Abstract

Background

To identify and remediate gaps in the quality of surgical care, the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBrS) developed surgeon-specific quality measures (QMs), built a patient registry, and nominated itself to become a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Qualified Clinical Data Registry (QCDR), thereby linking surgical performance to potential reimbursement and public reporting. This report provides a summary of the program development.

Methods

Using a modified Delphi process, more than 100 measures of care quality were ranked. In compliance with CMS rules, selected QMs were specified with inclusion, exclusion, and exception criteria, then incorporated into an electronic patient registry. After surgeons entered QM data into the registry, the ASBrS provided real-time peer performance comparisons.

Results

After ranking, 9 of 144 measures of quality were chosen, submitted, and subsequently accepted by CMS as a QCDR in 2014. The measures selected were diagnosis of cancer by needle biopsy, surgical-site infection, mastectomy reoperation rate, and appropriateness of specimen imaging, intraoperative specimen orientation, sentinel node use, hereditary assessment, antibiotic choice, and antibiotic duration. More than 1 million patient-measure encounters were captured from 2010 to 2015. Benchmarking functionality with peer performance comparison was successful. In 2016, the ASBrS provided public transparency on its website for the 2015 performance reported by our surgeon participants.

Conclusions

In an effort to improve quality of care and to participate in CMS quality payment programs, the ASBrS defined QMs, tracked compliance, provided benchmarking, and reported breast-specific QMs to the public.

For more than two decades, strong evidence has indicated variation in the quality of cancer care in the United States.1–19 As a result, measurements and audits are necessary to search for gaps in the quality of care. Toward this end, multiple professional organizations have developed condition-specific quality measures (QMs) to assess the clinical performance surrounding the patient-provider encounter.

Quantification of performance can identify variation and opportunities for improvement. If performance assessment is followed by performance comparison among peers (i.e., benchmarking) coupled with transparency among providers, physicians who find themselves in the lower tiers of performance can be motivated to improve, ultimately yielding better overall care at the population level, a phenomenon that recently has been reviewed and demonstrated by several programs.20–26

This report aims to describe how the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBrS) ranked and defined measures of quality of care and subsequently provided benchmarking functionality for its members to compare their performances with each other. By separate investigations, the actual performance demonstrated by our ASBrS membership for compliance with nine breast surgeon-specific QMs are reported.

Founded in 1995, the ASBrS is a young organization. Yet, within 20 years, membership has grown to more than 3000 members from more than 50 countries. A decade ago, the Mastery of Breast Surgery Program (referred to as “Mastery” in this report) was created as a patient registry to collect quality measurement data for its members.27

Past President Eric Whitacre, who actually programmed Mastery’s original electronic patient registry with his son Thomas, understood that “quality measures, in their mature form, did not merely serve as a yardstick of performance, but were a mechanism to help improve quality.”28,29 Armed with this understanding, the ASBrS integrated benchmarking functionality into Mastery, thus aligning the organization with the contemporary principles of optimizing cancer care quality as described by policy stakeholders.2,19,25,30

In 2010, Mastery was accepted as a Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) Physicians Qualified Reporting Service (PQRS) and then as a Qualified Clinical Data Registry (QCDR) in 2014, linking provider performance to government reimbursement and public reporting.31 Surgeons who successfully participated in Mastery in 2016 will avoid the 2018 CMS “payment adjustment” (2% penalty), a further step toward incentivizing performance improvement in tangible ways.

Methods

Institutional Review Board

De-identified QM data were obtained with permission from the ASBrS for the years 2011–2015. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Gundersen Health System deemed the study was not human subjects’ research. The need for IRB approval was waived.

Choosing, Defining, and Vetting QM

From 2009 to 2016, the Patient Safety and Quality Committee (PSQC) of the ASBrS solicited QM domains from its members and reviewed those of other professional organizations.32–39 As a result, as early as 2010, a list of more than 100 domains of quality had been collected, covering all the categories of the Donabedian trilogy (structure, process, and outcomes) and the National Quality Strategy (safety, effectiveness, efficiency, population health, care communication/coordination, patient-centered experience).40,41 By 2013, a list of 144 measures underwent three rounds of modified Delphi process ranking by eight members of the PSQC, using a RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Methodology, which replicated an American College of Surgeons effort to rank melanoma measures and was consistent with the National Quality Forum’s guide to QM development42,43 (Tables 1, 2). During the ranking, quality domains were assigned a score of 1 (not valid) to 9 (valid), with a score of 5 denoting uncertain/equivocal validity. After each round of ranking, the results were discussed within the PSQC by email and phone conferences. At this time, arguments were presented for and against a QM and its rank. A QM was deemed valid if 90% of the rankings were in the range of seven to nine.

Table 1.

Instructions of the American Society of Breast Surgeons for ranking of quality measure domains

| Ranking 42,43 |

| 1. [Evaluate the quality domains] for appropriateness (median ranking) and agreement (dispersion of rankings) to generate quality indicators |

| 2. A measure [will be] considered valid if adherence with this measure is critical to provide quality care to patients with [breast cancer], regardless of cost or feasibility of implementation. Not providing the level of care addressed in the measure would be considered a breach in practice and an indication of unacceptable care |

| 3. Validity rankings are based on the panelists’ own personal judgments and not on what they thought other experts believed |

| 4. The measures should apply to the average patient who presents to the average physician at an average hospital |

| Importance criteria 57 |

| 1. Variation of care |

| 2. Feasibility of measurement, without undue burden |

| 3. Usability for accountability [public transparency or quality payment programs] |

| 4. Applicability for quality improvement activity |

| Scoring criteria 42,43 |

| 1 = not valid |

| 5 = uncertain/equivocal validity |

| 9 = valid |

Verbatim instructions from an American College of Surgeons ranking study43

Table 2.

