Abstract

Translating neuroprotective treatments from discovery in cell and animal models to the clinic has proven challenging. To reduce the gap between basic studies of neurotoxicity and neuroprotection and clinically relevant therapies, we developed a human cortical neuron culture system from human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or inducible pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that generated both excitatory and inhibitory neuronal networks resembling the composition of the human cortex. This methodology used timed administration of retinoic acid (RA) to FOXG1 neural precursor cells leading to differentiation of neuronal populations representative of the six cortical layers with both excitatory and inhibitory neuronal networks that were functional and homeostatically stable. In human cortical neuron cultures, excitotoxicity or ischemia due to oxygen and glucose deprivation led to cell death that was dependent on N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, nitric oxide (NO), and the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP)-dependent cell death, a cell death pathway designated parthanatos to separate it from apoptosis, necroptosis and other forms of cell death. Neuronal cell death was attenuated by PARP inhibitors that are currently in clinical trials for cancer treatment. This culture system provides a new platform for the study of human cortical neurotoxicity and suggests that PARP inhibitors may be useful for ameliorating excitotoxic and ischemic cell death in human neurons.

INTRODUCTION

The human cerebral cortex is a complex structure with tightly interconnected excitatory and inhibitory neuronal networks that are organized in six layers (1, 2). The dynamic interplay between excitatory pyramidal cells and GABAergic interneurons begins at the early stages of neurogenesis (3). Considerable advances in methods that model human cortical development in human embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or inducible pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have allowed the generation of relatively pure populations of excitatory cortical projection neurons (4–6), forebrain inhibitory progenitors (7–11) and inhibitory neurons (12–14) or poorly characterized mixtures of excitatory and inhibitory neurons (15–17). Since no existing protocol produces a balanced network of excitatory and inhibitory neurons observed in the human cerebral cortex (see Fig S1) (4, 16–24), we sought to develop a suitable protocol that would yield appropriately balanced neuronal networks in vitro that closely resemble neuronal networks in vivo. This is particularly important when modeling glutamate excitotoxicity, because neuronal nitric oxide (NO) synthase (nNOS) expressing interneurons play a major role in the death of neurons in response to glutamate or ischemia (25–28).

The cerebral cortex is derived from forebrain FOXG1 expressing primordium (29). Here, we describe the production of a highly enriched population of forebrain region-specific FOXG1 neural precursor cells by the isolation of rosette neural aggregates (RONA, neural aggregates derived from rosette type of neural stem cells) from ESCs or iPSCs. Spontaneous fate determination of dorsal and ventral telencephalic progenitors, coupled with timed retinoic acid administration leads to differentiation of neurons into all classes of excitatory and inhibitory neurons in a balanced manner reflecting the mature human cerebral cortex. These cultures are sensitive to excitotoxic injury and cell death following oxygen-glucose deprivation that is mediated by the activation of NMDA receptors, nNOS and PARP. Clinically available PARP inhibitors are effective in blocking human cortical neuronal death. Thus, this method enables the study of excitatory and inhibitory functional networks and processes that are thought to play important roles in synaptic physiology and pathophysiology.

RESULTS

Isolation of FOXG1-positive forebrain progenitors

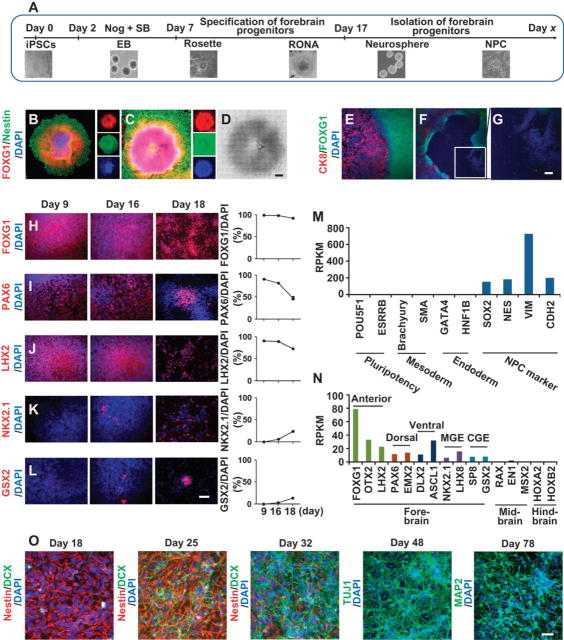

Human ESCs or iPSCs have intrinsic mechanisms enabling differentiation into different subtypes of neurons in the setting of appropriate cues (5, 30–32). We sought to develop a method to induce differentiation of human ESCs or iPSCs into FOXG1 forebrain progenitors to mimic the patterning and neurogenesis necessary to generate excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the same culture (Fig. 1A). First, human ESCs or iPSCs were detached and grown as embyroid body (EB) suspensions (18) (Fig. 1A). On day two, dual SMAD inhibition (31) with noggin and SB431542 was initiated for 4 days until day 7 to allow the robust induction of rosette formation (Fig. S2A–S2D). On day 7, the EBs were plated on matrigel or laminin precoated plates. At day 9 rosettes began to form that were FOXG1 and Nestin positive (Fig. 1B). Rosettes showed profound cellular expansion in a defined central area of each colony where they formed a RONA (Fig. 1C, D). The centers of these RONAs were FOXG1 positive and were surrounded by CK8 positive epithelial-like cells. This demarcation was easily identified under phase contrast microscopy without immunostaining, which allowed the manual isolation of the FOXG1 precursor cells, minimizing contamination of the non-neural precursors without the need for cell sorting (Fig. 1E–G). On day 17, RONAs were manually isolated and grown as neurospheres in suspension for one day. On day 18, the neurospheres were disassociated into single cells and plated on laminin/poly-D-lysine coated plates or coverslips where they formed neural precursor cell (NPC) clusters (Fig. 1A). To determine whether this isolation protocol resulted in the full complement of neural precursor subtypes (FOXG1, LHX2, PAX6, GSX2 and NKX2.1), which pattern the human cortical subdivision and specify cortical excitatory and inhibitory neurons (Fig. S2E), immunostaining for these markers was performed at day 9 (rosettes), day 16 (RONA) and day 18 (NPC) (Fig. 1H–L). The rosettes on day 9 were positive for the forebrain and dorsal markers FOXG1, PAX6 and LHX2 but not ventral telencephalic markers NKX2.1 or GSX2. On day 16, RONAs expressed all five cortical patterning related transcription factors, with FOXG1, PAX6 and LHX2 predominating and NKX2.1 and GSX2 expressed in patches at the periphery of RONAs (Fig. S2F–S2I). A comparable pattern was observed in human ESC (H1) and iPSC lines (SC1014, SC2131), with no significant differences observed among the different lines (Fig. 1H–1L and Fig. S2J). RNA sequencing was performed to gain a comprehensive and quantitative view of the transcriptome of isolated FOXG1 RONAs. Markers of pluripotency, mesoderm and endoderm were not detected. Pan-NPC markers (SOX2, NES, VIM, and CDH2) were highly expressed in isolated RONAs (Fig. 1M). Anterior forebrain markers FOXG1, LHX2 and OTX2 were highly expressed (Fig. 1N). Dorsal excitatory neuronal lineage markers (PAX6, EMX1 and EMX2) and ventral forebrain GABAergic neuronal markers (ASCL1 and DLX2) along with medial ganglionic eminence (MGE) markers (NKX2.1 and LHX8) and caudal ganglionic eminence (CGE) markers (GSX2 and SP8) were all expressed in isolated RONAs (Fig. 1N). Diencephalic (RAX), midbrain (EN1, MSX2), hindbrain (HOXA2, HOXB2) and more posterior markers (HOXA1, HOXB1, HOXC5, HOXB6 and HB9) were expressed at barely detectable levels (Fig. 1N). Complete ontology and enrichment analysis for all genes expressed in FOXG1 progenitors are shown in Data file S1. These results taken together indicate that the isolation of the FOXG1 RONAs provided a robust method for recapitulating the early induction of the human telencephalon (FOXG1) and its subsequent subdivision into dorsal (PAX6, LHX2) and ventral (NKX2.1) territories. These NPCs spontaneously differentiated into neurons after isolation from the RONAs and plating (Fig. 1O). These data suggested that the FOXG1 positive cells were being maintained in a precursor state prior to their isolation, and that they were capable of spontaneous differentiation into neurons when removed from the RONA niche.

Fig. 1. Generation of forebrain progenitor cells with regional identity from human iPSCs.

