Abstract

Cell walls are not only a protective barrier surrounding protoplasts but serve as signaling platform between the extracellular environment and the intracellular physiology. Ions of heavy metals and trace elements, summarized to metal ions, bind to cell wall components, trigger their modification and provoke growth responses. To examine if metal ions trigger cell wall sensing receptor like kinases (RLKs) of the Catharanthus roseus RLK1-like (CrRLK1L) family we employed a molecular genetic approach. Quantitative transcription analyses show that HERCULES1 (HERK1), THESEUS1 (THE1), and FERONIA (FER) were differently regulated by cadmium (Cd), nickel (Ni), and lead (Pb). Growth responses were quantified for roots and etiolated hypocotyls of related mutants and overexpressors on Cd, copper (Cu), Ni, Pb, and zinc (Zn) and revealed a complex pattern of gene specific, overlapping and antagonistic responses. Root growth was often inversely affected to hypocotyl elongation. For example, both HERK genes seem to negatively regulate hypocotyl elongation upon Cd, Ni, Zn, and Pb while they support root growth on Cd, Cu, and Ni. The different THE1 alleles exhibited a similar effect between roots and hypocotyls on Ni, where the loss-of-function mutant was more tolerant while the gain of function mutants were hypersensitive indicating that THE1 is mediating Ni specific inhibition of hypocotyl elongation in the dark. In contrast hypocotyl elongation of the knock-out mutant, fer-4, was hypersensitive to Ni but exhibited a higher tolerance to Cd, Cu, Pb, and Zn. These data indicate an antagonistic action between THE1 and FER in relation to hypocotyl elongation upon excess of Ni. FERs function as receptor for rapid alkalinization factors (RALFs) was tested with the indicator bromocresol purple. While fer-4 roots strongly acidified control and metal ion containing media, the etiolated hypocotyls alkalized the media which is consistent with the already shorter hypocotyl of fer-4. No other CrRLK1L mutant exhibited this phenotype except of the THE1:GFP overexpressor on Ni suggesting that THE1 might be involved in Ni induced and hypocotyl specific RALF signaling and growth regulating pathway. Overall, our findings establish a molecular link between metal ion stress, growth and the cell wall integrity sensors of the CrRLK1L family.

Keywords: cadmium, copper, lead, nickel, zinc, alkalinization, root growth, hypocotyl elongation

Introduction

Heavy metals and trace elements in excess as well as deficiency in soils impose a major challenge to plant growth in general and crop productivity. From studies of metal ion tolerant and hyperaccumulating metallophytes as well as sensitive plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana we learnt that excess of metal ions induce a complex network of responses thoroughly reviewed in DalCorso et al. (2013) and Singh et al. (2016). The regulation of metal ion homeostasis involves increased biosynthesis of chelators as well as efflux and influx transporters essential for compartmentalization. Another strategy to prevent or reduce uptake of metals is by restricting metal ions to the cell wall. The cell wall, rich in functional carbohydrate originated carboxyl and hydroxyl as well as protein derived sulfhydryl and histidyl groups plays a key role in the immobilization of metal ions (Krzesłowska, 2011). Metal ion immobilization in the cell wall is mainly mediated by the pectic polysaccharide homogalacturonan (Pelloux et al., 2007). The capacity of binding is enhanced by the activity of cell wall-associated pectin-methylesterases (PMEs) or pectin-acetylesterase (PAEs) exposing free negatively charged carboxyl groups. They form salt bridges contributing to the mechanical strength of cell walls. Mainly calcium (Ca) is used in theses so called “egg boxes” but other metals ions with often higher affinities such as aluminum (Al), copper (Cu), lead (Pb), zinc (Zn), cadmium (Cd), cobalt (Co), nickel (Ni), barium (Ba), strontium (Sr), manganese (Mn), magnesium (Mg), iron (Fe), chromium (Cr), and mercury (Hg) have been shown to bind to de-esterified pectins (Dronnet et al., 1996; Kartel et al., 1999; Meychik et al., 2011). Expression studies in diverse plants show that cell wall modifying enzymes were upregulated upon metal ion stress (Hassinen et al., 2007; Konlechner et al., 2013). Also PME activities and structural modifications of pectins change upon metal ion treatments and are related to metal ion tolerance and growth responses (Paynel et al., 2009; Douchiche et al., 2010; Weber et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013; El-Moneim et al., 2014; Muschitz et al., 2015; Geng et al., 2017) and reviewed in Parrotta et al. (2015).

Pectin, highly de-esterified pectates and their degradation products are important components of the cell wall integrity pathways (Wolf et al., 2012; Voxeur and Höfte, 2016). It has been shown that pectins and oligogalacturonic acids bind to the extracellular domain of and activate WAK1 and WAK2, members of the WALL ASSOCIATED KINASES gene family (Decreux and Messiaen, 2005; Decreux et al., 2006; Kohorn et al., 2006). Furthermore, WAKs and WAK-LIKE receptors (WAKLs) are involved in the regulation of cell expansion and responses to metal ions (Lally et al., 2001; Wagner and Kohorn, 2001; Hou et al., 2005). Apart from WAK(L)s another pectin-associated kinase, proline-rich extensin-like receptor kinase 4 (PERK4), is involved in drought stress mediated growth responses (Bai et al., 2009). Also, several leucine-rich repeat (LRR) receptor like kinases (RLKs) are involved in cell wall integrity pathways related to pathogen signaling and are necessary for the synthesis of cell wall components upon high sucrose and NaCl conditions (Xu et al., 2008; Engelsdorf and Hamann, 2014).

In this study we focused on the Catharanthus roseus RLK1-like (CrRLK1L) protein family. The CrRLK1L family consists of 17 members which all share an extracellular domain homologous to the animal malectin protein with putative carbohydrate binding capacity. Therefore the CrRLK1L malectin-like domains might bind to oligo- or polysaccharides from cell wall polymers, by-products of cell wall degradation, or membrane-associated or secreted glycosylated proteins (Schallus et al., 2008; Boisson-Dernier et al., 2011). Recently it has been demonstrated that the CrRLK1L member, FERONIA (FER), is the receptor for peptides of the RAPID ALKALINIZATION FACTOR family (Haruta et al., 2014) while the ligands for the other members are still disclosed. CrRLK1L proteins play diverse roles during fertilization (Escobar-Restrepo et al., 2007; Boisson-Dernier et al., 2009; Miyazaki et al., 2009) but are also important during vegetative development and in plant pathogen interactions (Bai et al., 2014; Gachomo et al., 2014; Nissen et al., 2016; Stegmann et al., 2017).

Here, we focus on the four CrRLK1L members which regulate cell expansion and growth of seedlings: FER, THESEUS1 (THE1), HERCULES1 (HERK1), and HERK2 (Hématy et al., 2007; Guo et al., 2009a,b; Merz et al., 2017) and their role in growth responses on elevated concentrations of Cd, Cu, Ni, Pb, and Zn. With the help of loss- and gain-of-function alleles, a complex pattern of gene specific, overlapping and antagonistic reactions was revealed. Root growth was often inversely affected to hypocotyl elongation. Antagonistic roles of the two HERK genes and FER versus THE1 were discovered in relation to root growth on Cu, in relation to hypocotyl elongation on Pb and Zn, and between THE1 and FER on Ni. The effect of metal ions on the acidification ability was evaluated with bromocresol purple indicator medium. While fer-4 roots strongly acidified control and metal ion containing media, etiolated hypocotyls alkalized the media which is consistent with the fer-4 elongation defect. No other CrRLK1L mutant exhibited this phenotype except for the THE1:GFP overexpressor on Ni suggesting that THE1 might be involved in an Ni induced and hypocotyl specific rapid alkalinization factor (RALF) signaling and growth regulating pathway. Overall, our findings establish a molecular link between metal ion stress, growth and the cell wall integrity sensors of the CrRLK1L family.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material

Col-0 was used as wild type. T-DNA mutants were all in Col-0 background and provided either by the SALK collection (Alonso et al., 2003), herk1 (SALK_008043), herk2.1 (SALK_105055), herk2.2 (SALK_107146), the SAIL collection (Sessions et al., 2002), the1-4 (SAIL_683_H03), and the GABI-Kat collection (Kleinboelting et al., 2012), fer-4 (GABI_GK106A06). The loss-of-function allele, the1-6, was isolated in a suppressor screen of ctl1-1/pom and described in Merz et al. (2017). The THE1:GFP overexpression line was described in Hématy et al. (2007).

