Abstract

Objectives:

To quantitatively evaluate diffusion and perfusion status of lateral pterygoid muscle (LPM) in patients with temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD) by intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) imaging and to correlate with findings on temporomandibular joints (TMJs) by conventional MRI.

Methods:

42 patients with TMD underwent MRI. To assess IVIM parameters, diffusion-weighted imaging was obtained by spin-echo-based single-shot echoplanar imaging. Regions of interest were created on all diffusion-weighted images of the superior belly of the lateral pterygoid (SLP) and inferior belly of the lateral pterygoid (ILP) at b-values 0–500 s mm−2. Then, IVIM parameters, diffusion (D) and perfusion (f) were calculated using biexponential fittings. The correlation of these values with conventional MRI findings on TMJs was investigated.

Results:

For SLP, the f parameter in TMJs with anterior disc displacement without reduction was significantly higher than that in normal ones (p = 0.015). It was also significantly higher in TMJs with joint effusion than in those without (p = 0.016). On the other hand, for both SLP and ILP, the D parameter significantly increased in TMJs with osteoarthritis compared with those without (p = 0.015 and p = 0.022, respectively).

Conclusions:

Pathological changes of LPM in patients with TMD may be quantitatively evaluated by IVIM parameters.

Keywords: diffusion-weighted MRI, diagnostic imaging, masticatory muscles, pterygoid muscle, temporomandibular joint disorders

Introduction

The lateral pterygoid muscle (LPM) is one of the masticatory muscles, consisting of two bellies: the superior belly of the lateral pterygoid (SLP) and the inferior belly of the lateral pterygoid (ILP).1 The muscle fibres of the LPM mostly insert into the condyle at the pterygoid fovea, whereas some of the SLP fibres insert into the articular disc.2,3 The two bellies, SLP and ILP, work as a reciprocal pattern. The ILP is active during jaw opening, protrusion and lateral movement to the contralateral side, while the SLP, in normal functions, is active during jaw closing and lateral movement to the ipsilateral side.4 It is well known that SLP activity increases during clenching, which implies a disc-stabilized function.4,5 Owing to the close relationship between the LPM and the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD) is associated with LPM dysfunctions such as hyperactivity, hypoactivity or lack of muscle coordination.4,6,7 Several studies reported pathological changes of the LPM in patients with TMD by MRI. However, these studies were all conducted using MR images obtained by conventional MRI.8–10

Intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) MRI, which was first reported by Bihan et al,11 is one of the diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) techniques. It can estimate both water diffusion and blood perfusion of the biologic tissue separately by measuring MR signal intensities from multiple b-values and biexponential fitting. Recently, IVIM is widely used to investigate several diseases throughout the body including brain, hepatic, renal, musculoskeletal and head and neck diseases.12–14 Concerning the masticatory muscles, it was reported that IVIM could demonstrate increasing of blood perfusion of the masseter and the medial pterygoid muscles during clenching.15 However, there have been no studies to evaluate the pathological conditions of the LPM related to TMDs by IVIM.

The aims of this study were to quantitatively evaluate the LPM changes in patients with TMDs by IVIM and to correlate these with conventional MRI findings on TMJs.

Methods and materials

Subjects

The protocol of this prospective MRI study received approval from the institutional review board of our university, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients before MRI examination. 45 consecutive patients, who were referred to Oral and Maxillofacial Radiology Clinic for receiving MRI examina-tion of TMJs from October 2015 to February 2016, were registered in this study. Among them, three patients were excluded because of severe image distortions due to motion or susceptibility artefacts on the DW images.

