Abstract

Omega-3 fatty acids may influence human physiological parameters in part by affecting the gut microbiome. The aim of this study was to investigate the links between omega-3 fatty acids, gut microbiome diversity and composition and faecal metabolomic profiles in middle aged and elderly women. We analysed data from 876 twins with 16S microbiome data and DHA, total omega-3, and other circulating fatty acids. Estimated food intake of omega-3 fatty acids were obtained from food frequency questionnaires. Both total omega-3and DHA serum levels were significantly correlated with microbiome alpha diversity (Shannon index) after adjusting for confounders (DHA Beta(SE) = 0.13(0.04), P = 0.0006 total omega-3: 0.13(0.04), P = 0.001). These associations remained significant after adjusting for dietary fibre intake. We found even stronger associations between DHA and 38 operational taxonomic units (OTUs), the strongest ones being with OTUs from the Lachnospiraceae family (Beta(SE) = 0.13(0.03), P = 8 × 10−7). Some of the associations with gut bacterial OTUs appear to be mediated by the abundance of the faecal metabolite N-carbamylglutamate. Our data indicate a link between omega-3 circulating levels/intake and microbiome composition independent of dietary fibre intake, particularly with bacteria of the Lachnospiraceae family. These data suggest the potential use of omega-3 supplementation to improve the microbiome composition.

Introduction

There is evidence indicating that dietary supplementation with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) may improves some health parameters in humans1. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is an omega-3 fatty acid that is a main structural component of the human brain, cerebral cortex, skin, sperm, testicles and retina2. Higher circulating levels of DHA are associated with lower risk of future cardiovascular events in three prospective population based cohorts3. The other main omega-3 fatty acid is eicosapentaenoic acid or EPA, and omega-3 levels in humans are estimated by the sum of EPA + DHA with docosapentaenoic acid (DPA) being present at much lower concentrations4. Positive effects on health from omega-3 fatty acids have been observed for insulin resistance, adult-onset diabetes mellitus5–7, hypertension8, 9 arthritis10, 11, atherosclerosis12, 13, depression14, 15, thrombosis16, some cancers17 and cognitive decline18, 19.

These fatty acids can only be synthesized in mammals from the dietary precursor and essential fatty acid, α-linolenic acid1. However, the synthesis pathway requires a number of elongation and desaturation steps, making direct uptake from the diet a more effective route of assimilation. EPA and DHA in the human diet are derived primarily from marine algae (higher plants lack the enzymes for the biosynthesis of these lipids), which is concentrated in the flesh of marine fish where bioavailability is dramatically increased20. Some of the mechanisms whereby omega-3 fatty acids operate are linked directly to their anti-inflammatory actions since both EPA and DHA decrease synthesis of the pro-inflammatory prostaglandin E221. EPA and DHA are also precursors of the E-resolvins and D-resolvins that suppress inflammatory cytokine production and act to resolve inflammation22.

There is some evidence from case reports and from animal studies suggesting that the effect of omega-3 on the gut microbiota may also play an important role in the effects of omega-3 polyunsaturated acids on clinical parameters23–25. The relationship between the gut microbiota and its host plays a key role in immune system maturation, food digestion, drug metabolism, detoxification, vitamin production, and prevention of pathogenic bacteria adhesion. In fact, the composition of the microbiota is influenced by environmental factors such as diet, antibiotic therapy, and environmental exposure to microorganisms26.

Prebiotic foods are, by definition, non-digestible foods that specifically support the growth and/or activity of health-promoting bacteria that colonize the gastrointestinal tract. On the other hand, the role of omega-3 on microbiome composition and diversity has yet to be explored in human cohorts. Supplementation with DHA has been shown to help with oral and gastrointestinal diseases in which inflammation and bacterial dysbiosis play key roles27. Chronic low grade inflammation is often the result of an increase in plasma endotoxins, particularly lipopolysaccharides (LPS) derived from gut dysbiosis. The increase in plasma endotoxins leads to subsequent activation of the inflammasome and increased expression of inflammatory cytokines24. Analysis of gut microbiota and faecal transfer in mice has revealed that elevated tissue omega-3 fatty acids enhance intestinal production and secretion of intestinal alkaline phosphatase, which induces changes in the gut bacteria composition resulting in decreased lipopolysaccharide production and gut permeability, and ultimately, reduced metabolic endotoxemia and inflammation24.

A recent randomized, controlled clinical trial in an Indian population has shown that supplementation with omega 3 plus a probiotic has a greater beneficial effect on insulin sensitivity, lipid profile, and atherogenic index than the probiotic alone, although omega-3 supplementation showed only marginal effects on all the parameters28. A high omega-3 diet has also been shown to alter altered gut microbiota composition of drug-naïve patients with type 2 diabetes29. Such reports suggest an interaction between microbiome composition and intake of omega-3 fatty acids but a close examination of the links between omega-3 circulating levels and detailed microbiome composition in non-infant cohorts has not been explored to date.

Bacterial species, including those forming the human gut microbiome, are not well defined, and bacterial genomes are highly variable. Therefore regions used to identify bacteria vary in a continuum rather than clusters of similar sequences30. Bacteria that have 97% identity in a 16S rRNA gene variable region are considered to be the same taxa31. This is an arbitrary cut-off is thought to maximizes the grouping of bacteria classified as the same species while minimizing the grouping of bacteria classified as different species32. In order to determine how a batch of sequences should be partitioned into groups of 97% identity a clustering algorithm partitions the groups is used and taxonomic identity by matching the seed or central sequences with public databases are later assigned, the public database used was Greengenes in our case33. The resulting taxonomic groupings are known as Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs), and are used consistently within the same experiment.

The aim of this study is to assess the association between omega-3 fatty acids serum levels and intake with microbiome composition diversity and with specific OTUs.

Results

We analysed data from 876 female twins with 16 s microbiome data and circulating levels of fatty acids including DHA, total omega-3 fatty acids (FAW3), 18:2 linolenic acid (LNA), total omega-6 fatty acids (FAW6), total PUFA, and for comparison we also tested monounsaturated fatty acids; 16:1, 18:1 (MUFA), total saturated fatty acids (SFA), and total fatty acids (TotFA) measured at the same time point using the Brainshake NMR platform. Paired end reads covering the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene were merged with a minimum overlap of 200nt using default parameters in the QIIME join_paired_ends.py script. Demultiplexed reads were then subject to chimera detection and removal on a per sample basis using de novo chimera detection in USEARCH, after which 290445606 reads were retained from a total of 317617494 reads across all TwinsUK samples. Samples with less than 10,000 reads were discarded. Within the subset of 1044 samples used in the present study the final read depth was 80865 ± 35718 (mean ± SD). 1044 samples used in the present study the final read depth was 80865 ± 35718 (mean ± SD).

