Abstract

Objective

To describe the implementation of a data-driven, unit-based walkthrough intervention shown to be effective in reducing the risk of workplace violence in hospitals.

Methods

A structured worksite walkthrough was conducted on 21 hospital units. Unit-level workplace violence data were reviewed and a checklist of possible prevention strategies and an Action Plan form guided development of unit-specific intervention. Unit supervisor perceptions of the walkthrough and implemented prevention strategies were reported via questionnaires. Prevention strategies were categorized as either environmental, behavioral or administrative.

Results

A majority of units implemented strategies within 12 months’ post-intervention. Participants found the walkthrough useful, practical, and worthy of continued use.

Conclusions

Structured worksite walkthroughs provide a feasible method for workplace violence reduction in hospitals. Core elements are standardized yet flexible, promoting fidelity and transferability of this intervention.

Keywords: workplace violence, intervention, walkthrough, hospitals, health care worker, workplace safety

Introduction

Workplace violence is an occupational hazard for workers in the United States1 and globally.2 Hospital workers in the U.S. private sector are at increased risk for violence-related injury compared to their counterparts in other industries, with a rate (16.8/10,000 Full-Time Equivalents) quadruple the rate of the private sector overall (4.0/10,000 Full-Time Equivalents).3 These violent events are perpetrated by outsiders to the organization (Type I), patients or patient visitors (Type II), coworkers or supervisors (Type III), and personal relations/domestic partners of the employee (Type IV).4 Forms of workplace violence range from verbal aggression and bullying to physical assault.5

One requirement for hospital accreditation in the U.S. is the development of policies and procedures for the prevention of occupational hazards, including workplace violence.6,7 Standards for prevention of workplace violence should focus not only on physical assault, but also on non-physical behaviors that undermine a culture of safety, such as verbal abuse.7 While several interventions have been tested for the reduction of workplace violence in healthcare settings, none have resulted in long-term reduction of violent events.

This paper describes a randomized-controlled intervention based on documented incidents to reduce patient-to-worker (Type II) workplace violence in hospital settings. Evaluation of this intervention has provided evidence that it is an effective tool for reducing the risks of workplace violence events and related injuries.8 The development, implementation, and fidelity of this intervention are described in this paper.

Previous Interventions

With multiple perpetrators and varied forms of violent events, developing targeted interventions can be difficult. Previous interventions of workplace violence in healthcare settings have generally not included a setting-specific, data-driven design based on analysis of documented incidents, with one exception. Arnetz and Arnetz9 conducted a randomized-controlled intervention in which structured discussions about unit-specific, documented violent incidents were held in conjunction with regularly occurring staff meetings. While it was unit-based and utilized documented incidents, the intervention only provided a structure for discussion of incidents, not prescriptive methods for implementing preventive strategies. Following the intervention, that study reported an increase in documented violent events in the intervention units compared to controls. The authors attributed the increase to enhanced reporting resulting from a heightened awareness of workplace violence and a perception of a non-punitive culture of reporting on intervention units.

Other studies have also included a participatory component in which the researchers met in person with staff or stakeholders.10,11 This allowed for discussion of setting-specific factors contributing to violent events. Gillespie et al.10 developed and implemented an online educational course and in-person training for workplace violence prevention for emergency departments only. They collaborated with a diverse team of stakeholders across the study’s three emergency departments, including employees, managers, and administrators in order to develop course content. While they reported significant decreases in rates of violence for two of three emergency departments post-intervention, comparison sites also experienced a significant decrease. Sites were not randomized, and department-specific data were not used for targeted reduction strategies at each emergency department, but rather a one-size-fits-all approach. Lipscomb et al.11 conducted worksite walkthroughs with unit staff as part of a comprehensive risk assessment for workplace violence at a mental health facility. However, relevant organizational data and documented incidents of workplace violence on the unit were not used to complement the factors identified on-site. Moreover, the study’s intervention and comparison sites were not randomized, and surveys measuring pre- and post-intervention outcomes could not be matched across time by respondent or unit.

Other intervention studies have applied a single method to a limited number of units through programs such as training courses or proactive risk assessments.12,13 For example, Fernandes et al. (2002)12 implemented an educational program for emergency department employees to acquire skills in the prevention of workplace violence. This encompassed a four hour, interactive course with multiple components and teaching strategies. There was a short-term reduction in the number of violent events reported 3 months following the course, but the effect was not sustained, evidenced by a significant increase in the number of violent events at 6 months. Importantly, that study utilized a single site, pre-post design, with no control group. The authors suggested that further research should focus on “objective observation of actual events and a detailed documentation of the nature of the events, the nature of the offenders, and the staff responses”12 (p.53), which is the foundation of the current study. Kling et al.13 implemented a program known as the Alert System,14 which flags patients likely to become aggressive based on a short assessment conducted during their admission. That study focused on Type II (patient-to-worker) violence, and used rates of workplace violence based on patient incident reports and number of hours worked. Incident rates of patient violence decreased during the intervention period, but returned to baseline levels, and even higher for some departments, in the 24 months post-intervention. That study did use comparison groups but was also not randomized.

