Abstract

Introduction

Stroke is the most disabling neurological disorder and often causes spasticity. Transmucosal cannabinoids (tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol (THC:CBD), Sativex) is currently available to treat spasticity-associated symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis. Cannabinoids are being considered useful also in the treatment of pain, nausea and epilepsy, but may bear and increased risk for cardiovascular events. Spasticity is often assessed with subjective and clinical rating scales, which are unable to measure the increased excitability of the monosynaptic reflex, considered the hallmark of spasticity. The neurophysiological assessment of the stretch reflex provides a precise and objective method to measure spasticity. We propose a novel study to understand if Sativex could be useful in reducing spasticity in stroke survivors and investigating tolerability and safety by accurate cardiovascular monitoring.

Methods and analysis

We will recruit 50 patients with spasticity following stroke to take THC:CBD in a double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over study. Spasticity will be assessed with a numeric rating scale for spasticity, the modified Ashworth scale and with the electromyographical recording of the stretch reflex. The cardiovascular risk will be assessed prior to inclusion. Blood pressure, heart rate, number of daily spasms, bladder function, sleep disruption and adverse events will be monitored throughout the study. A mixed-model analysis of variance will be used to compare the stretch reflex amplitude between the time points; semiquantitative measures will be compared using the Mann-Whitney test (THC:CBD vs placebo) and Wilcoxon test (baseline vs treatment).

Ethics and dissemination

The study was registered on the EudraCT database with number 2016-001034-10 and approved by both the Italian Medicines Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco) and local Ethics Committee ‘Comitato Etico Regionale della Liguria’. Data will be made anonymous and uploaded to a open access repository. Results will be disseminated by presentations at national and international conferences and by publication in journals of clinical neuroscience and neurology.

Keywords: THC:CBD, sativex, stretch reflex, spasticity, stroke, cannabinoids

Strengths and limitations of this study.

First study on Sativex to treat poststroke spasticity.

Electromyographical recording of the stretch reflex to precisely measure spasticity.

Assessment of cannabinoids tolerability in stroke survivors.

Limited number of patients in relation to a monocentric pilot study.

Introduction

Stroke is one of the most disabling neurological disease and frequently determines important chronic consequences such as spasticity. Prevalence of poststroke spasticity ranges from 4% to 42.6%, with the prevalence of disabling spasticity ranging from 2% to 13%.1 Treatment of poststroke spasticity is based on rehabilitation, local injection of botulinum toxin (BoNT) in the affected muscles for focal spasticity and/or use of classic oral drugs such as tizanidine, baclofen, thiocolchicoside and benzodiazepines, which are not always effective and have a good number of possible side effects.

The transmucosal administration of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol (THC and CBD at 1:1 ratio oromucosal spray, Sativex) is able to reduce spasticity acting on endocannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2. This novel drug has been licensed after an extensive clinical trial programme2–4 in adult patients with multiple sclerosis who have shown no significant benefit from other antispasmodic drugs. More than 45 000 patient/years of exposure since its approval in more than 15 EU countries support their antispasticity effectiveness and safety profile in this indication.5 Besides improving spasticity, cannabinoids can be beneficial in reducing pain, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; moreover, they contribute to reducing seizures and to lowering eye pressure in glaucoma.6 Cannabinoids can also exert psychological effects by lowering anxiety levels and inducing sedation or euphoria. Marijuana, which is the main source of cannabinoids, is declared illegal in many countries mostly because of the risk of abuse, dependence and withdrawal syndrome, related to the effect of its high amounts of THC. Several reports support an increased ischaemic stroke risk related to relevant abuse of smoked marijuana7–17 as well as synthetic cannabinoids.18–20 Ischaemic stroke following cannabis involves more frequently basal ganglia and cerebellum where CB1 and CB2 receptors show a higher expression.13

The ‘French Association of the Regional Abuse and Dependence Monitoring Centres Working Group on Cannabis Complications’ warns about the increased cardiovascular risk related to the use of herbal cannabis, mostly consisting of acute coronary syndromes and peripheral arteriopathies, potentially leading to life-threatening conditions.21 The detrimental consequences of cannabinoids could be attributed to the increase in heart rate22 as well as arterial spasms also in the context of a reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome,23 but also vasculitis, postural hypotension and cardioembolism.24

