Abstract

Background

Social media is a popular online tool that allows users to communicate and exchange information. It allows digital content such as pictures, videos and websites to be shared, discussed, republished and endorsed by its users, their friends and businesses. Adverts can be posted and promoted to specific target audiences by demographics such as region, age or gender. Recruiting for health research is complex with strict requirement criteria imposed on the participants. Traditional research recruitment relies on flyers, newspaper adverts, radio and television broadcasts, letters, emails, website listings, and word of mouth. These methods are potentially poor at recruiting hard to reach demographics, can be slow and expensive. Recruitment via social media, in particular Facebook, may be faster and cheaper.

Objective

The aim of this study was to systematically review the literature regarding the current use and success of Facebook to recruit participants for health research purposes.

Methods

A literature review was completed in March 2017 in the English language using MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, PubMed, PsycInfo, Google Scholar, and a hand search of article references. Papers from the past 12 years were included and number of participants, recruitment period, number of impressions, cost per click or participant, and conversion rate extracted.

Results

A total of 35 studies were identified from the United States (n=22), Australia (n=9), Canada (n=2), Japan (n=1), and Germany (n=1) and appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist. All focused on the feasibility of recruitment via Facebook, with some (n=10) also testing interventions, such as smoking cessation and depression reduction. Most recruited young age groups (16-24 years), with the remaining targeting specific demographics, for example, military veterans. Information from the 35 studies was analyzed with median values being 264 recruited participants, a 3-month recruitment period, 3.3 million impressions, cost per click of US $0.51, conversion rate of 4% (range 0.06-29.50), eligibility of 61% (range 17-100), and cost per participant of US $14.41. The studies showed success in penetrating hard to reach populations, finding the results representative of their control or comparison demographic, except for an over representation of young white women.

Conclusions

There is growing evidence to suggest that Facebook is a useful recruitment tool and its use, therefore, should be considered when implementing future health research. When compared with traditional recruitment methods (print, radio, television, and email), benefits include reduced costs, shorter recruitment periods, better representation, and improved participant selection in young and hard to reach demographics. It however, remains limited by Internet access and the over representation of young white women. Future studies should recruit across all ages and explore recruitment via other forms of social media.

Keywords: epidemiology, social media, review, research

Introduction

Social media is a popular Web-based tool that allows users to communicate and exchange information [1]. It allows digital content such as pictures, videos, and websites to be shared, discussed, republished, and endorsed by its users, their friends, and businesses. Adverts can be posted and promoted to specific target audiences by demographics such as region, age, or gender.

Social media has grown tremendously with Facebook, increasing from 6m to 1bn daily users from 2005 to 2015 [2]. This visibility lead to most social media sites monetizing adverts, with 92% of the private sector currently using social media as one of their employee recruitment strategies [3]. In 2014, 66% of the UK population used social media, with 96% of those users choosing Facebook [4]. It continued to grow in 2016, with 72% of the population using social media and 97% of them choosing Facebook [1].

Recruiting for health research is complex with strict requirement criteria imposed on the participants. Traditional research recruitment relies on flyers, newspaper adverts, radio and television broadcasts, letters, emails, website listings, and word of mouth. These methods are potentially poor at recruiting hard to reach demographics, can be slow, and expensive [5,6]. Recruitment via social media, in particular Facebook, may be faster and cheaper.

This paper aims to summarize the available evidence regarding Facebook as a recruitment tool for health research in terms of cost, speed, and its ability to find and represent hard to reach demographic groups (see Table 1 for common definitions). It will be compared with traditional methods and deemed successful if it shows equal or better costing and representation of target demographics. This will be the first systematic review the authors are aware of to summarize and appraise this data.

Table 1.

Common definitions.

| Impressions | The number of times that the ad is fetched (starts downloading to a computer or device) |

| Cost per click | The cost of advertising divided by the number of times the advert is clicked shown in USD ($) |

| Conversion rate | The number of people who click on the ad and then proceed to become paying customers, or in the case of research, participants (considered before their eligibility) |

| Eligibility | The percentage of participants who respond and are eligible for the trial. This reflects the specificity of ad campaigns targeting |

| Cost per participant | The cost of advertising divided by the eligible recruited participants |

Methods

A search of six databases, namely MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, PubMed, PsycInfo, Google Scholar, and an additional hand search of reference lists was performed in March 2017. It spanned the past 12 years due to the rise of social media from a negligible entity in 2006. A combination of the following keywords was implemented as a search strategy looking within the title or abstract:

Facebook, social media*, social network* AND internet, online, web* AND recruit*, research*, volunteer*, participant*, respondent*, patient select*, stud*, epidemiology, clinical*, health communication*, survey*

All the papers identified were exported to RefWorks [7], and duplicates were removed. Subsequently, the following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) Non-English language; (2) those not using Facebook as the recruitment tool; (3) those not recruiting for health research purposes; (4) those not constituting original research; (5) conference proceedings, letters to editors, posters, comments, and dissertations (due to difficulty accessing the full text and probable lack of detail); and (6) systematic reviews (although their reference lists were examined for eligible papers).

