Abstract

In the first article of a series, Devi Sridhar, Janelle Winters, and Eleanor Strong describe how the World Bank has used its influence to catalyse change in global health

The World Bank combines intellectual prestige and financial power, referred to colloquially as “ideas with teeth” or “global health on steroids.” From its first foray into health in the early 1970s to the present, the bank has become one of the largest and most influential health funders worldwide. In 2017 it is particularly important to examine its workings in global health: the re-elected President Jim Yong Kim is the first medical doctor to hold the office and is also an activist and anthropologist who has argued for the right to health. Throughout his tenure, the bank has adopted innovative financing measures for health.

In this five paper series, we provide an overview of the bank’s evolving role in global health, document its turn towards innovative financing in health, and analyse the benefits and risks of such a shift. Our aim is to complement Kamran Abbasi’s 1999 series on the World Bank in international health1 by expanding the themes covered and discussing changes in global health governance since the millennium. We base our analysis on World Bank official documents and reports from its website, the World Bank archives, secondary literature on the World Bank, and conversations with numerous bank staff working in the health, nutrition, and population (HNP) sector. In this first paper, we present the first detailed analysis of the bank’s lending for health and put this into context within its governance structures, and broader role in global health over the past 40 years.

What is the World Bank?

The World Bank was established in 1944 as the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD). Today, IBRD provides loans and technical support to middle income countries and those low income countries it deems creditworthy (at times the loans are contingent on recipients undertaking certain policy reforms called conditionalities). IBRD is only part of the World Bank. Another key arm is the International Development Association (IDA), which was formed in 1960 to provide loans and grants to the poorest countries.

Unlike other UN agencies, such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Bank both raises funds on global capital markets and receives funds from its member states.2 The IBRD is partially funded by capital contributions from its members and is effectively “owned” by its 189 member states. Each country has a weighted number of votes on the bank’s executive board, depending on its capital contributions. Most of IBRD’s funds come from the issuance of World Bank bonds sold on the world’s capital markets, and some income is generated from its interest bearing loans and investment portfolio. In contrast, IDA is funded by replenishments, or donor commitments, made generally every three years. Although the World Bank calls for the replenishments, they are overseen by donors (eg, United States, United Kingdom, Japan), not the World Bank or IDA recipients.

The US is the largest and most influential country in the World Bank, speaking on almost all subjects coming before the executive board.2 The president of the World Bank has always been an American, and the US is the only country to have veto power over decisions of the executive board. When created, IDA’s replenishment model opened up a new channel through which the bank could be directly influenced by wealthier government members. For example, the US has used threats to reduce, or withhold, funding to the IDA in order to demand changes in policy for the entire institution.3 In recent years, trust funds (financial arrangements held by the bank), as the third paper in this series outlines, have become an increasingly important channel for funding health activities. Trust funds are vulnerable to the influence of specific groups of donors because they circumvent core bank allocation processes in order to achieve donor specified objectives.

