Abstract

Background:

Desirable adjuvants to caudal ropivacaine are the one which prolongs analgesia and free of side effects. We compared nonopioid drugs dexmedetomidine, dexamethasone, and magnesium as adjuvants to ropivacaine caudal analgesia in pediatric patients undergoing infraumbilical surgeries.

Materials and Methods:

This study was done on 128 pediatric patients (3–12-year olds) undergoing infraumbilical surgeries; they were randomly allocated to four groups to receive normal saline, dexmedetomidine 1 μg/kg, dexamethasone 0.1 mg/kg, and magnesium sulfate 50 mg with injection ropivacaine 0.2% in the dose 0.5 ml/kg caudally. Modified Objective Pain Score and Ramsay Sedation Score, duration of analgesia, hemodynamic changes, and side effects were assessed. ANOVA test was used for numerical values as data were expressed in mean and standard deviation. Kruskal–Wallis test was used for postoperative pain and sedation score as data were expressed as median and range.

Results:

The demographic data and hemodynamics were comparable. There was a significant prolongation of duration of analgesia in all study groups, dexmedetomidine (406.2 ± 45.5 min), dexamethasone (450.0 ± 72.6 min), and magnesium (325.0 ± 45.8 min) as compared to ropivacaine (285.9 ± 52.7 min) group. None of the adjuvants resulted in either excess or prolonged sedation. No side effects were encountered.

Conclusion:

The adjuvants dexmedetomidine, dexamethasone, and magnesium added to ropivacaine prolong caudal analgesic duration without any sedation or side effect.

Keywords: Adjuvants, caudal, dexamethasone, dexmedetomidine, magnesium, postoperative analgesia, ropivacaine

INTRODUCTION

Pediatric anesthesia has evolved a long way in making surgical procedures much safer, anesthesia-induced neurotoxicity lesser, and postoperative analgesia much longer. In the pursuit of achieving these goals, regional blocks supplementing anesthesia evolved and they remain one of the most reliable and efficient means. Caudal blocks are time tested for infraumbilical surgeries.[1] Single-shot blocks may not last long and would still depend on the dose, volume, and concentration. An excess of any of this could lead to unintended motor blocks, hemodynamic disturbances, and systemic side effects. To strike a balance between the analgesic efficacy and safety, it has always been a challenge. It may not always be feasible to prolong the duration by placing continuous catheters. Adjuvant to local anesthetics, bridge the gap by prolonging the duration of single shot blocks. However, it is still a dilemma whether additives improve the outcome and outweigh the potential harm or not.

Opioids used as adjuvant carry the disadvantage of occasional delayed respiratory depression, especially when combined with systemic administration. Other adverse effects could be nausea and vomiting, pruritus, urinary retention, and postoperative ileus.[2,3,4] Dexmedetomidine a novel selective α-2 agonist with a favorable pharmacokinetic profile and versatility with slight concern of bradycardia, has shown promise as an adjuvant in neuraxial use as shown by many recent trials.[5,6,7,8,9,10,11] Dexamethasone with its analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antiemetic properties has been safely used perineurally with good outcome in prolonging the analgesia as agreed with a number of studies.[9,12,13,14,15] Magnesium has reemerged as antinociceptive by regulating calcium influx into the cells. It prolongs analgesic duration after caudal block in children.[16,17]

No study comparing these nonopioid adjuvants in terms of analgesia, sedation, hemodynamics, and adverse effects has been done. Hence, we intended to explore the options of using this adjuvant to caudal ropivacaine in patients undergoing infraumbilical surgeries.

Aim of the study

This study analyzes the efficacy of adjuvants dexmedetomidine, dexamethasone, and magnesium as an adjuvant to ropivacaine in caudal analgesia in pediatric infraumbilical surgeries in terms of duration of postoperative analgesia, postoperative sedation, intraoperative hemodynamics, and postoperative side effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of patients before the surgery. One hundred and twenty-eight pediatric patients with physical status American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Classes I and II, aged 3–12 years, scheduled for infraumbilical surgeries, were included in this study from December 2015 to August 2016.