The demographic characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the 876 female twins studied, mean(SD).

| mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| age, yrs | 64.98 | 7.57 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.35 | 4.83 |

| Diversity measures | ||

| Shannon diversity | 6.42 | 0.79 |

| CHAO1 | 1976.97 | 667.21 |

| Observed Species | 876.52 | 255.98 |

| Phylogenetic Diversity | 67.99 | 19.15 |

| Simpson diversity | 0.95 | 0.04 |

| Serum Fatty Acids | ||

| DHA, mmol/l | 0.14 | 0.05 |

| FAW3, mmol/l | 0.44 | 0.14 |

| LNA, mmol/l | 3.0 | 0.59 |

| FAW6, mmol/l | 3.58 | 0.64 |

| PUFA, mmol/l | 4.02 | 0.75 |

| MUFA, mmol/l | 2.63 | 0.62 |

| SFA, mmol/l | 3.42 | 0.69 |

| TotFa, mmol/l | 10.08 | 1.94 |

| Dietary intake | ||

| Fibre dietary intake, g/day | 19.99 | 7.08 |

| DHA dietary intake, g/day | 0.35 | 0.86 |

| EPA dietary intake, g/day | 0.09 | 0.07 |

DHA docosahexaenoic acid, FAW3 total omega-3, LNA the omega-6 linoleic acid 18:2, FAW6 total omega 6 fatty acids, PUFA total polyunsaturated fatty acids, MUFA monounsaturated fatty acids; 16:1, 18:1, SFA saturated fatty acids, TotFA total fatty acids.

The serum circulating levels of the polyunsaturated fatty acids FAW3, FAW6, LNA, and DHA reflect in part the intake levels: we observe a significant correlation between dietary omega-3 fatty acid intake estimates from FFQs and serum levels of FAW3 (ρ = 0.168, p < 2.64 × 10−7).

Omega-3 and omega-6 associate with microbiome diversity

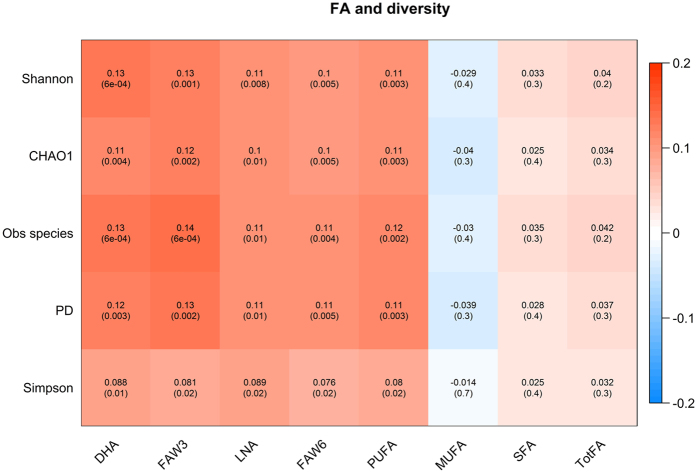

After adjusting for age and BMI, we find that circulating PUFA levels measured as DHA, FAW3, LNA, FAW6, total PUFA are significantly and consistently associated with higher microbiome diversity across the 5 alpha diversity indexes that we computed: Shannon, Chao1, Simpson and phylogenetic diversity indices, as well as observed species (e.g., with Shannon’s diversity DHA: Beta(SE) = 0.13(0.04), P = 0.0006; FAW3: 0.13(0.04), P = 0.0011, LNA: 0.11(0.004), P = 0.008, FAW6: 0.10(0.04), P = 0.0047, total PUFA: 0.11(0.04), P = 0.003). The complete results are presented in Fig. 1. We found however no significant association between microbiome diversity and circulating levels of saturated fatty acids or monounsaturated fatty acids (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Each cell of the matrix contains the correlation between one serum fatty acid and a gut microbiome diversity measure and the corresponding p value. Analyses are adjusted for age, BMI and family relatedness. The table is color coded by correlation according to the table legend (red for positive and blue for negative correlations). DHA docosahexaenoic acid, FAW3 total omega-3, LNA the omega-6 linoleic acid 18:2,FAW6 total omega 6 fatty acids, PUFA total polyunsaturated fatty acids, MUFA monounsaturated fatty acids; 16:1, 18:1, SFA saturated fatty acids, TotFA total fatty acids.

The association between FAW6 and microbiome diversity became not significant when adjusted for either FAW3 or only DHA (Beta(SE) = 0.035(0.04), P = 0.39). Similarly after adjustment for FAW6, FAW3 (i.e. DHA + EPA) became not significant (Beta 0.070 (0.04), P = 0.09). On the other hand the association between microbiome alpha diversity and DHA only (excluding other omega-3 fatty acids) remained statistically significant adjusting for FAW6 levels (Beta 0.080 (0.036), P = 0.03). Therefore we decided to focus specifically on DHA levels. We tested for association between dietary intake of DHA and microbiome diversity and found a weaker association between DHA intake and microbiome diversity (Beta(SE) = 0.06(0.03), P = 0.0203). As dietary fibre intake positively correlates with the gut microbiome34, we also ran the analysis adjusting for fibre intake and the results remained consistent (Supplementary Table 2).

In our data we calculated an estimate of microbial beta-diversity using both weighted and unweighted UniFrac distances30 as implemented in QIIME35 and used principal coordinate analysis to examine its associations with omega-3 circulating levels, but did not find significant patterns [data not shown]. This is expected as DHA is not the main source of microbiome variation, rather it is only one of the many variables influencing it. However, the significant correlations of DHA and FAW3, respectively, with microbial alpha diversity do demonstrate an association of these metabolites with the overall microbiome composition. DHA serum levels associate with OTU abundances

We then investigated the association between OTUs and DHA and identified 38 OTUs significantly associated with serum levels of DHA after adjusting for covariates and multiple testing using FDR < 0.05 (Table 2). Out of 36 positive associations, 21 (58%) belong to the Lachnospiraceaes, 7 (19%) to the Ruminococcacae and 5 (14%) to the Bacteroidetes. Because some of these associations may simply reflect a correlation with microbiome diversity we further adjusted for Shannon’s index. We found that after adjustment for microbiome diversity the significant associations with individual OTUs (using a cut-off of FDR p < 0.05) remain nominally statistically significant. Therefore the associations with individual OTUs are not due exclusively to the correlation between Lachnospiraceaes abundance and measures of gut microbiome diversity.

