Abstract

Objectives

The aim of study was to compare the accuracy between rectal water contrast transvaginal ultrasound (RWC-TVS) and double-contrast barium enema (DCBE) in evaluating the bowel endometriosis presence as well as its extent.

Design and setting

198 patients at reproductive age with suspicious bowel endometriosis were included. Physicians in two groups specialised at endometriosis performed RWC-TVS as well as DCBE before laparoscopy and both groups were blinded to other groups’ results. Findings from RWC-TVS or DCBE were compared with histological results. The severity of experienced pain severity through RWC-TVS or DCBE was assessed by an analogue scale of 10 cm.

Results

In total, 110 in 198 women were confirmed to have endometriosis nodules in the bowel by laparoscopy as well as histopathology. For bowel endometriosis diagnosis, DCBE and RWC-TVS demonstrated sensitivities of 96.4% and 88.2%, specificities of 100% and 97.3%, positive prediction values of 100% and 98.0%, negative prediction values of 98.0% and 88.0%, accuracies of 98.0% and 92.4%, respectively. DCBE was related to more tolerance than RWC-TVS.

Conclusions

RWC-TVS and DCBE demonstrated similar accuracies in the bowel endometriosis diagnosis; however, patients showed more tolerance for RWC-TVS than those with DCBE.

Keywords: bowel endometriosis, double-contrast barium enema, diagnosis, rectal water contrast transvaginal ultrasound

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first comparison of the accuracy between rectal water contrast transvaginal ultrasound (RWC-TVS) and double-contrast barium enema (DCBE) in the diagnosis of bowel endometriosis.

This study demonstrated RWC-TVS as a very reliable technique to determine the bowel endometriosis presence and extent and it has similar accuracy to that of DCBE.

We demonstrate that DCBE is related to more tolerance than RWC-TVS.

This study requires a larger sample once suitable participants become available.

Introduction

Bowel endometriosis influences 4%–37% patients of endometriosis.1 Lesions in intestinal endometriosis have variable sizes.2 Endometriosis nodules of small sizes locate in the bowel serosal surface hardly causing symptoms and treatments are not required.2 Endometriosis nodules of larger sizes may infiltrate the wall of bowel and cause some gastrointestinal complaints such as diarrhoea, dyschezia, constipation, intestinal cramping and abdominal bloating.1 3 The symptoms mimic acute bowel syndrome. The symptoms with bowel endometriosis mainly are non-specific, usually causing misdiagnosis or diagnosis delay.4 Physical examinations may suggest rectovaginal endometriosis presence. However, the accuracy is poor in identifying rectosigmoid nodules.5 6

Until recently, endometriosis diagnosis ultrasound was limited to patients with ovarian endometriosis. Other imaging methods were used for assessing bowel endometriosis, such as rectal endoscopic ultrasound, double-contrast barium enema (DCBE), transvaginal ultrasound (TVS), MRI, virtual colonoscopy and multidetector CT enema (MDCT-e).7–10 TVS, as a reliable and non-invasive method for assessing bowel endometriosis presence and extent.11 Rectosigmoid nodules identification may be facilitated by saline injection through a catheter going into the rectum through rectal water contrast TVS (RWC-TVS), assessment of infiltration depth of endometriosis on intestinal wall as well as estimation of stenosis degree in the bowel lumen. Yet, no studies have compared the accurateness between DCBE and RWC-TVS in rectosigmoid endometriosis diagnosis.4 12 13

The diagnosis of bowel endometriosis presence and extent before the surgery is necessary for making a decision on whether the operation is required as well as planning the operation procedure with colorectal surgeons.14 Preoperational knowledge of intestinal endometriosis nodules size, number, nodule infiltration depth on the wall of intestine, as well as bowel lumen stenosis degree allows for making best decision on whether the surgery is requisite and whether nodulectomy or bowel segmental resection should be chosen.15 16

Additionally, preoperational determining of bowel endometriosis extent allows for that the surgeon informs the patient of the benefits as well as potential complications during the operation procedure to be performed. In fact, evolution or complications of the symptoms in digestive system postsurgery may be different for patients experiencing nodulectomy and segmental resection. In this study, we assessed and compared the diagnosis accuracy between DCBE and RWC-TVS for evaluating the bowel endometriosis presence and extent.

Materials and methods

Study population

This study was conducted from May 2012 to Aug 2016. Patients at the reproductive ages with laparoscopy scheduled for intestinal endometriosis suspicious clinical examination or symptoms were recruited as participants in this study. During this period, it is required by imaging workup that DCBE and RWC-TVS were conducted in the patients with suspicious bowel endometriosis. Institutional Review Board of Tianjin First Center Hospital approved the protocols involved in this study before initialisation of the study. All patients enrolled in this study signed the written consent form. Inclusion criteria of this study were: suspicious deep pelvic endometriosis, at reproductive age, gastrointestinal symptoms likely being caused by the bowel endometriosis, desire for complete surgical endometriosis excision. Exclusion criteria of this study were: precedent bilateral ovariectomy, radiological diagnosis of bowel endometriosis, examination of barium radiology, colorectal surgery, hepatic or renal failure, suggestive intolerance for iodinated contrast medium or refuse for DCBE or psychiatric disorders.