The exclusion criteria were patients with contraindication to caudal anesthesia, cardiovascular diseases, drug allergy, and coagulation disorders, or those whose families did not approve inclusion in the study.

Once the patient is in operating room, the standard monitors including pulse oximetry, electrocardiogram, and noninvasive blood pressure were attached. Standard general anesthesia technique was followed in all patients using injection fentanyl 2 μg/kg and injection thiopentone 5 mg/kg and insertion of I-gel facilitated by injection atracurium 0.5 mg/kg and anesthesia maintained by sevoflurane 1.0–1.2 minimum alveolar concentration by controlled ventilation.

Caudal anesthesia was performed in lateral decubitus position using 22-gauge needle by the loss of resistance technique, and the anesthesiologist-injected drugs blinded for its content by randomly picking one of the four groups.

Group I (control) - 0.5 ml/kg of injection ropivacaine 0.2% + 0.9% normal saline

Group II - 0.5 ml/kg of injection ropivacaine 0.2% + dexmedetomidine 1 μg/kg

Group III - 0.5 ml/kg of injection ropivacaine 0.2% + dexamethasone 0.1 mg/kg

Group IV - 0.5 ml/kg of injection ropivacaine 0.2% + magnesium sulfate 50 mg.

The volume of drug injected would be 0.5 ml/kg.

The surgical procedure started after at least 10 min from caudal block and the block considered failed if the heart rate (HR) or mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) change was 15% from the baseline and that patient excluded from the study and intravenous (IV) fentanyl (1 μg/kg) was given to provide the analgesia.

At the conclusion of the surgery, patients’ I-Gel was removed when adequate spontaneous ventilation was established and then patients were transferred to the recovery room.

The demographic data (age, weight, ASA status, type, and duration of surgery) and the following parameters were recorded: HR and MAP at baseline, after induction, after caudal block, and 5 min after skin incision and immediate postoperatively.

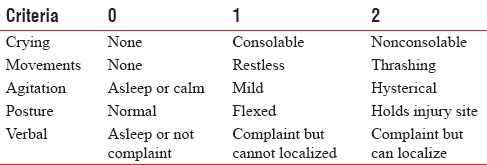

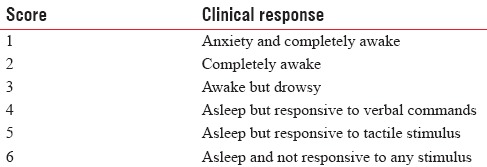

In the postoperative anesthesia care unit (PACU), the Modified Objective Pain Score (MOPS)[18] and Ramsay Sedation Score (RSS)[19] were assessed at 30 min, 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 h as in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Modified Objective Pain Score

Table 2.

Ramsay Sedation Score

If the MOPS >4, the patient will receive supplementary paracetamol IV injection in a dose of 15 mg/kg as rescue analgesia. The time from caudal block to the first time to paracetamol injection was noted and considered as duration of analgesia.

Any adverse effect in PACU was monitored.

Statistical data analysis

Data were obtained from the previous studies that the addition of caudal dexmedetomidine had prolonged duration of analgesia than the caudal local anesthetic alone with power calculation according to data obtained. The number of sample size of thirty patients in each group was adequate with a = 0.05 and a power of 0.8. The sample size increased to 128 patients in this study. Statistical analysis of data was carried out as for all comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The statistical software SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and Statistical Package for Social Sciences 15.0 (SPSS version 15.0 IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) were used for the analysis of the data and Microsoft Word and Excel have been used to generate graphs, tables, etc. ANOVA test was used for numerical values as data were expressed in mean and standard deviation (age, duration of surgery, duration of analgesia, MAP, HR) and Chi-square test was used for categorical values as data were expressed in number of patients or ratio. Kruskal–Wallis test was used for postoperative pain and sedation score as data were expressed as median and range.

