Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the cost-effectiveness of a planned birth in a birth centre compared with alternative planned places of birth for low-risk women. In addition, a distinction has been made between different types of locations and integration profiles of birth centres.

Design

Economic evaluation based on a prospective cohort study.

Setting

21 Dutch birth centres, 46 hospital locations where midwife-led birth was possible and 110 midwifery practices where home birth was possible.

Participants

3455 low-risk women under the care of a community midwife at the start of labour in the Netherlands within the study period 1 July 2013 to 31 December 2013.

Main outcome measures

Costs and health outcomes of birth for different planned places of birth. Healthcare costs were measured from start of labour until 7 days after birth. The health outcomes were assessed by the Optimality Index-NL2015 (OI) and a composite adverse outcomes score.

Results

The total adjusted mean costs for births planned in a birth centre, in a hospital and at home under the care of a community midwife were €3327, €3330 and €2998, respectively. There was no difference between the score on the OI for women who planned to give birth in a birth centre and that of women who planned to give birth in a hospital. Women who planned to give birth at home had better outcomes on the OI (higher score on the OI).

Conclusions

We found no differences in costs and health outcomes for low-risk women under the care of a community midwife with a planned birth in a birth centre and in a hospital. For nulliparous and multiparous low-risk women, planned birth at home was the most cost-effective option compared with planned birth in a birth centre.

Keywords: economic evaluation, birth centre, maternity care, optimality index

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This economic evaluation, in which we estimated the costs and health outcomes for a planned birth in a birth centre, in a hospital and at home, took the form of a cost-effectiveness analysis from a healthcare perspective.

This study has a high participation rate as regard to birth centres (21 out of 23), which reduces the chance of bias.

Sensitivity analyses, using different prices, produced similar results and conclusions to those of the original generalised linear model on costs, in other words, the impact of systematic errors (bias) was low.

In the literature on cost-effectiveness analyses, only two treatments have to date been compared using the net benefit regression framework. This study is an initial attempt to expand the framework from two to three treatments.

A problem concerning all (Dutch) studies comparing places of birth is that women in these places are all different and it is not possible to adjust completely for this. The minor differences found in this study may therefore be the result of differences between the women rather than between the settings.

Introduction

The Dutch maternity care system is based on risk attribution: independent community midwives providing care for low-risk pregnant women (primary care) and obstetricians providing in-hospital care for high-risk women (secondary care). The risk attribution with reasons for consultation and referral are set out in a multidisciplinary guideline: the List of Obstetric Indications.1 Low-risk pregnant women can choose where they want to give birth: at home, in a hospital or in a birth centre. The community midwife assists them during natal care, pregnancy and the postpartum period. Most midwives work in group practices in the community and they are autonomous as regard to their actions and decisions.2 If a pregnant woman’s risk status changes during her pregnancy or labour or she requests pharmacological pain relief, she will be referred from primary care to secondary care.

Over the past decade, fewer women planned to give birth at home. In 2004, around 48% of all low-risk births in the Netherlands were planned at home; in 2014 this number fell to 24%.3 As most low-risk women in the Netherlands are now planning to give birth outside their home, it is necessary to offer these women a good alternative. Birth centres are a relatively new phenomenon in the Netherlands and most of them have been established in the last decade. Birth centres are regarded as settings where women with low-risk pregnancies can give birth in a home-like environment, supervised by a community midwife. When complications arise or pharmacological pain relief is requested, referral to an obstetrician/paediatrician is needed.4–6 During birth the community midwife is assisted by a maternity care assistant. This assistant provides care and support for the mother and her baby for up to 8 days after birth, in a birth centre or at home.

The costs and health outcomes of the different birth settings in the Netherlands (i.e., hospital and home) for low-risk women have been widely discussed in recent years,7–11 especially since the national perinatal mortality rate was shown to be one of the highest in Europe.12 The results of the studies were linked directly to the operational set-up of the Dutch maternity care system, with its clear segmentation of primary (community midwife-led) and secondary care (obstetrician-led) and lack of collaboration. It is, however, assumed that birth centres provide a better quality of care when compared with the existing system of primary and secondary care. One reason for this may be that colocation of birth centres and obstetric units is an enabler for better collaboration.13 At present, there is no evidence for this assumption.

A Dutch study found that the total costs associated with pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum care are comparable for home birth and hospital birth under the care of a community midwife.14 Evidence relating to costs and health outcomes of all Dutch low-risk birth settings, including birth centres, is still lacking. The costs and health outcomes of birth-centre care have been studied internationally. In England, planned birth at home is the most cost-effective option compared with planned birth in an alongside or freestanding midwifery unit and an obstetric unit.15 The results of other studies on costs and health outcomes of midwifery-attended births in England, the USA and Australia were comparable to the British study.16–21

However, the outcomes of these studies cannot easily be generalised to the Netherlands, since the Dutch system is different, with a relatively high rate of home births and a low rate of medical interventions compared with other high-income countries.7 We therefore studied the costs and health outcomes of Dutch birth-centre care as part of the Dutch Birth Centre study, a national project evaluating the outcomes of Dutch birth centres on aspects such as client and professional experiences, effectiveness and costs.4 The aim of this study is to estimate the cost-effectiveness of planned birth in a birth centre compared with alternative planned places of birth for low-risk women who start labour under the care of a community midwife. In addition, a distinction has been made between different types of locations and integration profiles of birth centres.

Methods

The cohort study included 3455 term low-risk women under the care of a community midwife at the start of labour. The characteristics of these women, the exclusion criteria and the analyses on the health outcomes have been reported in detail elsewhere.22A minimum of three midwifery practices located near a birth centre (n=23) were randomly recruited to collect data. A condition for participation was that the birth centre had been operating for over 6 months before the study period, leading to the exclusion of two birth centres. Midwifery practices in regions where there was the possibility of a midwifery-led hospital birth were recruited to collect data relating to planned midwife-led hospital births. Planned birth at home was an option for women in all participating midwifery practices. The women were recruited from 110 midwifery practices (127 were approached) within the study period 1 July 2013 to 31 December 2013. Twenty-one birth centres and 46 hospital locations where midwife-led birth was possible participated in this study.22

The cohort study compared perinatal and maternal outcomes, according to the intention-to-treat method, by planned place of birth: in a birth centre, in a hospital or at home. The intention-to-treat method is used to prevent distortion in outcomes resulting from selective drop-out in the groups to be investigated. In maternity care research the place of birth is a variable where selective drop-out occurs as a result of referrals to secondary care during childbirth. By analysing the outcomes based on the planned place of birth, the groups remain comparable.23 Separate analyses were performed for different types of birth centres, based on location and based on integration profile. Three types of birth-centre locations can be distinguished: 1) freestanding from a hospital, 2) alongside an obstetric unit and 3) on-site at an obstetric unit.24

