Abstract

Background and Objectives:

Supraglottic airway devices (SADs) have revolutionized the pediatric anesthetic practice and got a key role in difficult airway (DA) management. Several modifications of SADs design had come up to improve their safety.

Aim:

The aim of this survey was to determine the current usage of SADs in pediatric anesthetic practice, their availability, and to know any difficulties noted in practice.

Methods:

It was a questionnaire survey among the anesthesiologists who attended the National Pediatric Anesthesia Conference-2016. The questionnaire assessed the current practice preferences of SADs in routine pediatric cases and DA management, availability of various devices, and any difficulties noted in their usage.

Results:

First-generation SADs were widely available (97%), and 64% of respondents preferred to use it for pediatric short cases. 64% felt the use of SADs free their hands from holding the facemask and 58% found better airway maintenance with it. Intraoperative displacement (55%) was the common problem reported and only 11% felt aspiration as a problem. Most of the respondents (73%) accepted its use as rescue device in airway emergency, and 84% felt the need of further randomized controlled studies on safety of SADs in children. The majority were not confident to use SADs in neonates.

Interpretation and Conclusions:

The key role of SADs in DA management was well accepted, and aspiration was not a major problem with the use of SADs. Although many newer versions of SADs are available, classic laryngeal mask remains the preferred SAD for the current practitioner. Further, RCTs to ensure the safety of SADs in children are warranted.

Keywords: Difficult airway, laryngeal mask airway, pediatric, supraglottic airways

INTRODUCTION

Supraglottic airway devices (SADs) have revolutionized the pediatric anesthetic practice and got a key role in difficult airway (DA) management.[1,2] Since the introduction of the classic laryngeal mask airway (LMAc) by Archie Brain in 1988, several modifications of SADs have come up to improve their safety. The newer versions are preferred for airway management in both adults and children now.[3,4,5] There is a paucity of data in literature to confirm the safety of one SAD over other in pediatric practice. Some of the misconceptions about the use of SADs in children are easy displacement, unsuitability for long procedures, and controlled ventilation or they are unsafe to use in newborns or infants <5 kg body weight.[6]

In this survey, we aimed to assess the current use of SADs in routine pediatric anesthetic practice and DA management, their availability and to know any difficulties noted in their usage.

METHODS

It was a questionnaire survey among the practicing anesthesiologists who attended the national pediatric anesthesia conference in 2016. The approval from the Institutional Research Committee was taken. The questionnaire included 14 questions [Appendix 1] to assess the demographic profile, availability of various SADs, current usage preferences of SADs in routine pediatric anesthetic practice, and to know any device has been found to be unsafe or ineffective in usage. The role of SADs in DA management and routine premedication practices in children were also specifically probed. Participation was voluntary, and anonymity was maintained. Survey response was collected, tabulated, and analyzed using Microsoft Excel. Results are expressed as proportion and percentage.

RESULTS

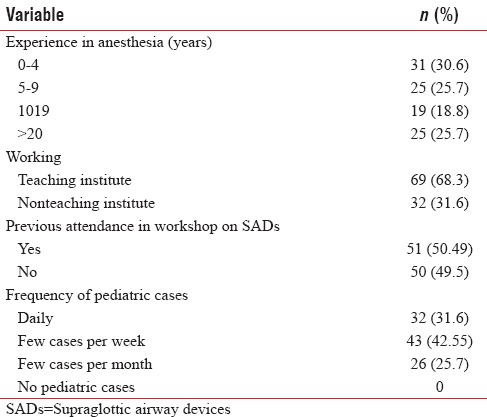

From this survey on the current practice of SADs in pediatric anesthesia, 149 completed responses (59.6%) were collected. Only the responses from the practicing anesthesiologists (n = 101) were considered for further analysis. The demographic details are summarized in Table 1. Practitioners from teaching institutes (68.3%) were the majority, 43.5% had more than 10 years of experience, and 31.6% of them were anesthetizing children almost daily. Fifty percent of respondents attended some kind of training or workshop on SADs before.

Table 1.