On the other side, some studies support a beneficial effect on stroke evolution of cannabinoid receptors stimulation. In fact, cannabinoid-mediated activation of CB1 and CB2 receptors reduces inflammation and neuronal injury in acute ischaemic stroke.25 Activation of CB2 receptors shows protective effects after ischaemic injury26 and inhibits atherosclerotic plaque progression.27 28

To our knowledge, no correlations have been reported between haemorrhagic stroke and cannabinoids intake. In our opinion, the modification of blood pressure is the most important cannabinoid effect that should be taken into account in patients with a previous haemorrhagic stroke or predisposed to intracranial bleeding. Cannabinoids are indeed capable of inducing blood pressure fluctuations in a specific triphasic pattern (low-high-low) potentially harmful if the patient is with bleeding risk.29 Ischaemic disease is not included among THC:CBD oromucosal spray contraindications. However, considering that, to our knowledge, no study has been performed with THC:CBD oromucosal spray on post-stroke spasticity, we believe that a particular caution should be used in stroke patients.

The decision of which method of measure is considered as end point is a major issue in studies involving spasticity. The definition of spasticity provided by Lance is one of the most precise and reliable, focusing on the stretch reflex as the neurophysiological equivalent of spasticity.30 Probably because of technical complexity and required expertise, neurophysiological approaches are rarely adopted. Clinical rating scales such as the modified Ashworth scale (MAS)31 or subjective scores such as the numeric rating scale (NRS) for spasticity are being widely used.32 33 Recent evidence supports the idea that MAS and NRS are indeed useful to quickly rate spasticity in a clinical setting, however NRS provide a very variable and imprecise assessment of many symptoms related to spasticity, but where spasticity itself is probably only a common factor.34 The adoption of stretch reflex as the most appropriate neurophysiological measure of spasticity increases the specificity and reduces the variability of the end point and is particularly suitable for clinical trials.

Our proposal is therefore to assess the efficacy of THC:CBD oromucosal spray in patients with spasticity following stroke as add-on to first-line antispasticity medications with an experimental pilot randomised placebo-controlled cross-over clinical trial using the stretch reflex as primary outcome measure. Prior to inclusion in the study, we propose strict selection criteria in order to reduce the risk of relevant side effects.

Methods and analysis

Subjects

At the Department of Neuroscience of the ‘Ospedale Policlinico San Martino’, we will recruit 50 patients with spasticity secondary to stroke that occurred at least 3 months earlier. Both naïve to BoNT or BoNT-treated patients will be recruited; however, those treated with BoNT will enter the study at least 4 months after the last injection in order to allow a reasonable washout. The study will last 2 years.

Inclusion criteria are:

Presence of spasticity rated between 1 and 3 at the MAS in at least one of the following segments: flexor muscles of the wrist, flexor muscles of the elbow, extensor muscles of the leg and/or foot plantar flexors;

Absence of significant peripheral nervous system pathology detectable on clinical basis;

Absence of concomitant parkinsonism;

Acceptable cardiovascular ischaemic risk following a cardiological evaluation along with the laboratory and instrumental examinations requested by the cardiologist, as well as a CHA2DS2VASc score (currently used to estimate the risk of stroke in patients with non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation) less than 7;

Absence of a demonstrated stenosis higher than 50% at intracranial main arteries (mean cerebral, basilar, internal carotid, vertebral) or at cervical tracts of carotid and vertebral arteries;

Absence of significant cognitive impairment hampering patients’ capability of understanding the study protocol and signing the consent form;

Apart from the criteria listed above, there will be no limitations related to age, sex and degree of disability.

The following sociodemographic data will be collected: gender, age, time of acute lesion, years with spasticity, areas affected with spasticity.

Study protocol

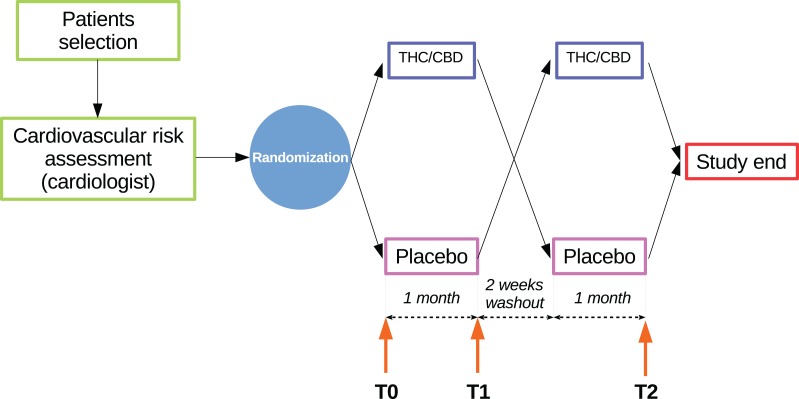

Patients will enter a cross-over study paradigm after a cardiac-cerebral-vascular risk assessment performed by a cardiologist and by a vascular neurologist; those with an acceptable cardiac-cerebral-vascular risk will be randomly assigned (in a 1:1 ratio) to one of the two following treatment sequences (figure 1):