We also distinguished three integration profiles: monodisciplinary-oriented birth centres (MOBC), multidisciplinary-oriented birth centres (MUBC) and a mixed group of birth centres (MIBC). Integrated care is increasingly encouraged in maternity care systems.25 The essence of integrated care is a continuum of care for service users, crossing the boundaries of public health, primary, secondary and tertiary care.25–27 The focus of MOBCs is to act as a facility for giving birth rather than to improve collaboration between care providers or to realise integration of care, and MOBCs are mainly owned by primary care organisations. MUBCs can be regarded as facilities for giving birth with a focus on integrated birth care. They have governance structures consisting of both primary and secondary care organisations. The disciplines involved have formulated a joint vision on birth care. The community midwife is still the person who takes care of low-risk pregnant women. MIBCs are a mixed group. They differ more from each other in their organisation than centres in the other groups. Compared with MUBCs these centres had higher scores on clinical integration (the coordination of person-focused care in a single process across time, place and discipline) and lower scores on the other dimensions (professional, organisational, system, functional and normative integration).28

The primary clinical outcomes were measured by an Optimality Index-NL2015 (OI)29 and a composite adverse outcome score (CAO) was used as a secondary outcome measure.30 The OI is a tool used to measure ‘maximum outcome with minimal intervention’, based on the principle of optimality. It contains both process and outcome items and background characteristics are taken into account. The tool is used to compare the extent to which different low-risk groups, with few adverse outcomes, achieve an optimal situation. An optimal situation is a situation that every woman would wish for: a spontaneous, uncomplicated birth after a full-term pregnancy, without interventions, resulting in a healthy mother and baby.31–33 The tool was revised for use in Dutch obstetric research.29 It contains 31 process and outcome items with evidence-based criteria relating to optimality (e.g., duration of first and second stage, instrumental (vaginal) birth, loss of blood during birth, referral during labour or within 2 hours post partum and birth weight). Each item meeting the criteria for optimality was scored as ‘1’. Those considered non-optimal were scored as ‘0’. In this way, a sum score of all 31 items per woman was calculated.31–33 In addition, the CAO, a combined measure of six distinct adverse outcomes (maternal mortality within 42 days of birth, (sub) total rupture, blood loss of more than one litre, perinatal mortality within 7 days of birth, Apgar score below 7 at 5 min after birth, admission to the neonatal intensive care unit within 48 hours of birth) was used. This measure is based on the occurrence of at least one of these six adverse outcomes and is thereby a dichotomous variable with the value 0 or 1.29

Type of economic evaluation, study perspective and time horizon

The economic evaluation took the form of a cost-effectiveness analysis in which we estimated the costs and health outcomes for a planned birth in a birth centre, in a hospital or at home. The economic evaluation was performed from a healthcare perspective. The time horizon of the economic evaluation was from the start of labour until 7 days after birth (end of maternity care period). Because of this short time frame no discounting took place. Costs were in 2015 €; cost prices from earlier years were converted to 2015 € using the consumer price index.34

Measurement of resource use

Volume of healthcare resource use was collected prospectively by the attending community midwives using a case record form which was designed to complement the data from the Netherlands Perinatal Registry.3 The case record form included additional process indicators and volumes such as the time of the first physical contact between the client and the community midwife after a call at the start of labour, the planned place of birth at the start of labour, time of arrival at the birth centre or hospital, referral to the hospital, use of pain relief, use of transport during referral and maternity care assistance. Information on health outcomes and the use of other medications then pain relief was extracted from the Netherlands Perinatal Registry.

Unit cost estimation

All birth centres (n=23) were asked to send their financial details, including overheads, materials and staff costs, and 16 birth centres sent usable information. These total costs were divided by the total number of births and the total number of postpartum days to calculate unit costs.35 Dutch reference prices were used for consultation costs, blood transfusion and ambulance transport.36 37 These reference prices include personnel costs, material costs, costs of medical equipment and supporting departments, accommodation and overhead costs. For additional costs of interventions after referral and interventions in the third stage (delivery of the placenta), unit costs estimates were obtained from the Dutch Healthcare Authority (NZA).38 These costs are based on the unit cost of an intervention in a representative selection of Dutch hospitals, weighted by the number of this particular intervention performed in the different hospitals. Unit costs of a birth at a hospital and maternity care assistance were also obtained from the NZA.39 Twenty community midwives were asked about the duration of home-visits between the start of labour and birth and the duration of consultations during and after birth by a gynaecologist and paediatrician. Their mean estimates (respectively 50, 15 and 12 min) were converted into cost prices of consultation using gross salaries. The duration of postpartum consultations by a community midwife and the gross salaries of community midwives were provided by the Royal Dutch Organisation of Midwives (KNOV),40 41 and Dutch reference prices were used for the gross salaries of gynaecologists and paediatricians. Admission costs were based on a Dutch obstetric study.42 Medication costs were obtained from the website of the National Healthcare Institute, which calculates costs for the Dutch situation based on doses and amounts of drugs.43 The cost of medication—which included the drugs and the materials and/or equipment needed for their administration—was based on other studies.44–46 The values obtained as described above were used for the base case analysis (the model with the values that are assumed most likely). Additionally, sensitivity analyses were undertaken on variables with a great diversity in cost prices across the sources, including: epidural, general anaesthesia, birth at hospital with referral, additional costs after referral (spontaneous birth, vacuum extraction, forceps extraction and caesarean section), repair of perineal tear in operating theatre and manual placenta removal. By repeating our analysis with different cost estimates for variables with a great diversity in cost prices among sources, the implications of uncertainty in costs were explored. These sensitivity analyses included an analysis in which the maximum cost found in literature was used and a bottom-up calculation (assigning a value to each of the resources used during an intervention and summing these values) based on resource use estimates of five hospitals (two teaching hospitals and three general hospitals), see table 1.

Table 1.

Unit cost (2015, €) in base case analysis, and sensitivity analysis using maximum cost prices and cost prices resulting from bottom-up calculation

| Unit | Base case analysis | Sensitivity analysis | |||

| Maximum cost in literature | Bottom-up calculation | ||||

| Consultation and medication during first and second stage | Home visit by a midwife | Visit | 4957 | ||

| Gynaecological consultation | Visit | 2037 | |||

| Oxytocin | Dose | 0.6043 | |||

| Epidural | Procedure | 18544 | 52638 | 252 | |

| Remifentanil | Procedure | 8646 | |||

| Morphine | Procedure | 0.6043 | |||

| Pethidine | Procedure | 0.6243 | |||

| Nalbuphine | Procedure | 3.2543 | |||

| Nitrous oxide | Procedure | 42245 | |||

| General anaesthesia | Procedure | 39139 | 71339 | 713 | |

| Cardiotocography | Procedure | 15138 | |||

| Birth (staffing, overhead and referral) and intervention during second stage | Birth at birth centre | Procedure | 980 | ||

| Birth at birth centre with referral | Procedure | 725 | |||

| Birth at home | Procedure | 60457 | |||

| Birth at home with referral | Procedure | 59857 | |||

| Birth at hospital | Procedure | 113639 | |||

| Birth at hospital with referral | Procedure | 113039 | 113039 | 916 | |

| Additional costs after referral | |||||

| Spontaneous birth | Procedure | 67738 | 122342 | 209 | |

| Vacuum extraction | Procedure | 63738 | 144558 | 418 | |

| Forceps extraction | Procedure | 63738 | 144558 | 516 | |

| Caesarean section | Procedure | 86838 | 215758 | 1403 | |

| Intervention and consultation during third stage | Blood transfusion | Procedure | 44637 | 578 | 578 |

