Abstract

Background:

No drug, used as adjuvant to spinal bupivacaine, has yet been identified that specifically inhibits nociception without its associated side effects.

Aim of the Work:

The purpose of this study is to compare the efficacy of dexmedetomidine and fentanyl with spinal bupivacaine in inguinal hernioplasty.

Patients and Methods:

Sixty patients of inguinal hernioplasty were randomly allocated to one of three groups, Group C (n = 20) – the patients received 15 mg hyperbaric bupivacaine + 0.5 ml saline. Group D – (n = 20) the patients received 15 mg hyperbaric bupivacaine + 10 μg dexmedetomidine diluted with 0.5 ml saline. Group F (n = 20) – the patients received 15 mg hyperbaric bupivacaine + 25 μg fentanyl (0.5 ml). Onset, duration of anesthesia, degree of sedation, and side effects were recorded.

Results:

The onset of anesthesia was shorter in Groups D and F as compared with the control Group C, but it was shorter in Group D than in Group F. The duration of sensory and motor block was prolonged in Group D and F as compared with the control Group C, but it was longer in Group D than in Group F. The postoperative analgesic consumption in the first 24 h was lower in Groups D and F than in Group C, and it was lower in Group D than in Group F.

Conclusion:

Onset of anesthesia is more rapid and duration is longer with less need for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing inguinal hernioplasty under spinal anesthesia with dexmedetomidine and fentanyl than those with spinal alone with tendency of dexmedetomidine to produce faster onset, longer duration, and less analgesic need than fentanyl with similar safety profile.

Keywords: Bupivacaine, dexmedetomidine, fentanyl, inguinal hernioplasty, spinal anesthesia

INTRODUCTION

Lumber spinal subarachnoid anesthesia is commonly employed for inguinal hernioplasty because of its rapid onset, low risk of infection as from catheter in situ, less failure rates, and cost-effectiveness, but it has the drawbacks of shorter duration of block and a lack of postoperative analgesia. In recent years, the use of intrathecal adjuvants has gained popularity with the aim of prolonging the duration of block, better success rate, and patient satisfaction. Adequate pain management is essential to facilitate rehabilitation, accelerate functional recovery, and enabling patients to return to their normal activity more quickly. The quality of the spinal anesthesia has been reported to be improved by the addition of opioids (such as morphine, fentanyl, and sufentanil) and other drugs (such as dexmedetomidine, clonidine, neostigmine, ketamine, and midazolam), but no drug to inhibit nociception is without associated adverse effects.[1]

Dexmedetomidine has become one of the frequently used drugs in anesthetic armamentarium, along with routine anesthetic drugs due to its hemodynamic, sedative, anxiolytic, analgesic, neuroprotective, and anesthetic-sparing effects.[2] α1 to α2 ratio of 1:1600 makes it a highly selective α2 agonist compared to clonidine, thus reducing the unwanted side effects involving α1 receptors. High selectivity of dexmedetomidine to α2 receptors (which mediate analgesia and sedation) has been exploited by various authors in regional anesthesia practice.[3]

By virtue of its effect on spinal α2 receptors, dexmedetomidine mediates its analgesic effects. Dexmedetomidine has been found to prolong analgesia when used as an adjuvant to local anesthetics for subarachnoid, epidural, and caudal blocks.[4]

Fentanyl is a centrally acting synthetic opioid that has been widely used. Intrathecal fentanyl is usually combined with local anesthetic agents for perioperative anesthesia and analgesia. Intraoperative supplementation of bupivacaine spinal anesthesia with intrathecal fentanyl resulted in better quality of spinal anesthesia. Fentanyl is a lipophilic drug potentiates spinal anesthesia, and it is associated with a decreased incidence of side effects such as pruritus, nausea, and vomiting.[5]

PATIENTS AND METHODS

After obtaining Institutional Ethical Committee approval of Zagazig Faculty of Medicine and written informed consent, seventy ASA physical status I and II male patients aged 18–50 years, height 160–190 cm, and weight 50–90 kg scheduled for inguinal hernioplasty under spinal anesthesia were included in this prospective randomized, double-blinded study in the period from October 2014 to May 2015 in Zagazig University Hospitals. Six patients did not fulfill inclusion criteria and four declined to participate in the study as shown in the enrollment chart; randomization was performed through closed-envelope method.

Exclusion criteria included: patients with a history of cardiac disease uncontrolled hypertension, patients with allergy to the study drugs, opium addiction, sedative drugs consumption, and contraindications for spinal anesthesia.