Full papers were appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist [8], and those deemed invalid were excluded (scoring less than 7/9; see Multimedia Appendix 1). Results tabulated included target demographic, number recruited, recruitment length, impressions, cost per ad click, conversion rate, eligibility, and cost per participant. Data was exported to Microsoft Excel for statistical analysis. Major outliers were removed (outside three standard deviations [SDs]), after which mean, median, and interquartile range were calculated.

Results

Summary of Accepted Studies

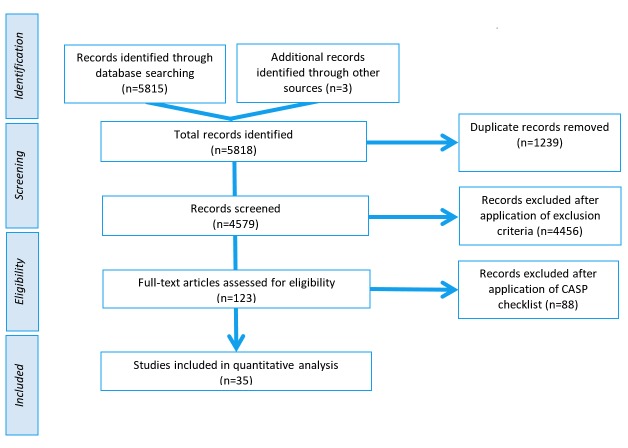

A total of 5818 records were identified during the initial searches. Duplicates were removed (n=1239) and 4579 records were screened against the exclusion criteria (Figure 1). Additionally, 123 full papers were assessed for quality using the study design specific CASP checklist revealing 35 papers (scoring 7-9/9) to be included in the review (see Multimedia Appendix 1). Quantitative and qualitative data was tabulated (Tables 2 and 3), allowing comparison of cost and demographic recruited.

Figure 1.

Article selection diagram.

Table 2.

Extracted quantitative data from the 35 included papers.

| Author | Number recruited |

Recruitment length (months)a |

Impressions (millions) |

Cost per ad click (US $)b | Conversion rate (%), n numbers included where available |

Eligibility (%), n numbers included where available |

Cost per participant (US $)b |

| Adam LM (2016) [15] | 45 | 0.8 | 0.04 | 0.21b | NRc | 56 (n=45) | 15.12b |

| Admon L (2016) [29] | 1178 | 1.0 | 0.36 | 0.58 | 13.2 (n=1592) | 74 (n=1178) | 14.63 |

| Akard TF (2015) [17] | 106 | 2.0 | 3.90 | 1.08 | 3.0 | 61 (n=106) | 17 |

| Arcia, A (2014) [18] | 344 | 4.0 | 10.50 | 0.63 | 6.0 | 50 | 11.11 |

| Batterham PJ (2014) [28] stage 1 |

610 | 0.1 | NR | NR | 3.0 | NR | 9.82b |

| Batterham PJ (2014) [28] stage 2 |

1283 | 0.1 | NR | NR | 3.0 | NR | 1.51b |

| Bauermeister JA (2012) [30] | 22 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Bull S (2013) [31] | 1578 | 36.0d | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Carlini B (2015) [19] | 285 | 4.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 8.92 |

| Carter-Harris L (2016) [9] | 331 | 0.6 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 29.5 | NR | 1.51 |

| Child RJH (2014) [20] | 78 | 0.1 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Chu JL (2013) [21] | 88 | 9.0 | 17.50 | 0.39b | 5.0 (n=180) | 49 | 15.35b |

| Close S (2013) [22] | 39 | 0.2 | 2.50 | 0.61 | 18.0 | NR | 19.44 |

| Crosier BS (2016) [32] | 264 | 1.0 | 0.01 | 0.20 | NR | NR | 8.14 |

| Fenner Y (2012) [33] | 278 | 4.0 | 36.10 | 0.48b | 4.0 | NR | 14.50b |

| Frandsen TL (2014) [6] | 138 | 19.0 | 14.50 | 0.68b | NR | NR | 30.48b |

| Frandsen M (2016) [10] | 92 | 13.5 | NR | NR | NR | 61 | 74.64b |

| Harris ML (2015) [34] | NR | 8.0 | NR | 0.51b | 2.0 | 93 (n=3795) | 8.55b |

| Jones R (2015) [35] | 230 | 1.0 | NR | 0.36 | 3.0 | 39 | 37.74 |

| Kappa JM (2013) [36] | 0 | 0.3 | 0.90 | 0.98 | 3.0 | 78 (n=280) | NR |

| Miyagi E (2014) [37] | 126 | 9.0 | 5.70 | NR | NR | 95 | NR |

| Moreno MA (2017) [14] | 8 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 40.99 |