Symptoms were investigated systematically throughout the study and were documented in a database. The existence of deep dyspareunia, dysmenorrhoea, dyschezia and non-menstrual pelvic was examined and the symptom intensities were evaluated of all patients by a 10 cm visual analogue scale (VAS), in which left edge indicated no pain and right extremity presented maximum pain. Whether the following gastrointestinal symptoms were presented was determined: irritable bowel syndrome of diarrhoea-predominance, passage of the stool mucus, irritable bowel syndrome of constipation-predominance, abdominal bloating rectal bleeding and intestinal cramping. A questionnaire of symptom analogue scale was used to estimate every gastrointestinal symptom severity.

The results of DCBE and RWC-TVS were compared with pathologic and surgical findings. The radiologists conducting DCBE as well as the gynaecologists conducting TVS were both blinded to the results of others. They were also blinded to clinical data and only knew that the intestinal endometriosis presence was suspected. All the patients underwent laparoscopy, which was within 1 month after completion of investigations for diagnosis. Intestinal endometriosis disease was defined by the minimum infiltration of muscularis propria. Endometriosis foci on bowel serosa were peritoneal instead of bowel endometriosis. This study investigated the accurateness of RWC-TVS and DCBE in assessing the bowel endometriosis presence, evaluating the number and the size for nodules of bowel endometriosis as well as determining the existence of peritoneal endometriosis with only intestinal serosa being infiltrated.

Technique of rectal water contrast transvaginal ultrasound

Two physicians conducted all of the examinations in line with a standardised procedure.10 RWC-TVS was conducted by using a Voluson E6 machine connected with a transvaginal transducer. Once the transducer was placed in the vagina, a 6 mm flexible catheter was inserted in rectal lumen with a distance of 15 cm to the anus through the anus. To facilitate of the catheter passage, a gel containing lidocaine was applied. A 50 mL syringe connected with the catheter and warm saline solution then was injected to the rectum as well as the sigmoid with ultrasonic control. The saline solution amount for showing the rectosigmoid varied from 100 to 350 mL, based on the intestinal wall dispensability. One hundred millilitres saline solution was slowly and continuously instilled at the procedure beginning, and the rest solution was instilled if requested by ultrasound. When the saline solution was not being infused during the ultrasound, Klemmer forceps attached to the catheter was placed to prevent backflow in the catheter. No significant saline solution leakage in the space was seen between catheter and anus. Before, during as well as after saline injection, images were taken. Bowel endometriosis was shown ultrasonographically as solid, hypoechoic, nodular lesions, adjacent to or penetrating the wall of the intestine. Hyperechoic foci sometimes may present inside the lesion. Intestinal distension permits defining the intestinal nodule limits and various layers within rectal wall in particular so as to estimate infiltration depth. The submucosa and intestinal serosa are hyperechoic. Two layers in muscularis propria were shown as strips with hypoechoic divided by a thin hyperechoic line. Muscularis mucosa appears hypoechoic, and interface connecting the lumen and mucosal layer appears hyperechoic (figure 1). Infiltration of rectal endometriosis was verified by that hypoechoic nodules penetrate the wall of the intestine and in general muscularis mucosa was thickened by the hypoechoic nodules. Two different ultrasound signs were normally used to define this condition (figure 2).

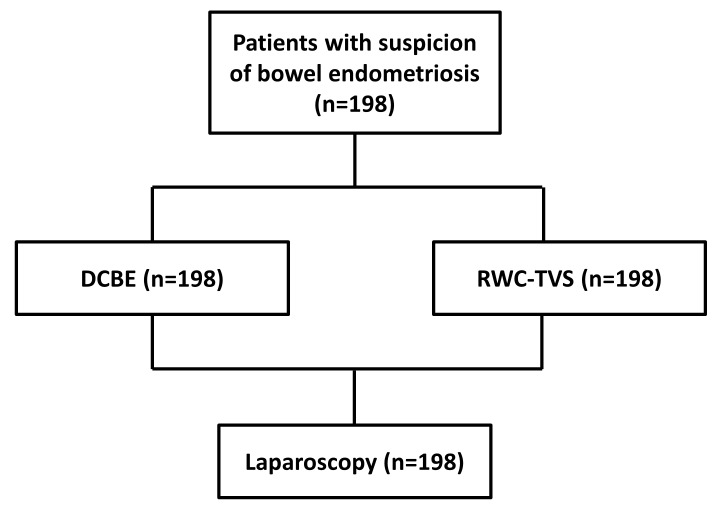

Figure 1.