Patients received no premedication and upon arrival of patients into the operating room, electrocardiography, pulse oximetry (SpO2), and noninvasive blood pressure (NIBP) were monitored. Following infusion of 500 ml lactated Ringer's solution and with the patient in the sitting position, lumber puncture was performed at the L3–L4 level through a midline approach using a 25-gauge Quincke spinal needle.

Patients were randomly assigned into three groups:

Group C: Received 15 mg hyperbaric bupivacaine and 0.5 ml normal saline as control

Group D: Received 15 mg hyperbaric bupivacaine and 10 μg of dexmedetomidine diluted with normal saline up to 0.5 ml

Group F: Received 15 mg hyperbaric bupivacaine and 25 μg fentanyl (0.5 ml).

After intrathecal injection, patients were positioned in the supine position and oxygen 2 L/min was given through a face mask. The anesthesiologist performing the block recorded the intraoperative data and a nurse followed the patients postoperatively until discharged from the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). Both were blind to the group to which the patient was allocated. Sensory block was assessed bilaterally using analgesia to pinprick with a short hypodermic needle in the midclavicular line. Motor block was assessed using the modified Bromage scale (Bromage 0: The patient is able to move the hip, knee, and ankle; Bromage1: The patient is unable to move the hip but is able to move the knee and ankle; Bromage 2: The patient is unable to move the hip and knee but able to move the ankle; and Bromage 3: The patient is unable to move the hip, knee, and ankle). The time to reach T10 dermatome sensory block and Bromage 3 motor block was recorded before the surgery. The regression time for sensory and motor block was recorded in a PACU. All durations were calculated considering the time of spinal injection as time zero. Patients were discharged from the PACU after sensory regression to S1 dermatome and Bromage 0.

The three groups were monitored perioperatively for heart rate NIBP and SpO2. Hypotension was defined as systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg or >30% decrease in baseline values. Tachycardia was defined as heart rate >100/min and bradycardia was defined as heart rate <60/min. Intraoperative nausea, vomiting, pruritus, additive analgesia, sedation using Ramsay Sedation Scale, or any other side effects were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Data were checked, entered, and analyzed using SPSS version 11 (SPSS Inc., IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). Data were expressed as a mean ± standard deviation for parametric results. Qualitative data were expressed as a number. ANOVA, paired t-test, Chi-square, or Kruskal–Wallis test were used. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Sample size was calculated using Epi-Info (Epi Info™, GA, USA) program. At 80% power and 95% confidence interval, the estimated sample was twenty patients in each group.

RESULTS

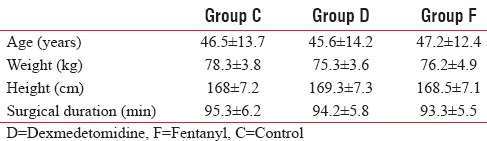

The demographic data did not differ among three study groups [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data values are the mean±standard deviation

These groups were similar in the maximal dermatome height achieved, systolic, diastolic arterial blood pressures, heart rates, and oxygen saturations remained stable, and there was no significant difference among the groups.

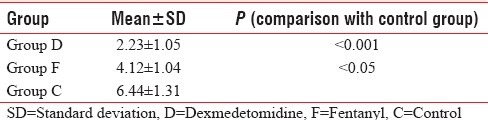

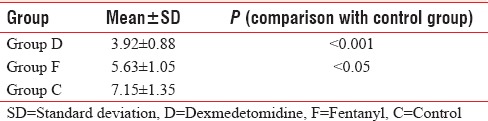

The onset time of sensory block up to T10 dermatome and motor block to Bromage 3 scale was rapid in Group D (2.23 ± 1.05 and 3.92 ± 0.88) and Group F (4.12 ± 1.04 and 4.83 ± 1.05) in comparison with control Group C (6.44 ± 1.31 and 7.15 ± 1.35) [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 2.

Onset times in minutes of sensory blocks for sample groups

Table 3.

Onset times in minutes of motor blocks for sample groups

The onset time of sensory and motor block was rapid in Group D in comparison with Group F.