THC:CBD oromucosal spray—placebo (ie, THC:CBD oromucosal spray during period I and placebo during period II)

Placebo—THC:CBD oromucosal spray (ie, placebo during period I and THC:CBD oromucosal spray during period II)

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the study protocol, particularly depicting the cross-over design and the time points. THC/CBD, tetrahydrocannabinol/cannabidiol.

The randomisation list will be generated through a validated SAS programme, in permuted blocks of reasonable size in order to guarantee the treatment balance.

After the first (T0) baseline evaluation visit, during the 1-month period, the patients will titrate their medication to reach the optimal number of puffs/day and then evaluated again (T1). A 2 weeks washout time will allow patients taking THC:CBD oromucosal spray (or placebo) to reach their baseline spasticity condition and then patients will switch arms and perform another month for the other treatment. After a while, the final (T2) assessment will be performed. During the whole study, the patients will have to maintain the same therapy apart from the study drug in order to minimise other conditions that could affect the level of spasticity. For the same reason, patients are required not to undergo any physical and rehabilitative treatment during the study. During T1 and T2 evaluation, additional information about the number of sprays/day will be collected, along with all possible adverse events. During the 10 weeks of the study, patients not responding to the treatment and unable to complete the study untreated will undergo a rescue treatment (eg, BoNT) and exit the study. All patients will be monitored by a neurological clinical follow-up at least for 1 year on study termination.

This is a double-blind study. All individuals involved in the study conduct, including patients, investigator staff, persons performing the assessments and data analysts will remain blinded to the identity of the treatment from the time of randomisation until database lock.

Randomisation data will be kept strictly confidential until the time of unblinding and will not be accessible to anyone involved in the conduct of the study. The identity of the treatments will be concealed by the use of study drugs (THC:CBD oromucosal spray and matching placebo) that are identical in packaging, labelling, schedule of administration and in appearance.

At the conclusion of the study, when the database has been locked, the assigned blinded treatment codes will be broken and made available for the final statistical analysis.

Individual patient unblinding during the course of the trial will only be allowed in the event of patient emergencies on request from the investigator.

Experimental procedure

Preliminary setting and clinical evaluation

After the selection process and informed consent signature, all subjects will undergo a complete physical and neurological examination. The range of motion and MAS of the following segments will be assessed on both sides: elbow flexors, forearm pronators, wrist flexors, finger flexors, leg extensors, foot plantar flexor. The subjective amount of pain and muscle rigidity, quality of sleep and bladder dysfunction will be assessed using a 0–10 NRS, as well as the number of daily spasms. The amount of disability related to hygiene, dressing, limb position and pain will be also assessed by mean of the Disability Assessment Scale.35

Blood pressure and heart rate will also be evaluated during each scheduled visit and the patient's diary will be checked. The participants will be instructed about the medication dose uptitration process, patients’ diary fulfilment and next visit date. All patients will be given a portable blood pressure device and instructed to record daily blood pressure values at home.

Possible adverse events will be monitored during the entire duration of the study. The detailed schedule of assessments and procedures is reported in table 1.

Table 1.

Schedule of assessments and procedures

| Study Period | Screening and randomization | Period I | Wash-out | Period II |

| Visit | 1 (T0) | 2 (T1) | 3 | 4 (T2) |

| Informed consent | X | |||

| Demography | X | |||

| Medical and treatment history | X | |||

| Physical and neurological examination | X | X | X | X |

| Full cardio evaluation | X | |||

| Cardio consultation ‘as needed’ | X | X | X | |

| Vital signs | X | X | X | X |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | X | |||

| Modified Ashworth scale | X | X | X | |

| Spasticity NRS | X | X | X | |

| Stretch reflex evaluation | X | X | X | |

| Check patients diary | X | X | ||

| Spasticity NRS, Pain NRS, Bladder dysfunction NRS | X | X | ||

| Spasms number | X | X | ||

| Sleep quality NRS | X | X | ||

| Blood pressure and heart rate | X | X | ||

| Dispense study drug | X | X | ||

| Check of returned study drug | X | X | ||

| Adverse events | X | X | X | |

| Concomitant medications | X | X | X | X |

NRS, numerical rating scale.