| Oxytocin | Dose | 0.6043 | |||

| Repair perineal tear | Procedure | 1543 | |||

| Repair perineal tear in operating theatre | Procedure | 67838 | 1057 | 957 | |

| Manual removal of placenta | Procedure | 74638 | 74638 | 1059 | |

| Paediatric consultation | Visit | 1637 | |||

| Gynaecological consultation | Visit | 2037 | |||

| Admission and transport | Admission mother and child | ||||

| Hospital stay—ward | Day | 39842 | |||

| Hospital stay—medium care | Day | 60542 | |||

| NICU stay | Day | 167942 | |||

| Ambulance transport—urgent | Procedure | 55937 | |||

| Ambulance transport—non-urgent | Procedure | 27037 | |||

| Postnatal care | Postpartum consultation by a midwife | Visit | 3357 | ||

| Birth centre stay | Day | 372 | |||

| Maternity care assistance | Hour | 4539 | |||

| Maternity care assistance | Once | 8439 | |||

Analytical methods

Total costs per birth were calculated after multiplying resource use per woman and unit costs.

A decision rule was used for missing values that were needed to calculate the outcome scores (OI and CAO): not registered was considered as not happened (since some items did not need to be filled in). Multiple imputation (20 datasets) was used to correct for other missing data. Missing values that were imputed for the cost analysis were: ambulance use (missing 0.2%), place of admission of the child (missing 1.7%), duration of admission of the child (missing 11.0%), duration of postpartum stay at the birth centre (missing 3.7%) and maternity care assistance during birth (missing 5.0%). The variables of the OI, age, parity and maternal background were used as predictors. An iterative Markov chain Monte Carlo method was used in which, for each iteration and for each variable, the fully conditional specification method is in keeping with a univariate model using the other variables as predictors; this then imputes missing values for the relevant variable. Rubin's rules were used for combining the 20 imputed datasets.47

We estimated differences in costs using the one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Although the cost data were skewed, the arithmetic mean is the informative measure for cost data in cost-effective analysis. Analyses other than the arithmetic mean can produce misleading conclusions. Therefore, ANOVA is appropriate for costs where untransformed data are concerned.48 49 Multiple regression was used to estimate the differences in total cost and to adjust for potential confounders including parity (nulliparous/multiparous), mean maternal age, maternal background (Dutch/non-Dutch), urbanisation and socioeconomic status (SES). Urbanisation (<500 addresses per km²/500 to <1500 addresses per km²/≥1500 addresses per km²) and SES (high/medium/low) were based on the characteristics of the four-digit postal code area in which the participants live (level of income, educational level, labour market situation).50

Non-parametric bootstrapping was used, involving 1000 replications, to calculate uncertainty around all cost and health outcomes estimates. The net benefit regression framework was used to construct the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC) comparing a planned birth in a hospital or at home with a planned birth in a birth centre.51 Net benefit regression uses net benefit, defined as nb= λ·effect–cost for each individual patient as dependent variable, where λ is the maximum willingness to pay for a point improvement on the OI. Using the regression equation, nb=α+β BC+γ X+ε with BC the indicator variable for a planned birth in a birth centre, for example, BC=1 if the planned birth was in a birth centre and BC=0 if the planned place of birth was in a hospital or at home respectively, and X the potentially confounding variable (parity, maternal age, maternal background, urbanisation and SES) results in estimation of β and its p value, with the latter being used to construct the CEAC. The CEAC for comparing the different types of birth centres was based on bootstrapping the adjusted costs and health outcomes and plotting the proportion of births with the highest net benefit for the different types of birth centres (with respect to location and integration profile) for a range of values relating to the willingness to pay for a point improvement on the OI.

Since it is known that parity highly influences the progress and outcomes of childbirth,52 all analyses were repeated by parity subgroup (nulliparous vs multiparous women). Analyses were performed using SPSS V.21 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Seattle, Washington, USA) 2010 software.

Results

Health outcomes

The characteristics of the participating women and the analyses of the health outcomes are reported in detail elsewhere.22 Overall, no differences on the OI were found in the cohort study between a planned birth in a birth centre (nulliparous OI=25.8 and multiparous OI=28.1) and a planned birth in a hospital (nulliparous OI=26.0 and multiparous OI=28.0). Women who planned to give birth at home had better outcomes (higher score on the

OI) on the OI (nulliparous OI=26.3 and multiparous OI=28.8) compared with a planned birth in a birth centre; the effect size is small for nulliparous and medium for multiparous. Within the three types of birth centres based on location only the OI score of nulliparous women with a planned birth in a freestanding birth centre (27.4) was better (p<0.001) compared with a planned birth in an alongside birth centre (OI=25.7). No statistical differences in the OI were found for the three different integration profiles, either for nulliparous (MOBC OI=25.7, MIBC OI=25.7 and MUBC OI=26.0) or for multiparous women (MOBC OI=27.9, MIBC OI=28.0 and MUBC OI=28.5).

Overall, an adverse perinatal outcome was rare. No differences were found in the total number of women with one or more adverse outcomes (CAO) between planned births in a birth centre, in a hospital or at home.22

Unadjusted costs in categories

The total unadjusted mean costs per low-risk woman for births planned in a birth centre (€3361) are almost the same as those in a hospital (€3354) and significantly (p<0.001) higher than those at home (€2942). The significant difference in total costs between a planned birth in a birth centre and a planned birth at home is mainly due to: 1) the fact that more women with a planned birth in a birth centre received an epidural and a cardiotocography, 2) the higher overhead costs of the birth centre itself and 3) more mothers and children with a planned birth in a birth centre being admitted to a clinical ward. With regard to the different types of birth centres (based on location and integration profile), there were no differences in unadjusted mean costs, see table 2.

Table 2.

Unadjusted mean (SD) costs (2015, €) in categories per woman according to planned place of birth

| Planned place of birth | Consultation and medication during first and second stage† | Birth and intervention during second stage‡ | Intervention and consultation during third stage§ | Admission and transport¶ | Postnatal care†† | Total |

| Birth centre (n=1668) Ref | 155 (140) | 1074 (321) | 55 (179) | 254 (858) | 1823 (311) | 3361 (1015) |

| Hospital‡‡ (n=701) | 148 (134) | 1015 (327)*** | 39 (145)** | 288 (1013) | 1863 (269)** | 3354 (1143) |

| Home (n=1086) | 105 (106)*** | 696 (286)*** | 43 (157) | 201 (845)** | 1898 (215)*** | 2942 (892)*** |

| Birth centre—location | ||||||

| Freestanding (n=65) | 98 (109)*** | 1280 (260)*** | 32 (116) | 193 (558) | 1884 (288) | 3487 (641) |

| Alongside (n=1202) Ref | 163 (143) | 1061 (307) | 51 (172) | 260 (860) | 1827 (304) | 3362 (976) |

| On-site (n=401) | 141 (132)** | 1078 (358) | 71 (205) | 245 (947) | 1804 (331) | 3338 (1164) |

| Birth centre—integration profile | ||||||

| MOBC (n=923) | 163 (136) | 1112 (290) | 48 (162) | 231 (770) | 1841 (289) | 3394 (867) |

| MIBC (n=349) | 147 (138) | 961 (332)*** | 70 (220) | 327 (1046) | 1763 (348)** | 3268 (1225) |

| MUBC (n=396) Ref | 144 (149) | 1085 (356) | 57 (176) | 244 (929) | 1835 (318) | 3366 (1118) |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

†Consultation and medication includes: home visit by a midwife, gynaecological consultation, pain relief and cardiotocography during first and second stage.

