Abstract

Objective

To systematically review healthy lifestyle interventions targeted to adolescents and delivered using text messaging (TM).

Data Source

PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and Web of Science databases

Study Inclusion Criteria

Research articles published during 2011–2014; analyses focused on intervention targeting adolescents (10–19 years of age), with healthy lifestyle behaviors as main variables, delivered via mobile-phone-based TM.

Data Extraction

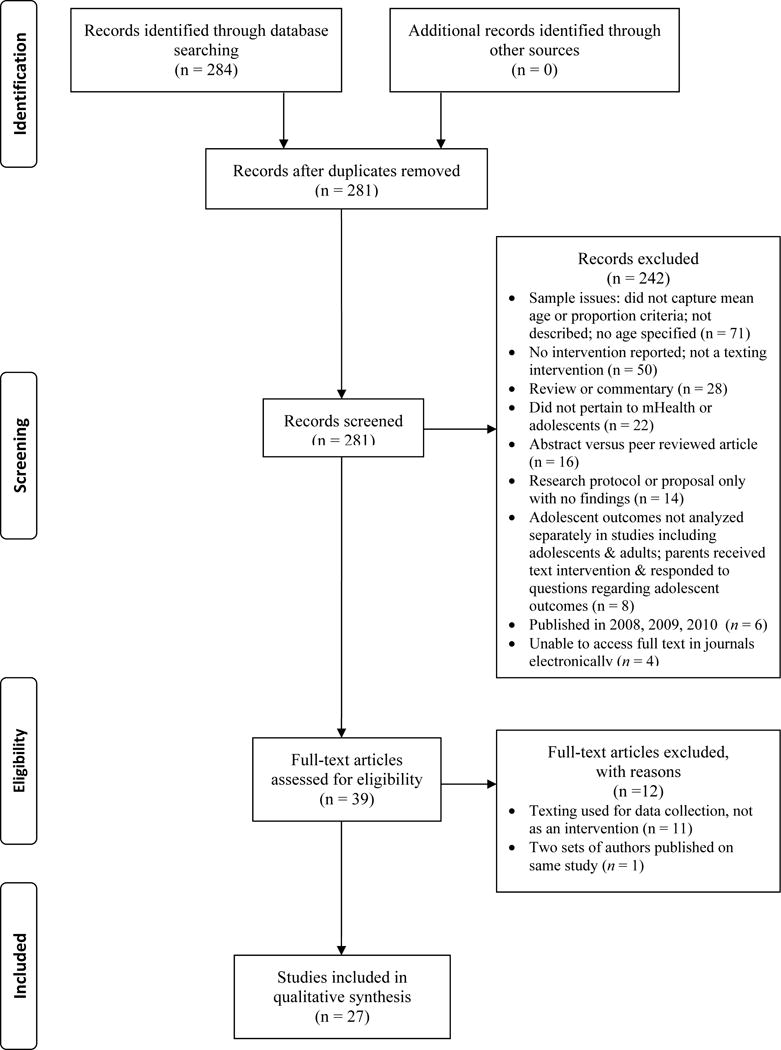

Authors extracted data from 27/281 articles using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) method.

Data Synthesis

Adolescent and setting characteristics, study design and rigor, intervention effectiveness, challenges, risk of bias.

Results

Across studies, 16/27 (59.3%) included non-Caucasians. Gender was split for 22/27 (81.5%) studies. Thirteen studies were randomized controlled trials. There was heterogeneity among targeted conditions, rigor of methods, and intervention effects. Interventions for monitoring/adherence (n = 8) reported more positive results than those for health behavior change (n = 19). Studies that only included message delivered via TM (n = 14) reported more positive effects than studies integrating multiple intervention components. Interventions delivered using TM presented minimal challenges, but selection and performance bias were observed across studies.

Conclusion

Interventions delivered TM have the potential, under certain conditions, to improve healthy lifestyle behaviors in adolescents. However, the rigor of studies varies and established theory and validated measures have been inconsistently incorporated.

Keywords: adolescent health, text messaging, health promotion, intervention studies

OBJECTIVES

Text messaging (TM) is a daily activity for adolescents. Approximately 78 percent of U.S. teens have a cell phone; of those, almost half (47%) own smartphones.1 Eighty-eight percent of adolescents use TM and more than half text daily. TM is the preferred channel of basic communication with friends.2 The pervasive nature of TM offers much potential as a strategy for delivering a health intervention to adolescents, owing to its ability to reach this group directly with health promotion messages.

Who are adolescents? The World Health Organization (WHO) definition is persons age 10–19 years.3 In 2012, there were 41,844,000 youth age 10–19 years in the U.S., representing 14% of the total U.S. population.4 Behavioral patterns established during adolescence help determine young people’s current health status and their risk for developing chronic diseases in adulthood.5 Healthy People 2020 identified an emerging issue in adolescent health—the increased focus on positive youth development interventions for preventing adolescent health risk behaviors, which include core indicators for healthy development, injury prevention, mental health, sexual health and substance abuse.6 These indicators align with the WHO definition of health promotion selected for this systematic review: the process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health, moving beyond a focus on individual behavior towards a wide range of social and environmental interventions.7

Given the ubiquity of TM among adolescents, it presents a potentially novel and valuable means for delivering health interventions to this group. TM as a communication channel enables researchers to directly reach adolescents in a relatively obtrusive way. Fully understanding the potential and limitations of TM requires spotlighting its role health interventions. Only one systematic review has examined the use of TM in interventions for enhancing healthy behaviors in a population that included adolescents.8 Militello and colleagues8 extracted data from seven articles published between 2006 and 2010; these articles were either randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-experimental studies. Groups receiving text messages experienced greater or increased blood glucose monitoring, energy expenditure, self-reported adherence and retention rates, as well as less risk for rejection after liver transplantation. Although the sample of articles in Militello and colleagues’ systematic review was small, their results of demonstrated the potential of using TM for interventions targeting adolescents.

Our multidisciplinary research team expands previous research by presenting a systematic review of intervention studies published between January 2011 and December 2014 that promoted healthy lifestyle behaviors among adolescents and used TM. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guided this systematic review; PRISMA suggests using the PICO approach to formulate research questions9. This systematic review targeted male and female adolescents between ages 10 and 19 years, at high or general risk of a health condition (P), who received a TM intervention (I) or similar adolescents who did not receive the intervention (C) designed to enhance healthy behavior or reduce health risk (O). To more fully understand the spectrum of evidence, this systematic review targeted a broad range of research methods (e.g., RCTs, quasi-experimental studies, observational studies) published in peer-reviewed journals. The research questions were: 1) What are characteristics of the adolescent sample and setting targeted for interventions delivered using TM? 2) How effective are interventions delivered using TM in improving healthy lifestyles? 3) How rigorous are the design and methods used in these studies? 4) What are challenges of using TM in interventions? 5) What bias is evident within and across studies?

METHODS

Article retrieval and eligibility determination, and data extraction, synthesis and evaluation occurred from December 2014 to July 2015.

Data Sources

The team librarian (SK) conducted searches of the PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and Web of Science databases using MeSH headings, descriptors and key terms listed in Table 1. Limits to the search were: English language, humans, published between 2011 and 2014, age 10–19 years. The search occurred during December 2014-January 2015. The initial search of these databases yielded 284 articles; three duplicates were removed for a total of 281 articles.

Table 1.