| Morgan AJ (2015) [16] | 35 | 11.0 | 2.00 | 0.45b | NR | NR | 14.32b |

| Musiat P (2016) [38] | 26 | 3.0 | 0.50 | 1.74b,d | 0.1 | 90 | 76.15b |

| Nelson EJ (2014) [24] | 1003 | 2.0 | NR | NR | 48.0d(n=1003) | 91 | 1.36 |

| Parkinson S (2013) [39] | 100 | 0.2 | 1.30 | NR | 15.0 | 83 | NR |

| Pedersen ER (2014) [25] | 1023 | 1.0 | 3.30 | 0.38 | 5.0 | 45 | 7.05 |

| Ramo DE (2014) [40] | 1548 | 13.0 | 28.70 | 0.45 | 1.0 | NR | 4.28 |

| Ramo DE (2012) [41] | 230 | 2.0 | 3.20 | 0.34 | 9.0 | 51 | 8.80 |

| Raviotta JM (2016) [11] | 428 | 6.0 | 21.00 | 1.24 | NR | NR | 110.00d |

| Remschmidt C (2014) [42] | 1161 | 2.0 | 62.90 | NR | 9.0 | NR | NR |

| Schumacher KR (2014) [26] | 394 | 12.0 | NR | NR | NR | 100 (n=394) | NR |

| Schwinn T (2017) [43] | 797 | 4.2 | 187.00d | 0.6 | 2.8 | 43 (n=1873) | 51.70 |

| Staffileno BA (2016) [13] | 23 | 18.0 | NR | 0.73 | NR | 17 | NR |

| Subasinghe AK (2016) [12] | 919 | 13.0 | 55.40 | 0.67b | NR | NR | 17.29b |

| Yuan P (2014) [27] | 1404 | 4.0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 3.56 |

aCalculated as a percentage of a 31-day month.

bAUD converted to USD with 0.72 and CD to USD with 0.75 exchange rates where appropriate.

cNR: not reported; not reported if data unavailable.

dOutliers of over 3 standard deviations excluded from statistical calculation.

Table 3.

Extracted qualitative data (Authors G-Z) from the 35 included papers.

| Author | Country | Target demographica | Comparison to control demographic |

| Harris ML (2015) [34] | Australia | 18-23 years | Partly representative; higher proportion of female and tertiary education |

| Jones R (2015) [23] | United States | 18-29 years, female, in a sexual relationship with at least one man in past 3 months | Partly representative; higher proportion of education |

| Kappa JM (2013) [36] | United States | 35-49 years, female | No comparison made |

| Miyagi E (2014) [37] | Japan | 16-35 years, female | Partly representative; higher proportion of 26-35 age group and a low BMIb, and lower proportion of 16-21 age group |

| Moreno MA (2017) [14] | United States | 14-18 years | No comparison made |

| Morgan AJ (2015) [16] | Australia | No other criteria | No comparison made |

| Musiat P (2016) [38] | Australia | 18-25 years | No comparison made |

| Nelson EJ (2014) [24] | United States | 18-30 years, lives in metropolitan area | Partly representative; higher proportion of HPVcvaccination |

| Parkinson S (2013) [39] | Australia | 18-25 years | Partly representative; higher proportion of females, university education, unemployed and high income rate, and lower proportion of full time employment |

| Pedersen ER (2014) [25] | United States | 18-34 years, previously served in the US Air Force, Army, Marine Corps, Navy | Partly representative; higher proportion of Hispanic or Latino and lower proportion of black or African American |

| Ramo DE (2014) [40] | United States | 18-25 years, smoker | Partly representative; higher proportion of white and males |

| Ramo DE (2012) [41] | United States | 18-25 years | Partly representative; higher proportion of white and males |

| Raviotta JM (2016) [11] | United States | 18-25, male, student, lives in Pittsburgh | Partly representative; higher proportion of homo or bisexual and social media use |

| Remschmidt C (2014) [42] | Germany | 18-25 years | Representative |

| Schumacher KR (2014) [26] | United States | 15-18 years, parents of <15 years, Fontan-associated protein losing enteropathy, plastic bronchitis | Representative |

| Schwinn T (2017) [43] | United States | 13-14 years, female | Partly representative; higher proportion of African American and less reported parents completing high school. Smoking, drinking, and drugs use was representative |

| Staffileno BA (2016) [13] | United States | 18-45 years, prehypertension | No comparison made |

| Subasinghe AK (2016) [12] | Australia | 18-25 years, in Victoria who had not been vaccinated against HPV | Representative |

| Yuan P (2014) [27] | United States | HIVdpositive | No comparison made |

aAssume all are over 18 years and English speaking unless otherwise stated.

bBMI: body mass index.

cHPV: human papillomavirus.

dHIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

Most studies were conducted in the United States (n=22) with some in Australia (n=9) and Canada (n=2) and one in Japan and Germany, respectively. Some studies also tested interventions (n=10); three recruited for smoking cessation [6,9,10], two for human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination [11,12], two for healthier lifestyle intervention [13,14]; and one each for perinatal studies [15], human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention via soap opera viewing [3], and depression intervention [16]. Ten papers recruited those aged 18 years and over, 7 the age group of 18-25 years, and 16 recruited different ages (See Tables 3 and 4 for more demographic information).