MRI techniques

All MRI examinations were performed using a 3.0-T MRI scanner (Magnetom Spectra; Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany), with a 4-channel special purpose coil for conventional MRI and a 16-channel head and neck coil for DWI. The conventional MRI protocol for TMJ was as follows: in the closed mouth position, oblique sagittal and oblique coronal proton density-weighted spin-echo images [repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE), 3000 ms/21 ms] and oblique sagittal T2 weighted turbo spin-echo images with fat suppression by chemical-shift selective saturation (TR/TE, 4000 ms/88 ms) were obtained. In the open mouth position, oblique sagittal proton density-weighted images were obtained (TR/TE, 2000 ms/21 ms). The imaging parameters of all images were as follows: field of view (FOV), 100 × 100 mm; matrix, 256 × 205 interpolated to 512 × 410; slice thickness, 3 mm with gap of 0.3 mm; voxel size, 0.2 × 0.2 × 3.0 mm. After conventional MRI, three-dimensional (3D) T1 weighted (T1W) images were obtained using sampling perfection with application optimized contrasts using different flip angle evolutions (SPACE) sequence [TR/TE, 650 ms/20 ms; number of slices, 88; FOV, 182 × 182 mm; matrix, 192 × 192 interpolated to 384 × 384; slice thickness, 0.5 mm; voxel size, 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 mm; iPAT, 2 Generalized Autocalibrating Partially Parallel Acquisitions (GRAPPA)]. The 3D T1W images were used to select the planes showing the maximal area of the SLP and the ILP. After that, DWI data were obtained by spin-echo-based single-shot echoplanar imaging with fat suppression by short tau inversion recovery [TR/TE/inversion time, 6800 ms/72 ms/250 ms; FOV, 230 × 220 mm; matrix, 92 × 88 interpolated to 184 × 176; voxel size, 1.25 × 1.25 × 3 mm; slice thickness, 3 mm without gap; number of average, three; iPAT, 3 GRAPPA]. Motion-probing gradients for DWI were applied in three-scan trace diffusion mode with 8 b-values (0, 50, 100, 150, 200, 300, 400 and 500 s mm−2).

Evaluation of conventional MR images

All conventional MR images were evaluated by two oral radiologists, who had 4 years' and more than 10 years' experience in interpreting MR images of TMJs, for the articular disc displacement, the presence or absence of joint effusion and the presence or absence of osteoarthritis including osteophyte, condyle erosion and subchondral osteosclerosis. The articular disc displacement was classified into three categories: normal disc (ND) position, anterior disc displacement with reduction (ADWR) and anterior disc displacement without reduction (ADWOR).