World Bank in global health

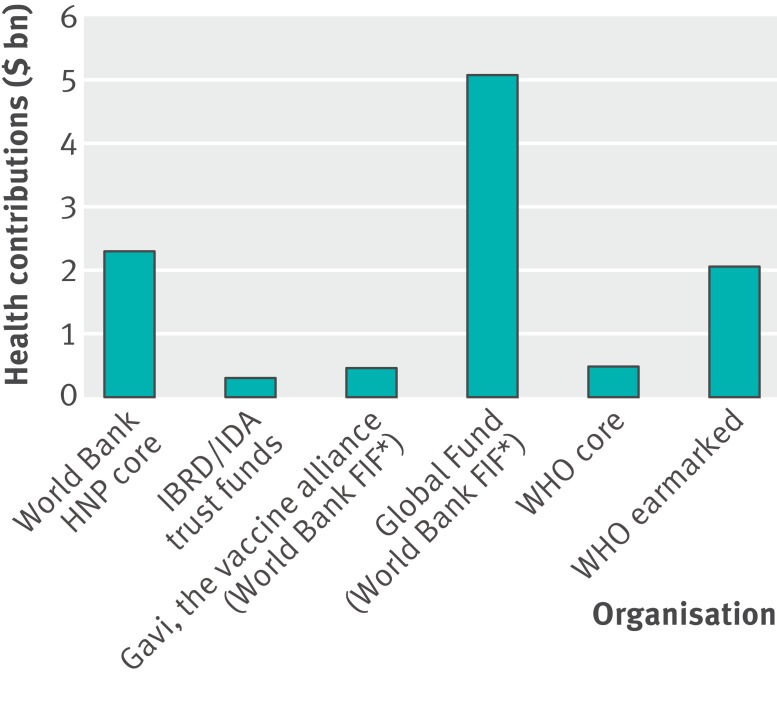

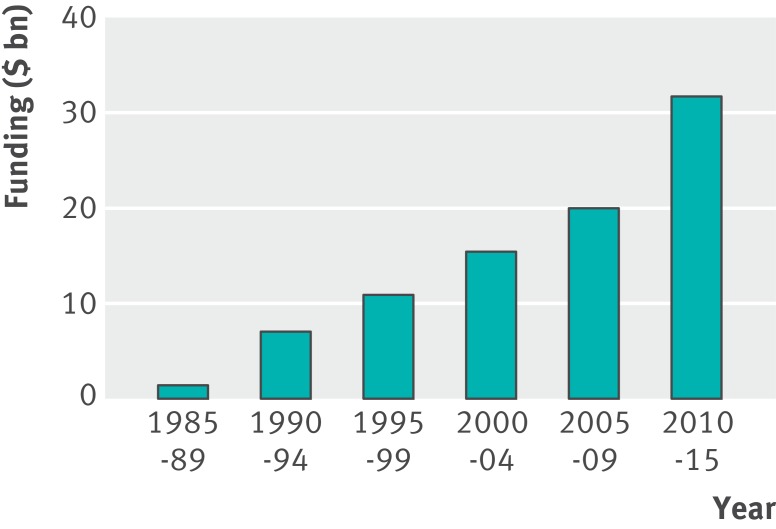

While some might question the importance of the World Bank in global health, it is the largest funder of global health within the UN system and the second largest funder overall (fig 1).4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Major changes in global health governance have taken place since 2000, including the creation of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in 2000, Gavi, the vaccine alliance in 2000, and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria in 2002. Given the narrow focus of all three of these organisations,11 12 the World Bank’s comparative advantage comes to the fore; it engages in a variety of sectors and with ministries of finance to reach health goals, takes on broader non-disease specific objectives such as health sector reform, and supports efforts to strengthen the health workforce. These new organisations do not encroach greatly on the bank’s mandate or substantially weaken its position, in contrast to their effect on WHO’s core work. Indeed, the bank’s absolute spending and general involvement in the health, nutrition, and population (HNP) sector has grown considerably since 1985 (figs 2 and 3).13 14

Fig 1 Funds contributed for health to the World Bank, relative to other major health organisations.4 5 6 7 8 9 10 *Gavi, the vaccine alliance and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria are both financed by customised trust funds—financial intermediary funds (FIFs)—held at the World Bank. The World Bank financial data are collected and released by fiscal year (1 July to 30 June), while the Gavi, Global Fund, and World Health Organization data follow the calendar year. (IBRD=International Bank for Reconstruction and Development; IDA=International Development Association)

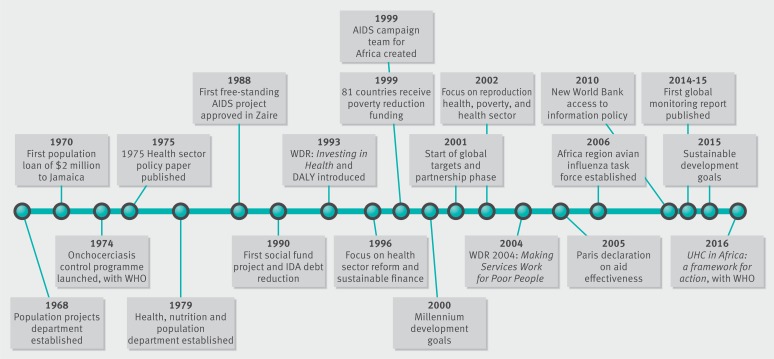

Fig 2 Timeline of health, nutrition, and population (HNP) in the World Bank (adapted from13) (DALY= disability adjusted life year; IDA=International Development Association; UHC=universal health coverage; WDR=World Development Report)

Fig 3 Total health, nutrition, and population (HNP) funding over the past 30 years7

The World Bank is influential in global health for several reasons. Firstly, it has a longstanding relation with ministries of finance, which arguably have more influence over health than do ministries of health. For instance, the bank’s 2013 African Health Forum, on “finance and capacity for results,” brought together ministers of finance and health from 30 African countries to discuss countries’ health needs and promote the link between health interventions and economic growth.15

Secondly, technical support to countries is based on the premise of a loan package, which means that ideas about how to change health sector projects or policies are backed by the necessary resources for implementation. For project lending the bank identifies, designs, and disburses funds for a project with specific objectives. Loans are disbursed over a fixed period according to intermediate targets determined over specified project phases, and the recipient government typically executes the project. The bank also provides policy lending—budgetary support that is contingent on implementation of policy reforms by the recipient government.