Hierarchy of quality domains for breast surgeons after the 3rd round of modified Delphi ranking

| Quality domain | Median scorea | Validityb | Agreementc |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients receiving diagnosis of cancer by needle biopsy | 9 | Yes | Agreement |

| Patients undergoing a formal patient-side-site-procedure verification procedure in the operating room | 9 | No | Agreement |

| Percentage of cancer patients with orientation of lumpectomy specimen | 9 | Yes | Agreement |

| Clinical stages 1 and 2 node-negative patients offered sentinel lymph node (SLN) surgery | 9 | Yes | Agreement |

| Mastectomy patients with ≥4 positive nodes referred to radiation oncologist | 9 | Yes | Agreement |

| Stages 1, 2, and 3 patients undergoing initial breast cancer surgery with documentation of ER, PR receptor status | 9 | No | Agreement |

| Stage 1, 2, and 3 undergoing initial breast cancer surgery with documentation of HER2 neu status | 9 | No | Agreement |

| Breast conservation therapy (BCT) patients referred to radiation oncology | 9 | Yes | Agreement |

| Percentage of patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy before planned breast conservation surgery (BCS) who have imaging marker clip placed in breast | 9 | Yes | Agreement |

| Percentage of patients undergoing lumpectomy for non-palpable cancer with specimen imaging performed | 9 | Yes | Agreement |

| Patients with concordance assessment (testing) of Exam-Imaging-Path by care provider | 9 | No | Agreement |

| Patients undergoing breast cancer surgery with final path report indicating largest single tumor size | 8.5 | No | Agreement |

| Patient’s compliant with National Quality Forum Quality Measures (NQF QM) for endocrine therapy in hormonal receptor positive patients | 8.5 | Yes | Agreement |

| Trastuzumab is considered or administered within 4 months (120 days) after diagnosis for stage 1, 2, or 3 breast cancer that is HER2-positive | 8.5 | No | Agreement |

| Documentation of mastectomy patients offered referral to plastic surgery | 8.5 | Yes | Agreement |

| Documentation of eligibility of BCT and eligible patients offered BCT | 8.5 | Yes | Agreement |

| Patients with documentation of patient options for treatment regardless of procedure type | 8.5 | Yes | Agreement |

| Percentage of patients undergoing BCT with a final ink-negative margin, regardless of number of operations | 8.5 | No | Agreement |

| Patients with adequate history by care provider | 8 | No | Agreement |

| Patients with documentation of postoperative cancer staging (AJCC) | 8 | Yes | Agreement |

| Patient’s compliant with NQF QM for radiation after lumpectomy | 8 | No | Agreement |

| Patients with documentation preoperative (pretreatment) AJCC clinical staging | 8 | Yes | Agreement |

| NCCN compliance with radiation guidelines | 8 | No | Agreement |

| Mastectomy patients receiving preoperative antibiotics | 8 | Yes | Agreement |

| Patients with NCCN guideline compliant care for “high risk lesions” identified on needle biopsy (ADH, ALH, FEA, LCIS, papillary lesion, radial scar, mucin-containing lesion) | 8 | No | Agreement |

| Patients with NCCN guidelines compliant care for diagnostic evaluation of breast lump | 8 | No | Agreement |

| Patients with NCCN compliance for postoperative lab imaging, biomarkers in stages 0, 1, and 2 patients | 8 | No | Agreement |

| NCCN guideline compliance for genetic testing among patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer | 8 | No | Agreement |

| NCCN guideline compliance for genetics assessment/referral among patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer | 8 | No | Agreement |

| Patients with adequate examination by care provider | 7.5 | No | Agreement |

| Patients with final pathologic size ≥ stage 1 T1cN0M0 who have documentation of discussion regarding adjuvant treatment | 7.5 | Yes | Agreement |

| Documentation of reason why patient is not eligible for BCT | 7.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with adequate review of imagining by care provider | 7.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with inflammatory or locally advanced breast cancer who undergo neoadjuvant treatment before surgery | 7.5 | No | Agreement |

| High-risk patients with estimated lifetime risk >20% offered screening MRI | 7.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| NCCN compliance for medical oncology recommendations | 7.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Risk adjusted re-excision lumpectomy rate after breast-conserving therapy | 7.5 | Yes | Agreement |

| NCCN guideline compliance for inflammatory breast cancer | 7.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| NCCN guideline compliance for breast cancer in pregnancy | 7.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with predicted estimate of BRCA mutation >10% offered BRCA testing | 7.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| High-risk patients (no known cancer) with documentation of risk-reduction counseling | 7.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| NCCN guideline compliance for inadequate margins requiring re-excision in BCS patients | 7.5 | No | Agreement |

| Patients receiving antibiotics within 1 h before surgery | 7 | Yes | Agreement |

| Patients receiving a first- or second-generation cephalosporin before incision | 7 | Yes | Agreement |

| Patients with discontinuations of antibiotics within 24 h after surgery | 7 | Yes | Agreement |

| Patients with Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) antibiotic measure compliance (includes all 3 measures above) | 7 | Yes | Agreement |

| Patients with breast cancer with documentation of risk assessment for germline mutation | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients compliant with SCIP DVT/PE prophylaxis recommendations | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients ≤50 years with newly diagnosed breast cancer offered genetic testing | 7 | Yes | Agreement |

| Patients presented to interdisciplinary tumor board (real or virtual) at any time | 7 | No | Agreement |

| Patients compliant with NQF QM for chemotherapy in hormonal receptor-negative patients | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Surgical-site infection rate (mastectomy patients) | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of patients entered into a patient registry to identify patient complications and cancer outcomes | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| One-step surgery success rate stratified by type of operation (mastectomy) | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Sentinel lymph node identification rate (%) in breast cancer surgery | 7 | Yes | Agreement |

| Cosmetic score (measure of cosmesis) after BCS (patient self-assessment with Harvard score) | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Time (business days) from diagnostic evaluation to needle biopsy | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Time (business days) from needle biopsy path report to surgical appointment | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Surgical-site infection rate (mastectomy plus plastic surgery patients) | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence (IBTR) | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of patients undergoing lumpectomy for non-palpable cancer with two-view specimen imaging performed | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of compliance with ASBrS or ACR annotation of ultrasound (US) images | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of compliance with ASBrS or ACR recommendations for US reports | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of compliance with ASBrS or ACR recommendations for US needle biopsy reports | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Compliance with ASBrS or ACR recommendations for US needle biopsy reports | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| NCCN guideline compliance for pre-op lab and imaging in clinical stages 0, 1, and 2 patients with cancer | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with preoperative needle biopsy proven axillary node who do not undergo sentinel node procedure | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Local regional recurrence | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients age ≥70 years, hormone receptor positive, with invasive cancer offered endocrine therapy instead of radiation (documentation) | 7 | No | Indeterminant |