A review and critique of previous workplace violence interventions, specifically in emergency departments, was conducted by Anderson, FitzGerald, and Luck.15 They classified ten previous interventions into three categories based on their focus: environmental, practices and policies, or skills. Their main critique was the emphasis they found on refining the definition of workplace violence, rather than addressing specific solutions. The primary factors they found lacking, and worthy of more attention, were context-specific strategies, a participatory action research approach, and the use of multi-site samples. The current study applies each of these factors to the foundation of the intervention.

Another study evaluated the change in workplace assault rates across 138 Department of Veterans Affairs healthcare facilities over a six-year period.16 The authors examined the relationship between change in assault rates and implementation of workplace violence prevention strategies classified into three categories: training, workplace practices, and environmental control and security. Overall, there was no significant change in assault rates over time, regardless of prevention strategy implementation. The authors cite three potential reasons for this result. First, there were several facilities that effectively lowered their assault rates after implementing specific prevention strategies, but there were also many that saw an increase in their assault rates; taken together, this may have minimized the individual positive effects when analyzing overall effects across facilities. Second, underreporting is a known issue in the measurement of workplace violence in healthcare.17,18 Third, the authors focused only on rates of assault without consideration of change in assault severity, which may have improved over time. The current study describes an intervention that used unit-specific data, examining rates of both incidence and severity of workplace violence over time,8 and planning data-driven, setting-specific prevention strategies to target relevant factors behind that unit’s violent events.

The intervention described in this paper was the first to apply a standardized framework for violence prevention across a large number of randomized units based on setting-specific data. Results revealed significantly lower risks of patient-to-worker violent events and violence-related injuries on intervention units post-intervention compared to controls.8 The intervention incorporated some of the positive elements of previous interventions (e.g., participatory components, walkthrough methodology), while improving upon prior methods by using a setting-specific, data-driven design based on actual incidents.

Current Study

The current study describes an intervention aimed at reducing workplace violence that was central to a randomized-controlled research project encompassing 41 hospital units across seven hospitals. The intervention incorporated guidelines from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) for the prevention of workplace violence in the healthcare and social assistance industry.6 OSHA recommendations included in the current intervention were participation by stakeholders of management and labor, conducting a hazard risk assessment, employing a walkthrough methodology to identify worksite-specific hazards, and the use of record keeping (i.e. documented incident reports). A structured action plan form and risk factor checklist were also adapted from OSHA,6 and incorporated potential reduction strategies.19

This intervention was designed to be a low cost, practical method for ongoing prevention of workplace violence incidents in healthcare settings. The intervention’s structure comprised core elements that were standardized across work settings. These standardized elements were used to guide individualized strategies within each unit. This was achieved by presenting unit-specific data of workplace violence to each unit, based on recorded incidents, within a standardized format. By maintaining the standardization across units, yet allowing for flexibility of methods within units, this design was intended to promote fidelity and transferability of the intervention.

Intervention fidelity and transferability

Fidelity and transferability are important features of any intervention. Fidelity is the degree to which the intended methods of an intervention were actually followed and implemented.20 There may be several factors within an organization that detract from the fidelity of a well-planned intervention, such as the quality of implementation or willingness to participate.21,22 Transferability is the extent to which an intervention can be feasibly applied to other settings.23 Taken together, the goal is to maintain the fidelity of the intervention’s methods while maximizing its transferability between settings.23 Allowing for flexibility in methods (e.g., adapting tools based on the setting) is one way to promote this goal.23

Cycle of continuous improvement

Development of this intervention was based on principles of the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle.24,25 Using the PDSA cycle, strategies for change are implemented, evaluated, and modified to increase their effectiveness, continuously improving methods over time. This study aimed to provide a starting point for unit supervisors to use the PDSA cycle on their units in order to continuously improve upon workplace violence reduction strategies. The described intervention encompassed the first half of this cycle: unit supervisors and staff planned data-driven strategies (Plan phase) and were accountable for implementing those strategies (Do phase). Ongoing, the intention is for units to improve upon their chosen reduction strategies by continuing to study workplace violence data for their unit (Study phase) and shifting their strategies to target the most salient risk factors for violent events (Act phase). The objective is to make this a participatory process,26 involving both supervisors and staff.

Walkthrough Intervention

The format of the intervention followed a structured worksite walkthrough. This method is suggested by OSHA6 and is considered a critical component of worksite analysis for occupational hazard identification. Walkthrough methodology has been used in previous research on workplace violence as part of a quasi-experimental study,11 but had never previously been implemented using a randomized-controlled design. The advantage of a worksite walkthrough is the engagement of supervisors and staff in the identification and reduction of risk factors for workplace violence within the setting in which the incidents actually occur. Employees are able to point out environmental and other factors that may otherwise not be apparent merely from data analysis of recorded incidents. By combining a walkthrough methodology with a data-driven, randomized-controlled design, the current intervention sought to improve upon previous methodologies.

