Abstract

Objective

To characterise incidence and healthcare costs associated with persistent postoperative pain (PPP) following lumbar surgery.

Design

Retrospective, population-based cohort study.

Setting

Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) and Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) databases.

Participants

Population-based cohort of 10 216 adults who underwent lumbar surgery in England from 1997/1998 through 2011/2012 and had at least 1 year of presurgery data and 2 years of postoperative follow-up data in the linked CPRD–HES.

Primary and secondary outcomes measures

Incidence and total healthcare costs over 2, 5 and 10 years attributable to persistent PPP following initial lumbar surgery.

Results

The rate of individuals undergoing lumbar surgery in the CPRD–HES linked data doubled over the 15-year study period, fiscal years 1997/1998 to 2011/2012, from 2.5 to 4.9 per 10 000 adults. Over the most recent 5-year period (2007/2008 to 2011/2012), on average 20.8% (95% CI 19.7% to 21.9%) of lumbar surgery patients met criteria for PPP. Rates of healthcare usage were significantly higher for patients with PPP across all types of care. Over 2 years following initial spine surgery, the mean cost difference between patients with and without PPP was £5383 (95% CI £4872 to £5916). Over 5 and 10 years following initial spine surgery, the mean cost difference between patients with and without PPP increased to £10 195 (95% CI £8726 to £11 669) and £14 318 (95% CI £8386 to £19 771), respectively. Extrapolated to the UK population, we estimate that nearly 5000 adults experience PPP after spine surgery annually, with each new cohort costing the UK National Health Service in excess of £70 million over the first 10 years alone.

Conclusions

Persistent pain affects more than one-in-five lumbar surgery patients and accounts for substantial long-term healthcare costs. There is a need for formal, evidence-based guidelines for a coherent, coordinated management strategy for patients with continuing pain after lumbar surgery.

Keywords: Persistent post-operative pain (PPP), Failed Back Surgery Syndrome (FBSS), lumbar surgery, clinical practice research datalink (cprd), hospital episode statistics (hes)

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to estimate the occurrence of postoperative pain (PPP) following lumbar surgery using a sample of surgical patients selected from routinely collected UK hospital and primary care data.

Our estimates of healthcare usage and costs are based on real-world experiences of the full range of lumbar surgery patients found in clinical practice.

A limitation of using electronic medical records data is the classification of patients with PPP as there is no specific diagnosis code or set of codes for the condition of PPP and our data do not contain information on pain scores commonly used to assess the existence and severity of chronic pain following recovery from surgery.

In contrast with previous studies that have relied on multiple assumptions regarding treatment patterns or on small and/or non-representative patient samples, we were able to calculate more precise estimates of PPP following lumbar surgery.

Introduction

Persistent postoperative pain (PPP) in lumbar surgery patients—more commonly known as failed back surgery syndrome—refers to chronic back and/or leg pain that continues or recurs in some patients following spinal surgery. It may be caused by one or a combination of factors including: residual or recurrent disc herniation, persistent postoperative compression of a spinal nerve, altered joint mobility, joint instability, postoperative myofascial pain development, scar tissue (fibrosis) and/or spinal muscular deconditioning.1–3 Psychosocial factors that have been identified in this and other chronic postsurgical pain conditions include preoperative anxiety, depression, poor coping strategies and pain catastrophising. Litigation and worker’s compensation have also been associated with reports of ongoing pain.4 5 Patients form a diverse group, with complex and varied aetiologies and symptoms.6 7

Authoritative publications, mainly large case series and clinical trials, report that 10%–40% of all patients who undergo lumbar surgery develop some form of chronic PPP.8–16 The wide range of estimates reported reflect varying clinical experiences of different institutions and the small samples of patients on which these estimates are based. In 2013, Thompson took a mid-range estimate of 20% failure applied to a rate of lumbar surgery in the UK population of 5 per 10 000 people and concluded that there are approximately 6000 new cases of PPP following spine surgery in the UK every year.17 More precise estimates for the UK are not available.

