Abstract

Objectives

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) can be effectively treated with internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy (ICBT), but studies on long-term cost minimisation from a healthcare provider perspective in comparison to an evidence-based control treatment of therapeutic equivalence are lacking. The objective of the study was to determine whether ICBT reduces healthcare costs and use of healthcare resources compared with cognitive behavioural group therapy (CBGT).

Design

A cost-minimisation study alongside a randomised controlled trial where participants (n=126) with SAD were randomised to ICBT or to CBGT. Costs measured from a healthcare provider perspective were estimated using time-driven activity-based costing alongside health status over 4 years from baseline measured with EQ-5D.

Setting

A psychiatric outpatient clinic in Stockholm, Sweden.

Participants

Participants were 126 individuals with SAD.

Primary outcome measures

Changes in EQ-5D and costs.

Interventions

Participants received either CBGT or ICBT for a duration of 15 weeks.

Results

ICBT minimised healthcare costs and demonstrated health improvements within the non-inferiority margin. Assuming a practical work capacity for personnel varying between 100%, 80% and 50% of theoretical full capacity, the cost for ICBT varied in the range between 400€, 463€ and 654 €, while the cost for CBGT varied between 699€, 806€ and 1134€. Within-group effect size was −0.36 (95% CI −0.70 to −0.01) for ICBT and −0.25 (95% CI −0.60 to 0.10) for CBGT. Mean use of effective psychologist time in ICBT was 189.60 (SD=53.77) minutes compared with 499.78 (SD=30.91) in the CBGT group.

Conclusions

In treatment of SAD, ICBT is equally effective but is associated with more efficient staff utilisation and less costs compared with CBGT. From a healthcare provider perspective, ICBT is an advantageous treatment option.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Psychiatry, Anxiety Disorders, Public Health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Randomised controlled design.

Low attrition rates.

Includes long-term follow-up data.

It may be difficult to generalise time and cost estimates of resource use to other settings.

Introduction

Common mental health problems including depression and anxiety disorders are a major concern globally, and in the UK affecting approximately 17% of the population.1 The cost of these problems in England alone has been estimated at £105.2 billion (approximately 121 billion Euros) which includes costs associated with reduced health-related quality of life, lost productivity and social and healthcare costs.2 Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is one of the most prevalent anxiety disorders with a 12-month prevalence of 2.8%–7.1% and a lifetime prevalence of 5%–12.1%.3–5 SAD is associated with functional impairment and typically follows a chronic course if untreated.6–9 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK recommends cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) as the first-line treatment option for SAD.10 Cognitive behavioural group therapy (CBGT) is an effective format of CBT provision in the treatment of SAD.11 12 Although many patients prefer psychological therapies to medication, access is limited in both primary and secondary care.13

Recently, internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (ICBT) has emerged as an empirically supported treatment for SAD with effect sizes on par with those of CBGT and tested in at least 16 randomised controlled trials (RCTs).14 Our research group has previously compared ICBT to CBGT in a non-inferiority trial and found ICBT to be at least as effective as CBGT.15 At post-treatment, it was observed that 55% (95% CI 42.5% to 66.9%) of patients having received ICBT were classified as responders, compared with 34% (95% CI 22.1% to 45.7%) having received CBGT. At 6-month follow-up, the corresponding numbers were 64% (95% CI 52.3% to 75.8%) in the ICBT group and 45% (95% CI 32.8% to 57.6%) in the CBGT group.

Even though some previous studies indicate that ICBT for SAD can be cost-effective,16 17 evidence is lacking concerning health economic evaluations from a healthcare provider perspective. In the present study, we used the time-driven activity-based costing (TDABC) method, which takes into account all costs related to the treatment from the healthcare provider’s perspective. To our knowledge, this has not been previously done when evaluating ICBT for SAD.

In health economic evaluations, a choice is often made between four types of methods: a cost–benefit analysis (CBA) in which both benefits and costs are expressed in monetary terms; a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) where costs and treatment effects are compared; a cost-utility analysis which is similar to CBA and CEA but where benefits is expressed in terms of quality-adjusted life years; and finally, cost-minimisation analysis (CMA), which focuses on comparing the costs of different treatments with previously demonstrated equivalence in clinical efficacy.

