Abstract

Background:

Peripheral neural blockade provides effective analgesia with potentially less side effects than an epidural blockade. The present study was undertaken to compare continuous femoral nerve blockade (CFNB) with continuous epidural analgesia (CEA) for postoperative pain control in knee surgeries.

Materials and Methods:

The patients belonging to the American Society of Anesthesiologists Class I and II scheduled for various knee surgeries under spinal anesthesia were enrolled in this study. They were randomly divided into two equal groups of thirty patients each. The Group I patients received CFNB and in the Group II patients epidural catheter was placed preoperatively. Postoperatively, continuous infusion with 0.0625% bupivacaine and fentanyl 2 μg/ml started at 5 ml/h for 72 h in both the groups. Data on Visual Analog Scale (VAS) pain scores, hemodynamic changes, side effects at 0, 1, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h and requirement of analgesic doses for the first 24 h of the surgery were noted.

Results:

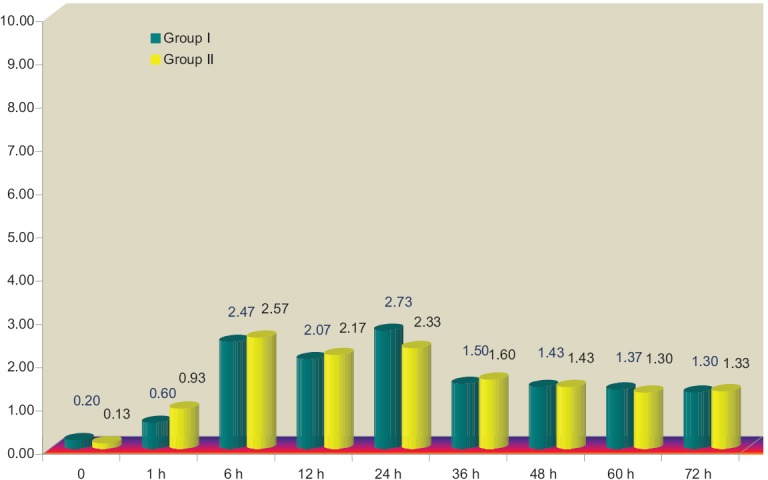

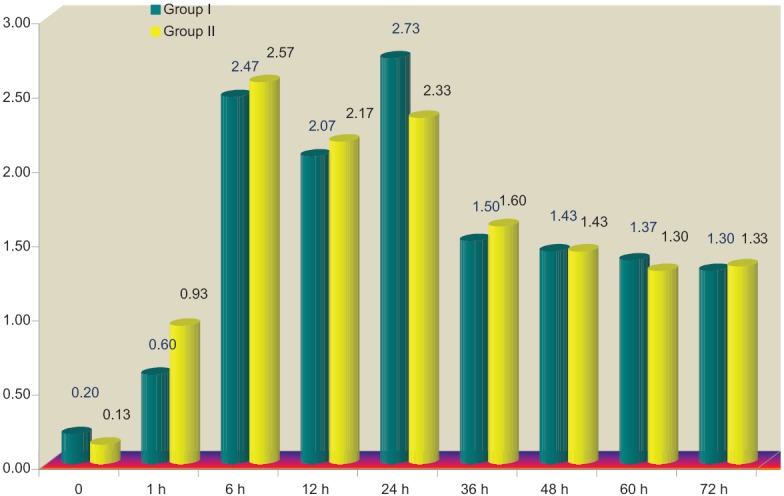

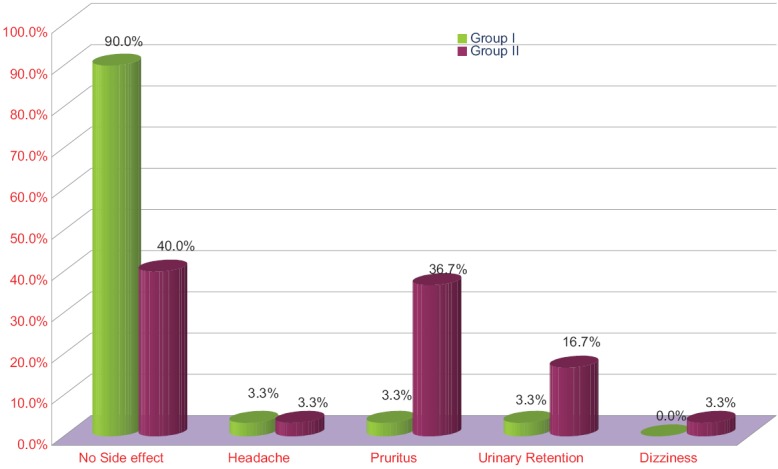

In both the groups, pain was well controlled, mean VAS of pain were 0.2, 0.6, 2.47, 2.07, 2.73, 1.5, 1.43, 1.37, and 1.3 for femoral and 0.13, 0.93, 2.57, 2.17, 2.33, 1.6, 1.43, 1.30, and 1.33 for epidural group during 0, 1, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h which was not statistically significant. Hemodynamics were stable throughout in both the groups. The patients in CEA had more incidences of pruritus and urinary retention.

Conclusion:

CFNB provides postoperative analgesia equivalent to that obtained with a CEA but with fewer side effects.

Keywords: Anesthetic technique, continuous femoral nerve blockade, epidural block, postoperative analgesia

INTRODUCTION

Postoperative pain is still inadequately relieved, despite substantial improvements in the knowledge of the mechanisms and treatment of pain. In addition to the physiological ill effects, the presence of postoperative symptoms including pain significantly contributes to patient's dissatisfaction with their anesthetic and surgical experience. It has been proven beyond doubt that inadequately treated postoperative pain may lead to chronic pain.[1]