Thirdly, the World Bank has created widely accepted key concepts, such as human capital, cost effectiveness, disability adjusted life years (DALYs), and the first estimates of burden of disease in 1993.16 17 18 Fourthly, it cooperates closely with the major new institutions such as the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria and Gavi, the vaccine alliance, which are trust funds (financial intermediary funds) held by the bank. Finally, the bank has a powerful network of people who move in and out of the bank to positions in ministries of finance and health in-country.

While the bank’s relative role in financing the health sector has decreased over the past two decades, owing to the growth of both development assistance for health overall and domestic resources channelled into health, the five factors detailed above have allowed it to use its lending power to catalyse change.19 A study of HIV/AIDS in Brazil and India, for example, pointed to the World Bank’s initial loans as one of the turning points in the decision of these countries to channel more domestic resources into HIV/AIDS.20

Global health in the World Bank

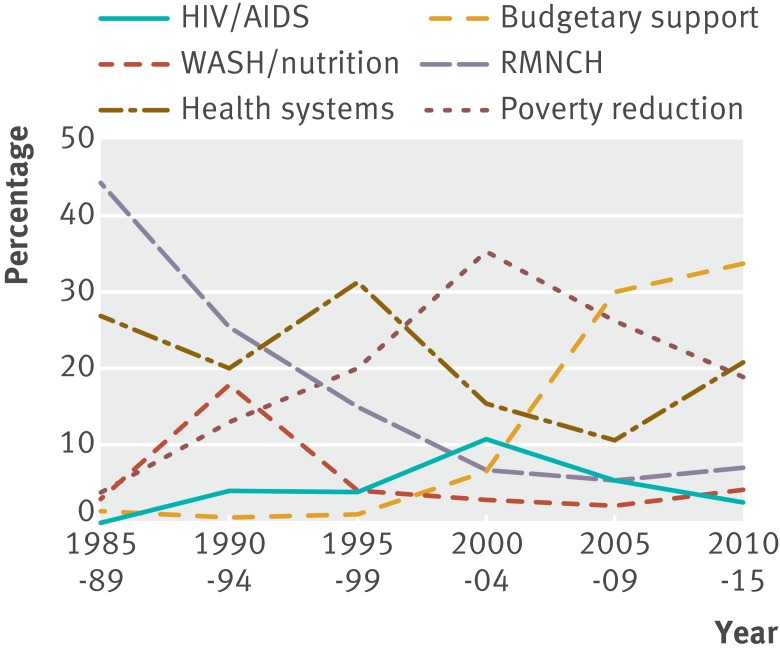

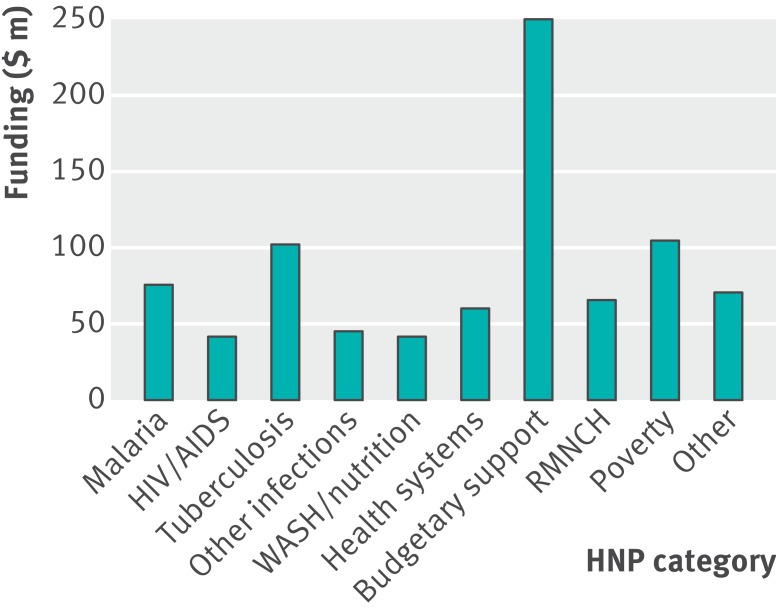

Within the bank, health claims a relatively small share of attention. In 2013-14, loans from core IBRD/IDA health projects in the health and other social services sector stood at less than $3.4bn, out of a total loan pool of more than $40.8bn.21 However, the bank’s increase in overall lending for health projects—from 1% in 1985-89 to 12% in 2010-15—demonstrates a shift in its priority for health lending (table 1). Although absolute financial commitments have increased for health, nutrition, and population overall, the priority given to various health categories has changed (fig 4, fig 5, box 1). For example, reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (RMNCH) funding declined from 44% to 7% from 1985 to 2015, while budgetary support funding increased from 1% to 34%.7 13

Table 1.

Percentage of total World Bank funding allocated to health, nutrition, and population (HNP) projects7

| 1985-89 | 1990-94 | 1995-99 | 2000-04 | 2005-09 | 2010-15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HNP funding ($m) | 1 386 | 7 142 | 10 925 | 15 544 | 20 074 | 32 018 |

| Total World Bank funding ($m) |

92 769 | 111 979 | 120 418 | 100 285 | 162 580 | 261 326 |

| Percentage HNP (%) | 1 | 6 | 9 | 16 | 12 | 12 |

Fig 4 Tracked relative spending for health, nutrition, and population (HNP) categories over the past 30 years7 (RMNCH=reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health; WASH=water, sanitation, and hygiene)

Fig 5 Average funding allocation per project from 1985 to 2015 according to each health, nutrition, and population (HNP) category7 (RMNCH=reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health; WASH= water, sanitation, and hygiene)

Box 1: Definition of health, nutrition, and population (HNP) categories

HIV—Any project involving HIV surveillance, diagnosis, prevention, or treatment

Malaria—Any project involving malaria surveillance, diagnosis, prevention, or treatment

