Abstract

Germline mutations in ATM (encoding the DNA-damage signaling kinase, ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated) increase Familial Pancreatic Cancer (FPC) susceptibility, and ATM somatic mutations have been identified in resected human pancreatic tumors. Here we investigated how Atm contributes to pancreatic cancer by deleting this gene in a murine model of the disease expressing oncogenic Kras (KrasG12D). We show that partial or total ATM deficiency cooperates with KrasG12D to promote highly metastatic pancreatic cancer. We also reveal that ATM is activated in pancreatic precancerous lesions in the context of DNA damage and cell proliferation, and demonstrate that ATM deficiency leads to persistent DNA damage in both precancerous lesions and primary tumors. Using low passage cultures from primary tumors and liver metastases we show that ATM loss accelerates Kras-induced carcinogenesis without conferring a specific phenotype to pancreatic tumors or changing the status of the tumor suppressors p53, p16Ink4a and p19Arf. However, ATM deficiency markedly increases the proportion of chromosomal alterations in pancreatic primary tumors and liver metastases. More importantly, ATM deficiency also renders murine pancreatic tumors highly sensitive to radiation. These and other findings in our study conclusively establish that ATM activity poses a major barrier to oncogenic transformation in the pancreas via maintaining genomic stability.

Introduction

Invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the most lethal solid malignancies. These tumors often arise from precancerous lesions called Pancreatic Intraepithelial Neoplasias or PanINs. Mutational activation of Kras is nearly universal in PanINs and PDAC, whereas inactivation of the tumor suppressors p16 Ink4a, p14 ARF (p19 Arf in mice), p53 and SMAD4 usually accompanies the transition from PanINs to PDAC1. Not surprisingly, familial cancer syndromes involving germline mutations in CDKN2A and TP53 enhance pancreatic cancer susceptibility. Likewise, the predisposition to pancreatic cancer increases in families with at least 2 affected first-degree relatives and these forms of the disease are classified as Familial Pancreatic Cancer (FPC)2. Similar to other cancers, some of the loci responsible for inherited high-risk PDAC include genes involved with DNA repair or chromosomal stability3.

DNA damage can occur by multiple routes, including endogenous stimuli, environmental agents or oncogene-induced replication stress4. Double-strand breaks (DSBs) are particularly toxic DNA lesions because they can foster mutations and chromosomal rearrangements that compromise genome stability4, 5. The DNA damage response (DDR) pathway senses specific DNA lesions, including those arising during replication stress, and orchestrates cellular responses needed to maintain genome integrity. The serine/threonine kinases ATM, DNA-PK (DNA-dependent protein kinase) and ATR (ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related) are members of the PIKK (phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase related kinase) family involved in mobilizing cellular responses downstream of DNA damage6. ATM is specifically recruited via the Mre11/Rad50/NBS1 (MRN) complex to regions where DSBs occur, and this event initiates ATM auto-phosphorylation and subsequent ATM-dependent phosphorylation of various substrates (including p53) that activate cell cycle checkpoints to induce cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, or senescence6, 7. ATM is central to genome stability because its activity prevents DNA damage from being converted to deleterious lesions, including oncogenic chromosomal rearrangements. Moreover, ATM has also been linked to other biological processes unrelated to DNA repair, such as metabolism and stress-responses8.

Biallelic mutations in ATM cause a severe, debilitating childhood neurodegenerative and immunodeficiency syndrome known as ataxia telangiectasia (A-T)7. A-T patients often become afflicted with cancer and their cells display enhanced chromosomal instability, high sensitivity to agents that cause DSBs, and impaired checkpoint activation or defective apoptosis7. In agreement with the observation that ATM germline mutations (which are prevalent in close to 1% of the population) increase the susceptibility to various types of cancer9, recent studies found that about 5% of patients with hereditary pancreatic cancer carry germline-inactivating mutations in this gene3, 10, 11. Furthermore, deep-sequencing methods also identified deleterious mutations in ATM in human pancreatic tumors classified as ‘genetically unstable’12. These and other results postulate that ATM activity poses a barrier to pancreatic cancer progression via maintaining chromosome stability. To test this hypothesis, we deleted Atm in pancreatic progenitors of the PDAC mouse model LSL-Kras G12D ;Ptf1a +/cre (also known as KC)13.

Results

Lack of ATM accelerates metastatic murine PDAC formation

We generated Ptf1a +/cre;ATM loxP/+ (pancreas Atm-heterozygous) and Ptf1a +/cre;ATM loxP/loxP (pancreas Atm-homozygous) breeders that were indistinguishable from their wildtype littermates (Supplementary Figure 1). These mice were intercrossed with LSL-Kras G12D;ATM loxP/+ mice to produce LSL-Kras G12D;Ptf1a +/cre, LSL-Kras G12D;Ptf1a +/cre;ATM loxP/+ and LSL-Kras G12D;Ptf1a +/cre;ATM loxP/loxP offspring, respectively named KC, KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ. Mice of the 3 genotypes were used in a survival study that was assembled to investigate the effects of ATM deficiency (partial or total) in KrasG12D-driven pancreatic tumor formation.

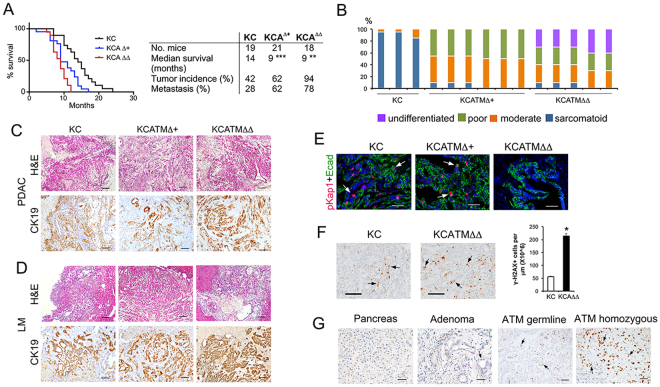

PDAC develops in only a fraction of KC mice through a process that is reminiscent to the human disease13. Accordingly, roughly 40% of KC mice in a C57/NMRI genetic background showed symptoms indicative of tumor formation (Supplementary Table 1) after 1 year of age and succumbed shortly thereafter. Post-mortem analyses revealed that in the KC group the incidence of pancreatic tumors and liver metastases was 42% and 28%, respectively (Fig. 1A). This tumor frequency parallels our findings in a previous study using KC mice of a similar C57/NMRI mixed background14. On the other hand, more than half of the KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ mice showed the former symptoms before 1 year of age and displayed an average life expectancy that was almost 5 months shorter than that of KC mice (the median survival was: 9 months [KCATMΔ+], 9 months [KCATMΔΔ], and 14 months [KC]; Fig. 1A). Results of post-mortem analysis identified pancreatic tumors in 62% of KCATMΔ+ mice and in nearly 100% of KCATMΔΔ mice (Fig. 1A). Additionally, this analysis also uncovered liver metastases in 62% of KCATMΔ+ mice and in 78% of KCATMΔΔ mice (Fig. 1A). These data demonstrate that ATM deficiency synergizes with KrasG12D to promote the formation of highly metastatic pancreatic tumors.

Figure 1.

ATM deficiency accelerates metastatic pancreatic cancer formation. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves show a dosage-dependent effect of ATM deficiency on survival in mice expressing pancreatic KrasG12D (***P < 0.001 [KC vs. KCATMΔ+]; **P < 0.01 [KC vs. KCATMΔΔ] Log rank-test). Partial or total ATM deficiency also increases tumor incidence and the frequency of liver metastasis. (B) Summary of tumor histology. (C) Representative images of pancreatic tumors stained with H&E or anti-cytokeratin antibodies. (D) Representative images of liver metastases stained with H&E or anti-cytokeratin antibodies. (E) Cells expressing phospho-Kap1 (red and arrows) are present in some areas of the pancreatic tumor epithelium (stained with anti-Ecadherin antibodies, green) in KC and KCATMΔ+ mice, and are absent in pancreatic tumors of KCATMΔΔ mice. (Scale bars are 40 µm). (F) Cells expressing γH2AX foci (arrows) are infrequent in KC pancreatic tumors and significantly more abundant in KCATMΔΔ pancreatic tumors (*P < 0.05; error bars represent ± SEM values; n = 3 individual tumors per genotype, unpaired 2-tailed t-test). (G) Human pancreatic specimens stained for γH2AX detection. Prominent γH2AX expression is observed in the tumor specimens carrying ATM germline heterozygous mutations and ATM somatic homozygous mutations. Scale bars are: 40 µm (E), 50 µm (G), 100 µm (C,D [CK-19], F) and 200 µm (C,D,H&E).