Up-to-date, population-based estimates of incidence are required to keep pace with surgical advances and to inform healthcare system spending in this population. Using a formal and more rigorous epidemiological data-driven approach, we aim to provide robust estimates of the incidence and healthcare costs associated with PPP following lumbar surgery in the UK over a 15-year period, from 1997/1998 to 2011/2012.

Methods

Setting and data sources

This study employs a retrospective cohort design using two linked UK databases: the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database and UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). An online supplementary appendix provides more detail on these data. Approval was granted by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee for Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency on 17 December 2014 (ISAC Protocol 14-180R).

bmjopen-2017-017585supp001.doc (84KB, doc)

Study participants

Incidence of lumbar surgery was calculated on a patient basis, as the number of patients aged 18 and above who underwent one or more lumbar procedures in a given fiscal year, expressed as a rate per 10 000 adults in the CPRD–HES linked dataset. Index-operative procedures included any single procedure or combination of discectomy/microdiscectomy, excision of lumbar intervertebral disc, laminectomy, foraminotomy, lumbar decompression (or fenestration) or lumbar fusion (including all anterior and posterior approaches as well as combined approaches). Patients were required to have at least 2 years of follow-up data to allow sufficient time to observe criteria for PPP following the index surgery.

Definition of persistent PPP

From our lumbar surgery cohort, we categorised each individual as a ‘success’ (ie, no evidence of PPP) or ‘failure’ (ie, evidence of PPP). Any one of the following three criteria, alone or in combination, was taken as evidence of pain continuing past the expected period for recovery following index lumbar surgery:

any additional lumbar surgery of any type occurring between 6 and 24 months postindex surgery;

a minimum of one pain-related physician visit in each of two consecutive quarters at any point during the 6–24 months postindex surgery identified using READ codes in CPRD or treatment specialty codes in the HES outpatient file;

any other surgical intervention (eg, neuromodulation, implantation of a drug infusion delivery system) to address pain occurring at any time, not limited to 24 months after the index surgery, identified from either CPRD or the HES inpatient or outpatient datasets.

Prescription of analgesics (including opioids, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antidepressants or anticonvulsants/antiepileptic drugs used for pain and other analgesic therapies for a period of at least 6 months from 6 to 24 months postindex) was not by itself considered evidence of persistent PPP as patients may be prescribed analgesics for other painful conditions.

A minimum period of 3 months has been proposed for tissue healing after surgery, and this time period is also used to define chronicity of pain.18–20 We applied a more stringent, minimum 6-month period after the index lumbar surgery for patients to recover from normal, expected PPP. Any additional spine surgery that occurred during that period was assumed to be related to surgical complications of the index lumbar procedure, rather than the treatment of PPP. The literature suggests that some patients initially appear to improve following lumbar surgery but later become increasingly bothered by pain.4 6 21 Therefore, we allowed for a period of 18 months (6–24 months postindex surgery) over which to evaluate evidence of unresolved, chronic pain based on recorded ongoing interventions.

Healthcare usage and costs

A standard cost-of-illness approach22 23 was taken to estimate total healthcare costs from the perspective of the UK National Health Service (NHS). We classified all healthcare encounters into major categories of healthcare resource usage and assigned unit costs following standard practice for cost-of-illness and cost-effectiveness research (see online supplementary information on cost methodology and unit cost tables). Consistent with other studies of resource usage among similar populations,24 we estimated total cost per patient over 24 months for all patients in our study (excluding the cost of the index surgery). We then extended our analysis out to 5 and 10 years postindex surgery among the subsets of patients with sufficient follow-up data. To account for inflation and variations in pricing over time, 2013 unit costs were applied to all years. Total costs incorporated direct (including medical staff), indirect and overhead costs paid by the NHS. Finally, using these per patient estimates, we projected the total number of PPP cases in the UK annually and the associated costs to the NHS.

bmjopen-2017-017585supp002.pdf (1MB, pdf)

Statistical analyses

To estimate rates of PPP, we computed the number of patients who met our criteria for PPP as a percentage of all patients who underwent initial lumbar surgery within the time frame.