Growth Conditions

Seeds were surface-sterilized in 5% sodium hypochlorite and rinsed three times with sterile deionized water and then transferred to nutrient agar medium plates containing 1/10 strength Hoagland salts, 1% (w/v) sucrose and 1% (w/v) agar (Duchefa). For metal ion treatments metal salts were added after autoclaving to final concentrations of 10 μM CdCl2, 5 μM CuSO4, 15 μM NiSO4, 100 μM Pb(NO3)2, and 100 μM ZnSO4. After 2 days of imbibition at 4°C in the dark, plates were vertically incubated in a growth chamber at 22°C with constant light (80 μmol m2 s-1). For measurements of etiolated hypocotyls, plates were wrapped in aluminum foil after exposure to light for 5 h. Isoxaben treatment for gene expression analyses was essentially done as described in Merz et al. (2017). Ni treatment for gene expression analyses was done for 6 h on 4 days after germination (dag) etiolated seedlings.

Bromocresol Purple (BCP) Plates

For pH assays sterilized seeds were placed on nutrient agar plates as described above supplemented with 150 μM BCP and metal ions in indicated concentrations. Plates were scanned on day 5 after germination.

Growth Analysis

The plates were scanned on days 3, 4, and 5 after germination for root growth and on day 5 after germination for hypocotyl measurements. The lengths were evaluated with the ImageJ software by freehand tracking.

RNA Isolation and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA of 10–12 day old seedlings germinated and grown on control and metal ion supplemented medium were snap frozen and isolated using a LiCl/CTAB method. After grinding roughly 100 mg frozen seedlings 1 mL of pre-heated RNA extraction buffer (2% [w/v] hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide, CTAB; 2% [w/v] polyvinylpyrrolidone, PVP; 100 mM Tris/HCl pH 8.0; 25 mM EDTA; 2 M NaCl; 0.5 g/L spermidine and 2.7% [v/v] 2-mercaptoethanol) was added, mixed and incubated at 65°C for 5 min. CTAB was removed through two times separation with 1 mL of ice-cold chloroform: isoamylalcohol (24:1) and centrifugation at 4°C. RNA in the supernatant was precipitated with 250 μL 10 M LiCl at 4°C for more than 1.5 h. After centrifugation and EtOH washes the pellet was dissolved in 20 μL RNase free water and stored at -80°C. RNA was quantified with the Qubit (Invitrogen) and the NanoDrop systems. RNA integrity was controlled on Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer using RNA Nanochip. RNA samples were treated with DNaseI using the TURBO DNA-freeTM kit (Ambion). cDNAs were synthesized from 4 μg total RNA using the Transcriptor reverse transcriptase (Roche) with 500 pmol of oligo(dT)18 primer. The reaction was stopped at 85°C for 5 min without further treatment according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was diluted 20 times with distilled water and tested by PCR using specific primers flanking an intron sequence to confirm the absence of genomic DNA contamination. cDNA synthesis for the THE1 downstream gene expression was done as described in Merz et al. (2017).

Reverse Transcription (RT)-qPCR Data Analysis

AP2M (ADAPTOR PROTEIN-2 MU-ADAPTIN) has been validated to be the most stably expressed gene among eight tested and was used to normalize the RT-qPCR data (Gutierrez et al., 2012). CT and PCR efficiency (E) values were used to calculate expression using the formula ET(CTctr-CTm)/ER(CTctr-CTm), where T is the target gene and R is the reference gene, CT is the crossing threshold value, m refers to cDNA from the metal ion treated seedlings, and ctr refers to cDNA from the control medium. All RT-qPCR results presented are means from three independent biological replicates and for each independent biological replicate, the relative transcript amount was calculated as the mean of three technical replicates, using the method for calculation of SE values in relative quantification recommended by Rieu and Powers (2009). RT-qPCR for the THE1 downstream gene expression was done as described in Merz et al. (2017). Primers used for the RT-qPCRs are summarized in Supplementary Table 2.

Results And Discussion

Members of the CrRLK1L Family Are Induced upon Metal Ion Exposure

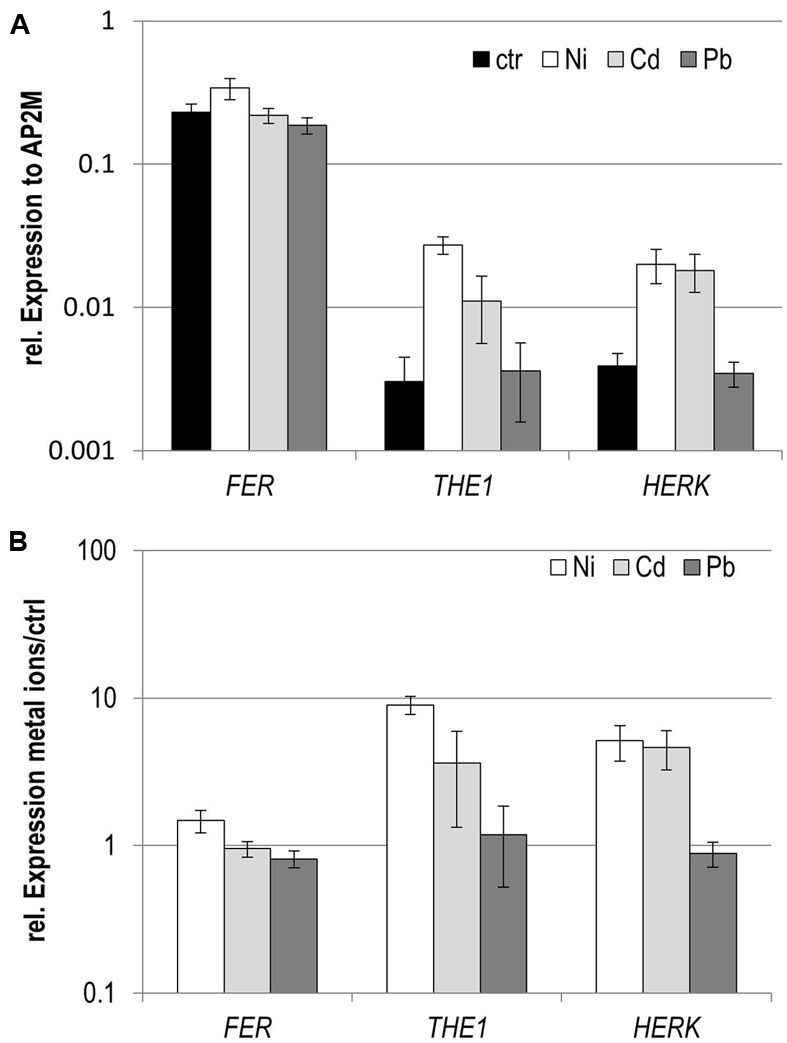

In an expression survey for genes responsive to the metal ions Cd, Ni, and Pb in seedlings, the CrRLK1L members THE1, FER, and HERK1 exhibited a remarkable expression pattern. All three were induced by Ni, only slightly for FER but strongly for HERK1 and THE1 (Figure 1). Pb did not induce any transcriptional regulation whereas Cd triggered upregulation of THE1 and HERK1.