| Disease-free survival | 6.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Time business days from new breast cancer to office appointment | 6.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with predicted estimate of BRCA mutation >10% who are tested | 6.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Time business days from needle biopsy path report of cancer to surgical operation | 6.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Time business days from abnormal screening mammography to diagnostic evaluation | 6.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of cancer patients entered into a quality audit (any type: institutional, personal case log, regional, national) | 6.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Time business days from new breast symptom to office appointment | 6.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with benign breast disease with documentation of risk assessment for cancer | 6.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of patients with partial breast irradiation after lumpectomy who are compliant with “ASBrS guidelines for eligibility” | 6.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of patients with partial breast irradiation after lumpectomy who are compliant with “ASTRO guidelines for eligibility” | 6.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Number of breast-specific CMEs per year | 6.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| NCCN compliance for SLN surgery in stage 0 DCIS | 6.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Skin flap necrosis rate after mastectomy stratified by type of mastectomy reconstruction, type of reconstruction | 6.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Overall survival | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| Ratio of malignant-to-benign minimally invasive breast biopsies | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| Surgical-site infection rate (all patients) | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| Surgeon US (2 × 2 test table performance) (sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV) for surgeons performing diagnostic breast evaluation with imaging | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| NCCN guideline compliance for phyllodes tumor | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| Compliance with ASBrS or ACR recommendations for stereotactic biopsy reports | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| Time business days from surgeon appointment for cancer to surgery for cancer | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of mastectomy patients undergoing reconstruction | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| Cost of perioperative episode of care (affordability) | 6 | No | Agreement |

| Patients with cancer diagnosed for core needle biopsy (CNB) for BiRads 4a lesion | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with cancer diagnosed for CNB for BiRads 4b lesion | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with cancer diagnosed for CNB for BiRads 4c lesion | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with cancer diagnosed for CNB for BiRads 5 lesion | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| NCCN guideline compliance for Paget’s disease | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| Surgical-site infection rate (BCS patients) | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| Number of axillary nodes obtained in patients undergoing level 1 or 2 nodal surgery (median) | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of DCIS patients undergoing BCS for cancer who do not have axillary surgery | 6 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with College of American Pathologists (CAP) compliant reporting | 5.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Breast cancer patients presented to interdisciplinary tumor board (real or virtual) before 1st treatment | 5.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of cancer patients enrolled in clinical trials | 5.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Mastectomy patients with positive SLN who undergo completion of axillary dissection | 5.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with cancer diagnosed on CNB for BiRads 3 lesion | 5.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with unifocal cancer smaller than 3 cm who undergo BCT | 5.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with documentation of pre-op breast size and symmetry | 5.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Clinical stage 0 DCIS patients who do not undergo SLN surgery for BCT | 5.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients undergoing level 1 or 2 axillary dissection with ≥15 nodes removed | 5.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Number of SLN’s (median) in patients undergoing SLN procedure | 5.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Breast volume (number of cancer cases per year per surgeon) | 5.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of cancer patients with documentation of search for clinical trial | 5.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of breast biopsy pathology requisition forms containing adequate information for pathologist (history, CBE, imaging) | 5 | No | Agreement |

| Time from initial cancer surgery to pathology report | 5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with documentation of pre-op contralateral breast cancer risk | 5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Clinical stage 0 DCIS patients who do not undergo SLN surgery for mastectomy | 5 | No | Indeterminant |

| BCT rate (actual and potential) | 5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Time business days from abnormal screening mammogram (SM) to office appointment | 5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with documentation of needle biopsy results delivered to patients within 48 h | 5 | No | Indeterminant |

| BCT-eligible patients offered neoadjuvant treatment | 5 | No | Agreement |

| Interval cancers (cancer detected within 1 year after negative US biopsy or stereotactic biopsy) | 5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Cosmetic score (measure of cosmesis) after mastectomy, no reconstruction (patient self-assessment) | 5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of cancer patients referred to medical oncology | 5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Axillary recurrence rate | 5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with NCCN guidelines compliant care for nipple discharge | 5 | No | Disagreement |

| Percentage of BCT patients with marker clips placed in lumpectomy cavity to aid radiation oncologist for location of boost dose for radiation | 5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of patients with documentation of arm edema status post-operatively | 4.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients undergoing re-operation within 30 days (stratified by case type) | 4.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients undergoing re-admission within 30 days (stratified by base type) | 4.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of BCT patients with oncoplastic procedure performed | 4.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with documentation of gynecologic/sexual side effects of endocrine therapy | 4.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with documentation of gynecologic/sexual changes during follow-up | 4.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Mastectomy patients who undergo immediate intraoperative SLN assessment | 4.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with latragenic injury to adjacent organ, structure (stratified by case type) | 4 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of lumpectomy patients with surgeon use of US intraoperatively | 4 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with documentation of surgical pathology results delivered to patients within 96 h | 4 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients who have “grouped” postoperative appointments (same day, same location with care providers) | 4 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percutaneous procedure complications | 3.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Percentage of patients with development of lymphedema of arm after axillary surgery | 3.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Time from initial cancer surgery to pathology report | 3 | No | Disagreement |

| Patients with new DVT less than or equal to 30 days post-operatively | 3 | No | Disagreement |

| Patients with new PE ≤30 days post-operatively | 3 | No | Indeterminant |

| Documentation of use of new NSQIP-generated ACS risk calculator preoperatively | 3 | No | Indeterminant |

| Patients with unplanned overnight stay stratified by procedure type | 2.5 | No | Indeterminant |

| Sensitivity of immediate intraoperative detection of positive SLN (pathology quality measure) | 2.5 | No | Agreement |

| Patients with myocardial infarction ≤30 days postoperatively | 2 | No | Agreement |

| Patients with new renal failure ≤30 days postoperatively | 2 | No | Agreement |

| Patients with new respiratory failure ≤30 days post-operatively | 2 | No | Agreement |