‡Birth and intervention includes: community midwife, maternity care assistance, overhead costs and additional costs after referral during second stage.

§Intervention and consultation includes: blood transfusion, oxytocin, repair perineal tear, manual removal of placenta, consultation by paediatrician/gynaecologist during third stage.

¶Admission and transport includes: admission mother and/or child to hospital and ambulance transport.

††Postnatal care includes: consultation by a midwife, birth centre stay, maternity care assistance.

‡‡Community midwife led.

MIBC, mixed group of birth centre; MOBC, monodisciplinary-oriented birth centre; MUBC, multidisciplinary-oriented birth centre.

Adjusted total costs

The general linear model on costs showed that, after adjustment for confounders, the costs of a planned birth in a birth centre (€3327) remained the same as in a hospital (€3330) and were significantly (p<0.001) higher than a planned birth at home (€2998). With regard to the different types of birth centres (based on location and integration profile), the adjusted mean costs did not vary significantly either.

Restriction of the analyses to nulliparous women showed overall higher mean costs per woman. The costs of a planned birth in a birth centre (€3653) and at home (€3397) differed significantly (p<0.001). With regard to the different types of birth centres (based on location and integration profile), there were no differences in adjusted mean costs.

Restriction of the analyses to multiparous women showed overall lower mean costs per woman and significantly (p<0.001) lower costs for women with a planned place of birth at home (€2639), compared with a birth planned in a birth centre (€3018). The adjusted mean costs of a planned birth in a freestanding birth centre (€3278) were significantly (p<0.05) higher than in an alongside birth centre (€3003). The adjusted mean costs of a planned birth in a birth centre in MIBC (€2839) were significantly (p<0.01) lower than MUBC (€3098), see table 3.

Table 3.

(Adjusted) mean (SD) of total costs (2015, €) per woman according to planned place of birth

| Total costs | Total costs | |||||

| n | Mean (SD) | B (95% CI) | n | Mean (SD) | B (95% CI) | |

| All low-risk women | Unadjusted | Adjusted† | ||||

| Birth centre | 1668 | 3361 (1015) | Ref | 1610 | 3327 (6194) | Ref |

| Hospital‡ | 701 | 3354 (1143) | −7.4 (−99.4 to 84.6) | 659 | 3330 (1158) | 3.9 (−84.5 to 92.3) |

| Home | 1086 | 2942 (892) | −418.8 (−501.0 to 336.7)*** | 1067 | 2998 (1414) | −328.6 (−413.6 to 243.7)*** |

| Birth centre—location | ||||||

| Freestanding | 65 | 3487 (641) | 124.6 (−139.3 to 388.5) | 65 | 3469 (1026) | 162.7 (−86.8 to 412.2) |

| Alongside | 1202 | 3362 (976) | Ref | 1158 | 3306 (5215) | Ref |

| On-site | 401 | 3338 (1164) | −23.6 (−142.7 to 95.6) | 387 | 3364 (1142) | 57.6 (−56.1 to 171.4) |

| Birth centre—integration profile | ||||||

| MOBC | 923 | 3394 (867) | 28.5 (−94.4 to 151.3) | 889 | 3342 (1783) | −14.8 (−132.0 to 102.5) |

| MIBC | 349 | 3268 (1225) | −97.6 (−250.9 to 55.8) | 338 | 3250 (1377) | −107.3 (−254.2 to 39.6) |

| MUBC | 396 | 3366 (1118) | Ref | 383 | 3357 (3094) | Ref |

| Nulliparous | Unadjusted | Adjusted§ | ||||

| Birth centre | 939 | 3655 (1114) | Ref | 913 | 3653 (7276) | Ref |

| Hospital‡ | 348 | 3644 (1356) | −11.5 (−160.3 to 137.3) | 328 | 3607 (1397) | −45.8 (−196.9 to 105.4) |

| Home | 399 | 3390 (1084) | −265.7 (−415.6 to 115.9)*** | 392 | 3397 (1584) | −255.6 (−412.7 to 98.5)*** |

| Birth centre—location | ||||||

| Freestanding | 33 | 3691 (673) | 56.1 (−361.7 to 474.0) | 33 | 3680 (1262) | 51.2 (−379.8 to 482.2) |

| Alongside | 699 | 3635 (1061) | Ref | 680 | 3629 (6317) | Ref |

| On-site | 207 | 3720 (1319) | 84.7 (−97.0 to 266.5) | 200 | 3730 (1378) | 100.8 (−90.2 to 291.9) |

| Birth centre—integration profile | ||||||

| MOBC | 522 | 3666 (954) | 19.9 (−162.9 to 202.7) | 507 | 3657 (2199) | 10.8 (−180.6 to 202.2) |

| MIBC | 198 | 3636 (1243) | −10.4 (−238.0 to 217.1) | 193 | 3649 (1694) | 3.4 (−235.8 to 242.6) |

| MUBC | 219 | 3647 (1319) | Ref | 213 | 3646 (3664) | Ref |

| Multiparous | Unadjusted | Adjust§ | ||||

| Birth centre | 729 | 2982 (709) | Ref | 697 | 3018 (3977) | Ref |

| Hospital‡ | 353 | 3068 (788) | 85.6 (−6.3 to 177.5) | 331 | 3074 (860) | 56.2 (−36.4 to 148.9) |

| Home | 687 | 2683 (623) | −299.7 (−374.0 to 225.4)*** | 675 | 2638 (1040) | −379.5 (−457.9 to 301.1)*** |

| Birth centre—location | ||||||

| Freestanding | 32 | 3276 (526) | 293.0 (37.8 to 548.3)* | 32 | 3278 (726) | 275.8 (24.2 to 527.5) |

| Alongside | 503 | 2983 (681) | Ref | 478 | 3003 (3323) | Ref |

| On-site | 194 | 2932 (792) | −51.0 (−171.0 to 69.0) | 187 | 3012 (838) | 9.3 (−110.8 to 129.4) |

| Birth centre—integration profile | ||||||

| MOBC | 401 | 3040 (565) | 21.6 (−107.8 to 151.0) | 382 | 3049 (1302) | −48.5 (−179.1 to 82.0) |

| MIBC | 151 | 2786 (1017) | −232.6 (−388.4 to 76.8)** | 145 | 2839 (955) | −259.2 (−414.7 to 103.7)** |

| MUBC | 177 | 3019 (654) | Ref | 170 | 3098 (2082) | Ref |

Mean costs and health outcomes (OI).

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

†Adjusted for parity, maternal age, maternal background, urbanisation and social economic status.

‡Community midwife led.

§Adjusted for maternal age, maternal background, urbanisation and social economic status.

MIBC, mixed group of birth centre; MOBC, monodisciplinary-oriented birth centre; MUBC, multidisciplinary-oriented birth centre.