Given the equivalence of both treatment formats in terms of health improvements previously demonstrated in a RCT,15 the purpose of this study was to assess whether ICBT may help minimise the costs of healthcare use relative to CBGT. This was done by using both data from a RCT and additionally collected data on resource use. In contrast to previous health economic evaluations,16 18 the present study adopted a healthcare provider perspective using TDABC methodology. If ICBT is found to help minimise the costs of healthcare use relative to CBGT, such internet-based interventions have the potential to increase access to psychological therapy in psychiatry and primary care and could represent an efficient alternative psychological treatment for SAD.

Method

Design

This was a CMA adopting a healthcare provider perspective, conducted alongside a non-inferiority trial within the context of a parallel group study with unrestricted randomisation in 1:1 ratio (ICBT or CBGT). Costs measured from a healthcare provider perspective were estimated using TDABC alongside with health status over 4 years from baseline measured with EQ-5D. All costs were estimated based on thorough assessment of the costs associated with ICBT when delivered in regular care (which was implemented at the clinic after the RCT); this was done in order not to underestimate the treatment costs. The trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT00564967). The main outcome study has been reported elsewhere.15

Recruitment, inclusion criteria and participants

The study was conducted at a public ICBT unit in Stockholm, Sweden (Stockholm Healthcare Services). Participants were recruited by self-referral (n=97) or by referral from primary care physicians and psychiatrists (n=29). The study protocol was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The recruitment took place between 2007 and 2009. The participant flow throughout the trial is presented in the main outcome study.15

Treatments

Internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy

The internet-delivered treatment was based on and adapted from a treatment originally developed by Andersson and colleagues and followed a CBT model developed for individual therapy of SAD.19–21 The treatment content was accessed as text modules similar to chapters in self-help bibliotherapy. Each chapter corresponded to a CBT session with a specific theme such as cognitive restructuring, graded exposure or behavioural experiments, coupled with homework assignments. Patients received supportive email feedback from a psychologist after each module. The duration of the internet-based intervention was 15 weeks, and therapists were instructed to restrict time spent on each patient to approximately 10 min per week.

Cognitive behavioural group therapy

The group CBT for SAD followed the protocol developed by Heimberg and Becker22 . The treatment was equally long as the ICBT (ie, 15 weeks) consisting of one initial individual session followed by 14 group sessions. Each session was 2.5 hours long and led by therapists trained in CBT. Each group consisted of six to seven patients.

Outcome measure

EuroQol (EQ-5D) index values were used to assess improvements in health-related quality of life . The EQ-5D is non-disease specific and measures five health domains of importance to quality of life: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression.

Resource use

Resource use was estimated by using a bottom-up approach where clinical and administrative activities performed throughout the treatment delivery cycle were first documented through process maps. This allowed us to identify resource use in terms of type (eg, personnel, hospital space, information technology (IT)) and time (measured in minutes and collected through time studies and interviews). The time studies and estimations on resource use were conducted at the treatment facility after the original RCT had been completed, that is, when the treatment had been implemented as routine care.

Costs

TDABC was used to determine the costs associated with ICBT and CBGT from a healthcare provider perspective.24 Based on estimated resource use, the capacity cost rate (ie, cost per minute) was calculated for each resource. The overall approach for calculating capacity cost rates involved the allocating of costs such as hospital space, IT usage (including hardware and software), security and safety, management and clinical supervision evenly per minute. Costs for hospital space were calculated as the price per square metre divided by floor space usage per staff category. Shared costs included management as well as shared unit administration. The minute cost for each personnel category therefore include these allocated costs. Economic data for these costs were provided from the general ledger for the psychiatric department. However, costs related to prior training of staff and the actual software development of the ICBT platform were not included; rather, the day-to-day costs of administering treatment were the focus of this study.