(A) Scheme of the rosette neural aggregates (RONA) differentiation protocol showing generation of forebrain progenitors from human ESCs and iPSCs. (B) Rosettes were immuno-positive for FOXG1 and Nestin at day 9 after initiation of neural differentiation. (C-D) With the prolongation of neural differentiation, highly proliferative rosettes started to pile up, resulting in 3-dimensional columnar cellular aggregates, which were positive for FOXG1 and Nestin. (D) Phase contrast image of RONA. B-D, scale bar, 50 µm. (E-G) FOXG1 immunoreactive RONAs were located in the center (E) and demarcated clearly with surrounding CK8-positive cells. (F) Cells underneath the RONAs were FOXG1−/CK8−. (G) The white inset box in (F) is magnified (2.5X). (H-L) Expression and quantification of the early forebrain regionalization markers FOXG1 (H), PAX6 (I), LHX2 (J), NKX2.1 (K) and GSX2 (L), after 9, 16, and 18 days of differentiation. Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m., n = 3. Scale bar, 20 µm. (M-N) RNASeq gene expression profiling of RONAs derived from H1 human ESC showing the enrichment of forebrain progenitors with regional identity. Data show the average RPKM (Reads Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads) value of two biological replicates of H1 human ESC RNAseq experiments. (O) Spontaneous neuronal differentiation after isolation of RONA neural progenitors without the application of exogenous mitogens. Nuclei were counterstained with 4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue). Colors are indicated in the images. Scale bar, 20 µm. Data are from human ESC H1 cell line in (B-O).

Induction of forebrain precursors with regional identity and differentiation of inhibitory neurons

In the absence of exogenous factors, the neural precursors expressed a complex combination of brain regional markers including FOXG1, PAX6, LHX2, NKX2.1, and GSX2 directly after isolation of RONAs (Fig. 1) indicating that these neuronal precursors had the potential capability of differentiating into both excitatory and inhibitory neurons. After isolation from RONAs, neural precursors spontaneously showed dynamic changes in cell identity. At day 19 close to 100% of the cells were FOXG1 positive and 50% were PAX6 positive and less than 5% were NXK2.1 positive (Fig. S3A–S3D). At day 24, 80% of the cells were PAX6 positive and 20% were NKX2.1 positive (Fig. S3A–S3D). After prolonged culture over 90% of these cells spontaneously differentiated into excitatory neurons, while less than 5–7% showed a mature inhibitory neuronal phenotype.

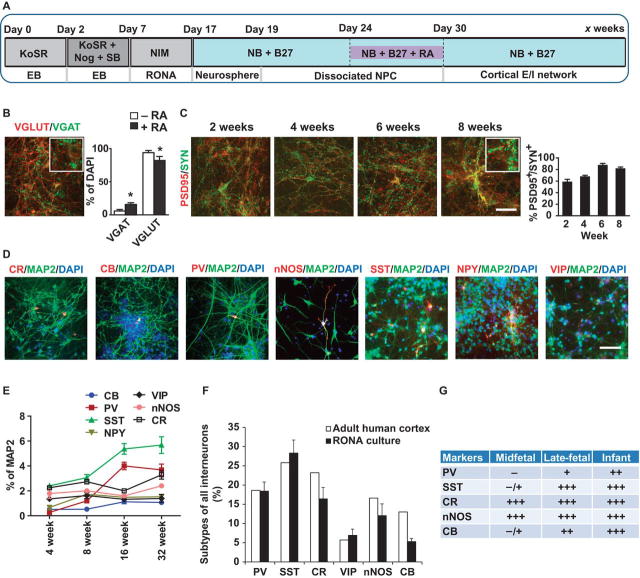

Since the composition of neurons in the human cerebral cortex is approximately 80% excitatory glutamatergic neurons and 20% GABAergic interneurons (1, 2) a better representative balance of excitatory and inhibitory neurons was needed. Accordingly, we explored whether retinoic acid or sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling could facilitate the optimal production of excitatory and inhibitory neurons (Fig. S3A–S3D). Retinoic acid (RA) and either sonic hedgehog (SHH) or the SHH pathway agonist Purmorphamine in various combinations were applied at day 19 and maintained for 6 days or were applied at day 24 and maintained for 6 days (Fig. S3A). Extensive optimization revealed that administration of RA at day 24 through 30 was required for maintaining the identity of both PAX6/FOXG1 and NKX2.1/FOXG1 progenitors and provided an appropriate percentage of excitatory and inhibitory neurons representative of the human cerebral cortex (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. Timing of retinoic acid/SHH exposure determines differentiation of excitatory and inhibitory neurons.

(A) Schematic summary of conditions for differentiation of appropriate balanced excitatory and inhibitory neurons. (B) Immunocytochemical analysis of excitatory marker VGLUT and inhibitory marker VGAT of cultured neurons. Quantification of the percentage of VGLUT-positive and VGAT-positive cells with or without retinoic acid (RA) exposure. Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m., n = 3. Significance was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey-Kramer’s post hoc test., * P < 0.05. (C) Immunocytochemical analysis of PSD95 (red) and Synapsin (green) following RA exposure from day 24 through day 30 after the initiation of neural differentiation. Quantification of the proportion of PSD95 puncta that were found associated with synapsin puncta. Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m., n = 3. (D) Differentiation of inhibitory neurons expressing subtype markers. Colors are indicated in the images. Scale bars, 20 µm. (E) Quantification of inhibitory neuron with immunostaining analyses over 32 weeks post differentiation. Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m., n = 3. (F) Composition of interneuron subtypes in adult human cortex (41) and the neuron culture derived from RONAs treated with RA. Data of cortical cultures derived from H1 human ESCs are represented as mean ± s.e.m. (G) Development pattern of parvalbumin (PV), somatostatin (SST), calretinin (CR), neuronal Nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), calbindin (CB) interneurons in human cortex from mid-fetal stage, late-fetal stage to infant (60). Data of human cortical cultures are from human ESC H1 cell line in (B-F).

Next the neural precursors were allowed to develop and differentiate after withdrawal of RA at day 30 while being maintained in neuronal differentiation media. Cultures were assessed at different time points for markers of excitatory and inhibitory neurons, as well as synaptogenesis. Two weeks after withdrawal of RA the cultures were composed primarily of TUJ1 positive neuronal cells (>90%) with about 5∼10% GFAP-positive astrocytes (Fig. 1O, Fig. S3E). Four weeks after the withdrawal of RA the neurons were comprised of approximately 15–20% inhibitory neurons as assessed by VGAT/GAD67 immunostaining and 80–85% excitatory neurons as assessed by VGLUT/CAMKII immunostaining (Fig. 2B and Fig. S3F). Two weeks after RA withdrawal, these neurons started to express the presynaptic marker synapsin and the postsynaptic marker PSD95 (Fig. 2C). These cultures expressed a variety of inhibitory neuronal markers that included calretinin (CR), calbindin (CB), parvalbumin (PV), neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), somatostatin (SST), neuropeptide Y (NPY), and vasointestinal polypeptide (VIP). Thirty-two weeks post-differentiation, the MAP2 positive neurons comprised approximately 3.2% CR, 1% CB, 3.68% PV, 2.5% nNOS, 5.67% SST, 1.53% NPY, 1.39% VIP positive neurons (Fig. 2D, E). A comparable composition was observed in cultures of the human iPSC SC1014 cell line (Fig. S3G). The composition of interneuron subtypes in adult human cortex and neuronal cells derived from RONA were compared. The RONA culture showed comparable composition of PV, SST, CR, VIP and nNOS interneurons to human adult cortex (Fig. 2F), and similar developmental patterns for PV, SST, CR, nNOS and CB interneurons when compared to human brain tissues (Fig. 2E, 2G). Furthermore, these cultures also expressed the NMDA receptor subunit NR1, the AMPA receptor subunit GluA1 and nNOS in a mature punctate pattern (Fig. S3H–3J). These data demonstrated that timed exposure to retinoic acid signaling directed differentiation of FOXG1 forebrain progenitor cells derived from human ESCs or iPSCs into excitatory neurons and a diverse repertoire of inhibitory neuronal subtypes with high efficiency.

Differentiation of layer specific cortical excitatory neurons from FOXG1+ forebrain progenitors

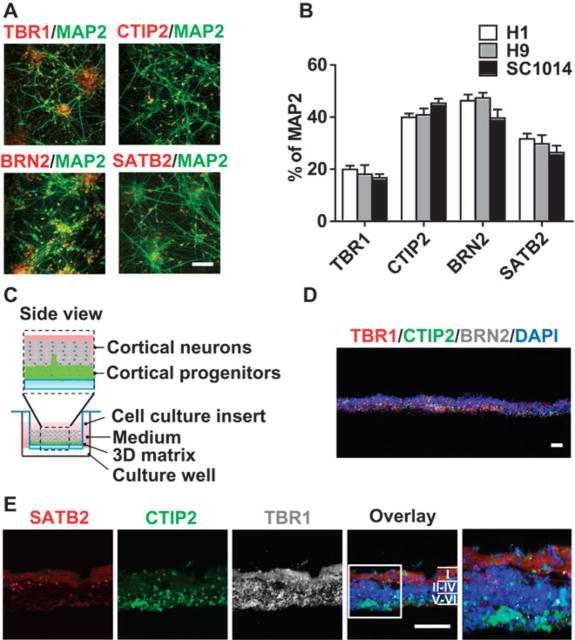

To determine whether the neurons expressed cortical layer specific markers 90 days after differentiation, immunostaining was performed for a set of neuronal specific transcription factors (Fig. 3A). The neuronal cultures expressed the cortical layer I, V, VI marker, TBR1; layer II-IV markers, BRN2 and SATB2; and layer V, VI marker CTIP2 (Fig. 3A). The proportion of upper superficial and deep layer cortical projection neurons was roughly the same in the differentiated cortical system across human ESC H1, H9 and human iPSC SC1014 cell lines (Fig. 3B). The human cerebral cortex is characterized by an organized six layered complex structure. In a modified three-dimensional basement membrane culture method (33–35) (Fig. 3C), immunostaining of cross-sections indicated that these neuronal cultures attempted to assemble into cortical layers with the deep layer cortical marker CTIP2 and the superficial cortical layer marker SATB2 tending to segregate into different orientations (Fig. 3D,3E).