Major knee surgery such as total knee joint replacement and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction is associated with moderate to severe postoperative pain. These lower limb procedures are amenable to regional anesthesia techniques which reduce neuroendocrine stress responses, central sensitization of nervous system and muscle spasms which occur in response to painful stimuli.[2] The use of epidural analgesia in the management of postoperative pain following orthopedic surgeries has evolved as a critical component of multimodal approach to achieve the goal of pain relief, early mobilization, and improved compliance with physiotherapy resulting in overall improved outcomes.[3] Patients who receive epidural analgesia may have autonomic disturbances, unintended motor blockade, urinary retention, and pruritis (with opioids as adjuvants) as adverse effects and there is increased risk of neurological complications related to anticoagulant therapy.[3]

An alternative regional anesthesia technique is peripheral nerve blockade of the lower limb. One of the most promising of them is the continuous peripheral nerve blocks (CPNBs) also known as “continuous perineural blocks” which offer tremendous advantage in the perioperative period. CPNB are site-specific and offer superior analgesia and are not associated with the possible side effects of opioid analgesia such as nausea, vomiting, sedation and respiratory depression. There is increasing evidence to indicate that CPNB aid in early mobilization, decrease in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis in the perioperative period, aid better sleep pattern and decrease the incidence of cognitive dysfunction in the perioperative period.[4]

Hence, we aimed to compare continuous femoral blockade with continuous epidural analgesia (CEA) for knee surgeries in terms of efficacy of analgesia, requirement of rescue analgesic agents in the first 24 h of surgery, hemodynamic stability and to determine adverse effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After obtaining approval from the ethical clearance committee, this study was conducted over a period of 18 months. The selection of patients was carried out randomly using a computer-generated number. Written informed consent was obtained from all these patients. Patients aged between 18 and 75 years of both genders belonging to the American Society of Anesthesiologists Class I and II and undergoing elective knee surgery were included in the study. Patients who refused, had infection at the site of injection or coagulation abnormalities, were hypersensitive to the study drugs, had spinal abnormalities were excluded from the study.