FIGURE 1.

Expression analyses of CrRLK1L members in seedlings exposed to different metal ions to different metal ions. (A) Expression normalized to the reference gene AP2M, (B) expression relative to the control conditions. Data are mean and SE of three biological experiments with each three technical repeats.

Root and Etiolated Hypocotyl Growth Differ in Response to Metal Ion Medium

Growth and cell expansion responses of germinating Arabidopsis seedlings to elevated metal ion concentrations depend strongly on the composition of the growth medium and on the cation exchange capacity of the agar. The high cation concentration such as provided by the frequently used 1x Murashige and Skoog medium (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) interferes with the uptake of additional metal ions. On 1x MS medium 400 μM Zn and 40 μM Cd were needed to observe a slight root length reduction for Zn and a 30% reduction for Cd (Kobae et al., 2004). A comparable experiment with germinating seedlings on 1/10 Hoagland medium supplemented with metal ions needed only 50 μM Zn for a 43.2% and 2 μM Cd for a 57.6% root growth inhibition (Tennstedt et al., 2009). Since the MS medium is also Fe- satiated and Cu-deficient all metal ion experiments were performed on 1/10 Hoagland medium (Supplementary Table 1).

Root growth depends on two parameters, the rate of cell division and cell expansion, while dark stimulated hypocotyl growth depends solely on cell expansion. To separate the cell division from cell expansion effects, root growth was determined on seedlings germinating and grown for 5 days in the light and hypocotyl elongation was assessed on 5 dag dark-grown seedlings. In both sets of experiments identical 1/10 Hoagland media supplemented with either 10 μM Cd, 5 μM Cu, 15 μM Ni, 100 μM Pb, or 100 μM Zn were used.

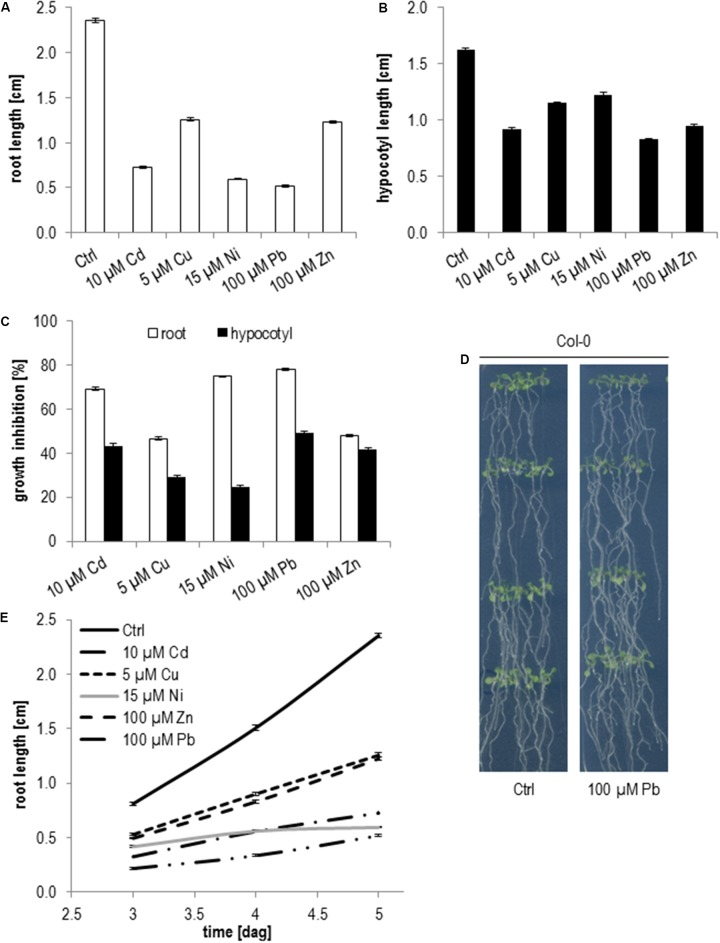

Generally, hypocotyl elongation is less sensitive to metal ions (Figures 2A–C). While on 10 μM Cd root growth was reduced by 70% in relation to control medium the growth inhibition of hypocotyls was only 43%. Similar results were obtained for 5 μM Cu with 46% root and 30% hypocotyl inhibition, 100 μM Zn with 47% root and 41% hypocotyl inhibition, 15 μM Ni with 74% root and 25% hypocotyl inhibition and 100 μM Pb with 78% root and 49% hypocotyl inhibition (Figure 2C). The most dramatic difference between root and hypocotyl growth inhibition was seen for Ni followed by Pb and Cd (Figure 2C) indicating that these metal ions might influence cell division more severely than cell expansion. It might also be possible that cell expansion in the root is differently affected by these metal ions than in etiolated hypocotyls. The difference between root and hypocotyl growth is particularly true for Ni where root growth rate was continuously declining and nearly stopped 5 days after germination (dag) (Figure 2D). Pb shows the opposite effect and root growth recovered starting at 5 dag and roots reached nearly the same length as wild type at 11 dag (Figure 2E).

FIGURE 2.

Root growth and etiolated hypocotyl elongation of Col-0 seedlings upon elevated metal ion concentrations. (A) Root length 5 days after germination, (B) hypocotyl length after 5 days of germination in the dark, (C) growth inhibition relative to control medium, (D) root growth between days 3 and 5 after germination, (E) seedlings on control and Pb 11 days after germination. Shown are mean and SE of at least three biological replicates with 20 seedlings each.

Apart of the dissimilar effects of metal ions on cell division and cell expansion another explanation for the differing sensitivities between root and hypocotyl growth would be that metal ion transport to hypocotyls is less effective. Data on metal ion concentrations in separated roots and hypocotyls and quantifications of the cell division rate and cell sizes would resolve these possibilities. Although the results of these analyses would contribute to the understanding of the root/hypocotyl response differences, the focus of this study was to determine if members of the CrRLK1L family are involved in mediating growth responses to metal ions.

HERCULES1 and 2 Negatively Regulate Hypocotyl Elongation on Cd, Ni, Zn, and Pb While They Support Root Growth on Cd, Cu, and Ni

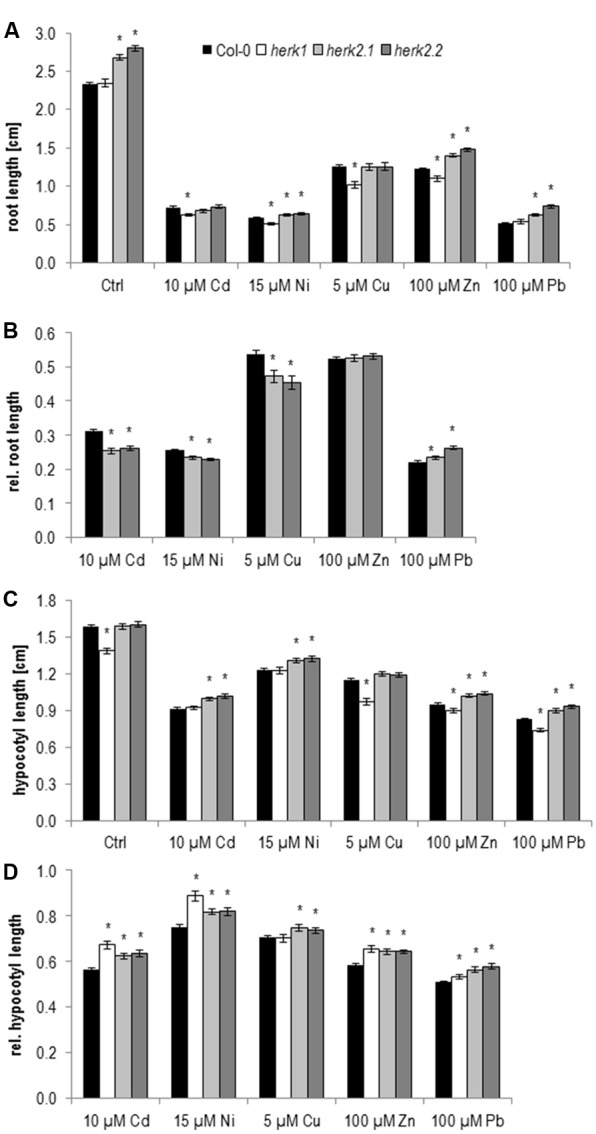

Previous growth assays with single mutants impaired in HERK1 and HERK2 expression did not show any obvious growth phenotype. But the mutants developed strong cell elongation defects in combination with the the1-4 allele (Guo et al., 2009a,b). However the1-4 turned out to be a hypermorphic allele. Thus the growth defects of the double and triple mutants indicate that HERK1 and HERK2 act antagonistically and not redundantly to THE1 (Merz et al., 2017). On 1/10 Hoagland control medium, roots of herk1 seedlings grow similarly to wild type in contrast to both herk2 alleles, which exhibited a significantly faster root growth (Figure 3A and Table 1).