Histopathology analysis and cytokeratin-19 immunostaining of 3 KC metastatic tumors and of representative KCATMΔ+ (n = 6) and KCATMΔΔ (n = 5) tumors identified invasive PDAC with focal or extensive desmoplasia and variable morphology in all specimens (Fig. 1B,C). As has been described, KC tumors exhibited mostly sarcomatoid histology whereas KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ tumors had lesions with glandular histology and moderate or poor differentiation (Fig. 1B,C). These results indicate that ATM deficiency (partial or total) probably influences the spectrum of PDAC histology in KrasG12D-induced pancreatic tumors. Immunostaining results also showed scattered cells expressing the ATM target phospho-Kap16, 7 in both the KC and KCATMΔ+ pancreatic tumor epithelium (Fig. 1E), and absence of this protein in KCATMΔΔ pancreatic tumor epithelial cells (Fig. 1E). This finding indicates that the pancreatic tumors of our KCATMΔ+ mice retained a functional copy of Atm.

Activation of ATM by DSBs results in phosphorylation of the histone H2A variant H2AX (to generate γH2AX) and localization of this phospho-protein to sites of DNA damage. Since ATM activity has been implicated in oncogene-induced DNA damage responses4, 15 we examined the expression of γH2AX in ATM-proficient and ATM-deficient pancreatic tumors of our study group to compare the extent of DNA damage in those tissues. This analysis revealed a few cells expressing γH2AX in tumor specimens from KC mice (Fig. 1F), and considerably more cells expressing γH2AX in tumor specimens from KCATMΔΔ mice (Fig. 1F). Quantitative results corroborated that the pancreatic tumors of KCATMΔΔ mice had significantly more γH2AX+ cells than those tumors of KC mice (Fig. 1F). Similar analyses performed in human pancreatic specimens showed that γH2AX expression was virtually undetected in both, 1 control (healthy) specimen (Fig. 1G) and 1 specimen harboring a benign adenoma (Fig. 1G). In contrast, cells expressing γH2AX were noticed in focal areas of 1 tumor specimen from a patient with a heterozygous ATM germline inactivating mutation (Fig. 1G) and in large areas of 1 human pancreatic tumor that carried homozygous ATM somatic inactivating mutations (Fig. 1G). Thus, it is conceivable that ATM signaling is activated in pancreatic tumors of mice and humans to prevent the propagation of unrepaired DNA damage and to preserve genome integrity.

ATM-proficient and ATM-deficient primary tumors display a ‘pancreatic progenitor/classical’ phenotype and have similar alterations in Trp53 and p16INK4A/p19Arf expression

To further understand how ATM loss accelerates the formation of metastatic pancreatic tumors, we established low-passage cell cultures from primary PDACs and liver metastases of all 3 genotypes using published methods16–18. PCR analysis of RNA extracted from 3 KC cell lines, 3 KCATMΔ+ cell lines and 4 KCATMΔΔ cell lines showed that all KC lines expressed the Atm wildtype transcript, all KCATMΔΔ lines expressed the deleted (floxed) Atm transcript, and all KCATMΔ+ cell lines expressed both the wildtype and deleted Atm transcript (Supplementary Figure 2). Likewise, FISH analysis revealed that no large deletions involving the Atm locus had occurred in KCATMΔ+ cell lines generated from PDAC and liver metastases (Supplementary Figure 2). These combined results further indicate that Atm loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH) is not a prerequisite for the development of murine metastatic pancreatic tumors that already carry an inactive copy of Atm.

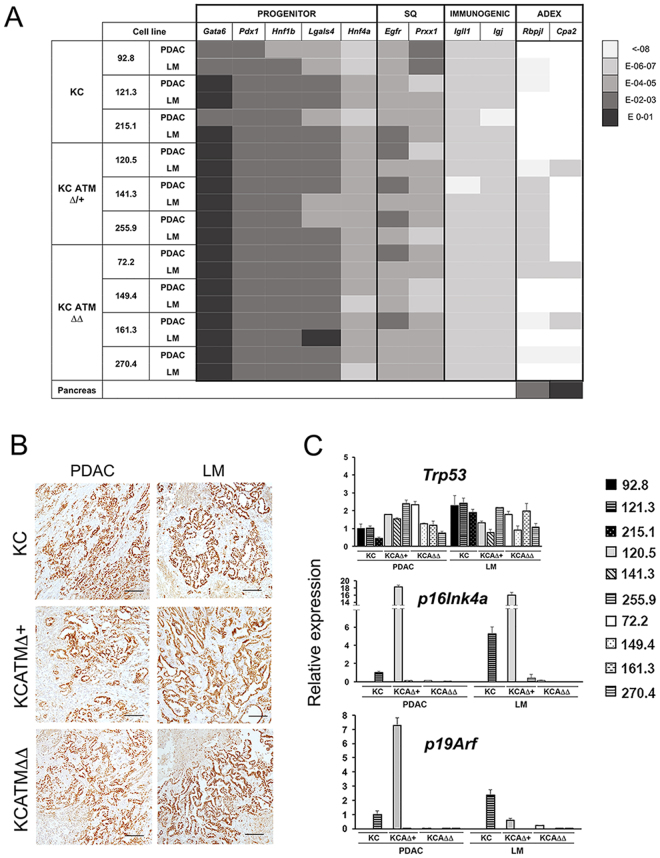

Two recent studies used genome wide expression methods to classify human pancreatic tumors based on their specific expression profile. In their study, Bailey et al.19 identified 4 subtypes of PDA that were named squamous, pancreatic progenitor, immunogenic and aberrantly differentiated endocrine exocrine or ADEX. Similarly, Collisson et al.20 identified 3 tumor subtypes that were named classical, quasimesenchymal and exocrine-like. With the exception of the immunogenic subtype, there is broad overlap amongst the transcriptome classifiers of the pancreatic progenitor/classical, squamous/quasimesenchymal and ADEX/exocrine-like subtypes19, 20. We subjected our primary tumor cell lines to qPCR analysis to investigate the expression of transcripts that the former studies used as tumor subtype classifiers. These results showed higher expression of the ‘pancreatic progenitor’ markers Pdx1, Hnf1β and Lgals4 19 across all our KC, KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ tumor cell lines (both from primary tumors and liver metastasis), in comparison to markers of the other subtypes (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table 2). Moreover, the ‘classical’ tumor marker Gata6 20 was uniformly expressed at high levels in all KC, KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ tumor cell lines (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table 2). Concurrent with the former results, immunostaining analysis of the ‘pancreatic progenitor’ marker Hnf1β showed extensive expression of this transcription factor in both primary tumors and liver metastases of all 3 genotypes (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, our generated tumor cell lines also expressed moderate to low levels of the ‘progenitor’ marker Hnf4 and the ‘squamous’ markers Egfr and Prxx1 (Fig. 2A). These results agree with the former histopathology results (Fig. 1B,C) showing that all the resected tumors presented variable glandular/sarcomatoid histology. Therefore, we conclude that the KrasG12D-driven tumors of our mouse models mainly acquired a pancreatic progenitor/classical phenotype irrespective of the status of ATM.

Figure 2.

Primary pancreatic tumor cell lines that lack ATM express Tp53 but not p16 Ink4a/p19 Arf. (A) Heat map showing the expression levels of PDA classifiers19, 20 in cell lines generated from KC, KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ primary tumors (PDAC) or liver metastases (LM). The color code (right) indicates the range of expression after normalizing with β-actin. (“Pancreas” is from a P7 mouse pancreas). (B) Immunostainig results demonstrate expression of Hnf1β in primary tumors (PDAC) and liver metastases (LM) of all 3 genotypes (Scale bar is 50 µm.) (C) QPCR results demonstrate retention of Tp53 expression in tumor cell lines established from KC, KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ primary tumors (PDAC) and liver metastases (LM), and loss of p16 Ink4a/p19 Arf expression in the majority of those cells. (Error bars represent ± SEM values of triplicate experiments).

We also investigated the expression of transcripts encoding the tumor suppressors p53, p16Ink4a and p19Arf 21 in our generated pancreatic cancer cell lines using qPCR. This analysis showed similar expression of Trp53 across all our generated KC, KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ cell lines (Fig. 2C). In addition, data from exon sequencing using genomic DNA or cDNA showed no mutations in Trp53 coding regions22 in any of the 3 KCATMΔΔ PDAC cell lines that we tested (data not shown). On the other hand, qPCR analysis revealed that most tumor cell lines had minimal or no expression of p16Ink4a/p19Arf (Fig. 2C), with the exception of one KC (121.3) cell line and one KCATMΔ+ (120.5) cell line. In conclusion, our combined qPCR results indicate that while ATM deficiency accelerates pancreatic cancer formation it does not confer a specific phenotype/genotype to pancreatic tumors.