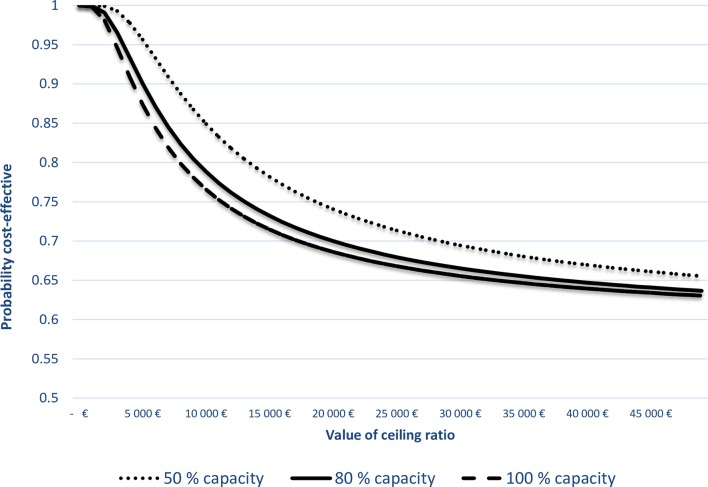

The minute cost for each staff category was calculated by dividing the total annual salary by the total number of minutes worked. Since not all time worked were available for clinical care due to meetings, training and breaks etc., the practical capacity was estimated to be 80% of the actual number of worked hours, which is typically used as a standard assumption.24 A sensitivity analysis have been performed to study the effects of changing this rate down to 50% or up to 100%, presented in a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) to summarise the uncertainty of the estimates in the CEA.

Finally, the total cost of each treatment episode was calculated for each patient by multiplying the estimated minute cost for each resource with the assumed average number of minutes spent on each activity and then summing across all resources. In addition to calculating actual costs, costs were also estimated when discounted at annual rates of 3% and 5%, respectively, and presented in Euros, year 2017 values.

Cost-minimisation analysis

Since the main outcome study demonstrated equivalence in treatment efficacy, we chose to conduct a CMA where costs per course of treatment from a healthcare provider perspective were calculated and compared between treatment groups; if total costs are reduced by more efficient resource use, cost minimisation may be achieved.25 In order to avoid biased estimation of uncertainty, we have used the statistical methods of cost-effectiveness to evaluate the joint distributions of costs and benefits.

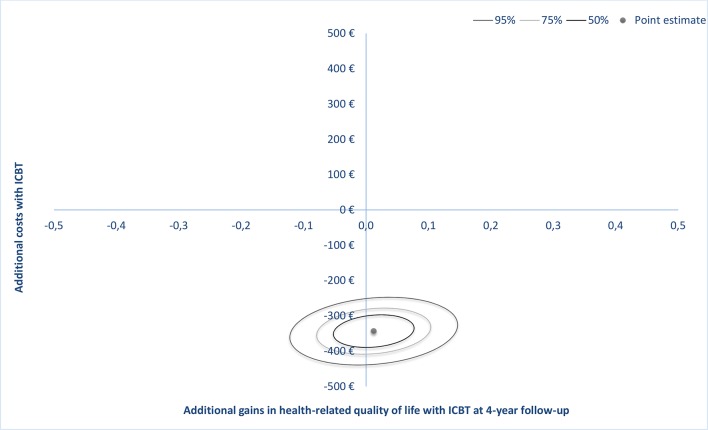

The CEA was conducted through the following steps: (a) calculation of costs and effects of each intervention, (b) calculation of the differences in cost and differences in effects and (c) calculating the incremental cost and incremental benefit of ICBT versus CBGT and (d) presenting the distribution of cost/effect differences on a cost-effectiveness plane with CI estimation around the calculated ratio.26 If ICBT is found to be equally effective but less costly, it will be located in the south quadrants on the cost-effectiveness plane close to the y-axis. If the effectiveness of the interventions differs between the two study groups, the question then arises whether the cost savings of ICBT is worth the health loss or health gain relative to CBGT.

Sensitivity analysis

A probability sensitivity analysis was performed to estimate the uncertainty surrounding the cost-effectiveness ratios. Confidence ellipses at 50%, 75% and 95% were calculated and CEACs were constructed to represent the uncertainty around the estimate27 in accordance with recommended guidelines.28 Incremental net benefit (INB) was used to interpret the CEAC, where the slope of the net monetary benefits (NMB) curve represents the difference in effects between ICBT and CBGT.