Rectal water contrast transvaginal ultrasonography image showing a rectal endometriotic nodule thickening the muscularis mucosa (arrowhead). The rectal lumen is distended by saline solution (WC).

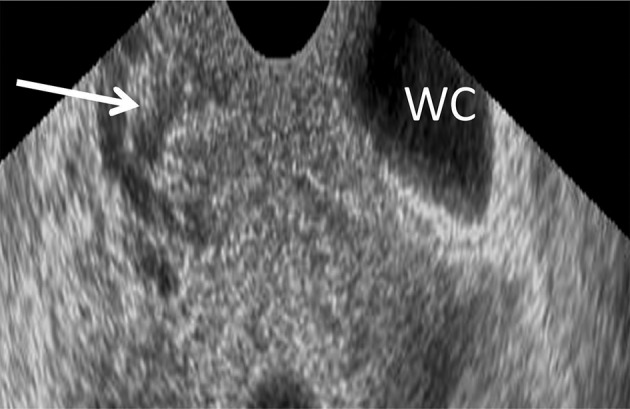

Figure 2.

Rectal water contrast transvaginal ultrasonography image showing a rectal endometriotic nodule (arrow) with largest longitudinal diameter of 2.7 infiltrating the intestinal submucosa.

DCBE

All procedures by DCBE were conducted by a motorised and tilting table to perform radiological and fluoroscopic examination. For preparation, patients kept low-residue diet in a 1-day period before the examination in order to keep enteric content fluid. Then examination was conducted after the intramuscular administration of 20 mg (1 ampoule) scopolamine to induce colonic hypotonia. The presence of bowel endometriosis was diagnosed on DCBE when the bowel lumen was narrowed at any level from the sigmoid to the anus (extrinsic mass effect) in association with crenulation of the mucosa and/or speculation of contour (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Double-contrast barium enema showing the effect of a large endometriotic nodule on the surface of the sigmoid colon.

Examinations tolerability

Immediately after every examination, patients rated the level of discomfort experienced during DCBE as well as RWC-TVS using a 10 cm VAS. Mild pain was scored <2, moderate pain was scored ≥2 and severe pain was scored >5.

Operation and histological assessment

The surgeons carefully examined the results and images by DCBE and RWC-TVS prior to the laparoscopy. Although the rectosigmoid endometriosis diagnosis and treatment were dependent on the laparoscopic findings, operational procedures were conducted through laparoscope evaluated by the team composed of colorectal as well as gynaecological surgeons with lots of experience in the bowel endometriosis and pelvic treatment. In all cases, the rectum and sigmoid colon were examined systematically to confirm the endometriosis lesion presence after enough adhesiolysis. The lesions of bowel endometriosis were removed via intestinal resection, which happened in the cases of a single lesion with >3 cm diameter or infiltrating 50% or more of the intestinal wall circumference, or at least three lesions infiltrating muscular layer. In all the other bowel endometriosis cases, disk resection of partial-thickness or full-thickness was conducted. Excision by shaving was conducted for intestinal lesions with simply the serosal layer of bowel wall infiltrated. All of the visible lesions that were suspicious endometriosis were removed and then sent for histology examination according to our clinical protocol.

The excised specimens were assessed by histology, and the infiltration depth of endometriosis nodules of bowel wall was assessed. In nodulectomy cases, specimens were oriented macroscopically along intestinal wall (from serosa to the mucosa) and cut to macrosections with 2 mm thickness. From every macrosection tissue, blocks at 1.5 cm length were attained in various numbers based on the lesion size, and sections at 5 µm were attained for microscopically evaluation from each tissue. In bowel resection cases specimens were longitudinally opened through their entire lengths. Two millimetres bowel wall longitudinal bands were dissected. The bands were embedded in the tissue blocks, and sections of 5 µm were attained for evaluation by microscopy.

Statistical analysis

Sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value (NPV) and positive predictive value (PPV) were assessed for both RWC-TVS and DCBE. Each test diagnostic value was also measured by negative likelihood ratio (LR–) and positive likelihood ratio (LR+). Efficacy parameters at 95% CIs were calculated. McNemar’s test using Yates continuity correction was used to compare accuracy of RWC-TVS and DCBE in the intestinal endometriosis diagnosis. McNemar’s test was used to compare the patient number in which the rectosigmoid nodule numbers were identified by RWC-TVS and DCBE correctly. Accuracy of nodule size assessment with these imaging methods was evaluated by subtracting nodule size assessed by these methods from the nodule size assessed by histology. Non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was applied to compare pain intensity of patients with RWC-TVS or DCBE. χ2 test was used to compare pain type (mild pain, moderate pain or severe pain). Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was applied to define whether correlation between pain intensity of patients experiencing these two techniques exists. SPSS software was used for data analysis. p<0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Study population