The comparison group of no persistent PPP was drawn from among lumbar surgery patients who fulfilled the ‘no PPP’ criteria. We used 1:1 propensity score matching (without replacement) based on patient’s age at surgery, gender, year in which surgery took place, type of initial surgery (fusion vs decompression) and presence of each of 17 comorbidities that comprise the Charlson Comorbidity index (CCI) using the greedy matching algorithm.25–27

We estimated healthcare usage over a 2-year period for patients with PPP versus the matched controls and presented: (1) the proportion of patients who had a non-zero healthcare resource usage and the number of encounters by category (ie, primary care, inpatient care, outpatient attendances, outpatient procedures, accident and emergency care and prescriptions for pain medications) and (2) costs among users of the respective type of services/events (in order to provide insight into the intensity of resource usage among users of these services). Next, we estimated total healthcare costs by category of healthcare usage for all patients. Finally, we estimated the cost attributable to PPP as the difference in total costs for all PPP patients versus no PPP controls over the time periods 2, 5 and 10 years postindex surgery.

Statistical significance of differences between patients with and without PPP were evaluated using Fisher's exact tests for categorical predictor variables and Wilcoxon tests for continuous predictor variables. The main analyses compared the matched PPP cases and controls using Fisher’s exact tests for healthcare usage and bootstrapping for differences in average costs. All data manipulation and analyses were conducted using SAS software, V.9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute).

Sensitivity analysis

In sensitivity analyses, we adjusted costs using generalised linear models (using log link and gamma distribution), extended estimating equations and ordinary least squares.

Results

Rates of lumbar surgery in HES (among patients with linked CPRD data)

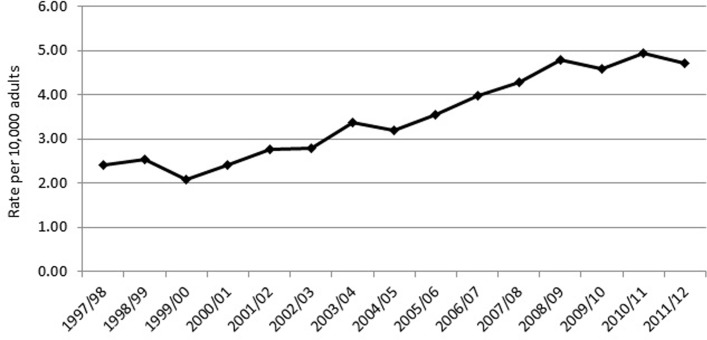

From the linked CPRD–HES database, we identified 10 216 adults who underwent lumbar surgery from fiscal years 1997/1998 through 2011/2012 and who had at least 12 months of presurgery data (used to identify presurgical comorbid conditions and exclude those with previous lumbar surgery) and with 24 months follow-up. Our denominator for each year included all patients within the linked CPRD/HES dataset with at least 36 months of follow-up to be comparable with the lumbar surgery group in that year. Incidence of PPP was adjusted to reflect the age and sex distribution of the UK population in each year of the study.28 The age-adjusted/sex-adjusted rate of lumbar surgeries grew steadily from 2.41 per 10 000 in 1997/1998 to reach a peak of 4.94 per 10 000 in 2010/2011 before falling slightly in 2011/2012 to 4.70 per 10 000 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Age-adjusted and sex-adjusted incidence of lumbar surgery in linked Clinical Practice Research Datalink–Hospital Episode Statistics, rates per 10 000 adults.

Percentage of lumbar surgery patients with persistent PPP (cases)

Of the 10 216 adults undergoing lumbar surgery in fiscal years 1997/1998–2011/2012, 1756 (17.2%; 95% CI 16.5% to 17.9%) patients met our criteria for PPP. Among patients with PPP, 85.4% were prescribed pain medication for at least 6 months compared with 50.3% of patients who did not meet PPP criteria.