Fig. 3. Generation of layer-specific human cortical neurons from FOXG1+ forebrain progenitor cells.

(A) Immunocytochemical analysis of cortical layer specific markers TBR1, CTIP2, BRN2, and SATB2 in human neuronal culture differentiated from FOXG1 neural progenitors derived from the H1 human ESC cell line. (B) Quantification of the percentage of TBR1, CTIP2, BRN2, and SATB2 in neuronal culture. Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m., n = 3. Data are from human ESC cell lines H1, H9 and human iPSC cell line SC1014. (C) Diagram for 3D human cortical assemblies assay. (D-E) Cross-sections from 3D human cortical assemblies were immune-stained with the cortical neuron layer markers TBR1, CTIP2, BRN2, and SATB2. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). The boxed area is magnified (2.5X) in the fifth column of (E). Colors are indicated in the images. Scale bar, 50 µm. Data in C-E are from the H1 human ESC cell line.

Functional human cortical excitatory and inhibitory networks show homeostasis

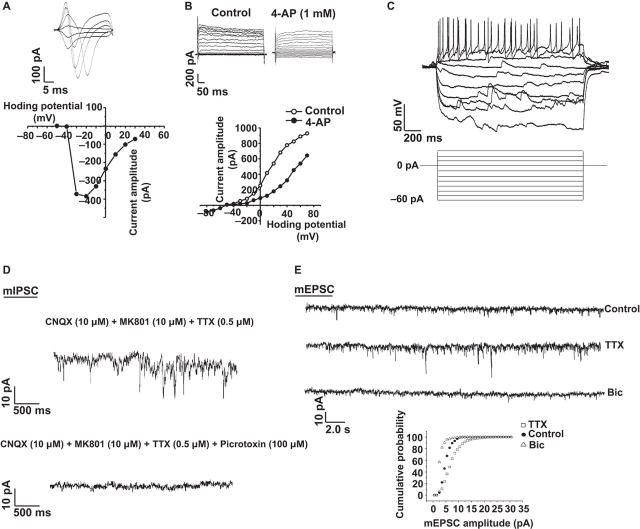

Eight weeks post-differentiation, electrical properties of human ESC derived cortical neurons were measured. Whole cell patch clamp recording of the neurons revealed the presence of voltage-gated sodium currents that were blocked by tetrodotoxin (Fig. 4A and Fig. S4A). In addition, there were voltage-gated potassium currents that were sensitive to potassium channel blocker 4-aminopyridine (Fig. 4B). Human ESC derived cortical neurons fired action potentials when they were depolarized, but not when they were held at low membrane potential (Fig. 4C). To test whether the excitatory and inhibitory synapses (see Fig. 2B, C) were functional under physiological conditions, miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) and miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) were detected by whole cell patch clamp recording. To probe the dynamics of mIPSCs during the development of the neuronal network, the properties of mIPSCs in amplitudes and frequencies were recorded and analyzed over time, revealing a kinetic change over the time measured (Fig. S4B). At 8 weeks after induction of neuronal differentiation, consistent with the presence of GABAergic synaptic inputs, whole-cell patch-clamp analysis demonstrated that cells readily received inhibitory postsynaptic currents that could be reversibly blocked by a GABAA receptor inhibitor picrotoxin in the presence of the NMDA receptor antagonist MK801 or the AMPA receptor antagonist 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2, 3-dione (CNQX) (Fig. 4D). The mEPSCs were frequently detected in the presence of picrotoxin with 5–15 pA amplitude. The amplitude and frequency of mEPSCs of these cortical neurons increased over time (Fig. S4C).

Fig. 4. Development of a functional human cortical excitatory and inhibitory neuronal network.

(A-B) Voltage-gated sodium (A) and potassium channels (B) present in human ESC-derived cortical neurons. n = 10 for sodium current, n = 12 for potassium current. (C) Evoked action potentials (whole-cell recording, current clamping) generated by H1 human ESC-derived cortical neurons after 8 weeks of differentiation; n = 9. (D) Measurement of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) indicated the formation of a functional inhibitory network in human cortical neuronal culture. 40 mM chloride ion in pipette solution, the mIPSCs current is inward; n = 11 for each group. (E) Homeostatic scaling of H1 human ESC-derived cortical neurons. Measurement of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) from cultured human cortical neurons under control conditions (control), conditions of activity blockade (tetrodotoxin, TTX), or conditions of activity enhancement with bicuculline (Bic). 48 hours of activity blockade increased the amplitude of mEPSCs, whereas 48 hours of enhanced activity decreased the mEPSC amplitude. Mann-Whitney test, * P < 0.05. Control, n = 17; TTX, n = 21; Bic, n = 18. Data shown are from the human ESC cell line H1 in (A-E).

Synaptic scaling homeostatically regulates the stability of network activity by balancing excitation and inhibition (36). To examine whether the existing functional network could undergo synaptic scaling, homeostatic scaling was assessed in human ESC derived cortical neurons treated for 36 to 48 hr with tetrodotoxin (1 µM), which blocked all evoked neuronal activity, or bicuculline (20 µM), which blocked inhibitory neurotransmission mediated by GABAA receptors and increased neuronal firing (37). There was a robust increase in the amplitude of mEPSCs following tetrodotoxin treatment (Fig. 4E), which was present four weeks post-differentiation and further increased after eight weeks (Fig. 4E, Fig. S4D, 4E). A rightward shift of the cumulative probability distributions indicated that the increase in amplitude was distributed across the range of recorded events. In contrast to the increase in mEPSCs following tetrodotoxin treatment there was a robust decrease in the amplitude of mEPSCs following bicuculline treatment (Fig. 4E), which began at four weeks post-differentiation and was more robust after eight weeks (Fig. 4E, Fig. S4D, 4E). There was a leftward shift of the cumulative probability distributions, indicating that the decrease in amplitude was distributed across the range of recorded events (Fig. 4E). These results show that the differentiated neurons formed a functionally balanced excitatory and inhibitory network and neuronal activity could be homeostatically regulated to maintain network stability.

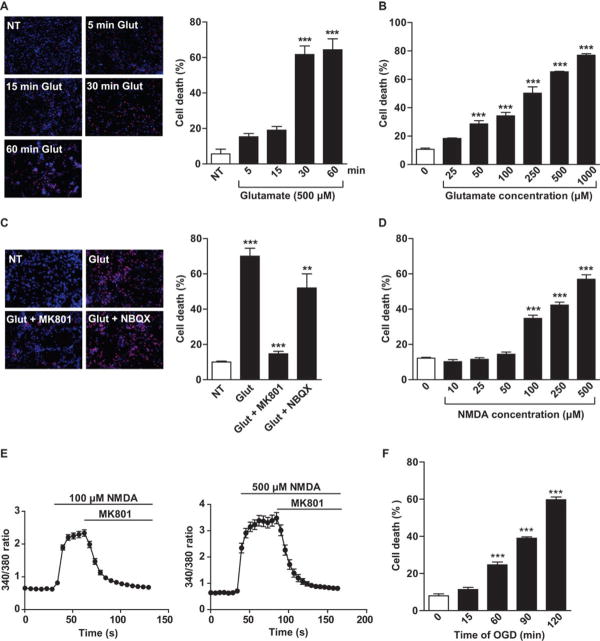

Human cortical neurons are sensitive to NMDA and oxygen-glucose deprivation neurotoxicity

To ascertain the susceptibility of human cortical neurons to excitotoxicity, human cortical neurons derived from H1 human ESCs were exposed to 500 µM glutamate for 5 min, 15 min, 30 min or 60 min. Greater than 60% of neurons died after a 30 min exposure to 500 µM glutamate as assessed 24 hours later. Exposure to 500 µM glutamate for 5 min or 15 min resulted in lower neurotoxicity (Fig. 5A). A dose response to increasing concentrations of glutamate indicated that human cortical neurons were sensitive to a graded concentration of glutamate with greater than 60% toxicity achieved with 500 µM glutamate for 30 min (Fig. 5B). Glutamate neurotoxicity was markedly attenuated by the NMDA receptor antagonist MK801 but only a modest protection was observed with the AMPA receptor antagonist NBQX (Fig. 5C). Since glutamate neurotoxicity in human neurons occurred predominantly through NMDA receptors, subsequent studies were focused on NMDA receptor stimulation by using NMDA to activate the NMDA glutamate receptor subtype. A time course of 500 µM NMDA was performed and revealed a similar pattern of neurotoxicity with approximately 60% neuronal cell death after a 30 min exposure and no or modest toxicity following 5 min or 15 min exposure to 500 µM NMDA assessed 24 hours later (Fig. S5A). A dose response to increasing concentrations of NMDA indicated that human cortical neurons derived from H1 human ESCs were sensitive to a graded concentration of NMDA with greater than 60% toxicity achieved with 500 µM NMDA for 30 min (Fig. 5D). Calcium ion influx triggered by exposure to NMDA (100 µM or 500 µM) is almost fully abolished by the addition of MK-801 (Fig. 5E). Human cortical neurons were also sensitive to oxygen-glucose deprivation with cell death observed after 60 minutes of oxygen-glucose deprivation and with greater than 60% cell death observed with exposure to 120 minutes of oxygen-glucose deprivation assessed 24 hours later (Fig. 5F). Human cortical cultures derived by a similar protocol, but without retinoic acid treatment, were challenged with different doses and exposure times of glutamate or NMDA, or different exposure times of oxygen-glucose deprivation to compare their sensitivity to excitotoxicity in the presence or absence of retinoic acid treatment (Fig. S5B–S5F). The absence of retinoic acid treatment led to less sensitivity of human neuronal cultures to glutamate, NMDA and oxygen-glucose deprivation neurotoxicity (Fig. S5B–S5F).