Search Strategy for Systematic Review

| Database | Search Terms |

|---|---|

| PubMed | “Cell Phones”[Mesh] OR “Computers, Handheld”[Mesh] OR ipad OR telemedicine OR mhealth OR “short message service:” OR tablet OR tablets OR “text messaging” OR “text messages” OR “media message service” OR smartphones OR “mobile technology” AND “Health Promotion”[Mesh] OR “Health Behavior”[Mesh] OR “Life Style”[Mesh] OR “Weight Reduction Programs”[Mesh] OR “Weight Loss”[Mesh] OR “Diet, Reducing”[Mesh] OR “Sunscreening Agents”[Mesh] OR “Sunburn”[Mesh] OR “Exercise”[Mesh] OR “Diet”[Mesh] OR “Skin Neoplasms/prevention and control”[Mesh] OR “patient compliance” OR “medication adherence” OR “smoking cessation” OR “tobacco use” OR sunscreen. |

| EMBASE | ‘mobile phone’/exp OR ‘mobile application’/exp OR iphone OR ipad OR ‘handheld computers’ OR ‘short message service’ OR tablet OR ‘text messages’ OR ‘text messaging’ OR ‘media message service’ OR smartphones OR ‘mobile technology’ AND ‘health promotion’/exp OR ‘health promotion’ OR ‘health education’/exp OR ‘health education’ OR ‘health behavior’/exp OR ‘health behavior’ OR ‘alcohol abstinence’/exp OR ‘alcohol abstinence’ OR ‘smoking cessation’/exp OR ‘smoking cessation’ OR ‘weight reduction’/exp OR ‘weight reduction’ OR ‘diet’/exp OR ‘diet’ OR ‘sunscreen’/exp OR ‘sunscreen’ OR ‘sunburn’/exp OR ‘sunburn’ OR ‘skin cancer’/exp OR ‘skin cancer’ OR ‘patient compliance’/exp OR ‘patient compliance’ OR ‘medication compliance’/exp OR ‘medication compliance’ OR ‘dietary compliance’/exp OR ‘dietary compliance’ |

| CINAHL | (MH “Wireless Communications”) OR (MH “Computers, Hand-Held”) OR smartphone OR iphone OR “short message service” OR ipad OR mhealth OR “short message service” OR tablet OR “text messaging” OR “text messages” OR “media message service” OR “mobile technology” AND (MH “Health Promotion”) OR (MH “Health Education”) OR (MH “Student Health Education”) OR (MH “School Health Education”) OR (MH “Life Style”) OR (MH “Life Style Changes”) OR (MH “Life Style, Sedentary”) OR (MH “Weight Reduction Programs”) OR (MH “Weight Control”) OR (MH “Diet”) OR (MH “Sunscreening Agents”) OR (MH “Skin Neoplasms”) OR (MH “Exercise”) OR (MH “Patient Compliance”) OR (MH “Medication Compliance”) OR (MH “Guideline Adherence”) OR (MH “Smoking Cessation”) OR (MH “Smoking Cessation Programs”) OR (MH “Alcoholic Intoxication”) OR (MH “Alcoholic Beverages”) OR (MH “Alcoholism”) |

| PsychINFO | (DE “Health Promotion”) OR (DE “Health Behavior”) OR (DE “Health Education”) OR (DE “Drug Abstinence” OR DE “Drug Education”) OR (DE “Alcohol Abuse” OR DE ”Alcohol Drinking Attitudes“ OR DE ”Alcohol Drinking Patterns” OR DE “Alcohol Intoxication” OR DE “Alcoholic Beverages” OR DE “Alcoholism”) OR (DE “Smoking Cessation”) OR (DE “Weight Loss”) OR (DE “Diets”) OR (DE “Cancer Screening”) OR abstinence OR sunscreen OR sunburn OR “skin cancer” OR compliance AND “cell phones” OR smartphones OR “mobile phones” OR “mobile technology” OR handheld OR ipad OR “text messages” OR “text messaging” OR “short message service” OR mhealth OR “media message service” OR “wireless”. |

| Web of Science | “health promotion “ OR “health behavior” OR “health education” OR drug OR alcohol OR smoking OR tobacco OR weight OR diet OR cancer OR sunscreen OR sunburn OR “skin cancer” OR compliance AND “cell phones” OR smartphone OR “mobile phones” OR iphone OR “mobile technology” OR handheld OR mobile OR “text messages” OR “text messaging” OR “short message service” OR mhealth OR “media message service” OR wireless. |

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

To be eligible for inclusion, articles had to be peer reviewed; describe original research (any type of study design); and focus or include analysis on adolescents between 10–19 years of age. The studies had to evaluate interventions delivered using mobile phone TM and that included a healthy lifestyle behavior as a main or outcome variable (e.g., diet and nutrition, medication/medical care adherence, physical activity, smoking and substance abuse, solar exposure).

Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA flow chart summarizing article eligibility and selection. Four team members divided and independently reviewed abstracts of the 281 articles to determine eligibility for data extraction. Ascertaining study samples that fit the WHO age range for adolescence (10–19 years) presented challenges. The team first checked the mean age of the participants. If the mean age was between 10 and 19 years, then the article was eligible for further review. If the mean age was not available, then 75% of participants had to be within the WHO adolescent age range. Reviewers scored the abstracts as “yes”, “no” and “maybe”, noting reasons for exclusion (see Figure 1). The articles receiving “maybe” scores described TM as a data collection method, not as a significant part of intervention delivery; thus the team reached consensus to eliminate those articles from further review. We also noted that two sets of authors10,11 had reported results from the same RCT; therefore, we included their most recent RCT report10 in the systematic review. A total of 254 articles were eliminated for reasons listed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Data Extraction

Data extraction from the selected 27 articles reflected the systematic review questions and PRISMA checklist items. We extracted the following information from each article: authors; study purpose; study design and data collection points; sample size, ethnicity, and age; a brief description of the TM intervention; main or outcome variables and measures; study results; and risk of bias. We assessed level of evidence for each study using criteria from Cochrane12 and Dearholt and Dang13 wherein Level 1 evidence was RCTs, Level 2 was quasi-experimental studies and Level 3 included observational studies. We did not assess Level 4 evidence because the requisite opinion of respected authorities and/or nationally recognized expert committees/consensus panels based on scientific evidence was not an eligibility criterion for the systematic review. Four team members divided and independently extracted data from articles that differed from than those assigned for the initial abstract review. The data extraction template was posted in a secure cloud storage service. This strategy allowed team members to continuously add data to the template and query other team members for additional review of complex articles or information entered into the template. The team met monthly throughout the data extraction period to discuss the most recent data additions and approve updates. Additionally, the two lead authors (LJL and SR) split articles from junior authors (CA and RM) to confirm their extracted information. Data extraction occurred from January 2015 through June 2015.

Data Synthesis

Synthesis occurred during July 2015. To determine sample and setting characteristics, the team synthesized information pertaining to gender, age, ethnicity, and geographic location for the sample in each article. To determine design and methodological rigor, the team noted the type of research design for each study. One team member compiled instruments or measures of each study’s main variables and secondary variables and reliability/validity estimations. Another team member reviewed each article to determine whether the intervention was based on established theories or conceptual frameworks that explain health behavior. To determine the effectiveness of TM as an intervention, two team members evaluated the results reported in each study related to the primary outcome variable(s). Tests of statistical significance were primarily used to determine the effectiveness of the intervention reported in each study. TM challenges were based on information provided by the authors in each article. The team reached consensus for the risk of bias in individual studies and across studies using Cochrane’s Collaboration’s Tool for Assessing Bias.14 This tool includes the domains of selection bias (random sequence generation, allocation concealment), performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), attrition bias (incomplete outcome data), reporting bias (selective reporting), and other sources of bias. The team further reviewed bias in individual studies using the ‘Risk of Bias’ assessment tool.14 We used Amico’s recommendation of maximum 30%–40% attrition in either study arm as a further indicator of attrition bias.15

RESULTS

Table 2 presents summary highlights of each of the 27 studies. Below, we state the synthesis of the results.

Table 2.