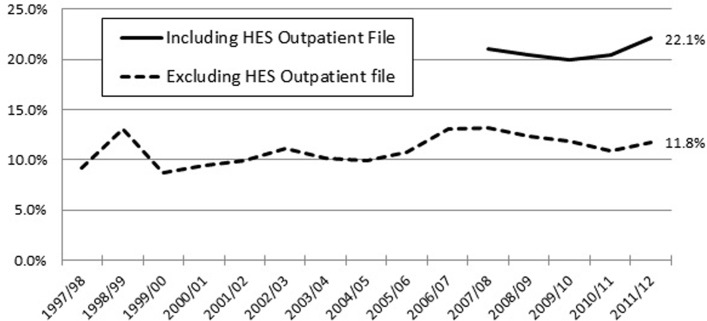

Figure 2 shows the impact on our estimates of PPP from including the HES outpatient data, available from 2008 onwards. The dotted line includes patients identified as having PPP using only the CPRD general practice file plus HES inpatient file. The solid line includes patients identified using these files plus the HES outpatient file, accredited as a National Statistic since 2008. The percentage of patients with PPP captured without the HES outpatient file was fairly stable over the entire 15-year study period, but doubles with the inclusion of HES outpatient data. The percentage of patients with PPP early in the study period is likely to be underestimated as hospital pain clinic visits were not recorded. The more recent data are more likely to be reflective of current UK practice. On average, over the most recent 5-year period, 20.8% (95% CI 19.7% to 21.9%) of eligible patients met our criteria for PPP.

Figure 2.

Percentage of patients with postoperative pain (PPP) by year of index lumbar surgery. HES, Hospital Episode Statistics.

PPP cases versus lumbar surgery patients without PPP

Prior to matching, a comparison of patients with PPP versus those without showed that PPP patients were younger, more likely to be female and have a slightly higher comorbidity burden, as measured by the CCI. After propensity score matching, as expected, there were no significant differences between the cases and controls (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of lumbar surgery patients with and without postoperative pain (PPP) before and after selecting propensity score matched control group

| Before matching | After matching | |||||

| No PPP | PPP | p Value | No PPP | PPP | p Value | |

| n=8460 | n=1756 | n=1756 | n=1756 | |||

| Age at surgery (years), mean (SD) | 53.6 (16.0) |

52.9 (15.5) |

0.044 | 52.1 (16.0) |

52.9 (15.5) |

0.16 |

| Male, % | 50.7 | 43.3 | <0.001 | 43.0 | 43.3 | 0.86 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean (SD) | 1.1 (2.0) |

1.2 (2.0) |

0.002 | 1.1 (1.8) |

1.2 (2.0) |

0.06 |

p Values were based on Fisher's exact tests for categorical and Wilcoxon tests for continuous variables.

Healthcare usage and cost

Compared with patients without, those with PPP had significantly increased rates of healthcare usage for all healthcare encounter types. The difference was the largest for inpatient hospital care at 77.5% for those with PPP versus 44.9% for those without. Patients with PPP were more than twice as likely as those without PPP to have had two or more inpatient stays in the 2 years following index surgery.

Among those who used care in each of these settings, costs were in most cases significantly greater in the presence of PPP. In particular, PPP was associated with a threefold increase in average pain medication costs (£1165 versus £382). Greater costs were also observed in inpatient, outpatient hospital and primary care settings, indicating greater intensity of resource usage for patients with PPP in each of these settings (table 2).

Table 2.