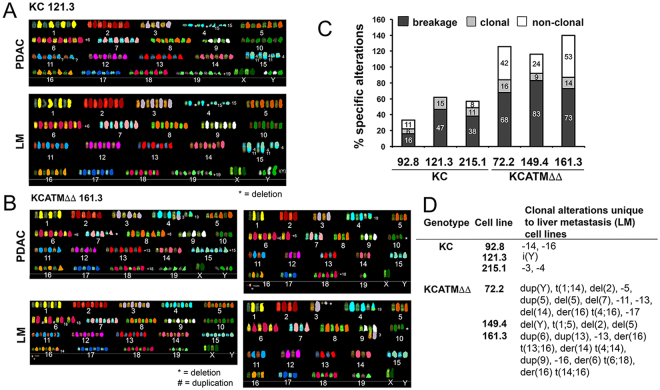

Lack of ATM increases chromosomal instability and promotes radiosensitization in pancreatic tumor cells

As we determined that ATM-deficient tumors have more widespread DNA damage than ATM-proficient tumors, we examined the extent of chromosomal alterations (an indicator of genome instability) in our established KC and KCATMΔΔ tumor cell lines using SKY analysis (Fig. 3A,B). SKY results showed similar proportion of clonal alterations (numerical/structural) in 3 individual KC primary tumor cell lines and 3 individual KCATMΔΔ primary tumor cell lines (6–15% and 9–16% respectively; Fig. 3C). In contrast, the frequency of non-clonal (random) structural alterations was higher in the KCATMΔΔ primary tumor cells in comparison to KC primary tumor cells (68–83% and 16–47%, respectively; Fig. 3C). In addition, the proportion of breakage type alterations (chromatid gaps/breaks) was also higher in the KCATMΔΔ primary tumor cells than in KCATMΔΔ primary tumor cells (24–53% and 0–11%, respectively; Fig. 3C). Furthermore, the comparison of clonal alterations between a primary tumor cell line and a liver metastasis cell line from 3 KC mice and 3 KCATMΔΔ mice underscored more numerical and newly acquired structural abnormalities in the ATM-deficient metastases in comparison to the ATM-proficient metastases (Fig. 3D). These collective SKY results conclusively demonstrate that ATM-deficiency increases chromosomal instability in KrasG12D-induced pancreatic tumors.

Figure 3.

ATM deficiency increases chromosomal alterations in pancreatic cancer cells. (A) Representative SKY images showing the chromosomal alterations of low-passage KC (121.3) and KCATMΔΔ (161.3) cells from both, the primary tumor [PDAC] and a corresponding liver metastasis [LM]). (B) Summary of SKY results showing that breakage and non-clonal chromosomal alterations are more frequent in KCATMΔΔ cultures than in KC cultures. (C) SKY data show that clonal alterations unique to liver metastases are more numerous in KCATMΔΔ tumor cells than in KC tumor cells.

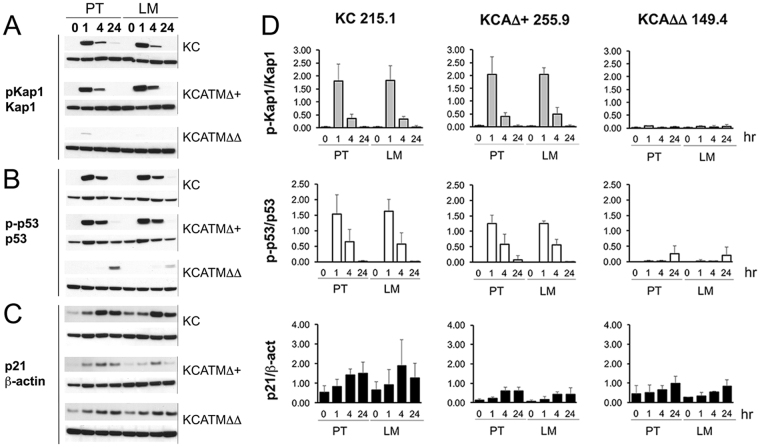

Tumors that have defects in DDR components are highly sensitive to agents that cause DNA damage4, and published studies showed that ATM-nullizygous cells display radiosensitivity7. Thus, we investigated if partial or total ATM-deficiency affects the response of pancreatic cells to DNA damage-inducing agents by exposing our KC and KCATMΔΔ primary tumor cells to X-ray or γ-irradiation (IR). As reported by others23, we detected activation of signals downstream of ATM (i.e., induction of the ATM-specific target phospho-Kap1, p53 [Ser-15] phosphorylation, and p21 increase) in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) exposed to 4Gy (1–4 hours post-IR) (Supplementary Figure 3). Similarly, those markers were also induced in KC 215.1 cells (either from primary PDAC or liver metastasis [LM]) 1–4 hours post-IR (4Gy; Fig. 4A–C). Interestingly, KCATMΔ+ 255.9 cells (PDAC and LM-derived) exposed to 4Gy IR also showed phospho-Kap-1 induction and upregulation of phospho-p53 and p21 proteins 1–4 hours post-treatment (Fig. 4A–C), and a similar result was also noticed in 2 additional KCATMΔ+ cell lines after irradiation (Supplementary Figure 3). In contrast, KCATMΔΔ 149.4 cells (both PDAC and LM) exposed to similar IR doses did not express phospho-Kap1 and only increased phospho-p53 slightly after 24 hours (although p21 induction was similar to that of 215.1 and 255.9 cells; Fig. 4A–C). These results were reproduced using the KC cell lines 121.3 and 92.8, and the KCATMΔΔ cell lines 72.2 and 161.3 (data not shown) and were validated using quantitative methods (Fig. 4D). Together, these data demonstrate that DNA-damage responses downstream of ATM are functional in KC and KCATMΔ+ pancreatic tumors, and absent in KCATMΔΔ pancreatic tumors.

Figure 4.

Atm-heterozygous pancreatic tumor cells activate ATM signals upon IR exposure. (A–C) Western blots show induction of phospho-Kap1 (A) and phospho-p53 (B) proteins in KC 215.2 tumor cells and KCATMΔ+ 255.9 tumors cells, 1–4 hours post-IR (4Gy). In contrast, phospho-Kap1 is largely undetected (A) and phospho-p53 is only slightly induced 24 hours post-IR (B) in KCATMΔΔ 149.4 tumor cells. (C) The expression of p21 increases in tumor cells of all 3 genotypes after exposure to 4Gy. (D) Quantitative Western blot results show similar p-Kap1/Kap1 protein ratios in KC 215.2 tumor cells and KCATMΔ+ 255.9 tumors cells, and lack of p-Kap1 induction in KCATMΔΔ 149.4 tumor cells, after 4Gy exposure. This analysis also shows very deficient phospho-p53/p53 ratio in KCATMΔΔ 149.4 irradiated cells compared to KC 215.2 and KCATMΔ+ 255.9 irradiated cells. Quantitative Western blots reveal more efficient induction of p21 in KC 215.2 cells than in KCATMΔ+ 255.9 and KCATMΔΔ 149.4 cells post-irradiation. Bars represent ± SEM values, n = 3 individual hybridizations per genotype). PT: primary tumor. LM: liver metastasis.