Premedication was standardized with tablet pantoprazole 40 mg PO night before surgery and 2 h before surgery, tablet ondansetron 4 mg PO night before surgery and 2 h before surgery and tablet alprazolam 0.5 mg PO night before surgery. Patients were explained the procedure of spinal anesthesia and continuous femoral nerve block or CEA for postoperative pain control at the time of preanesthetic evaluation and instructed about the visual analog scale for pain, i.e., 0 = no pain and 10 = Worst possible pain.

Patients were randomly allocated into two groups:

Group I: Continuous femoral nerve blockade (CFNB) of the operative limb

Group II: CEA.

Patients were monitored continuously using electrocardiography, noninvasive blood pressure and pulse oximetry. CFNB of the operative limb or epidural catheter was placed preoperatively. All the patients in both the groups were administered spinal anesthesia with a standard technique using 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine with an addition of 25 μg of fentanyl.

Postoperatively, continuous local anesthetic (LA) infusion was started at 5 ml/h with an elastomeric pump in both the groups. The infusate contained 0.0625% of bupivacaine and fentanyl 2 μg/ml. Postoperative hemodynamic monitoring continued, data on pain scores using Visual Analog Scale (VAS), and any adverse effects were noted for 72 h. Rescue analgesia in the form of injection tramadol 50 mg intravenously was given if the VAS was >3. The total dose of rescue analgesics administered to the patient in 24 h was noted.

Statistical analysis

The results were averaged (mean ± standard deviation) for continuous data and number and percentage for dichotomous data is presented in table and figure.

Proportions were compared using Chi-square test of significance

Mann–Whitney U-test was applied to find out the significant difference between two independent groups

The student's t-test was used to determine whether there was a statistical difference between two treatments groups in the parameters measured

One-way analysis of variance

One-way analyses of variance were used to test the difference between groups

Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to find out a significant difference between the study groups.

In the entire above test, the P < 0.05 was accepted as indicating statistical significance. Data analysis was carried out using Statistical Package for Social Science package (SPSS version 15.0 IBM Corp, Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

This study was conducted in sixty patients who underwent elective knee surgery.

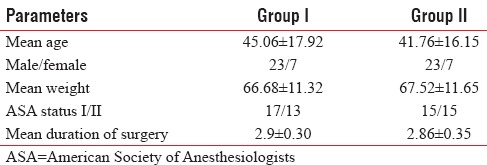

Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation. There were no significant differences in the demographic parameters between the groups [Table 1]

Changes in pulse rate over 72 h were comparable in both groups [Figure 1]

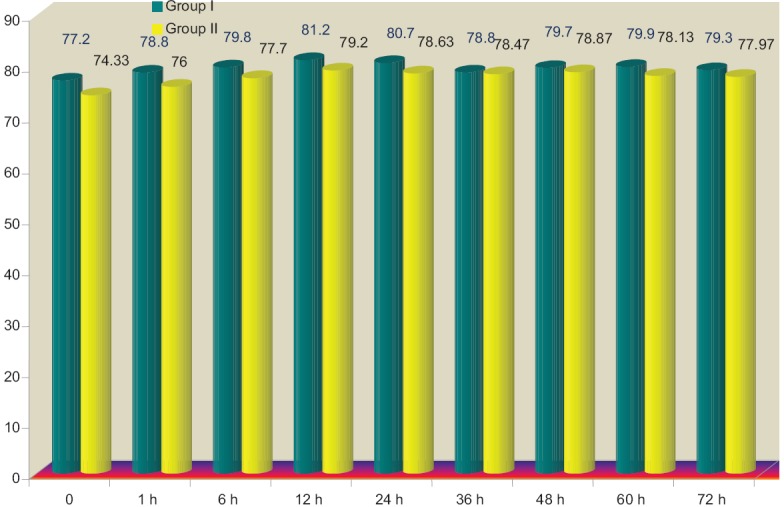

Changes in systolic blood pressure over 72 h were comparable in both groups and were statistically insignificant [Figure 2]