Fig. 5. Characterizing human cortical neurons as a model for excitotoxicity.

(A) Percentages of neuron death were assessed by Propidium Iodide (PI)/Hoechst stain 24 hours after different exposure times to 500 µM glutamate, and were quantified and expressed as mean ± s.e.m, n = 3. (B) Percentages of neuron death were assessed by PI/Hoechst stain 24 hours after 30 minutes of glutamate exposure at different doses, and were quantified and expressed as mean ± s.e.m, n = 3. (C) MK801 (antagonist of NMDA receptors) but not NBQX (antagonist of AMPA receptors and kainate receptors) abolished 500 µM glutamate-induced human cortical neuron death. Percentages of neuron death were quantified and expressed as mean ± s.e.m, n = 3. Glutamate significantly kills neurons (*** P < 0.001) and MK801 significantly protects against glutamate excitotoxicity (*** P < 0.001), while NBQX has no significant effect on glutamate excitotoxicity. (D) 30 minutes of treatment with NMDA at different concentrations. Percentages of neuron death were assessed by PI/Hoechst stain, quantified and expressed as mean ± s.e.m, n = 9. (E) Calcium imaging with Fura-2 of human cortical neuron cultures stimulated with 100 or 500 µM NMDA and 10 µM glycine, followed by MK801. Plots show mean ± s.e.m. of 30–31 neurons. (F) Human H1 human ESC derived cortical neurons were subjected to different lengths of oxygen-glucose deprivation . Percentages of neuron death were assessed by PI/Hoechst stain, quantified and expressed as mean ± s.e.m, n = 9. (A-F) Significance was determined by analysis of ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-test, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

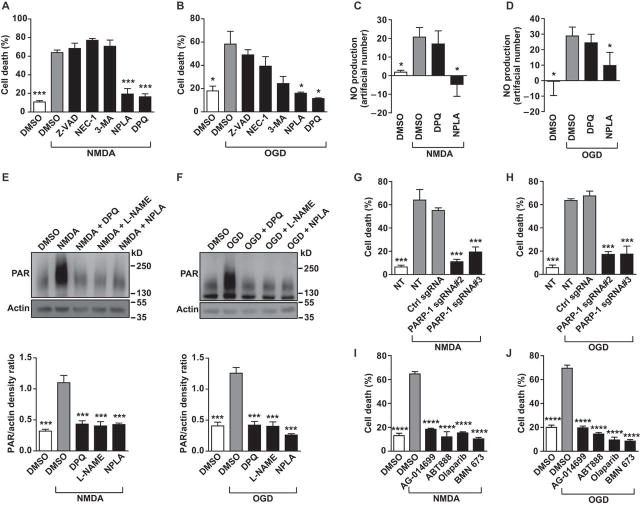

NMDA excitotoxicity and oxygen-glucose deprivation neurotoxicity are mediated by nitric oxide and parthanatos

To evaluate mechanisms involved in NMDA or oxygen-glucose deprivation neurotoxicity in human cortical neurons derived from H1 human ESCs, cell death was assessed following exposure to NMDA or oxygen-glucose deprivation in the presence of antagonists to known cell death signals. Only the selective nNOS inhibitor, NPLA, and the PARP inhibitor, DPQ, blocked NMDA or oxygen-glucose deprivation neurotoxicity (Fig. 6A, 6B). Since nNOS neurons play a critical role in excitotoxicity, we quantified and compared the percentage of nNOS neurons in retinoic acid and non- retinoic acid induced human neuronal cultures after two months of differentiation. We observed less nNOS positive neurons in non- retinoic acid treated cultures compared to retinoic acid -treated cultures, which may partly explain the reduced sensitivity to excitotoxicity in non- retinoic acid -treated cultures (Fig. S5G). The broad-spectrum caspase inhibitor Z-VAD, the necroptosis inhibitor necrostatin-1 (NEC-1), or the autophagy inhibitor 3-MA, were not effective in altering NMDA or oxygen-glucose deprivation neurotoxicity (Fig. 6A, 6B). NMDA-induced and oxygen-glucose deprivation -induced nitric oxide formation was measured by Measure-iT High-Sensitivity Nitrite Assay Kit (38). The selective nNOS inhibitor NPLA attenuated nitric oxide production consistent with its neuroprotection while the PARP inhibitor had no effect (Fig. 6C, 6D). NMDA-induced or oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced PARP activity was assessed by a PAR immunoblot assay. The PARP inhibitor DPQ and nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitors L-NAME or the selective nNOS inhibitor NPLA attenuated PAR formation (Fig. 6E, 6F). To confirm that activation of PARP was critical to NMDA or oxygen-glucose deprivation neurotoxicity, PARP-1 was knocked out by CRISPR/Cas9 using two different single guide RNAs (sgRNA) (Fig. S6A). Knockout of PARP-1 by either sgRNA substantially attenuated NMDA or oxygen-glucose deprivation neurotoxicity (Fig. 6G, 6H). Furthermore, four PARP inhibitors that are currently being evaluated in clinical trials for cancer were evaluated for neuroprotective actions against NMDA or oxygen-glucose deprivation neurotoxicity. AG-014699, ABT-888, olaparib and BMN-673 all markedly attenuated NMDA or oxygen-glucose deprivation neurotoxicity in human cortical neurons (Fig. 6I, 6J). In rodent models, questions have been raised regarding the role of PARP activation in male versus female mice (39). Thus, human cortical neurons were derived from the H9 human ESC cell line which is female for comparison to H1 male human ESC-derived cortical cultures. Under identical conditions, we observed that NMDA or oxygen-glucose deprivation elicited identical neurotoxicity in the H1 versus H9 derived cortical cultures that was attenuated by the PARP inhibitors equally in both cortical cultures (Fig. S6B–6G).

Fig. 6. Pathways involved in human cortical neuronal death induced by NMDA and oxygen-glucose deprivation.

(A, B) NPLA (selective nNOS inhibitor) and DPQ (PARP inhibitor), but not Z-VAD (caspase inhibitor), NEC-1 (necroptosis inhibitor) or 3-MA (autophagy inhibitor), protected human H1 human ESC derived cortical cultures from cell death due to (A) 30 min of 500 µM NMDA or (B) 2 hours of oxygen-glucose deprivation treatment. Quantitative data of PI/Hoechst positive cell number ratio is shown as mean ± s.e.m. In NMDA-treated neurons, n = 8 for DMSO control groups. In oxygen-glucose deprivation-treated neurons, n = 3 for DMSO control groups. In NMDA and oxygen-glucose deprivation treated neurons n = 3 for Z-VAD, NEC-1, 3-MA, NPLA and DPQ groups. (C-D) An nNOS inhibitor (NPLA) but not a PARP-1 inhibitor (DPQ), inhibited nitric oxide (NO) production in H1 cortical cultures after 30 minutes treatment with 500 µM NMDA or 2 hours of oxygen-glucose deprivation . Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m. of NO (nitric oxide) units (fluorescence measured at excitation/emission 365nm/450nM) normalized to medium-only wells, n = 4. (E-F) Representative blots showing that treatment with an nNOS inhibitor (NPLA or L-NAME) or DPQ blocked PAR polymer formation (the product generated by PARP) after 30 minutes treatment with 500 µM NMDA or 2 hours of oxygen-glucose deprivation treatment in H1 human ESC derived cortical cultures, mean ± s.e.m. of PAR polymer/actin band density ratio, n =3. (G-H) Lentiviral vector based PARP-1 CRISPR/Cas9 sgRNAs protect H1 human ESC derived cortical cultures from NMDA or oxygen-glucose deprivation -induced death. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m., n = 3. (I-J) PARP-1 inhibitors protect H1 cortical cultures from NMDA or oxygen-glucose deprivation -induced cell death. Data are shown as mean ± s.e.m., n = 4. (A-J) Significance was determined by analysis of ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post-test, * P <0.05, ** P <0.01, *** P <0.001, **** P <0.0001.

DISCUSSION

This study presents an efficient method for differentiation of human ES or iPS cells into excitatory and inhibitory neurons by isolation of highly enriched FOXG1 neural precursors from human ESC or iPSC RONAs. In particular, timed RA administration led to balanced excitatory and inhibitory neuronal networks that exhibited all six layers of cortical projection neurons and a rich diversity of GABAergic interneurons. This method enabled the formation of functional excitatory and inhibitory networks that exhibited homeostatic scaling and susceptibility to excitotoxicity and oxygen-glucose deprivation in a nitric oxide and PARP-dependent manner.