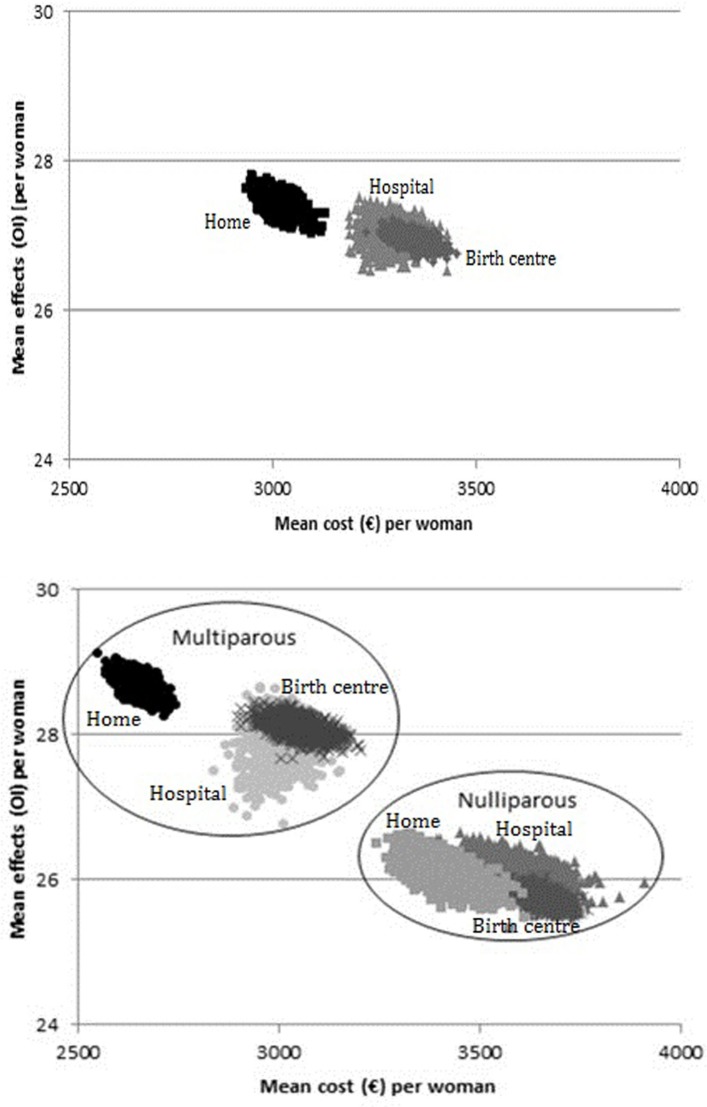

Uncertainty around costs and health outcomes (OI) obtained by bootstrapping are plotted in figure 1A (total group) and figure 1B (nulliparous and multiparous women).

Figure 1A and B.

Mean cost (2015, €) and health outcomes (Optimality Index) of planned birth at a birth centre, hospital and at home under the supervision of a community midwife.

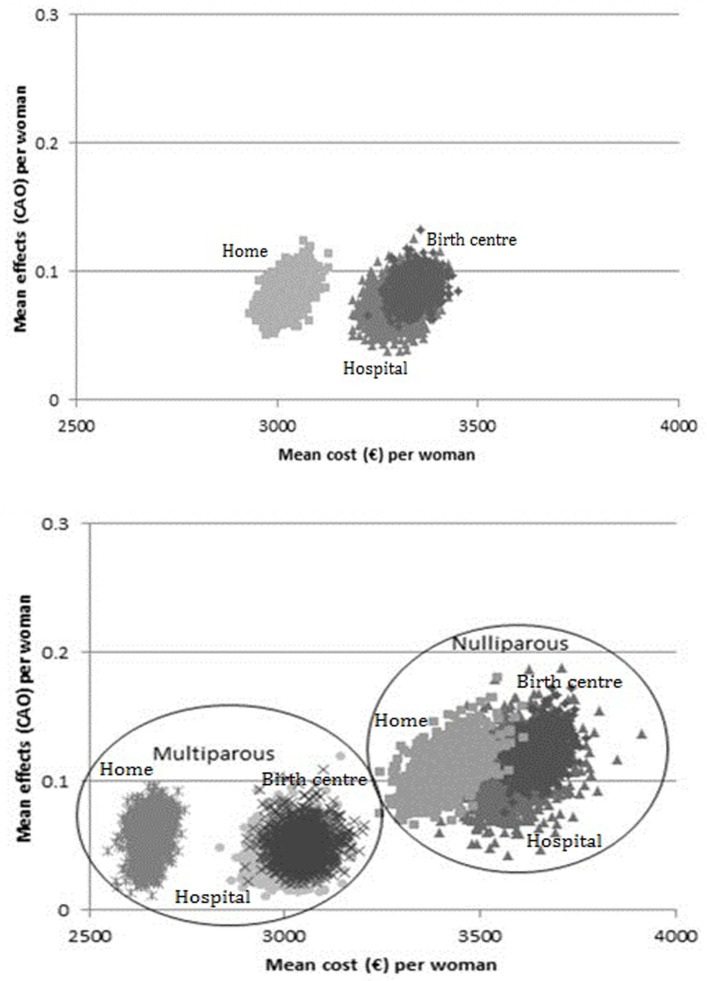

Mean costs and health outcomes (CAO)

The total adjusted adverse outcomes (CAO) and the adjusted total mean costs per woman were similar for women with a planned birth in a birth centre and in a hospital. The CAO was also similar for women with a planned birth in a birth centre and at home, but a planned birth at home resulted in lower costs, see figure 2A. With regard to the parity subgroups, multiparous women had more favourable health outcomes and lower adjusted total mean costs than nulliparous women, see figure 2B.

Figure 2A and B.

Mean cost (2015, €) and health outcomes (composite adverse outcome score) of planned birth at a birth centre, hospital and at home under the supervision of a community midwife.

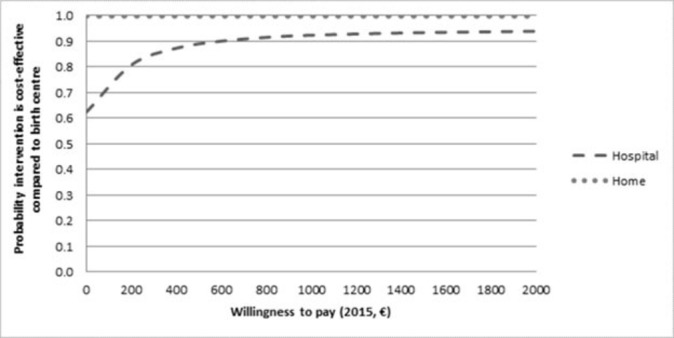

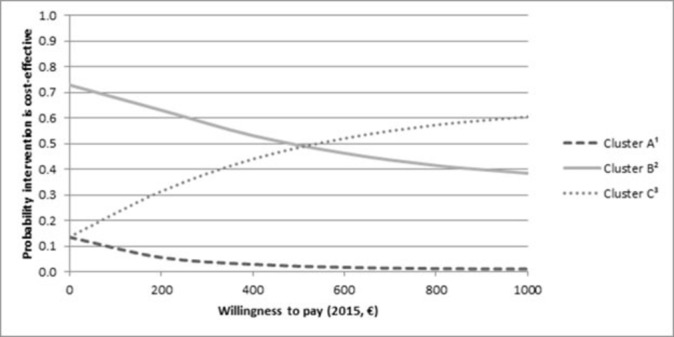

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves

Figure 3 shows the probability that a planned birth in a hospital or at home is cost-effective, compared with a planned birth in a birth centre, for different willingness-to-pay values (€0–€2000) for an improvement of one point on the OI. Regardless of the level of willingness to pay, a planned birth at home was likely to be cost-effective compared with a planned birth in a birth centre. A planned birth at home had more favourable health outcomes (higher score on the OI) and lower costs compared with a planned birth in a birth centre. The probability that a birth planned in a hospital is cost-effective increased with a higher willingness to pay, compared with a planned birth in a birth centre. A planned birth in a hospital had more favourable health outcomes (higher score on the OI) but also higher costs compared with a planned birth in a birth centre.