Tuberculosis (TB)—Any project involving TB surveillance, diagnosis, prevention, or treatment

Other infectious disease—Any project involving infectious disease surveillance, diagnosis, or treatment. This includes avian influenza, Zika, Ebola, polio, sexually transmitted infection, and other related disease initiatives

WASH and nutrition—Any HNP project involving water and sanitation or focusing on improving nutrition

Health systems—Any project that aims to improve a country’s overall health system. This includes funding for basic healthcare services, delivering medication, improving primary care in urban and rural areas, and increasing communications within the healthcare system

Budgetary support—Any project involving government support and administration lending, such as policy development initiatives

RMNCH—Any project which involves maternal, child, or reproductive health

Poverty reduction—Any HNP project that is dedicated to enhancing social inclusion and specifically involves poverty reduction credits

Other—Projects within the HNP sector dedicated to infrastructure, road development, education centres, and debt relief loans. Non-communicable diseases are included here as only three projects were in this category

Using our financial analysis of the bank’s HNP portfolio and our review of literature on the World Bank in health, we have identified five major periods in its health funding history. The first period stretches from the bank’s inception until 1968, when Robert McNamara became bank president. Health was neglected during this inaugural epoch as the bank focused on large infrastructure projects rather than investment in social sector development.22 The main focus during these years was on shifting from the bank’s initial emphasis on reconstruction after the second world war towards working in low and middle income countries.

The second period from 1968 to 1980 coincided with the bank’s first loans for disease specific, nutrition, and family planning projects.23 McNamara moved the bank towards a poverty alleviation strategy based in social sector work, initially focusing on family planning and later selecting onchocerciasis (river blindness) as a major priority.

The third period from 1980 to 2000 involved the application of market based solutions and privatisation to healthcare problems, including healthcare delivery; this aligned with broader trends across the bank’s wider portfolio.24 As Abbasi discussed in 1999, the bank advised, and sometimes even forced, poor countries to scale back involvement of the public sector in health through cuts to the health budget and health workers, while also encouraging revenue generation through user fees at the point of care.1

The fourth period from 2000 to 2010 focused on achieving the millennium development goals through cooperation with other stakeholders.25 For instance, the World Bank multicountry AIDS programme in Africa, established in 2000, channelled roughly $1bn to scale up prevention, care, support, and treatment programmes in IDA eligible countries and grew to be the largest funder of HIV/AIDS within the UN system.26