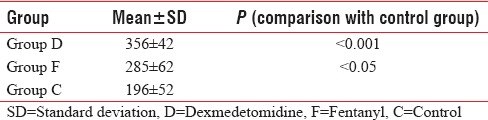

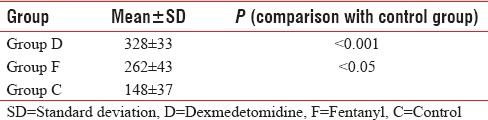

The regression time of block, both sensory up to S1 dermatome and motor to Bromage 0 scale, was prolonged in Group D (356 ± 42 and 328 ± 33) and Group F (285 ± 62 and 262 ± 43) when compared with the control Group C (196 ± 52 and 148 ± 37). However, the duration was longest in Group D among the three groups.

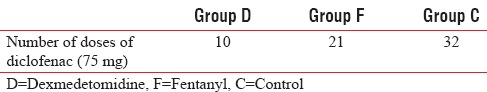

The postoperative analgesic consumption in the first 24 h was significantly lower in Groups D and F than in Group C, and it was significantly lower in Group D than in Group F (P < 0.05).

Three patients from Group D, two from Group F, and two from Group C developed hypotension and received ephedrine, and total intravenous ephedrine dose was not statistically different among the groups [Tables 4–6].

Table 4.

Regression times in minutes of sensory blocks to S1 segment for sample groups

Table 6.

Total doses diclofenac in the first 24 h

Table 5.

Regression times in minutes of motor blocks to Bromage 0 for sample groups

Nausea and vomiting occurred in two patients in Group D and two patients in Group F within 30 min postoperatively compared to no patient in Group C.

The level of sedation score was in the range 0–1 in all three groups with no significant difference.

There were no significant differences in the mean values of heart rate and mean arterial pressures in the 1st h after performing the spinal anesthesia and the 1st h in the PACU between the three group patients.

Twenty-four hours and two weeks postoperatively, follow-up the patients did not show any neurological deficit related to spinal anesthesia such as back pain, leg pain, headache, or any neurological impairment.

DISCUSSION

Dexmedetomidine is the drug which has higher affinity to α2 adrenoreceptors (ten times more than clonidine)[6] which causes it to be a more effective sedative and analgesic agent than clonidine without cardiovascular side effects from α1 receptor activation.[7]

The intrathecal dexmedetomidine prolongs the sensory block when combined with spinal bupivacaine and produces its analgesic effect by inhibiting the release of transmitters of C fibers and by hyperpolarization of postsynaptic dorsal horn neurons.[8]

Motor block prolongation by α2 adrenoreceptor agonists might be caused by impairment of the release of excitatory amino acids from spinal interneuron.[9]

This study shows that the onset time to reach peak sensory and motor level was significantly shorter and significant prolongation of the duration of spinal sensory and motor blockade by intrathecal administration of dexmedetomidine as an adjunct to hyperbaric bupivacaine for patients undergoing inguinal hernioplasty.

The result of Al-Mustafa et al.[10] used intrathecal dexmedetomidine 5 μg added to spinal bupivacaine for urological procedures and found that the onset of sensory block to reach T10 dermatome was shorter.

Al-Ghanem et al.[11] used intrathecal dexmedetomidine 10 μg added to spinal bupivacaine for gynecological procedures and found that the onset of sensory block to reach T10 dermatome was shorter.

Shukla et al.[1] used intrathecal dexmedetomidine (10 μg) as adjuvant to spinal bupivacaine for lower abdominal and lower limb surgery, and it produces earlier onset and prolonged duration of sensory and motor block without associated significant hemodynamic alterations and provides excellent quality of postoperative analgesia.

Hala et al.[12] reported that intrathecal 10 μg dexmedetomidine provided prolonged sensory and motor block of spinal anesthesia in addition to prolonged postoperative analgesia.

Sunil et al.[13] found that patients received intrathecally 15 mg hyperbaric bupivacaine plus 10 μg dexmedetomidine showed prolonged sensory and motor block.

Gupta et al.[14] found that patients were receiving intrathecally 5 μg dexmedetomidine, they showed prolonged motor and sensory block and reduced demand for postoperative analgesics in 24 h compared to control group. We had a similar result in our study.

On the other hand, in the Group F, it was found that the onset times of sensory and motor blockade were shorter than Group C but longer than Group D and durations of both sensory and motor blockade were longer than Group C but shorter than Group D.

Fentanyl combines to the opiate receptors present in the brain and spinal cord where it inhibits the release of nociceptive transmitter substance P.[15] The combination of local anesthetics and fentanyl improves quality and prolongs the duration of regional anesthesia.[16]

Jain et al.[17] stated that fentanyl has high lipid solubility that enables rapid penetration of neural tissue with subsequent rapid onset of action. Siddik-Sayyid et al.[18] showed that the duration of spinal analgesia was significantly increased by the addition of fentanyl, and there was a significant dose-dependent effect of fentanyl of increasing the duration of analgesia. Cowan et al.[19] found that postoperative analgesic consumption was significantly lower in intrathecal fentanyl group compared with bupivacaine control group, this agrees with the result of our study.