Results from Final Sample of Articles (n = 27)

| Authors/Purpose | Design & Sample | Intervention(Comparison/Control) | Main Outcomes | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Branson et al.33 Examine effects of TM appointment reminders to improve mental health treatment attendance |

Quasi-experiment, post-test only; Measurement: at 3-mos 48 patients (female, n = 24) in outpatient child mental clinic for low-income ethnic minority youth in New York City; (40% African American, 46% Latino, 14% multi-racial/other)Mean age: 15.1 yrs (± 1.5) |

IG (n =24): Received TM reminders for time/date of next appointment CG (n = 24): Historical control group from same clinic & time period; received no reminder TM |

Treatment attendance Self-reported satisfaction with intervention Presence of psychiatric disorder Reminder outcomes |

Attendance rates higher for IG than CG; after controlling for demographic & mental health factors, this difference remained significant (p = .02) IG received TM reminders before 88% (226/257) of sessions Most (82%–100%) participants reported satisfaction with TM reminders |

| Brown et al.16 Evaluate TM for delivering a health promotion intervention to adolescent, minority mothers |

Qualitative interviews; Measurement: 1 interview/mo × 6 mos 5 females attending a supplemental nutrition program in a Midwestern U.S. state (3 African American & 2 Latino) Mean age: 18.2 yrs (± 0.84) |

IG: Received essentials for postpartum care information by TM weekly × first 6 mos postpartum; educational content in the form of text &/or pictures | Intervention evaluation Intervention impact |

4 themes identified: social support; gaining information to overcome barriers; parenting validation; fit & benefits of using mobile phone for intervention Positive impact: all mothers provided breast milk to their children; 100% adherence to childhood immunization; all infants met well-baby care guidelines by 6 mos |

| Carroll et al.21 Assess feasibility & acceptability of a mobile phone glucose monitoring system for adolescents with diabetes & their parents |

Single-subject experiment Measurements: at 3 & 6 mos 39 patients (female, n =19) seen in an Indiana adolescent diabetes clinic Age range: 13–19 yrs |

IG: Received a Glucophone smartphone × 6 mos to enable testing/reporting blood glucose levels & interaction (via TM & voice call) with a nurse practitioner | System usability & satisfaction | TM helped participants remember to check their blood sugar |

| Chandra et al.17 Evaluate acceptability & feasibility of TM for promoting positive mental health & as a helpline among adolescent females |

Single-subject experiment; Measurements: at 1 mo & 1 mo after study conclusion 40 females living in urban India Mean age: 16.8 yrs (± 1.68) |

IG: Received 1 TM/day × 1 mo regarding positive mental health or helpline information; participants could call/text back with question or concerns | TM intervention perceptions | 62% liked receiving the TM; 50% said the TM made them feel happy 8% faced family objections about TM 62% preferred helpline TM over moodlifting TM |

| Cornelius et al.41 Examine a HIV prevention intervention delivered via mobile phones to adolescents |

Single-subject experiment; Measurements: at baseline, 7 & 19 wks 40 African Americans (female n = 21) recruited from community organizations & schools in a Southeastern U.S. state Mean age: 15.4 yrs (± 1.7) |

IG: Attended weekly in-person meetings × 7 wks; then received daily multimedia TM to serve as “boosters” × 3 mos | TM evaluation HIV-related knowledge & attitudes |

HIV knowledge increased after inperson meetings; no change from completion of meetings to conclusion of TM No change in attitudes toward condoms after meetings or TM Increased confidence in avoiding HIV after receiving TM No change in HIV risk behaviors over time Participants reliably responded to TM 97% said number of TM was “just right” |

| Dewar et al.10 Evaluate impact of a school-based multi-component program (NEAT Girls) on adolescent girls’ PA & sedentary behaviors |

RCT; Measurements: at baseline & 12 mos 357 girls attending 12 secondary schools in low-income communities in Australia (ethnicity not reported) Mean age 13.2 yrs (±.50) |

IG (n = 178; 6 schools): Received enhanced PA sessions, interactive seminars, student handbooks, nutrition workshops, pedometers, parent newsletters; TM to encourage PA, healthy eating, & decreased sedentary behavior. CG (n = 179; 6 schools): Wait-list CG |

PA Sedentary behaviors Social-cognitive mediators |

No group by time interactions for PA or social cognitive mediators Greater reductions in recreational computer use (p = .02) & sedentary activity (p = .04) in IG than CG |

| Fabbrocini et al.22 Evaluate adherence to therapy in acne patients using mobile phones & TM |

RCT; Measurement: at baseline & after 12 wks 160 patients (female, n = 87) enrolled from outpatient acne service (ethnicity not reported) Mean age 19.5 yrs (IG) 18.5 yrs (CG) |

IG (n = 80): Received 2 TM addressing acne × 2/day × 12 wks CG (n = 80): Did not receive TM |

Adherence QOL Satisfaction with TM |

Greater increases in adherence to treatment (p <0.0001) & improvement in QOL (p <0.0001) in IG than CG 95% of participants were “very much” or “quite” satisfied with TM |

| Haug et al.26 Test efficacy of an individually tailored TM intervention for smoking cessation in youth |

RCT; Measurements: at baseline & at 6 mos 755 students (female, n = 392) attending schools in Switzerland who were smokers at baseline Mean age 18.2 yrs (± 2.3) |

IG (n = 372; 90 classes): Received online assessment of individual smoking behavior, weekly TM assessment of smoking-related target behaviors, 2 weekly tailored TM, & integrated quit day preparation & relapse-prevention program CG (n = 383; 88 classes): Did not receive the intervention |

Smoking behavior change | No significant difference in 7 day abstinence rates, stage of change, or quit attempts Decreased mean number cigarettes smoked/day greater in IG than CG (p = .002) |

| Haug et al.27 Test appropriateness & effectiveness of an individually tailored TM intervention to reduce problem drinking in vocational school students |

Single-subject experiment; Measurements: at baseline & 12 wks 477 students (female, n = 111) attending 7 schools in Switzerland; 72% reported ≥1 instances of RSOD in past 30 days Mean age 18 yrs (±2.4) |

IG: Received 1–2 tailored TM/wk; TM tailored for age, gender, number of standard drinks per wk, & RSOD | RSOD behavior change | Decreased percentage had RSOD within the last mo from baseline for at least 1 RSOD occasion (p <.001) & > 2 RSOD occasions (p = .01) Decreased number of drinks in a typical wk (p = .002), percentage with 1+ alcohol-related problems in the last 3 mos (p = .009), & maximum number of drinks on a single occasion (p = .08) |

| Herbert et al.34 Investigate adolescents’ use of a diabetes TM program & determine whether certain groups more likely to respond to TM |

Single-subject experiment; Measurements: at baseline & 6 wks 23 adolescents (female, n = 11) with diabetes from a Mid-Atlantic U.S. state (78% White) Mean age 15.13 yrs (± 1.14) |

IG: Received 2 TM/day for majority of intervention; TM included information/tips & a request to respond to a specific question;TM topics included blood glucose monitoring, nutrition, PA, & sleep/mood | TM evaluation Glucose monitoring |

Participants responded to 78% of TM; most to nutrition TM, least to blood glucose TM Correlation between females & overall TM response rate & number personal TM sent/day (p < .05) Trend for participants with lower blood glucose to respond to more TM (p =.08). |

| Hingle et al.23 Evaluate a skin cancer prevention TM intervention among adolescents |

Single-subject experiment; Measurements: at baseline &12 wks 113 adolescents (female, n =60) from 3 Arizona middle schools who had completed a sun safety education program 2 wks prior to enrollment (ethnicity not reported) Age range: 11–14 yrs |

IG: Received 3 TM/wk × 13 wks; TM addressed skin cancer risk, sun protection benefits, & beliefs inconsistent with public health recommendation | Sun safety behavior, knowledge & attitudes | Increased self-reported use of sunscreen (p = .001), hats (p = .02), & sunglasses (P = .02) Greater consideration of sun avoidance during peak hours (p = .02) Increase overall skin cancer knowledge (P = .03) |

| Huang, Dillon et al.35 Compare a tailored versus generic weight management intervention among adolescent survivors of childhood leukemia |