ER estrogen receptor; PR progesterone receptor; HER2 human epidermal growth factor 2; AJCC American Joint Committee on Cancer; NCCN National Comprehensive Cancer Network; ADH Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia; ALH Atypical lobular hyperplasia; FEA Flat epithelial atypia; LCIS Lobular carcinoma in situ; MRI magnetic resonance imaging; SCIP Surgical care improvment project; DVT Deep venous thrombosis; PE Pulmonary embolism; ASBrS American Society of Breast Surgeons; ACR American College of Radiology; ASTRO American Society of therapuetic radiation oncologists; CME Continuing medical education credits; DCIS Ductal carcinoma in situ; PPV positive predictive value; NPV negative predictive value; CBE clinical breast exam; NSQIP National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; ACS American Cancer Society

aMedian score 1–9: lowest to highest

bValidity: ≥90% of the rankings are in the 7–9 range

cAgreement: Based on scoring dispersion (e.g., for a panel of 13, there is “agreement” if >8 rankings are in any 3-point range and disagreement if >3 rankings are 1–3 and 7–9

Italicized text: Final ASBrS QM chosen for CMS quality payment programs

After three rounds of ranking ending in December 2013, nine of the highest ranked measures were “specified” as described and required by CMS44 (Table 3). Briefly, exclusions to QM reporting were never included in the performance numerator or denominator. Exceptions were episodes in which performance for a given QM was not met but there was a justifiable reason why that was the case. If so, then the encounter, similar to an exclusion, was not included in the surgeon’s performance rate. If an encounter met performance criteria despite typically meeting exception criteria, the encounter was included in the performance rate. Per CMS rules, each QM was linked to a National Quality Strategy Aim and Domain (Table 3). The QMs also were assigned to a Donabedian category and to one or more of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s “triple aims.”40,45

Table 3.

American Society of Breast Surgeons Quality Measure Specifications for participation in the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services Qualified Clinical Data Registry55,56

| QM title | QM name | QM numerator | QM denominator | Exception examplesa | Exclusion examplesb | Measure typec | NQS domain(s)d | IHI triple aime |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Needle biopsy | PQRS measure #263: Preoperative diagnosis of breast cancer | No. of patients age ≥18 years undergoing breast cancer operations who had breast cancer diagnosed preoperatively by a minimally invasive biopsy | No. of patients age ≥18 years on date of encounter undergoing breast cancer operations | Lesion too close to implant Patient too obese for stereotactic table Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy Needle performed but identified “high risk” lesion only |

Not a breast procedure | Process | Effective clinical care Efficiency and cost reduction |

Care experience Per capita cost |

| Image confirmation | PQRS measure #262: Image confirmation of successful excision of image-localized breast lesion | Patient undergoing excisional biopsy or partial mastectomy of a nonpalpable lesion whose excised breast tissue was evaluated by imaging intraoperatively to confirm successful inclusion of targeted lesion | No. of patients age ≥18 years on date of encounter with nonpalpable, image-detected breast lesion requiring localization of lesion for targeted resection | Target lesion identified intraoperatively by pathology MRI wire localization for lesion occult on mammography and ultrasound |

Lesion palpable preoperatively Re-excision surgery for margins Ductal excision without visible lesion on imaging |

Process | Patient safety | Care experience |

| Sentinel node | PQRS measure #264: Sentinel lymph node biopsy for invasive breast cancer | Patients who undergo a sentinel lymph node biopsy procedure | Patients age ≥18 years with clinically node-negative stage 1 or 2 primary invasive breast cancer | Prior nodal surgery Recurrent cancer Limited life expectancy |

No preoperative invasive cancer diagnosis Patient has proven axillary metastasis Inflammatory breast cancer |

Process | Effective clinical care Safety |

Care experience Per capita cost |

| Hereditary assessment | ASBS 1: Surgeon assessment for hereditary cause of breast cancer | No. of breast cancer patients with newly diagnosed invasive and DCIS seen by surgeon who undergo risk assessment for a hereditary cause of breast cancer | No.of newly diagnosed invasive and DCIS breast cancer patients seen by surgeon and who undergo surgery | Patient was adopted Family history not obtainable for any specific reason |

LCIS patients Patient does not have breast cancer or patient does not undergo surgery |

Process | Effective clinical care Community and population health (e.g., screening for germline mutation in family members) |

Care experience Population health |

| Surgical-site infection | ASBS 2: Surgical-site infection and cellulitis after breast and/or axillary surgery | No. of patients age ≥18 years who experience an SSI or cellulitis within 30 days after undergoing a breast and/or an axillary operation | No. of patients age ≥18 years on date of encounter undergoing a breast and/or axillary operation | None | Patient did not undergo breast or axillary surgery | Outcome | Person and caregiver-centered experience and outcomes | Care experience Per capita cost |

| Specimen orientation | ASBS 3: Specimen orientation for partial mastectomy or excisional breast biopsy | No. of patients age ≥18 years undergoing a therapeutic breast surgical procedure considered an initial partial mastectomy or “lumpectomy” for a diagnosed cancer or an excisional biopsy for a lesion that is not clearly benign based on previous biopsy or clinical and radiographic criteria with surgical specimens properly oriented for pathologic analysis such that six margins can be identified | No. of patients age ≥18 years undergoing a therapeutic breast surgical procedure considered an initial partial mastectomy or “lumpectomy” for a diagnosis of cancer or an excisional biopsy for a lesion that is not clearly benign based on previous biopsy or clinical and radiographic criteria | Clinical and imaging findings suggest benign lesion (e.g., fibroadenoma) | Patients who had total mastectomy (all types) | Process | Communication and care coordination | Care experience |

| Antibiotic choice | ASBS 5: Perioperative care: Selection of prophylactic antibiotics: first- or second-generation cephalosporin (modified for breast from PQRS measure #21) | Surgical patients age ≥18 years undergoing procedures with indications for a first- or second- generation cephalosporin prophylactic antibiotic who had an order for a first- or second -generation cephalosporin for antimicrobial prophylaxis | All surgical patients age ≥18 years undergoing procedures with the indications for a first- or second -generation cephalosporin prophylactic antibiotic | Patient allergic to cephalosporins | Not a breast procedure | Process | Patient safety | Care experience Per capita cost |

| Antibiotic duration | ASBS 6: Perioperative care: Discontinuation of prophylactic parenteral antibiotics (modified for breast from PQRS measure #22) | Noncardiac surgical patients who have an order for discontinuation of prophylactic parenteral antibiotics within 24 h after surgical end time | All noncardiac surgical patients age ≥18 years undergoing procedures with the indications for prophylactic parenteral antibiotics and who received a prophylactic parenteral antibiotic | Antibiotic not discontinued: ordered by plastic surgeon for expander or implant insertion | Not a breast procedure | Process | Patient safety | Care experience Per capita cost |

| Mastectomy reoperation | Unplanned 30-day re-operation rate after mastectomy | Patients undergoing mastectomy who do not require an unplanned secondary breast or axillary operation within 30 days after the initial procedure | Patients undergoing uni- or bilateral mastectomy as their initial proscedure for breast cancer or prophylaxis. | Patients who have a contralateral breast reoperation attributed to plastic surgeon for a complication in a breast not operated on by the breast surgeon Patients with autologous flap necrosis attributed to plastic surgeon |