Intravoxel incoherent motion data analysis

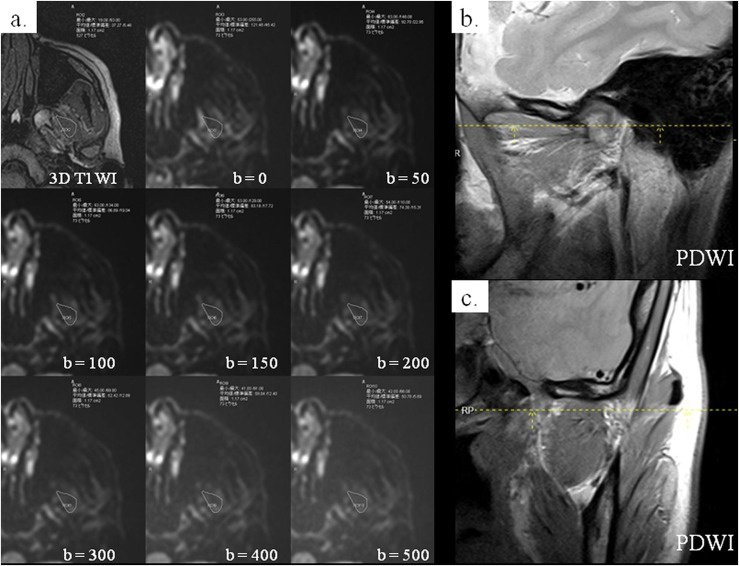

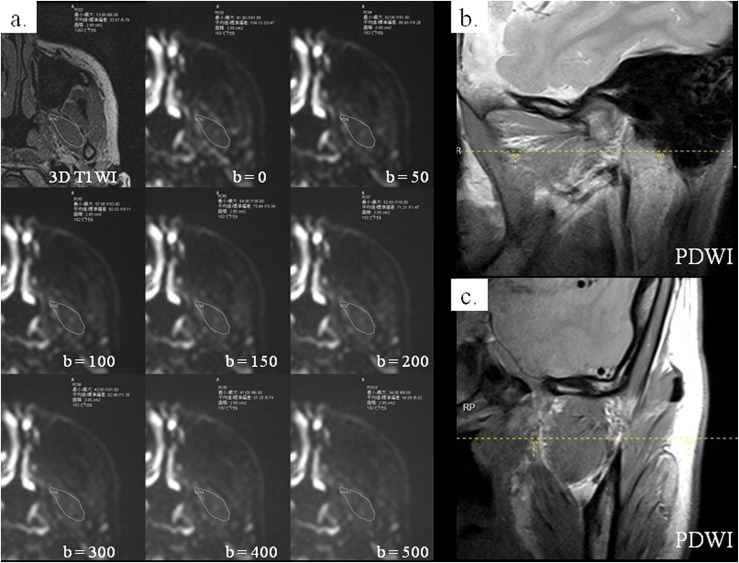

Using conventional MR images as the references to identify the contour of the SLP and ILP, the same two radiologists selected the axial 3D T1W image showing the maximal area of each of the two bellies. On the selected images, they drew regions of interest (ROIs) on the SLP and the ILP by consensus. The ROI was drawn by freehand to include the whole area of the SLP or ILP. After that, the ROI was superimposed on all the DW images at the same level with b-values of 0–500 s mm−2 to measure signal intensities (Figures 1 and 2). The mean ROI areas of the SLP and ILP were 2.14 ± 0.64 cm2 and 2.54 ± 0.65 cm2, respectively.

Figure 1.

A 33-year-old female: on the axial three-dimensional (3D) T1 weighted image (T1WI) showing the maximal area of the superior belly of the lateral pterygoid muscle (SLP), the region of interest (ROI) including the whole SLP was drawn (a: upper left image). The ROI was superimposed on eight diffusion-weighted images of the same level with different b-values, and signal intensity was measured on each image (a: the other images). Parasagittal (b) and paracoronal (c) proton density-weighted images (PDWIs) were used to confirm the location of SLP (dashed lines).

Figure 2.

The same patient as in Figure 1: on the axial three-dimensional (3D) T1 weighted image (T1WI) showing the maximal area of the inferior belly of the lateral pterygoid (ILP), the region of interest (ROI) including the whole ILP was drawn (a: upper left image). The ROI was superimposed on eight diffusion-weighted images of the same level with different b-values, and signal intensity was measured on each image (a: the other images). Parasagittal (b) and paracoronal (c) proton density-weighted images (PDWIs) were used to confirm the location of ILP (dashed lines).

The IVIM parameters were estimated for both SLP and ILP. The relation between signal intensities and b-values (0–500 s mm−2) was quantitatively analyzed according to the IVIM model:

where S0 is the signal intensity at b = 0 s mm−2, Sb is the signal intensity at given b-values (50–500 s mm−2), f is the perfusion fraction, D is pure molecular diffusion and D* is the diffusion coefficient for microcirculation. The equation was determined on the basis of the segmented fitting method. That is, the effects of D* on signal intensity can be neglected at high b-values (>200 s mm−2). Therefore, the D parameter can be calculated from the monoexponential fitting of b-values ≥200 s mm−2 as follows:

where Sb1 and Sb2 indicate the signal intensities of the two different b-values. Then, the f parameter can be calculated by the following equation:

where Sint is the intercept between the y-axis and a logarithmic linear regression estimated at b-values 200–500 s mm−2. All algorithms were fitted with software (IGOR Pro, Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR).