Table 2.

Associations between gut bacterial operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and serum levels of docosahexanoic acid (DHA).

| Internal** | OTU* | BETA | SE | P | Q |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| otu1501 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | 0.13 | 0.03 | 8.33 × 10−7 | 0.001 |

| otu1453 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | 0.13 | 0.03 | 9.11 × 10−7 | 0.001 |

| otu1367 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__Lachnospira; s__ | 0.13 | 0.03 | 3.36 × 10−6 | 0.002 |

| otu283 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__; g__; s__ | 0.10 | 0.02 | 2.61 × 10−5 | 0.009 |

| otu1554 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae | 0.11 | 0.03 | 6.72 × 10−5 | 0.019 |

| otu781 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__Lachnospira; s__ | 0.12 | 0.03 | 7.29 × 10−5 | 0.017 |

| otu1355 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | 0.11 | 0.03 | 7.76 × 10−5 | 0.016 |

| otu845 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__; g__; s__ | 0.11 | 0.03 | 1.04 × 10−4 | 0.019 |

| otu2057 | k__Bacteria; p__Bacteroidetes; c__Bacteroidia; o__Bacteroidales; f__Bacteroidaceae; g__Bacteroides; s__ | 0.11 | 0.03 | 1.30 × 10−4 | 0.021 |

| otu1793 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Erysipelotrichi; o__Erysipelotrichales; f__Erysipelotrichaceae; g__; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 1.44 × 10−4 | 0.021 |

| otu573 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | 0.11 | 0.03 | 1.85 × 10−4 | 0.024 |

| otu499 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__Coprococcus; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 1.99 × 10−4 | 0.024 |

| otu1933 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Ruminococcaceae; g__Oscillospira; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 2.32 × 10−4 | 0.026 |

| otu1760 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 2.59 × 10−4 | 0.027 |

| otu134 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Ruminococcaceae; g__; s__ | 0.11 | 0.03 | 3.01 × 10−4 | 0.029 |

| otu1061 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | 0.09 | 0.03 | 3.20 × 10−4 | 0.029 |

| otu1103 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 3.27 × 10−4 | 0.028 |

| otu1212 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Ruminococcaceae; g__Oscillospira; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 3.69 × 10−4 | 0.030 |

| otu867 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Ruminococcaceae; g__; s__ | 0.11 | 0.03 | 3.83 × 10−4 | 0.029 |

| otu1886 | k__Bacteria; p__Bacteroidetes; c__Bacteroidia; o__Bacteroidales; f__Bacteroidaceae; g__Bacteroides; s__uniformis | 0.09 | 0.03 | 3.85 × 10−4 | 0.028 |

| otu769 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Ruminococcaceae; g__; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 4.21 × 10−4 | 0.029 |

| otu1739 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae | 0.10 | 0.03 | 4.36 × 10−4 | 0.029 |

| otu1074 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Ruminococcaceae; g__Oscillospira; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 4.37 × 10−4 | 0.027 |

| otu169 | k__Bacteria; p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Enterobacteriales; f__Enterobacteriaceae | −0.09 | 0.03 | 5.80 × 10−4 | 0.035 |

| otu533 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 6.56 × 10−4 | 0.038 |

| otu271 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__Lachnospira; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 6.58 × 10−4 | 0.036 |

| otu2051 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 6.66 × 10−4 | 0.035 |

| otu1672 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__Lachnospira; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 6.73 × 10−4 | 0.035 |

| otu2050 | k__Bacteria; p__Bacteroidetes; c__Bacteroidia; o__Bacteroidales; f__Bacteroidaceae; g__Bacteroides; s__ | 0.09 | 0.03 | 7.84 × 10−4 | 0.039 |

| otu436 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 9.21 × 10−4 | 0.044 |

| otu1748 | k__Bacteria; p__Bacteroidetes; c__Bacteroidia; o__Bacteroidales; f__Bacteroidaceae; g__Bacteroides; s__ | 0.09 | 0.03 | 9.22 × 10−4 | 0.043 |

| otu2002 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | 0.09 | 0.03 | 9.94 × 10−4 | 0.045 |

| otu205 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__Lachnospira; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 9.99 × 10−4 | 0.044 |

| otu1063 | k__Bacteria; p__Proteobacteria; c__Gammaproteobacteria; o__Enterobacteriales; f__Enterobacteriaceae; g__; s__ | −0.09 | 0.03 | 1.06 × 10−3 | 0.045 |

| otu55 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__Roseburia; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 1.06 × 10−3 | 0.044 |

| otu662 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 1.10 × 10−3 | 0.044 |

| otu1621 | k__Bacteria; p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Ruminococcaceae; g__; s__ | 0.10 | 0.03 | 1.15 × 10−3 | 0.045 |

| otu2006 | k__Bacteria; p__Bacteroidetes; c__Bacteroidia; o__Bacteroidales; f__Bacteroidaceae; g__Bacteroides; s__uniformis | 0.09 | 0.03 | 1.29 × 10−3 | 0.049 |

Associations are expressed as the regression coefficient and standard error (adjusted for age, body mass index, family relatedness). P-values and FDR (Q-values) are shown. *OTUs are only analytical units which could represent individual strains or species, as such more than one can be assigned to the same taxonomy. **The internal name is meaningless and just randomly generated but it is there to indicate that there are separate hits.

We also explored whether the effects of percent DHA differed from those of absolute concentrations. We find that the same associations hold when absolute concentrations of DHA and percentage of DHA of all other fatty acids are seen both with regards to microbiome diversity (Shannon index association DHA% Shannon: Beta 0.15(0.04), P = 0.001 DHA absolute concentration 0.13(0.04), P = 0.001) and with regards to the most highly associated OTU (otu1505 association DHA% Shannon: Beta 0.11(0 .03), P = 3.0 × 10−5 vs DHA absolute concentration Beta 0.13(SE 0.03) P = 8.33 × 10−7).