Figure 3.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, graphing the probability to be cost-effective for planned birth at the hospital and at home compared with the birth centre, for different values of the willingness to pay for an additional point on the Optimality Index.

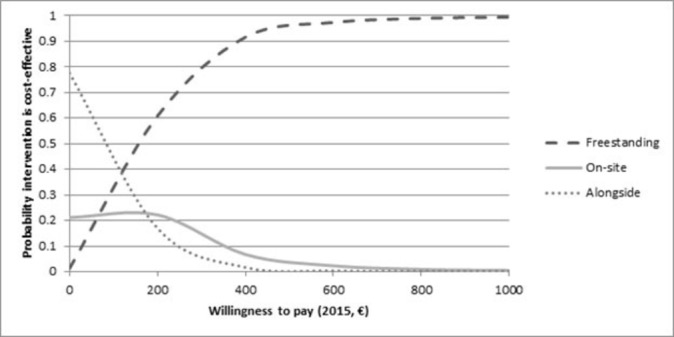

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves—type of birth centre based on location

Figure 4 shows the probability that a planned birth in a particular type of birth centre based on location is cost-effective, compared with a planned birth in the two other location types, for different willingness-to-pay values (€0–€1000). If the willingness to pay for an extra point on the OI (health benefits) is €0, the probability that a planned birth in an alongside birth centre is cost-effective is highest. The higher the willingness to pay, the higher the probability that a planned birth in a freestanding birth centre is cost-effective, compared with the two other types (alongside and on-site). A planned birth in a freestanding birth centre had more favourable health outcomes (higher score on the OI), but higher costs, compared with the two other types.

Figure 4.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, graphing the probability to be cost-effective for planned birth in a freestanding, alongside and on-site birth centre, for different values of the willingness to pay for an additional point on the Optimality Index.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves—integration profile of birth centre

Figure 5 shows the probability that a planned birth in a particular type of birth centre based on integration profiles is cost-effective, compared with a planned birth in the two other location types, for different willingness-to pay-values (€0–€1000). If the willingness to pay for an extra point on the OI (health benefits) is €0, the probability that a planned birth in a MIBC is cost-effective is highest. The higher the willingness to pay, the higher the probability that a planned birth in an MUBC is cost-effective, compared with the two other types (MOBC and MIBC). A planned birth in an MUBC has more favourable health outcomes (higher score on the OI), but higher costs, compared with the two other types.

Figure 5.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves, graphing the probability to be cost-effective for planned birth in a monodisciplinary-oriented birth centre, mixed group of birth centre and multidisciplinary-oriented birth centre, for different values of the willingness to pay for an additional point on the Optimality Index.

Adjusted total mean costs with varying costs prices

Finally, sensitivity analyses produced similar results as the original generalised linear model on costs: no cost differences between planned birth in a birth centre and in a hospital; planned birth at home had significantly (p<0.001) lower costs than planned birth in a birth centre and no cost differences between the different types (based on location and integration profiles) of birth centres, see table 4.

Table 4.

Adjusted mean (SD) of total cost (2015, €) per woman according to planned place of birth in sensitivity analyses using maximum cost prices and cost prices resulting from a bottom-up calculation with five hospitals

| Maximum cost | Bottom-up calculation | |||

| Adjusted* | Adjusted* | |||

| All low-risk women | Mean (SD) | B (95% CI) | Mean (SD) | B (95% CI) |

| Birth centre (n=1610) | 3696 (7601) | Ref | 3206 (6103) | Ref |

| Hospital† (n=659) | 3643 (1456) | −53.5 (−164.7 to 57.7) | 3182 (1157) | −24.3 (−112.6 to 64.1) |

| Home (n=1067) | 3271 (1742) | −425.4 (−530.0 to 320.8)*** | 2919 (1413) | −287.1 (−372.0 to 202.2)*** |

| Birth centre—location | ||||

| Freestanding (n=65) | 3638 (1281) | −50.5 (−362.0 to 261.0) | 3397 (1025) | 219.4 (−29.9 to 468.7) |

| Alongside (n=1158) | 3689 (6490) | Ref | 3178 (5211) | Ref |

| On-site (n=387) | 3729 (1433) | 39.9 (−102.9 to 182.7) | 3260 (1141) | 82.4 (−31.3 to 196.1) |

| Birth centre—integration profile | ||||

| MOBC (n=889) | 3730 (2246) | 36.0 (−111.7 to 183.7) | 3201 (1783) | −54.9 (−172.1 to 62.4) |

| MIBC (n=338) | 3604 (1712) | −89.9 (−272.4 to 92.7) | 3165 (1376) | −90.3 (−237.1 to 56.5) |

| MUBC (n=383) | 3694 (3866) | Ref | 3256 (3093) | Ref |

*Adjusted for parity, maternal age, maternal background, urbanisation and social economic status.

†Community midwife led.

***p<0.001.

MIBC, mixed group of birth centre; MOBC, monodisciplinary-oriented birth centre; MUBC, multidisciplinary-oriented birth centre.

Discussion

Summary of main findings

No differences were found in costs for birth if planned either in a birth centre or in a hospital. The costs of a planned birth at home are significantly lower compared with a planned birth at a birth centre. The total adjusted mean costs for births planned in a birth centre, in a hospital and at home were €3327, €3330 and €2998, respectively. There was no difference in the score on the OI for women who planned to give birth in a birth centre compared with women who planned to give birth in a hospital. Women who planned to give birth at home had better outcomes on the OI (higher score on the OI). No differences were found for the CAO score by planned place of birth. For nulliparous and multiparous low-risk women, a planned birth at home was the most cost-effective option compared with a planned birth in a birth centre.

No differences were found in the total adjusted mean costs for planned births for the different types of birth centres (based on location and integration profiles). The respective total adjusted mean costs for a birth planned in a freestanding, alongside and on-site birth centre were €3469, €3306 and €3364, respectively. The respective total adjusted mean costs for births planned at a birth centre were €3342, €3250 and €3,357, when divided by the integration profile a) monodisciplinary-oriented, b) mixed group of birth centres and c) multidisciplinary-oriented). Within the three types of birth centres based on location, the OI score for nulliparous women with a planned birth in a freestanding birth centre was significantly higher compared with a planned birth in an alongside birth centre. No big differences on the OI were found for the three different integration profiles. The CAO of nulliparous women with a planned birth in an MIBC was significantly more unfavourable than a planned birth in an MUBC.