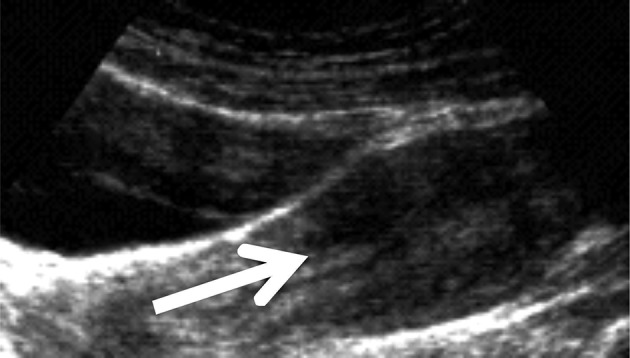

Totally, 198 patients participated in this study and all underwent surgeries were involved in the study (figure 4). The major demographic characteristics in this study are displayed in table 1. The pain intensities as well as gastrointestinal symptoms are shown in table 2.

Figure 4.

Flow chart of the study. DCBE, double-contrast barium enema; RWC-TVS, rectal water contrast transvaginal ultrasonography.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population

| n=198 | |

| Age (year) | 32.7±4.9 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.4±2.4 |

| Previous surgery for endometriosis | 78 (39.4) |

| Previous live births | 53 (26.8) |

| Hormonal therapy | |

| None | 109 (55.1) |

| Sequential oral contraceptive | 44 (22.2) |

| Norethisterone acetate | 20 (10.1) |

| Continuous oral contraceptive | 13 (6.6) |

| Norethisterone acetate and letrozole | 12 (6.1) |

Values were expressed as n (%) or mean±SD.

BMI, body mass index.

Table 2.

Intensity of pain and gastrointestinal symptoms of the study population (n=198)

| Patients with symptom, n (%) | Intensity (mean±SD) | |

| Dysmenorrhoea | 171 (86.4) | 6.9±1.6 |

| Deep dyspareunia | 127 (64.1) | 5.5±1.5 |

| Non-menstrual pelvic pain | 145 (73.2) | 5.7±1.2 |

| Dyschezia | 93 (47.0) | 5.1±1.9 |

| Diarrhoea-predominant IBS | 63 (31.8) | 7.1±2.1 |

| Constipation-predominant IBS | 87 (43.9) | 7.6±1.9 |

| Passage of mucus | 42 (21.2) | 6.1±1.7 |

| Rectal bleeding | 19 (9.6) | 5.3±1.1 |

| Intestinal cramping | 98 (49.5) | 6.8±1.9 |

| Abdominal bloating | 119 (60.1) | 6.5±2.2 |

Values were expressed as n (%) or mean±SD. Intensity of pain symptoms was assessed using 10 cm visual analogue scale.

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

Surgery together with histology verified that bowel endometriosis nodules existed in 110 patients (55.6%). Endometriosis lesions infiltrated intestinal serosa among 28 patients. The remaining 82 patients carried pelvic endometriosis, yet there was no evidence for intestinal lesions. The largest nodules of intestinal endometriosis were found located on anterior sigmoid of 53 patients, on upper anterior rectum of 30 patients, at rectosigmoid junction of 20 patients, on ileum of 5 patients and on caecum of 2 patients. Multifocal disease was found in 17 patients who had two nodules affecting the bowel. Fifteen cases were found to have those endometriosis lesions that only infiltrate intestinal serosa on anterior sigmoid, five cases were on rectum and three cases were at rectosigmoid junction. The mean(±SD) lengths of bowel segments that were resected were 12.2±3.6 cm. The endometriosis diagnosis was verified in all excised nodules by histology. Moreover, it showed that 62 patients (56.4%) had deepest endometriosis nodules infiltrating the muscularis propria, 31 patients (28.2%) with the submucosa infiltrated and 17 patients (15.5%) with the mucosa infiltrated.

Accuracy of DCBE and RWC-TVS in the bowel endometriosis diagnosis

Table 3 described the accuracy, specificity, sensitivity, NPV, PPV, LR– and LR+ of RWC-TVS and DCBE in the bowel endometriosis diagnosis. DCBE identified 106 among 110 patients of bowel endometriosis (96.4%). Four patients with the rectum muscularis propria infiltrated by endometriosis nodules were not defined, and the rectum muscularis propria were removed using partial-thickness nodulectomy. RWC-TVS identified 97 among 110 patients of intestinal endometriosis (88.2%). RWC-TVS was not able to identify three rectal nodules, four ileal lesions, two caecal lesions and four sigmoid nodules infiltrating muscularis propria. Moreover, we found four of the patients with large and bilateral endometriosis in ovarian cysts, and they may hamper the intestinal nodules identification. There were two false positives of RWC-TVS, where endometriosis nodules in rectovagina were defined to infiltrate rectum muscularis.