FIGURE 3.

Root growth and etiolated hypocotyl elongation of herk1 and herk2 alleles upon elevated metal ion concentrations at 5 days after germination. (A) Absolute root lengths, (B) relative root lengths of herk2 alleles, (C) absolute hypocotyl lengths, (D) relative hypocotyl lengths. Shown are mean and SE of at least three biological replicates with 20 seedlings each. Stars indicate significant differences according to Student’s t-tests with ∗p < 0.05 to wild type (A,C), wild type and control medium (B,D).

Table 1.

Summary of the significant growth and elongation responses in comparison to wild type.

| Genotype | ctrl |

Cd |

Cu |

Ni |

Pb |

Zn |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organ | r | h | r | h | r | h | r | h | r | h | r | h |

| herk1 | = | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | = | ↓ | ↑ | = | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

| herk2.1 | ↑ | = | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | = | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | = | ↑ |

| herk2.2 | ↑ | = | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | = | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | = | ↑ |

| the1-6 | ↓ | = | ↓ | = | = | = | ↑ | ↑ | = | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

| the1-4 | = | ↓ | ↑ | = | ↓ | = | ↑ | ↓ | = | ↑ | = | ↑ |

| THE1:GFP | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | = | = | = | ↑ |

| fer-4 | ↓ | ↓ | = | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | = | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

Data of roots and hypocotyls are indicated with r and h, respectively. In case growth on control medium was already significantly different between wild type and the CrRLK1L mutants the significances of the normalized data are employed.

On metal ion supplemented medium root growth of herk1 seedlings is stronger inhibited upon Cd, Ni, Cu, and Zn than wild type. Since the two herk2 alleles already grow faster on control medium, analyzing the effect of metal ions on these mutants by only looking at the absolute root length data might be misleading. Therefore, their root growth on metal ions was normalized to control conditions (Figure 3B and Table 1). These analyses revealed that the apparent higher tolerance to Ni, and Zn diminished and only the reduced lead response remained while an enhanced Cd, Cu, and Ni sensitivity was revealed. In summary, both HERK genes are likely to be important to support root growth upon higher Cd, Cu, and Ni concentrations while the Zn response is HERK1 specific and the Pb response is HERK2 specific.

As with wild type the hypocotyl elongation in the mutants differs from root growth responses. Already on control medium herk1 elongates significantly less than wild type and the two herk2 alleles (Figure 3C and Table 1). Therefore, normalization to control conditions was necessary to reveal that hypocotyl elongation of herk1 was less disturbed by Cd, Ni, Zn, and Pb than wild type (Figure 3D and Table 1). Identical responses were found in the two herk2 mutants (Figures 3C,D and Table 1). In conclusion, both HERK genes appear to mediate the inhibition of hypocotyl elongation upon Cd, Ni, Zn, and Pb while they support root growth on Cd, Cu, and Ni.

THESEUS1 Is Mediating Ni Specific Inhibition of Hypocotyl Elongation in the Dark without Cell Wall Damage Responses

THE1 signaling negatively affects cell expansion upon inhibition of cellulose synthesis (Hématy et al., 2007; Merz et al., 2017). Therefore THE1 is the strongest candidate to uncover metal ion induced cell wall damage responses. Well-characterized loss-of-function and gain-of-function alleles were available to compare their responses to metal ions.

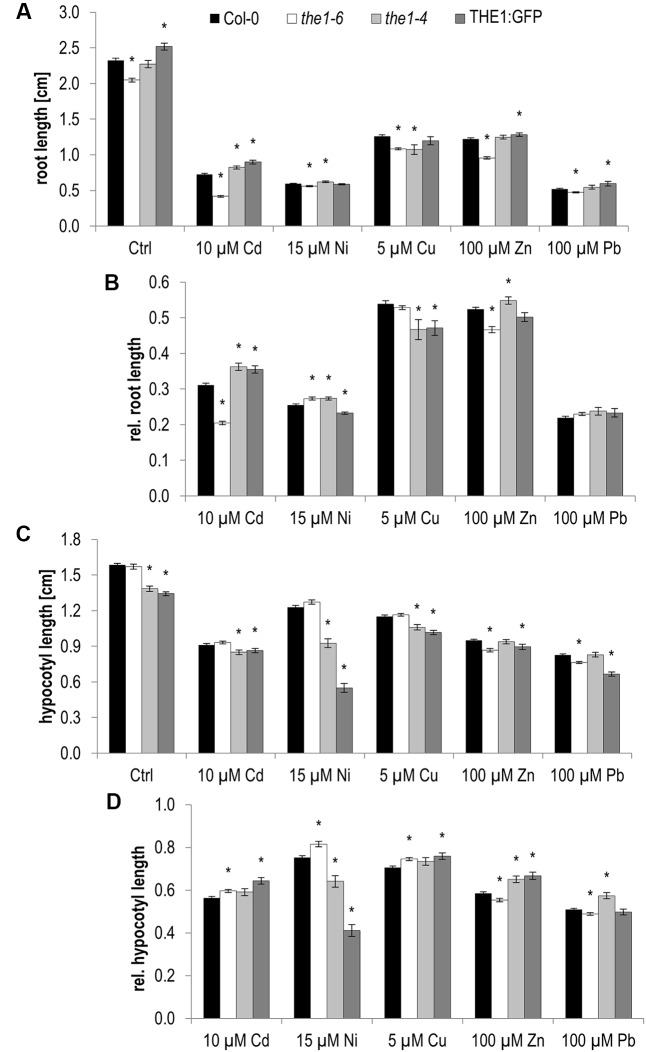

Already on control medium root growth of THE1-related knock-out and overexpression lines behaved inversely (Figure 4A and Table 1). While the loss-of-function mutant the1-6 developed shorter roots, roots of the THE1:GFP overexpressor grew faster than wild type. Similar contrasting root growth responses were significant on Cd and Ni. On Cu only THE1:GFP and the hypermorphic allele the1-4 developed shorter roots as did the1-6 on Zn (Figure 4B and Table 1).

FIGURE 4.

Root growth and etiolated hypocotyl elongation of different the1 alleles on medium supplemented with high metal ion concentrations at 5 days after germination. (A) Absolute root lengths, (B) relative root lengths, (C) absolute hypocotyl lengths, (D) relative hypocotyl lengths. Shown are mean and SE of at least three biological replicates with 20 seedlings each. Stars indicate significant differences according to Student’s t-tests with ∗p < 0.05 to wild type (A,C), wild type and control medium (B,D).