For all patients, the two IVIM parameters (D and f) of SLP and ILP were obtained. The correlation of these values with conventional MRI findings on TMJs was investigated.

Statistical analysis

To compare the IVIM parameters of LPM among TMJs with different MR findings, the Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis test with Bonferroni correction were performed. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS® v. 22.0 software for Windows (IBM Corp., New York, NY; formerly SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

A total of 84 TMJs from 42 patients were included in this study. There were 11 males (mean age, 47.1 years; range, 25–77 years) and 31 females (mean age, 46.7 years; range, 22–78 years). The MRI characteristics of the 84 TMJs are shown in Table 1. Regarding the disc position, ADWR and ADWOR were found in 26 (31%) TMJs and 26 (31%) TMJs, respectively. Meanwhile, joint effusion occurred in 30 (36%) TMJs and there was osteoarthritis in 22 (26%) TMJs.

Table 1.

Summary of subject demographic data and MRI characteristics

| Subject demographics | Number of patients | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 42 | (100) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 11 | (26) |

| Female | 31 | (74) |

| Age (years) | Mean | Range |

| Male | 47.1 | (25–77) |

| Female | 46.7 | (22–78) |

| MRI characteristics | Number of TMJs | (%) |

| Total | 84 | (100) |

| Disc position | ||

| Within normal limit (ND) | 32 | (38) |

| ADWR | 26 | (31) |

| ADWOR | 26 | (31) |

| Joint effusion | ||

| Absent | 54 | (64) |

| Present | 30 | (36) |

| Osseous change | ||

| Absent | 62 | (74) |

| Present | 22 | (26) |

ADWOR, anterior disc displacement without reduction; ADWR, anterior disc displacement with reduction ND, normal disc; TMJ, temporomandibular joint.

Quantitative analysis of superior belly of the lateral pterygoid and inferior belly of the lateral pterygoid by intravoxel incoherent motion parameters