CONCLUSION

Intrathecal 10 μg dexmedetomidine as adjuvant to spinal bupivacaine produces earlier onset and prolonged duration of sensory and motor spinal block and provides excellent quality of postoperative analgesia better than intrathecal 25 μg fentanyl without associated significant hemodynamic alterations.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shukla D, Verma A, Agarwal A, Pandey HD, Tyagi C. Comparative study of intrathecal dexmedetomidine with intrathecal magnesium sulfate used as adjuvants to bupivacaine. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2011;27:495–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.86594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panzer O, Moitra V, Sladen RN. Pharmacology of sedative-analgesic agents: Dexmedetomidine, remifentanil, ketamine, volatile anesthetics, and the role of peripheral mu antagonists. Crit Care Clin. 2009;25:451–69. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2009.04.004. vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bekker A, Sturaitis M, Bloom M, Moric M, Golfinos J, Parker E, et al. The effect of dexmedetomidine on preoperative hemodynamics in patients undergoing craniotomy. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:1340–7. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e3181804298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sudheesh K, Harsoor S. Dexmedetomidine in anaesthesia practice: A wonder drug? Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:323–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.84824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu SS, McDonald SB. Current issues in spinal anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2001;94:888–906. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200105000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coursin DB, Coursin DB, Maccioli GA. Dexmedetomidine. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7:221–6. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200108000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Civantos Calzada B, Aleixandre de Artiñano A. Alpha-adrenoceptor subtypes. Pharmacol Res. 2001;44:195–208. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2001.0857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith MS, Schambra UB, Wilson KH, Page SO, Hulette C, Light AR, et al. Alpha 2-adrenergic receptors in human spinal cord: Specific localized expression of mRNA encoding alpha 2-adrenergic receptor subtypes at four distinct levels. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;34:109–17. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00148-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palmeri A, Wiesendanger M. Concomitant depression of locus coeruleus neurons and of flexor reflexes by an alpha 2-adrenergic agonist in rats: A possible mechanism for an alpha 2-mediated muscle relaxation. Neuroscience. 1990;34:177–87. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90311-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Mustafa MM, Abu-Halaweh SA, Aloweidi AS, Murshidi MM, Ammari BA, Awwad ZM, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine added to spinal bupivacaine for urological procedures. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:365–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Ghanem SM, Massad IM, Al Mustafa MM, Al-Zaben KR, Qudaisat IY, Qatawneh AM, et al. Effect of adding dexmedetomidine versus fentanyl to intrathecal bupivacaine on spinal block characteristics in gynecological procedures: A double blind controlled study. Am J Appl Sci. 2009;6:882–7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hala EA, Eid MD, Mohamed A, Hend Y. Dose-related prolongation of hyperbaric bupivacaine spinal anesthesia by dexmedetomidine. Ain Shams J Anesthesiol. 2011;4:83–95. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sunil BY, Sahana KS, Jajee PR. Comparison of dexmedetomidine, fentanyl and magnesium sulfate as adjuvant with hyperbaric bupivacaine for spinal anesthesia: A double blind controlled study. Int J Recent Trends Sci Technol. 2013;9:14–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta M, Shailaja S, Hegde KS. Comparison of intrathecal dexmedetomidine with buprenorphine as adjuvant to bupivacaine in spinal asnaesthesia. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:114–7. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/7883.4023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanjhan R. Opioids and pain. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1995;22:397–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1995.tb02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stein C. Peripheral mechanisms of opioid analgesia. Anesth Analg. 1993;76:182–91. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199301000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jain K, Grover VK, Mahajan R, Batra YK. Effect of varying doses of fentanyl with low dose spinal bupivacaine for caesarean delivery in patients with pregnancy-induced hypertension. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2004;13:215–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siddik-Sayyid SM, Aouad MT, Jalbout MI, Zalaket MI, Berzina CE, Baraka AS. Intrathecal versus intravenous fentanyl for supplementation of subarachnoid block during cesarean delivery. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:209–13. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200207000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cowan CM, Kendall JB, Barclay PM, Wilkes RG. Comparison of intrathecal fentanyl and diamorphine in addition to bupivacaine for caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2002;89:452–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]