Materials and Methods

Setting and Participants

The setting for this study was a large metropolitan hospital system in the Midwestern United States comprised of seven hospitals and employing approximately 15,000 workers. Incidents of workplace violence were reported to a central, electronic database housed in Occupational Health Services (OHS) of the hospital system. Participants were supervisors and staff of 21 hospital units across the seven hospitals within this system, randomized to the intervention group.

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Institutional Review Board at Wayne State University and the Research Review Council of the hospital system.

Walkthrough Intervention

Randomization of study units

As part of a larger project, 41 hospital units were identified as being at increased risk for workplace violence using the Hazard Risk Matrix.27,28 This matrix categorized units at risk in terms of probability of workplace violence occurrence and severity of the events recorded. Probability of workplace violence was calculated by examining the incidence rates for each unit over the previous three years. Severity rates for units were calculated using injury data, including costs associated with time away from work and medical treatment over the same time period. Within this matrix, 41 units with the highest probability and/or severity were included in the study as either control or intervention units, assigned at random. Units were randomized using a block design, into six categories (blocks) based on the type of hospital unit: acute care nursing, emergency department, intensive care unit (ICU) nursing, psychiatry, security, and surgery. Twenty-one units were randomized into the intervention group28 and are the subject of the current study.

Data reports

Standardized two-page data reports were developed for each of the 21 intervention units in order to provide a concise summary of the unit’s workplace violence data and to highlight potential targets for intervention. Report content and format was based on hospital stakeholder input and preferences.29 Color graphics were used to create a visual aide while discussing the data with unit supervisors and staff during the walkthrough visit. Reports were based on unit-specific data from four sources:

1. Rates of workplace violence

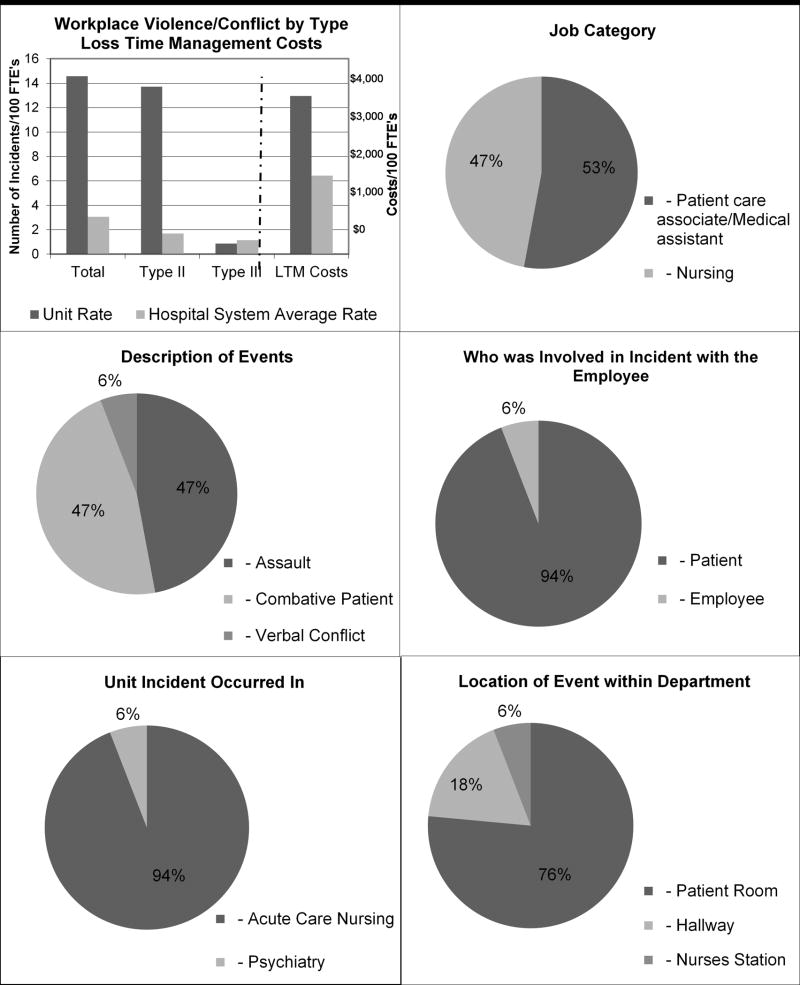

Population-based rates of workplace violence were calculated based on documented incidents over a three-year span from 2010 to 2012. A data analyst in OHS collected documented reports of workplace violence incidents and calculated each unit’s 3-year incidence rates, as well as rates broken down by Types II (patient-to-worker) and III (worker-to-worker). In addition, workplace violence incidence rates were calculated for the entire hospital system. Bar graphs were used to compare unit-level Type II and Type III incidence rates with rates for the entire hospital system.

2. Rates of violence-related injury costs

Population-based rates of violence-related costs were compared in a bar graph between the unit and the hospital system. These were based on data from the Loss Time Management (LTM) department encompassing costs for violence-related injury (e.g., medical treatment cost, paid leave).

3. Descriptive data of violent incidents

Descriptive details of each unit’s incidents of workplace violence were presented in pie diagrams, including the job category of the target, the form of violence (e.g., assault, verbal abuse), the role of the perpetrator (e.g., patient, coworker), and the location of the incident on the unit. The header of the data report also provided the number of incidents and total violence-related cost for the unit for the 3-year period.