We previously showed that the hypermorphic the1-4 expresses a transcript encoding a predicted membrane-associated truncated protein lacking the kinase domain. Differences between THE1:GFP and the hypermorphic the1-4 allele, as seen on control, Ni and Zn, possibly relate to the missing cytoplasmic domain in the1-4 which might be important for feedback regulation (Merz et al., 2017).

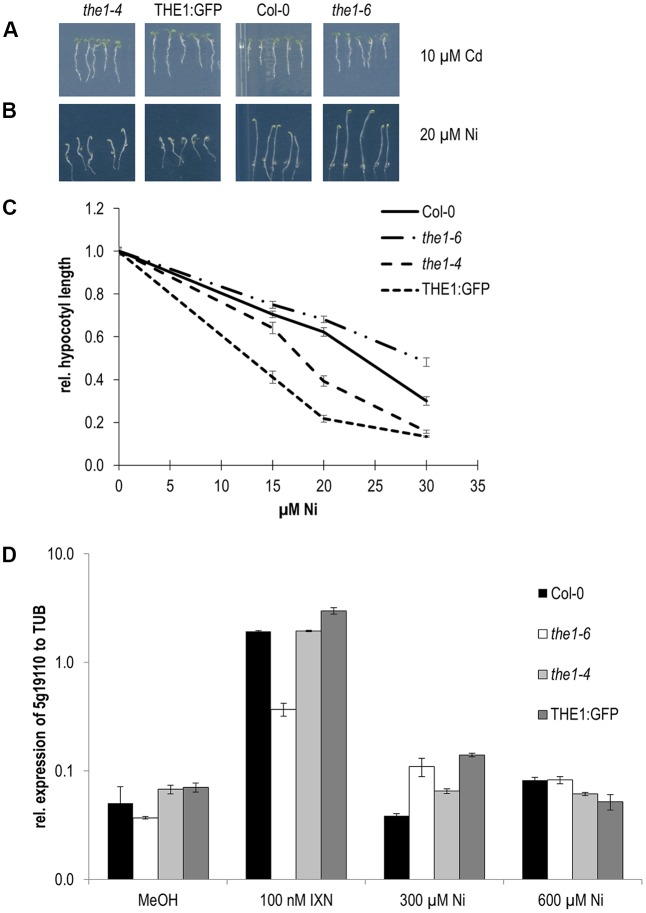

Hypocotyl elongation in the dark behaved different to roots for the1-6 on control Cd, and Pb, for THE1:GFP on control, Cu and Zn and for the1-4 on all conditions (Figures 4C,D and Table 1). While in roots the strongest effect was shown by the1-6 on Cd, for hypocotyls it was on Ni by the1-4 and THE1:GFP (Figure 5A). The opposing effects of the loss- and gain-of function alleles on hypocotyl elongation were even more distinct on 20 and 30 μM Ni (Figures 5B,C). These results indicate that THE1 mediates Ni specific inhibition of hypocotyl elongation in the dark and promotes Cd specific growth tolerance in roots.

FIGURE 5.

Responses of THE1 alleles to Cd and Ni. (A) Root growth on Cd, (B) etiolated hypocotyl elongation on Ni, (C) dose responses of Ni on etiolated hypocotyls, (D) expression of a downstream gene of the THE1 mediated cell wall damaging signaling pathway upon treatment with the cellulose biosynthesis inhibitor isoxaben (IXN), mock (MeOH) and different concentrations of Ni.

As mentioned above THE1 is known to inhibit cell elongation in hypocotyls upon cell wall damage. Therefore, we examined if Ni induces cell wall damage specific responses such as the expression of the downstream gene in the THE1 signaling pathway, EDGP/At5g19110. The expression of At5g19110 was strongly induced in the overexpressor and the hypermorphic alleles and did not respond in the loss-of-function allele, the1-6 in chemically induced cell wall damage by treatment with the cellulose biosynthesis inhibitor isoxaben. Upon Ni treatment a very low expression in the different THE1 alleles was quantified with no significant alterations to wild type (Figure 5D). These data suggest that Ni perception by THE1 is independent of cell wall damage specific gene expression responses.

FERONIA Mediates Growth Inhibition of Hypocotyl on Cd, Cu, Pb, and Zn While it Promotes Growth on Ni

FER is the best studied member of the CrRLK1L gene family. FER has been identified due to its crucial function during pollen-tube ovule interaction (Escobar-Restrepo et al., 2007) but is also important for bacterial pathogen interaction (Keinath et al., 2010; Stegmann et al., 2017), mechanosensing (Shih et al., 2014) and in the antagonistic cross-talk between ABA and auxin in vegetative tissues (Yu et al., 2012). Mutants of FER exhibit diverse pleotropic phenotypes. They are stunted, develop smaller leaves (Guo et al., 2009b) and shorter etiolated hypocotyls which are hypersensitive to ethylene and insensitive to brassinosteroids (Deslauriers and Larsen, 2010). Moreover fer mutants develop shorter root hairs (Duan et al., 2010; Du et al., 2016) and larger seeds (Yu et al., 2014) and exhibit a reduced gravitropic response which correlates with less apoplastic alkalization at the lower side of gravistimulated roots (Barbez et al., 2017).

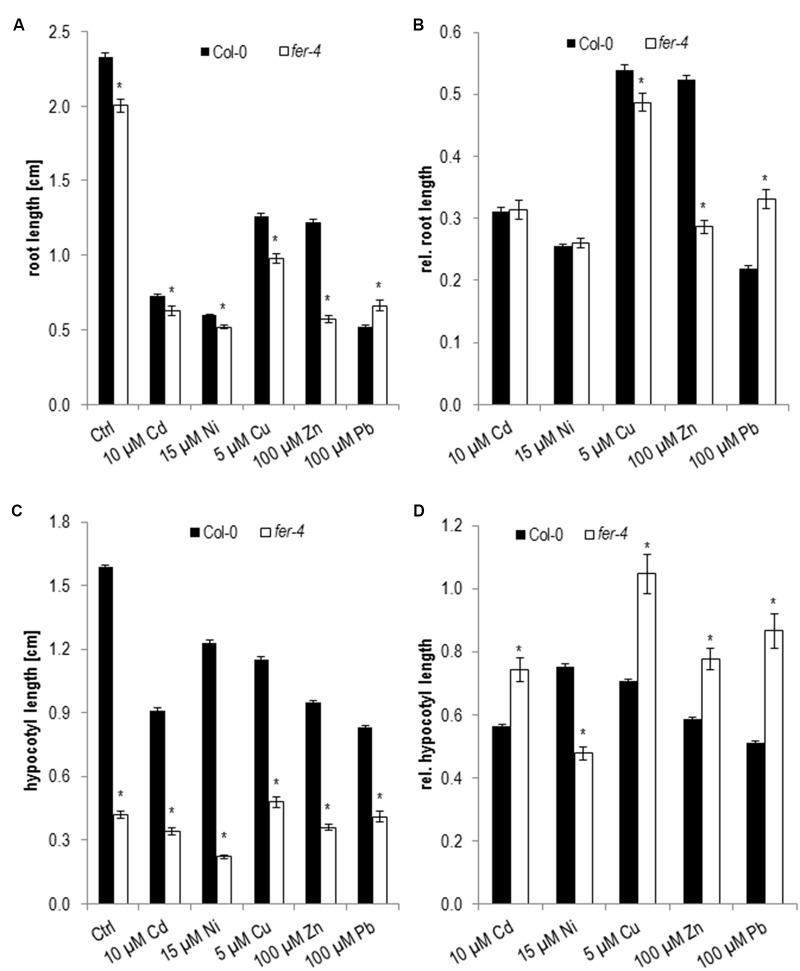

In our growth analyses root lengths of 5 days old fer-4 seedlings were significantly shorter on control medium and in most metal ion treatments except on Pb (Figure 6A and Table 1). However when root growth was normalized to control conditions fer-4 was hypersensitive to Zn and Cu while it was more tolerant to Pb (Figure 6B and Table 1). In concordance with published data etiolated fer-4 hypocotyl reached only 25% of the size of wild type (Figure 6C and Table 1). Thus the different effects of the metal ions were revealed after normalization to control conditions (Figure 6D and Table 1) and showed that fer-4 is hypersensitive to Ni and has a higher tolerance to all other tested metal ions.