Demographic details of respondents

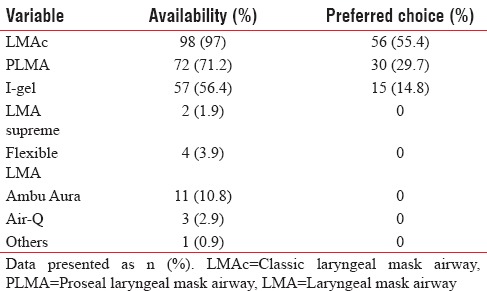

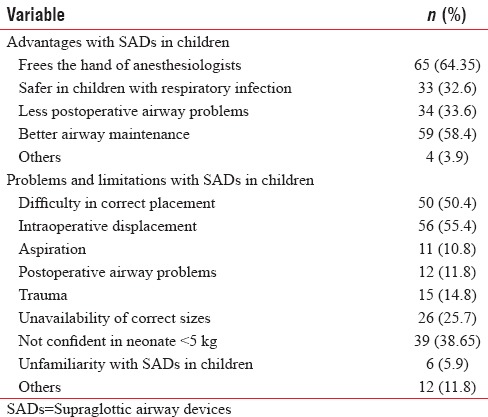

When LMAc was available in almost all of our respondent's workplace (97%), the proseal LMA (PLMA) and I-gel were not so [Table 2]. Availability of other SADs was even lesser (20%). Although the preferred pediatric premedication was oral triclofos or midazolam, 38.6% still practice no premedication for parental separation. The preferred anesthetic technique in a pediatric short case was general anesthesia with SADs along with a regional technique (64.3%). The majority of respondents opted for the first-generation device LMAc (55.4%), followed by the second-generation devices such as PLMA (30%) and I-gel (15%). Seventy-six percent of respondents opted for spontaneous ventilation during maintenance with SADs. Sixty-four percent felt the use of SADs make the anesthesiologist's hands-free from holding the facemask and 58% found better airway maintenance with it. Other advantages reported with the use of SADs were better safety in children with the upper respiratory infection and less postoperative airway problems. Advantages and problems faced by our respondents with SADs usage in children are illustrated in Table 3.

Table 2.

Availability of devices and preferred choice in pediatrics

Table 3.

Advantages and problems faced with supraglottic airway devices in children

Intraoperative displacement (55%) and difficulty in correct placement (50%) were the common problems encountered with SADs usage whereas aspiration (11%), trauma (15%), or postoperative airway problems (12%) were not reported much. Thirty-eight percent of our anesthesiologists were not confident to use a SAD in neonate or babies <5 kg body weight. The unavailability of correct sizes of SADs (25.7%) was also reported as a limiting factor in SADs usage in children.

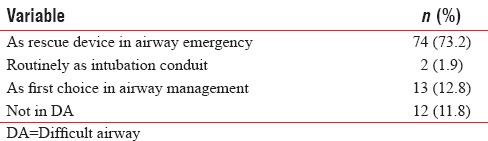

Seventy-three percent of our respondents preferred to use SAD as a rescue device in DA emergency such as “cannot intubate cannot ventilate” scenarios. Only 2% of respondents selected SADs as intubation conduit for fiberoptic bronchoscopy (FOB). SAD as the first choice in DA management was opted by 12.8% only [Table 4]. Most of our respondents (84%) felt the need of further randomized controlled studies/trails (RCTs) on safety of SADs in children.

Table 4.

Use of supraglottic airway devices in pediatric difficult airway

DISCUSSIONS

Our survey throws light into the current usage of SADs in pediatric anesthetic practice in India. There is paucity of published reports on SADs usage in children from India. SADs have come to replace the facemask or tracheal tubes for short procedures, and it is ideal to combine a regional technique along with it.