Table 4.

Extracted qualitative data (authors A-F) from the 35 included papers.

| Author | Country | Target demographica | Comparison with control demographic |

| Adam LM (2016) [15] | Canada | 23-40 years, female, <25 miles from center, 8-20 weeks pregnant | No comparison made |

| Admon L (2016) [29] | United States | African American or Hispanic interested in pregnancy | Partly representative; higher proportion of African Americans, high income, pregnancy, and reporting fair or poor health |

| Akard TF (2015) [17] | United States | Parents of children or teenagers | Partly representative; higher proportion of white and female |

| Arcia, A (2014) [18] | United States | 18-44 years, nulliparous, >20 weeks gestation | Partly representative; higher proportion of younger age groups |

| Batterham PJ (2014) [28] stage 1 |

Australia | No other criteria | Partly representative; higher proportion of education, females, young adults, and lower levels of young adolescents |

| Batterham PJ (2014) [28] stage 2 |

Australia | No other criteria | No comparison made |

| Bauermeister JA (2012) [30] | United States | 18-24 years | Partly representative; higher proportion of white ethnicity and tertiary education and lower proportion of cigarette use |

| Bull S (2013) [31] | United States | 15-24 years | Representative |

| Carlini B (2015) [19] | United States | Brazilian and Portuguese speakers | No comparison made |

| Carter-Harris L (2016) [9] | United States | 55-77 years, current or ex-smokers | No comparison made |

| Child RJH (2014) [20] | United States | Emergency nurses | Representative |

| Chu JL (2013) [21] | Canada | 15-24 years, PTSDb | Partly representative; higher proportion of females and younger adults |

| Close S (2013) [22] | United States | Any age, Klinefelter syndrome | Representative |

| Crosier BS (2016) [32] | United States | Self-reports auditory hallucinations | Partly representative; higher proportion females |

| Fenner Y (2012) [33] | Australia | 16-25 years, female | Partly representative; higher proportion of increased BMIc |

| Frandsen TL (2014) [6] | Australia | Smoking >10 cigarettes per day for 3+ years, not enrolled in a cessation trial in the last 3 months | Partly representative; higher proportion of young adults |

| Frandsen M (2016) [10] | Australia | Smokers 10+ per day, 3 years +, no intention to quit next month, >25km from city center | No comparison made |

aAssume all are over 18 years and English speaking unless otherwise stated.

bPTSD post-traumatic stress disorder.

cBMI: body mass index.

Other than basic demographic information including age and sex, most papers recruited participants with specific characteristics (n=18), including parents of children [17], nulliparous women at the beginning of their pregnancy [18], Brazilian and Portuguese speakers [19], emergency nurses [20], those with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [21], those with Klinefilter syndrome [22], those in sexual relationships [23], those living in a metropolitan area [24], US veterans [25], parents of children with Fontan-associated protein losing enteropathy [26], and those of positive HIV status [27]. Two papers [16,28] had no targeting features except being over 18 years old.

Summary of Quantitative Data

There were several pieces of data that outlay three SDs and so were removed from statistical analysis, namely, a recruitment length of 36 months [31], an impression count of 127 million [43], a cost per click of US $1.74 [38], a conversion rate of 48% [24], and a cost per participant of US $110.00 [11].

Table 5 shows median data: 264 recruited participants, a 3-month recruitment period, 3.3 million impressions, cost per click of US $0.51, conversion rate of 4% (range 0.06-29.50), eligibility of 61% (range 17-100), and cost per participant of US $14.41.

Table 5.

Statistical analysis of extracted data with outliers removed.

| Form of distribution analysis | Number recruited |

Recruitment length (months) |

Impressions (millions) |

Cost per ad click (US $) |

Conversion rate (%) | Eligibility (%) | Cost per participant (US $) |

| Mean | 463 | 5.13 | 12.9 | 0.57 | 7 | 65 | 19.77 |

| Median | 264 | 3.00 | 3.3 | 0.51 | 4 | 61 | 14.41 |

| Interquartile range | 775 | 8.00 | 16.6 | 0.28 | 6 | 39 | 10.66 |

Target Population

Most studies (n=24) compared their recruited participants with either a control group recruited by traditional methods or to national data. This showed the recruited participants to be relatively representative except for some minor differences:

There was over representation of females in 5 papers [17,21,28,32,39] and of males in 2 papers [40,41].

Four papers reported an over representation of white ethnicity [17,30,40,41], two of African American representation [29,43], and 1 an over representation of Hispanic or Latino ethnicities [25].

Four papers suggested over representation of a young adult group [9,18,21,28], including Frandsen M (2014), who found Web-based age to be significant younger than from the control groups recruited by mail, newspaper ads, and flyers.