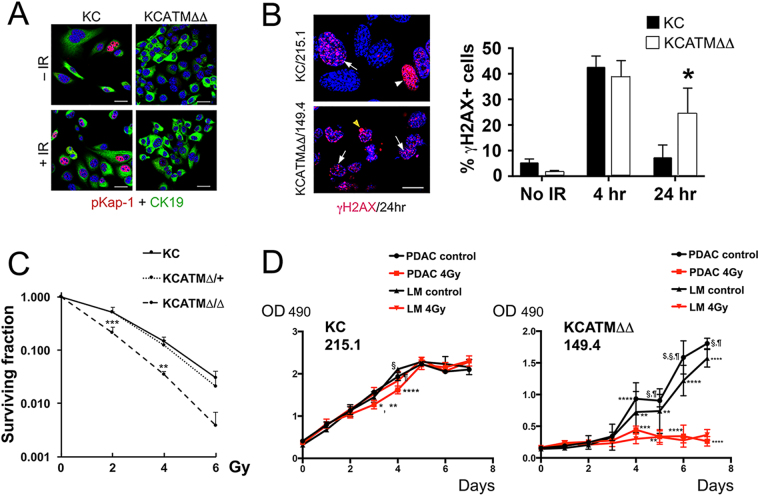

In agreement with the previous Western blot results, immunostaining analysis revealed expression of phospho-Kap1 in KC 215.1 cells exposed to 4Gy IR and lack of this protein in KCATMΔΔ 149.4 cells subjected to irradiation (Fig. 5A). In addition, immunostaining with anti- γH2AX antibodies uncovered numerous cells containing γH2AX+ foci in KCATMΔΔ 149.4 cultures (Fig. 5B) and less cells showing γH2AX+ foci in KC 215.1 cultures (Fig. 5B), 24h post-IR. Quantification of these results corroborated that significantly more γH2AX+ foci persisted in KCATMΔΔ 149.4 cells 24h after 4Gy IR exposure in comparison to KC 215.1 cultures. This data argued that the ability to repair IR-induced DNA damage is seriously compromised in ATM deficient PDAC cells. To further explore this notion, we compared the effects of IR-exposure in the survival of KC (215.1), KCATMΔ+ (255.9) and KCATMΔΔ (149.4) PDAC cells using a clonogenic assay. Our data showed similar survival response to increasing amounts of IR (0–6 Gy, X-ray) between KC cells and KCATMΔ+ cells (Fig. 5C), and significantly reduced survival of KCATMΔΔ cells subjected to the same IR regimen (Fig. 5C) in comparison to KC cells. To expand these observations, we used the MTT cell proliferation assay to compare the effects of irradiation between KC 215.1 cells (PDAC and LM) and KCATMΔΔ 149.4 cells (PDAC and LM). Similar to our previous clonogenic assay results (Fig. 5C), KC cells exposed to 4Gy γ-IR displayed radioresistance (Fig. 5D) and KCATMΔΔ 149.4 cells showed radiosensitivity (Fig. 5D) in a MTT assay. On the other hand, our MTT results revealed that KCATMΔ+ 255.9 PDAC cells are relatively radioresistant (Supplementary Figure 3). In conclusion, these novel results demonstrate that ATM deficiency confers a vulnerability (radiosensitivity) to pancreatic cancer cells that can be exploited therapeutically.

Figure 5.

ATM-deficient pancreatic tumor cells are radiosensitive. (A) Immunofluorescence analysis shows induction of phospho-Kap1 expression in KC 215.2 cells 4 hours after 4Gy exposure and lack of this protein in KCATMΔΔ 149.4 cells pre- and post-IR. (B) γH2AX foci increase at 4h and diminish 24 h post-IR treatment (4Gy) in KC 215.2 cultures. In contrast, γH2AX foci persist in KCATMΔΔ 149.4 cultures 24 h post-IR. (A representative γH2AX foci staining is indicated with arrows. The cell showing strong γH2AX staining [arrowheads] is probably apoptotic. *P < 0.05. Error bars represent ± SEM values; n = 3 cell lines, 2-Way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (C) Results of clonogenic assay show comparable viability responses of KC 215.2 and KCATMΔ+ 255.9 tumor cells subjected to different doses of irradiation, and significantly reduced cell viability of KCATMΔΔ 149.4 tumor cells after similar IR treatment. (P values are from KC 215.2 vs. KCATMΔΔ 149.4 cell comparisons; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Error bars represent ± SEM values of triplicate experiments, 2-Way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (D) Results of MTT assay show slightly reduced cellular response of KC 215.2 tumor cells exposed to 4Gy irradiation (KC 215.1: *P < 0.05 [PDAC 4Gy vs. LM 4Gy]; **P < 0.01 [PDAC control vs. 4Gy]; ****P < 0.0001 [PDAC Gy vs. LM ctrl.]; ¶ P < 0.01 [PDAC control vs. 4Gy]; § P < 0.01 [LM control vs. 4Gy]). MTT results also demonstrate increased sensitization of KCATMΔΔ tumor cells upon 4Gy exposure (day 4, **P < 0.01 [LM control vs. 4Gy]; ***P < 0.001 [PDAC control vs. 4Gy], ****P < 0.0001 [PDAC control vs. LM 4Gy]; day 5, **P < 0.01 [PDAC 4Gy vs. LM control and LM control vs. 4Gy]; §,¶ P < 0.0001 [PDAC control vs. 4Gy and PDAC control vs. LM 4 Gy]; day 6, ****P < 0.0001 [PDAC 4 Gy. vs. LM control and LM control vs. 4Gy]; $ P < 0.05 [PDAC control vs. LM control], § P < 0.0001 [PDAC control vs. LM 4Gy], ¶ P < 0.0001 [PDAC control vs. 4Gy]; day 7, ****P < 0.0001 [PDAC 4Gy. vs. LM control and LM control vs. 4Gy]; § P < 0.0001 [PDAC control vs. 4Gy], ¶ P < 0.0001 [PDAC control vs. LM 4Gy]. PDAC: primary tumor cells. LM: liver metastasis cells. P values are calculated before the cell cultures are confluent. Error bars represent ± SEM values; n = 3 replicates, 2-Way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). Scale bars: 25 µm (A), 12.5 µm (B).

ATM deficiency increases DNA damage in KrasG12D-induced pancreatic precancerous lesions

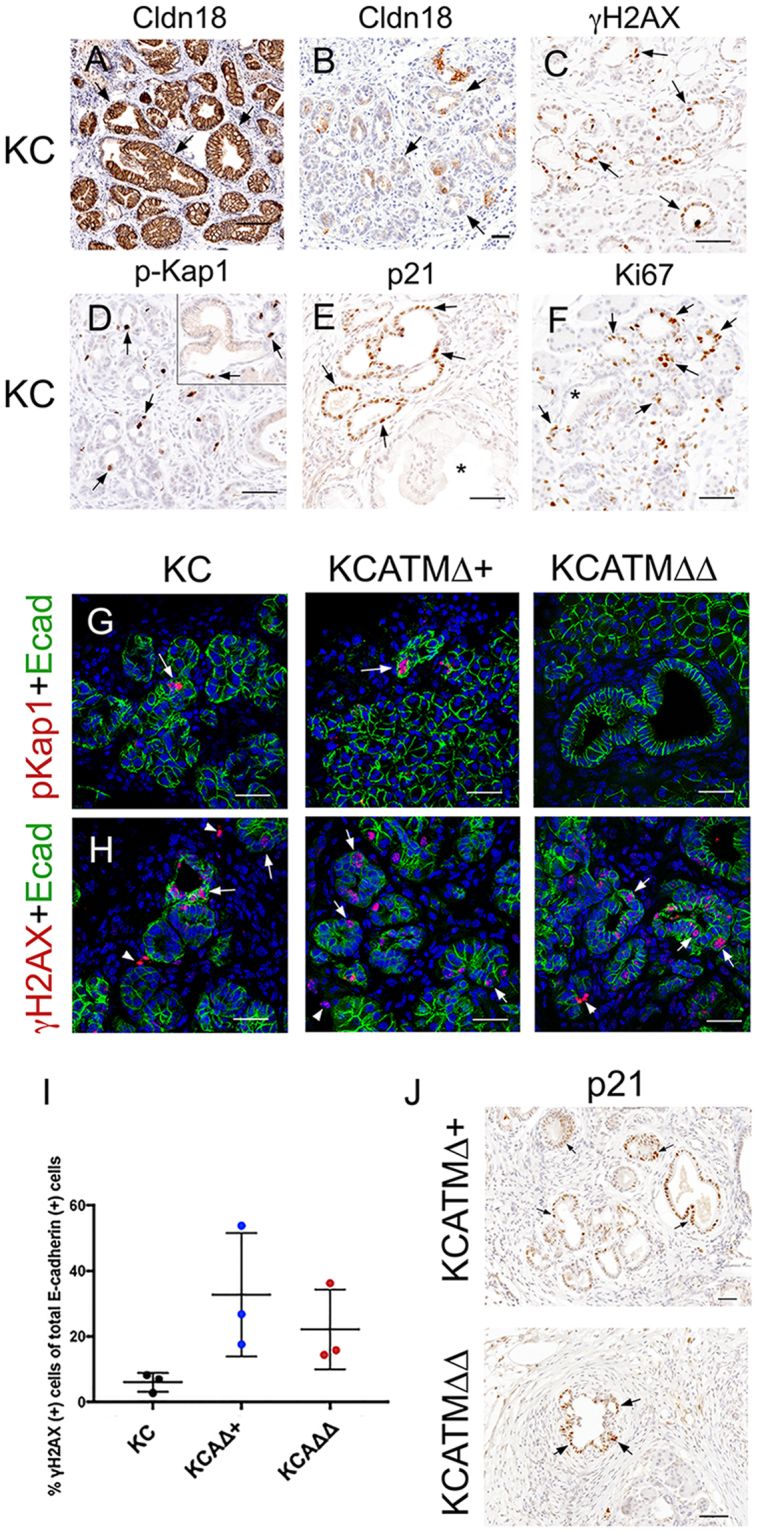

KrasG12D-driven murine pancreatic tumors arise from precancerous lesions that include small ductal lesions and mPanINs (Fig. 6A,B), and these epithelial entities are increasingly abundant in the pancreas of KC mice after 1 month of age14, 24–26. Interestingly, a published study27 reported activation of the ATM-CHK2 checkpoint and mounting DNA damage (in the form of γH2AX expression) in early human PanINs. Therefore, we investigated the expression of ATM-downstream effectors in precancerous lesions of KC mice using immunostaining methods. We detected expression of γH2AX (Fig. 6C), the specific ATM target phospho-Kap16, 7 (Fig. 6D), and the p53 target p21 (Fig. 6E), in small ductal lesions – and to a lesser extent in mPanINs – in pancreatic tissues of 2-months old KC mice. Additionally, we uncovered extensive expression of the proliferation marker Ki67 in small ductal lesions (Fig. 6F), and more limited expression of this marker in mPanINs (Fig. 6F), in 2-months old KC pancreata. These collective results demonstrate that ATM signaling is activated in murine pancreatic precancerous lesions in the context of cell proliferation and DNA damage.