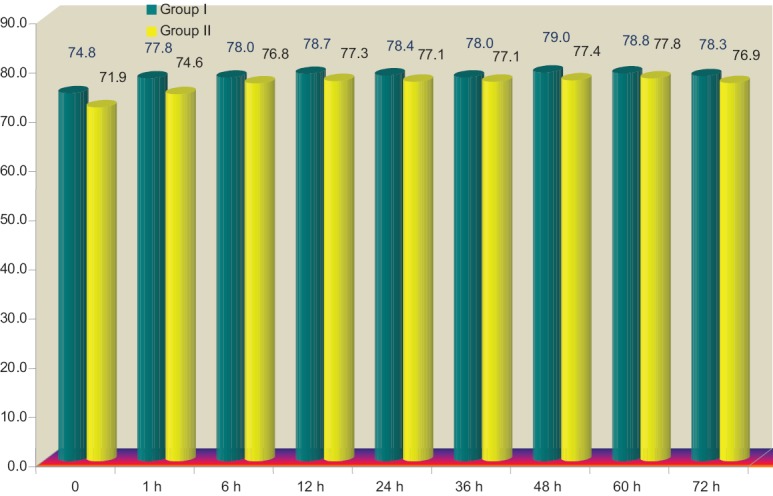

There were no statistically significant changes in DBP over 72 h [Figure 3]

Visual Analogue Scores were comparable over all time intervals [Figures 4 and 5]

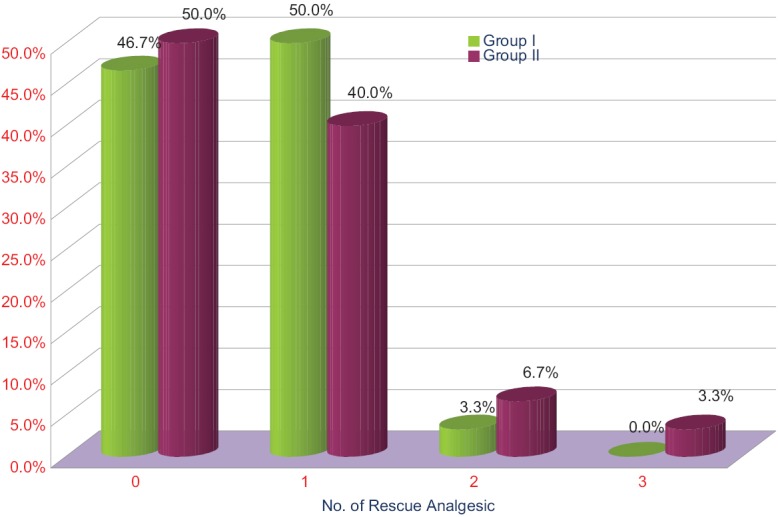

There was no statistically significant difference between the groups with respect to doses of rescue analgesics [Figure 6].

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

Figure 1.

Comparison of mean pulse rate between the study groups at different time points

Figure 2.

Comparison of systolic blood pressure between the study groups at different time points

Figure 3.

Comparison of diastolic blood pressure between the study groups at different time points

Figure 4.

Comparison of Visual Analog Scale scores between the groups over 72 h

Figure 5.

Comparison of Visual Analog Scale scores between the groups over 72 h

Figure 6.