Stretch reflex technical setup

The Biopac MP150 data acquisition system connected to a TSD130B twin-axis electronic goniometer (Biopac Systems, Goleta, CA, USA) will be used for data acquisition. The goniometer will be placed across the joint in order to optimally record the angle during the displacements with a sampling rate of 2 KHz. Electromyographic (EMG) activity produced by the stretched muscle will be recorded by surface electrodes (TSD150B, Biopac Systems) placed over the muscle belly. Movement timing will be paced by a software emulated metronome.

The subjects will be evaluated in a quiet room with a temperature between 21°C and 23°C. A limb segment presenting with spasticity between 1 and 3 at the MAS will be selected among flexor muscles of the wrist, flexor muscles of the elbow, extensor muscles of the leg, foot plantar flexor. If spasticity is detectable in more segments, in order to cause less discomfort to patients and examiners and prefer the choice of joints with a higher range of motion (allowing more accurate passive movement timing), the segments will be selected in the following order: wrist flexors, elbow flexors, leg extensors, foot plantar flexors (defined ‘selected segment’ and undergoing the stretch reflex procedure). For example, if a patient is affected by spasticity on both wrist flexors (MAS=2) and leg extensors (MAS=3), the stretch reflex procedure will be performed on wrist flexors. The subject will be seated if the selected segment is flexor muscles of the wrist, flexor muscles of the elbow; otherwise, the subject will be lying on a comfortable examination table in a supine (extensor muscles of the leg) position with head and shoulders slightly elevated, or prone (foot plantar flexors) with the feet protruding from the examination table in order to allow a full ankle range of movement.

Stretch reflex procedure

The method was described in detail in the first validating work.36 The method consists in moving the selected segment throughout the full range of motion in the time corresponding to the interval between two consecutive metronome tones. The increase or decrease of tone frequency (beats per minute (BPM)) determines a parallel change in the time required to perform a complete passive flexion or extension movement, so that given a certain range of motion, the mean movement velocity will be similarly modulated. The choice of the BPM will be done taking into account that low values could not be able to elicit a stretch reflex (especially in subjects with a low degree of spasticity), while high values could produce discomfort to the subject and excessive fatigue in the examiner. Continuous flexion and extension movements in a ‘sinusoidal’ way may be unsuitable to elicit and measure spasticity because of the possibility to trigger postactivation depression37 or paratonia.38 However, the method allows performing discontinuous (or ‘linear’) movements as well, by interposing a few tones interval between movements.

The subjects will be instructed to remain relaxed and to avoid resisting or facilitating the movements performed by the examiner. The stretch reflexes will be measured during movements determining elongation of the spastic muscle. At least 15 discontinuous stretch reflexes will be acquired during each experimental session. The recordings will be performed at each time point (T0, T1, T2) using the same metronome BPM. In order to obtain a reproducible electrode positioning between sessions, a picture of the electrode and its relation with nearby anatomical landmarks will be taken in each subject at T0. In order to reduce variability, the examiner performing the passive movements will be the same in all time points for each patient.36

Data analysis

The main end points of the study will be to assess the effect of THC:CBD oromucosal spray on spasticity measured with the stretch reflex and NRS for spasticity. To analyse the stretch reflex, the electromyographical recordings will be filtered, rectified and the average amplitude of the bursts will be calculated (mean EMG) using the dedicated AcqKnowledge analysis software (Biopac Systems). A mixed-model analysis of variance with GROUP (THC:CBD oromucosal spray, placebo) as between-subjects factor and TIME (T0, T1, T2) as within-subjects factor will be used to compare mean EMG values.

All semiquantitative rating scales scores will be compared between THC:CBD oromucosal spray/placebo groups using the Mann-Whitney test at each evaluation (T0, T1, T2). A comparison between T0 and T1 as well as between T0 and T2 will also be performed in each group using Wilcoxon test.