RESULTS

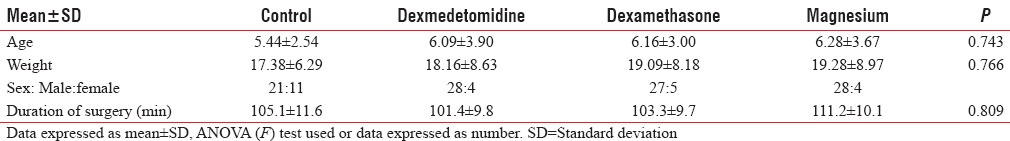

This study was conducted on 128 pediatric patients aged 3–12 years who underwent infraumbilical surgeries. The groups were demographically same in relation to age, weight, and surgical time as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Demographic data

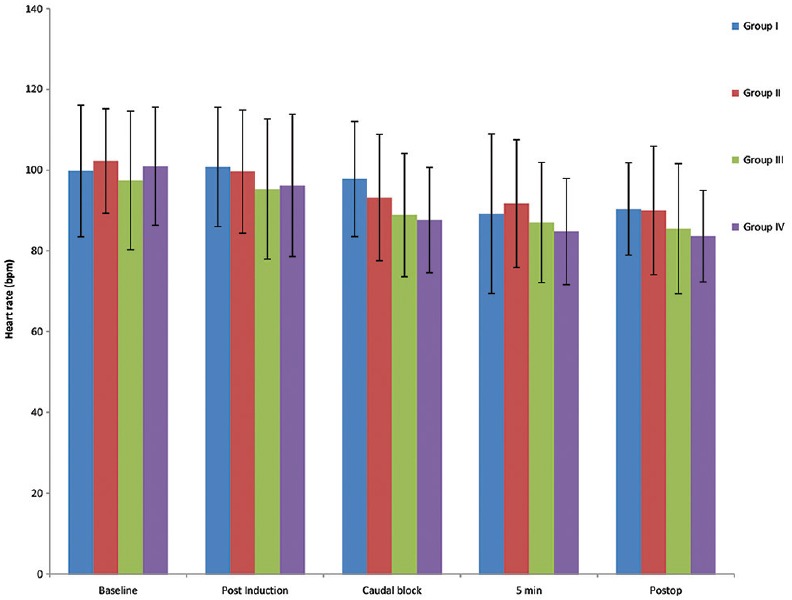

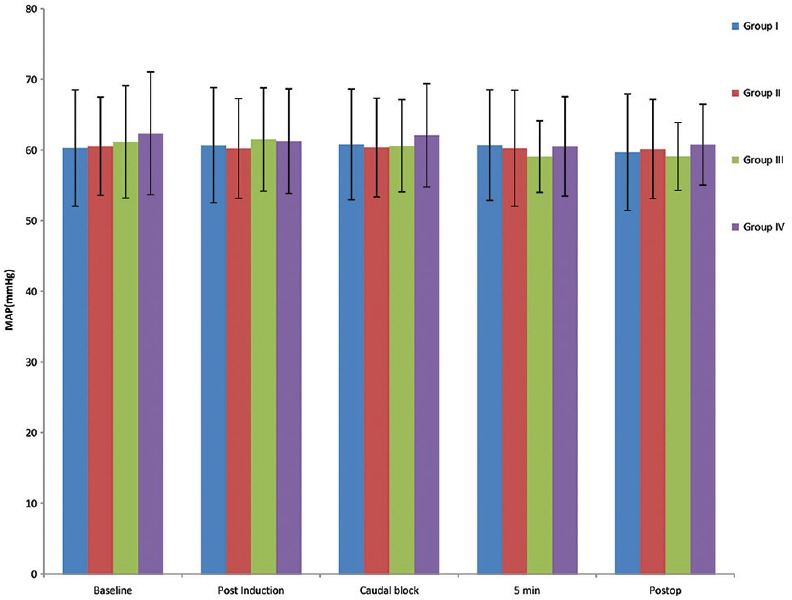

The means of HR changes among the studied groups were comparable at all times monitored as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mean heart rate in all four groups at various timelines.

The means of MAP changes among the studied groups were comparable at all times as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Mean of mean arterial pressure of all four groups at various timelines.

