22–28. doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neumann D, Malec JF, Hammond FM. The association of negative attributions with irritation and anger after brain injury. Rehabilitation psychology. 2015;60(2):155. doi: 10.1037/rep0000036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wheaton P, Mathias JL, Vink R. Impact of pharmacological treatments on cognitive and behavioral outcome in the postacute stages of adult traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(6):745–757. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318235f4ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammond FM, Sherer M, Malec JF, et al. Amantadine Effect on Perceptions of Irritability after Traumatic Brain Injury: Results of the Amantadine Irritability Multisite Study. Journal of neurotrauma. 2015 doi: 10.1089/neu.2014.3803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleminger S, Greenwood RRJ, Oliver DL. Pharmacological management for agitation and aggression in people with acquired brain injury. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;(3):CD003299. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003299.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silver J, Arciniegas DB. Pharmacotherapy of neurospsychiatric disturbances. In: Zasler ND, Katz DI, Zafonte RD, editors. Brain Injury Medicine: Principles and Practice. New York: Demos; 2007. pp. 963–993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alderman N. Contemporary approaches to the management of irritability and aggression following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2003;13:211–240. doi: 10.1080/09602010244000327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medd J, Tate R. Evaluation of an anger management therapy programme following acquired brain injury: A preliminary study. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2000;10(2):185–201. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deffenbacher JL, Oetting ER, DiGiuseppe RA. Principles of empirically supported interventions applied to anger management. The Counseling Psychologist. 2002;30(2):262–280. [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiGiuseppe R, Tafrate RC. Anger treatment for adults: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10(1):70–84. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aboulafia-Brakha T, Greber Buschbeck C, Rochat L, Annoni JM. Feasibility and initial efficacy of a cognitive-behavioural group programme for managing anger and aggressiveness after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2013;23(2):216–233. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2012.747443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker AJ, Nott MT, Doyle M, Onus M, McCarthy K, Baguley IJ. Effectiveness of a group anger management programme after severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2010;24(3):517–524. doi: 10.3109/02699051003601721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hart T, Brockway JA, Fann JR, Maiuro RD, Vaccaro MJ. Anger self-management in chronic traumatic brain injury: protocol for a psycho-educational treatment with a structurally equivalent control and an evaluation of treatment enactment. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;40:180–192. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hart T, Vaccaro M, Hays C, Maiuro R. Anger self-management training for people with traumatic brain injury: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2012;27:113–122. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e31820e686c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hart T, Sherer M, Whyte J, Polansky M, Novack T. Awareness of behavioral, cognitive and physical deficits in acute traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2004;85:1450–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hart T, Seignourel PJ, Sherer M. A longitudinal study of awareness of deficit after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2009;19(2):161–176. doi: 10.1080/09602010802188393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robertson RH, Knight RG. Evaluation of social problem solving after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2008;18(2):236–250. doi: 10.1080/09602010701734438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dayus B, van den Broek M. Treatment of stable delusional confabulations using self-monitoring training. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2000;10(4):415–427. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schloss P, Thompson C, Gajar A, Schloss C. Influence of self-monitoring on heterosexual conversational behaviors of head trauma youth. Applied Research in Mental Retardation. 1985;6:269–282. doi: 10.1016/0270-3092(85)90001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kennedy MR, Coelho C, Turkstra L, et al. Intervention for executive functions after traumatic brain injury: A systematic review, meta-analysis and clinical recommendations. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation. 2008;18(3):257–299. doi: 10.1080/09602010701748644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bombardier CH, Fann JR, Temkin NR, Esselman PC, Barber J, Dikmen SS. Rates of major depressive disorder and clinical outcomes following traumatic brain injury. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(19):1938–1945. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harrick L, Krefting L, Johnston J, Carlson P, Minnes P. Stability of functional outcomes following transitional living programme participation: 3-year follow-up. Brain Injury. 1994;8(5):439–447. doi: 10.3109/02699059409150995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spielberger C. State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory - Revised. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maiuro R, Vitaliano P, Cahn T. A brief measure for the assessment of anger and aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1987;2(2):166–178. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hart T, Dijkers M, Whyte J, Braden C, Trott C, Fraser R. Vocational interventions and supports following job placement for persons with traumatic brain injury. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 2010;32(3):135–150. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hart T, Benn EK, Bagiella E, et al. Early trajectory of psychiatric symptoms after traumatic brain injury: relationship to patient and injury characteristics. J Neurotrauma. 2014;31(7):610–617. doi: 10.1089/neu.2013.3041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wechsler D. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment Inc.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rey A. L’examen Clinique en Psychologie. Paris: Presses Universitairies de France; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery. Tuscon, AZ: Neuropsychology Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burgess PW, Shallice T. The Hayling and Brixton Tests: Test Manual. Bury St Edmunds, UK: Thames Valley Test Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson J, Pettigrew L, Teasdale G. Structured interviews for the Glasgow Outcome Scale and the Extended Glasgow Outcome Scale: Guidelines for their use. Journal of Neurotrauma. 1998;15(8):573–585. doi: 10.1089/neu.1998.15.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Derogatis L. Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI): Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual. 4. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson Inc.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grace J, Malloy PF. Frontal Systems Behavior Scale (FrSBe): Professional Manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diener ED, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49(1):71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. Bmj. 1995;310(6977):452–454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ. Size of treatment effects and their importance to clinical research and practice. Biological psychiatry. 2006;59(11):990–996. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mitrushina MN, Boone KB, Razani J, D’Elia LF. Handbook of normative data for neuropsychological assessment. 2. NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Milders M, Ietswaart M, Crawford JR, Currie D. Impairments in theory of mind shortly after traumatic brain injury and at 1-year follow-up. Neuropsychology. 2006;20(4):400. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.20.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laska KM, Gurman AS, Wampold BE. Expanding the lens of evidence-based practice in psychotherapy: A common factors perspective. Psychotherapy. 2013 Dec 30; doi: 10.1037/a0034332. 2013: no pagination specified. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paterson C, Dieppe P. Characteristic and incidental (placebo) effects in complex interventions such as acupuncture. British Medical Journal. 2009;330:1202–1205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7501.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.