The first-generation SADs were widely available to our anesthesiologists whereas the second-generation devices, especially I-gel and other newer devices were not freely available. The reason behind this could be the high-cost factor as I-gel is a single use device or the late entry of pediatric sizes of I-gel into our market. There are reports of reuse of I-gel in adults which carries the risk of transmission of infectious materials, especially prions.[7,8] Prion proteins are found to be resistant to autoclaving and cleaning methods.[9,10,11] Ambu Aura was the one newer device available though only a few were familiar with it among the respondents. The studies have demonstrated overall good performance and high success rate with its use in children.[12,13]

In pediatric short cases, where SADs were commonly used, the LMAc was the preferred device among respondents rather than second-generation devices. This could be due to high user familiarity or easy availability. The high success rate at the first placement and fewer incidences of serious complications in children also favored LMAc.[14] Second-generation device like I-gel was less frequently used may be due to lesser availability of it. However, I-gel has high evidence base for better stability even in lateral decubitus position while performing caudal epidural placement.[15] A recent survey from the UK also reported slow acceptance of newer SADs in pediatric anesthetic practice.[16] Personal choice, availability, and institutional protocols may have influence over the selection of device rather than literature evidence. Most of our anesthesiologist felt better airway maintenance with SADs, and it frees the hand of anesthesiologist from holding the facemask to do other tasks. In children with upper respiratory infections, use of SADs has fewer airway-related complications compared to tracheal tubes.[17] In a meta-analysis, use of laryngeal mask compared to tracheal tubes during pediatric anesthesia has found to decrease the postoperative respiratory complications such as laryngospasm, desaturation, cough, and breath holding.[18]

It is alarming that intraoperative displacement was a common problem encountered to our anesthesiologists whereas aspiration was not so. The fourth national audit project by the Royal College of Anaesthetists has pointed out aspiration as a common complication of SADs.[19] Compared to adults, aspiration with SADs is less frequent and carries less morbidity in children. Even though clinical end-points such as square wave capnography and bilateral chest movements are simple ways to assess the placement of SADs, they will not estimate the cuff pressure. Excessive cuff pressure can result in failure to seal the airway properly, and so routine monitoring of cuff pressure is recommended.[20,21] Suboptimally positioned SADs are associated with higher incidence of airway-related complications such as laryngospasm or dislodgment leading to loss of a clear airway.[22] Suboptimal positioning of SAD is more likely in children with DA. Since malpositioning is frequent with SADs, fiberoptic confirmation of correct placement is advised, especially in surgeries where airway access is limited.[23]

Our anesthesiologists were not confident to use SADs in newborns or in babies with <5 kg body weight. More complications were reported earlier with use of SADs in small infants. Size 1 LMA was reported to have the highest complications.[6] However, laryngeal masks are recommended as an alternative airway device to tracheal tubes or face masks during neonatal resuscitation.[24]

Some of the misconceptions about the use of SADs in children are unsuitability for long procedures with controlled ventilation or unsafe to use in newborns. PLMA was designed for controlled ventilation and better airway protection, and pediatric sizes were available in world market since 2005. Even though PLMA was available to 71% of our respondents, only 32% preferred it as a first option SAD in children. PLMA also has fairly well-established evidence base for effective airway management in children. Comparable ventilator efficacy was reported for PLMA even in laparoscopic surgery in children.[25]

SADs got a significant role in DA management, especially in “cannot intubate cannot ventilate” scenarios. Rather LMA was first used for DA management.[18] Although most of our respondents recognized this key role of SADs as rescue device in airway emergencies, only a minority preferred it as a first choice device in DA. There is established evidence that SADs can act as a conduit for FOB-guided intubation in DA.[26] The newer devices such as Ambu Aura-i and Air-Q are designed as conduit for intubation and are found to be equally effective in children.[13,27] But only a very few respondents opted for SADs as an intubation conduit for FOB. This may be due to lack of adequate training and experience with pediatric FOB-guided intubation. Since FOB-guided intubation remains the gold standard in DA management, further training on this aspect should be encouraged. Simulators and manikin-based training sessions can improve the technical as well as critical decision-making skills and teamwork performance in DA management.

Although many studies have assessed SADs usage in children, good quality evidence confirming their safety in children are limited. This was correctly pointed out by our anesthesiologists as need for further RCTs on safety of SADs in children. Few of the limitations of our survey included low response rate, and our respondents were not exclusive pediatric anesthesiologists. The population we studied was specifically interested in pediatric anesthesia; hence, the results may not be applicable to wider sample.