FIGURE 6.

Root growth and hypocotyl elongation of fer-4 on medium supplemented with elevated metal ion concentrations at 5 dag. (A) Absolute root length, (B) corresponding relative root lengths, (C) absolute hypocotyl lengths, (D) corresponding relative hypocotyl lengths. Shown are mean and SE of at least three biological replicates with 20 seedlings each. Stars indicate significant differences according to Student’s t-tests with ∗p < 0.05 to wild type (A,C), wild type and control medium (B,D).

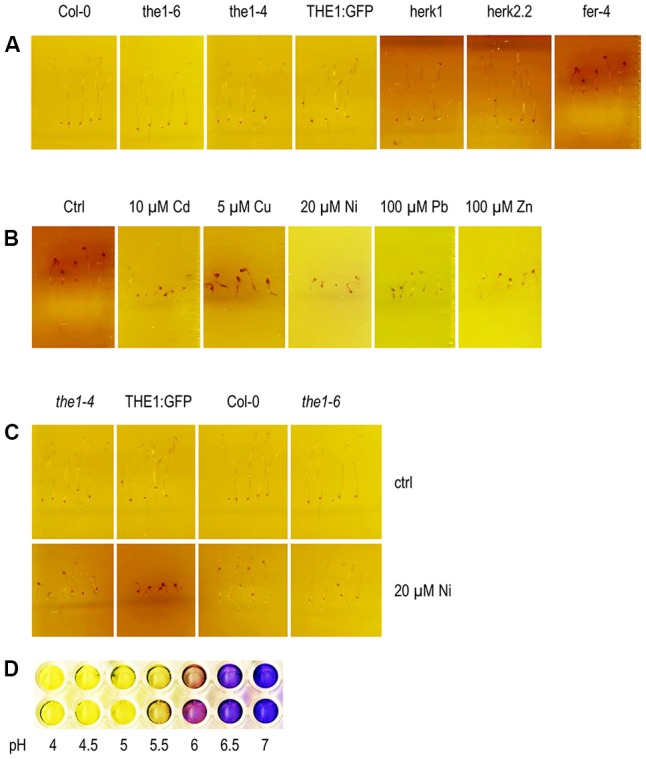

Medium Alkalinization of Etiolated Seedlings Is Constitutive in fer-4 Hypocotyls and Ni Specific in the THE1 Overexpressor

FER binds and is activated by secreted peptides of the RALF family (Haruta et al., 2014) triggering alkalinization of the apoplast. This alkalinization is thought to counteract the acidification crucial for cell expansion. Light grown fer-4 seedlings acidified a bath medium faster than wild type which is indicative for a higher plasma membrane H+-ATPase activity (Haruta et al., 2014).

Since growth of etiolated hypocotyl depends on rapid cell expansion we tested the acidification capacity of the CrRLK1L mutants on control medium and upon metal ion treatments (Figures 7A–C). All genotypes acidified the medium supplemented with the pH indicator bromocresolpurple (BCP) (Figure 7D). Only fer-4 exhibited a remarkable alkalinization around the hypocotyl while the root was still acidifying the medium (Figure 7B). This alkalinization might be one of the reasons why etiolated hypocotyls of fer-4 are short and indicate that the plasma membrane H+-ATPase activity is differently regulated from roots. The phenotype further suggests that FER is necessary for the acidification of etiolated hypocotyls. It is conceivable that in the absence of FER RALF expression is triggered and another receptor in the hypocotyl mediates the alkalinization. The alkalinization surrounding the fer-4 etiolated hypocotyl was still visible on medium supplemented with metal ions. Hypoctoyl mediated alkalinization of the medium is strongest on control medium, followed by Cu, Ni, and only slightly on Cd and Zn. Since, the medium supplemented with Pb has a lower pH itself the alkalinization takes longer. The only other genotype with reduced acidification capacity was the overexpressor THE1:GFP on Ni (Figure 7C and Supplementary Figure 1). Similar to fer-4, THE1:GFP developed shorter hypocotyls on Ni. It might be possible that overexpression of THE1:GFP increases the sensitivity to Ni induced hypocotyl specific RALFs and that THE1 might be involved in their signaling pathway.

FIGURE 7.

Alkalinization of the medium around etiolated hypocotyls. (A) On control medium, (B) of fer-4 on metal ions and (C) of loss- and gain-of-function alleles of THE1 on elevated Ni concentrations. (D) BCP is yellow below pH < 5.2 and purple above pH > 6.0. The contrast and brightness of the pictures were increased by 50% and 20%, respectively, except for fer-4 on Pb where only the contrast was raised to +50%.

Conclusion

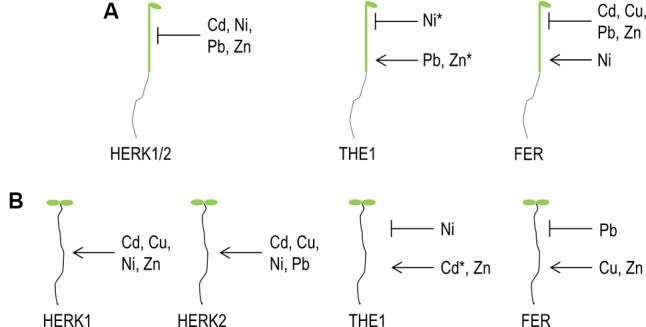

Our survey revealed a molecular link between metal ion stress, growth and the cell wall integrity sensors of the CrRLK1L family. By analyzing growth responses in roots and hypocotyls a complex network of patterns of gene specific, overlapping and antagonistic responses which are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 8 was uncovered. Few general patterns were extractable of the data: in all HERK1, HERK2 and FER mutants root growth is affected inversely to hypocotyl elongation. This tendency is also true for the different THE1 alleles but for example on Zn in the opposite direction. The hypocotyl of the gain-of-function and hypermophic alleles of THE1 behaved similar to HERK1, HERK2, and FER while the loss-of-function allele exhibited hypersensitivity toward Zn (Table 1). The difference of the metal ion mediated growth responses might arise as a result of the presence of different ligands in roots and fast expanding etiolated hypocotyls. One of the candidate ligands might be members of the large RALF gene family. RALF1 has been shown to bind and activate FER leading to the phosphorylation and inhibition of the plasma membrane H+-ATPase AHA2, reduction of the apoplast/cell wall acidification and the inhibition of cell expansion genes (Haruta et al., 2014). It is possible that other RALFs with different expression and pro-peptide processing patterns are triggering similar reactions in conjunction with other CrRLK1Ls (Wolf and Höfte, 2014). Other possible ligands related to the putative carbohydrate binding feature of the extracellular malectin-like domain might be metal ions loaded pectin/homogalacturonans or their degradation products, oligogalacturonans. Boisson-Dernier et al. (2011) proposed for the pollen specific CrRLK1L member, ANXUR1 and 2 (ANX1 and ANX2) a possible interaction between homogalacturonans. This hypothesis was based of the premature bursting of pollen tubes in the double mutants of anx1/anx2 and the pollen specific expression of pectin modifying enzymes which correlated with a specific de-/methylesterification at the pollen tube tip and thus mechanical property. A related hypothesis was presented by Wolf and Höfte (2014) proposing a feedback loop between RALF and pectin modifying enzymes. RALF induced alkalinization of the cell wall would activate PMEs which upon removal of the methyl groups lead to cell wall acidification and cell expansion. Based on this hypothesis, metal ions might be complexed by demethylesterified pectins and stiffens the cell wall prematurely before cell expansion is completed. The puzzle why different metal ions trigger specific CrRLK1Ls and why and how their signaling outcome induces opposite effects on growth remains to be solved in the future.