RCT; Measurements: at baseline & 4 mos 38 overweight survivors (female, n = 23) off therapy for 2+ yrs recruited from a clinical trial (89.5% Hispanic, 2% black) Mean age 13 yrs (range 10–16) |

IG: (n=18): Received Web-&-TM information (tailored TM & queries) & weekly (mo 1) to biweekly (mos 2–4) counseling-based intervention CG (n=17): Received printed materials; biweekly phone call |

Weight/BMI PA Dietary intake Depression |

IG demonstrated greater, but not statistically significant, change in weight across study period compared to CG (p = .06) & no difference in changes in BMI, PA, or daily calories consumed IG reported reduced negative mood over time compared to CG (p = 0.01) |

| Huang, Terrones et al.36 Evaluate improved generic, Internet & mobile phone-delivered intervention on disease management, self-efficacy, & communication |

RCT; Measurements: at baseline, 2 mos, & 8 mos 81 patients (female, n = 44) with inflammatory bowel disease, cystic fibrosis, diabetes seen at tertiary care pediatric center (49% Hispanic, 9% black, 1% Native American) Mean age 17 yrs (range 12–20) |

IG: (n=38): Received access to a website for disease management, communication skills, & lifestyle tips + tailored TM CG: (n=37): Received monthly email messages on general health issues |

Disease self-management Health-related self-efficacy |

Group × time interaction for disease self-management (p = .02) & self-efficacy (p = .02); IG reported increased self-management & self-efficacy, but CG remained constant |

| Juzang et al.18 Evaluate a TM HIV prevention program among young adults |

Quasi-experiment; Measurements: at baseline, 3, & 6 mos 60 young black men in Philadelphia Median age 17 yrs (CG) 19 yrs (IG) |

IG (n=20): Received HIV prevention TM CG (n=19): Received nutrition TM Both groups: TM designed to increase positive outcome expectancies, norms, self-efficacy & intentions for condom use; received TM ×3/wk × 12 wks |

Sexual health knowledge, awareness, & risk-prevention behavior | Greater condom norms & sexual health awareness in CG than IG at all time points (no p values given) No changes in condom use intention |

| Lana et al.28 Assess impact of a Web-based intervention supplemented with TM to reduce TCBR |

RCT; Measurements: at baseline & 9 mos 2001 adolescents (female, n = 1081) attending Spanish & Mexican schools Age range: 12–16 yrs |

IG 1(n=177): Received access to website with information about main cancer risk behaviors IG 2 (n= 244): Same as IG1 + weekly TM to encourage adherence CG (n=316): Not specified |

Weight BMI (Kg/m2) Diet behavior: TCBR (smoking, unhealthy diet, alcohol use, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, sun exposure) |

TCBR scores reduced in all groups with significant drop in IG-1 & IG-2, but not CG (no p values reported) IG-2 intervention increased the probability of improving post-test TCBR score & giving up at least 2 risky behaviors |

| Lau et al.29 Evaluate Internet & TM intervention for promoting PA among adolescents |

Quasi-experiment; Measurements: at baseline & 8 wks 78 Chinese school children (female, n = 51) in Hong Kong Mean age IG 12.29 yrs (± 0.87) CG 13.26 yrs (± 1.14) |

IG (n=38): Received Internet- & stages of change-based PA program × 2/wk & daily TM on weekdays 5 TM types: motivational, informational, behavioral skills, reinforcement of PA benefits, & solutions for PA barriers CG (n=40): No intervention |

PA level over last 7 days SMR |

No time × condition interactions for PA or SMR; significant increases in PA (p = .05) & SMR (p = .01) in IG but not in CG Positive correlation between number of TM read & SMR (p < .01) |

| Love-Osborne et al.30 Evaluate feasibility of adding a health educator to school-based health center teams to deliver preventive services for overweight adolescents (TM used to reinforce goals between visits) |

RCT; Measurements: at baseline & 9 mos 165 adolescents (female, n = 86) with BMI ≥85% recruited from 2 centers (88.5% Hispanic) Mean age 15.7 yrs (± 1.5) |

IG (n=77): Received MI with goal-setting plus 2 TM/wk (1 individualized goal-related & 1 reminder to turn in log) CG (n=72): No intervention | Self-monitoring: of weight & lifestyle behaviors BMI (both groups) Cardiovascular fitness (IG) |

Greater proportion of CG decreased or maintained a stable BMI than IG (p =.025); Greater proportion of CG decreased BMI z-score by .1 or more than CG (p =.02) Sports participation higher in CG than IG (p = .02) |

| MacDonell et al.37 Assess feasibility of using ecological momentary assessment via TM on personal cell phones to measure medication adherence |

Single subject experiment; Measurement: at 14-days 16 African Americans (female, n = 7) with asthma enrolled from a large, urban hospital & university student health center Mean age 19.75 yrs (± 1.77) |

IG: Received TM daily to prompt a response about asthma medications/symptoms; sent event-based TM when they experienced asthma symptoms or took asthma rescue/controller medications | Asthma control Medication adherence Asthma symptoms Rescue medication use |

Adherence to controller medication from 0 – 14 days during the TM trial (M =8.69 ± 5.39)Asthma-related symptoms or limitations reported 28.1% of trial days but use of rescue medications 18.8% of days Responded to 78.5% of all time-based TM with a relevant response |

| Mulvaney et al.25 Improve diabetes adherence using individually tailored TM |

Quasi-experiment; Measurement: at baseline & 3 mos 28 adolescents (female, n = 15) with diabetes enrolled through a diabetes clinic (6% African American, 1% Hispanic & Pacific Islander) Mean age IG 15.9 yrs (± 2.9) CG 15.8 yrs (± 2.7) |

IG (n=23) Received TM tailored to participant’s reported top 3 barriers to adherence; 8–12 unrepeated TM/wk CG (n not stated): Historical controls from same clinic; matched with IG on age, gender, & HgbA1c values |

Glycemic control System usability & satisfaction |

Interaction between group × time (p < .01) for HgbA1c; values in IG were unchanged, but increased in CG. High system usability & satisfaction |

| Nguyen et al.19 Evaluate effectiveness of additional therapeutic contact as an adjunct to an extended weight-loss maintenance intervention |

Randomized trial (no control group); Measurement: at baseline, 12, & 24 mos 161 overweight & obese adolescents (gender not reported) seen in New Zealand community health centers (ethnicity not reported) Age range 13–16-yrs |

IG 1 (n=78): Received Loozit program including 7 × 75-min weekly group sessions; maintenance of 5×60-min quarterly adolescent booster group sessions IG 2 (n=79): Received Loozit + additional contact every 2 wks (overall 14 telephone coaching sessions & 32 TM &/or email messages) |

Baseline to 24-mos changes in BMI z-scores & waist: height ratio Psychosocialwell-being Dietary intake PA |

No statistically significant group effects or group-by-time interactions for primary outcomes & very few for secondary outcomes From baseline to 24 months, reductions in BMI & triglycerides in IG2 (p < .05). |

| Rhee et al.38 Develop & evaluate a comprehensive mobile phone-based asthma self-management aid for adolescents (mASMAA) |

Descriptive study with focus groups component; Measurement: at 2 wks Adolescents with asthma & their parents (16 dyads) (female, n = 6) recruited from emergency department & primary care clinics in a university medical center (40% black, 7% Asian) Mean age: 15 yrs (± 1.5) |

Intervention (2 wks); Received TM at a time chosen by each adolescent based on preference & medication schedule; adolescents encouraged to initiate asthma-related TM at least ×2/day | Asthma symptoms Asthma control level Activity level Frequency of rescue & other medication use & asthma control |