Patient underwent lumpectomy as his or her initial operation | Outcome | Patient safety Efficiency and cost reduction |

Care experience Per capita cost |

QM quality measure; NQS National Quality Strategy; IHI Institute for Healthcare Improvement; PQRS Physicians Quality Reporting Service; MRI magnetic resonance imaging; ASBS American Society of Breast Surgeons; LCIS Lobular carcinoma in situ; DCIS ductal carcinoma in situ; SSI surgical site infection

aExceptions mean the patient encounter is included only in the numerator and denominator if “performance was met.”

bExclusions mean the patient encounter is never included in the numerator or denominator

cDonabedian domain40

dNational Quality Strategy domain41

eInstitute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim45

Each of our QMs underwent vetting in our electronic patient registry (Mastery) by a workgroup before submission to CMS. During this surveillance, a QM was modified, retired, or advanced to the QCDR program based on member input and ASBrS Executive Committee decisions.

Patient Encounters

To calculate the total number of provider-patient-measure encounters captured in Mastery, we summed the total reports for each individual QM for all study years and all providers who entered data.

Benchmarking

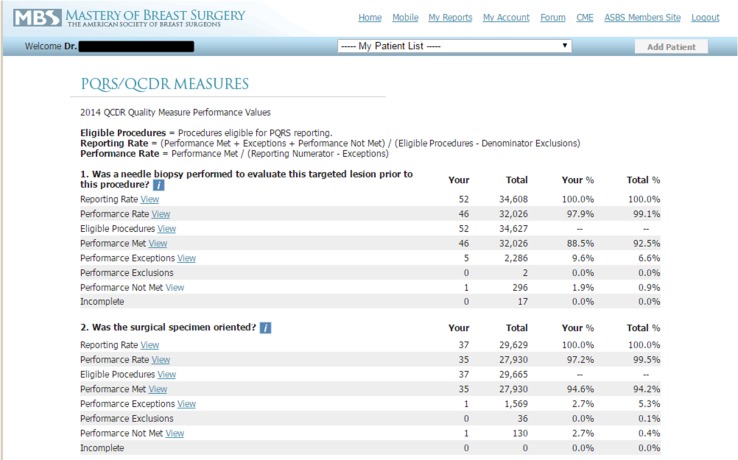

Each surgeon who entered data into Mastery was able to compare his or her up-to-date performance with the aggregate performance of all other participating surgeons (Fig. 1). The surgeons were not able to access the performance metrics of any other named surgeon or facility.

Fig. 1.

Example of real-time peer performance comparison after surgeon entry of quality measures

Data Validation

In compliance with CMS rules, a data validation strategy was performed annually. A blinded random selection of at least 3% of QCDR surgeon participants was conducted. After surgeons were selected for review, the ASBrS requested that they send the ASBrS electronic and/or paper records to verify that their office/hospital records supported the performance “met” and “not met” categories that they had previously reported to the ASBrS via the Mastery registry.

Results

Hierarchical Order and CMS QCDR Choices

The median ranking scores for 144 potential QMs ranged from 2 to 9 (Table 2). The nine QMs chosen and their ranking scores were appropriate use of preoperative needle biopsy (9.0), sentinel node surgery (9.0), specimen imaging (9.0), specimen orientation (9.0), hereditary assessment (7.0), mastectomy reoperation rate (7.0), preoperative antibiotics (7.0), antibiotic duration (7.0), and surgical-site infection (SSI) (6.0). The specifications for these QMs are presented in Table 3. The mastectomy reoperation rate and SSI are outcome measures, whereas the remainder are process of care measures.

QM Encounters Captured

A total of 1,286,011 unique provider-patient-measure encounters were captured in Mastery during 2011–2015 for the nine QCDR QMs. Performance metrics and trends for each QM are reported separately.

Data Validation

The QM reporting rate of inaccuracy by surgeons participating in the 2016 QCDR data validation study of the 2015 Mastery data files was 0.82% (27 errors in 3285 audited patient-measure encounters). Subsequent reconciliation of discordance between surgeon QM reporting and patient clinical data occurred by communication between the ASBrS and the reporting provider.

CMS Acceptance and Public Transparency

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services accepted the ASBrS QM submitted to them for PQRS participation in 2010–2013 and for QCDR in 2014–2016. In 2016, they discontinued the specimen orientation measure for future reporting and recommended further review of the mastectomy reoperation rate measure. Public reporting of 2015 individual surgeon QCDR data was posted in 2016 on the ASBrS website.

Security

To our knowledge, no breaches have occurred with any surgeon-user of Mastery identifying the performance of any other surgeon or the identity of any other surgeon’s patients. In addition, no breaches by external sources have occurred within the site or during transmission of data to CMS.

Discussion

Modified Delphi Ranking of QM

To provide relevant QM for our members, the PSQC of the ASBrS completed a hierarchal ranking of more than 100 candidate measures and narrowed the collection of QMs to fewer than a dozen using accepted methods.42,43 Although not reported here, the same process was used annually to identify new candidate QMs from 2014 to 2017 for future quality payment programs and to develop measures for the Choosing Wisely campaign.46 Based on our experience, we recommend its use for others wanting to prioritize longer lists of potential QM domains into shorter lists. These lists are iterative, allowing potential measures to be added anytime, such as after the publication of clinical trials or after new evidence-based guidelines are developed for better care. In addition, with the modified Delphi ranking process, decisions are made by groups, not individuals.

After Ranking, What Next?