Four papers reported a higher degree of education [23,30,34,39] and two a higher rate of income [29,39] than that of the general population.

Fenner Y (2012) reported an over representation of people with a higher body mass index (BMI) in Australia [33], whereas Miyagi, E (2014) reported an over representation of low BMI in Japan [37].

Nelson EJ (2014) reported a higher rate of HPV vaccination [24] than predicted in Australia, whereas Remschmidt C (2014) shows it to be representative of the general population in Germany [42].

Bauermeister JA (2012) showed the participants to be representative of the general population for alcohol consumption, marijuana, ecstasy, and cocaine use [30], with Jones R (2012) showing representation of marijuana use, sexually transmitted infection (STI) rates, and sexual relationship history [35].

Full time employment [25] and nonsmoker status [30] where each under represented once compared with the general population.

Discussion

This paper summarizes the available evidence regarding the success of Facebook as a recruitment tool for research purposes. Some of the results can only be compared with Web-based advertising, namely, the impressions, cost per click, and conversion rate as traditional recruitment uses different markers. The remaining data on recruitment number, length of study, eligibility, and cost per participant can be compared widely with other forms of traditional recruitment.

Facebook Compared With Web-Based Advertising

Cost per click only varied slightly across studies, especially when targeting similar groups. The median cost per click from this review was US $0.51 compared with US $0.27—the mean cost per click on Facebook as a whole [44]. This shows people are less likely to interact with a health recruitment ad. The conversion rate of 4% can also be compared with the mean value of 2.4% across all Web-based advertising [45]. This suggests that although people are less interested in health research ads overall, those who do interact with them are more likely to convert. This increase in conversion rate however, doesn’t appear large enough to counteract the increased cost per click with health recruitment still costing more than general advertising.

Facebook Compared With Traditional Methods

The cost per participant on Facebook was shown to be less than traditional methods. Our median value of US $14.41 compares favorably with rates suggested by Tate, D (2014) of US $1094.27 per participant for television recruitment, US $811.99 for printed media, US $635.92 for radio, and US $37.77 for email when recruiting for a survey on English language competency [5]. Carlini BH (2015) had similar findings with a mean cost per participant of US $16.22 via Google ads, and between US $13.12 and US $250.00 for other traditional methods when recruiting young adults for weight gain analysis [19].

The cost per participant values contained a major outlier; Raviotta JM (2016) reported a cost of US $110 per recruited participant [11]. The cost per click of the study (US $1.24) fell slightly outside one SD of the median and did not explain the increased cost per participant. On closer inspection, the reason for the expense became clear, “the difference in time and effort required to complete a 7-13 month study with two blood draws and three vaccine injections vs. a 30 minute survey...explains the increased cost” [11].

Facebook Compared With Other Social Media Sites

Three articles simultaneously used other social media sites to recruit participants, namely Twitter and MySpace. Bull S (2013) used MySpace but found it unsuccessful in recruiting any participants [31]. This is unsurprising considering the massive drop in MySpace primary users from 2008 to 2011 [46]. Harris, M. L (2015) implemented recruitment via Facebook and Twitter but changed to use Facebook alone due to its increased success [34]. Yuan P (2014) also used Twitter alongside Facebook. The study received 10,006 Facebook ad clicks and 161 Twitter interactions. It was found that the number of Facebook ad clicks was moderately correlated to the number recruited (r=.52 P<.001) but that there was little correlation between Twitter interactions and links clicked (r=.17, P=.06; r=.18, P=.06, respectively) [27]. These findings suggest Facebook is a superior recruitment tool when compared with Twitter and MySpace, although there is limited analysis across the three papers. This was an interesting albeit unintentional finding, but more research should be carried out in this area before making conclusions.

Facebook’s Representation of the Population

Sociodemographic characteristics of the recruited participants were compared either with traditionally recruited participants or to available national statistics. Alcohol consumption; marijuana, ecstasy, and cocaine use [30]; STI rates; and sexual relationship history [35] were found to be representative of the total population. Those who use recreational drugs and have at risk sexual behavior tend to be found in hard to reach populations. The fact these studies mirror national statistics highlights the power of social media to target specific populations. Traditional methods tend to under represent these groups [47], meaning Facebook recruitment potentially yields more significant results.

Another point highlighting the success of Facebook recruitment would be the differing BMI results from Miyagi E (2014) and Fenner Y (2012), with the latter Australian paper showing a considerably higher average than the Japanese study. This simply shows the different obesity rates of the two countries. Australia reports 64% of its population to have a BMI above 25kg/m2compared with 24% in Japan [48]. This also seems true for the differences in reported rates of HPV vaccination between Nelson EJ (2014) and Remschmidt C (2014); 39.7% of adolescent females in America [49] are vaccinated compared with 49% of Germans [50].