FOXG1 is one of the earliest expressed transcription factors that directs development of the telencephalon (29). In the mouse brain, FOXG1 is required for the development of both the ventral telencephalon and the anterior neocortex, thus providing a source of both excitatory and inhibitory neurons (29, 40). Following efficient neuroectoderm conversion of human ESCs or iPSCs expressing high levels of FOXG1, these FOXG1 precursors expressed markers of the dorsal forebrain (PAX6 and LHX2) and ventral forebrain (NKX2.1 and GSX2). The RONA culture method described here does not require cell sorting, is cost effective using minimal numbers of expensive growth factors, and should be a widely applicable method. It supports the formation of cortical dorsal and ventral subdivisions, reminiscent of forebrain patterning along the dorso-ventral axis. This method results in approximately 20% inhibitory neurons, which is reflective of the known abundance of inhibitory neurons in both mouse and human brain tissue (1, 2). The expression of nNOS neurons in human brain and RONA-derived neuron culture is equivalent to that observed in mouse and human brain (41, 42). The composition of PV, SST, CR, VIP and nNOS in interneuronal culture derived from RONAs is similar to those in human adult cortex (41), which indicates the percentage of these interneuronal populations is more reflective of human rather than mouse cortex. A review of other human cortical neuron differentiation and culture methods indicates that the method described here provides a more balanced representation of both excitatory and inhibitory neurons than previously reported methods (Fig. S1). There is a modest under representation of nNOS, CR and CB interneurons (Figure 2 and Fig S1) and future studies and optimization will be required to provide a more accurate representation of the interneuron composition of the human cortex. The composition of PV, SST and VIP interneurons shared by RONA-derived neurons and the human cortex differs from the mouse brain, thus RONA-derived human neurons may be more suitable for studying neurological diseases involving human excitatory and inhibitory neuronal networks. In addition to the highly enriched neuron culture 8 to 12 weeks post induction of neural differentiation, we observed that approximately 5 to 10% of the cells were GFAP positive astrocytes, which is consistent with the astrogenesis pattern shown in 3-D cultures of laminated cerebral cortex–like structures (43).

Proper brain function requires a balance of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission (36). In neurological and neuropsychiatric diseases such as autism, Alzheimer disease, and schizophrenia, there is evidence that the balance of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission is disturbed (44). There has been progress in establishing in vitro systems for studying human disease using populations of either mature cortical interneurons, excitatory pyramidal neurons or mixed neural cultures with limited characterization of the interplay between excitatory and inhibitory networks. The protocol described here provides a more accurate representation of the human cortex allowing the study of the interplay between excitatory and inhibitory networks in both normal and pathological conditions. This method generates functional neurons with relatively mature electrical properties including excitatory and inhibitory postsynaptic currents, mEPSCs and mIPSCs, which are indicative of the co-presence of excitatory and inhibitory networks. In response to neural activity, neuronal networks undergo compensatory synaptic scaling to maintain a proper balance of excitation and inhibition (45). Our cortical cultures exhibit homeostatic scaling as pharmacological perturbation by tetrodotoxin and bicuculline results in adaptive synaptic function. Homeostatic scaling has been widely studied in rodent models and our data indicate that homeostatic scaling can occur in human cortical neurons as well.

Although cultured human fetal cortical neurons are sensitive to glutamate neurotoxicity (46), the underlying mechanisms of glutamate excitotoxicity has not been explored in human neuronal cultures (47, 48). The dynamic interplay between inhibitory neurons and pyramidal excitatory neurons is particularly important in studying neurotoxicity or neuronal injury. In particular, modeling excitotoxicity in primary neuronal cultures from mice and rats requires the presence of nNOS inhibitory neurons (27, 28, 49, 50). A recent study of NMDA excitotoxicity in human embryonic-derived excitatory neurons required a 24 hour exposure to NMDA to elicit neurotoxicity (47). The requirement of prolonged exposure to NMDA to elicit excitotoxicity is dramatically different from the rapidly triggered delayed death that is characteristic of acute neuronal injury that occurs in stroke or trauma (51). On the other hand, the human neuronal culture method reported here exhibited rapidly triggered delayed death in response to glutamate and NMDA excitotoxicity and oxygen-glucose deprivation. The enhanced susceptibility is most likely due to an appropriate balance of excitatory and inhibitory neurons (52), including nNOS neurons. Our method revealed that human neurons are sensitive to nitric oxide and parthanatos, similar to rodent neuronal cultures, cortical brain slices and in vivo animal studies (26, 49, 53–58). Since neuronal cell death is dependent on the length and strength of the stimulus, it is possible that other cell death pathways may be recruited with longer exposure to excitotoxins or oxygen-glucose deprivation . However, in acute injury paradigms, nitric oxide and parthanatos predominate much in the same manner as has been reported in rodent model systems (26, 53, 57, 59). These results are consistent with the notion that interfering with parthanatos is a particularly attractive approach to treat acute neuronal injury in humans, particularly since there are clinically available PARP inhibitors (54).

In summary, we report a robust and easily reproducible system for generation of excitatory projection neurons and inhibitory interneurons. These human cortical neurons can be used to study mechanisms of excitotoxicity and screen for clinically relevant neuroprotective compounds. Furthermore, in future studies, this methodology can be used to generate cultures that will be useful in exploring the genetic basis of neuronal connectivity in neuropsychiatric diseases such as autism and schizophrenia, which are thought to involve imbalances in excitatory and inhibitory neural transmission. Moreover, these cultures may be useful in the study of neurodegenerative diseases relevant to the cortex including Alzheimer’s disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

To ensure adequate power to detect an effect size, the effect size was first calculated based on pilot experiments, and then used in power analysis by the software G*Power to determine sample size by given error probability (α = 0.05) and power (1-β > 0.95). All samples were included for data analysis. Imaging and cell count for neural differentiation and neurotoxicity were performed by either automated software or blinded observer. NIH registry human ES cell lines H1 and H9 (which are widely distributed and researched) and two characterized human iPS cell lines SC1014 and SC2131 (reprogrammed by non-integrating Sendai virus and lentivirus) were used for the neural differentiation and neurotoxicity assays. The human ESC/iPS cell lines used and quantified in all the experiments are described in individual figures and figure legends.

Human ESCs or iPSCs culture

human ESC lines H1, H9 (WiCell), and human iPSC lines SC1014, SC2131 (JHMI) were maintained on inactivated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) according standard protocol1. Briefly, human ESCs or iPSCs were maintained in human ES cell medium containing DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen), 20% knockout serum replacement (KSR, Invitrogen), 4 ng/ml FGF2 (PeproTech), 1 mM Glutamax (Invitrogen), 100 µm non-essential amino acids (Invitrogen), 100 µM 2-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen). Medium was changed daily. Cells were passaged using collagenase (1 mg/ml in DMEM/F12) at a ratio 1:6 to 1:12. All experiments using human ESCs/iPSCs cells are conducted in accordance with the policy of the JHU SOM that research involving human ESCs or iPSCs being conducted by JHU faculty, staff or students or involving the use of JHU facilities or resources shall be subject to oversight by the JHU Institutional Stem Cell Research Oversight (ISCRO) Committee.

Neural differentiation of human ESCs or iPSCs

To initiate differentiation, human ESCs or iPSCs colonies were allowed to incubate with Collagenase (1 mg/ml in DMEM/F12) in the incubator for about 5–10 min. The colony borders will begin to peel away from the plate. Gently wash the Collagenase off the plate with growth medium. While the colony center remains attached, the colonies were selectively detached with the MEFs undisturbed. Detached ESCs or iPSCs colonies were then growing as suspension in human ES cell medium without FGF2 for 2 days in low attachment 6-well plates (Corning). From day 2 to day 6, Noggin (50ng/ml, R&D system) or Dorsomorphin (1µm, Tocris) and SB431542 (10µm, Tocris) were supplied in human ES cell medium (without FGF2, defined as KoSR medium). On day 7, free-floating EB were transfer to Matrigel or Laminin precoated culture plates to allow the complete attachment of EB aggregates with the supplement of N2-induction medium (NIM) containing DMEM/F12 (Invitrogen), 1% N2 supplement (Invitrogen), 100 µm MEM non-essential amino acids solution (Invitrogen), 1 mM Glutamax (Invitrogen), Heparin (2 µg/ml, Sigma). Continue feeding with N2-medium every other day from day 7–12. From day 12, N2-induction medium were changed every day. Attached aggregates will breakdown to form a monolayer colony on day 8–9 with typical neural specific rosette formation. With the extension of neural induction, highly compact 3-dimentional column-like neural aggregates (termed rosette neural aggregates , RONA) formed in the center of attached colonies. RONAs were manually microisolated taking special care to minimize the contaminating peripheral monolayer of flat cells, and cells underneath RONAs. RONA clusters were collected and maintained as neurospheres in Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) containing B27 minus VitA (Invitrogen), 1 mM Glutamax (Invitrogen) for 1 day, the next day, neurospheres were dissociated into single cells and plated on Laminin/PDL coated plates for further experiments. For neuronal differentiation, either RA (2µM), SHH (50ng/ml), Purmorphamine (2µM), or the combination of RA, SHH, Purmorphamine were supplemented in neural differentiation medium containing Neurobasal/B27 (NB/B27; Invitrogen), BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor, 20ng/ml; PeproTech), GDNF (glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, 20 ng/ml; PeproTech), ascorbic acid (0.2 mM, Sigma), dibutyryl cAMP (0.5 mM; Sigma) at indicated time after neurospheres were dissociated into single cells. For long term neuronal culture, neural differentiation medium containing rat astrocyte-conditioned Neurobasal medium/B27, BDNF, GDNF, ascorbic acid, dibutyryl cAMP was used for maintenance.