Since this is a pilot study, no formal sample size calculation can be done. It must be noticed, however, that in our previous study on patients with multiple sclerosis, we detected a significant reduction of the stretch reflex analysing 36 subjects.34

Ethics and dissemination

The study was registered on the EU Clinical Trials Register (EudraCT) database with number 2016-001034-10 and named ‘SativexStroke’. We received the approval from the Italian Medicines Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco) on 23 September 2016, the approval from the local Ethics Committee ‘Comitato Etico Regionale della Liguria’ on 14 December 2016 (protocol V.4.2) and the authorisation from ‘Ospedale Policlinico San Martino’ hospital on 3 March 2017 (decree number 227).

We plan to start patient recruitment in October 2017, after the drug has been produced and labelling completed. All study-related information will be stored securely at the study site and all participant information will be stored in locked file cabinets in areas with limited access. Electromyographical recordings and all the study-related files will be stored on a password-protected personal computer.

During the study, only the principal investigator will have access to the full data set. The final trial dataset will be blinded of any identifying participant information and uploaded to an open access data repository. The analysis will be probably completed by the end of 2019, after the 2-year study period. The data will be disseminated by presentation at national and international conferences and by publication in journals of clinical neuroscience and neurology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Paolo Ferri (Almirall Italia Spa) for his valuable support during protocol development and Dr Carlos Vila (Almirall SA, Barcelona, Spain) for his valuable contribution to protocol and manuscript revision.

Footnotes

Contributors: LM: principal investigator, study conception, manuscript drafting. MB, CS, CG: patients recruitment, evaluation of the cerebral vascular risk profile, manuscript review. LM, LP: co-investigators, technical setup, data acquisition. GR: cardiological evaluations and cardiovascular risk assessment. LG: study monitoring, adverse events tracking, administrative support. ACà, FF, GA, CT: clinical consultant and manuscript review.