Healthcare resource use and costs (2013 British pounds) in the 2-year period following index surgery among users of services, cases (postoperative pain (PPP)) versus propensity score matched controls (no PPP)

| Healthcare usage | Costs among users only | |||

| No PPP (n=1756) | PPP (n=1756) | No PPP | PPP | |

| n (%) | n (%) | mean (SD) | mean (SD) | |

| Any inpatient | 788 (44.9) | 1361 (77.5)** | £3678 (4520) | £5357 (5282)** |

| 0 | 968 (55.1) | 395 (22.5) | ||

| 1 | 377 (21.5) | 484 (27.6) | ||

| 2 | 192 (10.9) | 351 (20.0) | ||

| >2 | 219 (12.5) | 526 (29.9) | ||

| Any outpatient attendances | 1510 (86.0) | 1606 (91.5)** | £783 (975) | £1316 (1149)** |

| 0 | 246 (14.0) | 150 (8.5) | ||

| 1–6 | 904 (51.5) | 438 (24.9) | ||

| 7–12 | 349 (19.9) | 512 (29.2) | ||

| >12 | 257 (14.6) | 656 (37.4) | ||

| Any outpatient procedures | 435 (24.8) | 583 (33.2)** | £540 (817) | £664 (875)* |

| 0 | 1321 (75.2) | 1173 (66.8) | ||

| 1 | 203 (11.6) | 221 (12.6) | ||

| 2 | 86 (4.9) | 116 (6.6) | ||

| >2 | 146 (8.3) | 246 (14.0) | ||

| Any accident and emergency | 325 (18·5) | 484 (27·6)** | £257 (193) | £265 (213) |

| 0 | 1431 (81.5) | 1272 (72.4) | ||

| 1 | 205 (11.7) | 306 (17.4) | ||

| 2 | 67 (3·8) | 94 (5·4) | ||

| >2 | 53 (3.0) | 84 (4.8) | ||

| Any primary care | 1751 (99.7) | 1756 (100.0)* | £3178 (2560) | £4616 (3011)** |

| Number of primary care visits, mean (SD) | 73.3 (57.8) | 107.5 (68.3) | ||

| Any pain drugs | 1699 (96.7) | 1750 (99.7)** | £382 (2348) | £1165 (4349)** |

| Number of prescriptions, mean (SD) | 70.1 (98.6) | 104.9 (104.0) | ||

*p< 0.05 and **p<0.01 comparing rates of healthcare use (using Fisher’s exact tests) and mean costs (based on bootstrapping) among patients with PPP versus no PPP.

Comparing total costs for patients with PPP versus matched controls (no PPP) including both users and non-users of each service, we found that the mean additional cost attributable to PPP in the 2 years following surgery was £5383 per patient (table 3). Inpatient costs accounted for almost half (46.5%) of the cost differential and primary care contributed 26.9%.

Table 3.

Total 2-year costs (2013 British pounds), cases (postoperative pain (PPP)) versus propensity score matched control cohort (no PPP)

| No PPP (n=1756) Mean (SD) |

PPP (n=1756) Mean (SD) |

Difference | (95% CIs) | |

| Inpatient | £1651 (3537) | £4152 (5160) | £2501 | (2202 to 2811) |

| Outpatient attendances | £673 (944) | £1204 (1159) | £531 | (456 to 604) |

| Outpatient procedures | £134 (469) | £221 (593) | £87 | (51 to 121) |

| Accidents and emergency | £48 (130) | £73 (163) | £25 | (15 to 35) |

| Primary care | £3169 (2562) | £4616 (3011) | £1447 | (1263 to 1661) |

| Pain medications | £370 (2310) | £1161 (4342) | £791 | (574 to 1027) |

| Total costs | £6044 (6712) | £11 427 (9304) | £5383 | (4872 to 5916) |

When costs estimates were extended to 5 and 10 years following the index lumbar surgery, among patients with sufficient follow-up data for each period, the difference in costs between patients with and without PPP increased. In total, over 5 years following surgery, patients with PPP (n=894 cases) cost an additional mean of £10 195 (95% CI 8726 to 11 669), rising to a total mean cost differential of £14 318 (95% CI 8386 to 19 771) over 10 years (n=186 cases). Note that the difference may have been underestimated for patients who underwent surgery prior to the release of the HES outpatient files in 2003/2004.