Strengths and weaknesses

This study is an initial attempt to expand the net benefit regression framework from two to three treatments. In the literature on cost-effectiveness analyses, only two treatments have to date been compared using the net benefit regression approach. This study has a high participation rate as regard to midwifery practices (110 of the 127 approached) and birth centres (21 out of 23), which reduces the chance of bias. Sensitivity analyses, using different prices, produced similar results and conclusions to those of the original generalised linear model on costs, in other words, the impact of systematic errors (bias) was low.

The limited time horizon of the study meant that the registration of outcomes for mother and child did not extend beyond 1 week post partum. Perinatal events (such as a low Apgar score) can result in associated long-term costs, which are not covered in this study. As serious perinatal events were rare in this low-risk group, this would not have changed the results.22 As usual in economic evaluations, we had to deal with missing data. However, the magnitude of missing data was limited and multiple imputation (20 datasets) was used to impute the missing data.

A problem of all (Dutch) studies comparing places of birth is that women in these places are all different. Although this is taken into account in the statistical analyses by adjusting for SES, maternal background, parity, age and urbanisation, it is not possible to adjust completely. For example, women who planned to give birth in a birth centre or hospital may have a different view on childbirth and are perhaps more anxious than women who planned to give birth at home.53–56 In addition, there may be differences between the groups as regard to lifestyle, such as smoking, and obstetric history, including the number of miscarriages. Therefore, the minor differences found in this study may be the result of differences between the women rather than between the settings.

Interpretation of the results

This study is part of the Dutch Birth Centre study.30 The motive for this national study was the strong increase in the number of birth centres in the Netherlands over the last few decades and the unknown effect on outcomes such as costs, medical outcomes and client experiences.

We found comparable costs for a planned birth supervised by a community midwife in a birth centre and in a hospital and significantly lower costs for a planned birth at home. Another Dutch study found that the total costs associated with pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum care are comparable for home birth and hospital birth. That study found lower costs during childbirth and postpartum care for maternity care assistance, admission and travelling costs for the home birth group compared with the hospital group.14 Our study showed lower costs for maternity care assistance for the birth centre group compared with the hospital and home birth group. In line with that study, the admission and transport costs were lower for the home birth group. The other study was based on actual births and not, as in our study, on planned place of birth (intention to treat) and did not include the birth centre setting . We did not include pregnancy costs since this is not part of birth centre care in the Netherlands. Our results are in line with a study in England where a planned birth at home is cost-effective compared with a planned birth in alongside or freestanding midwifery units and obstetric units. However, we did not find increased adverse perinatal outcomes for nulliparous women planning to give birth at home.15

One of the aims of this study is to provide objective, reliable and valid information to support decision making and policy making in healthcare. As most low-risk women in the Netherlands are now planning to give birth outside their home, it is necessary to offer these women a good alternative. Birth centres offer a more home-like environment and are based on the philosophy of physiological birth. To know whether birth centres are a good alternative, policy makers, health insurers and managers want information on the cost-effectiveness of birth centres versus alternative places of birth. We conclude that for nulliparous and multiparous low-risk women, a planned birth at home was the most cost-effective option compared with a planned birth in a birth centre. Planned births in birth centres have similar health outcomes and costs as hospital births for low-risk women.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MiH, MaH, IB, KPB and EAM were involved in planning, recruitment of midwifery practices and conduction of the study. MiH, MaH, IB and EAM drafted the manuscript. MH and EAM analysed the data. All the authors listed are members of the ‘Dutch Birth Centre study group’ and discussed the progress, results and implications. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Informed consent is given by approval of participation to the Dutch National Perinatal Registry.

Ethics approval: The Medical Ethics Committee at the University of Utrecht (The Netherlands)

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.College voor zorgverzekeringen. Verloskundig vademecum 2003. diemen: college voor zorgverzekeringen. Diemen 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.KNOV. Midwifery in the Netherlands, 2016. (accessed 12 May 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Netherlands perinatal registry. Perinatal care in the Netherlands 2013. Utrecht: Perinatale zorg in Netherland 2013, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hermus MA, Wiegers TA, Hitzert MF, et al. . The DutchBirth Centre study: study design of a programmatic evaluation of the effect of birth centre care in the Netherlands. BMC pregnancy childbirth 2015;15:148. 10.1186/s12884-015-0585-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rooks JP, Weatherby NL, Ernst EK. The National Birth Center Study. part I-methodology and prenatal care and referrals. J Nurse Midwifery 1992;37:222–53. 10.1016/0091-2182(92)90128-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laws PJ, Lim C, Tracy S, et al. . Characteristics and practices of birth centres in Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Hynaecol 2009;49:290–5. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2009.01002.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Vries R, Wiegers TA, Smulders B, et al. . The dutch obstetrical system. Birth models that work 2009;31. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson TR, Callister LC, Freeborn DS, et al. . Dutch women's perceptions of childbirth in the Netherlands. MCN AM J Matern Child Nurs 2007;32:170–7. 10.1097/01.NMC.0000269567.09809.b5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner M. Born in the USA: How a broken maternity system must be fixed to put women and children first. Berkeley:University of california press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mander R. The relevance of the Dutch system of maternity care to the UK. J Adv Nurs 1995;22:1023–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1995.tb03100.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oppenheimer C. Organising midwifery led care in the Netherlands. BMJ 1993;307:1400–2. 10.1136/bmj.307.6916.1400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohangoo AD, Buitendijk SE, Hukkelhoven CW, et al. . [Higher perinatal mortality in the Netherlands than in other European countries: the Peristat-II study]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2008;152:2718–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonsel GJ, Birnie E, Denktas S, et al. . Dutch report:lines in the perinatal mortality, signalement study of pregnancy and birth in. Rotterdam: Erasmus MC, 20102010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hendrix MJ, Evers SM, Basten MC, et al. . Cost analysis of the Dutch obstetric system: low-risk nulliparous women preferring home or short-stay hospital birth--a prospective non-randomised controlled study. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:211. 10.1186/1472-6963-9-211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schroeder E, Petrou S, Patel N, et al. . Cost effectiveness of alternative planned places of birth in woman at low risk of complications: evidence from the birthplace in england national prospective cohort study. BMJ 2012;344:e2292. 10.1136/bmj.e2292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone PW, Zwanziger J, Hinton Walker P, et al. . Economic analysis of two models of low-risk maternity care: a freestanding birth center compared to traditional care. Res Nurs Health 2000;23:279–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hundley VA, Donaldson C, Lang GD, et al. . Costs of intrapartum care in a midwife-managed delivery unit and a consultant-led labour ward. Midwifery 1995;11:103–9. 10.1016/0266-6138(95)90024-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson J, Petrou S. Economic implications of home births and birth centers: a structured review. Birth 2008;35:136–46. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2008.00227.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spitzer MC. Birth centers. Economy, safety, and empowerment. J Nurse Midwifery 1995;40:371–5. 10.1016/0091-2182(95)00033-G [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janssen PA, Mitton C, Aghajanian J. Costs home vs. hospital birth in British Columbia attended by registered midwives and physicians. PLoS One 2015;10:e0133524 10.1371/journal.pone.0133524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tracy SK, Welsh A, Hall B, et al. . Caseload midwifery compared to standard or private obstetric care for first time mothers in a public teaching hospital in australia: a cross sectional study of cost and birth outcomes. BMC pregnancy childbirth 2014;14:46. 10.1186/1471-2393-14-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hermus MAA, Hitzert M, Boesveld IC, et al. . Differences in optimality index between planned place of birth in a birth centre and alternative planned places of birth, a nationwide prospective cohort study in the Netherlands, submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Hollis S, Campbell F. What is meant by intention to treat analysis? survey of published randomised controlled trials. BMJ 1999;319:670–4. 10.1136/bmj.319.7211.670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hermus MAA, Boesveld IC, Hitzert M, et al. . Defining and describing birth centres in the Netherlands - a component study of the Dutch Birth Centre Study. BMC pregnancy childbirth. In Press 2017;17:210. 10.1186/s12884-017-1375-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valentijn PP, Boesveld IC, van der Klauw DM, et al. . Towards a taxonomy for integrated care: a mixed-methods study. Int J Integr Care 2015;15 10.5334/ijic.1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kodner DL. All together now: a conceptual exploration of integrated care. Healthc Q 2009;13:6–15. 10.12927/hcq.2009.21091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goodwin N, Peck E, Freeman T, et al. . Managing across diverse networks of care: lessons from other sectors Report to the NHS SDO R&D programme birmingham: health services management centre, university of birmingham, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boesveld IC, Bruijnzeels MA, Hitzert M, et al. . Typology of birth centres in the netherlands using the rainbow model of integrated care: results of the Dutch Birth Centre study. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:426. 10.1186/s12913-017-2350-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hermus MAA, Boesveld IC, van der Pal-de Bruin KM, et al. . Development of the optimality Index-NL2015, an instrument to measure outcomes of maternity care. Journal of midwifery and women's health 2017. Article in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hermus MA, Wiegers TA, Hitzert MF, et al. . The Dutch Birth Centre study: study design of a programmatic evaluation of the effect of birth centre care in the netherlands. BMC pregnancy childbirth 2015;15:148. 10.1186/s12884-015-0585-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiegers TA, Keirse MJ, Berghs GA, et al. . An approach to measuring quality of midwifery care. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:319–25. 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00549-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy PA, Fullerton JT. Development of the optimality index as a new approach to evaluating outcomes of maternity care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2006;35:770–8. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00105.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy PA, Fullerton JT. Measuring outcomes of midwifery care: development of an instrument to assess optimality. J midwifery womens health 2001;46:274–84. 10.1016/S1526-9523(01)00158-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.StatisticNetherlands. Consumer price index. statline.cbs.nl (accessed April 2015).