Faecal metabolites associated with DHA levels and OTU abundances

To further understand the link between DHA levels and the gut microbiome we assessed the correlation between DHA circulating levels and faecal metabolites measured using commercial metabolomic panel (Metabolon Inc, Supplementary Table 3) in a subset of 707 individuals with data available. After adjusting for multiple testing using FDR < 0.05, the faecal metabolites associated with DHA serum levels were faecal levels of the omega-3 fatty acids EPA (Beta(SE) = 0.15(0.037), P = 4.35 × 10−5, FDR = 0.01), N-carbamylglutamate (0.15(0.039), P = 1.21 × 10−4, FDR = 0.02) and the dipeptide anserine (0.13(0.036), P = 5.3 × 10−4, FDR = 0.04) commonly found in fish and poultry meat36 and hence is likely to be positively correlated with fish intake) (Supplementary Table 1). We hypothesized that the association between some of the OTUs and DHA may be mediated by the levels in the gut of N-carbamylglutamate (NCG). We found that several OTUs whose abundance is associated with DHA serum levels are also associated with NCG faecal levels (Table 3). The association remains significant after adjustment for DHA, however some of the DHA associations with these OTUs are attenuated when adjusting for NCG levels (Table 3) suggesting that the correlation between the abundances some of these OTUs and DHA serum levels could be mediated by NCG faecal concentrations.

Table 3.

Association between gut bacterial operational taxonomic units (OTUs) and N-carbamylglutamate (NCG) in faeces unadjusted (unadj) and adjusting for DHA serum levels (adj).

| Internal | OTU | BETA | NCG | P | BETA | DHA | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SE | SE | |||||||

| otu1621 | p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Ruminococcaceae; g__; s__ | Unadj | 0.15 | 0.04 | 9.71 × 10−4 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.001 |

| Adj | 0.14 | 0.05 | 2.81 × 10−3 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.02 | ||

| otu573 | p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | Unadj | 0.13 | 0.04 | 1.15 × 10−3 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 1.85 × 10−4 |

| Adj | 0.12 | 0.04 | 3.79 × 10−3 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | ||

| otu769 | p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Ruminococcaceae; g__; s__ | Unadj | 0.12 | 0.04 | 2.92 × 10 −3 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 4.21 × 10 −4 |

| Adj | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | ||

| otu1793 | p__Firmicutes; c__Erysipelotrichi; o__Erysipelotrichales; f__Erysipelotrichaceae; g__; s__ | Unadj | 0.11 | 0.04 | 8.89 × 10−3 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 1.44 × 10−4 |

| Adj | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 1.44 × 10−4 | ||

| otu436 | p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | Unadj | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.012 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 9.21 × 10−4 |

| Adj | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.02 | ||

| otu2050 | p__Bacteroidetes; c__Bacteroidia; o__Bacteroidales; f__Bacteroidaceae; g__Bacteroides; s__ | Unadj | 0.1 | 0.04 | 0.013 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 7.84 × 10−4 |

| Adj | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 7.84 × 10−4 | ||

| otu1886 | p__Bacteroidetes; c__Bacteroidia; o__Bacteroidales; f__Bacteroidaceae; g__Bacteroides; s__uniformis | Unadj | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.015 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 3.85 × 10−4 |

| Adj | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||

| otu1453 | p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | Unadj | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.023 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 9.11 × 10 −7 |

| Adj | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.0008 | ||

| otu55 | p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__Roseburia; s__ | Unadj | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 1.06 × 10 −3 |

| Adj | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.02 | ||

| otu1061 | p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | Unadj | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 3.20 × 10−4 |

| Adj | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.01 | ||

| otu134 | p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Ruminococcaceae; g__; s__ | Unadj | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.032 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 3.01 × 10−4 |

| Adj | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0.001 | ||

| otu1074 | p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Ruminococcaceae; g__Oscillospira; s__ | Unadj | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.042 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 4.37 × 10−4 |

| Adj | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.04 | ||

| otu499 | p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__Coprococcus; s__ | Unadj | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.043 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 1.99 × 10 −4 |

| Adj | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.06 | ||

| otu1748 | p__Bacteroidetes; c__Bacteroidia; o__Bacteroidales; f__Bacteroidaceae; g__Bacteroides; s__ | Unadj | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.044 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 9.22 × 10−4 |

| Adj | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.1 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 0 | ||

| otu2051 | p__Firmicutes; c__Clostridia; o__Clostridiales; f__Lachnospiraceae; g__; s__ | Unadj | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.046 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 6.66 × 10 −4 |

| Adj | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

The association of the same OTUs with DHA adjusted and unadjusted for NCG is also shown. All analyses are adjusted for age, BMI, and family relatedness.

Discussion

In this study we show in a population based cohort of middle aged and elderly women that circulating levels of omega-3 fatty acids are associated with higher microbiome diversity and with a higher abundance of OTUs belonging to the Lachnospiraceae family.

Omega-3 levels in humans are determined by dietary intake and by conversion of alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) to DHA. Although it is possible that the gut microbiome affects absorption of these fatty acids, given that most of the absorption of fatty acids takes place in the small intestine, it seems more likely that the link that we observed between DHA and microbiome is mediated by circulating DHA, or by DHA incorporated into the large intestines or by other intermediates that DHA affects (e.g. D-series resolvins).

Having tested five different ecological measures of microbiome diversity we find that all of them are positively correlated with higher serum levels of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids and all of them show the same pattern with regards to the various fatty acid measures tested. Higher gut microbiome diversity is linked to lower inflammation37, 38, thus our data reinforce the notion that omega-3 fatty acids are linked to lower gut inflammation.

We also identified 38 OTUs associated with circulating levels of DHA. In particular we find that positive associations were enriched for the Lachnospiraceae family. Lachnospiraceae are one of the main taxonomic groups of the human gut where they function to degrade complex polysaccharides to short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as acetate, butyrate, and propionate that are used by the host for energy39. SCFAs are the end products of fermentation of dietary fibres by the anaerobic intestinal microbiota and have been shown to exert multiple beneficial effects on mammalian energy metabolism. The mechanisms underlying these effects encompass the complex interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism40. Members of the Lachnospiraceae family are found in higher abundance in herbivorous animals41. The wide range of functions carried out by Lachnospiraceae may influence their relative abundance in gut communities of different hosts. In humans, members of this family have been associated with protection against C. difficile infections42 and obesity43. They are also known as potent short-chain fatty acid producers44, On the other hand, we also find members of the Ruminococcaceae associated with increased levels of DHA and subtypes of some of this family have been implicated in obesity45.

The anti-inflammatory benefits of omega-3 PUFAs on gut microbiome composition may be attributed to the products of DHA metabolism, in particular those resulting from endogenous lipoxygenase-catalyzed hydroxylation of DHA, which in turn produces resolvins and protectin D1 through acetylation of the cyclooxygenase-2 enzyme46. Numerous reports describe protective effects of EPA- and DHA-derived mediators in experimental models of inflammatory bowel diseases47, 48 (reviewed in ref. 49). There is also some evidence of some benefit from supplementation of omega-3 fatty acids in humans affected by inflammatory bowel conditions50–52.