Of the nine QMs selected for submission to CMS, only four had the highest possible ranking score. The reasons for not selecting some highly ranked domains of care included but were not limited to the following concerns. Some QMs were already being used by other organizations or were best assessed at the institutional, not the surgeon, level, such as the use of radiation after mastectomy for node-positive patients.32–36 Other highly ranked measures, such as “adequate history,” were not selected because they were considered standard of care.

Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy rates, a contemporary topic of much interest, was not included in our original ranking, and breast-conserving therapy (BCT) was not ranked high due to our concern that both were more a reflection of patient preferences and of regional and cultural norms than of surgeon quality. A lumpectomy reoperation QM was ranked high (7.5), but was not chosen due to disagreement within the ASBrS whether to brand this a quality measure.47,48 In some cases, QMs with lower scores were selected for use for specific reasons. For example, by CMS rules, two QMs for a QCDR must be “outcome” measures, but all our highest ranked measures were “process of care” measures.

There was occasional overlap between our QM and those of other organizations.21,32–39 In these cases, we aimed to harmonize, not compete with existing measures. For example, a patient with an unplanned reoperation after mastectomy would be classified similarly in both the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) and our program. In contrast to NSQIP, we classified a patient with postoperative cellulitis as having an SSI. Because excluding cellulitis as an SSI event has been estimated to reduce breast SSI rates threefold, adoption of the NSQIP definition would underestimate the SSI burden to breast patients and could limit improvement initiatives.49

Governance

Ranking and specifying QMs is arduous. Consensus is possible; unanimous agreement is rare. Therefore, a governance structure is necessary to reconcile differences of opinion. In our society, the PSQC solicits, ranks, and specifies QMs. A workgroup vets them for clarity and workability. In doing so, the workgroup may recommend changes. The ASBrS Executive Committee reconciles disputes and makes final decisions .

Reporting Volume

Our measurement program was successful, capturing more than 1 million provider-patient-measure encounters. On the other hand, our member participation rate was less than 20%. By member survey (not reported here), the most common reason for not participating was “burden of reporting.”

Benchmarking

“Benchmarking” is a term used most often as a synonym for peer comparison, and many programs purport to provide it.25 In actuality, benchmarking is a method for improving quality and one of nine levers endorsed by the National Quality Strategy to upgrade performance.21,23,30,50 Believing in this concept, the ASBrS and many other professional societies built patient registries that provided benchmarking.21,25,32–35 In contradistinction, the term “benchmark” refers to a point of reference for comparison. Thus, a performance benchmark can have many different meanings, ranging from a minimal quality threshold to a standard for superlative performance.24,36

Program strengths

Our patient registry was designed to collect specialty-specific QMs as an alternative to adopting existing general surgical and cross-cutting measures. Cross-cutting measures, such as those that audit medicine reconciliation or care coordination, are important but do not advance specialty-specific practice. Furthermore, breast-specific measures lessen potential bias in the comparison of providers who have variable proportions of their practice devoted to the breast. Because alimentary tract, vascular, and trauma operations tend to have higher morbidity and mortality event rates than breast operations, general surgeons performing many non-breast operations are not penalized in our program for a case mix that includes these higher-risk patients. In other words, nonspecialized general surgeons who want to demonstrate their expertise in breast surgery can do so by peer comparison with surgeons who have similar case types in our program. In addition, a condition-specific program with public transparency allows patients to make more informed choices regarding their destination for care. In 2016, individual provider report-carding for our participating surgeons began on the “physician-compare” website.51

Another strength of an organ-specific registry is that it affords an opportunity for quick Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles because personal and aggregate performance are updated continuously. Thus action plans can be driven by subspecialty-specific data, not limited to expert opinion or claims data. For example, a national consensus conference was convened, in part, due to an interrogation of our registry that identified wide variability of ASBrS member surgeon reoperation rates after lumpectomy.52,53 Other program strengths are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Strengths and limitations of the American Society of Breast Surgeons quality measurement program

| Strengths |

| Specialty measures and their specifications developed by surgeons |

| Justifiable “exceptions” to not meeting performance defined by surgeons |

| Real-time surgeon data entry lessens recall bias, abstractor error, and misclassification of attribution for not meeting a performance requirement |

| Real-time peer performance comparison |

| Large sample size of patient-measure encounters (>1,000,000) for comparisons |

| General surgeons able to compare breast surgical performance to breast-specialty surgeons |

| Low level of erroneous reporting based on audits |

| Participation satisfies American Board of Surgery Maintenance of Certification Part 4 |

| Public transparency of individual surgeon performance in 2015 on the American Society of Breast Surgeons (ASBrS) website in 2016 |

| Capability to use the program for “plan-do-study-act” cycles52,53 |

| No participation fee for members before 2016a |

| Limitations |

| Peer performance comparison not yet risk-adjusted |

| Unknown rate of nonconsecutive patient data entry |

| No significant patient or payer input into quality measure list or ranking to reflect their preferences and values54 |

| Unknown rate of surgeon “dropout” due to their perception of poor performance |

a$100.00 began 2016

Study Limitations

Although risk-adjusted peer comparisons are planned, to date, we are not providing them. In addition, only the surgeons who participate with CMS through our QCDR sign an “attestation” statement that they will enter “consecutive patients,” and no current method is available for cross-checking the Mastery case log with facility case logs for completeness. Recognizing that nonconsecutive case entry (by non-QCDR surgeons) could alter surgeon performance rates, falsely elevating them, one investigation of Mastery compared the performance of a single quality indicator between QCDR- and non–QCDR-participating surgeons.52 Performance did not differ, but this analysis has not been performed for any of the QMs described in this report. Surgeons also can elect to opt out of reporting QMs at any time. The percentage of surgeons who do so due to their perception of comparatively poor performance is unknown. If significant, this self-selected removal from the aggregate data would confound overall performance assessment, falsely elevating it.

Another limitation is our development of QMs by surgeons with minimal patient input and no payer input. As a result, we cannot rule out that these other stakeholders may have a perception of the quality of care delivered to them that differs from our perception. For example, patients might rank timeliness of care higher than we did, and payers of care might rank reoperations the highest, given its association with cost of care. We may not even be measuring some domains of care that are most important to patients because we did not uniformly query their values and preferences upfront during program development, as recommended by others.2,54 See Table 4 for other limitations.