Table 3.

Diagnostic performance of RWC-TVS and DCBE in the diagnosis of bowel and rectosigmoid endometriosis (n=198)

| DCBE | RWC-TVS | |

| Bowel endometriosis | ||

| Sensitivity | 106/110 (96.4) | 97/110 (88.2) |

| Specificity | 97/97 (100) | 95/97 (97.3) |

| PPV | 106/106 (100) | 97/99 (98.0) |

| NPV | 97/101 (96.0) | 95/108 (88.0) |

| LR+ | N/A | 41.67 |

| LR– | 0.04 | 0.13 |

| Accuracy | 194/198 (98.0) | 183/198 (92.4) |

Values were expressed as n (%). Bowel endometriosis defined as disease infiltrating at least the muscularis propria. LR+ could not be calculated because there was no false positive. McNemar’s test with Yates continuity correction was used to compare the accuracy of DCBE and RWC-TVC.

DCBE, double-contrast barium enema; LR+, positive likelihood ratio; LR–, negative likelihood ratio; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; RWC-TVS, rectal water contrast transvaginal ultrasonography.

Surgery verified the rectovaginal nodule presence but did not reveal rectal muscularis infiltration. The specificity, sensitivity, NPV, PPV, LR–, LR+ as well as accuracy of these two techniques in the intestinal endometriosis diagnosis are presented in table 3. McNemar’s test displayed that no significant differences were found in accuracy of these two techniques for bowel endometriosis diagnosis (p=0.109). Histology examination showed that in 53 patients, endometriosis infiltrated rectosigmoid colon submucosa or mucosa. DCBE correctly defined the infiltration depth in 27 of the patients (50.9%), while RWC-TVS correctly defined the infiltration depth in 20 of the patients (37.7%) (p=0.126). All other nodules infiltrated the mucosa or submucosa by histology was identified to only reach muscularis at RWC-TVS and DCBE. Both of these two techniques did not have false-positive cases of submucosal or mucosal infiltration diagnosis. Both RWC-TVS and DCBE underestimated the endometriosis nodules size. Nevertheless, underestimation was smaller for DCBE than for RWC-TVS (table 4). Additionally, in both techniques, underestimation was larger for the nodules with the diameter ≥30 mm.

Table 4.

Difference between size of the largest nodule estimated by imaging techniques and that measured on histopathology

| Largest diameter on histology (mm, mean±SD) | DCBE mean difference (mm, 95% CI)* | DCBE limits of agreement (mm)† | RWC-TVS mean difference (mm, 95% CI)* | RWC-TVS limits of agreement (mm)† | |

| All nodules (n=110) | 28.5±6.9 | 1.62 (0.98 to 2.23) | −4.32 to 7.43 | 2.27 (1.23 to 3.43) | −3.12 to 4.23 |

| Nodules with diameter<30 mm (n=77) | 22.7±4.1 | 0.73 (0.11 to 1.32) | −2.92 to 5.37 | 1.65 (0.81 to 2.76) | −2.32 to 3.78 |

| Nodules with diameter≥30 mm (n=33) | 35.9±4.2 | 3.01 (1.96 to 4.15) | −5.56 to 8.34 | 3.91 (2.34 to 5.95) | −5.12 to 8.91 |

*Mean difference calculated by subtracting size of size of nodule by imaging technique from size of nodule measured on histology.

†Limits of agreement calculated as mean difference ±2 SDs of the difference.

DCBE, double-contrast barium enema; RWC-TVS, rectal water contrast transvaginal ultrasonography.

Tolerability of RWC-TVS and DCBE

DCBE was conducted safely in all patients. During both examinations, all patients were able to tolerate intestinal distension; therefore, no procedure interruption occurred. However, the pain intensity experienced in the course of DCBE was higher than that was experienced in the course of RWC-TVS (table 5). A positive correlation was detected between the pain intensity experienced by patients throughout these two examinations (Spearman’s correlation coefficient=0.575, p<0.001).

Table 5.

Intensity of pain experienced by 198 patients during RWC-TVS and DCBE as assessed on a 10 cm VAS

| Intensity of pain | RWC-TVS | DCBE | p value |

| Overall intensity of pain (mean±SD) | 3.9±1.8 | 4.9±2.3 | <0.001 |

| Categorical intensity of pain (n (%)) | <0.001 | ||

| Mild pain (VAS score<2) | 30 (15.2) | 9 (4.5) | |

| Moderate pain (VAS score≥2 and≤5) | 119 (60.1) | 80 (40.4) | |

| Severe pain (VAS score>5) | 49 (24.7) | 109 (55.1) |

The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the intensity of pain. The χ2 test was used to compare the type of pain.