4. Pre-intervention questionnaire results

Unit-level results of a pre-intervention employee questionnaire were summarized in bar graphs on the second page of the report. The employee questionnaire was distributed four months pre-intervention to all 41 study units and concerned employee perceptions of the work environment, workplace safety, and experiences of workplace violence.

All of these data were combined into a concise data report that served as a visual aid that was central to the walkthrough meetings with each unit. Figure 1 presents the graphic illustration of rates of violence and violence-related injury costs, and descriptive data of violent incidents developed for a specific intervention unit (questionnaire results are not presented).

Figure 1.

Sample database graphic report.

Walkthrough meetings

Meetings were scheduled with the supervisors of the 21 intervention units within a 6-week period in 2013. These meetings were intended to be as minimally disruptive of the work day and clinical care as possible. They were conducted on the unit, restricted to 45 minutes, and included either the supervisor alone or an additional one to two staff members. Two or three members of the research team and one hospital system stakeholder attended each walkthrough meeting.

Action Plans

An Action Plan form was developed as a standardized tool for selecting and planning violence reduction strategies. This form included a list of suggested prevention strategies adapted from a similar list developed by OSHA.6 Strategies were adapted to the hospital setting by the research team using suggestions from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.19 These strategies were sorted into three categories, meant to guide unit supervisors to consider multiple factors for violence prevention: Environmental (e.g., panic buttons, locks), Administrative (e.g., policies for workplace violence, safety procedures), and Behavioral (e.g., staff knowledge and training for workplace violence incidents). The final list of suggested strategies was refined in a focus group29 by key hospital system stakeholders representing occupational health service, quality and safety, nursing, security, human resources, and labor (Table 1). Following this list of strategies was an Action Plan worksheet for unit supervisors to complete with their staff. Fields included what the unit prevention strategies would be, who would be accountable for carrying them out, and when the strategies would be executed (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Checklist of suggested prevention strategies for workplace violence on hospital units

| ENVIRONMENTAL |

|---|

| ENTRIES/EXITS |

|

| WORK AREA HAZARDS |

|

| WORKPLACE DESIGN |

|

| SECURITY MEASURES |

|

|

|

| ADMINISTRATIVE |

| POLICIES RELATED TO WORKPLACE VIOLENCE |

|

| SAFETY PROCEDURES |

|

| STAFFING |

|

| WORK ROUTINES AND RESOURCES |

|

|

|

| BEHAVIORAL |

| STAFF KNOWLEDGE |

|

| STAFF SKILLS |

|

| STAFF PROFESSIONAL BEHAVIOR |

|

TABLE 2.

Action plan form.

| OTHER STRATEGIES: |

|---|

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| ACTION PLAN: |

| What: |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| Who: |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| When (Time Plan): |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| Contact Person: Email: |

| _________________________________________________________________________________________ |

Walkthrough procedures

A packet that included copies of the data reports, the Action Plan document, and copies of a questionnaire about the walkthrough meeting was presented to each respective unit supervisor. First, the research team described the project’s purpose and methods. Next, the data reports were reviewed and discussed with the unit supervisors and staff, who were asked for their perspectives on the issue of workplace violence and whether they thought the data reports accurately reflected the problem on their unit. When appropriate, supervisors led the research team on a walkthrough of their unit, pointing out specific environmental factors that might contribute to violent events. Researchers took notes at each meeting to record the reactions and contributions of unit supervisors and staff. Following the walkthrough, the Action Plan form was reviewed with the supervisor, who was asked to discuss potential strategies with their staff before completing the worksheet and returning it to the researchers via mail or email within one month. Finally, supervisors and any staff in attendance were asked to complete a questionnaire about the walkthrough meeting.

Walkthrough questionnaire

A paper questionnaire was developed specifically for the intervention to assess the perceptions of the walkthrough meetings. Three items asked about the usefulness, practicality, and the likelihood of continuing to use the methods of the walkthrough intervention, with a rating scale of 1 (not at all) to 10 (very). Participants were also asked whether they thought the walkthrough meeting increased their knowledge of risk factors for workplace violence on their units, and revealed strategies for reducing workplace violence on their unit or at the hospital system, rating ‘yes’ or ‘no.’ An open text box was provided at the end of the questionnaire for any feedback the participants wanted to provide about the walkthrough meeting.

Intervention Follow-Up

In an effort to better evaluate the effects of the intervention, both intervention and control units were surveyed about their actions to reduce workplace violence following the intervention period. An electronic questionnaire was developed to assess whether unit supervisors had implemented any strategies to reduce workplace violence following the intervention. This questionnaire was distributed via email to both intervention and control group supervisors 12 months after the intervention was conducted. Supervisors were asked to describe any strategies implemented over the last 12 months and categorize them as Environmental, Administrative, or Behavioral. Examples of each category were provided, such as those described above in the Action Plan section. If any strategies were implemented, supervisors were asked how their unit benefited from them; if none were implemented, they were asked to explain why. Intervention unit supervisors were provided with a copy of the completed Action Plan that they had previously submitted to the research team and were asked to rate the usefulness of the document on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 10 (very).