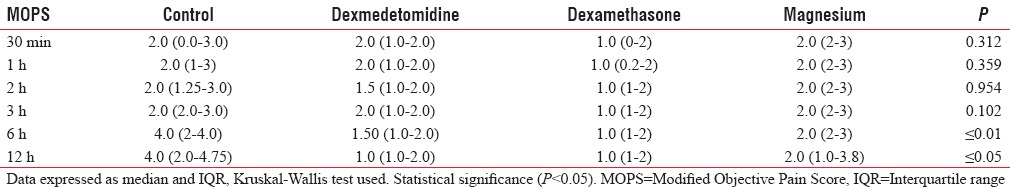

Table 4 shows MOPS presented as median (interquartile range) which was comparable in the first 3 h between the groups. From 6 to 12 h, the pain score was significantly decreased in dexmedetomidine, dexamethasone, and magnesium groups without significant difference in between them compared to ropivacaine group.

Table 4.

Modified Objective Pain Score in four groups

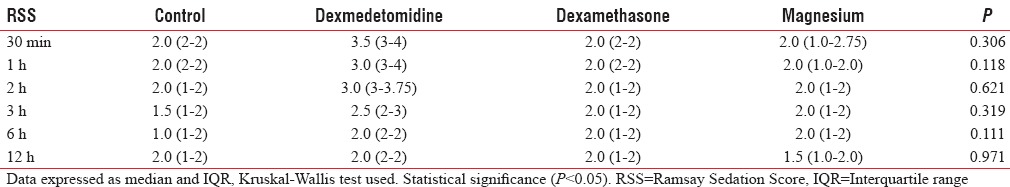

Table 5 shows RSS presented as median (interquartile range) which shows no significant changes between the groups.

Table 5.

Ramsay Sedation Score in four groups

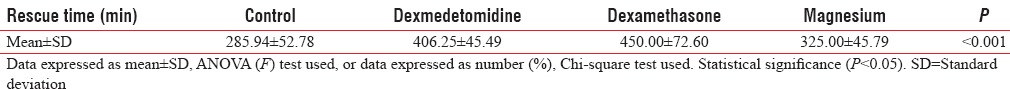

Table 6 shows prolonged duration of analgesia significantly in all the study groups (dexmedetomidine, dexamethasone, and magnesium) compared to the ropivacaine group without significant difference in between them.

Table 6.

Duration of analgesia

No adverse effect was noted in any of the groups.

DISCUSSION

All the adjuvants used in the current study prolonged the duration of caudal analgesia compared to ropivacaine alone. The addition of adjuvants was not associated with increased sedation. Each adjuvant is unique in its mechanism of action and is considered safe and is efficient in prolonging the duration of analgesia.

Evidence showed that neuraxial dexmedetomidine produces antinociception by inhibiting the activation of spinal microglia and astrocyte,[20,21] decreasing noxious stimuli evoked release of nociceptive substances[22] and further interrupting the spinal neuron-glial cross talk and regulating the nociceptive transmission under chronic pain condition.[23] Its sedative and analgesic property provides calm and pain-free postoperative patient with little hemodynamic side effects.

Dexamethasone has direct membrane stabilizing action on nerves and is believed to have a local anesthetic effect[24] and by regulating nuclear factor kappa B inhibits central sensitization after surgery and potentiates analgesia of the caudal block[25,26] without any significant adverse effect.[14,16,17]

Magnesium, a noncompetitive N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist, extends analgesia primarily based on the regulation of calcium influx into the cell when used caudally.[27] It gives superior quality of analgesia and faster return of normal functional activity than local anesthetic alone.

The demographic data were similar among the groups studied.

The postoperative pain score was comparable among the groups till 3 h. There was statistically significant difference in MOPS at 6 and 12 h between study (dexmedetomidine, dexamethasone, and magnesium) and control (ropivacaine) groups (P < 0.01) with no intergroup variation in the study group. The mean duration of analgesia among the Groups I, II, III, and IV was 285.9 ± 52.7 min, 406.2 ± 45.5 min, 450.0 ± 72.6 min, and 325.0 ± 45.8 min, respectively, which was statistically significant (P < 0.001) prolongation in study (dexmedetomidine, dexamethasone, magnesium) group as compared to control (ropivacaine) group.