RNA Seq

Two biological replicates of RONA colonies were dissected away from supporting cells, disassociated and plated. Twenty-four hours after plating, total RNA was harvested from culture using Trizol (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Ribosomal RNAs were subtracted from total RNA using RiboZero magnetic kit (Epicentre). Libraries from rRNA-subtracted RNA were generated using ScriptSeq 2 (Epicentre) and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500. Reads were mapped to the human genome (release 19) using TopHat2. Reads were annotated using a custom R script using the UCSC known Genes table as a reference. Gene ontology shows output from a enrichment analysis on DAVID (david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/), searching the following categories: GO Biological Process, GO Molecular Function, PANTHER Biological Process, PANTHER Molecular Function, KEGG and PANTHER pathway. Enrichment terms and associated genes and statistics are presenting with additional statistical analyses also provided. P-values presented in the text are corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini method (column L).

Immunocytochemistry, immunohistochemistry, imaging and quantification

Cultured cells were washed in PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. Attached RONAs and human cortical assemblies were sectioned (25 µm) by cryostat (CM3050; Leica, Nussloch, Germany) and collected on SuperFrost Plus glass slides (Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany). Cells and sections were blocked with blocking buffer containing 10% v/v donkey serum and 0.2% v/v Triton X-100 in PBS. Primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer were incubated overnight at 4°C, washing three times in blocking buffer, treatment with secondary antibody (Invitrogen) were applied for 1 hr and washing three times in blocking buffer. After staining, coverslips were mounted on glass slides and sections were coverslipped using prolong gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen). Primary antibodies are: Human specific Nestin (Millipore, MAB5326), Human specific Nestin (Millipore, MAB5922), PAX6 (COVANCE, PRB-278P), FOXG1 (Abcam, ab18259), CTIP2 (Abcam, ab18465), SATB2 (Abcam, ab51502), BRN2 (SantaCruz, sc-6029), TBR1 (Abcam, ab31940), DCX (SantaCruz, sc-8066), β-tubulin III (TUJ1, Millipore, AB1637), MAP2 (Sigma, M2320), MAP2 (Millipore, AB5622), nNOS (Sigma, N2880), VGLUT1 (SYSY, 135311), Synapsin I (Millipore, AB1543), PSD95 (Abcam, ab2723), VGAT (SYSY, 131003), Parvalbumin (Sigma, P3088), Calbindin (Sigma, C9848), Calretinin (BD, 610908), Somatostatin (Millipore, MAB354), GSX2 (Abcam, ab26255), NKX2.1 (TTF1, Epitomics, 2044–1), VIP (Sigma, V0390), NPY (Abcam, ab30914), PROX1 (Abcam, ab37128), CK8 (SantaCruz, sc-101459), LHX2 (Millipore, AB10557), GluN1 (SYSY, 114011) , GluA1 (Epitomics, 1308–1), CAMKII (Cell Signaling Technology, 3362S) and GAD67 (Millipore, MAB5406).The following cyanine 2 (Cy2)-, Cy3-, and Cy5-conjugated secondary antibodies were used to detect first antibodies: donkey antibody against mouse, donkey antibody against rat, donkey antibody against goat and donkey antibody against rabbit (Invitrogen).

3D human cortical assembly assay

The cell culture insert was initially coated with 2% Matrigel, forming a gelled bed of basement membrane. Isolated NPC were seeded onto this bed as a single-cell suspension at a high density of 0.75∼1×106/cm2 in a neural differentiation media containing Neurobasal/B27 (NB/B27; Invitrogen), 1% Matrigel, BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor, 20 ng/ml), GDNF (glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, 20 ng/ml), ascorbic acid (0.2 mM), and dibutyryl cAMP (0.5mM). The neural differentiation media is replaced every 3 days.

Oxygen-glucose deprivation

Dissolved O2 was first removed from glucose free media by bubbling with oxygen-glucose deprivation gas (5% CO2, 9.8% Hydrogen, and 85.2% N2, Airgas Ltd. USA) for 30 min2. Neurons were then washed with glucose free media. oxygen-glucose deprivation was started by addition of glucose free media pre-bubbled with oxygen-glucose deprivation gas following incubation in a hypoxia chamber attached with O2 sensor/monitor (Biospherix Ltd. USA) for indicated time. Neuron cultures were then re-fed with normal media and maintain in normal culture condition (5%CO2 and 20% O2 at 37°C).

Cell death assessment

Two to three month old human cortical neurons were treated with NMDA or oxygen-glucose deprivation at various indicated time duration and doses. Percent of cell death was determined by the staining with 5 µM Hoechst 33342 and 2 µM propidium iodide (PI) (Invitrogen, Carlsbas, CA). Images were taken and counted by Zeiss microscope equipped with automated computer assisted software (Axiovision 4.6, Zeiss). 20 µM Z-VAD (Sigma, V116), 20 µM NEC-1 (Sigma, N9037), 500 µM 3-MA (Calbiochem, 189490), 20 µM NPLA (Tocris, 1200), 30 µM DPQ (Enzo, ALX-270-21-M005), 500 nM AG-014699 (Selleckchem, S1098) 10 µM ABT888 (Active biochem, A-1003), 2 µM Olaparib (LC laboratories, O-9201) and 20 nM BMN673 (Selleckchem, S7048) were applied to evaluate the effect of different antagonists to known cell death signals.

Calcium imaging

Human cortical neurons were administrated with Fura 2 (Molecular Probes) for 30 min at room temperature. After washing, calcium imaging was conducted at 340 and 380 nm excitation in two month-old human cortical neuron cultures. Neurons were stimulated with 100 or 500 µM NMDA followed by MK801 to detect intracellular free calcium.

Measurement of NO production in culture medium

The nitric oxide production of two month-old human H1 cortical cultures after 30 minutes treatment of NMDA or 2 hrs oxygen-glucose deprivation medium was assessed using manufacturer instructions with the Measure-iT High-Sensitivity Nitrite Assay Kit (Life Technologies).

PARP-1 knockout in human cortical neuronal culture using CRISPR/Cas9

PARP-1 sgRNAs (#2, GTGGCCCACCTTCCAGAAGC; #3, ATACCAAAGAAGGGAGTAGC) were synthesized and subcloned into lentiCRISPR vector (Addgene, pXPR_001, plasmid 49535). Lentiviral vectors were co-transfected into HEK293FT cells with the lentivirus packaging plasmids pVSVg and psPAX2 using FuGENE® HD. Supernatants containing virus were collected 48 and 72 hours post transfection, passed through nitrocellulose filter (0.45 µm) and applied on cells in culture. At 8–12 weeks post-differentiation, human cortical neurons were transduced with LentiCRISPR lentivirus carrying control sgRNA or PARP-1 sgRNAs. Cells were then challenged with NMDA or oxygen-glucose deprivation at 5 days after transduction, and cell death was assessed by PI/Hoechst stain 24 hours later. Another batch of cells was collected at 5 days after transduction and forwarded to western blotting for the PARP-1 expression levels.

Western blot

SDS-PAGE and transfer were performed according to laboratory protocol with slight modification. In brief, cultured cells were lysed in RIPA buffer containing 1% Triton, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM NaF, 10 mM Na4P2O7, 2 mM Na3VO4, and EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics) in PBS (pH7.4). Protein extracts were separated by 4–12% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred at constant voltage of 80 V for 150 min at 4°C from the SDS to PVDF membranes. Membrane were then blocked with 5% non-fat milk and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Antibodies used were anti-PAR (Trevigen, 4336-APC-050), Actin (Cell Signaling, 5125), PARP-1 (BD, 611039), β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, #5125S). After washes with TBST (TBS with 0.1% Tween-20), membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 hr at RT. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by the enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (ECL, Pierce) on X-ray film and quantified using the image software TINA.