Data Analysis

The Action Plans, walkthrough questionnaires, and follow-up questionnaires were descriptively analyzed, examining the scale means and comments provided. Qualitative content analysis was used to examine the common themes of the prevention strategies described on the Action Plan forms. Two researchers independently read through the strategies listed on each form and categorized them as Environmental, Administrative, or Behavioral. Each strategy was assigned one content code based on the type of strategy used (e.g., active shooter training), and codes were aggregated into sub-categories under the three main categories. Any discrepancies in coding and categorization were discussed between the researchers until consensus was reached. A third researcher read the strategies and categories, validating the findings of the first two.

Results

Action Plans

Of the 21 Action Plan forms distributed, 17(81%) were completed and returned. Of those 17, a total of 14 listed specific strategies they planned to implement. Twelve of these specified when these strategies would be executed, and 14 listed a specific person or persons accountable for their implementation. A majority (73.3%) of the supervisors also used the suggested strategy checklists as a tool to mark strategies they had already implemented or were interested in pursuing. Environmental strategies encompassed measures taken to directly improve workers’ physical safety. Behavioral strategies were primarily educational in nature and ranged from de-escalation to active shooter training. Administrative strategies concerned work programs, practices, and policies that were implemented or adapted to better prevent workplace violence. Table 3 gives definitions and examples of main categories and sub-categories that emerged from the prevention strategies provided on the Action Plans.

TABLE 3.

Descriptions of main categories and sub-categories for workplace violence prevention strategies

| Main Category | Sub-Category | Definition/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Strategies | Efforts to improve safety by adaptations to the physical environment/access to security measures | |

| Security presence | Increased security presence/rounding | |

| Physical environment | Hallways/rooms cleared of obstacles; decrease noise level; increase locked storage space for patient and staff belongings | |

| Safety measures | Installation of metal detectors, panic buttons; program hospital telephones for direct dial to security | |

|

| ||

| Behavioral Strategies | Training workers to prevent/mitigate violence and aggressions | |

| Conflict management | Dealing with difficult people; learning to respect co-workers | |

| De-escalation | Dealing with a stressful situation; defensive tactics in assault/combative situations; learning alternative actions | |

| Communication | Debriefing with all staff at time of incident; make staff aware of family violence issues; strategies for communicating with potentially violent patients/visitors | |

| Safety training | Active shooter training; physical management training | |

|

| ||

| Administrative Strategies | Implementation of programs, policies, work practices aimed at increasing worker safety from violence | |

| Safety routines | Detailed check of patient belongings upon admission; enforcement of patient visiting hours/rules; review escape routes; staff to remove self from potential dangerous situation | |

| Safety culture | Incorporate discussions about safety concerns into daily/monthly staff meetings; daily safety huddles; create “safe place” for employees to discuss bullying/conflicts | |

| Policies | Annual net learning on zero tolerance policy; Report incidents, including incidents of conflict between coworkers; tasers/firearms for security | |

| Inter-departmental collaboration | Work with social work for family behavior plan; involve social work and security when potential violent behavior begins | |

Walkthrough Questionnaire

Supervisors and any staff that attended the walkthrough visit were given a questionnaire to complete about the intervention; 32 were returned from 12 units. Respondents overall found the walkthrough useful (M = 7.81, SD = 1.96) and practical (M = 7.84, SD = 2.16) and thought the walkthrough intervention method should be used again (M = 7.62, SD = 1.93). The majority of respondents also reported that the walkthrough increased their knowledge of risk factors for workplace violence on their units (84.4%), and revealed strategies for reducing workplace violence on their unit (65.6%) and at the hospital system (69.8%). Several supervisors commented that they were glad to have the opportunity to address workplace violence reduction on their unit and discuss it with their staff.

“It was helpful speaking to the staff that works on the unit to get their insight about concerns.” [Registered Nurse]

“I felt the team walkthrough was very positive. The team was able to identify potential hazards from an outsider’s point of view.” [Supervisor of Security]

“We are grateful to have the opportunity to shine a light on workplace violence endured by staff on this… unit.” [Supervisor of Acute Care Nursing Unit]

Intervention Follow-Up

One year post-intervention, unit supervisors were asked to complete a follow-up questionnaire about violence reduction strategies they had implemented over the previous 12 months. Sixteen (76.2%) of the intervention units responded. All responding intervention units had implemented at least one violence reduction strategy. In comparison, 10 (50%) control unit supervisors responded to the follow-up questionnaire, with only 8 reporting at least one violence reduction strategy implemented within the previous 12 months.

Intervention unit supervisors rated how useful they thought the Action Plan document was on a scale of 1 to 10, with a mean of 6.08. Most (81.25%) had implemented strategies across multiple categories of factors (Environmental, Administrative, or Behavioral), more so than control unit supervisors (50%). A majority of supervisors described how their efforts to reduce workplace violence on their unit were beneficial.