Modulation of these inflammatory pathways may similarly explain how DHA could reduce bowel inflammatory levels in bowel conditions where the ability of epithelial and immune cells in the intestine to differentiate between pathogenic and commensal bacteria leads to prolonged activation of nuclear factor-κB27. NF κB is a pro-inflammatory transcription factor which triggers overproduction of inflammatory cytokines. Inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract in turn interrupts the natural balance between the mucosal immune system and normal gut microbiota53. Although our data indicate that the DHA effect is independent of fibre intake, it is well known that SCFAs result from microbial fermentation of fibre40. Interventional nutritional studies may be required to quantify and dissect the contribution of these two types of dietary components on microbiome composition and SCFA production.

Moreover, most of the bacterial grouping that we find associated with increased levels of serum DHA are also negatively correlated with Crohn’s disease severity and intestinal inflammation (the Pediatric Crohn’s Disease Activity Index) such as Lachnospiraceae, Coprococcus, Roseburia, Ruminococcus, and Clostridium 54. These bacteria are known to be major producers of the SCFA butyrate55, 56.

In addition, we report that DHA serum levels correlate with the faecal concentration of NCG after adjusting for multiple testing. This carbamylated aminoacid, is available as a synthetic compound, but may also be generated in nature by protein carbamylation57. Given that the other faecal compounds strongly associated with DHA serum levels are omega-3 faecal levels and a dipeptide considered as a marker of animal protein (such as fish) intake, the abundance of this compound in the faeces is unlikely to be the result of intake of a supplement containing it. NCG is a precursor of arginine, a structural analogue of N- acetylglutamate and selective activator of the first enzyme of the urea cycle58. In animal studies NCG supplementation has been shown to improve arginine synthesis in enterocytes59, to regulate signalling pathways (such as signal transduction and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3), protein kinase B (PKB), and 70-kDa ribosomal protein S6 kinase)59 and to enhance intestinal growth as well as heat shock protein-70 expression60. Importantly, it also reduces oxidative stress in the gut61, 62 and alters intestinal gene expression63. Some of the NCG effects may be mediated via arginine which helps maintain intestinal homeostasis, preserves the integrity of the intestinal epithelium under stress, and prevents intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation64, 65.

Given the beneficial effects of NCG in the mammalian gut, part of the explanation for the association between DHA and gut microbiome composition might be that the presence of DHA favours the production of NCG by the gut microbiota. This in turn is likely to result in improved gut function and reduced oxidative stress. We see that the association between DHA circulating levels and some of the OTUs (such as Coprococcus, Oscillospira, Roseburia) is attenuated when we adjusted for NCG faecal levels (Table 3) suggesting that some of the DHA effect may be mediated by NCG. These are some of the bacteria that, as mentioned above, have been linked to either reduced intestinal inflammation or reduced risk of Crohn’s disease and are butyrate producers.

Although these results are only observational and cross-sectional they raise the possibility that omega-3 fatty acids may represent an important dietary supplement also to improve gut microbiome health. Our data suggest that the effect of omega-3 FA, in particular DHA, is independent of fibre intake. These data also support the hypothesis that some of the reported beneficial effects of omega-3 supplementation may be due to their effect on the gut microbiome. Nonetheless, intake of omega-3 fatty acids tends to correlate with a healthier lifestyle in general1 and therefore some of the effects of DHA on the gut may be indirect. This cannot be directly established in our study given the cross-sectional nature of the data analysed.

We note several study limitations. First, given the cross-sectional nature of the data, we cannot establish whether it is omega-3 affecting microbiome diversity or the other way round. On the other hand, it is well known that omega-3 circulating levels are reflective of dietary intake66 and although the associations we find with estimates of omega-3 dietary intake are weaker than with serum levels, this is likely to simply reflect the error of accurate estimates of intake from food questionnaire data compared to the accuracy of serum level measurements. Therefore, we hypothesize that it is intake of PUFAs and in particular of DHA that results in higher microbiome diversity and increased Lachnospiraceaes abundance. Our data are consistent with a recent randomized crossover clinical study in obese individuals where the effects of the gut microbiome were compared between supplementation with high oleic acid canola oil, and canola oil plus DHA. A principal analysis component carried by the authors revealed a strong enrichment of Lachnospiraceae in the canola plus DHA vs canola oil group, and more modest enrichments for Coprococcus and Ruminococcaceae 67. Second, our study also lacked direct measurement of SCFAs in order to show a direct correlation between DHA serum levels and SCFAs in the gut. Third, our cohort sonsists exclusively of middle aged and elderly women of European descent. The lack of male participants in our in this study limits the generalisability of our results since gender differences in the gut microbiome have been reported in humans68. Moreover, estrogens cause higher DHA concentrations in women than in men, probably by upregulating synthesis of DHA from alpha linoleic acid69. Additional studies including men may show stronger or weaker associations with omega-3 fatty acids. Fourth, we have used FFQs rather than other methods for assessing nutrient intake. It has been argued that 7-day diet diaries or records add useful information above and beyond FFQ remains and have higher reproducibility and lower error rates70. However,, the value of FFQs for assessing dietary composition has been documented objectively by correlations with biochemical indicators and the prediction of outcomes in prospective studies71. Moreover, the key results we report are with serum levels of DHA, which are highly correlated with intake figures estimated from FFQs.

We also note several study strengths. Our study has the largest sample size studied to date with regards to the relationship between omega-3 fatty acids and the gut microbiome composition. The study was able to compare various NMR measures of omega-3, omega-6 in addition to dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids. The study is one of the very few to investigate the link between microbiome associations and the faecal metabolome.

In conclusion, our data indicate a strong correlation between omega-3 fatty acids and microbiome composition and suggest that supplementation with PUFAs may be considered along with prebiotic and probiotic supplementation aimed at improving the microbiome composition and diversity. The study also suggests the translational potential NCG as a supplement to improve gut function and microbiome composition.

Methods

Study population

Study subjects were female twins enrolled in the TwinsUK registry, a national register of adult twins recruited as volunteers without selecting for any particular disease or trait traits72. In this study, we analysed data from 876 female twins with 16 s microbiome data and serum DHA, total omega-3, omega-6 and LA acids measured at the same time using the Brainshake NMR platform. The study was approved by NRES Committee London–Westminster, all experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and all twins provided informed written consent.