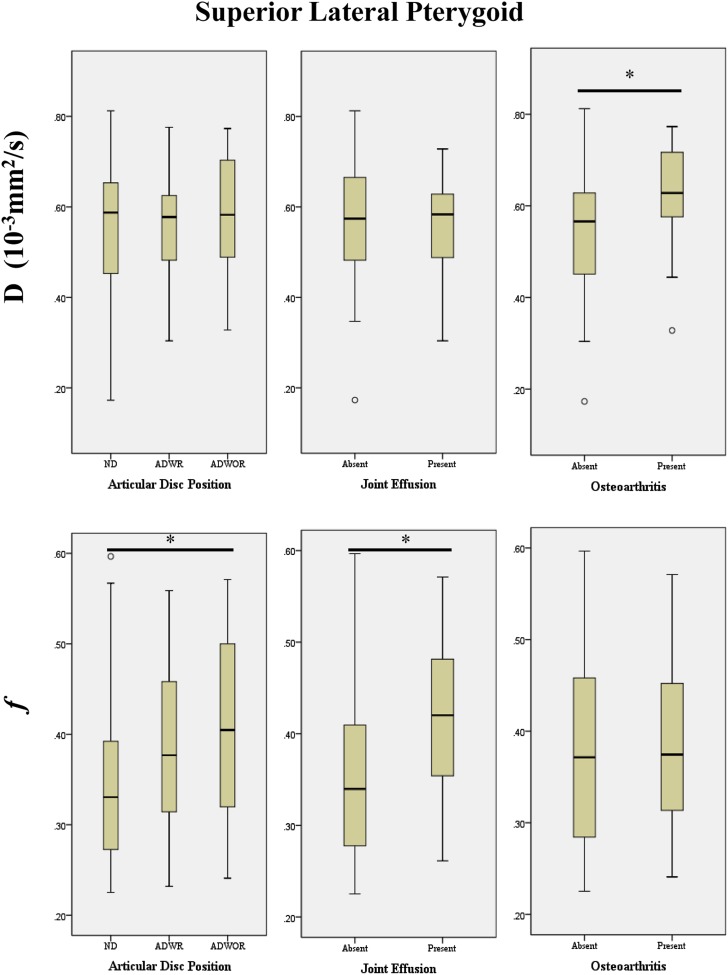

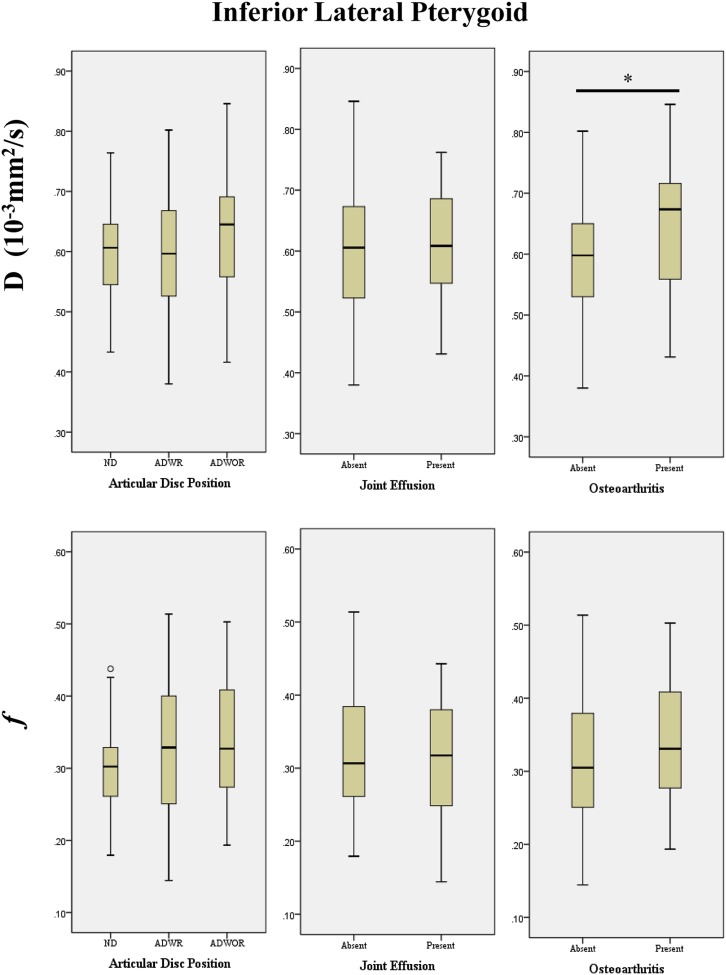

The water diffusion and blood perfusion of SLP and ILP were quantitatively analyzed by IVIM parameters, D and f, respectively. The relationship between these parameters and MRI characteristics is shown in Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3.

Box plots demonstrating the relationship between the intravoxel incoherent motion parameters (D and f) of the superior lateral pterygoid muscle and the MRI findings of the temporomandibular joints for the articular disc position, joint effusion and osteoarthritis (*p < 0.05). ADWOR, anterior disc displacement without reduction; ADWR, anterior disc displacement with reduction ND, normal disc.

Figure 4.

Box plots demonstrating the relationship between the intravoxel incoherent motion parameters (D and f) of the inferior lateral pterygoid muscle and the MRI findings of the temporomandibular joints for the articular disc position, joint effusion and osteoarthritis (*p < 0.05). ADWOR, anterior disc displacement without reduction; ADWR, anterior disc displacement with reduction ND, normal disc.

For SLP, the D parameter was significantly higher in TMJs with osteoarthritis than that in those without (median: 0.63 × 10−3 mm2 s−1 vs 0.57 × 10−3 mm2 s−1; p = 0.015), whereas, the f parameter in TMJs with ADWOR was significantly higher than that in ND (0.40 × 10−3 mm2 s−1 vs 0.33 × 10−3 mm2 s−1; p = 0.015). It was also significantly higher in TMJs with joint effusion than in those without (0.42 vs 0.34; p = 0.016).