“I am finding that the staff have been utilizing security and the [de]escalation policy and in turn, families are better behaved and we are able to control the outbursts that used to be common in our area.” [Supervisor of ICU Nursing unit]

Discussion

This study describes a standardized set of methods for data-driven, unit-based workplace violence prevention in hospitals that is largely based on the federal OSHA guidelines for workplace violence prevention. Evaluation of this intervention provided evidence that it was effective against Type II workplace violence incidence and violence-related injuries over time.8 The majority of the 21 intervention unit supervisors returned their Action Plan documents with specific strategies they planned to implement on their unit. Questionnaire responses from supervisors and staff were favorable regarding the methods used for the intervention and most expressed wanting to continue using the walkthrough meetings in the future. The follow-up questionnaire revealed that all responding intervention units had implemented at least one strategy in the year following the walkthrough intervention. Intervention unit supervisors rated the Action Plan form as a moderately useful tool for developing and planning their strategies for violence reduction.

Of note, some control units also implemented their own strategies for violence reduction, without inclusion in the intervention. This was expected, since the hospital units in this study had been identified as being at increased risk for workplace violence,28 and highlights the recognition of workplace violence as a problem by unit supervisors. Contamination of intervention strategies between intervention and control groups may have occurred. Several of the intervention and control units were located within the same hospitals,8 and members of these units may have interacted in hospital-level meetings. However, this would have decreased the likelihood of detecting the significant differences between groups that were previously reported.8 The intervention alone was not the only prompt for supervisors to respond to workplace violence at this hospital system. Rather, the intervention provided a structured methodology to the recognized problem of workplace violence on these high-risk units.

The methods used were intended to incorporate positive elements of previous interventions on workplace violence (e.g., walkthrough methodology)11 and improve upon other elements. Importantly, a standardized framework was achieved through the use of a standardized data report format and based on the principles of continuous quality improvement using the PDSA cycle.24,25 Other improved elements included the use of a setting-specific, data-driven process in order to emphasize relevant problem areas for each unit; a randomized-controlled design; analysis of documented incident reports; and efforts to minimize disruption of worker productivity and clinical care. Visual, graphic comparisons of unit-level rates of violence and violence-related injury costs to the overall hospital system’s rates illustrated the unit’s increased risk for supervisors and staff, underscoring their unit’s need to develop targeted intervention strategies.

Emphasizing a participatory action research approach,26 participation by unit supervisors and staff was a key element of this intervention. Accountability was promoted by involving the individuals who “own the problem” on their respective units. This was intended to increase the likelihood that strategies would be implemented and revised in the long-term on their unit. During the walkthrough meetings, supervisors were able to confirm the data that the research team presented to them. They worked at the unit where these violent events occurred, and recognized the factors that may contribute to the problem. Using a document such as the Action Plan allowed researchers to engage workers in the development of their own strategies and to establish a record for responsibility and follow-up. Importantly, hospital system stakeholders were also engaged in this project, participating in focus group meetings with the research team; in the development and execution of the intervention;29 and in communications with study units throughout.

Fidelity and transferability were supported through the standardization of core elements and flexibility of methods.23 This flexibility was achieved through the adaptation of data reports to the unit level and focus on the development of data-driven, unit-specific strategies for violence reduction. Fidelity was also supported by meeting with hospital system stakeholders22 prior to intervention implementation to discuss the intervention methods and revise the suggested strategies to be more relevant to their organization. The follow-up questionnaire served as a measure of intervention fidelity, as suggested by Dusenbury et al.,20 by asking unit supervisors to review their Action Plan form and detail the strategies they had implemented following the intervention. Transferability was promoted through the feasibility of methods as well.23 Minimum training is required to continue these methods, as the Action Plan form in itself provides a structured foundation for strategy development and planning.

In order to reduce workplace violence, targeted strategies should be developed based on details of the violent events that are relevant to the specific work site.30 Moreover, strategies need to be tailored to the needs and circumstances of individual work units. Workplace violence in hospitals may take many forms (e.g., physical assault, threats) and perpetrators may be patients, patient visitors, or outsiders to the organization. Thus, a one-size-fits-all approach may not be appropriate for the prevention of this occupational hazard.31 However, results of this study suggest that the intervention framework can be standardized, at the same time allowing for strategies to be data-driven yet flexible for each work unit’s experience of workplace violence.

The foundation of an intervention on workplace violence such as this requires a reliable surveillance system that collects data of threats and incidents over time.32–34 The current study used documented incident reports collected over time and stored in a central, electronic database. While other hospitals may not be in position to replicate this exact surveillance system, regular collection of reports of violence is important. Many hospitals lack a systematic reporting system for workplace violence events.35 This lack of a standardized reporting mechanism contributes to underreporting of workplace violence, resulting in a lack of data to guide intervention strategies.29 Establishing a reliable data source is an important first step in the reduction of workplace violence.