Results

Outcomes

As previously reported,18 the between-group effect size on EQ-5D was −0.18 (95% CI −0.53 to 0.17), indicating equivalence in treatment effects. The within-group effect size was −0.36 (95% CI −0.70 to −0.01) for ICBT and −0.25 (95% CI −0.60 to 0.10) for CBGT. Treatment adherence was similar across treatment conditions; out of possible 15 sessions/modules, mean number of attended sessions was 9.40 (SD=4.87) in the CBGT group and 9.33 (SD=4.95) accessed modules in the ICBT group. As previously reported, number of treatment sessions/modules was positively related to treatment outcome.29

Resource use

An independent-samples t-test was conducted to compare psychologist time in ICBT and CBGT treatments. There was a significantly lower use of psychologist time in ICBT (M=189.60, SD=53.77) compared with CBGT (M=499.78, SD=30.91), with a mean difference of 310.16 (95% CI 248.47 to 371.86) min; t(124) = 9.95, p<0.001. Table 1 presents average number of minutes consumed per resource category over a complete cycle of care.

Table 1.

Estimation of a patient's cost over a complete cycle of care for treating social anxiety disorder with internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (ICBT) or with cognitive behavioural group therapy (CBGT)

| Coordinating nurse | Psychiatrist | Resident physician | Psychologist | Medical secretary | Total | |||||||

| Average minutes | Average cost | Average minutes | Average cost | Average minutes | Average cost | Average minutes | Average cost | Average minutes | Average cost | Average minutes | Average cost | |

| ICBT | ||||||||||||

| Registration and verification | 11 | 13€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 11 | 13€ |

| Diagnostic assessment | 0 | 0€ | 20 | 43€ | 80 | 112€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 100 | 154€ |

| Supervision meeting/discussion | 0 | 0€ | 3 | 6€ | 3 | 4€ | 1 | 1€ | 0 | 0€ | 7 | 11€ |

| Supplementary psychological assessment | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 5 | 7€ | 0 | 0€ | 5 | 7€ |

| Administrating treatment activation | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 41 | 41€ | 41 | 41€ |

| ICBT intervention (online) | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 82 | 102€ | 0 | 0€ | 82 | 102€ |

| ICBT intervention (offline) | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 77 | 95€ | 0 | 0€ | 77 | 95€ |

| Administrative preparation for follow-up visit | 3 | 3€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 3 | 3€ |

| Post-treatment clinical visit | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 24 | 30€ | 0 | 0€ | 24 | 30€ |

| Discharge | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 5 | 5€ | 5 | 5€ |

| Total | 14 | 17€ | 23 | 49€ | 83 | 116€ | 190 | 235€ | 46 | 46€ | 355 | 463€ |

| CBGT | ||||||||||||

| Registration and verification | 11 | 13€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 11 | 13€ |

| Diagnostic assessment | 0 | 0€ | 20 | 43€ | 80 | 112€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 100 | 154€ |

| Supervision meeting/discussion | 0 | 0€ | 3 | 6€ | 3 | 4€ | 1 | 1€ | 0 | 0€ | 7 | 11€ |

| Supplementary psychological assessment | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 5 | 7€ | 0 | 0€ | 5 | 7€ |

| CBGT intervention | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 470 | 582€ | 0 | 0€ | 470 | 582€ |

| Administrative preparation for follow-up visit | 3 | 3€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 3 | 3€ |

| Post-treatment clinical visit | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 24 | 30€ | 0 | 0€ | 24 | 30€ |

| Discharge | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 0 | 0€ | 5 | 5€ | 5 | 5€ |

| Total | 14 | 17€ | 23 | 49€ | 83 | 116€ | 500 | 619€ | 5 | 5€ | 625 | 806€ |

Costs and cost minimisation

Assuming a practical capacity of 80% of full theoretical capacity for healthcare staff, mean total healthcare costs are reported in table 1. Taking into account the complete treatment episode, total estimated cost for ICBT was 463€ (95% CI 446€ to 480€) per patient compared with 806€ (95% CI 730€ to 883€) for CBGT. Table 1 also presents the average costs for each resource involved in the complete care episode, where costs of hospital space, supervision, IT and management have been allocated over each staff category.

Estimated capacity cost rates (cost per minute) for each staff category are presented in table 2 for different assumptions of practical capacity. Estimations indicate that the cost per minute increases as less time is spent on clinical work.

Table 2.