Sensitivity analyses

Estimating the PPP cost differential with generalised linear models (using log link and gamma distribution), extended estimating equations and ordinary least squares produced very similar results to the main analysis.

Discussion

A total of 10 216 adults identified within the linked CPRD–HES database underwent lumbar spinal surgery between 1997/1998 and 2011/2012, with the rate of individuals receiving surgery approximately doubling over this time period. Using the criteria of additional lumbar surgery within 6–24 months, pain-related physician visits over at least two consecutive quarters within the same period or other surgical intervention therapy at any time, we estimate that approximately one in five (20.8%; 95% CI 18.5% to 23.0%) lumbar spine surgery patients in the UK experience persistent PPP within 2 years of their index surgery. The costs of PPP patients over 10 years following lumbar surgery were more than 50% higher compared with those patients without ongoing pain.

Our estimate of PPP was conservative in that we did not include patients who had ongoing prescriptions for analgesic pain medications in the absence of other more rigorous indicators of back pain. If we had included any prescribing of pain medication, our estimate of postlumbar surgery PPP incidence would have risen from 20.8% to 61.8%.

Our incidence estimate is consistent with a recent large Japanese study. Using internet-based survey data, the authors found that among 1842 respondents who self-reported having undergone lumbar surgery in the past 10 years, 20.6% experienced ongoing pain.29

Strengths and limitations of this study

This study used routinely captured hospital and primary care data to investigate diagnoses and treatment patterns on a population sample of lumbar surgery patients. Hence, our observations are based on patterns of care for a large and representative group of patients undergoing treatment in real-world settings. This enabled us to calculate more precise estimates of PPP following lumbar surgery; previous studies have relied on multiple assumptions regarding treatment patterns or on randomised controlled clinical trial data with small, non-representative patient samples.

A limitation of using electronic medical records data is the classification of patients with PPP. There is no specific diagnosis code or set of codes for the condition of PPP. Instead, our estimates are based on presentation for further interventions, surgery and/or attendance at specialist pain clinics. The data do not contain information on pain scores commonly used to assess the existence and severity of chronic pain following recovery from surgery. Evidence on the persistence of pain for a period of at least 6 months in the year following surgery was, by necessity, inferred from data on receipt of therapies for chronic pain, referrals to pain specialists, etc. It is possible that some patients who had a successful outcome of back surgery experienced ongoing concurrent or new onset chronic pain from another source and were misclassified as having postlumbar PPP.

Implications of our findings for policy and/or practice

Our findings are based on a broadly representative sample of the UK population undergoing lumbar surgery. The mid-2012 population estimate of adults in the UK was 50.2 million.30 Based on our estimates of lumbar surgery, we would predict that approximately 23 592 patients underwent initial lumbar surgery in the UK at the end of our study period. This equates to 4907 adults (20.8%) with PPP following lumbar surgery annually in the UK and that the associated short-term (2 years) costs of caring for PPP amount to approximately £26.4 million for each new annual cohort of PPP patients. Extending our horizon to cover 10 years following index surgery, we would predict that each new annual cohort of lumbar surgery patients experiencing PPP could cost the NHS approximately £70.3 million over the first decade, with costs likely to continue accumulating over the remainder of the lifespan of members of that cohort.

Despite these large and ongoing costs, no formal guidelines to date have been put forward for the treatment of persistent pain after lumbar surgery. Our findings for patients with available follow-up data for 2, 5 and 10 years postoperatively suggest that PPP patients have significantly higher resource usage and that these costs continue for at least a decade following index surgery. Although our data contained too few patients with more than 10 years of follow-up to extend our estimates beyond the initial decade, it is likely that the PPP cost differential persists into the long term particularly as patients’ age. Our 10-year estimate is a censored estimate of the total lifetime cost of managing these patients.