Comparison of doses of rescue analgesics required by both the groups

DISCUSSION

Effective pain control is essential for optimum care and good functional outcome of patients in the postoperative period. However, despite advances in the knowledge of pathophysiology of pain, the pharmacology of analgesics and the development of more effective techniques, patients continue to experience considerable pain after surgery.[5] The emphasis is on total or optimal pain relief allowing normal function without major strain on equipment and surveillance systems or without significant side effects. This could be achieved by adopting combined analgesic regimens. The rationale for this strategy is the achievement of sufficient analgesia due to additive or synergistic effects between different analgesics, with concomitant reduction of side effects. The primary emphasis is made on moderate and severe pain and the use of and need for prolonged, continuous, or intermittent regimens.[5] Opioids reduce the spontaneous rest pain but their ability to control dynamic pain is limited.[5,6]

In the last few years, efforts include the pursuit of nonopioid analgesic adjuncts and refining continuous regional analgesic techniques.[7]

Epidural analgesia continues to be the emphasis of anesthesia-based acute pain services. In general, most recent studies continue to demonstrate the advantages of epidural analgesia if LAs are used in combination with opioids.

Although studies indicate that continuous infusions using lipophilic opioids such as fentanyl administered epidurally or parenterally are equivalent in dosage requirements and quality of analgesia, epidural lipophilic opioids remain popular.

Peripheral nerve blocks (PNBs) provide intense, site-specific analgesia and are associated with a lower incidence of side effects when compared with many other modalities of postoperative analgesia.[8] Continuous catheter techniques provide extended analgesia and improved functional recovery.[9] These advantages can facilitate an early discharge and achieve significant perioperative cost savings. This is of tremendous value in a modern health-care system that stresses cost-effective use of resources and a continued shift toward shorter hospital stay as well as outpatient surgery.[10,11]

Paul et al. conducted a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and found that continuous femoral nerve block was far superior to patient-controlled analgesia for patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty.[12] The innervations of the knee by the sciatic nerve component is minimal. The studies have evaluated the equivalent analgesia with or without sciatic nerve blockade for knee surgeries. The femoral-sciatic block may lead to complications because of motor block of the hamstrings added to the femoral block of the quadriceps muscle might increase the risk of falls and there also a risk of developing heel ulcer.[13]

The continuous femoral nerve infusion of LA has been found to provide similar analgesia but fewer side effects than a single dose of intrathecal morphine,[14] epidural morphine,[15] or a continuous infusion of epidural LA.[16]

Our study showed no significant hemodynamic changes in both the groups during the infusion for 72 h, consistent with the study of Dauri et al.[17]

In our study, the intraoperative anesthesia for surgery was subarachnoid block with bupivacaine and fentanyl. The addition of intrathecal fentanyl prolonged the analgesia without the motor block in both the groups during immediate postoperative period, explaining the extended analgesia in the immediate postoperative period.

The VAS remained within the mild pain range throughout the study period. The efficacy of analgesia in our study is similar to the trend observed by Dauri et al. during 36 h postoperatively.[17] The VAS at rest during continuous passive motion and during physiotherapy were comparable on postoperative days 1 and 2 and 3 between the two groups. In a meta-analysis by Fowler et al., the principal finding is that a PNB technique using femoral nerve blockade provides analgesia, which is comparable with an epidural but with a lower incidence of hypotension.[2]

Patients who complained of pain with corresponding VAS >3 received rescue analgesia (17/19 CFNB/CEA) in the form of injection tramadol 50 mg intravenously. The consumption of analgesic doses among the groups was not significant.

The patients in CEA had more incidences of pruritis 11 versus 1 in the CFNB group, urinary retention 5 versus 1, dizziness in one patient compare to none in CFNB group, and incidence of headache was similar. In the patients with urinary retention, bladder catheterization was done, one patient in either the group had headache which was treated with reassurance and tablet paracetamol and patients with pruritus and dizziness did not require any treatment [Figure 7]. We did not find motor blockade in either group of patients as we used lower concentrations (0.0625%) of bupivacaine and increased the incidence of side effects in the CEI group were probably due to systemic absorption of opioids.

Figure 7.

Comparison of adverse events among the groups

CONCLUSION

In our study, we found that both epidural analgesia and continuous femoral blockade provide effective analgesia and CFNB induces fewer side effects than epidural analgesia. CFNB can be recommended as an effective regional component of a multimodal analgesia strategy after knee surgery. Use of CFNB provides prolonged duration of analgesia and is preferable for those who present challenges regarding catheter placement such as with previous lumbar spine surgery and on anticoagulant therapy.