DCBE, double-contrast barium enema; RWC-TVS, rectal water contrast transvaginal ultrasonography; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Discussion

This study is the first one to demonstrate that RWC-TVS and DCBE have comparable accuracy in bowel endometriosis diagnosis. Both DCBE and RWC-TVS underestimated the nodule size of bowel endometriosis, while underestimation was less for DCBE than for RWC-TVS, especially for the nodules with largest diameters≥30 mm as shown in table 4. Choosing ultrasonic technique often depends on the ultrasonographer experience rather than superiority evidence of one technique in comparison with others. In fact, TVS is required to be conducted by highly skilful professionals, and it was estimated recently that it requires conduction of about 40 cases17 for the learning curve of an accurate deep pelvic endometriosis diagnosis by TVS. Consequently, it is kind of difficult to attain such extent of experience for the ultrasonographers in small hospitals. Main advantage for DCBE is that, with the entire colon retrograde distension, it provides the complete overview for the entire colon.18 The aim in the current study was to compare with RWC-TVS and also right colon endometriosis lesions are outside of the transvaginal approach field view. The reason that RWC-TVS was selected to compare with DCBE was because of the personal experience and the common bowel distension criterion with fluid. The authors subsequently confirmed usefulness of this technique in large series. Additionally, other authors have confirmed that opacification and intestinal distension with ultrasound gel are helpful for visualising nodules of rectosigmoid endometriosis.19 20

Previous studies suggested the reliability of TVS for rectosigmoid endometriosis diagnosis. The TVS sensitivity for rectosigmoid endometriosis detection is from 91% to 98%, the specificity is from 97% to 100%, the PPV is from 97% to 100% and the NPV is from 87% to 98%.21–24 Recently, RWC-TVS was developed in order to facilitate intestinal lesion identification in patients of rectovaginal endometriosis as well as to determine endometriosis infiltration depth in intestinal wall.25 TVS was used in patients of bowel endometriosis extensively recently, though little results are available for DCBE use of these patients. This study verified that RWC-TVS and DCBE have comparable accuracy in bowel endometriosis diagnosis. Both of these two techniques estimated the rectosigmoid nodule length precisely, while DCBE was even accurate than RWC-TVS for measuring the distance from the anal verge to the endometriosis nodule.9 Visibly, the extensive experiences of the gynaecologist and the radiologist in RWC-TVS and DCBE may have affected the accurateness of the techniques in bowel endometriosis diagnosis.24 26 The findings could be explained by that when conducting imaging techniques, especially RWC-TVS, it may be difficult to choose the plane where the irregular nodule of endometriosis has the longest diameter. Nevertheless, difference between the longest diameter and the estimated nodule size as assessed by histopathology was very small and also, most of the times it does not seem that this difference influences the choice for bowel resection or nodulectomy as treatment.27 Importantly, the patients tolerated RWC-TVS better than they did with DCBE. The findings are consistent with those previous studies indicating the accurateness of TVS for bowel endometriosis diagnosis and its comparison of TVS with the other techniques like rectal endoscopic ultrasound and MRI.11 28–30

Researchers have questioned potential benefits by the introduction of aqueous contrast medium into rectum through TVS. TVS is dependent on the operator and it is possible that differences observed for the accurateness by the technique are caused by the ultrasonographer experience conducting the procedure.31 However, application of intestinal aqueous in contrast to TVS could facilitate the rectosigmoid lesion identification. Other methods have been suggested for improving the TVS accuracy in deep endometriosis detection, including using large amount transmission gel for ultrasound (12 mL) in probe cover or sonovaginography.32 Till now, there is no study that has demonstrated any ultrasonic technique better than others in deep endometriosis diagnosis.

TVS was suggested to be considered as the first investigation for patients of deep endometriosis and TVS allows for intestinal lesions diagnosis.24 Other investigations including DCBE, MDCT-e, RWC-TVS, rectal endoscopic ultrasound and MRI should be used to determine intestinal endometriosis characteristics, such as the nodules size and number, the intestinal wall infiltration depth of nodules and the stenosis degree of bowel lumen.33–35 RWC-TVS has some advantages over other techniques. For example, RWC-TVS is less expensive than MRI and MDCT-e, and the required equipment for RWC-TVS is usually available to the gynaecologists, who are typically involved in the management of patients with endometriosis. Recently, a study showed that RWC-TVS permits the stenosis degree estimation of intestinal lumen which is caused by the endometriosis.36 Unfortunately, the current study did not examine this parameter, which is a limitation in our investigation. Theoretically, RWC-TVS should also permit determination of the disease extent along longitudinal axis of the intestine. Apparently, RWC-TVS could not determine intestinal nodule presence located in the proximal of sigmoid because the lesions are outside of the view field in TVS.