Other demographic data was found to be representative of the target population and comparable with traditional recruitment with only a few exceptions:

There was an over representation of white ethnicity. Facebook claims to be diverse [51], but papers suggest either these claims are not true, targeted marketing misses certain ethnicities, or that different groups have different response rates. This over representation is also shown in a review of traditional methods by Yancey AK (2005), suggesting the problem is not limited to social media recruitment [52].

Four papers also showed over representation of females. This may be due to the fact that a higher percentage of women use Facebook [1] or because fewer men respond to recruitment in general [53]. Brown WJ (1998) found similar results using traditional methods, again suggesting the problem is not limited to Facebook [54].

Education and income are often confounding factors, and it is perhaps unsurprising to find over representation in both these areas. This is comparable again with traditional recruitment methods, with Gorelick PB (1998) finding that more years in education increased the likelihood of entering and completing a clinical trial with those of lower levels “not wanting to be guinea pigs” [55].

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this review include the wide search ensuring all available literature was gathered and the detailed cost analysis. The main limitation is the relatively small number of studies available with numerical data on costings and population comparisons. Several papers had substantial recruitment numbers (n=1578 [30), but many were small (n=26 [13]), reducing the reliability. Most papers focused on ages in the range of 18-30 years. Carter-Harris L (2016) [9] recruited those aged 55-77 years, showing that although older people may be less likely to adopt newer technologies (of those over 65 years, 48% are active Facebook users compared with 64% for 50-64 year olds, 79% for 30-49 year olds, and 82% for 18-29 year olds [56]), recruitment can still be successful, reporting US $1.51 cost per participant. The expected barrier from lack of Internet access or experience in the older population is smaller than most think.

The percentage of people with access to the Internet is steadily increasing [1], and procedural methods can be put into place to prevent this misrepresentation of data [57]. Young, SD (2013) found that even 79% of homeless youths manage to access social media sites once per week [58]. Although Internet access currently remains to be a barrier, it seems to be smaller than barriers facing traditional methods and is set to improve in the future.

Conclusions

There is growing evidence to suggest that Facebook is a successful recruitment tool, and its use, therefore, should be considered when implementing future health research. Benefits include reduced cost, shorter recruitment periods, better representation, and improved participant selection in young and hard to reach demographics. This may spell the end for traditional methods, although currently the minor limitations of Internet access and the over representation of young white women may make its use inappropriate in some settings.

Abbreviations

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- HPV

human papillomavirus

- PTSD

post-traumatic stress disorder

Cohort study CASP checklist scores – score out of first 9 questions.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Ofcom. 2015. [2017-07-29]. Adults’ media use and attitudes: report 2015 https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/82112/2015_adults_media_use_and_attitudes_report.pdf .

- 2.Fb. 2015. [2016-10-24]. Company info http://newsroom.fb.com/company-info .

- 3.Johnson K, Mueller N, Gutmann D. Abstract 4847: efficacy of different recruitment methods for a neurofibromatosis type 1 online registry. Cancer Res. 2014 Nov 18;73(8 Supplement):4847–7. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2013-4847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ofcom. 2015. [2016-10-24]. Adults media use and attitudes 2014 http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/market-data-research/other/research-publications/adults/adults-media-lit-14/

- 5.Tate DF, LaRose JG, Griffin LP, Erickson KE, Robichaud EF, Perdue L, Espeland MA, Wing RR. Recruitment of young adults into a randomized controlled trial of weight gain prevention: message development, methods, and cost. Trials. 2014;15:326. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-326. http://www.trialsjournal.com/content/15//326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frandsen M, Walters J, Ferguson SG. Exploring the viability of using online social media advertising as a recruitment method for smoking cessation clinical trials. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014 Feb;16(2):247–51. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Refworks. 2015. [2016-10-24]. Want to learn how to get the most out of RefWorks? https://www.refworks.com/refworks2/default.aspx?r=authentication::init .

- 8.Wix. 2017. [2017-07-29]. 12 questions to help you make sense of cohort study http://media.wix.com/ugd/dded87_5ad0ece77a3f4fc9bcd3665a7d1fa91f.pdf .