Finally, from 2010 until today, the bank has focused on working with governments to achieve universal health coverage using a range of innovative financing instruments.27 28 With this emphasis on universal health coverage, the bank has reversed course on its previous user fee policy.29 Initiatives like the health results based financing project in Zimbabwe have instead used trust funds to provide grants to local health facilities that remove point-of-care user fees.15 Although traditional core lending projects are still evident, more focus is placed on dealing with specific high profile health concerns through trust funds such as the Global Financing Facility (GFF)30 and the Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility (PEF).31 The World Bank Group more broadly is reinventing itself, from a lender for major development projects to a broker for private sector investment. Kim’s vision for the bank is to use its knowledge and capital to serve as an “honest broker” between the interests of the global market system, emerging country governments, and people in poverty, to ensure that all sides benefit.32

In the rest of this series, we take a closer look at key priorities in global health and the role of the World Bank in shaping and responding to these priorities. In the second article, we examine the universal health coverage and health systems strengthening agenda and critically assess the bank’s history in this area and future directions.33 In the third article, we discuss the growth, benefits, and risks of earmarked aid for global health at the bank and provide a detailed case study of onchocerciasis trust funds that supported the bank’s first flagship health project.34 The fourth article looks at global efforts to achieve maternal, newborn, and child health by examining the Global Financing Facility.30 In the final paper, we scope global efforts towards pandemic preparedness and analyse the bank’s involvement in health outbreaks and emergencies through its proposed Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility.31

The analyses presented in all of the articles are relevant to debates about the collective response to the major health challenges of today and the World Bank’s role within that response. Although this series focuses on particular health concerns and innovative financing mechanisms, future research should explore how the bank’s economics driven approach has affected health policies and outcomes at the country and local level. Many who work in the health sector, whether as clinicians or in the government developing policy, would argue that everyone has the right to health. A clear tension therefore exists between the premise that health is a human right and the bank’s focus on return on investment and productivity. We hope that this series will be a first step in unpacking this tension and understanding the bank’s role in influencing global health policies and defining their success.

Key messages

The World Bank is the largest funder of global health within the UN system and the second largest funder overall

We identify five major periods in the bank’s role in global health in terms of lending, cooperation, and knowledge

Despite the entrance of major new global health organisations the bank has remained relevant through innovative financing mechanisms, close long term relations with country ministries, and developing and applying economic approaches to health

The bank’s increasing reliance on trust funds and innovative financing mechanisms, such as the Global Financing Facility, places health decision making authority in the hands of a small group of donors

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Infographic

Contributors and sources: DS conceptualised and designed the series and drafted the paper. JW collected and analysed the data and revised the paper. ES collected and analysed the data. DS holds a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award on the role of the World Bank in global health and is the coauthor of Governing Global Health: Who Runs the World and Why? (OUP, 2017). JW is a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh and her research focuses on onchocerciasis control programmes, defining success in global health, and the World Bank. ES is a medical student at the University of Edinburgh and her dissertation research focused on analysing lending for health of the World Bank. Data analysed included World Bank financial datasets, archival sources, publications and reports, and staff interviews.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and have no relevant interests to declare. This work was supported by Wellcome Trust [106635/Z/14/Z]. A senior member of the World Bank is on our project’s advisory board.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is one of a series commissioned by The BMJ based on an idea by the University of Edinburgh. The BMJ retained full editorial control over commissioning, external peer review, editing, and publication. Open access fees are funded by the Wellcome Trust.

References

- 1.Abbasi K. The World Bank and world health: changing sides. BMJ 1999;318:865-9. 10.1136/bmj.318.7187.865 pmid:10092271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinton C, Sridhar D. Governing global health: who runs the world and why?Oxford University Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woods N. The United States and the international finance institutions: power and influence within the World Bank and the IMF. In: Weber J, Foot R, Macfarlane SN, Mastanduno M, eds. Hegemony and international organizations.Oxford University Press, 2003. 10.1093/0199261431.003.0005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Financing global health visualizations. 2016. http://vizhub.healthdata.org/fgh/.