FIGURE 8.

Graphical summary of CrRLK1L functions on elevated metal ion concentrations. (A) Etiolated hypocotyl elongation, (B) root growth. Arrows indicate that the particular CrRLK1L protein is required to maintain growth while cross bars illustrate an inhibitory function upon specific metal ions. ∗ Indicate opposite effects of the1-6 loss-of-function versus gain-of-function alleles (the1-4, THE1:GFP) on elevated concentrations of the marked metal ion.

Author Contributions

JR and M-TH designed the study and JR, MP, and GM performed the experiments and JR, M-TH, and LG analyzed the data. M-TH and JR wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Francois Jobert for the design of the THE1, HERK1, and FER primers used in the RT-qPCR. We thank the seed stock distribution center Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (NASC), Kai Dünser for the fer-4 and Herman Höfte and Marjolaine Martin for herk1, herk2.1, and herk2.2 mutants.

Footnotes

Funding. The project was supported by a grant of the Austrian Science Fund FWF I 1725-B16 and the French National Research Agency project ANR-FWF I 1725-B16.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpls.2017.01554/full#supplementary-material

References

- Alonso J. M., Stepanova A. N., Leisse T. J., Kim C. J., Chen H. M., Shinn P. (2003). Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301 653–657. 10.1126/science.1086391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L., Ma X., Zhang G., Song S., Zhou Y., Gao L., et al. (2014). A receptor-like kinase mediates ammonium homeostasis and is important for the polar growth of root hairs in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 26 1497–1511. 10.1105/tpc.114.124586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L., Zhang G., Zhou Y., Zhang Z., Wang W., Du Y., et al. (2009). Plasma membrane-associated proline-rich extensin-like receptor kinase 4, a novel regulator of Ca2+ signalling, is required for abscisic acid responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 60 314–327. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03956.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbez E., Dünser K., Gaidora A., Lendl T., Busch W. (2017). Auxin steers root cell expansion via apoplastic pH regulation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 E4884–E4893. 10.1073/pnas.1613499114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisson-Dernier A., Kessler S. A., Grossniklaus U. (2011). The walls have ears: the role of plant CrRLK1Ls in sensing and transducing extracellular signals. J. Exp. Bot. 62 1581–1591. 10.1093/jxb/erq445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisson-Dernier A., Roy S., Kritsas K., Grobei M. A., Jaciubek M., Schroeder J. I., et al. (2009). Disruption of the pollen-expressed FERONIA homologs ANXUR1 and ANXUR2 triggers pollen tube discharge. Development 136 3279–3288. 10.1242/dev.040071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DalCorso G., Manara A., Furini A. (2013). An overview of heavy metal challenge in plants: from roots to shoots. Metallomics 5 1117–1132. 10.1039/c3mt00038a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decreux A., Messiaen J. (2005). Wall-associated kinase WAK1 interacts with cell wall pectins in a calcium-induced conformation. Plant Cell Physiol. 46 268–278. 10.1093/pcp/pci026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decreux A., Thomas A., Spies B., Brasseur R., Van Cutsem P., Messiaen J. (2006). In vitro characterization of the homogalacturonan-binding domain of the wall-associated kinase WAK1 using site-directed mutagenesis. Phytochemistry 67 1068–1079. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deslauriers S. D., Larsen P. B. (2010). FERONIA is a key modulator of brassinosteroid and ethylene responsiveness in Arabidopsis hypocotyls. Mol. Plant 3 626–640. 10.1093/mp/ssq015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douchiche O., Soret-Morvan O., Chaïbi W., Morvan C., Paynel F. (2010). Characteristics of cadmium tolerance in ‘Hermes’ flax seedlings: contribution of cell walls. Chemosphere 81 1430–1436. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dronnet V. M., Renard C. M. G. C., Axelos M. A. V., Thibault J. F. (1996). “Heavy metals binding by pectins: selectivity, quantification and characterisation,” in Progress in Biotechnology, ed. Voragen J.V.a.A.G.J. (Amsterdam: Elsevier; ), 535–540. [Google Scholar]