Conclusion

In summary, the ASBrS built a patient registry to audit condition-specific measures of breast surgical quality and subsequently provided peer comparison at the individual provider level, hoping to improve national performance. In 2016, we provided public transparency of the 2015 performance reported by our surgeon participants.55,56 In doing so, we have become stewards, not bystanders, accepting the responsibility to improve patient care. We successfully captured more than 1 million patient-measure encounters, participated in CMS programs designed to link reimbursement to performance, and provided our surgeons with a method for satisfying American Board of Surgery Maintenance of Certification requirements. As public and private payers of care introduce new incentivized reimbursement programs, we are well prepared to participate with our “tested” breast-specific QMs.

Acknowledgment

We thank Sharon Grutman for ASBrS Patient Safety and Quality Committee support, Mena Jalali for Mastery Workgroup support, Mastery Workgroup members (Linda Smith, Kathryn Wagner, Eric Brown, Regina Hampton, Thomas Kearney, Alison Laidley, and Jason Wilson) for QM vetting, Margaret and Ben Schlosnagle for quality measure programming support, Choua Vang for assistance in manuscript preparation, and the Gundersen Medical Foundation and the Norma J. Vinger Center for Breast Care for financial support. We especially thank Eric and Thomas Whitacre for Mastery program development.

Disclosures

No conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Horwitz RI. Equity in cancer care and outcomes of treatment: a different type of cancer moonshot. JAMA. 2016;315:1231–1232. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Society of Clinical Oncology. The state of cancer care in America, 2017: a report by the American Society of Clinical Oncologists. J Oncol Pract. 2017;22:JOP2016020743. doi:10.1200/JOP.2016.020743. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS (eds). To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. National Academies Press Washington DC, USA, 2000. [PubMed]

- 4.Institute of Medicine (USA) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press, Washington D.C., 2001. [PubMed]

- 5.Levit LA, Balogh E, Nass SJ, Ganz PA (eds). Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., USA, 2013 (December). [PubMed]

- 6.Hewitt M, Simone JV (eds). Ensuring Quality Cancer Care. Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) National Cancer Policy Board. National Academies Press, Washington D.C., USA, 1999. [PubMed]

- 7.Davis K, Stremikis K, Schoen C, Squires D. Mirror, mirror on the wall, 2014 update: how the U.S. health care system compares internationally. The Commonwealth Fund, 16 June 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2015 at http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2014/jun/mirror-mirror.

- 8.Goodney PR, Dzebisashvili N, Goodman DC, Bronner KK. Variation in the care of surgical conditions. The Dartmouth Institute, 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015 at http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/downloads/atlases/Surgical_Atlas_2014.pdf. [PubMed]

- 9.Balogh EP, Miller BT, Ball JR (eds). Improving Diagnosis in Health Care. Committee on Diagnostic Error in Health Care; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine; The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The National Academies Press, Washington D.C., USA, 2015 (December). [PubMed]

- 10.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2016). National Healthcare Quality & Disparities Reports. Retrieved 8 December 2015 http://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/index.html.

- 11.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2013). 2012 National Healthcare Disparities Report. Retrieved 8 December 2015 at http://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhdr12/index.html.

- 12.Malin JL, Diamant AL, Leake B, et al. Quality of care for breast cancer for uninsured women in California under The Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention Treatment Act. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3479–3484. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.7491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilke LG, Ballman KV, McCall LM, et al. Adherence to the National Quality Forum (NQF) breast cancer measures within cancer clinical trials: a review from ACOSOG Z0010. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1989–1994. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0980-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warner ET, Tamimi RM, Hughes ME, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer survival: mediating effect of tumor characteristics and sociodemographic and treatment factors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2254–2261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bekelman JE, Sylwestrzak G, Barron J, et al. Uptake and costs of hypofractionated vs conventional whole breast irradiation after breast-conserving surgery in the United States, 2008–2013. JAMA. 2014;312:2542–2550. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silverstein M. Where’s the outrage? J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:78–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassett MJ, Neville BA, Weeks JC. The relationship between quality, spending, and outcomes among women with breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106. doi:10.1093/jnci/dju242. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Greenberg CC, Lipsitz SR, Hughes ME, et al. Institutional variation in the surgical treatment of breast cancer: a study of the NCCN. Ann Surg. 2011;254:339–345. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182263bb0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kent EE, Mitchell SA, Castro KM, et al. Cancer care delivery research: building the evidence base to support practice change in community oncology. Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2705–2711. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.6210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neuss MN, Malin JL, Chan S, et al. Measuring the improving quality of outpatient care in medical oncology practices in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1471–1477. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.3300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen ME, Liu Y, Ko CY, Hall BL. Improved surgical outcomes for ACS NSQIP hospitals over time: evaluation of hospital cohorts with up to 8 years of participation. Ann Surg. 2016;263:267–273. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Western Electric Company. Hawthorne Studies Collection, 1924–1961 (inclusive): a finding aid. Baker Library, Harvard Business School. Retrieved 9 December 2015 at http://oasis.lib.harvard.edu//oasis/deliver/deepLink?_collection=oasis&uniqueId=bak00047.

- 23.Tjoe JA, Greer DM, Ihde SE, Bares DA, Mikkelson WM, Weese JL. Improving quality metric adherence to minimally invasive breast biopsy among surgeons within a multihospital health care system. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:758–766. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufman CS, Shockney L, Rabinowitz B, et al. National Quality Measures for Breast Centers (NQMBC): a robust quality tool: breast center quality measures. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:377–385. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0729-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edge SB. Quality measurement in breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2014;110:509–517. doi: 10.1002/jso.23760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navathe AS, Emanuel EJ. Physician peer comparisons as a nonfinancial strategy to improve the value of care. JAMA. 2016;316:1759–1760. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.13739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The American Society of Breast Surgeons (2016). Mastery of Breast Surgery Program. Retrieved 10 June 2016 at https://www.breastsurgeons.org/new_layout/programs/mastery/background.php.

- 28.Whitacre E. The importance of measuring the measures. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1090–1091. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laidley AL, Whitacre EB, Snider HC, Willey SC. Meeting the challenge: a surgeon-centered quality program: The American Society of Breast Surgeons Mastery of Breast Surgery Pilot Program. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2010;95:23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2014). National quality strategy: using levers to achieve improved health and health care. Retrieved 13 June 2016 at http://www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality/reports/nqsleverfactsheet.htm.