Dexmedetomidine group had a duration of analgesia of 406.2 ± 45.5 min which is in agreement with Goyal et al. as they randomized 100 children aged 2–10 years undergoing infraumbilical surgeries to either receive dexmedetomidine with bupivacaine or bupivacaine alone caudally. They observed that postoperative analgesic duration was significantly prolonged in dexmedetomidine group with 9.88 ± 0.90 h versus 4.33 ± 0.98 h in bupivacaine alone group.[10] Further supported by Anand et al. who randomized sixty children into two groups receiving ropivacaine with dexmedetomidine (Group RD) and ropivacaine alone (Group R). Pain assessed with face, legs, activity, cry, consolability showed that the duration of postoperative analgesia recorded a median of 5.5 and 14.5 h in Groups R and RD, respectively (P < 0.001).[7] A meta-analysis done by Wu et al. confirmed that neuraxial dexmedetomidine as local anesthetic adjuvant significantly decreased postoperative pain intensity (−1.29 [−1.70–−0.89] P < 0.00001), prolonged analgesic duration (6.93 h [5.23–8.62] P < 0.00001).[5] Saadawy et al. and Xiang et al., who compared local anesthetic (ropivacaine or bupivacaine) with and without dexmedetomidine for caudal analgesia, showed that the duration of analgesia was significantly longer with dexmedetomidine administration (P < 0.001).[6,8] Kamal et al. used dexmedetomidine caudally with ropivacaine in children aged 2–10 years to study hemodynamic variables, end-tidal sevoflurane, and emergence time, postoperative analgesia, requirement of additional analgesic, sedation, and side effects for the first 24 h and concluded that dexmedetomidine group prolonged postoperative analgesia (750 vs. 390 min), without clinically significant side effects, sedation, or hemodynamic disturbances.[11]

Dexamethasone group had pain-free postoperative period of 450.0 ± 72.6 min, Which was similar to study by Choudhary et al where they enrolled 128 patients of 1-5 years who underwent inguinal herniotomy into Group A and Group B randomly to receive either ropivacaine or ropivacaine with dexamethasone for caudal analgesia. Postoperative pain scores measured at 1, 2, 4, and 6 h were lower in Group B as compared to Group A. The mean duration of analgesia in Group A was 248.4 ± 54.1 min and in Group B was 478.046 ± 104.57 min, with P < 0.001 as seen in our study.[12] Sinha et al. showed that duration of analgesia after caudal block in sixty pediatric patients aged about 1–6 years who underwent urogenital surgeries was significantly prolonged in clonidine group (15 h) than dexamethasone group (8 h), but clonidine group had significant postoperative sedation and two patients had bradycardia.[13]

Girgis assessed the effect of adding dexamethasone to bupivacaine on the duration of a caudal block in pediatric patient undergoing inguinal herniotomy or hypospadias surgery and also showed that it significantly prolongs the duration of postoperative caudal analgesia and decreased the intensity of postoperative pain.[14]

El-Feky et al used MOPS to evaluate pain in 120 children of 3-10 years who received fentanyl, dexmeditomedine or dexamethasone as caudal additive to bupivacaine scheduled for lower abdominal surgeries found that both dexamethasone and dexmedetomidine extended the postoperative analgesia significantly with mean duration of 490.4 ± 13.6 min and 498.2 ± 15.4 min similar to our study with almost no side effect.[9]

Magnesium group extended caudal analgesia for 325.0 ± 45.8 min which almost agrees with Yousef et al., who added either dexamethasone or magnesium to ropivacaine to caudal analgesia of children aged 1–6 years undergoing inguinal hernia repair. They found that the duration of analgesia is significantly higher in the magnesium group (8 h [5–11]) and dexamethasone group (12 h [8–16]) than the group receiving ropivacaine alone (4 h [3–5]). Furthermore, there was statistically significant difference between dexamethasone and magnesium as regards to the analgesia duration without an increase in the side effects.[16] Kim et al. used ropivacaine or ropivacaine with magnesium 50 mg in eighty children, 2–6 years of age, undergoing inguinal herniorrhaphy. The Parents’ Postoperative Pain Measure score and analgesic consumption were significantly lower for magnesium group. The time to return of normal functional activity was shorter in magnesium group (P < 0.05), with no difference in the incidence of adverse effects.[17]