Electrophysiological recordings

Whole cell voltage clamp recordings: whole-cell configuration using an EPC-10 amplifier (HEKA Elektronik, Germany).Patch-clamp recordings from iPSCs derived neurons were made using recording electrodes of 8–10 MΩ were pulled from Corning Kovar Sealing #7052 glass pipettes (PG52151-4, WPI, USA) by a Flaming-Brown micropipette puller (Sutter Instrument Co., USA). Extracellular solution (in mM): NaCl, 125; KCl, 2.5; D-glucose, 25; NaHCO3, 25; NaH2PO4, 1.25; CaCl2, 1; MgCl2, 1; 5% CO2 and 95% O2 bubbled, pH 7.4. Intracellular solutions contained (in mM): KMeSO4, 135; NaCl,8; ATP-Mg, 2; Na3GTP, 0.1; EGTA, 0.3; HEPES, 10; and pH 7.2. Action potentials (APs) recording were obtained with current clamp configuration. Spontaneous mini-excitatory post synaptic currents (mEPSCs) were obtained with voltage clamp configuration, the membrane potential was hold at −70 mV and picrotoxin 100 µM; TTX 0.5 µM were in the extracellular solution; For inhibitory post synaptic currents (IPSCs) recording, CNQX, 10 µM, MK801, 10 µM were in the extracellular solution. Spontaneous mEPSCs , mIPSCs recordings were acquired and stored digitally using the data acquisition/analysis package PULSE (HEKA Electronik, Germany). Potential recordings were acquired at 6 kHz and filtered at 3 kHz. We used MiniAnalysis 6 (Synaptosoft, Decatur, GA) to detect mEPSCs and mIPSCs events, create cumulative amplitude histograms of the pooled data.

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as mean ± s.e.m. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism and noted in the text and figure legends. Information on sample size (n, given as a number) for each experimental group/condition, statistical methods and measures are available in all relevant figure legends. Unless otherwise noted, significance was assessed as P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Comparison of human forebrain neuron differentiation method

Fig. S2. Neural induction of human iPSCs by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling enhances the efficiency of neural conversion via the RONA method.

Fig. S3. Isolated FOXG1+ forebrain progenitors preserve excitatory and inhibitory neurogenic potential.

Fig. S4. Development regulates the excitatory/inhibitory network formation and synaptic scaling.

Fig. S5. NMDA induces human cortical neuron cell death.

Fig. S6. PARP activation in male versus female human ESC cells.

Data file S1. Gene ontology and enrichment analysis for genes expressed in FOXG1 progenitors

Investigating cell death in human cortical neurons.

Studying mechanisms of cell death in human neurons has been hampered by the lack of human neuronal cultures that exhibit a balanced network of excitatory and inhibitory synapses. Xu et al. now describe a method to culture human neurons with a representative ratio of both excitatory and inhibitory neurons from human embryonic stem cells or inducible pluripotent stem cells. Using this new method they show that human neurons die in a nitric oxide and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 dependent manner. These cultures can be used to study mechanisms of neurotoxicity in human disorders that involve cortical neurons.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grants from MSCRFII-0429 and MSCRFII-0125 to V.L.D. 2013-MSCRF-0054 to J.-C.X., 2013-MSCRF-0028 to J.F. 2014-MSCRFE-0758 to S.M.E, NIH/NINDS NS67525 and NIH/NIDA DA00266 to T.M.D and V.L.D. T.M.D. is the Leonard and Madlyn Abramson Professor in Neurodegenerative Diseases.