60% of adolescents experienced uncontrolled asthma for 2 + days during study Each adolescent on average submitted 19 self-initiated TM (range 3–38) regarding symptoms (69%), activity-(48%), & medication (10%) or 2 or more categories (29%) Intervention increased awareness of symptoms & triggers, improved asthma self-management, & medication adherence |

| Seid et al.20 Evaluate an intervention that integrates MI, problem solving skills training, & TM for adolescents with asthma |

RCT; Measurements: at baseline, 1 & 3 mos 29 adolescents (gender not described) with moderate & severe asthma) enrolled from an Ohio hospital (76.9% African American) Mean age 15.76 yrs (± 1.67) |

IG (n=12): Received 2 brief in person sessions 1 wk apart (asthma education, MI, problem skills training) & 1 mo of tailored TM CG (n=14): Received asthma education but no tailored TM |

Manipulation Mechanism of effect Efficacy (asthma symptoms, HRQOL) |

All participants found intervention appealing & acceptable At 1 & 3 mos, motivation, intentions, asthma symptoms, & barriers had clinically meaningful Cohen’s d medium to large effect sizes (.5–.96) |

| Shi et al.31 Test TM smoking behavior intervention to increase self-reported smoking abstinence & reduce daily cigarette consumption among adolescents |

RCT; (cluster randomization of 6 schools); Measurements: at baseline & 12 wks 179 Chinese adolescent smokers (female, n = 8) attending 6 vocational high schools Age range 16–19 yrs |

IG (n=76): Received daily tailored TM, interactive communication, & adjuvant online support CG (n=46) Received a self-help pamphlet |

Smoking cognitions, attitudes, & behaviors | Attitude toward disadvantages of smoking & mean reduction of cigarettes/day higher in IG (p < .01) Intervention effectively inhibited cigarette (p < .01) & nicotine dependence (p = .04) psychologically Difference in number of TM sent to investigator not significant No difference between groups in self-reported 7- & 30-day tobacco abstinence |

| Shrier et al.39 Evaluate the MOMENT intervention for marijuana use cessation among adolescents |

Single-subject experiment; Measurements: at baseline, 2 & 17 wks 27 patients (female, n = 19) in 2 adolescent clinics in a Northeastern U.S. city (44% black, 37% Hispanic) Median age 19 yrs (range, 15–24) |

IG (n=16) Received 2 brief motivational enhancement therapy sessions; 2 wks of mobile reports with TM supporting self-efficacy & coping strategies | Marijuana use & desire | TM motivated non-use of marijuana; were interesting, motivating, & helpful Average use events/day declined over the study Desire to use during & after a triggering context decreased from baseline to 3-mo follow-up (p < .0001 & p = .03, respectively) Non-significant change in motivational scale scores |

| Skov-Ettrup et al.24 Compare 2 versions of an Internet- & TM-based smoking cessation intervention |

RCT; Measurement: at baseline & 12 mos 2,030 newly registered users of xhale.dk (female, n = 1204) (ethnicity not reported) Mean age IG 19.4 yrs (± 3.1) CG 19.5 yrs (± 3.2) |

IG 1: Untailored intervention (n=371): Received TM about smoking cessation sent once daily × 5 wks; weekly TM × next 3 wks IG 2 Tailored intervention (n=383): Received weekly TM 4 wks before quit date & daily TM 1–3 days before quit date; then 2 tailored TM/day × 4 wks; then 4–5 TM/wk × 4 wks |

Smoking cessation perceptions & behavior | 79.8% chose to receive supporting TM No significant difference between IG-1 & IG-2 in changes in self-efficacy & beliefs about smoking from baseline to 12 mos follow-up |

| Ting et al.40 Investigate the effects of TM reminders on adherence to clinic visits & use of HCQ among adolescents with lupus |

RCT; Measurement: at baseline & 14 mos 70 patients (female, n = 65) in a lupus registry with childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus with unlimited access to TM (36% black)Mean age 18.6 yrs (± 2.5) |

All participants received visit adherence intervention: TM reminder sent 7, 3, & 1 day (s) prior to appointment IG 1: Received printed information about HCQ benefits & side effects IG 2: Received printed information + a standardized daily TM reminder regarding HCQ intake |

Clinical visit & medication adherence | 19% of patients were nonadherent to clinic visits at baseline; among them, there was improved visit adherence during the TM intervention (p = 0.01)After IG1 concluded, adherence rates declined (p = 0.02), but rates remained higher compared to baseline (p = 0.005 Medication adherence poor in more than two-thirds of cohort based upon HCQ blood levels, self-reports, & pharmacy refill data |

| Whittaker et al.32 Test mobile delivery of a depression prevention intervention for adolescents |

RCT; Measurement: at baseline & 12 mos 855 students (female, n = 584) (White European, Asian, Maori, Pacific Islander ethnicities) in New Zealand schools Mean age 14 yrs (range 13–17) |

IG: Received 2 TM (mixed formats)/day × 9 wks based on cognitive-behavioral therapy, followed by monthly TM & access to a mobile website CG: Received non-depression focused message (e.g., environment sustainability, cybersafety) |

Depression incidence Program perceptions |

Perceptions of being more positive & ridding of negative thoughts higher in IG vs CG (p < .001) 82.4% of participants reported finding the intervention to be useful |

Common abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CG = control/comparison group; HRQOL = health-related quality of life; HCQ = hydroxychloroquine; IG = intervention group; MI = motivational interviewing; PA = physical activity; QOL = quality of life; RCT = randomized controlled trial; RSOD = risky single-occasion drinking; SMR = Stage of motivational readiness; TCBR = total behavioral cancer risk; TM = text messages(ing); mo(s) = months; wk(s) = week(s); yr(s) = year(s)

Sample and Setting Characteristics

The grand mean age for the adolescents represented in the samples reporting mean age was 16.09 years. The majority of studies (n = 22; 81.5%) included males and females; however, three (11%) studies had a sample comprised solely of females,10,16,17 one (3.7%) had an all-male sample,18 and two (7.4%) did not report gender.19,20 The majority of ethnicities/races represented in the studies was non-Caucasian (n = 16; 59.3%), and included African American/black, Eastern Indian, Hispanic or Latino, Chinese, or a mix of ethnicities other than Caucasian. Five (18.5%) studies did not specify ethnicity in the sample.21–25 The setting for 10 (37%) studies was a school.10,17,23,26–32 Twelve (44.4%) studies20–22,25,33–40 were conducted in a clinic or hospital setting and five (18.5%) studies16,19,24,41 were community-based. Fifteen (55.5%) studies10,17,18,20,23,29–31,33–39 were conducted in an urban area whereas two (7.4%)16,21 were conducted in a rural area. Ten (37%) studies19,22,24–27,32,40–42 did not specify urban/rural setting.