The growth in rates of lumbar surgery suggests that the numbers of patients living with ongoing pain in the UK is substantial and growing. In addition to the NHS cost burden, we know from other studies that these patients experience significant reduction in health-related quality of life. For example, in the PROCESS study, mean baseline EQ5D index score among lumbar surgery patients with ongoing pain was 0.14,31 which is much lower than has been documented for other patient populations with chronic diseases, including cancer.32 There is a need for a coherent management strategy for primary care staff, pain specialists and surgeons to offer to these patients. High-quality primary studies are urgently required to provide more understanding of the treatment and recovery trajectory of this patient group.

Conclusion

Using routinely collected clinical data, this study shows that approximately one-in-five lumbar spine surgery patients in the UK experience PPP (also known as ‘failed back surgery syndrome’). PPP is associated with higher rates of resource usage and with increased intensity of resource use in the inpatient, outpatient and primary care settings. The costs to the NHS of treating patients with PPP are substantive and remain elevated over time, highlighting the need for formalised national guidelines for the management of patients with lumbar pain presurgery and postsurgery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Medtronic International Trading Sàrl, Switzerland, for providing funding. Funke Stauble and Shanti Thavaneswaran brought together the study team and supported the research process.

Footnotes

Contributors: SE, AM, RT and SW conceived and designed the study originally. JB and DC joined the study team part way through the analysis planning phase and helped to shape the final study design. SW acquired the data. CNC, T-CK, MS, TST and SW developed the analysis plan. T-CK, MS and SW analysed the data. SW drafted the manuscript. JB, DC, SE, T-CK, AM, MS, RT, TST and SW revised the manuscript. All authors contributed intellectually to the interpretation of the data, participated in manuscript development and approved the final version. SW is the guarantor.

Funding: This study was supported by Medtronic International Trading Sàrl, Switzerland.

Disclaimer: This study was based in part on data from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink obtained under license from the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. However, the interpretation and conclusions contained in this study are those of the authors alone.

Competing interests: At the time of the study, CNC was employed by PHMR, LLC, who received consulting fees from Medtronic. SW, MS and T-CK received consulting fees from PHMR, LLC. RT, AM, JB, DC and SE received consulting fees from Medtronic as advisors to the project.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: Independent Scientific Advisory Committee for Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA)

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hazard RG. Failed back surgery syndrome: surgical and non-surgical approaches. Clin Orthop Relat R 2006;443:228–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buyten J-P, Linderoth B. “The failed back surgery syndrome”: definition and therapeutic algorithms - an update. Eur J Pain Suppl 2010;4:273–86. 10.1016/j.eujps.2010.09.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bokov A, Isrelov A, Skorodumov A, et al. An analysis of reasons for failed back surgery syndrome and partial results after different types of surgical lumbar nerve root decompression. Pain Physician 2011;14:545–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan CW, Peng P. Failed back surgery syndrome. Pain Med 2011;12:577–606. 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01089.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Theunissen M, Peters ML, Bruce J, et al. Preoperative anxiety and catastrophizing: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the association with chronic postsurgical pain. Clin J Pain 2012;28:819–41. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31824549d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slipman CW, Shin CH, Patel RK, et al. Etiologies of failed back surgery syndrome. Pain Med 2002;3:200–14. discussion 214–7 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2002.02033.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tharmanathan P, Adamson J, Ashby R, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of failed back surgery syndrome in the UK: mapping of practice using a cross-sectional survey. Br J Pain 2012;6:142–52. 10.1177/2049463712466321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yorimitsu E, Chiba K, Toyama Y, et al. Long-term outcomes of standard discectomy for lumbar disc herniation: a follow-up study of more than 10 years. Spine 2001;26:652–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Javid MJ, Hadar EJ. Long-term follow-up review of patients who underwent laminectomy for lumbar stenosis: a prospective study. J Neurosurg 1998;89:1–7. 10.3171/jns.1998.89.1.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrews DW, Lavyne MH. Retrospective analysis of microsurgical and standard lumbar discectomy. Spine 1990;15:329–35. 10.1097/00007632-199004000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caspar W, Campbell B, Barbier DD, et al. The Caspar microsurgical discectomy and comparison with a conventional standard lumbar disc procedure. Neurosurgery 1991;28:78–87. 10.1227/00006123-199101000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frymoyer JW, Hanley E, Howe J, et al. Disc excision and spine fusion in the management of lumbar disc disease. A minimum ten-year followup. Spine 1978;3:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ross JS, Robertson JT, Frederickson RC, et al. Association between peridural scar and recurrent radicular pain after lumbar discectomy: magnetic resonance evaluation. ADCON-L European study group. Neurosurgery 1996;38:855–63. 10.1227/00006123-199604000-00053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fritsch EW, Heisel J, Rupp S. The failed back surgery syndrome: reasons, intraoperative findings, and long-term results: a report of 182 operative treatments. Spine 1996;21:626–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.North RB, Kidd DH, Zahurak M, et al. Spinal cord stimulation for chronic, intractable pain: experience over two decades. Neurosurgery 1993;32:384–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilkinson HA. The failed back syndrome: etiology and therapy. Philadelphia: Harper & Row, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomson S. Failed back surgery syndrome - definition, epidemiology and demographics. Br J Pain 2013;7:56–9. 10.1177/2049463713479096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.International association for the study of pain. Classification of chronic pain. Second Edition http://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1673&navItemNumber=677 (accessed 20 Jun 2016).