The current study has several limitations. First, experience of ultrasonographer conducting RWC-TVS may affect the accuracy of the techniques in bowel endometriosis diagnosis. Second, the surgeons know the findings by RWC-TVS and DCBE. In an ideal study, surgeons should be blind to the findings of preoperative investigations, but this theoretical design is unethical clinically, for diagnostic imaging would facilitate the nodule identification of intestinal endometriosis during surgery. Moreover, the knowledge of the preoperative investigation findings only helps the surgeons to identify actually presenting endometriosis nodules. Third, DCBE and RWC-TVS did not estimate the circumference percentage of intestinal wall that was infiltrated by the endometriosis, a criterion for choosing between bowel resection and nodulectomy. Hence, patients scheduling for nodulectomy based on the findings of RWC-TVS and DCBE should be aware of that the bowel resection may be required to excise the intestinal endometriosis completely. At last, the study was also limited in that we didn’t assess the accuracy of the two techniques in estimating the distance between the lower margin of the lesion and the anal verge, which should be addressed in our follow-up study. Future studies would also investigate whether RWC-TVS and DCBE can estimate the intestinal circumference percentage by endometriosis infiltration reliably. DCBE might still play a role for diagnosis workup in patients of suspicious bowel endometriosis. When RWC-TVS or TVS shows bowel muscular is infiltrated by big intestinal nodules, the bowel resection could probably be conducted without further examinations unless surgeons want to exclude the intestinal lesions close to sigmoid. When ultrasound shows one bowel nodule which might be removed by using nodulectomy, DCBE is better to be used to exclude other intestinal nodule presence in order to plan the operating procedure with colorectal surgeon as well as the patient adequately.

This study demonstrated RWC-TVS as a very reliable technique to determine the bowel endometriosis presence and extent and it has similar accuracy to that of DCBE. Nevertheless, RWC-TVS may underestimate multiple bowel nodule presence sometimes and be conducted easily in the ambulatory setting; also, it is easily tolerated by the patients. It is hypothesised to combine DCBE and TVS to attain a complete bowel preoperative assessment so as to provide adequate counselling to the patients and the most suitable surgical treatment in one step.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JJ, YL, KW and XW collected the data. YT designed the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the final submission.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Institutional review board of Tianjin First Center Hospital approved the protocols involved in this study before initialisation of the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. No additional unpublished data.