NMR Metabolomics

circulating levels of DHA, FWA3, LNA, FAW6, total PUFA, total MUFA, total SFA, and TotFA) were measured by Brainshake Ltd, Finland, (https://www.brainshake.fi/) from fasting serum samples using 500 Mhz and 600 Mhz proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy as previously described73. Traits were log-transformed and then scaled to standard deviation units, as previously proposed by Würtz et al.3. For the metabolites containing zeroes, 1 was added to all values of that metabolite before log-transformation.

Fibre and fatty acid intake

A validated 131-item semi-quantitative Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) established for the EPIC (European Prospective Investigations into Cancer and Nutrition)-Norfolk study74 was used to assess dietary intake. Estimated intakes of essential fatty acids and fibre (in grams per day) were derived from the UK Nutrient Database75 and were adjusted for energy intake using the residual method prior to analysis71.

Microbiota analysis

The stool DNA extraction is detailed in Goodrich et al.76 of 100 mg were taken from the sample and used for extraction. There was no homogenisation prior to this step. Faecal samples were collected and the composition of the gut microbiome was determined by 16 S rRNA gene sequencing carried out as previously described77, 78. Briefly, the V4 region of the 16 S rRNA gene was amplified and sequenced on Illumina MiSeq. Reads were then summarised to OTUs using open reference clustering Greengenes v13_8 at 97% sequence similarity78. OTU counts were converted to log transformed relative abundances, with zero counts handled by the addition of an arbitrary value (10−6). The residuals of the OTU abundances were taken from linear models, accounting for technical covariates including sequencing depth, sequencing run, sequencing technician and sample collection method. These residuals were inverse normalised, to make them normally distributed, and used in downstream parametric analyses. This approach allows us to adjust for potential confounders using parametric methods and is justified by both the sample size available and the normal distribution of the transformed OTU abundances.

The OTU table was rarefied to a depth of 10 000 OTUs per sample and five measures of gut microbiome alpha diversity were computed: Shannon, Chao1, Simpson and phylogenetic diversity indices, as well as observed species. Alpha diversity indexes were standardised to have mean 0 and SD 1.

Faecal metabolomics

Metabolite concentrations were measured from 707 faecal samples by Metabolon Inc., Durham, US, using an untargeted LC/MS platform as previously describe79, 80. Here we analysed 424 metabolites of known chemical identity observed in at least 80% of all samples. Metabolites were scaled by run-day medians and inverse normalised as the metabolite concentrations were not normally distributed. We imputed the missing values using the minimum run day measures.

Statistical analysis

We assessed the association between circulating serum levels of DHA, FAW3, LNA, FAW6, total PUFA, total MUFA, total SFA, TotFA by using random intercept linear regression adjusting for age, BMI and family relatedness. Linear regression was also employed to investigate the association between OTUs and DHA adjusting for covariates and multiple testing using false discovery rate (FDR < 0.05). We then calculated the principal coordinates from both weighted and unweighted UniFrac distances, a measure of microbial beta-diversity81, as implemented in QIIME35 to further examine the associations between omega-3 circulating levels and microbiome composition.

Finally, we assessed the correlation between DHA circulating levels and faecal metabolites in a sub-analysis of 707 individuals using linear regression adjusting for age, BMI, family relatedness and multiple testing (FDR < 0.05). We then tested the associations between the significant faecal metabolites and the previously identified OTU adjusting also for DHA.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the FP7 project HEALS (Health and Environment-wide Associations based on Large population Surveys) Project No. 603946 of the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme and by the Medical Research Council Ancestry and Biological Informative Markers for Stratification of Hypertension grant (MR/M016560/1). The TwinsUK microbiota project was funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH) RO1 DK093595, DP2 OD007444. Twins UK receives funding from the Wellcome Trust European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013 to TwinsUK); the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Facility at Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and NIHR Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. CM is funded by the MRC AimHy (MR/M016560/1) project grant. A.M.V. is suppo rted by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre based at Nottingham University Hospitals and the University of Nottingham. HLI collaborated with KCL to produce the metabolomics data from Metabolon Inc. We thank Dr Julia K. Goodrich, Dr Ruth E. Ley and the Cornell technical team for generating the microbial data. We wish to express our appreciation to all study participants of the TwinsUK cohort.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: C.M., T.D.S.; A.M.V. Analyzed the data: C.M., A.M.V. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: J.Z., T.P., M.A.J., R.P.M., T.L., C.J.S. Wrote the manuscript: C.M., A.M.V. Revised the manuscript: J.Z., T.P., M.A.J., R.P.M., C.J.S., T.D.S.

Competing Interests

RPM is employee of Metabolon, Inc. TDS is co-founder of MapMygut Ltd. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-10382-2