On the other hand, for ILP, the D parameter in TMJs with osteoarthritis was significantly higher than that in those without (0.67 × 10−3 mm2 s−1 vs 0.60 × 10−3 mm2 s−1; p = 0.022), which was similar to the result for SLP. However, the presence of ADWR/ADWOR or joint effusion did not increase either the f or D parameters.

Discussion

IVIM is a DWI technique that uses multiple b-values and biexponential fitting. It allows the measurement of water molecular diffusion (D parameter) and blood perfusion fraction (f parameter) in the microvascular system separately.11 To our knowledge, this is the first study that quantitatively evaluated the pathological conditions of LPM in patients with TMD by IVIM. In our study, the pathological changes of SLP and ILP in TMDs could be detected as alterations in the IVIM parameters. In SLP, the f parameter significantly increased in TMJs with ADWOR compared with ND. The increase may reflect high blood volume in the capillaries, implying inflammation of the SLP. In fact, the increase in the f parameter was relatively small in TMJs with ADWR. These results may also indicate that changes in the f parameter in SLP were related to the severity of anterior disc displacement. Regarding ILP, significant changes in the f parameter were not found regardless of disc position. The difference between the SLP and ILP was possibly due to the fact that only the SLP inserted into the articular disc.2,3 Yang et al9 evaluated conventional MR images of patients with ADWOR and found that morphological changes were more frequent in SLP than in ILP. According to their study, morphological changes in SLP alone, ILP alone and both were found in 35.8%, 9.7% and 25.2%, respectively. The type of the muscle changes included hypertrophy, contracture and atrophy. Taskaya-Yilmaz et al8 also reported LPM changes in patients with ADWOR, which were more frequent in SLP than in ILP. Finden et al10 performed a quantitative analysis of LPM on conventional MRI and reported that pathological changes of SLP in patients with TMDs were shown as alterations of MR signal intensity. Further, they showed that the signal intensity of SLP increased approximately linearly with the severity of disc derangement: ND, ADWR and ADWOR. The results of those studies were consistent with ours.

Similarly to TMJs with ADWOR, an increase of the f parameter in SLP was found in those with joint effusion. The level of proinflammatory cytokines and cytokine receptors in synovial fluid has been reported as increased in patients with joint effusion.16,17 Further, some studies reported that the presence of joint effusion reflected synovitis and was clinically related to TMJ pain.18,19 Thus, the increase in the f parameter related to joint effusion was also considered as reflecting the SLP inflammation.

TMJ osteoarthritis including abrasion of articular surface, subchondral sclerosis, osteophyte and the reduction of joint space is considered to occur in the late stage of TMDs and clinically causes limitation of mandibular movement. Osteoarthritis induces reduction of muscle function, leading to weakening and atrophy of the muscles.20–22 Our study showed that the D parameter in both SLP and ILP was significantly increased in TMJs with osteoarthritis. On the other hand, in either SLP or ILP, the f parameter did not change. These results may reflect the expansion of extracellular space in LPM due to atrophic changes. An experimental study using rabbits showed that atrophic muscles were likely to have an increased apparent diffusion coefficient value.12

We consider that pathological changes of ILP may occur secondary to those of SLP. Lafreniere et al23 demonstrated by electromyography that ILP function became abnormal after the loss of SLP function. Thus, pathological changes of the LPM seem to occur in both bellies, first in SLP and followed by in ILP. In our study, the changes of the IVIM parameter in the early stage of TMD (without osteoarthritis) were found in SLP, but not in ILP. The parameter in ILP changed only in the later stage of TMD with bone destruction of TMJs.