- Du C., Li X., Chen J., Chen W., Li B., Li C., et al. (2016). Receptor kinase complex transmits RALF peptide signal to inhibit root growth in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113 E8326–E8334. 10.1073/pnas.1609626113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Q., Kita D., Li C., Cheung A. Y., Wu H.-M. (2010). FERONIA receptor-like kinase regulates RHO GTPase signaling of root hair development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 17821–17826. 10.1073/pnas.1005366107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Moneim D. A., Contreras R., Silva-Navas J., Gallego F. J., Figueiras A. M., Benito C. (2014). Pectin methylesterase gene and aluminum tolerance in Secale cereale. Environ. Exp. Bot. 107 125–133. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2014.06.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Engelsdorf T., Hamann T. (2014). An update on receptor-like kinase involvement in the maintenance of plant cell wall integrity. Ann. Bot. 114 1339–1347. 10.1093/aob/mcu043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Restrepo J.-M., Huck N., Kessler S., Gagliardini V., Gheyselinck J., Yang W.-C., et al. (2007). The FERONIA receptor-like kinase mediates male-female interactions during pollen tube reception. Science 317 656–660. 10.1126/science.1143562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachomo E. W., Jno Baptiste L., Kefela T., Saidel W. M., Kotchoni S. O. (2014). The Arabidopsis CURVY1 (CVY1) gene encoding a novel receptor-like protein kinase regulates cell morphogenesis, flowering time and seed production. BMC Plant Biol. 14:221 10.1186/s12870-014-0221-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng X., Horst W. J., Golz J. F., Lee J. E., Ding Z., Yang Z.-B. (2017). LEUNIG_HOMOLOG transcriptional co-repressor mediates aluminium sensitivity through PECTIN METHYLESTERASE46-modulated root cell wall pectin methylesterification in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 90 491–504. 10.1111/tpj.13506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Li L., Ye H., Yu X., Algreen A., Yin Y. (2009a). Three related receptor-like kinases are required for optimal cell elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 7648–7653. 10.1073/pnas.0812346106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Ye H., Li L., Yin Y. (2009b). A family of receptor-like kinases are regulated by BES1 and involved in plant growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signal. Behav. 4 784–786. 10.1073/pnas.0812346106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez L., Mongelard G., Floková K., Pǎcurar D. I., Novák O., Staswick P., et al. (2012). Auxin controls Arabidopsis adventitious root initiation by regulating jasmonic acid homeostasis. Plant Cell 24 2515–2527. 10.1105/tpc.112.099119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haruta M., Sabat G., Stecker K., Minkoff B. B., Sussman M. R. (2014). A peptide hormone and its receptor protein kinase regulate plant cell expansion. Science 343 408–411. 10.1126/science.1244454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassinen V. H., Tervahauta A. I., Halimaa P., Plessl M., Peraniemi S., Schat H., et al. (2007). Isolation of Zn-responsive genes from two accessions of the hyperaccumulator plant Thlaspi caerulescens. Planta 225 977–989. 10.1007/s00425-006-0403-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hématy K., Sado P.-E., Van Tuinen A., Rochange S., Desnos T., Balzergue S., et al. (2007). A receptor-like kinase mediates the response of Arabidopsis cells to the inhibition of cellulose synthesis. Curr. Biol. 17 922–931. 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou X., Tong H., Selby J., Dewitt J., Peng X., He Z. H. (2005). Involvement of a cell wall-associated kinase, WAKL4, in Arabidopsis mineral responses. Plant Physiol. 139 1704–1716. 10.1104/pp.105.066910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartel M. T., Kupchik L. A., Veisov B. K. (1999). Evaluation of pectin binding of heavy metal ions in aqueous solutions. Chemosphere 38 2591–2596. 10.1016/S0045-6535(98)00466-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keinath N. F., Kierszniowska S., Lorek J., Bourdais G., Kessler S. A., Shimosato-Asano H., et al. (2010). PAMP (pathogen-associated molecular pattern)-induced changes in plasma membrane compartmentalization reveal novel components of plant immunity. J. Biol. Chem 285 39140–39149. 10.1074/jbc.M110.160531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinboelting N., Huep G., Kloetgen A., Viehoever P., Weisshaar B. (2012). GABI-Kat SimpleSearch: new features of the Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA mutant database. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 D1211–D1215. 10.1093/nar/gkr1047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobae Y., Uemura T., Sato M. H., Ohnishi M., Mimura T., Nakagawa T., et al. (2004). Zinc transporter of Arabidopsis thaliana AtMTP1 is localized to vacuolar membranes and implicated in zinc homeostasis. Plant Cell Physiol. 45 1749–1758. 10.1093/pcp/pci015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohorn B. D., Kobayashi M., Johansen S., Friedman H. P., Fischer A., Byers N. (2006). Wall-associated kinase 1 (WAK1) is crosslinked in endomembranes, and transport to the cell surface requires correct cell-wall synthesis. J. Cell Sci. 119 2282–2290. 10.1242/jcs.02968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konlechner C., Turktas M., Langer I., Vaculik M., Wenzel W. W., Puschenreiter M., et al. (2013). Expression of zinc and cadmium responsive genes in leaves of willow (Salix caprea L.) genotypes with different accumulation characteristics. Environ. Pollut. 178 121–127. 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.02.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzesłowska M. (2011). The cell wall in plant cell response to trace metals: polysaccharide remodeling and its role in defense strategy. Acta Physiol. Plant. 33 35–51. 10.1007/s11738-010-0581-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lally D., Ingmire P., Tong H. Y., He Z. H. (2001). Antisense expression of a cell wall-associated protein kinase, WAK4, inhibits cell elongation and alters morphology. Plant Cell 13 1317–1331. 10.1105/tpc.13.6.1317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merz D., Richter J., Gonneau M., Sanchez-Rodriguez C., Eder T., Sormani R., et al. (2017). T-DNA alleles of the receptor kinase THESEUS1 with opposing effects on cell wall integrity signaling. J. Exp. Bot. 10.1093/jxb/erx263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meychik N. R., Nikolaeva Y. I., Komarynets O. V., Ermakov I. P. (2011). Barrier function of the cell wall during uptake of nickel ions. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 58 409–414. 10.1134/S1021443711030137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki S., Murata T., Sakurai-Ozato N., Kubo M., Demura T., Fukuda H., et al. (2009). ANXUR1 and 2, sister genes to FERONIA/SIRENE, are male factors for coordinated fertilization. Curr. Biol. 19 1327–1331. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T., Skoog F. (1962). A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 15 473–497. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muschitz A., Riou C., Mollet J. C., Gloaguen V., Faugeron C. (2015). Modifications of cell wall pectin in tomato cell suspension in response to cadmium and zinc. Acta Physiol. Plant. 37:245 10.1007/s11738-015-22792000-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen K. S., Willats W. G. T., Malinovsky F. G. (2016). Understanding CrRLK1L function: cell walls and growth control. Trends Plant Sci. 21 516–527. 10.1016/j.tplants.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrotta L., Guerriero G., Sergeant K., Cai G., Hausman J.-F. (2015). Target or barrier? The cell wall of early- and later- diverging plants vs cadmium toxicity: differences in the response mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 6:133 10.3389/fpls.2015.00133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paynel F., Schaumann A., Arkoun M., Douchiche O., Morvan C. (2009). Temporal regulation of cell-wall pectin methylesterase and peroxidase isoforms in cadmium-treated flax hypocotyl. Ann. Bot. 104 1363–1372. 10.1093/aob/mcp254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelloux J., Rustérucci C., Mellerowicz E. J. (2007). New insights into pectin methylesterase structure and function. Trends Plant Sci. 12 267–277. 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieu I., Powers S. J. (2009). Real-time quantitative RT-PCR: design, calculations, and statistics. Plant Cell 21 1031–1033. 10.1105/tpc.109.066001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schallus T., Jaeckh C., Fehér K., Palma A. S., Liu Y., Simpson J. C., et al. (2008). Malectin: a novel carbohydrate-binding protein of the endoplasmic reticulum and a candidate player in the early steps of protein N-glycosylation. Mol. Biol. Cell 19 3404–3414. 10.1091/mbc.E08-04-0354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessions A., Burke E., Presting G., Aux G., McElver J., Patton D., et al. (2002). A high-throughput Arabidopsis reverse genetics system. Plant Cell 14 2985–2994. 10.1105/tpc.004630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih H.-W., Miller N. D., Dai C., Spalding E. P., Monshausen G. B. (2014). The receptor-like kinase FERONIA is required for mechanical signal transduction in Arabidopsis seedlings. Curr. Biol. 24 1887–1892. 10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S., Parihar P., Singh R., Singh V. P., Prasad S. M. (2016). Heavy metal tolerance in plants: role of transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and ionomics. Front. Plant Sci. 6:1143 10.3389/fpls.2015.01143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stegmann M., Monaghan J., Smakowska-Luzan E., Rovenich H., Lehner A., Holton N., et al. (2017). The receptor kinase FER is a RALF-regulated scaffold controlling plant immune signaling. Science 355 287–289. 10.1126/science.aal2541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennstedt P., Peisker D., Böttcher C., Trampczynska A., Clemens S. (2009). Phytochelatin synthesis is essential for the detoxification of excess zinc and contributes significantly to the accumulation of zinc. Plant Physiol. 149 938–948. 10.1104/pp.108.127472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voxeur A., Höfte H. (2016). Cell wall integrity signaling in plants: “To grow or not to grow that’s the question”. Glycobiology 26 950–960. 10.1093/glycob/cww029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner T. A., Kohorn B. D. (2001). Wall-associated kinases are expressed throughout plant development and are required for cell expansion. Plant Cell 13 303–318. 10.1105/tpc.13.2.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber M., Deinlein U., Fischer S., Rogowski M., Geimer S., Tenhaken R., et al. (2013). A mutation in the Arabidopsis thaliana cell wall biosynthesis gene pectin methylesterase 3 as well as its aberrant expression cause hypersensitivity specifically to Zn. Plant J. 76 151–164. 10.1111/tpj.12279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S., Hématy K., Höfte H. (2012). Growth control and cell wall signaling in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63 381–407. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf S., Höfte H. (2014). Growth control: a saga of cell walls, ROS, and peptide receptors. Plant Cell 26 1848–1856. 10.1105/tpc.114.125518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S.-L., Rahman A., Baskin T. I., Kieber J. J. (2008). Two leucine-rich repeat receptor kinases mediate signaling, linking cell wall biosynthesis and ACC synthase in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20 3065–3079. 10.1105/tpc.108.063354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X. Y., Zeng Z. H., Yan J. Y., Fan W., Bian H. W., Zhu M. Y., et al. (2013). Association of specific pectin methylesterases with?Al-induced root elongation inhibition in rice. Physiol. Plant. 148 502–511. 10.1111/ppl.12005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F., Li J., Huang Y., Liu L., Li D., Chen L., et al. (2014). FERONIA receptor kinase controls seed size in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 7 920–922. 10.1093/mp/ssu010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F., Qian L., Nibau C., Duan Q., Kita D., Levasseur K., et al. (2012). FERONIA receptor kinase pathway suppresses abscisic acid signaling in Arabidopsis by activating ABI2 phosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 14693–14698. 10.1073/pnas.1212547109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.