- 5.World Bank Group Finances. Paid in contributions to IBRD/IDA/IFC trust funds based on FY of receipt. 2017. https://finances.worldbank.org/Trust-Funds-and-FIFs/Paid-In-Contributions-to-IBRD-IDA-IFC-Trust-Funds-/nh5z-5qch

- 6.World Bank. World Bank lending by sector, fiscal years 2012-16. 2016. http://www.worldbank.org/en/about/annual-report/fiscalyeardata#4

- 7.World Bank. New IBRD/IDA HNP sector commitments by FY and region. 2017. http://datatopics.worldbank.org/health/lending

- 8.GAVI Alliance. Annual financial report 2013. 2014. http://www.gavi.org/library/gavi-documents/finance/financial-reports/2013/gavi-alliance-annual-financial-report/

- 9.Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Annual financial report 2013. 2014. https://www.theglobalfund.org/media/1339/corporate_2013annualfinancial_report_en.pdf

- 10.World Health Organization. Financial report and audited financial statements for the year ended 31 December 2014. 2015.http://www.who.int/about/resources_planning/A68_38-en.pdf

- 11.Storeng KT. The GAVI Alliance and the “Gates approach” to health system strengthening. Glob Public Health 2014;9:865-79. 10.1080/17441692.2014.940362 pmid:25156323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sridhar D, Tamashiro T. Vertical funds in the health sector: lessons for education from the Global Fund and GAVI. Paper commissioned for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report; 2010. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0018/001865/186565e.pdf.

- 13.World Bank. Projects & operations. 2016.http://projects.worldbank.org/search?lang=en&searchTerm=&mjthemecode_exact=8

- 14.Fair M. From population lending to HNP results: the evolution of the World Bank’s strategies in health, nutrition and population. 1st ed. 2008. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/6406/432090NWP0From1Box0327352B01PUBLIC1.pdf?sequence=1

- 15.World Bank Group. 2013 trust fund annual report. 2013. https://siteresources.worldbank.org/CFPEXT/Resources/299947-1274110249410/CFP_TFAR_AR13_High.pdf

- 16. World Bank. World development report 1993: investing in health.Oxford University Press, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farmer P, Kim JY, Kleinman A, Basilico M. Reimagining global health: an introduction.University of California Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruger JP. The changing role of the World Bank in global health. Am J Public Health 2005;95:60-70. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042002 pmid:15623860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sridhar D, Batniji R. Misfinancing global health: a case for transparency in disbursements and decision making. Lancet 2008;372:1185-91. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61485-3 pmid:18926279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sridhar D, Gómez EJ. Health financing in Brazil, Russia and India: what role does the international community play?Health Policy Plan 2011;26:12-24. 10.1093/heapol/czq016 pmid:20400535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Bank. The World Bank annual report 2014. 2014https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/20093

- 22.Ayres RL. Banking on the poor: the World Bank and world poverty. 1st ed MIT Press, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crane BB, Finkle JL. Organizational impediments to development assistance: the World Bank’s population program. World Polit 1981;33:516-53 10.2307/2010134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abbasi K. The World Bank on world health: under fire. BMJ 1999;318:1003-6. 10.1136/bmj.318.7189.1003 pmid:10195978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harman S. The World Bank and HIV/AIDS: setting a global agenda. 1st ed Routledge, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Bank. The Africa Multi-Country AIDS Program 2000-2006: results of the World Bank’s response to a development crisis. World Bank, 2007.http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTAFRREGTOPHIVAIDS/Resources/717147-1181768523896/complete.pdf

- 27.Horton R. Offline: the Kim doctrine. Lancet 2014;384:840 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61458-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clift C. WHO, the World Bank and universal health coverage. Chatham House, 2013. https://www.chathamhouse.org/media/comment/view/191697

- 29.World Bank. World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim’s speech at World Health Assembly: poverty, health and the human future. 2013. http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/speech/2013/05/21/world-bank-group-president-jim-yong-kim-speech-at-world-health-assembly

- 30.Fernandes G, Sridhar D. The World Bank and the global financing facility. BMJ 2017;358:j3995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein F, Sridhar D. Health as a “global public good”: Creating a market for pandemic risk. BMJ 2017;358:j3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Bank. Speech by World Bank Group President Jim Yong Kim: rethinking development finance. 2017.http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/speech/2017/04/11/speech-by-world-bank-group-president-jim-yong-kim-rethinking-development-finance

- 33.Tichenor M, Sridhar D. Universal health coverage, health system strengthening, and the World Bank. BMJ 2017;358:j3347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winters J, Sridhar D. Earmarking for Global Health: benefits and perils of the World Bank’s trust fund model. BMJ 2017;358:j3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Infographic