Figure 6.

ATM-deficiency increases DNA damage downstream of KrasG12D in pancreatic precancerous lesions. (A,B) The abundance of cytoplasm and claudin-18 expression distinguish mPanINs (A, arrows) from small ductal lesions (B, arrows) in the pancreas of KC mice. (C–F) Markers of DNA damage (γH2AX, C), ATM signaling (phospho-Kap1, D), p53 activity (p21, E), and cell proliferation (Ki67, F) are expressed in small ductal lesions (arrows), and to a lesser extent in mPanINs (inset in D and asterisks in E,F), in KC pancreata. (G) The ATM-target phospho-Kap1 (red, arrows) is expressed in the pancreatic epithelium (Ecadherin+, green) of KC and KCATMΔ+ mice but not in this tissue of KCATMΔΔ mice. (H) Few cells express the DNA damage indicator γH2AX (red, arrows) in the pancreatic epithelium of KC mice. In contrast, γH2AX+ cells are more numerous in the pancreatic epithelium of KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ mice (arrowheads indicate non-epithelial cells). (I): Quantification of the fraction of Ecadherin+ cells that is also positive for γH2AX in KC, KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ pancreata (*P < 0.05; error bars represent ± SEM values; n = 3–4 individual specimens per genotype, ordinary one-way ANOVA). (J) Partial or total ATM deficiency does not affect the expression of p21 (arrows) in pancreatic precancerous lesions. Pancreatic tissues are from 2–4 months old mice. Scale bars: 25 µm (A,B); 50 µm (C–H,J).

The previous results prompted investigating whether, similar to our findings in tumors (Fig. 1F,G), ATM deficiency increases DNA damage in pancreatic precancerous lesions. Immunofluorescence results showed expression of phospho-Kap1 in the pancreatic epithelium (Ecadherin+) of 2–4 months old KC and KCATMΔ+ mice, and lack of this protein in the pancreas of KCATMΔΔ littermates (Fig. 6G). This data validated that Atm was effectively deleted in KCATMΔΔ pancreatic tissues. More importantly, double-immunofluorescence results revealed that ductal epithelial lesions exhibiting γH2AX+ foci were more abundant in KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ pancreata than in KC pancreata (Fig. 6H). Quantification of these results corroborated that γH2AX+ cells were more numerous in pancreatic epithelial cells of 2-months old KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ mice in comparison to those cells of KC littermates (Fig. 6I). These results conclusively establish that ATM activity is necessary to prevent the accumulation of excessive DNA damage in pancreatic precancerous lesions induced by KrasG12D. On the other hand, our finding that p21 was expressed in the pancreas of KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ mice (Fig. 6J) indicated that ATM activity is dispensable or redundant for the induction of p53-dependent checkpoints in pancreatic precancerous lesions.

ATM deficiency does not prevent KrasG12D-induced senescence but enhances mPanIN formation

Oncogene-induced senescence is a major tumor barrier in human precancerous lesions and it has been suggested that this process follows activation of a robust DDR28, 29. On the other hand, the role of ATM in oncogene-induced senescence is controversial. For instance, a published study demonstrated that ATM inhibition prevents Kras-induced senescence in human fibroblasts30. In contrast, a separate report showed that lack of ATM does not affect senescence induction in KrasV12-driven mouse lung adenomas31. These discrepancies prompted us to investigate the effects of ATM deficiency in senescence induction in murine KrasG12D-induced pancreatic precancerous lesions.

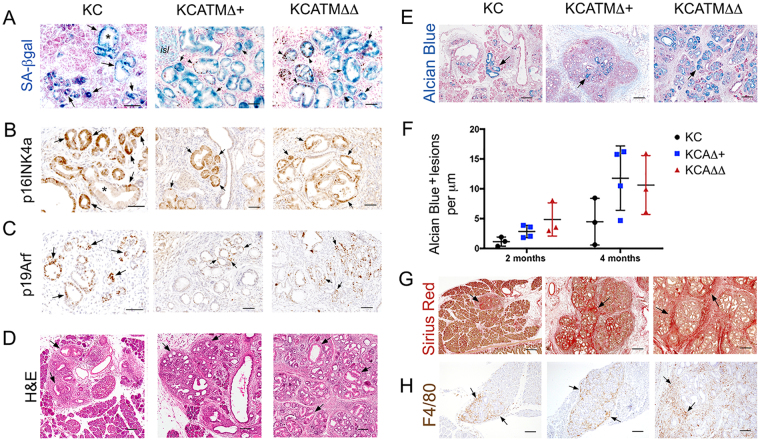

We stained the pancreas of 2–4 months old KC mice for SA-βgal detection to identify senescent cells. To complement this analysis, we also stained those tissues with antibodies recognizing p16Ink4a because a previous study reported concomitant expression of p16Ink4a and SA-βgal in mPanINs induced by KrasV12 32. We observed broad expression of SA-βgal in pancreatic precancerous epithelial lesions (Fig. 7A) of KC mice. In addition, we detected p16Ink4a and p19Arf (the 2 gene products of Cdkn2a) protein expression in both small ductal lesions and mPanINs (Fig. 7B,C) in the pancreas of KC mice. Interestingly, our SA-βgal staining results showed no differences in the expression of this marker amongst precancerous lesions of KC, KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ mice (Fig. 7A). Also, both p16Ink4a (Fig. 7B) and p19Arf (Fig. 7C) had comparable expression in pancreatic precancerous lesions of the 3 genotypes. These results demonstrate that ATM activity is dispensable for oncogene-induced senescence in KrasG12D-driven pancreatic precancerous lesions. In addition, our finding that precancerous lesions but not pancreatic tumors express p16Ink4a and p19Arf in our mouse models (Fig. 2C) further argues that the checkpoint controlled by these proteins is lost late in pancreas carcinogenesis”.

Figure 7.

ATM deficiency enhances mPanIN formation but does not prevent KrasG12D-induced senescence. (A–C) Partial or total ATM deficiency does not abolish the induction of senescence (A, SA-βgal staining) or the expression of p16Ink4a (B) or p19Arf (C), in KrasG12D-induced pancreatic precancerous lesions. (Arrows indicate small ductal lesions and asterisks indicate mPanINs). (D,E) ATM deficiency increases areas containing low-grade mPanINs (H&E staining, arrows in (D) and Alcian Blue staining, arrows in E) in a dosage-dependent manner in KrasG12D pancreata. (F) Quantification of Alcian Blue+ lesions in 2–4 months old KC, KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ pancreata demonstrates that low grade mPanINs are more abundant in tissues carrying partial or total ATM-deficiency (*P < 0.05; error bars represent ± SEM values; n = 3–4 individual specimens per genotype, ordinary one-way ANOVA). (G,H) ATM deficiency increases areas of fibrosis (Sirius red staining of collagen fibrils, arrows in G) and areas containing macrophage infiltrates (F4/80 immunostaining, arrows in H) in KrasG12D pancreata. Pancreatic specimens are from 2–4 months old mice. Scale bars: 200 µm (E,G); 100 µm (D,H); 50 µm (A–C).

We also stained the pancreata of our mouse models with H&E and uncovered focal areas harboring ductal epithelial structures surrounded by stroma in those tissues of 2 months old KC mice (Fig. 7D), and more extensive areas containing stroma and ductal epithelial lesions in the pancreas of KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ littermates (Fig. 7D). To further this observation, the pancreata of 2–4 months old KC, KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ mice was stained with Alcian Blue33 and the mPanIN lesions were counted. Results of this quantitative analysis corroborated that mPanINs were more numerous in the pancreas of both KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ mice than in this organ of KC littermates (Fig. 7E,F). Likewise, histologic and immunostaining results confirmed that the fibrotic stroma (Fig. 7G) and the macrophage infiltrates (Fig. 7H) were more prominent in the pancreas of KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ mice than in this organ of KC littermates. These results underscore that partial or total ATM deficiency directly or indirectly enhances KrasG12D-driven mPanIN formation and the associated inflammation.