There have been few studies that evaluated the conditions of masticatory muscles by IVIM parameters. To our knowledge, the only exception was the study by Sasaki et al15 that assessed the perfusion and diffusion of masticatory muscles of healthy volunteers by IVIM. According to their study, the D and f parameters of LPM during resting were around 1.00 × 10−3 mm2 s−1 and 0.27 (median), respectively. The D parameter in their study was relatively higher than that in ours, whereas the f parameters were similar. This discrepancy may be caused by the difference in study population and DWI protocol. Concerning the latter, the number and range of b-values have been reported as influencing the value of the IVIM parameters.24

This study is one of the early trials of applying IVIM to investigate the pathological condition of LPM in patients with TMD quantitatively. We supposed that the changes of perfusion and diffusion might indicate the pathological condition such as inflammation and atrophic change of the muscle. Further, our results supported that TMD might relate pathological changes of LPM.

In the clinical settings, the muscle condition is usually evaluated by performing muscle palpation. However, it is often difficult to evaluate LPM using this method owing to its anatomically deep position. In such cases, functional manipulation is the only method for assessing whether it is a source of pain.1 We expect that IVIM is a non-invasive and useful technique with clinical benefits for evaluating the muscle condition directly and for the follow-up study after the treatment of TMD.

Our study had some limitations. First, the severity of the clinical symptoms of the patients, including joint pain and the mouth opening limitation, were not evaluated. To investigate the relationship between the clinical symptoms and IVIM parameters, further studies will be needed. Second, we obtained DW images with b-values ranging from 0 to 500 s mm−2. We did not use higher b-values such as 800 s mm−2, 1000 s mm−2 and 1500 s mm−2 to minimize the geometric distortion caused by susceptibility, chemical shift and N/2 artifacts, which was often seen in the head and neck region. However, it is not certain whether the DWI methods in our study were optimal to obtain the IVIM parameters of LPM.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the pathological conditions of LPM in patients with TMD may be quantitatively evaluated by IVIM. The pathological changes were more frequently found in SLP than in ILP.

Contributor Information

Supak Ngamsom, Email: supak.black@gmail.com, supaorad@tmd.ac.jp.

Shin Nakamura, Email: shin.orad@tmd.ac.jp.

Junichiro Sakamoto, Email: sakajun.orad@tmd.ac.jp.

Shinya Kotaki, Email: kotaki.orad@tmd.ac.jp.

Akemi Tetsumura, Email: akemi.orad@tmd.ac.jp.