Cost rates (€/min) at different assumptions of practical capacity

| Practical capacity assumption | Medical secretaries | Psychiatrist | Resident physician | Psychologists | Coordinating nurse |

| 100% | 0.90 | 1.79 | 1.19 | 1.08 | 1.06 |

| 80% | 1.02 | 2.13 | 1.40 | 1.24 | 1.21 |

| 50% | 1.38 | 3.14 | 2.02 | 1.73 | 1.67 |

Estimated healthcare cost for different assumptions of practical capacity is presented in table 3. Assuming that staff spends 100% of their theoretical full capacity on clinical work directly related to the treatment processes, the total cost of CBGT is estimated at 699€ (95% CI 632€ to 765€) compared with 400€ (95% CI 386€ to 415€) for ICBT.

Table 3.

Estimated healthcare cost for different assumptions of practical capacity

| Assumed practical capacity | n | Cost (€) | 95% CI | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| CBGT | 50% | 62 | 1134 | 1027 | 1241 |

| 80% | 62 | 806 | 730 | 883 | |

| 100% | 62 | 699 | 632 | 765 | |

| ICBT | 50% | 64 | 654 | 630 | 677 |

| 80% | 64 | 463 | 446 | 480 | |

| 100% | 64 | 400 | 386 | 415 | |

CBGT, cognitive behaviouralgroup therapy; ICBT,internet-basedcognitive behavioural therapy.

The estimated cost savings of ICBT relative to CBGT at different assumptions of practical capacity is presented in table 4, ranging from 299€ (95% CI 232€ to 356€) to 481€ (95% CI 374€ to 587€). Assuming a practical capacity of 80%, the cost saving is estimated to be 343€ (95% CI 267€ to 420€).

Table 4.

Estimated mean differences in healthcare cost between ICBT and CBGT for different assumptions of practical capacity

| Assumed practical capacity of full theoretical capacity | Mean cost difference (€) | 95% CI of the difference | |

| Lower | Upper | ||

| 50% | 481 | 374 | 587 |

| 80% | 343 | 267 | 420 |

| 100% | 299 | 232 | 365 |

Independent-samples t-tests were conducted to compare total costs for ICBT and CBGT for different levels of assumed practical capacity in relation to theoretical full capacity, indicating significant differences in healthcare costs; t(124)=8.9, p<0.001.

CBGT, cognitive behavioural group therapy; ICBT, internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy.

figure 1 illustrates confidence ellipses around the point estimate; as the 95% and 75% confidence ellipses occupy both the southeast and southwest quadrants, this indicates that the ICBT treatment was equally effective but less costly relative to the CBGT intervention; the entire density within the ellipses involves cost savings. Table 5 presents costs and mean differences when taking account of time (at an assumption of 80% practical capacity), assuming 3% and 5% annual discount rates; when costs were discounted at 3%, the mean difference was 305€ (95% CI 237€ to 373€) and 283€ (95% CI 220€ to 345€) at a 5% discount rate.

Figure 1.

Mean differences in costs and gained health-related quality of life. Each confidence ellipse represents regions with a 50%, 75% or 95% certainty around the mean difference in cost and effect. ICBT, internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy.

Table 5.

Estimation of actual and discounted costs of care for treating social anxiety disorder with internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy (ICBT) or with cognitive behavioural group therapy (CBGT)

| Group | N | Mean cost, € | SD | Mean difference, € | 95% CI of the difference | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Total costs, actual | CBGT | 62 | 806 | 302 | |||

| ICBT | 64 | 463 | 67 | 343 | 267 | 420 | |

| Total costs, discounted at 3% per year | CBGT | 62 | 717 | 268 | |||

| ICBT | 64 | 411 | 59 | 305 | 237 | 373 | |

| Total costs, discounted at 5% per year | CBGT | 62 | 663 | 248 | |||

| ICBT | 64 | 381 | 55 | 283 | 220 | 345 | |

CEACs are presented in figure 2, including a sensitivity analysis of different assumptions of practical capacity applied in the calculation of cost rates. The CEACs indicate the probability that ICBT is cost-effective compared with CBGT for a given value of the maximum willingness to pay (WTP) for a gained unit of health-related quality of life. As can be seen, the probability for ICBT being cost-effective is high regardless of WTP.