Funding: This work will be partly supported by Almirall Italia. The study drugs (Sativex and Sativex placebo) will be provided by GW Pharmaceuticals without cost for the patient and for the Italian public health system.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: None.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committee “Comitato Etico Regionale della Liguria”.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Wissel J, Manack A, Brainin M. Toward an epidemiology of poststroke spasticity. Neurology 2013;80:S13–S19. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182762448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Collin C, Davies P, Mutiboko IK, et al. . Randomized controlled trial of cannabis-based medicine in spasticity caused by multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2007;14:290–6. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01639.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Collin C, Ehler E, Waberzinek G, et al. . A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of Sativex, in subjects with symptoms of spasticity due to multiple sclerosis. Neurol Res 2010;32:451–9. 10.1179/016164109X12590518685660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Novotna A, Mares J, Ratcliffe S, et al. . A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, enriched-design study of nabiximols* (Sativex),as add-on therapy, in subjects with refractory spasticity caused by multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2011;18:1122–31. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03328.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Etges T, Karolia K, Grint T, et al. . An observational postmarketing safety registry of patients in the UK, Germany, and Switzerland who have been prescribed Sativex (THC:CBD, nabiximols) oromucosal spray. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2016;12:1667–75. 10.2147/TCRM.S115014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Watson SJ, Benson JA, Joy JE. Marijuana and medicine: assessing the science base: a summary of the 1999 Institute of Medicine report. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:547–52. 10.1001/archpsyc.57.6.547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zachariah SB. Stroke after heavy marijuana smoking. Stroke 1991;22:406–9. 10.1161/01.STR.22.3.406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barnes D, Palace J, O'Brien MD. Stroke following marijuana smoking. Stroke 1992;23:1381. 10.1161/01.STR.23.9.1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mesec A, Rot U, Grad A. Cerebrovascular disease associated with marijuana abuse: a case report. Cerebrovasc Dis 2001;11:284–5. 10.1159/000047653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Geller T, Loftis L, Brink DS. Cerebellar infarction in adolescent males associated with acute marijuana use. Pediatrics 2004;113:e365–e370. 10.1542/peds.113.4.e365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mateo I, et al. . Recurrent stroke associated with cannabis use. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 2005;76:435–7. 10.1136/jnnp.2004.042382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Singh NN, Pan Y, Muengtaweeponsa S, et al. . Cannabis-related stroke: case series and review of literature. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2012;21:555–60. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oyinloye O, Nzeh D, Yusuf A, et al. . Ischemic stroke following abuse of Marijuana in a Nigerian adult male. J Neurosci Rural Pract 2014;5:417–9. 10.4103/0976-3147.140008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Inal T, et al. . Acute temporal lobe infarction in a young patient associated with marijuana abuse: An unusual cause of stroke. World J Emerg Med 2014;5:72–4. 10.5847/wjem.j.issn.1920-8642.2014.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Santos AF, Rodrigues M, Maré R, et al. . Recurrent stroke in a young cannabis user. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2014;26:E41–E42. 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.13020037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baharnoori M, Kassardjian CD, Saposnik G. Cannabis use associated with capsular warning syndrome and ischemic stroke. Can J Neurol Sci 2014;41:272–3. 10.1017/S0317167100016711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Urbano Seguí J, Falcón Espínola L, Expósito Rodríguez M, et al. . Cerebellar stroke by cannabis consumption. Med Clin (Barc) 2015;144:479–80. 10.1016/j.medcle.2015.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Freeman MJ, Rose DZ, Myers MA, et al. . Ischemic stroke after use of the synthetic marijuana “spice”. Neurology 2013;81:2090–3. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000437297.05570.a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bernson-Leung ME, Leung LY, Kumar S. Synthetic cannabis and acute ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2014;23:1239–41. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Takematsu M, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS, et al. . A case of acute cerebral ischemia following inhalation of a synthetic cannabinoid. Clin Toxicol 2014;52:973–5. 10.3109/15563650.2014.958614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jouanjus E, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Micallef J, et al. . Cannabis use: signal of increasing risk of serious cardiovascular disorders. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e000638. 10.1161/JAHA.113.000638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Endocannabinoids SR. blood pressure and the human heart. J Neuroendocrinol 2008;20:58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wolff V, Lauer V, Rouyer O, et al. . Cannabis use, ischemic stroke, and multifocal intracranial vasoconstriction: a prospective study in 48 consecutive young patients. Stroke 2011;42:1778–80. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.610915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thanvi BR, Treadwell SD. Cannabis and stroke: is there a link? Postgrad Med J 2009;85:80–3. 10.1136/pgmj.2008.070425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Capettini LSA, Savergnini SQ, da Silva RF, et al. . Update on the role of cannabinoid receptors after ischemic stroke. Mediators Inflamm 2012;2012:1–8. 10.1155/2012/824093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Choi I-Y, Ju C, Anthony Jalin AMA, et al. . Activation of cannabinoid CB2 receptor-mediated AMPK/CREB pathway reduces cerebral ischemic injury. Am J Pathol 2013;182:928–39. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Steffens S, Pacher P. Targeting cannabinoid receptor CB2 in cardiovascular disorders: promises and controversies. Br J Pharmacol 2012;167:313–23. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02042.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stanley CP, Hind WH, O'Sullivan SE. Is the cardiovascular system a therapeutic target for cannabidiol? Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013;75:313–22. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04351.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Malinowska B, Baranowska-Kuczko M, Schlicker E. Triphasic blood pressure responses to cannabinoids: do we understand the mechanism? Br J Pharmacol 2012;165:2073–88. 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01747.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lance JW. Symposium synopsis In: Feldman RG, Young RR, Koella WP, Spasticity: Disordered Motor Control, 1980:485–94. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bohannon RW, Smith MB. Interrater reliability of a modified Ashworth scale of muscle spasticity. Phys Ther 1987;67:206–7. 10.1093/ptj/67.2.206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Farrar JT, Troxel AB, Stott C, et al. . Validity, reliability, and clinical importance of change in a 0—10 numeric rating scale measure of spasticity: a post hoc analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Ther 2008;30:974–85. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Anwar K, Barnes MP. A pilot study of a comparison between a patient scored numeric rating scale and clinician scored measures of spasticity in multiple sclerosis. NeuroRehabilitation 2009;24:333–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Marinelli L, Mori L, Canneva S, et al. . The effect of cannabinoids on the stretch reflex in multiple sclerosis spasticity. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2016;31:232–9. 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brashear A, Zafonte R, Corcoran M, et al. . Inter- and intrarater reliability of the Ashworth Scale and the Disability Assessment Scale in patients with upper-limb poststroke spasticity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002;83:1349–54. 10.1053/apmr.2002.35474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marinelli L, Trompetto C, Mori L, et al. . Manual linear movements to assess spasticity in a clinical setting. PloS One 2013;8:e53627 10.1371/journal.pone.0053627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Trompetto C, Marinelli L, Mori L, et al. . The effect of age on post-activation depression of the upper limb H-reflex. European journal of applied physiology 2014;114:359–64. 10.1007/s00421-013-2778-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Marinelli L, Mori L, Pardini M, et al. . Electromyographic assessment of paratonia. Exp Brain Res 2017;235:949–56. 10.1007/s00221-016-4854-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.