CONCLUSIONS

To conclude, although many newer versions of SADs have come up, LMAc remains to be the most common SADs in routine pediatric practice to our anesthesiologists. The newer devices were less preferred may be due to lesser availability or lack of enough evidence for safety, especially in newborns. The key role of SADs in DA management was well accepted, and aspiration was not pointed out as a major problem. Further, well-powered RCT are needed to establish the safety of newer SADs in children.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

APPENDIX 1: Questionnaire

Supraglottic airway devices in pediatric anesthesia

Please mark your choice(s). Kindly be as specific as you can. Your opinions will be strictly confidential (Thank you for taking time to complete this survey).

-

Working in:

- Teaching hospital: Government medical college/private medical college

- Nonteaching hospital: Government hospital/private hospitals.

-

Experience in anesthesia

- Resident: 1st year/2nd year/3rd year

- Consultant: 0–4 years/5–9 years/10–19 years/>20 years.

Have you ever attended workshop/training on supraglottic airway devices (SADs)? ____(yes/no).

-

How frequently you practice pediatric anesthesia?

- No pediatric cases

- Few cases per month

- Few cases per week

- Daily.

-

Routine premedication you follow before placing SADs

- No premedication in children

- Oral midazolam

- Oral dexmedetomidine

- Anticholinergics only

- Others (specify): _____

-

What all pediatric SADs available in your hospital?

- Classic laryngeal mask airway (LMAc)

- Pro-seal LMA

- I-gel

- Others (specify): _____

-

Your preferred anesthetic technique in pediatric short cases (e.g., Inguinal hernia)

- General anesthesia (GA) spontaneous with mask + caudal

- GA spontaneous with LMA/I-gel + caudal

- GA with endotracheal tube ± caudal

- Others (specify): _____

-

SADs of your choice in pediatrics

- LMA classic

- LMA Pro-seal

- I-gel

- Others: _____

-

Advantages you found with use of SADs in pediatric short cases

- Frees the hand of anesthetist from holding mask

- Safer in children with upper respiratory infection

- Less postoperative airway problems

- Better airway maintenance than mask

- Others: _____

-

Your preferred method of ventilation with SADs in pediatric short cases

- Spontaneous/controlled.

-

What all problems you encounter with usage of SADs in children

- (a) Difficulty in correct placement (b) Aspiration

- (c) Intraoperative displacement (d) Postoperative airway problems

- (e) Trauma-blood on removal (f) Others: _____

-

Your limiting factor in usage of SADs in pediatric anesthesia

- Unavailability of correct size

- Unfamiliarity with SAD usage in children

- Fear of aspiration

- Not confident to use in neonate/<5 kg baby

- Others: _____

-

Do you use SADs in pediatric difficult airway cases?

- As rescue device in emergency (cannot intubate cannot ventilate)

- Routinely for intubation through it with fiberoptic bronchoscopy

- Not in difficult airway

- As first choice of airway management.

-

Do you feel the need for further randomized controlled studies on safety of SADs in:

- Pediatrics: _____ (yes/no).