Figure 2.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves for different assumptions of practical capacity. The cost-effectiveness acceptability curves show for different assumptions of personnel’s practical work capacity of their full theoretical capacity, the probabilities that internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy is cost-effective with changes in the amount that society is willing to pay for a unit increase in health-related quality of life, considering healthcare costs.

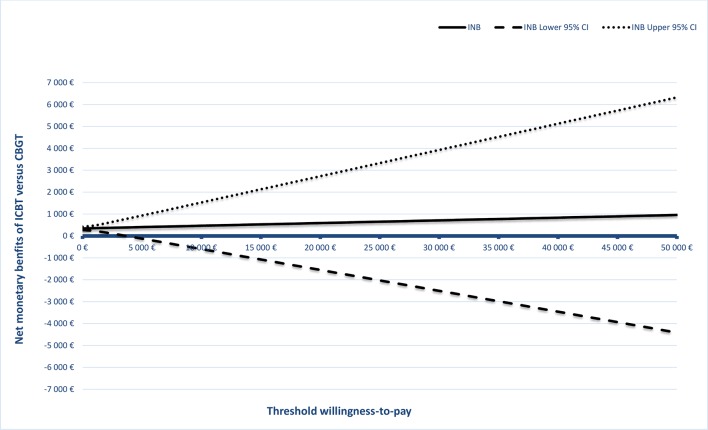

A graphical representation of the net benefit is illustrated in figure 3. The uncertainty of the value of the intervention gets larger as the WTP for the clinical outcome increases; this is reflected in the increasing CI of the INB. The positive NMBs suggest that the intervention is cost-effective at 4-year follow-up assessment.

Figure 3.

Net monetary benefit curves and 95% CIs at 4-year follow-up. CBGT, cognitive behavioural group therapy.

Discussion

Principal findings

The objective of this study was to assess whether ICBT is less costly relative to CBGT while equally effective in the treatment of patients with SAD. While clinical treatment effects were equivalent, healthcare costs were lower in the ICBT group (463€) compared with the CBGT group (806€), assuming a practical work capacity for personnel of 80% of theoretical full capacity. This finding indicates that ICBT for SAD is less costly compared with CBGT from a healthcare provider perspective. These results add to the previous body of research demonstrating that ICBT is associated with improved economic outcomes.30 However, most health economic evaluations have mainly been performed from a societal perspective. By using a healthcare provider perspective, and a TDABC costing approach, this study may help to develop a greater understanding of the costs incurred by the resources used throughout the clinical care of patients and by their administrative processes.

Implications for policy and practice

Evidence suggests that ICBT is equally effective as the more commonly provided face-to-face CBT, not only for SAD15 31 but for a wide range of mood and anxiety disorders,32 while requiring less healthcare resources. Therefore, ICBT may have a number of advantages that would benefit both healthcare providers and patients. First, since ICBT requires significantly less therapist time, each therapist is able to treat more patients simultaneously, consequentially increasing treatment availability and shortening waiting lists. Another advantage is that ICBT overcomes geographic barriers for patients and may therefore provide access to evidence-based psychological treatment more equally. Finally, accessing therapy sessions online is practical and more economical for patients since it enables them to work with the treatment at their own convenience and not having to take time off work for making visits to their healthcare provider. To further increase access to evidence-based psychological interventions for SAD, ICBT may be considered as an alternative to face-to-face psychological therapies as an initial step within a stepped care approach. This should also be considered for other evidence-based ICBT applications such as in depression and panic disorder.

Strengths and limitations

Main strengths of the present study were the randomised controlled design, direct comparison of ICBT against face-to-face CBT and low attrition rates.

The use of TDABC as a costing methodology in healthcare is howevere relatively new, particularly within mental healthcare; it has been more commonly used in industry.33–35 Therefore, its validity may be difficult to evaluate at this stage and may therefore represent a limitation. Also, although CBT treatment delivery may be similar across different healthcare providers, supporting administrative processes and clinical practices might differ significantly. As a result, it may be difficult to generalise time and cost estimates of the total healthcare episode to other settings and healthcare providers.