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ortega JF, et al. Dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids and oleate enhances exercise training effects in patients with metabolic syndrome. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016;24:1704–1711. doi: 10.1002/oby.21552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Howe P, Buckley J. Metabolic health benefits of long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Military medicine. 2014;179:138–143. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wurtz P, et al. Metabolite profiling and cardiovascular event risk: a prospective study of 3 population-based cohorts. Circulation. 2015;131:774–785. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.013116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonaa KH, Bjerve KS, Nordoy A. Docosahexaenoic and eicosapentaenoic acids in plasma phospholipids are divergently associated with high density lipoprotein in humans. Arteriosclerosis and thrombosis: a journal of vascular biology. 1992;12:675–681. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.12.6.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliveira V, et al. Diets Containing alpha-Linolenic (omega3) or Oleic (omega9) Fatty Acids Rescues Obese Mice From Insulin Resistance. Endocrinology. 2015;156:4033–4046. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogawa S, et al. Eicosapentaenoic acid improves glycemic control in elderly bedridden patients with type 2 diabetes. The Tohoku journal of experimental medicine. 2013;231:63–74. doi: 10.1620/tjem.231.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muldoon MF, et al. Concurrent physical activity modifies the association between n3 long-chain fatty acids and cardiometabolic risk in midlife adults. The Journal of nutrition. 2013;143:1414–1420. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.174078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Casanova MA, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids supplementation improves endothelial function and arterial stiffness in hypertensive patients with hypertriglyceridemia and high cardiovascular risk. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension: JASH. 2017;11:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbosa MM, Melo AL, Damasceno NR. The benefits of omega-3 supplementation depend on adiponectin basal level and adiponectin increase after the supplementation: A randomized clinical trial. Nutrition. 2017;34:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajaei E, et al. The Effect of Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Patients With Active Rheumatoid Arthritis Receiving DMARDs Therapy: Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Global journal of health science. 2015;8:18–25. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v8n7p18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jiang J, et al. Effect of Marine-Derived n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Major Eicosanoids: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis from 18 Randomized Controlled Trials. PloS one. 2016;11:e0147351. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosca L, et al. Usefulness of Icosapent Ethyl (Eicosapentaenoic Acid Ethyl Ester) in Women to Lower Triglyceride Levels (Results from the MARINE and ANCHOR Trials) The American journal of cardiology. 2017;119:397–403. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2016.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kristensen S, et al. The effect of marine n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on cardiac autonomic and hemodynamic function in patients with psoriatic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lipids in health and disease. 2016;15:216. doi: 10.1186/s12944-016-0382-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnold LE, et al. Omega-3 Fatty Acid Plasma Levels Before and After Supplementation: Correlations with Mood and Clinical Outcomes in the Omega-3 and Therapy Studies. Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology. 2017;27:223–233. doi: 10.1089/cap.2016.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pompili M, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and suicide risk in mood disorders: A systematic review. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry. 2017;74:43–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reiner MF, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids predict recurrent venous thromboembolism or total mortality in elderly patients with acute venous thromboembolism. Journal of thrombosis and haemostasis: JTH. 2017;15:47–56. doi: 10.1111/jth.13553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin G, et al. omega-3 free fatty acids and all-trans retinoic acid synergistically induce growth inhibition of three subtypes of breast cancer cell lines. Scientific reports. 2017;7:2929. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03231-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bulaj G, et al. Incorporating Natural Products, Pharmaceutical Drugs, Self-Care and Digital/Mobile Health Technologies into Molecular-Behavioral Combination Therapies for Chronic Diseases. Current clinical pharmacology. 2016;11:128–145. doi: 10.2174/1574884711666160603012237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horrocks LA, Yeo YK. Health benefits of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) Pharmacological research. 1999;40:211–225. doi: 10.1006/phrs.1999.0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Magalhaes JP, Muller M, Rainger GE, Steegenga W. Fish oil supplements, longevity and aging. Aging. 2016;8:1578–1582. doi: 10.18632/aging.101021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calder PC. Omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes. Nutrients. 2010;2:355–374. doi: 10.3390/nu2030355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Serhan CN, Dalli J, Colas RA, Winkler JW, Chiang N. Protectins and maresins: New pro-resolving families of mediators in acute inflammation and resolution bioactive metabolome. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2015;1851:397–413. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noriega BS, Sanchez-Gonzalez MA, Salyakina D, Coffman J. Understanding the Impact of Omega-3 Rich Diet on the Gut Microbiota. Case reports in medicine. 2016;2016:3089303. doi: 10.1155/2016/3089303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaliannan K, Wang B, Li XY, Kim KJ, Kang JX. A host-microbiome interaction mediates the opposing effects of omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids on metabolic endotoxemia. Scientific reports. 2015;5:11276. doi: 10.1038/srep11276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu HN, et al. Effects of fish oil with a high content of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on mouse gut microbiota. Archives of medical research. 2014;45:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vernocchi P, Del Chierico F, Putignani L. Gut Microbiota Profiling: Metabolomics Based Approach to Unravel Compounds Affecting Human Health. Frontiers in microbiology. 2016;7:1144. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tabbaa M, Golubic M, Roizen MF, Bernstein AM. Docosahexaenoic acid, inflammation, and bacterial dysbiosis in relation to periodontal disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and the metabolic syndrome. Nutrients. 2013;5:3299–3310. doi: 10.3390/nu5083299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rajkumar H, et al. Effect of probiotic (VSL#3) and omega-3 on lipid profile, insulin sensitivity, inflammatory markers, and gut colonization in overweight adults: a randomized, controlled trial. Mediators of inflammation. 2014;2014:348959. doi: 10.1155/2014/348959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balfego M, et al. Effects of sardine-enriched diet on metabolic control, inflammation and gut microbiota in drug-naive patients with type 2 diabetes: a pilot randomized trial. Lipids in health and disease. 2016;15:78. doi: 10.1186/s12944-016-0245-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong RG, Wu JR, Gloor GB. Expanding the UniFrac Toolbox. PloS one. 2016;11:e0161196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ciccarelli FD, et al. Toward automatic reconstruction of a highly resolved tree of life. Science. 2006;311:1283–1287. doi: 10.1126/science.1123061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caporaso JG, et al. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108(Suppl 1):4516–4522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000080107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeSantis TZ, et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2006;72:5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menni, C. et al. Gut microbiome diversity and high fibre intake are related to lower long term weight gain. Int J Obes (Lond) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Caporaso JG, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheung, W. et al. A metabolomic study of biomarkers of meat and fish intake. The American journal of clinical nutrition, doi:10.3945/ajcn.116.146639 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Nowak P, et al. Gut microbiota diversity predicts immune status in HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2015;29:2409–2418. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Claesson MJ, et al. Gut microbiota composition correlates with diet and health in the elderly. Nature. 2012;488:178–184. doi: 10.1038/nature11319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biddle, A., Stewart, L., Blanchard, J. & Leschine, S. Untangling the genetic basis of fibrolytic specialization by Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae in diverse gut communities. Diversity5, doi:10.3390/d5030627 (2013).