- 35.Tan SS, Rutten FF, van Ineveld BM, et al. . Comparing methodologies for the cost estimation of hospital services. Eur J Health Econ 2009;10:39–45. 10.1007/s10198-008-0101-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan SS, Bouwmans CA, Rutten FF, et al. . Update of the Dutch manual for costing in economic evaluations. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2012;28:152–8. 10.1017/S0266462312000062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hakkaart-van R, Tan S, Bouwmans C. Manual for costing research: methods and cost prices for economic evaluation in health care, update 2010 [in dutch]. Diemen: college voor zorgverzekeringen 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 38.The dutch healthcare authority. Dataset cost care activities of the dutch healthcare authority. Utrecht, the Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 39.The dutch healthcare authority. Working with the casemix system (DBC) [in dutch] [website]. The Dutch healthcare authority 2015. http://www.dbconderhoud.nl/zz-releases/rz15b-update-tarieventabel2015. [Google Scholar]

- 40.The Royal Dutch Organization of Midwives (KNOV). Duties in obstetrics. Research on tasks, time-management and production of community midwives [In Dutch] 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.The royal dutch organization of midwives (KNOV). Tariff and cost information [In dutch] 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liem SM, van Baaren GJ, Delemarre FM, et al. . Economic analysis of use of pessary to prevent preterm birth in women with multiple pregnancy (ProTWIN trial). Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2014;44:338–45. 10.1002/uog.13432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.The national health care institute. Medicine costs [in dutch. www.medicijnkosten.nl (accessed March 2015).

- 44.van Baaren GJ, Jozwiak M, Opmeer BC, et al. . Cost-effectiveness of induction of labour at term with a Foley catheter compared to vaginal prostaglandin E 2 gel (PROBAAT trial). BJOG: An Intl J of Obstet Gynecol 2013;120:987–95. 10.1111/1471-0528.12221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.de Graaf JP, Huizer M. Request regular price nitroux oxide at the dutch healthcare Authority and health insurers [in dutch]: geboortecentrum sophia, erasmus MC. Kraamzorg rotterdam. [Google Scholar]

- 46.The RAVEL study group. Remifentanil patient controlled analgesia versus epidural analgesia during labor. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Little R, Rubin D. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. new york: john wiley & sons, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Briggs A, Clark T, Wolstenholme J, et al. . Missingpresumed at random: cost-analysis of incomplete data. Health Econ 2003;12:377–92. 10.1002/hec.766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thompson SG, Barber JA. How should cost data in pragmatic randomised trials be analysed? BMJ 2000;320:1197–200. 10.1136/bmj.320.7243.1197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.The netherlands institute for social research. http://www.scp.nl/english/ (accessed 18 Aug 2015) 2015.

- 51.Hoch JS, Rockx MA, Krahn AD. Using the net benefit regression framework to construct cost-effectiveness acceptability curves: an example using data from a trial of external loop recorders versus holter monitoring for ambulatory monitoring of "community acquired" syncope. BMC Health Serv Res 2006;6:68. 10.1186/1472-6963-6-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bai J, Wong FW, Bauman A, et al. . Parity and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186:274–8. 10.1067/mob.2002.119639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kleiverda G, Steen AM, Andersen I, et al. . Place of delivery in the Netherlands: maternal motives and background variables related to preferences for home or hospital confinement. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1990;36:1–9. 10.1016/0028-2243(90)90043-Z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiegers TA, Van der Zee J, Kerssens JJ, et al. . Home birth or short-stay hospital birth in a low risk population in the Netherlands. Soc Sci Med 1998;46:1505–11. 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00021-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Haaren-Ten Haken T, Hendrix M, Nieuwenhuijze M, et al. . Preferred place of birth: characteristics and motives of low-risk nulliparous women in the netherlands. Midwifery 2012;28:609–18. 10.1016/j.midw.2012.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Der Hulst LA, van Teijlingen ER, Bonsel GJ, et al. . Does a pregnant woman's intended place of birth influence her attitudes toward and occurrence of obstetric interventions? Birth 2004;31:28–33. 10.1111/j.0730-7659.2004.0271.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.The royal dutch organization of midwives (KNOV). Tariff and cost information 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vijgen SM, Westerhuis ME, Opmeer BC, et al. . Cost-effectiveness of cardiotocography plus ST analysis of the fetal electrocardiogram compared with cardiotocography only. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2011;90:772–8. 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01138.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.