Footnotes

Author contributions: J.-C.X., J.F., T.M.D. and V.L.D. designed the experiments. J.-C.X. and J.F. differentiated cortical neurons from human ESCs and iPSCs. J.-C.X. and J.F. performed immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy studies and carried out neurotoxicity studies on the neurons derived from human ESCs or iPSCs. X.W. carried out electrophysiology studies. X.W. and X.Y. analyzed electrophysiology data. S.M.E carried out the RNAseq experiment and analyzed the RNAseq data. T.-I.K., L.C., J.Z., Z.C., H.J. and R.C. analyzed the data. J.-C.X., J.F., T.M.D. and V.L.D. wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Wonders CP, Anderson SA. The origin and specification of cortical interneurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:687–696. doi: 10.1038/nrn1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marin O. Interneuron dysfunction in psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:107–120. doi: 10.1038/nrn3155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lodato S, Rouaux C, Quast KB, Jantrachotechatchawan C, Studer M, Hensch TK, Arlotta P. Excitatory projection neuron subtypes control the distribution of local inhibitory interneurons in the cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2011;69:763–779. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shi Y, Kirwan P, Smith J, Robinson HP, Livesey FJ. Human cerebral cortex development from pluripotent stem cells to functional excitatory synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:477–486. doi: 10.1038/nn.3041. S471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espuny-Camacho I, Michelsen KA, Gall D, Linaro D, Hasche A, Bonnefont J, Bali C, Orduz D, Bilheu A, Herpoel A, Lambert N, Gaspard N, Peron S, Schiffmann SN, Giugliano M, Gaillard A, Vanderhaeghen P. Pyramidal neurons derived from human pluripotent stem cells integrate efficiently into mouse brain circuits in vivo. Neuron. 2013;77:440–456. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pasca SP, Portmann T, Voineagu I, Yazawa M, Shcheglovitov A, Pasca AM, Cord B, Palmer TD, Chikahisa S, Nishino S, Bernstein JA, Hallmayer J, Geschwind DH, Dolmetsch RE. Using iPSC-derived neurons to uncover cellular phenotypes associated with Timothy syndrome. Nat Med. 2011;17:1657–1662. doi: 10.1038/nm.2576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goulburn AL, Alden D, Davis RP, Micallef SJ, Ng ES, Yu QC, Lim SM, Soh CL, Elliott DA, Hatzistavrou T, Bourke J, Watmuff B, Lang RJ, Haynes JM, Pouton CW, Giudice A, Trounson AO, Anderson SA, Stanley EG, Elefanty AG. A targeted NKX2.1 human embryonic stem cell reporter line enables identification of human basal forebrain derivatives. Stem Cells. 2011;29:462–473. doi: 10.1002/stem.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JE, O'Sullivan ML, Sanchez CA, Hwang M, Israel MA, Brennand K, Deerinck TJ, Goldstein LS, Gage FH, Ellisman MH, Ghosh A. Investigating synapse formation and function using human pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3005–3010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007753108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li XJ, Zhang X, Johnson MA, Wang ZB, Lavaute T, Zhang SC. Coordination of sonic hedgehog and Wnt signaling determines ventral and dorsal telencephalic neuron types from human embryonic stem cells. Development. 2009;136:4055–4063. doi: 10.1242/dev.036624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma L, Hu B, Liu Y, Vermilyea SC, Liu H, Gao L, Sun Y, Zhang X, Zhang SC. Human embryonic stem cell-derived GABA neurons correct locomotion deficits in quinolinic acid-lesioned mice. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10:455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe K, Ueno M, Kamiya D, Nishiyama A, Matsumura M, Wataya T, Takahashi JB, Nishikawa S, Muguruma K, Sasai Y. A ROCK inhibitor permits survival of dissociated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:681–686. doi: 10.1038/nbt1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Y, Weick JP, Liu H, Krencik R, Zhang X, Ma L, Zhou GM, Ayala M, Zhang SC. Medial ganglionic eminence-like cells derived from human embryonic stem cells correct learning and memory deficits. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:440–447. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maroof AM, Keros S, Tyson JA, Ying SW, Ganat YM, Merkle FT, Liu B, Goulburn A, Stanley EG, Elefanty AG, Widmer HR, Eggan K, Goldstein PA, Anderson SA, Studer L. Directed differentiation and functional maturation of cortical interneurons from human embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:559–572. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicholas CR, Chen J, Tang Y, Southwell DG, Chalmers N, Vogt D, Arnold CM, Chen YJ, Stanley EG, Elefanty AG, Sasai Y, Alvarez-Buylla A, Rubenstein JL, Kriegstein AR. Functional maturation of hPSC-derived forebrain interneurons requires an extended timeline and mimics human neural development. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;12:573–586. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mariani J, Simonini MV, Palejev D, Tomasini L, Coppola G, Szekely AM, Horvath TL, Vaccarino FM. Modeling human cortical development in vitro using induced pluripotent stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:12770–12775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202944109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marchetto MC, Carromeu C, Acab A, Yu D, Yeo GW, Mu Y, Chen G, Gage FH, Muotri AR. A model for neural development and treatment of Rett syndrome using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell. 2010;143:527–539. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brennand KJ, Simone A, Jou J, Gelboin-Burkhart C, Tran N, Sangar S, Li Y, Mu Y, Chen G, Yu D, McCarthy S, Sebat J, Gage FH. Modelling schizophrenia using human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2011;473:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang SC, Wernig M, Duncan ID, Brustle O, Thomson JA. In vitro differentiation of transplantable neural precursors from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1129–1133. doi: 10.1038/nbt1201-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu H, Xu J, Pang ZP, Ge W, Kim KJ, Blanchi B, Chen C, Sudhof TC, Sun YE. Integrative genomic and functional analyses reveal neuronal subtype differentiation bias in human embryonic stem cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13821–13826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706199104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi Y, Kirwan P, Smith J, MacLean G, Orkin SH, Livesey FJ. A human stem cell model of early Alzheimer's disease pathology in Down syndrome. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:124ra129. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boissart C, Poulet A, Georges P, Darville H, Julita E, Delorme R, Bourgeron T, Peschanski M, Benchoua A. Differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells of cortical neurons of the superficial layers amenable to psychiatric disease modeling and high-throughput drug screening. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3:e294. doi: 10.1038/tp.2013.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tornero D, Wattananit S, Gronning Madsen M, Koch P, Wood J, Tatarishvili J, Mine Y, Ge R, Monni E, Devaraju K, Hevner RF, Brustle O, Lindvall O, Kokaia Z. Human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cortical neurons integrate in stroke-injured cortex and improve functional recovery. Brain. 2013;136:3561–3577. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bilican B, Livesey MR, Haghi G, Qiu J, Burr K, Siller R, Hardingham GE, Wyllie DJ, Chandran S. Physiological normoxia and absence of EGF is required for the long-term propagation of anterior neural precursors from human pluripotent cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wen Z, Nguyen HN, Guo Z, Lalli MA, Wang X, Su Y, Kim NS, Yoon KJ, Shin J, Zhang C, Makri G, Nauen D, Yu H, Guzman E, Chiang CH, Yoritomo N, Kaibuchi K, Zou J, Christian KM, Cheng L, Ross CA, Margolis RL, Chen G, Kosik KS, Song H, Ming GL. Synaptic dysregulation in a human iPS cell model of mental disorders. Nature. 2014;515:414–418. doi: 10.1038/nature13716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Bartley DA, Uhl GR, Snyder SH. Mechanisms of nitric oxide-mediated neurotoxicity in primary brain cultures. J Neurosci. 1993;13:2651–2661. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-06-02651.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dawson VL, Dawson TM, London ED, Bredt DS, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide mediates glutamate neurotoxicity in primary cortical cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:6368–6371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gonzalez-Zulueta M, Ensz LM, Mukhina G, Lebovitz RM, Zwacka RM, Engelhardt JF, Oberley LW, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Manganese superoxide dismutase protects nNOS neurons from NMDA and nitric oxide-mediated neurotoxicity. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2040–2055. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-02040.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sattler R, Xiong Z, Lu WY, Hafner M, MacDonald JF, Tymianski M. Specific coupling of NMDA receptor activation to nitric oxide neurotoxicity by PSD-95 protein. Science. 1999;284:1845–1848. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5421.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hebert JM, Fishell G. The genetics of early telencephalon patterning: some assembly required. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:678–685. doi: 10.1038/nrn2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eiraku M, Watanabe K, Matsuo-Takasaki M, Kawada M, Yonemura S, Matsumura M, Wataya T, Nishiyama A, Muguruma K, Sasai Y. Self-organized formation of polarized cortical tissues from ESCs and its active manipulation by extrinsic signals. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:519–532. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chambers SM, Fasano CA, Papapetrou EP, Tomishima M, Sadelain M, Studer L. Highly efficient neural conversion of human ES and iPS cells by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:275–280. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gaspard N, Bouschet T, Hourez R, Dimidschstein J, Naeije G, van den Ameele J, Espuny-Camacho I, Herpoel A, Passante L, Schiffmann SN, Gaillard A, Vanderhaeghen P. An intrinsic mechanism of corticogenesis from embryonic stem cells. Nature. 2008;455:351–357. doi: 10.1038/nature07287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Debnath J, Muthuswamy SK, Brugge JS. Morphogenesis and oncogenesis of MCF-10A mammary epithelial acini grown in three-dimensional basement membrane cultures. Methods. 2003;30:256–268. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Debnath J, Brugge JS. Modelling glandular epithelial cancers in three-dimensional cultures. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:675–688. doi: 10.1038/nrc1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kadoshima T, Sakaguchi H, Nakano T, Soen M, Ando S, Eiraku M, Sasai Y. Self-organization of axial polarity, inside-out layer pattern, and species-specific progenitor dynamics in human ES cell-derived neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:20284–20289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315710110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turrigiano GG, Nelson SB. Homeostatic plasticity in the developing nervous system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:97–107. doi: 10.1038/nrn1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shepherd JD, Rumbaugh G, Wu J, Chowdhury S, Plath N, Kuhl D, Huganir RL, Worley PF. Arc/Arg3.1 mediates homeostatic synaptic scaling of AMPA receptors. Neuron. 2006;52:475–484. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miyamoto T, Petrus MJ, Dubin AE, Patapoutian A. TRPV3 regulates nitric oxide synthase-independent nitric oxide synthesis in the skin. Nat Commun. 2011;2:369. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan M, Siegel C, Zeng Z, Li J, Liu F, McCullough LD. Sex differences in the response to activation of the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase pathway after experimental stroke. Exp Neurol. 2009;217:210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hansen DV, Rubenstein JL, Kriegstein AR. Deriving excitatory neurons of the neocortex from pluripotent stem cells. Neuron. 2011;70:645–660. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma T, Wang C, Wang L, Zhou X, Tian M, Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Li J, Liu Z, Cai Y, Liu F, You Y, Chen C, Campbell K, Song H, Ma L, Rubenstein JL, Yang Z. Subcortical origins of human and monkey neocortical interneurons. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1588–1597. doi: 10.1038/nn.3536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bredt DS, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide: a physiologic messenger molecule. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:175–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.001135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pasca AM, Sloan SA, Clarke LE, Tian Y, Makinson CD, Huber N, Kim CH, Park JY, O'Rourke NA, Nguyen KD, Smith SJ, Huguenard JR, Geschwind DH, Barres BA, Pasca SP. Functional cortical neurons and astrocytes from human pluripotent stem cells in 3D culture. Nat Methods. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yizhar O, Fenno LE, Prigge M, Schneider F, Davidson TJ, O'Shea DJ, Sohal VS, Goshen I, Finkelstein J, Paz JT, Stehfest K, Fudim R, Ramakrishnan C, Huguenard JR, Hegemann P, Deisseroth K. Neocortical excitation/inhibition balance in information processing and social dysfunction. Nature. 2011;477:171–178. doi: 10.1038/nature10360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turrigiano GG. The self-tuning neuron: synaptic scaling of excitatory synapses. Cell. 2008;135:422–435. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mattson MP, Rychlik B, You JS, Sisken JE. Sensitivity of cultured human embryonic cerebral cortical neurons to excitatory amino acid-induced calcium influx and neurotoxicity. Brain Res. 1991;542:97–106. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91003-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gupta K, Hardingham GE, Chandran S. NMDA receptor-dependent glutamate excitotoxicity in human embryonic stem cell-derived neurons. Neurosci Lett. 2013;543:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hardingham GE, Patani R, Baxter P, Wyllie DJ, Chandran S. Human embryonic stem cell-derived neurons as a tool for studying neuroprotection and neurodegeneration. Mol Neurobiol. 2010;42:97–102. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8136-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samdani AF, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Nitric oxide synthase in models of focal ischemia. Stroke. 1997;28:1283–1288. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.6.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samdani AF, Newcamp C, Resink A, Facchinetti F, Hoffman BE, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Differential susceptibility to neurotoxicity mediated by neurotrophins and neuronal nitric oxide synthase. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4633–4641. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04633.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choi DW, Maulucci-Gedde M, Kriegstein AR. Glutamate neurotoxicity in cortical cell culture. J Neurosci. 1987;7:357–368. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.07-02-00357.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murase S, Owens DF, McKay RD. In the newborn hippocampus, neurotrophin-dependent survival requires spontaneous activity and integrin signaling. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7791–7800. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0202-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Eliasson MJ, Sampei K, Mandir AS, Hurn PD, Traystman RJ, Bao J, Pieper A, Wang ZQ, Dawson TM, Snyder SH, Dawson VL. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase gene disruption renders mice resistant to cerebral ischemia. Nat Med. 1997;3:1089–1095. doi: 10.1038/nm1097-1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fatokun AA, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Parthanatos: mitochondrial-linked mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171:2000–2016. doi: 10.1111/bph.12416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang Z, Huang PL, Panahian N, Dalkara T, Fishman MC, Moskowitz MA. Effects of cerebral ischemia in mice deficient in neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Science. 1994;265:1883–1885. doi: 10.1126/science.7522345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Y, Kim NS, Haince JF, Kang HC, David KK, Andrabi SA, Poirier GG, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) binding to apoptosis-inducing factor is critical for PAR polymerase-1-dependent cell death (parthanatos) Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra20. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang J, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide activation of poly(ADP-ribose) synthetase in neurotoxicity. Science. 1994;263:687–689. doi: 10.1126/science.8080500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanganahalli BG, Joshi PG, Joshi NB. NMDA and non-NMDA receptors stimulation causes differential oxidative stress in rat cortical slices. Neurochem Int. 2006;49:475–480. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Y, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Poly(ADP-ribose) signals to mitochondrial AIF: a key event in parthanatos. Exp Neurol. 2009;218:193–202. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fertuzinhos S, Krsnik Z, Kawasawa YI, Rasin MR, Kwan KY, Chen JG, Judas M, Hayashi M, Sestan N. Selective depletion of molecularly defined cortical interneurons in human holoprosencephaly with severe striatal hypoplasia. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:2196–2207. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Comparison of human forebrain neuron differentiation method

Fig. S2. Neural induction of human iPSCs by dual inhibition of SMAD signaling enhances the efficiency of neural conversion via the RONA method.

Fig. S3. Isolated FOXG1+ forebrain progenitors preserve excitatory and inhibitory neurogenic potential.

Fig. S4. Development regulates the excitatory/inhibitory network formation and synaptic scaling.

Fig. S5. NMDA induces human cortical neuron cell death.

Fig. S6. PARP activation in male versus female human ESC cells.

Data file S1. Gene ontology and enrichment analysis for genes expressed in FOXG1 progenitors