Walkthrough meetings

The walkthrough meeting was the crux of the intervention. It served as the point of contact between researchers, hospital stakeholders, and the individuals experiencing workplace violence. The meetings involved bi-directional sharing of information; researchers aggregated data and presented it in a way that highlighted prevalent factors for violence; supervisors and staff confirmed the data and shared their own insights on how violence was perpetrated at their workplace. The data reports succinctly summarized a great deal of data into two pages that were entirely comprised of graphs; this made the information easy to review and discuss. The Action Plan was a valuable tool for integrating the information from both sides and channeling the data into targeted strategies. A representative of hospital management participated in every walkthrough. This served a dual purpose: (1) management’s presence underscored the importance of workplace violence prevention for unit supervisors and staff; and (2) management representatives could learn the procedures, to sustain the walkthrough practice after the conclusion of the research study.26

Scheduling the walkthrough meetings was somewhat challenging given the demanding work schedules of hospital supervisors and staff. It was helpful to have members of the research team who also worked at the hospital system. One of the stakeholder team members was known by many of the supervisors, and aided in communication with units whose supervisors were difficult to contact. There were organizational changes occurring around the time of the study, and this contributed to the challenge of finding a window of time in which to meet. In order to ensure complete participation in the intervention, the research team made early contact via email with the intervention unit supervisors regarding the walkthrough meetings, and follow up communications were made via email and telephone. Reminder emails were also sent to unit supervisors from the hospital system’s Chief Nursing Officer, who was an active stakeholder representative throughout the project.

Limitations

The researchers did not measure the cost of this intervention, which may present one limitation to this study. While the worksite walkthroughs did not incur large costs, there was preparation for the walkthroughs: questionnaire distribution and worksite data analysis. The cost of actual strategy implementation was not assessed either. However, time taken from patient care and productivity was minimized, holding the meeting to less than one hour and including few employees, if any, beyond the supervisor. Going forward, walkthrough meetings can be conducted by one or two hospital system stakeholders as part of their regular site visits. The collection and analysis of incident reports was the most resource-intensive portion, and was performed as part of the regular job duties of data analysts within Occupational Health Services. A helpful follow-up would include assessing costs of resources and finances by the individual units.

A second limitation was the modest number of intervention units that returned the walkthrough questionnaires. The feedback provided on these questionnaires revealed the perceived usefulness and practicality of the intervention methods, and the extent to which supervisors would like to continue the use of those methods for future violence prevention efforts. While some walkthrough meetings allowed for time at the conclusion for supervisors and staff to fill out and return the questionnaires at once, other walkthrough meetings took more time to complete and the questionnaires required a mail-in response. This may have deterred some response, despite reminder emails sent by the researchers.

A third limitation was the moderate response rate from unit supervisors on the follow-up questionnaire. It is possible that non-respondents had not implemented any violence prevention measures and/or were more negative to the intervention than those supervisors who responded. However, those who did respond provided valuable insight into how they made use of the walkthrough intervention and data reports. Healthcare employees work within stringent schedules and often manage the care of multiple patients. Even so, this intervention provided a feasible methodology for maintaining contact with these busy individuals. In the future, it may be useful to identify a point of contact, other than the supervisor, at each intervention unit in order to promote accountability for follow up.

A fourth limitation stemmed from several organizational changes at the hospital system during the study period. These changes affected the availability of some unit supervisors and unease among some hospital employees during upper management transitions. Despite these changes, the study still received positive feedback via surveys and there was full participation by intervention units during the intervention period. This speaks to the feasibility of this methodology within a dynamic organizational environment, which characterizes most hospitals.

Conclusion

This study described the elements and methods of an adaptable, standardized intervention that has been shown effective in reducing the risk of workplace violence in hospitals.8 Using setting-specific data reports and engaging worksite supervisors, staff, and hospital system stakeholders, data-driven strategies can be developed that target the salient risk factors for violent events specific to each work unit. Using a tool such as an Action Plan form allows each unit to develop and implement focused strategies, with deadlines for implementation, reinforcing accountability. These elements were intended to produce a low cost intervention to reduce workplace violence with high fidelity and transferability.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This study was funded by The Centers for Disease Control-National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [CDC-NIOSH], grant number R01 OH009948. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of CDC-NIOSH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no competing interests/conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS] Nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses requiring days away from work 2014. 2015 Available at: http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/osh2.pdf.

- 2.Wiskow C. Joint Programme on Workplace Violence in the Health Sector. Geneva: 2003. Guidelines on workplace violence in the health sector. Available at: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/interpersonal/en/WV_ComparisonGuidelines.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS] Occupational injuries and illnesses and fatal injuries profiles. 2014 Available at: http://www.bls.gov/data/#injuries.