Intervention Characteristics

The interventions reported among studies addressed a range of health topics including: obesity and physical activity,10,19,29,30,35 diabetes,21,25,34 smoking,24,26,31 asthma,20,37,38 mental health,17,32 HIV,18,41 multiple health topics,36,42 treatment attendance,33 motherhood,16 skin care,22 alcohol consumption,27 skin cancer,23 marijuana use,39 and lupus.40 The majority of studies reported interventions that attempted to promote healthy lifestyle behavior change (n = 19; 70.3%); the remainder promoted monitoring/adherence (n = 8; 29.6%).21,22,25,33,34,37,38,40

The intervention in thirteen (48.1%) consisted only of messages delivered via TM16–18,21–25,27,33,34,37,38 and 14 (51.8%) studies used TM along with other intervention components.10,19,20,26,29–32,35,36,39–42 Sixteen (59.2%) studies reported using one or more theories to guide the intervention.10,16,18–20,24–26,28,29,31,32,35,36,38,39 The most commonly cited theories were social cognitive theory,10,19,24,35,36 the theory of planned behavior,18,24 and the transtheoretical model.29,31

Effectiveness of Text Messaging as an Intervention

Although most studies tended to report at least some benefits for participants, there was variation in the effectiveness of the interventions included in the sample. Five studies focusing on monitoring or adherence showed at least some improvement or benefit from the intervention.22,25,33,37,40 Three other studies reported positive outcomes such as participants’ self-reports of intervention benefits21,38 or frequent responses to TM received during the intervention.34 Behavior change studies focused on reducing cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, or marijuana use also reported positive results. Two RCTs found a larger decrease in cigarettes smoked per day in the intervention than the control group.26,31 Two other studies showed significant decreases from the baseline for the number of drinks during a typical week27 as well as marijuana desire—though not marijuana use.39

Behavior change studies, which focused on topics related to obesity or physical activity as well as HIV prevention, had mixed results. The majority of studies addressing obesity or physical activity were RCTs. Of these, three studies found no significant differences between the intervention and control or comparison groups for physical activity10 or weight loss.19,35 One study, however, found a significant increase in self-reported physical activity in the intervention group relative to the control group.29 Although one study examining HIV prevention showed no change in attitudes toward condoms following in-person meetings or receiving TM,41 another quasi-experimental study found greater condom use in the intervention than control group.18

Of the studies in which the intervention consisted solely of messages communicated using TM, eight focused on monitoring/adherence and seven focused on behavior change. The studies focusing on monitoring/adherence reported greater attendance rates for mental health33 and lupus40 treatment, greater adherence to treatment regimens for acne22 and asthma,38 and no change in HgbA1c scores among diabetes patients.25 Three monitoring/adherence studies also reported that when directly asked, participants reported satisfaction with the TM intervention.21,22,33 Positive outcomes were reported in five of the behavior change interventions that relied solely on TM, including decreased alcohol consumption,27 increased sun-safety behaviors,23 and greater condom use.18 However, one other study showed no difference between groups that received tailored or non-tailored TM interventions for cigarette smoking beliefs or self-efficacy.24

The studies that included TM as one of multiple intervention components (n = 13; 48.1%) all promoted health behavior change. Seven of these studies demonstrated the efficacy of the intervention tested. Studies reported a significant increase in disease self-management,36 physical activity,29 asthma symptoms,20 and success in managing negative thoughts,32 as well as a significant decrease total behavioral cancer risk,42 body mass index,30 and cigarettes smoked per day.31 Yet three studies found no significant effects of the intervention on physical activity,19 HIV-related knowledge and risk behaviors,41 or weight loss.35 The two remaining studies reported more mixed results. One study found no difference in physical activity between the condition using TM and the control condition over time, but reported a greater reduction in sedentary activity and recreational computer use in the TM group than in the control group.10 Another study reported no difference in 7-day abstinence rates or quit attempts between a TM and control group, but a greater decrease in cigarettes smoked per day in the TM group.26

Adverse effects

Although we found no interventions that produced adverse effects, one study reported an intervention that was less effective than the no-intervention condition. Love-Osborne and colleagues30 found that the proportion of participants who maintained or decreased their BMI was greater in the control than intervention group. However, they also found increased sports participation in the control group, which they argue may have accounted for this result.

Sustained effects

There is no consensus for what constitutes a sustained effect of an intervention.43 Three studies in our systematic review10,24,32 followed participants to about one year post intervention. Of those, two reported that the intervention did not impact the lifestyle outcomes or potential mediators, largely owing to attrition10,24 and potential issues with intervention fidelity.10 At the time of publication of their study, Whittaker et al. did not report on the 12-month results of their intervention.32

Challenges of Using Text Messaging in an Intervention

About half of the articles noted some challenges using TM in an intervention. Phone or phone plan (if applicable) technical problems were easily resolved and lost or damaged phones were replaced either by the phone companies or the investigators. Some participants changed their phone numbers without informing the investigators, and subsequently were lost to long-term follow-up. Regardless of the method to disseminate TM (e.g., by individual phone or software programs), investigators did not know, with certainty, that TM sent to recipients had actually been read by them. Adolescents were less likely to respond to TM immediately in the morning when they were busy with school, and therefore, had to spend time in the evenings responding to TM from the initial daily round of texting. Boys texted less than girls, but girls were more likely to opt out of TM than boys. In studies that used tailored TM, investigators could not ascertain whether the tailoring or the frequency of TM improved outcomes. Adolescents preferred a variety of TM on a variety of topics each week versus one TM on one topic per week. They also preferred two-way versus one-way communication; however, investigators noted that the former required more staff time and resources. In studies using TM reminders, the constant TM reminders became repetitive. As the novelty wore off, participants ignored these reminders.

Methodological Rigor

Thirteen (48.1%) studies were RCTs,10,19,20,22,24,26,30–32,35,36,40,42 representing the highest level of evidence (Level 1). Four studies (14.8%) were quasi-experimental18,25,29,33.(Level 2 evidence) and the remaining 10 studies (37%) were single subject experiments17,21,23,27,34,37,39,41 or qualitative studies using interviews or focus groups16,38 (Level 3 evidence).

Description of reliability and validity of scales or instruments to measure outcomes of, or factors associated with TM interventions, varied among the studies. Six (22.2%) articles10,24,29,31,33,41 reported internal consistency (Cronbach α) of measurement scales ranging from 0.63 to 0.96, which ranges from unacceptable (lower coefficient) to acceptable or redundant (higher coefficients), depending on expert opinion.44 Two (7.4%) articles described instrument validity (e.g., convergent validity);29,41 however, authors of 10 (37%) articles stated that their selected scales previously were validated by others (referenced in the article), but did not provide specific information on psychometrics.10,18–20,25,32,36,39,41,42 Eleven (40.7%) articles contained no information on reliability and validity on one or more scales or instruments.17,21–23,26,27,30,35,40–42 Outcomes also were measured by author-developed checklists, diaries, single items or self-report inventories.24,30,31,33,38–40 The only measurements used in more than one study were indicators of disease status (e.g. HgbA1c, blood glucose, BMI), measures of physical activity (e.g., actigraph), and the patient activation scale.

Bias in Published Studies

In the 13 RCTs, trials, random sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), and blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) tended to be unclear or demonstrate high risk of bias (see Table 3). We noted several other forms of bias overall, including chronology bias (historical controls from same clinic);33 reporting bias such as detailed information about medical outcomes not reported,34 instrument not specified,18 or endpoints unclear and lacking findings on control group outcomes;25 detection bias in the form of knowledge of the allocated interventions by outcome assessors16 or outcome measurement likely to be influenced by lack of blinding;17,21 gender bias;24,27,29,31,32,38–41 confounding bias in the form of tailored TM and phone counseling not described or effect of mobile component unknown,35,36 author-noted confounders,30 or interviewer bias;38 attrition bias;18,19,31,42 and response bias in the form of self-report.10,23,29,32,33,35,37,41,42

Table 3.