- 9.Bradshaw RA, Walsh KA, Neurath H. Amino acid sequence of bovine carboxypeptidase A. Isolation and characterization of selected peptic and nagarse peptides and the complete sequence of fragment F-I. Biochemistry. 1971 Mar 16;10(6):961–72. doi: 10.1021/bi00782a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dausset J. [The law of choice of an organ donor for transplantation] Arch Mal Coeur Vaiss. 1969 Jun;62(6):841–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heilmann E, Müller KM, Westerloh K, Manz B. [Clinical picture of acute intermittent porphyria with reference to morphological findings] Med Welt. 1974 Sep 27;25(39):1538–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collins TF. Ambulatory treatment of active pulmonary tuberculosis without interruption of normal employment. S Afr Med J. 1969 Jan 18;43(3):58–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staffileno BA, Zschunke J, Weber M, Gross LE, Fogg L, Tangney CC. The feasibility of using facebook, craigslist, and other online strategies to recruit young African American women for a web-based healthy lifestyle behavior change intervention. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;32(4):365–71. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreno MA, Waite A, Pumper M, Colburn T, Holm M, Mendoza J. Recruiting adolescent research participants: in-person compared to social media approaches. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2017 Jan;20(1):64–7. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2016.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adam LM, Manca DP, Bell RC. Can facebook be used for research? experiences using facebook to recruit pregnant women for a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2016 Sep 21;18(9):e250. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6404. http://www.jmir.org/2016/9/e250/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgan AJ, Jorm AF, Mackinnon AJ. Internet-based recruitment to a depression prevention intervention: lessons from the Mood Memos study. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(2):e31. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2262. http://www.jmir.org/2013/2/e31/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akard TF, Wray S, Gilmer MJ. Facebook advertisements recruit parents of children with cancer for an online survey of web-based research preferences. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38(2):155–61. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000146. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24945264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arcia A. Facebook advertisements for inexpensive participant recruitment among women in early pregnancy. Health Educ Behav. 2013 Sep 30;41(3):237–41. doi: 10.1177/1090198113504414. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/24082026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlini BH, Safioti L, Rue TC, Miles L. Using Internet to recruit immigrants with language and culture barriers for tobacco and alcohol use screening: a study among Brazilians. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015 Apr;17(2):553–60. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9934-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Child RJH, Mentes JC, Pavlish C, Phillips LR. Using Facebook and participant information clips to recruit emergency nurses for research. Nurse Res. 2014 Jul;21(6):16–21. doi: 10.7748/nr.21.6.16.e1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu JL, Snider CE. Use of a social networking web site for recruiting Canadian youth for medical research. J Adolesc Health. 2013 Jun;52(6):792–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Close S, Smaldone A, Fennoy I, Reame N, Grey M. Using information technology and social networking for recruitment of research participants: experience from an exploratory study of pediatric Klinefelter syndrome. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(3):e48. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2286. http://www.jmir.org/2013/3/e48/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones R, Lacroix LJ, Nolte K. “Is Your Man Stepping Out?” an online pilot study to evaluate acceptability of a guide-enhanced HIV prevention soap opera video series and feasibility of recruitment by facebook advertising. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2015;26(4):368–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2015.01.004. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/26066692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson EJ, Hughes J, Oakes JM, Pankow JS, Kulasingam SL. Estimation of geographic variation in human papillomavirus vaccine uptake in men and women: an online survey using facebook recruitment. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(9):e198. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3506. http://www.jmir.org/2014/9/e198/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pedersen ER, Helmuth ED, Marshall GN, Schell TL, PunKay M, Kurz J. Using facebook to recruit young adult veterans: online mental health research. JMIR Res Protoc. 2015;4(2):e63. doi: 10.2196/resprot.3996. http://www.researchprotocols.org/2015/2/e63/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schumacher KR, Stringer KA, Donohue JE, Yu S, Shaver A, Caruthers RL, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Fifer C, Goldberg C, Russell MW. Social media methods for studying rare diseases. Pediatrics. 2014 May;133(5):e1345–53. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2966. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=24733869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yuan P, Bare MG, Johnson MO, Saberi P. Using online social media for recruitment of human immunodeficiency virus-positive participants: a cross-sectional survey. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(5):e117. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3229. http://www.jmir.org/2014/5/e117/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Batterham PJ. Recruitment of mental health survey participants using internet advertising: content, characteristics and cost effectiveness. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2014 Jun;23(2):184–91. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lusterman EA. The dental profession and the dental laboratory industry. N Y State Dent J. 1965 Dec;31(10):457–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA, Johns MM, Glowacki P, Stoddard S, Volz E. Innovative recruitment using online networks: lessons learned from an online study of alcohol and other drug use utilizing a web-based, respondent-driven sampling (webRDS) strategy. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012 Sep;73(5):834–8. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.834. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22846248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bull S, Levine D, Schmiege S, Santelli J. Recruitment and retention of youth for research using social media: experiences from the Just/Us study. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2013 Jun;8(2):171–81. doi: 10.1080/17450128.2012.748238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siegfried J. [Contribution of functional neurosurgery in the treatment of cerebral palsy patients] Rev Otoneuroophtalmol. 1970 Nov;42(7):412–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fenner Y, Garland SM, Moore EE, Jayasinghe Y, Fletcher A, Tabrizi SN, Gunasekaran B, Wark JD. Web-based recruiting for health research using a social networking site: an exploratory study. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(1):e20. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1978. http://www.jmir.org/2012/1/e20/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harris ML, Loxton D, Wigginton B, Lucke JC. Recruiting online: lessons from a longitudinal survey of contraception and pregnancy intentions of young australian women. Am J Epidemiol. 2015 Apr 15;181(10):737–46. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones L, Saksvig BI, Grieser M, Young DR. Recruiting adolescent girls into a follow-up study: benefits of using a social networking website. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012 Mar;33(2):268–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.10.011. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/22101207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kapp JM, Peters C, Oliver DP. Research recruitment using Facebook advertising: big potential, big challenges. J Cancer Educ. 2013 Mar;28(1):134–7. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0443-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miyagi E, Motoki Y, Asai-Sato M, Taguri M, Morita S, Hirahara F, Wark JD, Garland SM. Web-based recruiting for a survey on knowledge and awareness of cervical cancer prevention among young women living in Kanagawa prefecture, Japan. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014 Sep;24(7):1347–55. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000220. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25054449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Musiat P, Winsall M, Orlowski S, Antezana G, Schrader G, Battersby M, Bidargaddi N. Paid and unpaid online recruitment for health interventions in young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2016 Sep 20;59(6):662–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parkinson S, Bromfield L. Recruiting young adults to child maltreatment research through facebook: a feasibility study. Child Abuse Negl. 2013 Sep;37(9):716–20. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramo DE, Rodriguez TMS, Chavez K, Sommer MJ, Prochaska JJ. Facebook recruitment of young adult smokers for a cessation trial: methods, metrics, and lessons learned. Internet Interv. 2014 Apr;1(2):58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramo DE, Prochaska JJ. Broad reach and targeted recruitment using Facebook for an online survey of young adult substance use. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(1):e28. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1878. http://www.jmir.org/2012/1/e28/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Remschmidt C, Walter D, Schmich P, Wetzstein M, Deleré Y, Wichmann O. Knowledge, attitude, and uptake related to human papillomavirus vaccination among young women in Germany recruited via a social media site. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(9):2527–35. doi: 10.4161/21645515.2014.970920. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/25483492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwinn T, Hopkins J, Schinke SP, Liu X. Using Facebook ads with traditional paper mailings to recruit adolescent girls for a clinical trial. Addict Behav. 2017 Feb;65:207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith C. Expandedramblings. 2015. [2016-10-24]. By the numbers+ amazing facebook advertising statistics http://expandedramblings.com/index.php/facebook-advertising-statistics/