- 19.Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet 2006;367:1618–25. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68700-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Macrae WA. Chronic post-surgical pain: 10 years on. Br J Anaesth 2008;101:77–86. 10.1093/bja/aen099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussain A, Erdek M. Interventional pain management for failed back surgery syndrome. Pain Pract 2014;14:64–78. 10.1111/papr.12035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akobundu E, Ju J, Blatt L, et al. Cost-of-illness studies : a review of current methods. Pharmacoeconomics 2006;24:869–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jefferson T, Demicheli V, Mugford M, et al. ; Elementary economic evaluation in health care. 2nd edn London: BMJ publishing group, 2000:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adogwa O, Owens R, Karikari I, et al. Revision lumbar surgery in elderly patients with symptomatic pseudarthrosis, adjacent-segment disease, or same-level recurrent stenosis. Part 2. A cost-effectiveness analysis: clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine 2013;18:147–53. 10.3171/2012.11.SPINE12226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manca A, Austin PC. Using propensity score methods to analyse individual patient‐level cost‐effectiveness data from observational studies. York, UK: university of york HEDG working paper No. 08/, 2008. http://www.york.ac.uk/res/herc/research/hedg/wp.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsons LS. Reducing bias in a propensity score matched-pair sample using greedy matching techniques SAS Users group international 26 (SUGI26, 2001:214–26. http://www2.sas.com/proceedings/sugi26/p214-26.pdf (accessed 16 Oct 2016).

- 27.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83. 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National cancer institute. SEER stat tutorials: calculating age-adjusted rates. https://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/tutorials/aarates/definition.html (accessed 28 Oct 2016).

- 29.Inoue S, Kamiya M, Nishihara M, et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and burden of failed back surgery syndrome: the influence of various residual symptoms on patient satisfaction and quality of life as assessed by a nationwide Internet survey in Japan. J Pain Res 2017;10:811–23. 10.2147/JPR.S129295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Office for National Statistics (ONS). Population estimates for UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (Mid-2012 file). https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/populationestimatesforukenglandandwalesscotlandandnorthernireland (accessed 28 Dec 2016).

- 31.Manca A, Kumar K, Taylor RS, et al. Quality of life, resource consumption and costs of spinal cord stimulation versus conventional medical management in neuropathic pain patients with failed back surgery syndrome (PROCESS trial). Eur J Pain 2008;12:1047–58. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doth AH, Hansson PT, Jensen MP, et al. The burden of neuropathic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of health utilities. Pain 2010;149:338–44. 10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017585supp001.doc (84KB, doc)

bmjopen-2017-017585supp002.pdf (1MB, pdf)