Discussion

The activation of DNA damage responses downstream of oncogene-induced replication poses a major barrier to cancer progression and contributes to maintain genomic stability5, 34. ATM plays an important role in cancer protection because its activity engages the molecular machinery that repairs DSBs6, 7. In addition, ATM induces p53-dependent responses that promote cell cycle arrest, senescence or apoptosis to prevent the propagation of excessive DNA damage5, 15, 35. In this study we demonstrate that ATM activity is necessary for genome surveillance in the pancreas. First, we show that partial or total ATM deficiency cooperates with oncogenic Kras to promote highly metastatic murine pancreatic cancer. Second, we establish that lack of ATM causes persistent DNA damage in pancreatic tumors of mice and possibly also in pancreatic tumors of humans. Third, we show that ATM activity is necessary in established pancreatic tumors to prevent the accumulation of deleterious DNA lesions and to preserve genome integrity. These and other results suggest a model whereby oncogene-induced replication stress promotes DSBs in pancreatic precancerous cells and elicits activation of an ATM-mediated signaling cascade to repair the damaged DNA. In the absence of ATM activity, DNA damage (in the form of unrepaired DSBs) escalates, new oncogenic mutations are acquired, genomic instability accumulates, and pancreatic cancerous cells emerge. Thus, our study conclusively establishes that ATM’s main tumor suppressor role in the pancreas is to maintain genomic stability. Moreover, the marked differences in the number of clonal alterations uncovered between our KC and KCATMΔΔ metastatic cell lines indicate that ATM activity restrains PDAC in a locally advanced state, and that once its function is lost the accumulation of genomic instability enhances distant metastasis. This notion concurs with published data showing that human sporadic tumors that exhibit unstable genomes, chemoresistance, and poor prognosis (including those arising in the pancreas), frequently carry ATM somatic mutations9, 32.

Similar to our study, Russell et al.36 showed that loss of ATM accelerates KrasG12D-induced pancreatic cancer in mice. However, those authors did not report chromosomal alterations or excessive DNA damage in pancreatic tumors that lack ATM. Instead, they concluded that ATM deficiency enhances pancreatic tumor potential by increasing EMT and BMP4 signaling in precancerous lesions36. While these parameters were not evaluated in our analysis, a direct role of ATM in EMT or BMP signaling is yet to be proven. Moreover, our SKY results strongly indicate that the primary driver of metastasis in ATM-deficient pancreatic tumors is chromosomal instability. This conclusion concurs with the recognized role of ATM in sensing DNA damage6, 7, and with published results showing that aggressive, unstable forms of PDAC often carry somatic ATM mutations32. Therefore, our hypothesis that ATM activity is key to preserve genomic stability in pancreatic cells under oncogenic stress is well supported. On the other hand, we find intriguing that our generated ATM-deficient and ATM-proficient tumor cell lines shared a similar ‘pancreatic progenitor/classical’ subtype expression profile (including high Gata6 expression), because those features were found to correlate with better outcome in PDA patients30, 31. Thus, it is possible that the increased genomic instability of ATM deficient tumors contributes to disable some of the transcriptional networks and gene programs operating in ‘pancreatic progenitor/classical’ tumors. Addressing this and other outstanding questions using genome-wide approaches is necessary to understand how ATM deficiency increases pancreatic metastatic disease.

Our new finding that murine pancreatic precancerous lesions express phospho-Kap1 coincides with similar observations in humans27 and argues that ATM is activated very early during KrasG12D-driven oncogenesis, probably in response to DSBs induced by replication stress4, 35. However, ATM could accomplish functions that do not involve signaling DNA damage in pancreatic precancerous lesions. For instance, ATM activity has been implicated in cellular redox homeostasis independent from its role in DNA damage responses8. Also, the activation of DNA damage (by ROS) and ATM signaling was shown to suppress the production of cytokines37. A potential regulatory role of ATM in both cellular redox and cytokine production in pancreatic tissues would agree with our finding that both KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ mice present increased DNA damage, extensive fibrosis and abundant macrophage infiltrates in the pancreas. Moreover, overabundance of cytokines could enhance a stromal reaction that favors the formation of mPanINs38, 39. Investigating these issues should help disclosing how ATM activity protects precancerous pancreatic cells from oncogenic transformation.

The discovery that our generated ATM-deficient pancreatic tumor cells expressed p53 but not p16Ink4A/p19Arf concurs with the observation that KrasG12D-induced murine pancreatic tumors have frequent loss of p16Ink4A and p19Arf or loss of p53, but not simultaneous loss of the 3 tumor suppressors21. Moreover, our findings also agree with a whole-genome sequencing study22 showing more frequent mutations or losses of CDKN2A (6/9 tumors) than TP53 (3/9 tumors) in human pancreatic tumors carrying ATM mutations. The preferential loss of p16Ink4A/p19Arf expression over that of p53 suggests that the need to inactivate the p53/p21 barrier is bypassed in ATM-deficient tumors because p53 is a target of this kinase. In contrast, inactivating p16Ink4A/p19Arf is probably necessary in KrasG12D-induced tumors to overcome the checkpoints induced by these tumor suppressors and the senescence barrier imposed by the p16Ink4A-Rb pathway21. Whether genomic instability facilitates the inactivation of p16Ink4A/p19Arf in ATM-deficient pancreatic tumor cells or other mechanisms are involved in p16Ink4A/p19Arf downregulation warrants further investigation (e.g., ATM loss could enable the DNMT1-mediated methylation of the p16 Ink4A promoter)40.

The results from FISH, gamma-irradiation and qPCR analyses showed that our generated KCATMΔ+ pancreatic cancer cells retained a functional wildtype Atm allele. These findings are intriguing because in a study reporting germline heterozygous ATM mutations in FPC kindreds the analyzed tumors showed ATM LOH inactivation3. These results argue that transformed human and murine pancreatic cells respond differently to the dosage of ATM, although it is also possible that in our KCATMΔ+ tumor cells additional mutations or oncogenic events bypassed the need to inactivate the wildtype Atm allele. While these hypotheses remain to be tested, it is noteworthy that similar to our study other investigators reported acceleration of PDGF-induced murine gliomas in the context of Atm heterozygosis without LOH41.

In addition to providing new information on DNA damage-induced ATM activation in the pancreas, and the effects of ATM deficiency in the context of KrasG12D expression, our study introduces a novel mouse model that should be clinically relevant. First, the pancreatic tumors of our mice have the genetic features of some aggressive forms of human pancreatic cancer, as it was shown that patients carrying tumoral loss of ATM and normal p53 expression tend to have very poor prognosis after tumor resection42. Second, the fact that our established ATM-deficient murine pancreatic tumor cells display radiosensitivity is quite relevant because other studies showed that human pancreatic tumor cells become radiosensitized upon treatment with an ATM inhibitor43 or ATM siRNA44. Therefore, our mice are suitable models to test drugs or combined treatments that confer synthetic lethality (e.g., PARP1- or ATR inhibitors45, 46) to pancreatic tumors carrying ATM-deficiencies.

In summary, our study determined that the main tumor suppressor role of ATM in the pancreas is to maintain genomic stability. This finding agrees with the canonical genome surveillance role of ATM and has clinical relevance, since human pancreatic tumors that carry ATM somatic mutations have ‘unstable genomes’ and are very difficult to overcome. In addition, our discovery that ATM signaling is activated in pancreatic precancerous lesions to prevent the propagation of unrepaired DNA suggests that pathologic conditions that promote DNA damage (e.g., chronic inflammation)47 could increase the risk of pancreatic cancer in individuals carrying ATM germline mutations.

Methods

Mice

Generation of Atm +/LoxP, Ptf1a +/cre and LSL-Kras G12D mice was described previously13, 48, 49. Mice were maintained in a mixed C57BL/6/NMRI genetic background. Animals were monitored at least twice weekly for signs of illness and euthanized when they had early signs of distended abdomen or lethargy. Weight loss was not observed at this stage. At necropsy hemorrhagic ascites and several metastatic nodules in the liver, diaphragm and pleural surfaces (mainly in KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ animals) always accompanied the distended abdomen. Mice were treated according to the criteria outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the St Jude Animal Care and Use Committee.

Human tumor specimens

The patients were enrolled under an IRB approved protocol for bio banking at the University of Michigan, which allows banking the tissue and blood specimens for future research. Patient #1 (46 years old, female, deceased) had metastatic PDA and was treated with gemcitabine/abraxane for 6 months, and subsequently with FOLFOX (Folinic acid, 5-FU, Oxaliplatin), gemcitabine/cisplatin + olaparib and FOLFIRI (Folinic Acid, 5-FU, Irinotecan) in a Phase I clinical trial. A fine needle aspiration biopsy was performed and genomic analysis results identified ATM somatic homozygous inactivating mutations (I396fs*10) in the tumor. Patient #2 (66 years old, male) had a borderline resectable PDA and was treated with neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX (5-FU, leucovorin, irinotecan, oxaliplatin) and gemcitabine plus radiation therapy. A core biopsy of the resected tumor was performed and genomic analysis identified a heterozygous ATM germline inactivating mutation (c.4143dupT). All experimental protocols were approved by the University of Michigan Clinical Research Ethics Committee and all procedures were performed in accordance with the approved guidelines and regulations.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining on paraffin and frozen was performed as previously described14. All primary and secondary antibodies used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG antibodies were detected by using the VECTASTAIN Elite ABC kit (Vector Laboratories). Prolong Gold with DAPI (40,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Invitrogen) was used for nuclear staining. Images were obtained with a Zeiss Axioskop 2 microscope, or with a confocal/Multiphoton laser-scanning Zeiss LSM 510 META microscope.