Bias Evaluation for Randomized Trials (n =)

| Reference | Random Sequence Generation (Selection Bias) | Allocation Concealment (Selection Bias) | Blinding of Participants and Personnel (Performance Bias) | Blinding of Outcome Assessment (Detection Bias) | Incomplete Outcome Data (Attrition Bias) | Selective Reporting (Reporting Bias) | Other Bias | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dewar et al. 2014 | U | H | U | H | No details on randomization procedures | |||

| Haug et al. 2013a | H | |||||||

| Huang, Dillon 2014 | U | U | H | U | L | L | H | Tailored TM & phone counseling not described; effect of mobile component unknown |

| Huang Terrones 2014 | L | L | H | L | L | L | H | Tailored TM & phone counseling not described; effect of mobile component unknown |

| Lana et al. 2013 | U | U | H | U | H | L | L | No details on randomization procedures |

| Love-Osborne et al. | H | H | H | H | L | L | H | No details on randomization procedures; authors noted several confounders in both groups |

| Nguyen et al. | U | U | U | H | H | L | H | No details on randomization procedures; no true control group |

| Seid et al. | H | H | L | L | L | L | U | |

| Shi et al. | U | U | U | U | H | L | H | Potential recruitment bias with cluster randomization |

| Skov-Ettrup et al. | U | U | L | U | H | L | H | >60% attrition in both intervention groups; design does not allow conclusion of whether effect caused by tailoring or TM frequency |

Legend: H = high risk of bias; L = low risk of bias; U = unclear bias; TM = text messaging

CONCLUSIONS

Several conclusions might be drawn about the state of interventions promoting healthy lifestyle behaviors among adolescents using TM. Since the previous systematic review, 27 additional studies have been published. Although there was heterogeneity in the effectiveness of the studies examined in this review, most studies reported at least some positive outcomes. Studies focusing on monitoring and adherence, as well as studies where message delivery via TM was the only intervention component, tended to have the most positive findings. It is noteworthy that none of the studies in the sample involved adverse effects of the intervention. One study showed that the intervention group was less likely to lose or maintain their weight than the control group;30 however, there was no evidence that participants in the experimental group gained weight relative to the control group.

Despite the trend of reporting at least some positive outcomes, there were a large number of inconsistencies among the studies in the sample. The primary intervention outcomes or factors associated with TM differed for the vast majority of studies, including studies targeting similar topic areas (e.g., diabetes self-management, smoking cessation). Authors inconsistently used theory to inform intervention design. Only about half of the studies relied on established theories of health behavior change. Less than half of the articles reported internal consistency or validity of measures, which leads to concerns about inferences and conclusions drawn by the authors.45

There were several similarities and differences between this project and the previous systematic review8 that examined TM as an intervention to enhance healthy lifestyle. Both systematic reviews examined a variety of health behaviors. Beneficial outcomes were observed across the majority of studies included in both reviews. There was also a fair amount of variation in study quality across the two reviews. In regard to differences, Militello et al.8 reported on studies of children and adolescents; however all but one of their seven articles focused on adolescents within the age range of our targeted population. Militello et al.8 focused on RCTs and quasi-experimental studies, whereas the present systematic review also included two observational studies reporting on interventions. Most notably, the sample for the present systematic review was four-fold larger, likely reflecting the increasing numbers of studies on this topic and population since 2011. The increased sample size made it possible to better identify trends in the results of individual studies. Studies focused on promoting monitoring/adherence as well as changes in behavior related to alcohol and cigarette use tended to report positive outcomes. The results for studies of HIV prevention and physical activity were more mixed. Similarly, studies that consisted solely of messages communicated using TM tended to more consistently produce positive outcomes than studies using TM messages along with several other intervention components.

The trends identified in this project are important because they suggest that TM may be more useful for intervention delivery in some contexts than others. The degree to which TM is interwoven into adolescents’ everyday lives may make this technology a particularly useful tool for communicating reminders such as one might find in interventions promoting monitoring or adherence. TM can serve as a means to send relatively frequent but unobtrusive messages and promote compliance with routine activities. This potential may also make TM valuable for fostering the cessation of unhealthy behaviors such as alcohol and tobacco use. The ability to share brief but frequent messages is useful for communicating encouragement and reinforcement.

This systematic review had several strengths. We searched literature in several databases. Moreover, we used rigorous procedures based on PRISMA, including reliability checks of all articles by the lead authors of the systematic review. Limitations included combining the results of well-designed studies with less rigorously designed studies and combining heterogeneous studies (due to different populations, settings, interventions, or outcome measures). Slightly deviating from the procedure by Militello et al.8, we did not search Google Scholar or Cochrane Library databases. We did not include theses or dissertations as literature sources. Also, although it would have been desirable to consult comprehensive bibliographies in our search for articles, none could be located that addressed interventions delivered via TM to adolescents.

The results of this systematic review suggest the potential utility of TM interventions to enhance healthy lifestyle behaviors among adolescents. Across a relatively large sample of studies addressing a range of health issues and employing diverse research methodologies, there was consistent evidence that the TM interventions had at least some positive effects. More broadly, this review underscores the importance of efforts to synthesize the findings from health interventions delivered to adolescents using TM. Understanding how and with what effects TM might be incorporated in intervention efforts offers a potentially valuable mechanism for promoting intervention effectiveness. It seems likely that use of this technology for intervention delivery will only increase in the coming years. Those interventions conducted to date that have been rooted in established theory, adopted rigorous designs, used validated measures, and effectively controlled for bias offer valuable guides for future research.

Indexing Key Words.

Manuscript format: Literature Review

Content Focus:

Setting: Urban/rural, inpatient/outpatient/community, international

Health focus: Behavior Change/Communication/Adolescents

Strategy: Interventions delivered using text messaging for healthy lifestyle change

Target population: Adolescents between ages of 10 and 19 years

Target population circumstances: Any education, income, geographic location and race/ethnicity.

SO WHAT?

SO WHAT? Implications for Health Promotion Practitioners and Researchers

What is already known on this topic?

The previous systematic review of text messaging (TM) interventions to enhance adolescents’ healthy behaviors identified seven articles published prior to 2011—five showed effectiveness of TM interventions for diabetes self-management, treatment adherence, social support, and physical activity. Studies tended not to be theory-based or target vulnerable populations.

What does this article add?

This systematic review of 27 articles published between 2011 and 2014 provides new information on effectiveness of TM interventions targeting adolescents; adolescent and setting characteristics; levels of evidence, bias, and methodologic rigor; sole TM interventions versus when combined with other approaches; and challenges of using TM interventions.

What are the implications for health promotion practice or research?

TM interventions can improve healthy lifestyle in adolescents, including those in vulnerable populations. Adolescents easily engage in TM interventions, which may be most effective for monitoring/adherence behaviors and if they are the primary intervention component.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge funding support from the National Library of Medicine (NLM) Office of Communications and Public Liaison (Texting for Teens about Skin Cancer Prevention), The University of Arizona Cancer Center Support Grant (NIH/NCI 5P30 CA023074-36), and the University of Arizona Skin Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

Authors have no financial interests to disclose.

Contributor Information

Lois J. Loescher, The University of Arizona, College of Nursing, 1305 N. Martin | PO Box 210203, Tucson, AZ 85721-0203, Phone: 520-591-5898, Fax: 520-626-4062.

Stephen A. Rains, The University of Arizona, Department of Communication, 1103 E University Blvd, P.O. Box 210025, Tucson, AZ 85721, Phone: 520-626-3065, Fax: 520-621-5504.

Sandra S. Kramer, The University of Arizona, Arizona Health Sciences Library-Tucson, 1501 N. Campbell Avenue, PO Box 245079, Tucson, AZ 85724-5079, Phone: 520-626-6438, Fax: 520-626-2922.

Chelsie Akers, The University of Arizona, Department of Communication, 1103 E University Blvd, P.O. Box 210025, Tucson, AZ 85721, Phone: 520-626-1267, Fax: 520-621-5504.

Renee Moussa, The University of Arizona, Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health, 1295 N. Martin Ave., Drachman Hall, P.O. Box 245163, Tucson, Arizona 85724, Phone: 520-275-9119, Fax: 520-626-4062.

References

- 1.Madden M, Lenhart A, Cortesi S, Gasser U. Pew Research Internet Project Report Teens and Technology. 2013 http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/03/13/teens-and-technology-2013/ Accessed January 8, 2015.

- 2.Lenhart A, Ling R, Campbell S, Purcell K. Pew Research Internet Project Report Teens and Mobile Phones. 2010 http://www.pewinternet.org/2010/04/20/teens-and-mobile-phones/ Accessed January 8, 2015.