- 4.Injury Prevention Research Center (IPRC) A Report to the Nation. University of Iowa; 2001. Feb, Available at: http://www.publichealth.uiowa.edu/IPRC/resources/workplace-violencereport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson D, Clare J, Mannix J. Who would want to be a nurse? Violence in the workplace - a factor in recruitment and retention. J Nurs Manag. 2002;10:13–20. doi: 10.1046/j.0966-0429.2001.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) Guidelines for preventing workplace violence for health care and social service workers. Washington, DC: 2015. 3148-04R. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3148/osha3148.html. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joint Commission. Sentinel Event Alert, Issue 40: Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. The Joint Commission. 2008 Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_alert_issue_40_behaviors_that_undermine_a_culture_of_safety/ [PubMed]

- 8.Arnetz JE, Hamblin L, Russell J, et al. Preventing patient-to-worker violence in hospitals: outcome of a randomized controlled intervention. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(1):18–27. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnetz JE, Arnetz BB. Implementation and evaluation of a practical intervention programme for dealing with violence towards health care workers. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31(3):668–680. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gillespie GL, Gates DM, Kowalenko T, Bresler S, Succop P. Implementation of a comprehensive intervention to reduce physical assaults and threats in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2014;40(6):586–591. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipscomb J, McPhaul K, Rosen J, et al. Violence prevention in the mental health setting: the New York State experience. Can J Nurs Res. 2006;38(4):96–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandes CMB, Raboud JM, Christenson JM, Bouthillette F, Bullock L, Ouellet L. The effect of an education program on violence in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39(1):47–55. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.121202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kling RN, Yassi A, Smailes E, Lovato CY, Koehoorn M. Evaluation of a violence risk assessment system (the Alert System) for reducing violence in an acute hospital: a before and after study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(5):534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kling R, Corbiere M, Milford R, Morrison JG, Craib K, Yassi A, et al. Use of a violence risk assessment tool in an acute care hospital: effectiveness in identifying violent patients. AAOHN J. 2006;54(11):481–487. doi: 10.1177/216507990605401102. (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson L, FitzGerald M, Luck L. An integrative literature review of interventions to reduce violence against emergency department nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(17–18):2520–2530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohr DC, Warren N, Hodgson MJ, Drummond DJ. Assault rates and implementation of a workplace violence prevention program in the Veterans Health Care. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53(5):511–516. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31820d101e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arnetz JE, Hamblin L, Ager J, et al. Underreporting of workplace violence: comparison of self-report and actual documentation of incidents in hospital settings. Workplace Health Saf. 2015b;51(2):200–210. doi: 10.1177/2165079915574684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peek-Asa C, Schaffer KB, Kraus JF, Howard J. Surveillance of non-fatal workplace assault injuries, using police and employers’ reports. J Occup Environ Med. 1998;40:707–713. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199808000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (CDC/NIOSH) Workplace violence prevention strategies and research needs. 2006 CDC/NIOSH, Cincinnati, Ohio. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2006-144/pdfs/2006-144.pdf.

- 20.Dusenbury L, Brannigan R, Falco M, Hansen WB. A review of research on fidelity of implementation: implications for drug abuse prevention in school settings. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(2):237–256. doi: 10.1093/her/18.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci. 2007;2:40. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasson H. Systematic evaluation of implementation fidelity of complex interventions in health and social care. Implement Sci. 2010;5:67. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kilbourne AM, Neumann MS, Pincus HA, Bauer MS, Stall R. Implementing evidence-based interventions in health care: application of the replicating effective programs framework. Implement Sci. 2007;2:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deming WE. Out of the Crisis, 1986. Cambridge, Mass: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for Advanced Engineering; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor MJ, McNicholas C, Nicolay C, Darzi A, Bell D, Reed JE. Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;23(4):290–298. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lingard L, Albert M, Levinson W. Grounded theory, mixed methods, and action research. BMJ. 2008;337:459–461. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39602.690162.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health [CDC/NIOSH] Focus on prevention: conducting a hazard risk assessment. 2003 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/mining/UserFiles/works/pdfs/2003-139.pdf.

- 28.Arnetz JE, Hamblin L, Ager J, et al. Application and implementation of the hazard risk matrix to identify hospital workplaces at risk for violence. Am J Ind Med. 2014;57:1276–1284. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnetz JE, Hamblin LE, Luborsky M, Essenmacher L, Aranyos D. Using database reports to reduce workplace violence: perceptions of hospital stakeholders. Work. 2015c;51:51–59. doi: 10.3233/WOR-141887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnetz JE, Aranyos D, Ager J, Upfal MJ. Worker-on-worker violence among hospital employees. Int J Occup Env Heal. 2011b;17:328–335. doi: 10.1179/107735211799041797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(17):1661–1669. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1501998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Azaroff LS, Levenstein C, Wegman DH. Occupational injury and illness surveillance: conceptual filters explain underreporting. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(9):1421–1429. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bensley L, Nelson N, Kaufman J, Silverstein B, Kalat J, Shields JW. Injuries due to assaults on psychiatric hospital employees in Washington state. Am J Ind Med. 1997;31:92–99. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0274(199701)31:1<92::aid-ajim14>3.0.co;2-2. (1997) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pransky G, Snyder T, Dembe A, Himmelstein J. Under-reporting of work-related disorders in the workplace: A case study and review of the literature. Ergonomics. 1999;42(1):171–182. doi: 10.1080/001401399185874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnetz JE, Aranyos D, Ager J, Upfal MJ. Development and application of a population-based system for workplace violence surveillance in hospitals. Am J Ind Med. 2011a;54:925–934. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]