Anotherlimitation relates to difficulties in arriving at accurate time estimates of resource use and activities performed. Since actual logging of time requires an electronic measurement system, only accurate timing of the amount of time each psychologist spent with each patient in ICBT could be recorded (thus allowing estimation of variability), whereas other clinical and administrative processes were based on estimated average standard times.

Third, parts of the time studies and estimations on resource use were carried out several years after the original RCT, that is, when the treatment had been implemented as routine care. Although administrative routines and processes have remained more or less similar over the years, there may still be minor differences when compared with how the administrative processes were during the RCT. Therefore, difficulties in retrieving exact cost data may add to the uncertainty around cost estimates.

Fourth, since our study is based on a non-inferiority trial with observed equivalence in treatment effects, the CI suggested some uncertainty around the estimated effect. This concern in CEAs has been discussed by Briggs and O’Brien36; in line with the recommendations outlined in the article, we have aimed at providing an appropriate representation of uncertainty using confidence ellipses on the cost-effectiveness plane.

Finally, we will comment on the use of CMA in the present study. Economic evaluations in healthcare compare treatment options or technologies in terms of clinical effects and costs, typically resulting in a cost-effectiveness ratio. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) summarises the cost-effectiveness of a treatment relative to an alternative by calculating the difference in costs between the two divided by the difference in effects.25 We have previously estimated an ICER from a societal perspective using the formula (CICBT–CCBGT)/(EICBT–ECBGT), where CICBT and EICBT represent the cost and effect in the ICBT group and CCBGT and ECBGT represent the cost and effect in the CBGT group.16 18 The difference between CEA and CMA has been further discussed elsewhere37; a full CEA is often a preferred method to assess differences in both costs and effects. However, in the context of a non-inferiority trial where treatments have been found to be equally effective, CMA may be an appropriate method to analyse cost differences,25 since the focus of interest is which treatment is less expensive. Since both treatments in this study were found to have equivalent efficacy, estimating an ICER may not be the optimal approach as the ICER approaches infinity when effect difference is close to zero. However, if ICBT can reduce resource use in treatment of SAD, it may lower healthcare costs. Therefore, a cost-minimisation approach was considered more appropriate in this case.

Conclusion

In treatment of SAD, ICBT is equally effective but is associated with more efficient staff utilisation and considerably lower costs compared with CBGT. From a healthcare provider perspective, ICBT is an advantageous treatment option.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs Ann Edholm-Johansson and the late Mr Stefan Lundkvist at Stockholm Healthcare Services, Psychiatry Division, for assembling and calculating some of the cost data.

Footnotes

Contributors: SEA designed the study, performed the analyses, collected and interpreted the data and drafted the paper. EH designed the study, developed the SAD treatment, performed the analyses and drafted the paper. NL and BLJ designed the study, interpreted the data and drafted the paper.

Funding: This research was founded by Karolinska Institutet and Stockholm County Council, none of which had any role in the design, execution or publication of the study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Study data are stored at the repository of Karolinska Institutet. With respect to the legal framework regulating access to research data in Sweden, the data are not freely accessible due to regulations regarding personal integrity in research, public access and privacy; each request is therefore assessed by the Karolinska Institutet ethics committee, and approval of data access can be given after this assessment. To request data, contact Karolinska Institutet by e-mail at info@ki.se, or at Karolinska Institutet, SE-171 77, Stockholm, Sweden.