- 3.World Health Organization. Adolescent Health. 2015 http://www.who.int/topics/adolescent_health/en/

- 4.U.S. Census Bureau. Age and sex composition in the United States: 2012: Table 1. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrence RS, Gootman JA, Sim LJ. In: Adolescent health services: Missing opportunities. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Committee on Adolescent Health Care Services and Models of Care for Treatment P, and Healthy Development, editor. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Healthy People 2020. Adolescent health topics overview and goals. 2015 http://www.healthvpeople.gov/2020/topics-obiectives/topic/Adolescent-Health.

- 7.World Health Organization. Health promotion. 2015 http://www.who.int/topics/health_promotion/en/

- 8.Militello LK, Kelly SA, Melnyk BM. Systematic review of text-messaging interventions to promote healthy behaviors in pediatric and adolescent populations: Implications for clinical practice and research. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2012;9(2):66–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2011.00239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group TP Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews andMeta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4) doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dewar DL, Morgan PJ, Plotnikoff RC, Okely AD, Batterham M, Lubans DR. Exploring changes in physical activity, sedentary behaviors and hypothesized mediators in the NEAT girls group randomized controlled trial. J Sci Med Sport. 2014;17(1):39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lubans DR, Morgan PJ, Okely AD, et al. Preventing obesity among adolescent girls: One-year outcomes of the nutrition and enjoyable activity for teen girls (NEAT Girls) cluster randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2012;166(9):821–827. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cochrane Consumers Network. Levels of evidence. 2015 http://consumers.cochrane.org/levels-evidence. Accessed September 11, 2015.

- 13.Dearholt SL,DD. Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice: Models and Guidelines. 2nd. Indianapolis: Sigma Theta Tau International Honor Society of Nursing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011) The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors) Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amico KR. Percent total attrition: a poor metric for study rigor in hosted intervention designs. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(9):1567–1575. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.134767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown S, Hudson DB, Campbell-Grossman C, Yates BC. Health Promotion TEXT BLASTS for Minority Adolescent Mothers. Mcn-the American Journal of Maternal-Child Nursing. 2014;39(6):357–362. doi: 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandra PS, Sowmya HR, Mehrotra S, Duggal M. ‘SMS’ for mental health - Feasibility and acceptability of using text messages for mental health promotion among young women from urban low income settings in India. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;11:59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2014.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Juzang I, Fortune T, Black S, Wright E, Bull S. A pilot programme using mobile phones for HIV prevention. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2011;17(3):150–153. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.091107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen B, Shrewsbury VA, O’Connor J, et al. Two-year outcomes of an adjunctive telephone coaching and electronic contact intervention for adolescent weight-loss maintenance: the Loozit randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013;37(3):468–472. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seid M, D’Amico EJ, Varni JW, et al. The In Vivo adherence intervention for at risk adolescents with asthma: Report of a randomized pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2012;37(4):390–403. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carroll AE, DiMeglio LA, Stein S, Marrero DG. Using a cell phone-based glucose monitoring system for adolescent diabetes management. Diabetes Educ. 2011;37(1):59–66. doi: 10.1177/0145721710387163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fabbrocini G, Izzo R, Donnarumma M, Marasca C, Monfrecola G. Acne Smart Club: An educational program for patients with Acne. Dermatology. 2014;229(2):136–140. doi: 10.1159/000362809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hingle MD, Snyder AL, McKenzie NE, et al. Effects of a short messaging service-based skin cancer prevention campaign in adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;47(5):617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Skov-Ettrup LS, Ringgaard LW, Dalum P, Flensborg-Madsen T, Thygesen LC, Tolstrup JS. Comparing tailored and untailored text messages for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial among adolescent and young adult smokers. Health Education Research. 2014;29(2):195–205. doi: 10.1093/her/cyt112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulvaney SA, Anders S, Smith AK, Pittel EJ, Johnson KB. A pilot test of a tailored mobile and web-based diabetes messaging system for adolescents. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(2):115–118. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2011.111006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haug S, Schaub MP, Venzin V, Meyer C, John U. Efficacy of a Text Message-Based Smoking Cessation Intervention for Young People: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2013;15(8) doi: 10.2196/jmir.2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haug S, Schaub MP, Venzin V, Meyer C, John U, Gmel G. A pre-post study on the appropriateness and effectiveness of a Web- and text messaging-based intervention to reduce problem drinking in emerging adults. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2013;15(9):126–137. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lana A, del Valle MO, Lopez S, Faya-Ornia G, Lopez ML. Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial to improve cancer prevention behaviors in adolescents and adults using a web-based intervention supplemented with SMS. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:357. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lau EY, Lau PW, Chung PK, Ransdell LB, Archer E. Evaluation of an Internet-short message service-based intervention for promoting physical activity in Hong Kong Chinese adolescent school children: a pilot study. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2012;15(8):425–434. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Love-Osborne K, Fortune R, Sheeder J, Federico S, Haemer MA. School-Based Health Center-Based Treatment for Obese Adolescents: Feasibility and Body Mass Index Effects. Childhood Obesity. 2014;10(5):424–431. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi H-J, Jiang X-X, Yu C-Y, Zhang Y. Use of mobile phone text messaging to deliver an individualized smoking behaviour intervention in Chinese adolescents. Journal of Telemedicine & Telecare. 2013;19(5):282–287. doi: 10.1177/1357633X13495489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whittaker R, Merry S, Stasiak K, et al. MEMO-A Mobile Phone Depression Prevention Intervention for Adolescents: Development Process and Postprogram Findings on Acceptability From a Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2012;14(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Branson CE, Clemmey P, Mukherjee P. Text message reminders to improve outpatient therapy attendance among adolescents: a pilot study. Psychol Serv. 2013;10(3):298–303. doi: 10.1037/a0026693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herbert LJ, Mehta P, Monaghan M, Cogen F, Streisand R. Feasibility of the SMART project: A text message program for adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2014;27(4):265–269. doi: 10.2337/diaspect.27.4.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang JS, Dillon L, Terrones L, et al. Fit4Life: a weight loss intervention for children who have survived childhood leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(5):894–900. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang JS, Terrones L, Tompane T, et al. Preparing adolescents with chronic disease for transition to adult care: A technology program. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):e1639–e1646. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.MacDonell K, Gibson-Scipio W, Lam P, Naar-King S, Chen XG. Text Messaging to Measure Asthma Medication Use and Symptoms in Urban African American Emerging Adults: A Feasibility Study. Journal of Asthma. 2012;49(10):1092–1096. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.733993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rhee H, Allen J, Mammen J, Swift M. Mobile phone-based asthma self-management aid for adolescents (mASMAA): A feasibility study. Patient Preference and Adherence. 2014;8:63–72. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S53504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shrier LA, Rhoads A, Burke P, Walls C, Blood EA. Real-time, contextual intervention using mobile technology to reduce marijuana use among youth: A pilot study. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(1):173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ting TV, Kudalkar D, Nelson S, et al. Usefulness of cellular text messaging for improving adherence among adolescents and young adults with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(1):174–179. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cornelius JB, Dmochowski J, Boyer C, St Lawrence J, Lightfoot M, Moore M. Text-messaging-enhanced hiv intervention for african american adolescents: A feasibility study. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2013;24(3):256–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lana A, Faya-Ornia G, Lopez ML. Impact of a web-based intervention supplemented with text messages to improve cancer prevention behaviors among adolescents: Results from a randomized controlled trial. Preventive Medicine. 2014;59(1):54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ory MG, Lee Smith M, Mier N, Wernicke MM. The science of sustaining health behavior change: the health maintenance consortium. Am J Health Behav. 2010;34(6):647–659. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.34.6.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCrae RR, Kurtz JE, Yamagata S, Terracciano A. Internal consistency, retest reliability, and their implications for personality scale validity. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2011;15(1):28–50. doi: 10.1177/1088868310366253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carmines EG, Zeller RA. Reliability and validity assessment. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1979. [Google Scholar]