SA-β-gal/Ki67 staining

Detection of SA-β-gal was performed using published methods50. Following this step, sections were post-fixed with 4% PFA (10 min, RT) and processed for immunostaining using anti- Ki67 antibodies. Sections were counterstained with nuclear Fast Red.

Morphometric analysis

Low and high power confocal images were analyzed using Image J and γH2AX-Ecadherin double positive cells were counted using the “cell counter” plugin. High power confocal images were used to count γH2AX+ foci in at least 100 cells from each primary cell line. Low magnification images covering the entire pancreas were captured using the Aperio scanner and Alcian Blue positive lesions were counted using Image J (3 or more sections spanning the whole pancreas were used per genotype).

Primary cell lines

Primary pancreatic ductal cell cultures were established from KC, KCATMΔ+ and KCATMΔΔ primary and metastatic tumors, according to established protocols16–18. Cells were passaged serially 4–5 times to insure homogeneity before analysis. All in vitro analyses were performed on low passage number lines (<P8).

Quantitative PCR and RNA isolation

Total RNA was extracted using TRizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and PureLink mini kit (Invitrogen). The purity and integrity of the isolated RNA were determined using a spectrophotometer NanoDrop One/One (Thermo Fisher Scientific). cDNA synthesis was performed using Protoscript first strand cDNA synthesis kit (New England Biolabs) and random hexamers according to the manufacturer’s instructions. iTaq™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-rad) was used for qPCR and the detection was performed in a Mastercycler® RealPlex2 (Eppendorf). Gene expression was normalized against the expression of β-Actin using the Relative Standard Curve Method. Results were expressed as the Mean ± SE (standard error) from three different replicates. The primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 4.

γ-irradiation of cultured cells

Cells after passage 4 were plated in 24-well plates at a concentration of 50,000 cells per well. The cells were irradiated using a 137 Cs-source (Gammacell 40-exactor, MDS Nordion, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) at a dose of 4Gy and collected at the designated time points.

Clonogenic assay

Clonogenic assays on tumor cells exposed to different x-ray doses (RS 2000 X-ray Irradiator, Rad Source) were performed following published methods51. Briefly, confluent 100 mm plates of primary tumor cells from KC, KCATMΔ/+ and KCATMΔΔ mice were trypsinized, counted with a hemocytometer and diluted with complete media to obtain 160, 400 or 800 cells per well of each genotype respectively. Colonies were stained with crystal violet after 7 days, and those containing at least 50 cells were counted as surviving colonies. The plating efficiency and the survival fraction for each cell line after each treatment were calculated as described in Franken et al.51. Survival was calculated in comparison with non-treated samples, using an average of three determinations of the same dose rate of cells (±SE).

Western blot

Cells (~800,000) from primary tumor and liver metastasis were seeded in 60 mm plate dishes. After 22 hours the culture medium was changed and 2 hours later the cells were irradiated (4Gy) using an RS 2000 X-ray Irradiator (Rad Source). Cell extracts were collected at 0, 1, 4 and 24 hours post-irradiation. Cells were harvested in cold PBS, and then lysed in 250 µL of RIPA Buffer (Sigma Aldrich). Protein quantification was performed using the Bradford reagent (Bio Rad) and samples were prepared by adding NuPAGE LDS Sample Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and β -mercaptoethanol. 30 µg of whole cell extracts were loaded into 10% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and electrophoresed at 110 volts in NuPAGE MES SDS Running Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Proteins were transferred to PDVF membrane using 10% Methanol NuPAGE Transfer Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 16 hours at 30 volts and 4 °C. Primary antibodies were incubated 2 hours at room temperature and secondary donkey Horseradish Peroxidase-conjugated antibodies (Jackson) were incubated 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were developed using SuperSignal™ West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The primary antibodies used here are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Three independent hybridizations were performed for each primary antibody. The corresponding bands were scanned and quantified by densitometry using the CLIQS software from TotalLab (www.http://totallab.com/). The median ratio of p-p53/total p53, p-Kap1/total Kap1 or p21/β-actin from the three experiments ± SE (standard error) was calculated.

Histochemistry

Alcian Blue staining for visualization of PanINs’ mucinous content and Picrosirius Red staining for collagen fibers were performed according to manufacturer’s instructions (Abcam). Immunohistochemically and histochemically stained slides were further scanned with an Aperio® slide scanner (Leica).

Immunofluorescence of cultured cells

Cells were cultured, fixed and stained as previously described14.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH)

Cells were grown to 60–70% confluence, treated with colcemid (0.02 µg/mL) for a 4 h incubation at 37 °C, and harvested using routine cytogenetic methods. The cells were then trypsinized for 5 minutes at 37 °C and centrifuged at 900 RPM for 5 minutes. The cell pellet was resuspended in 0.075 M KCL for 8 minutes at RT and then centrifuged at 600 RPM for 5 minutes, resuspended in 3:1 Carnoy’s fixative (3 parts methanol: 1 part acetic acid), and incubated for 15 minutes at RT. The cells were centrifuged at 600 RPM for 5 minutes, resuspended in Carnoy’s fixative, and incubated for 10 minutes at RT. The cells were spread onto a glass slide using a Pasteur pipette. The slides were air dried at RT. Purified DNA from Atm (RP23-456L9/9A5.3) was labeled with a red-dUTP (AF594, Molecular Probes) and purified DNA from a chromosome 9 control (RP23-284E19/9A5.2) was labeled with a green-dUTP (AF488, Molecular Probes) by nick translation. The probes were combined and hybridized to interphase and metaphase cells derived from the two samples using routine cytogenetic methods. Cells were stained with DAPI and total of one hundred interphase nuclei were scored for the number of red and green signals per cell.

Spectral Karyotype (SKY) Analysis

Slides containing cells in metaphase were prepared as described before. Spectral karyotyping of chromosomes was performed using a mouse SkyPaint probe (Applied Spectral Imaging, Carlsbad, CA) per the manufacturer’s recommendation. Probes were detected using Applied Spectral Imaging’s concentrated antibodies detection kit (CAD), as described by the manufacturer. Cells were stained with 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and images were acquired with a Nikon Eclipse E600 fluorescence microscope equipped with an interferometer (Spectra Cube: Applied Spectral Imaging) and a custom designed filter cube (Chroma Technology Corporation, Rockingham, VT). HiSKY software version 7.2 (Applied Spectral Imaging) was used for SKY analysis.

Mutation analyses of Trp53 and Cdkn2a

For Trp53 exon sequence analysis, genomic DNA was isolated from 3 KC and 3 KCATMΔΔ primary cell lines (pancreatic tumor and liver metastases, <P8) using the Wizard DNA purification kit (Promega). For Trp53, p16 Ink4a and p19 Arf cDNA sequencing, total RNA was extracted and cDNA was synthesized as described13. Accuprime high fidelity polymerase (Life Sciences) was used for PCR. PCR products were purified using the QIAquick gel extraction kit (Qiagen science, Maryland, USA), and submitted for sequencing using the same forward and reverse primers used for amplification. Supplementary Table 5 lists the primers used for this analysis.

MTT assay

Human cell lines and murine PDAC and liver metastasis primary cell lines maintained in the logarithmic phase of growth were trypsinized, counted, and plated at 100 cells/well in 96 well plates in a total volume of 100 ml of complete medium. Twenty-four hours later, cells were irradiated and viability was assessed starting on the same day and for 6–7 more days using the Cell Titer Aqueous Viability assay (Promega) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell titer aqueous is based on an improved version of the standard MTT assay where the MTS tetrazolium compound is bioreduced by cells into a colored formazan product that is soluble in tissue culture medium in contrast to medium-insoluble MTT product. Therefore, the colorimetric assessment of proliferation can be performed in one step.