- 45.Kim L. Searchengineland. 2015. [2016-10-24]. 7 conversion rate truths that will change your landing page strategy http://searchengineland.com/7-conversion-rate-truths-will-change-landing-page-optimization-strategy-191083 .

- 46.Wagner DA. Child development research and the third world. A future of mutual interest? Am Psychol. 1986 Mar;41(3):298–301. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.41.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dreyer K. Comscore. [2017-07-29]. Infographic: myspace vs facebook https://www.comscore.com/Insights/Data-Mine/Infographic-Myspace-vs-Facebook?cs_edgescape_cc=US .

- 48.WHO. [2017-07-29]. Global health observatory (GHO) data http://www.who.int/gho/en/

- 49.Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, Jeyarajah J, Singleton JA, Curtis RC, MacNeil J, Hariri S, Immunization Services Division‚ National Center for ImmunizationRespiratory Diseases. Centers for Disease ControlPrevention (CDC) National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years--United States, 2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014 Jul 25;63(29):625–33. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6329a4.htm. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Comporti M. Lipid peroxidation and cellular damage in toxic liver injury. Lab Invest. 1985 Dec;53(6):599–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marlow C. Cameronmarlow. [2017-07-29]. ePluribus: ethnicity on social networks http://cameronmarlow.com/media/chang-ethnicity-on-social-networks_0.pdf .

- 52.Yancey AK, Ortega AN, Kumanyika SK. Effective recruitment and retention of minority research participants. Annu Rev Public Health. 2006;27:1–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith W. Ed.gov. [2017-07-29]. Does gender influence online survey participation? a record-linkage analysis of university faculty online survey response behavior https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED501717 .

- 54.Brown WJ, Bryson L, Byles JE, Dobson AJ, Lee C, Mishra G, Schofield M. Women's health Australia: recruitment for a national longitudinal cohort study. Women Health. 1998;28(1):23–40. doi: 10.1300/j013v28n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gorelick PB, Harris Y, Burnett B, Bonecutter FJ. The recruitment triangle: reasons why African Americans enroll, refuse to enroll, or voluntarily withdraw from a clinical trial. An interim report from the African-American antiplatelet stroke prevention study (AAASPS) J Natl Med Assoc. 1998 Mar;90(3):141–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duggan M. Pew Research Center. [2016-10-25]. The demograophics of social media users http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/08/19/the-demographics-of-social-media-users/

- 57.Lord S, Brevard J, Budman S. Connecting to young adults: an online social network survey of beliefs and attitudes associated with prescription opioid misuse among college students. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(1):66–76. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.521371. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/21190407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Young SD, Rice E. Online social networking technologies, HIV knowledge, and sexual risk and testing behaviors among homeless youth. AIDS Behav. 2011 Feb;15(2):253–60. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9810-0. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/20848305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cohort study CASP checklist scores – score out of first 9 questions.