Limitations

However, there are insufficient data to provide firm recommendations for virtually all aspects of CFNB analgesia. Future work will need to determine which surgical procedures gain benefit from CFNB, what optimal solutions for each application, and optimal means of delivery for each application. The further trial may need to show advantages beyond improved analgesia and decreased side effects to justify their continued use.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Joshi GP, Ogunnaike BO. Consequences of inadequate postoperative pain relief and chronic persistent postoperative pain. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2005;23:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.atc.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fowler SJ, Symons JS, Sabato S, Myles PS. Epidural analgesia compared with peripheral nerve blockade after major knee surgery. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:154–64. doi: 10.1093/bja/aem373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Richman JM, Wu CL. Epidural analgesia for postoperative pain. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2005;23:125–40. doi: 10.1016/j.atc.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balavenkatasubramanian J. Continuous peripheral block: The future of the regional anesthesia? Indian JAnesth. 2008;52:506–16. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karanikolas M, Swarm RA. Current trends in perioperative pain management. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2000;18:575–99. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8537(05)70181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saxena AK, Arava S. Current concepts in neuraxial administration of opiods and non opiods: An overview andfuture prospectives. Indian J Anaesth. 2004;48:113–24. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carpenter RL, Abram SE, Bromage PR, Rauck RL. Consensus statement on acute pain management. Reg Anesth. 1996;21(6 Suppl):152–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danninger T, Opperer M, Memtsoudis SG. Perioperative pain control after total knee arthroplasty: An evidence based review of the role of peripheral nerve blocks. World J Orthop. 2014;5:225–32. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i3.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayek SM, Ritchey RM, Sessler D, Helfand R, Samuel S, Xu M, et al. Continuous femoral nerve analgesia after unilateral total knee arthroplasty: Stimulating versus nonstimulating catheters. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:1565–70. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000244476.38588.c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chelly JE, Greger J, Gebhard R, Coupe K, Clyburn TA, Buckle R, et al. Continuous femoral blocks improve recovery and outcome of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:436–45. doi: 10.1054/arth.2001.23622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Evans H, Steele SM, Nielsen KC, Tucker MS, Klein SM. Peripheral nerve blocks and continuous catheter techniques. Anesthesiol Clin North America. 2005;23:141–62. doi: 10.1016/j.atc.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul JE, Arya A, Hurlburt L, Cheng J, Thabane L, Tidy A, et al. Femoral nerve block improves analgesia outcomes after total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesthesiology. 2010;113:1144–62. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181f4b18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kadic L, Boonstra MC, DE Waal Malefijt MC, Lako SJ, Van Egmond J, Driessen JJ. Continuous femoral nerve block after total knee arthroplasty? Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:914–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.01965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarkkila P, Tuominen M, Huhtala J, Lindgren L. Comparison of intrathecal morphine and continuous femoral 3-in-1 block for pain after major knee surgery under spinal anaesthesia. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 1998;15:6–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2346.1998.00211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schultz P, Anker-Møller E, Dahl JB, Christensen EF, Spangsberg N, Faunø P. Postoperative pain treatment after open knee surgery: Continuous lumbar plexus block with bupivacaine versus epidural morphine. Reg Anesth. 1991;16:34–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capdevila X, Barthelet Y, Biboulet P, Ryckwaert Y, Rubenovitch J, d’Athis F. Effects of perioperative analgesic technique on the surgical outcome and duration of rehabilitation after major knee surgery. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:8–15. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199907000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dauri M, Polzoni M, Fabbi E, Sidiropoulou T, Servetti S, Coniglione F, et al. Comparison of epidural, continuous femoral block and intraarticular analgesia after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2003;47:20–5. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.470104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]