References

- 1. Bebbington P, Brugha T, Coid J, et al. Adult Psychiatric Morbidity in England, 2007: Results of a Household Survey. Social Care Statistics 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2. The economic and social costs of mental health problems in 2009/10. Centre for Mental Health 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:617–27. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ruscio AM, Brown TA, Chiu WT, et al. Social fears and social phobia in the USA: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychol Med 2008;38:15–28. 10.1017/S0033291707001699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grant BF, Hasin DS, Blanco C, et al. The epidemiology of social anxiety disorder in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:1351–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:617–27. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:593–602. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wittchen HU, Fehm L. Epidemiology and natural course of social fears and social phobia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2003;417:4–18. 10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s417.1.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yonkers KA, Dyck IR, Keller MB. An eight-year longitudinal comparison of clinical course and characteristics of social phobia among men and women. Psychiatr Serv 2001;52:637–43. 10.1176/appi.ps.52.5.637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Health NCCfM. Social anxiety disorder: recognition, assessment and treatment. National Clinical Guideline Number 159 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heimberg RG, Dodge CS, Hope DA, et al. Cognitive behavioral group treatment for social phobia: Comparison with a credible placebo control. Cognit Ther Res 1990;14:1–23. 10.1007/BF01173521 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blanco C, Heimberg RG, Schneier FR, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of phenelzine, cognitive behavioral group therapy, and their combination for social anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:286–95. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cavanagh K. Geographic inequity in the availability of cognitive behavioural therapy in England and Wales: a 10-year update. Behav Cogn Psychother 2014;42:1–5. 10.1017/S1352465813000568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Lindefors N. Cognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost–effectiveness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2012;12:745–64. 10.1586/erp.12.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hedman E, Andersson G, Ljótsson B, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy vs. cognitive behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. PLoS One 2011;6:e18001 10.1371/journal.pone.0018001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hedman E, Andersson E, Ljótsson B, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy vs. cognitive behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: results from a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 2011;49:729–36. 10.1016/j.brat.2011.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Titov N, Andrews G, Johnston L, et al. Shyness programme: longer term benefits, cost-effectiveness, and acceptability. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2009;43:36–44. 10.1080/00048670802534424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hedman E, El Alaoui S, Lindefors N, et al. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of Internet- vs. group-based cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder: 4-year follow-up of a randomized trial. Behav Res Ther 2014;59:20–9. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia Diagnosis Social phobia: assessment and treatment. Guilford press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Carlbring P, Gunnarsdóttir M, Hedensjö L, et al. Treatment of social phobia: randomised trial of internet-delivered cognitive-behavioural therapy with telephone support. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:123–8. 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tillfors M, Carlbring P, Furmark T, et al. Treating university students with social phobia and public speaking fears: Internet delivered self-help with or without live group exposure sessions. Depress Anxiety 2008;25:708–17. 10.1002/da.20416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Heimberg RG,. Becker RG. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Basic mechanisms and clinical strategies. Guilford Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23. EuroQol-Group. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life.. Health Policy 1990;16(3:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kaplan RS, Anderson SR. Time-driven activity-based costing. Harv Bus Rev 2004;82:131-8–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Drummond MF. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nixon RM, Wonderling D, Grieve RD. Non-parametric methods for cost-effectiveness analysis: the central limit theorem and the bootstrap compared. Health Econ 2010;19:316–33. 10.1002/hec.1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fenwick E, O’Brien BJ, Briggs A. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves--facts, fallacies and frequently asked questions. Health Econ 2004;13:405–15. 10.1002/hec.903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Glick HA, Briggs AH, Polsky D. Quantifying stochastic uncertainty and presenting results of cost-effectiveness analyses. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2001;1:25–36. 10.1586/14737167.1.1.25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hedman E, Andersson E, Ljótsson B, et al. Clinical and genetic outcome determinants of Internet- and group-based cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2012;126:126–36. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01834.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Lindefors N. Cognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2012;12:745–64. 10.1586/erp.12.67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Andrews G, Davies M, Titov N. Effectiveness randomized controlled trial of face to face versus Internet cognitive behaviour therapy for social phobia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2011;45:337–40. 10.3109/00048674.2010.538840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Andersson G, Cuijpers P, Carlbring P, et al. Guided Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry 2014;13:288–95. 10.1002/wps.20151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Eldenburg L, Krishan R. Management accounting and control in health care: an economic perspective : Chapman C, Hopwood A, Shields M, Handbook of management accounting research. Elsevier, 2007:859–83. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kaplan RS, Porter ME. How to Solve The Cost Crisis In Health Care. Harvard Bus Rev 2011;89:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. McLaughlin N, Burke MA, Setlur NP, et al. Time-driven activity-based costing: a driver for provider engagement in costing activities and redesign initiatives. Neurosurg Focus 2014;37:E3 10.3171/2014.8.FOCUS14381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Briggs AH, O’Brien BJ. The death of cost-minimization analysis? Health Econ 2001;10:179–84. 10.1002/hec.584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dakin H, Wordsworth S. Cost-minimisation analysis versus cost-effectiveness analysis, revisited. Health Econ 2013;22:22–34. 10.1002/hec.1812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.