- 40.den Besten G, et al. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. Journal of lipid research. 2013;54:2325–2340. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R036012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Furet JP, et al. Comparative assessment of human and farm animal faecal microbiota using real-time quantitative PCR. FEMS microbiology ecology. 2009;68:351–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petrof EO, et al. Stool substitute transplant therapy for the eradication of Clostridium difficile infection: ‘RePOOPulating’ the gut. Microbiome. 2013;1:3. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho I, et al. Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity. Nature. 2012;488:621–626. doi: 10.1038/nature11400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duncan SH, Barcenilla A, Stewart CS, Pryde SE, Flint HJ. Acetate utilization and butyryl coenzyme A (CoA):acetate-CoA transferase in butyrate-producing bacteria from the human large intestine. Applied and environmental microbiology. 2002;68:5186–5190. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.10.5186-5190.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kasai C, et al. Comparison of the gut microbiota composition between obese and non-obese individuals in a Japanese population, as analyzed by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism and next-generation sequencing. BMC gastroenterology. 2015;15:100. doi: 10.1186/s12876-015-0330-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Serhan CN, et al. Novel proresolving aspirin-triggered DHA pathway. Chemistry & biology. 2011;18:976–987. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Q, Yu JC, Kang WM, Zhu GJ. Effect of omega-3 fatty acid on gastrointestinal motility after abdominal operation in rats. Mediators of inflammation. 2011;2011:152137. doi: 10.1155/2011/152137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohtsuka Y, et al. omega-3 fatty acids attenuate mucosal inflammation in premature rat pups. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2011;46:489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwanke RC, Marcon R, Bento AF, Calixto JB. EPA- and DHA-derived resolvins’ actions in inflammatory bowel disease. European journal of pharmacology. 2016;785:156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith HE, et al. Multiple micronutrient supplementation transiently ameliorates environmental enteropathy in Malawian children aged 12-35 months in a randomized controlled clinical trial. The Journal of nutrition. 2014;144:2059–2065. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.201673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamamoto T, Shimoyama T, Kuriyama M. Dietary and enteral interventions for Crohn’s disease. Current opinion in biotechnology. 2017;44:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barbalho SM, Goulart Rde A, Quesada K, Bechara MD, de Carvalho Ade C. Inflammatory bowel disease: can omega-3 fatty acids really help? Annals of gastroenterology. 2016;29:37–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shores DR, Binion DG, Freeman BA, Baker PR. New insights into the role of fatty acids in the pathogenesis and resolution of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2192–2204. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mottawea W, et al. Altered intestinal microbiota-host mitochondria crosstalk in new onset Crohn’s disease. Nature communications. 2016;7:13419. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takahashi K, et al. Reduced Abundance of Butyrate-Producing Bacteria Species in the Fecal Microbial Community in Crohn’s Disease. Digestion. 2016;93:59–65. doi: 10.1159/000441768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crystal TH, House AS. Articulation rate and the duration of syllables and stress groups in connected speech. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1990;88:101–112. doi: 10.1121/1.399955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meigh L. CO2 carbamylation of proteins as a mechanism in physiology. Biochemical Society transactions. 2015;43:460–464. doi: 10.1042/BST20150026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chacher B, Liu H, Wang D, Liu J. Potential role of N-carbamoyl glutamate in biosynthesis of arginine and its significance in production of ruminant animals. Journal of animal science and biotechnology. 2013;4:16. doi: 10.1186/2049-1891-4-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zeng X, et al. N-carbamylglutamate enhances pregnancy outcome in rats through activation of the PI3K/PKB/mTOR signaling pathway. PloS one. 2012;7:e41192. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wu X, et al. Dietary supplementation with L-arginine or N-carbamylglutamate enhances intestinal growth and heat shock protein-70 expression in weanling pigs fed a corn- and soybean meal-based diet. Amino acids. 2010;39:831–839. doi: 10.1007/s00726-010-0538-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cao W, et al. Dietary arginine and N-carbamylglutamate supplementation enhances the antioxidant statuses of the liver and plasma against oxidative stress in rats. Food & function. 2016;7:2303–2311. doi: 10.1039/C5FO01194A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu G, et al. Changes in the metabolome of rats after exposure to arginine and N-carbamylglutamate in combination with diquat, a compound that causes oxidative stress, assessed by 1H NMR spectroscopy. Food & function. 2016;7:964–974. doi: 10.1039/C5FO01486G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wu X, Zhang Y, Liu Z, Li TJ, Yin YL. Effects of oral supplementation with glutamate or combination of glutamate and N-carbamylglutamate on intestinal mucosa morphology and epithelium cell proliferation in weanling piglets. Journal of animal science. 2012;90(Suppl 4):337–339. doi: 10.2527/jas.53752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Costa KA, et al. L-arginine supplementation prevents increases in intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation in male Swiss mice subjected to physical exercise under environmental heat stress. The Journal of nutrition. 2014;144:218–223. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.183186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fritz JH. Arginine cools the inflamed gut. Infection and immunity. 2013;81:3500–3502. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00789-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Baia LC, et al. Fish and omega-3 fatty acid intake in relation to circulating fibroblast growth factor 23 levels in renal transplant recipients. Nutrition, metabolism, and cardiovascular diseases: NMCD. 2014;24:1310–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pu S, Khazanehei H, Jones PJ, Khafipour E. Interactions between Obesity Status and Dietary Intake of Monounsaturated and Polyunsaturated Oils on Human Gut Microbiome Profiles in the Canola Oil Multicenter Intervention Trial (COMIT) Frontiers in microbiology. 2016;7:1612. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haro C, et al. Intestinal Microbiota Is Influenced by Gender and Body Mass Index. PloS one. 2016;11:e0154090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giltay EJ, Gooren LJ, Toorians AW, Katan MB, Zock PL. Docosahexaenoic acid concentrations are higher in women than in men because of estrogenic effects. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2004;80:1167–1174. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.5.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Day N, McKeown N, Wong M, Welch A, Bingham S. Epidemiological assessment of diet: a comparison of a 7-day diary with a food frequency questionnaire using urinary markers of nitrogen, potassium and sodium. International journal of epidemiology. 2001;30:309–317. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Willett W, Stampfer MJ. Total energy intake: implications for epidemiologic analyses. American journal of epidemiology. 1986;124:17–27. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moayyeri A, Hammond CJ, Valdes AM, Spector TD. Cohort Profile: TwinsUK and healthy ageing twin study. International journal of epidemiology. 2013;42:76–85. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Soininen P, Kangas AJ, Wurtz P, Suna T, Ala-Korpela M. Quantitative serum nuclear magnetic resonance metabolomics in cardiovascular epidemiology and genetics. Circulation. Cardiovascular genetics. 2015;8:192–206. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.000216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bingham SA, et al. Nutritional methods in the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer in Norfolk. Public health nutrition. 2001;4:847–858. doi: 10.1079/PHN2000102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.McCance, R. A., Widdowson, E. M., Holland, B., Welch, A. & Buss, D. H. McCance and Widdowson’s The Composition of Foods 5th edn, (Great Britain Food Standards Agency, 1991).

- 76.Goodrich JK, et al. Human genetics shape the gut microbiome. Cell. 2014;159:789–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goodrich JK, et al. Genetic Determinants of the Gut Microbiome in UK Twins. Cell host & microbe. 2016;19:731–743. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jackson MA, et al. Proton pump inhibitors alter the composition of the gut microbiota. Gut. 2016;65:749–756. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shin SY, et al. An atlas of genetic influences on human blood metabolites. Nature genetics. 2014;46:543–550. doi: 10.1038/ng.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Menni C, et al. Metabolomic markers reveal novel pathways of ageing and early development in human populations. International journal of epidemiology. 2013;42:1111–1119. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wood AR, et al. Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height. Nature genetics. 2014;46:1173–1186. doi: 10.1038/ng.3097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.