Tohru Kurabayashi, Email: kura.orad@tmd.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Okeson JP. Management of temporomandibular disorders and occlusion. 7th edn. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998. p. 504. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakaguchi-Kuma T, Hayashi N, Fujishiro H, Yamaguchi K, Shimazaki K, Ono T, et al. An anatomic study of the attachments on the condylar process of the mandible: muscle bundles from the temporalis. Surg Radiol Anat 2016; 38: 461–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00276-015-1587-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilkinson TM. The relationship between the disk and the lateral pterygoid muscle in the human temporomandibular joint. J Prosthet Dent 1988; 60: 715–24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3913(88)90406-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahan PE, Wilkinson TM, Gibbs CH, Mauderli A, Brannon LS. Superior and inferior bellies of the lateral pterygoid muscle EMG activity at basic jaw positions. J Prosthet Dent 1983; 50: 710–18. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3913(83)90214-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang MQ, Yan CY, Yuan YP. Is the superior belly of the lateral pterygoid primarily a stabilizer? An EMG study. J Oral Rehabil 2001; 28: 507–10. doi: https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2842.2001.00703.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibbs CH, Mahan PE, Wilkinson TM, Mauderli A. EMG activity of the superior belly of the lateral pterygoid muscle in relation to other jaw muscles. J Prosthet Dent 1984; 51: 691–702. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3913(84)90419-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Juniper RP. Temporomandibular joint dysfunction: a theory based upon electromyographic studies of the lateral pterygoid muscle. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1984; 22: 1–8. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0266-4356(84)90001-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taskaya-Yilmaz N, Ceylan G, Incesu L, Muglali M. A possible etiology of the internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint based on the MRI observations of the lateral pterygoid muscle. Surg Radiol Anat 2005; 27: 19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang X, Pernu H, Pyhtinen J, Tiilikainen PA, Oikarinen KS, Raustia AM. MR abnormalities of the lateral pterygoid muscle in patients with nonreducing disk displacement of the TMJ. Cranio 2002; 20: 209–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finden SG, Enochs WS, Rao VM. Pathologic changes of the lateral pterygoid muscle in patients with derangement of the temporomandibular joint disk: objective measures at MR imaging. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2007; 28: 1537–9. doi: https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A0590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Bihan D, Breton E, Lallemand D, Grenier P, Cabanis E, Laval-Jeantet M. MR imaging of intravoxel incoherent motions: application to diffusion and perfusion in neurologic disorders. Radiology 1986; 161: 401–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.161.2.3763909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holl N, Echaniz-Laguna A, Bierry G, Mohr M, Loeffler JP, Moser T, et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI of denervated muscle: a clinical and experimental study. Skeletal Radiol 2008; 37: 1111–17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00256-008-0552-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iima M, Le Bihan D. Clinical intravoxel incoherent motion and diffusion MR imaging: past, present, and future. Radiology 2016; 278: 13–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2015150244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sakamoto J, Imaizumi A, Sasaki Y, Kamio T, Wakoh M, Otonari-Yamamoto M, et al. Comparison of accuracy of intravoxel incoherent motion and apparent diffusion coefficient techniques for predicting malignancy of head and neck tumors using half-Fourier single-shot turbo spin-echo diffusion-weighted imaging. Magn Reson Imaging 2014; 32: 860–6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2014.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasaki M, Sumi M, Van Cauteren M, Obara M, Nakamura T. Intravoxel incoherent motion imaging of masticatory muscles: pilot study for the assessment of perfusion and diffusion during clenching. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2013; 201: 1101–7. doi: https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.12.9729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaneyama K, Segami N, Yoshimura H, Honjo M, Demura N. Increased levels of soluble cytokine receptors in the synovial fluid of temporomandibular joint disorders in relation to joint effusion on magnetic resonance images. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010; 68: 1088–93. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2009.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Segami N, Miyamaru M, Nishimura M, Suzuki T, Kaneyama K, Murakami K. Does joint effusion on T2 magnetic resonance images reflect synovitis? Part 2. Comparison of concentration levels of proinflammatory cytokines and total protein in synovial fluid of the temporomandibular joint with internal derangements and osteoarthrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2002; 94: 515–21. doi: https://doi.org/10.1067/moe.2002.126697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Segami N, Nishimura M, Kaneyama K, Miyamaru M, Sato J, Murakami KI. Does joint effusion on T2 magnetic resonance images reflect synovitis? Comparison of arthroscopic findings in internal derangements of the temporomandibular joint. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001; 92: 341–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1067/moe.2001.117808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi T, Nagai H, Seki H, Fukuda M. Relationship between joint effusion, joint pain, and protein levels in joint lavage fluid of patients with internal derangement and osteoarthritis of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999; 57: 1187–93; discussion 1193–4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-2391(99)90483-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Bont LG, Stegenga B. Pathology of temporomandibular joint internal derangement and osteoarthrosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1993; 22: 71–4. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80805-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rando C, Waldron T. TMJ osteoarthritis: a new approach to diagnosis. Am J Phys Anthropol 2012; 148: 45–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ajpa.22039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilkes CH. Internal derangements of the temporomandibular joint. Pathological variations. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1989; 115: 469–77. doi: https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.1989.01860280067019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lafreniere CM, Lamontagne M, el-Sawy R. The role of the lateral pterygoid muscles in TMJ disorders during static conditions. Cranio 1997; 15: 38–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemke A, Stieltjes B, Schad LR, Laun FB. Toward an optimal distribution of b values for intravoxel incoherent motion imaging. Magn Reson Imaging 2011; 29: 766–76. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2011.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]