References

- 1. Remorgida V, Ferrero S, Fulcheri E, et al. Bowel endometriosis: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2007;62:461–70. 10.1097/01.ogx.0000268688.55653.5c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Remorgida V, Ragni N, Ferrero S, et al. The involvement of the interstitial cajal cells and the enteric nervous system in bowel endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2005;20:264–71. 10.1093/humrep/deh568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ferrero S, Biscaldi E, Morotti M, et al. Multidetector computerized tomography enteroclysis vs. rectal water contrast transvaginal ultrasonography in determining the presence and extent of bowel endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011;37:603–13. 10.1002/uog.8971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Menada MV, Remorgida V, Abbamonte LH, et al. Transvaginal ultrasonography combined with water-contrast in the rectum in the diagnosis of rectovaginal endometriosis infiltrating the bowel. Fertil Steril 2008;89:699–700. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.07.1336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Abrao MS, Gonçalves MO, Dias JA, et al. Comparison between clinical examination, transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of deep endometriosis. Hum Reprod 2007;22:3092–7. 10.1093/humrep/dem187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Podgaec S, Abrao MS, Dias JA, et al. Endometriosis: an inflammatory disease with a Th2 immune response component. Hum Reprod 2007;22:1373–9. 10.1093/humrep/del516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leone Roberti MU, Biscaldi E, Vellone GV, et al. Magnetic resonance enema versus rectal water contrast transvaginal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016. doi: 10.1002/uog.15934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ferrero S. Endometriosis: modern management of an ancient disease. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2017;209:1–2. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.12.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ferrero S, Biscaldi E, Vellone VG, et al. Computed tomographic colonography versus rectal-water contrast transvaginal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis: a pilot study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guerriero S, Condous G, van den Bosch T, et al. Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: a consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis analysis (IDEA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016;48:318–32. 10.1002/uog.15955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hudelist G, English J, Thomas AE, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for non-invasive diagnosis of bowel endometriosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011;37:257–63. 10.1002/uog.8858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leone Roberti Maggiore U, Ferrero S, Mangili G, et al. A systematic review on endometriosis during pregnancy: diagnosis, misdiagnosis, complications and outcomes. Hum Reprod Update 2016;22:70–103. 10.1093/humupd/dmv045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Savelli L, Manuzzi L, Coe M, et al. Comparison of transvaginal sonography and double-contrast barium enema for diagnosing deep infiltrating endometriosis of the posterior compartment. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011;38:466–71. 10.1002/uog.9072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Darwish B, Roman H. Surgical treatment of deep infiltrating rectal endometriosis: in favor of less aggressive surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;215:195–200. 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.01.189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Darwish B, Roman H. Nerve sparing and surgery for deep infiltrating endometriosis: pessimism of the intellect or optimism of the will. Semin Reprod Med 2017;35:072–80. 10.1055/s-0036-1597305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roman H, Darwish B, Schmied R, et al. Combined vaginal-laparoscopic-transanal approach for reducing bladder dysfunction after conservative surgery in large deep rectovaginal endometriosis. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod 2016;45:546–8. 10.1016/j.jgyn.2015.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tammaa A, Fritzer N, Strunk G, et al. Learning curve for the detection of pouch of Douglas obliteration and deep infiltrating endometriosis of the rectum. Hum Reprod 2014;29:1199–204. 10.1093/humrep/deu078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Scardapane A, Bettocchi S, Lorusso F, et al. Diagnosis of colorectal endometriosis: contribution of contrast enhanced MR-colonography. Eur Radiol 2011;21:1553–63. 10.1007/s00330-011-2079-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Loubeyre P, Copercini M, Frossard JL, et al. Pictorial review: rectosigmoid endometriosis on MRI with gel opacification after rectosigmoid colon cleansing. Clin Imaging 2012;36:295–300. 10.1016/j.clinimag.2011.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Loubeyre P, Petignat P, Jacob S, et al. Anatomic distribution of posterior deeply infiltrating endometriosis on MRI after vaginal and rectal gel opacification. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009;192:1625–31. 10.2214/AJR.08.1856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bazot M, Lafont C, Rouzier R, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination, transvaginal sonography, rectal endoscopic sonography, and magnetic resonance imaging to diagnose deep infiltrating endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2009;92:1825–33. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Goncalves MO, Podgaec S, Dias JA, et al. Transvaginal ultrasonography with bowel preparation is able to predict the number of lesions and rectosigmoid layers affected in cases of deep endometriosis, defining surgical strategy. Hum Reprod 2010;25:665–71. 10.1093/humrep/dep433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bazot M, Malzy P, Cortez A, et al. Accuracy of transvaginal sonography and rectal endoscopic sonography in the diagnosis of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007;30:994–1001. 10.1002/uog.4070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Piketty M, Chopin N, Dousset B, et al. Preoperative work-up for patients with deeply infiltrating endometriosis: transvaginal ultrasonography must definitely be the first-line imaging examination. Hum Reprod 2009;24:602–7. 10.1093/humrep/den405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Valenzano Menada M, Remorgida V, Abbamonte LH, et al. Does transvaginal ultrasonography combined with water-contrast in the rectum aid in the diagnosis of rectovaginal endometriosis infiltrating the bowel? Hum Reprod 2008;23:1069–75. 10.1093/humrep/den057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ferrero S, Anserini P, Abbamonte LH, et al. Fertility after bowel resection for endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2009;92:41–6. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.04.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fritzer N, Tammaa A, Salzer H, et al. Dyspareunia and quality of sex life after surgical excision of endometriosis: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2014;173:1–6. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.10.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Minguez JA, et al. Accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for diagnosis of deep endometriosis in uterosacral ligaments, rectovaginal septum, vagina and bladder: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;46:534–45. 10.1002/uog.15667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Orozco R, et al. Accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for diagnosis of deep endometriosis in the rectosigmoid: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016;47:281–9. 10.1002/uog.15662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hudelist G, Ballard K, English J, et al. Transvaginal sonography vs. clinical examination in the preoperative diagnosis of deep infiltrating endometriosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011;37:480–7. 10.1002/uog.8935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Biscaldi E, Ferrero S, Remorgida V, et al. Rectosigmoid endometriosis with unusual presentation at magnetic resonance imaging. Fertil Steril 2009;91:278–80. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Gerada M, et al. 'Tenderness-guided' transvaginal ultrasonography: a new method for the detection of deep endometriosis in patients with chronic pelvic pain. Fertil Steril 2007;88:1293–7. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.12.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Philip CA, Bisch C, Coulon A, et al. Correlation between three-dimensional rectosonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis: a preliminary study on the first fifty cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2015;187:35–40. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Landi S, Barbieri F, Fiaccavento A, et al. Preoperative double-contrast barium enema in patients with suspected intestinal endometriosis. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc 2004;11:223–8. 10.1016/S1074-3804(05)60203-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Biscaldi E, Ferrero S, Leone Roberti Maggiore U, et al. Multidetector computerized tomography enema versus magnetic resonance enema in the diagnosis of rectosigmoid endometriosis. Eur J Radiol 2014;83:261–7. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bergamini V, Ghezzi F, Scarperi S, et al. Preoperative assessment of intestinal endometriosis: a comparison of transvaginal sonography with water-contrast in the rectum, transrectal sonography, and barium enema. Abdom Imaging 2010;35:732–6. 10.1007/s00261-010-9610-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.