Statistical Analyses

In all graphs, data are presented as mean ± SEM. Significance was accepted at a P value < 0.05. PRISM software was used to perform statistical analysis for all datasets. For survival analysis the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was performed. For comparison of Alcian Blue or γH2AX staining results in the 3 genotypes, ordinary ANOVA one-way was performed. For Clonogenic and MTS data from different time points, ANOVA 2-way analysis was performed with Bonferroni’s test for multiple comparisons.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank Gerald Zambetti, Gerard Grosveld, Martine F. Roussel and Athanasios Vassilopoulos for providing reagents and expert advice; Angelica S. Martinez Ramirez, Emin Kuliyev, Rob Jeffers, Yasmine Valentin-Vega, Vanessa Enriquez-Rios and Susanna Downing for technical support; P. Johnson for the Aperio slide scanning; the Veterinary Pathology Core, the Cytogenetics Core, and the Cell and Tissue Imaging Core of St. Jude. We also thank the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC), The Hirshberg Foundation and Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine, for funding these studies.

Author Contributions

B.S.-P. and Y.D. conceived, designed and directed the study. B.S.-P. and Y.D. wrote the manuscript. Y.D. performed the majority of experiments. D.E. and M.-Y.C. performed clonogenic, qPCR, immunostaining and Western blot experiments. K.R., and L.P. performed Western blot and immunofluorescence experiments. V.V. and M.V. conducted the S.K.Y. and FISH analyses. J.R. evaluated the mouse tumors. J.Y. performed the Trp53 and Cdkn2a sequencing experiments. V.S. and L.B. provided and stained the human pancreatic specimens. P.M.K. provided expertise, mice and reagents for the study.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-11661-8

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hansel DE, Kern SE, Hruban RH. Molecular pathogenesis of pancreatic cancer. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2003;4:237–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.4.070802.110341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartsch, D. K., Gress, T. M. & Langer, P. Familial pancreatic cancer–current knowledge. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology9, 445–453, doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2012.111 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Roberts NJ, et al. ATM mutations in patients with hereditary pancreatic cancer. Cancer discovery. 2012;2:41–46. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Molecular cell. 2010;40:179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halazonetis TD, Gorgoulis VG, Bartek J. An oncogene-induced DNA damage model for cancer development. Science. 2008;319:1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1140735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiloh, Y. ATM and related protein kinases: safeguarding genome integrity. Nature reviews. Cancer3, 155–168, doi:10.1038/nrc1011 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.McKinnon PJ. ATM and the molecular pathogenesis of ataxia telangiectasia. Annu Rev Pathol. 2012;7:303–321. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011811-132509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiloh, Y. & Ziv, Y. The ATM protein kinase: regulating the cellular response to genotoxic stress, and more. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology14, 197–210, doi:10.1038/nrm3546 (2013). [PubMed]

- 9.Choi M, Kipps T, Kurzrock R. ATM Mutations in Cancer: Therapeutic Implications. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:1781–1791. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts NJ, et al. Whole Genome Sequencing Defines the Genetic Heterogeneity of Familial Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer discovery. 2016;6:166–175. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant RC, et al. Prevalence of germline mutations in cancer predisposition genes in patients with pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:556–564. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biankin, A. V. et al. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature491, 399–405, doi:10.1038/nature11547 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Hingorani SR, et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:437–450. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00309-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drosos Y, et al. Prox1-Heterozygosis Sensitizes the Pancreas to Oncogenic Kras-Induced Neoplastic Transformation. Neoplasia. 2016;18:172–184. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gorgoulis, V. G. et al. Activation of the DNA damage checkpoint and genomic instability in human precancerous lesions. Nature434, 907–913, doi: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v434/n7035/suppinfo/nature03485_S1.html (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Schreiber FS, et al. Successful growth and characterization of mouse pancreatic ductal cells: functional properties of the Ki-RAS(G12V) oncogene. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:250–260. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hingorani SR, et al. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ijichi H, et al. Aggressive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice caused by pancreas-specific blockade of transforming growth factor-beta signaling in cooperation with active Kras expression. Genes & development. 2006;20:3147–3160. doi: 10.1101/gad.1475506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailey, P. et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature531, 47–52, doi:10.1038/nature16965 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Collisson, E. A. et al. Subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their differing responses to therapy. Nat Med17, 500–503, doi:10.1038/nm.2344 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Bardeesy N, et al. Both p16(Ink4a) and the p19(Arf)-p53 pathway constrain progression of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5947–5952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601273103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waddell, N. et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature518, 495–501, doi:10.1038/nature14169 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Li, H. et al. The HINT1 tumor suppressor regulates both gamma-H2AX and ATM in response to DNA damage. J Cell Biol183, 253–265, doi:10.1083/jcb.200711150 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Zhu L, Shi G, Schmidt CM, Hruban RH, Konieczny SF. Acinar cells contribute to the molecular heterogeneity of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:263–273. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basturk O, et al. A Revised Classification System and Recommendations From the Baltimore Consensus Meeting for Neoplastic Precursor Lesions in the Pancreas. The American journal of surgical pathology. 2015;39:1730–1741. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Westmoreland JJ, et al. Dynamic distribution of claudin proteins in pancreatic epithelia undergoing morphogenesis or neoplastic transformation. Dev Dyn. 2012;241:583–594. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koorstra, J. B. et al. Widespread activation of the DNA damage response in human pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Mod Pathol22, 1439–1445, doi:10.1038/modpathol.2009.114 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Di Micco, R. et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is a DNA damage response triggered by DNA hyper-replication. Nature444, 638–642, doi:10.1038/nature05327 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Childs, B. G., Durik, M., Baker, D. J. & van Deursen, J. M. Cellular senescence in aging and age-related disease: from mechanisms to therapy. Nat Med21, 1424–1435, doi:10.1038/nm.4000 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Bartkova, J. et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is part of the tumorigenesis barrier imposed by DNA damage checkpoints. Nature444, 633-637, doi:10.1038/nature05268 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Efeyan A, et al. Limited role of murine ATM in oncogene-induced senescence and p53-dependent tumor suppression. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collado, M. et al. Tumour biology: senescence in premalignant tumours. Nature436, 642–642, doi:10.1038/436642a (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Kopp JL, et al. Identification of Sox9-dependent acinar-to-ductal reprogramming as the principal mechanism for initiation of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:737–750. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Negrini, S., Gorgoulis, V. G. & Halazonetis, T. D. Genomic instability–an evolving hallmark of cancer. Nature reviews. Molecular cell biology11, 220–228, doi:10.1038/nrm2858 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Macheret M, Halazonetis TD. DNA replication stress as a hallmark of cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2015;10:425–448. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012414-040424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russell, R. et al. Loss of ATM accelerates pancreatic cancer formation and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Commun6, 7677, doi:10.1038/ncomms8677 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Harbort CJ, et al. Neutrophil oxidative burst activates ATM to regulate cytokine production and apoptosis. Blood. 2015;126:2842–2851. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-05-645424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rachagani S, et al. Mucin (Muc) expression during pancreatic cancer progression in spontaneous mouse model: potential implications for diagnosis and therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2012;5:68. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-5-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi, C. et al. Fibrogenesis in pancreatic cancer is a dynamic process regulated by macrophage-stellate cell interaction. Lab Invest94, 409–421, doi:10.1038/labinvest.2014.10 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Shamma A, et al. ATM mediates pRB function to control DNMT1 protein stability and DNA methylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2013;33:3113–3124. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01597-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Squatrito M, et al. Loss of ATM/Chk2/p53 pathway components accelerates tumor development and contributes to radiation resistance in gliomas. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:619–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim H, et al. Having pancreatic cancer with tumoral loss of ATM and normal TP53 protein expression is associated with a poorer prognosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:1865–1872. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hennig, J., McShane, M. P., Cordes, N. & Eke, I. APPL proteins modulate DNA repair and radiation survival of pancreatic carcinoma cells by regulating ATM. Cell Death Dis5, e1199, doi:10.1038/cddis.2014.167 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Ayars M, Eshleman J, Goggins M. Susceptibility of ATM-deficient pancreatic cancer cells to radiation. Cell Cycle. 2017;16:991–998. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2017.1312236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmitt A, et al. ATM Deficiency Is Associated with Sensitivity to PARP1- and ATR Inhibitors in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2017;77:3040–3056. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Knittel, G. et al. Two mouse models reveal an actionable PARP1 dependence in aggressive chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nat Commun8, 153, doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00210-6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Kiraly O, Gong G, Olipitz W, Muthupalani S, Engelward BP. Inflammation-induced cell proliferation potentiates DNA damage-induced mutations in vivo. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1004901. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee, Y. et al. ATR maintains select progenitors during nervous system development. EMBO J31, 1177–1189, doi:10.1038/emboj.2011.493 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Kawaguchi, Y. et al. The role of the transcriptional regulator Ptf1a in converting intestinal to pancreatic progenitors. Nature genetics32, 128–134, doi:10.1038/ng959 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Dimri GP, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9363–9367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Franken, N. A., Rodermond, H. M., Stap, J., Haveman, J. & van Bree, C. Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro. Nat Protoc1, 2315–2319, doi:10.1038/nprot.2006.339 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.