*Thank you for completing the survey*

REFERENCES

- 1.Weiss M, Engelhardt T. Proposal for the management of the unexpected difficult pediatric airway. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20:454–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2010.03284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apfelbaum JL, Hagberg CA, Caplan RA, Blitt CD, Connis RT, Nickinovich DG, et al. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: An updated report by the American Society of anesthesiologists task force on management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:251–70. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31827773b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez-Gil M, Brimacombe J, Garcia G. A randomized non-crossover study comparing the ProSeal and classic laryngeal mask airway in anaesthetized children. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95:827–30. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jagannathan N, Sohn LE, Sawardekar A, Chang E, Langen KE, Anderson K. A randomised trial comparing the laryngeal mask airway Supreme™ with the laryngeal mask airway Unique™ in children. Anaesthesia. 2012;67:139–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beringer RM, Kelly F, Cook TM, Nolan J, Hardy R, Simpson T, et al. A cohort evaluation of the paediatric I-gel(™) airway during anaesthesia in 120 children. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:1121–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ramesh S, Jayanthi R. Supraglottic airway devices in children. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:476–82. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.89874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadar SM, Koshy R. Survey of supraglottic airway devices usage in anaesthetic practice in South Indian State. Indian J Anaesth. 2015;59:190–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.153044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goyal R. Small is the new big: An overview of newer supraglottic airways for children. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2015;31:440–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.169048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller DM, Youkhana I, Karunaratne WU, Pearce A. Presence of protein deposits on ’cleaned’ re-usable anaesthetic equipment. Anaesthesia. 2001;56:1069–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.02277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clery G, Brimacombe J, Stone T, Keller C, Curtis S. Routine cleaning and autoclaving does not remove protein deposits from reusable laryngeal mask devices. Anesth Analg. 2003;97:1189–91. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000080154.76349.5B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coetzee GJ. Eliminating protein from reusable laryngeal mask airways. A study comparing routinely cleaned masks with three alternative cleaning methods. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:346–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Theiler LG, Kleine-Brueggeney M, Luepold B, Stucki F, Seiler S, Urwyler N, et al. Performance of the pediatric-sized i-gel compared with the Ambu AuraOnce laryngeal mask in anesthetized and ventilated children. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:102–10. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318219d619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jagannathan N, Sohn LE, Sawardekar A, Gordon J, Shah RD, Mukherji II, et al. A randomized trial comparing the Ambu ® Aura-i™ with the air-Q™ intubating laryngeal airway as conduits for tracheal intubation in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22:1197–204. doi: 10.1111/pan.12024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White MC, Cook TM, Stoddart PA. A critique of elective pediatric supraglottic airway devices. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19(Suppl 1):55–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.02997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bopp C, Carrenard G, Chauvin C, Schwaab C, Diemunsch P. The I-gel in paediatric surgery: Initial series. American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Annual Meeting; New Orleans, USA; October 17-21. 2009:A 147. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bradley AE, White MC, Engelhardt T, Bayley G, Beringer RM. Current UK practice of pediatric supraglottic airway devices – A survey of members of the Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23:1006–9. doi: 10.1111/pan.12230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tait AR, Pandit UA, Voepel-Lewis T, Munro HM, Malviya S. Use of the laryngeal mask airway in children with upper respiratory tract infections: A comparison with endotracheal intubation. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:706–11. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199804000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luce V, Harkouk H, Brasher C, Michelet D, Hilly J, Maesani M, et al. Supraglottic airway devices vs. tracheal intubation in children: A quantitative meta-analysis of respiratory complications. Paediatr Anaesth. 2014;24:1088–98. doi: 10.1111/pan.12495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook TM, Woodall N, Frerk C Fourth National Audit Project. Major complications of airway management in the UK: Results of the Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society. Part 1: Anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:617–31. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ong M, Chambers NA, Hullet B, Erb TO, von Ungern-Sternberg BS. Laryngeal mask airway and tracheal tube cuff pressures in children: Are clinical endpoints valuable for guiding inflation? Anaesthesia. 2008;63:738–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2008.05486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Licina A, Chambers NA, Hullett B, Erb TO, von Ungern-Sternberg BS. Lower cuff pressures improve the seal of pediatric laryngeal mask airways. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;18:952–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramachandran SK, Mathis MR, Tremper KK, Shanks AM, Kheterpal S. Predictors and clinical outcomes from failed laryngeal mask airway Unique™: A study of 15,795 patients. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:1217–26. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318255e6ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asai T. Is it safe to use supraglottic airway in children with difficult airways? Br J Anaesth. 2014;112:620–2. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeu005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perlman JM, Wyllie J, Kattwinkel J, Atkins DL, Chameides L, Goldsmith JP, et al. Neonatal resuscitation: 2010 International consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science with treatment recommendations. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1319–44. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2972B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sinha A, Sharma B, Sood J. ProSeal as an alternative to endotracheal intubation in pediatric laparoscopy. Paediatr Anaesth. 2007;17:327–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2006.02127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naguib ML, Streetman DS, Clifton S, Nasr SZ. Use of laryngeal mask airway in flexible bronchoscopy in infants and children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;39:56–63. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jagannathan N, Roth AG, Sohn LE, Pak TY, Amin S, Suresh S. The new air-Q intubating laryngeal airway for tracheal intubation in children with anticipated difficult airway: A case series. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19:618–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.02990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]