RSS monitored in this current study inferred that none of the adjuvants resulted in either excessive or prolonged sedation. In studies where dexmedetomidine was used as an adjuvant, RSS was more which means that children were asleep but easily arousable. Neuraxial dexmedetomidine was associated with beneficial alterations in postoperative sedation scores, produced a better quality of sleep and a prolonged duration of sedation (P < 0.05).[6,7,11]

The hemodynamic parameters such as HR and systolic, diastolic, and mean blood pressure were similar among the groups studied which is similar to Saadawy et al., where no statistical difference between dexmedetomidine and bupivacaine groups.[6] However, a meta-analysis by Wu et al. depicted that there is increased risk of bradycardia (odds ratio of 2.68 [1.18–6.10] P = 0.02) with no increased risk of other adverse events.[5] No similar effects were seen in either dexamethasone or magnesium group.

There were no incidences of hypotension, bradycardia, or respiratory depression in any of the groups.

Limitations

The adjuvants by its varied mechanism of action can exert analgesic action on systemic absorption after caudal block. Many studies used dexmedetomidine, dexamethasone IV as an analgesic but in a dose higher than caudal. Hyperglycemia and adrenal suppression seen with dexamethasone administration were not monitored as previous studies have demonstrated that a single small dose of dexamethasone is not associated with the significant adverse effect.[28] The dosages of the drug used in this study were based on previous other studies.