- 31.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2016). 2016 Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS): Qualified Clinical Data Registry (QCDR). Participation made simple. Retrieved 13 June 2016 at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/Downloads/2016PQRS_QCDR_MadeSimple.pdf.

- 32.The National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers (2017). NAPBC Standards Manual, chapter on quality (chapter 6, p. 73). Retrieved 15 February 2017 https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/napbc/2014%20napbc%20standards%20manual.ashx#page=70.

- 33.The American College of Surgeons (2017). Commission on Cancer Quality Measures. Retrieved 15 February 2017 at https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb/qualitymeasures.

- 34.The National Consortium of Breast Centers (2017). National Quality Measures for Breast Centers. Retrieved 15 February 2017 at http://www2.nqmbc.org/quality-performance-you-should-measure/.

- 35.The American Society of Clinical Oncology (2017). Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI). Retrieved 15 February 2017 at http://www.instituteforquality.org/qopi/measures.

- 36.Del Turco MR, Ponti A, Bick U, et al. Quality indicators in breast cancer care. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2344–2356. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.06.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2016). The National Quality Measures Clearinghouse. Retrieved 13 June 2016 at http://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/search/search.aspx?term=breast. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.The American Board of Internal Medicine (2016). Choosing Wisely. Retrieved 13 June 2016 http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinician-lists/#keyword=breast.

- 39.The National Quality Forum (2016). Endorsed breast cancer quality measures. Retrieved 15 February 2017 at http://www.qualityforum.org/QPS/QPSTool.aspx#qpsPageState=%7B%22TabType%22%3A1,%22TabContentType%22%3A1,%22SearchCriteriaForStandard%22%3A%7B%22TaxonomyIDs%22%3A%5B%5D,%22SelectedTypeAheadFilterOption%22%3A%7B%22ID%22%3A13875,%22FilterOptionLabel%22%3A%22breast%22,%22TypeOfTypeAheadFilterOption%22%3A1,%22TaxonomyId%22%3A0%7D,%22Keyword%22%3A%22breast%22,%22PageSize%22%3A%2225%22,%22OrderType%22%3A3,%22OrderBy%22%3A%22ASC%22,%22PageNo%22%3A1,%22IsExactMatch%22%3Afalse,%22QueryStringType%22%3A%22%22,%22ProjectActivityId%22%3A%220%22,%22FederalProgramYear%22%3A%220%22,%22FederalFiscalYear%22%3A%220%22,%22FilterTypes%22%3A0,%22EndorsementStatus%22%3A%22%22%7D,%22SearchCriteriaForForPortfolio%22%3A%7B%22Tags%22%3A%5B%5D,%22FilterTypes%22%3A0,%22PageStartIndex%22%3A1,%22PageEndIndex%22%3A25,%22PageNumber%22%3Anull,%22PageSize%22%3A%2225%22,%22SortBy%22%3A%22Title%22,%22SortOrder%22%3A%22ASC%22,%22SearchTerm%22%3A%22%22%7D,%22ItemsToCompare%22%3A%5B%5D,%22SelectedStandardIdList%22%3A%5B%5D%7D.

- 40.Donabedian A. The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260:1743–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.1988.03410120089033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2017). The National Quality Strategy Priorities. Retrieved 14 February 2017 at https://www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality/about.htm#develnqs.

- 42.RAND Corporation. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User’s Manual 2008. Retrieved 14 February 2017 http://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1269.

- 43.Bilimoria KY, Raval MV, Bentrem DJ, et al. National assessment of melanoma care using formally developed quality indicators. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5445–51. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9965. Epub 13 October 2009. Erratum in J Clin Oncol. 2010; 28:708. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2016). 2016 Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) Toolkit: Qualified Clinical Data Registry Criteria Toolkit Measure Specifications. Retrieved 13 June 2016 https://www.cms.gov/medicare/quality-initiatives-patient-assessment-instruments/pqrs/qualified-clinical-data-registry-reporting.html.

- 45.The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (2017). Triple aim for populations. Retrieved 14 February 2017 http://www.ihi.org/Topics/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx.

- 46.Landercasper J, Bailey L, Berry T, et al. Measures of appropriateness and value for breast surgeons and their patients: the American Society of Breast Surgeons Choosing Wisely Initiative. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:3112–3118. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5327-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schwartz T, Degnim AC, Landercasper J. Should re-excision lumpectomy rates be a quality measure in breast-conserving surgery? Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:3180–3183. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morrow M, Harris JR, Schnitt SJ. Surgical margins in lumpectomy for breast cancer: bigger is not better. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:79–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1202521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Degnim A, Throckmorton A, Boostrom S, et al. Surgical-site infection after breast surgery: impact of 2010 CDC reporting guidelines. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:4099–4103. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2448-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Campion FX, Larson LR, Kadlubek PJ, Earle CC, Neuss MN. Advancing performance measurement in oncology: quality oncology practice initiative participation and quality outcomes. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(3 Suppl):31s–35s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2016). Physician Compare. Retrieved 14 February 2017 at https://www.medicare.gov/physiciancompare/.

- 52.Landercasper J, Whitacre E, Degnim AC, Al-Hamadani M. Reasons for re-excision after lumpectomy for breast cancer: insight from the American Society of Breast Surgeons Mastery(SM) database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:3185–3191. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3905-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Landercasper J, Attai D, Atisha D, et al. Toolbox to reduce lumpectomy reoperations and improve cosmetic outcome in breast cancer patients. The American Society of Breast Surgeons Consensus Conference. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22:3174–3183. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4759-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fayanju OM, Mayo TL, Spinks TE, et al. Value-based breast cancer care: a multidisciplinary approach for defining patient-centered outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:2385–2390. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.The American Society of Breast Surgeons (2016). Quality Measures and their specifications for CMS programs. Retrieved 15 February 2017 at https://www.breastsurgeons.org/new_layout/programs/mastery/pqrs.php.

- 56.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2015). 2015 Physician Quality Reporting System Qualified Clinical Data Registries: The American Society of Breast Surgeons QCDR, p. 42. Retrieved 3 April 2017 at https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/Downloads/2015QCDRPosting.pdf.

- 57.The National Quality Forum (2017). Measure evaluation and importance criteria for quality measure development. Retrieved 15 February 2017 at http://www.qualityforum.org/docs/measure_evaluation_criterias.aspx.