CONCLUSION

The caudal adjuvants used in the current study, dexmedetomidine 1 μg/kg, dexamethasone 0.1 mg/kg, and magnesium 50 mg added to 0.2% ropivacaine, provide and prolong the postoperative analgesia in pediatric infraumbilical surgeries without undue sedation and adverse effects.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Dr. K. P. Suresh, Scientist (Biostatistics), National Institute of Veterinary Epidemiology and Disease Informatics (NIVEDI), Bengaluru - 560 024, India.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beyaz SG, Tokgöz O, Tüfek A. Caudal epidural block in children and infants: Retrospective analysis of 2088 cases. Ann Saudi Med. 2011;31:494–7. doi: 10.4103/0256-4947.84627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vetter TR, Carvallo D, Johnson JL, Mazurek MS, Presson RG., Jr A comparison of single-dose caudal clonidine, morphine, or hydromorphone combined with ropivacaine in pediatric patients undergoing ureteral reimplantation. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:1356–63. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000261521.52562.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Beer DA, Thomas ML. Caudal additives in children – Solutions or problems? Br J Anaesth. 2003;90:487–98. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lönnqvist PA, Ivani G, Moriarty T. Use of caudal-epidural opioids in children: Still state of the art or the beginning of the end? Paediatr Anaesth. 2002;12:747–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu HH, Wang HT, Jin JJ, Cui GB, Zhou KC, Chen Y, et al. Does dexmedetomidine as a neuraxial adjuvant facilitate better anesthesia and analgesia? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saadawy I, Boker A, Elshahawy MA, Almazrooa A, Melibary S, Abdellatif AA, et al. Effect of dexmedetomidine on the characteristics of bupivacaine in a caudal block in pediatrics. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:251–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.2008.01818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anand VG, Kannan M, Thavamani A, Bridgit MJ. Effects of dexmedetomidine added to caudal ropivacaine in paediatric lower abdominal surgeries. Indian J Anaesth. 2011;55:340–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.84835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiang Q, Huang DY, Zhao YL, Wang GH, Liu YX, Zhong L, et al. Caudal dexmedetomidine combined with bupivacaine inhibit the response to hernial sac traction in children undergoing inguinal hernia repair. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110:420–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El-Feky EM, Abd El-Aziz AA. Fentanyl, dexmedetomidine, dexamethasone as adjuvant to local anesthetics in caudal analgesia in pediatrics: A comparative study. Egypt J Anesth. 2015;31:175–80. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goyal V, Kubre J, Radhakrishnan K. Dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to bupivacaine in caudal analgesia in children. Anesth Essays Res. 2016;10:227–32. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.174468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamal M, Mohammed S, Meena S, Singariya G, Kumar R, Chauhan DS. Efficacy of dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant to ropivacaine in pediatric caudal epidural block. Saudi J Anaesth. 2016;10:384–9. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.177325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choudhary S, Dogra N, Dogra J, Jain P, Ola SK, Ratre B. Evaluation of caudal dexamethasone with ropivacaine for post-operative analgesia in paediatric herniotomies: A randomised controlled study. Indian J Anaesth. 2016;60:30–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.174804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sinha C, Kumar B, Bhadani UK, Kumar A, Kumar A, Ranjan A. A comparison of dexamethasone and clonidine as an adjuvant for caudal blocks in pediatric urogenital surgeries. Anesth Essays Res. 2016;10:585–90. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.186604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girgis K. The effect of adding dexamethasone to bupivacaine on the duration of postoperative analgesia after caudal anesthesia in children. Ain Shams J Anesthesiol. 2014;7:381–7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim EM, Lee JR, Koo BN, Im YJ, Oh HJ, Lee JH. Analgesic efficacy of caudal dexamethasone combined with ropivacaine in children undergoing orchiopexy. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112:885–91. doi: 10.1093/bja/aet484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yousef GT, Ibrahim TH, Khder A, Ibrahim M. Enhancement of ropivacaine caudal analgesia using dexamethasone or magnesium in children undergoing inguinal hernia repair. Anesth Essays Res. 2014;8:13–9. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.128895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim EM, Kim MS, Han SJ, Moon BK, Choi EM, Kim EH, et al. Magnesium as an adjuvant for caudal analgesia in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2014;24:1231–8. doi: 10.1111/pan.12559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson GA, Doyle E. Validation of three paediatric pain scores for use by parents. Anaesthesia. 1996;51:1005–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1996.tb14991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramsay MA, Savege TM, Simpson BR, Goodwin R. Controlled sedation with alphaxalone-alphadolone. Br Med J. 1974;2:656–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5920.656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li SS, Zhang WS, Ji D, Zhou YL, Li H, Yang JL, et al. Involvement of spinal microglia and interleukin-18 in the anti-nociceptive effect of dexmedetomidine in rats subjected to CCI. Neurosci Lett. 2014;560:21–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Degos V, Charpentier TL, Chhor V, Brissaud O, Lebon S, Schwendimann L, et al. Neuroprotective effects of dexmedetomidine against glutamate agonist-induced neuronal cell death are related to increased astrocyte brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression. Anesthesiology. 2013;118:1123–32. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318286cf36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu YL, Zhou LJ, Hu NW, Xu JT, Wu CY, Zhang T, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces long-term potentiation of C-fiber evoked field potentials in spinal dorsal horn in rats with nerve injury: The role of NF-kappa B, JNK and p38 MAPK. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:708–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Ji F, Liang J, He H, Fu Y, Cao M. Inhibition by dexmedetomidine of the activation of spinal dorsal horn glias and the intracellular ERK signaling pathway induced by nerve injury. Brain Res. 2012;1427:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johansson A, Hao J, Sjölund B. Local corticosteroid application blocks transmission in normal nociceptive C-fibres. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1990;34:335–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1990.tb03097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.De Bosscher K, Vanden Berghe W, Haegeman G. The interplay between the glucocorticoid receptor and nuclear factor-kappaB or activator protein-1: Molecular mechanisms for gene repression. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:488–522. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xie W, Liu X, Xuan H, Luo S, Zhao X, Zhou Z, et al. Effect of betamethasone on neuropathic pain and cerebral expression of NF-kappaB and cytokines. Neurosci Lett. 2006;393:255–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.09.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birbicer H, Doruk N, Cinel I, Atici S, Avlan D, Bilgin E, et al. Could adding magnesium as adjuvant to ropivacaine in caudal anaesthesia improve postoperative pain control? Pediatr Surg Int. 2007;23:195–8. doi: 10.1007/s00383-006-1779-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahadian FM, McGreevy K, Schulteis G. Lumbar transforaminal epidural dexamethasone: A prospective, randomized, double-blind, dose-response trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2011;36:572–8. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e318232e843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]