INTRODUCTION

Between 2001 and 2013, marijuana use among US adults more than doubled, many states legalized marijuana use, and attitudes toward marijuana became more permissive.1 In aggregated 2007–2012 data, 3.9% of pregnant women and 7.6% of non-pregnant reproductive-aged women reported past-month marijuana use.2 Although the evidence is mixed, human and animal studies suggest that prenatal marijuana exposure may be associated with poor offspring outcomes (e.g., low birthweight; impaired neurodevelopment).3 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that pregnant women and women contemplating pregnancy be screened for and discouraged from using marijuana and other substances.4 Whether marijuana use has changed over time among pregnant and non-pregnant reproductive-aged women is unknown.

METHODS

Women age 18–44 years old from the annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) from 2002 through 2014 were analyzed. The surveys used in-person audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) about substance use and other behaviors in nationally representative samples of the non-institutionalized US population; average response rates since 2002 were 75%.5 Among participants reporting lifetime use of marijuana or hashish, recency of use was assessed with the question: “How long has it been since you last used marijuana or hashish?” Responses included, “within the past 30 days”; “more than 30 days ago but within the past 12 months”; “more than 12 months ago”.5 Among pregnant and non-pregnant women, log-Poisson regression (SUDAAN 11.0.1) was used to estimate and test trends in the adjusted prevalences of past-month and past-year marijuana use over time, controlling for complex survey design, age, race/ethnicity, family income, and education. Differences in trends over time were examined by pregnancy status and age (18–25 years, 26–44 years). Results were considered statistically significant at p<0.05 (2-sided). Informed oral consent was obtained. The Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board waived review of this study.

RESULTS

Of the women (N=200,510), 29.5% were 18–25 years old and 70.5% 26–44 years old; 61.0% were White, 13.7% Black, 17.2% Hispanic, and 8.1% other race/ethnicity; 59.2% had some college education; 55.9% had annual family incomes <$50,000; 5.3% (n=10,587) were pregnant.

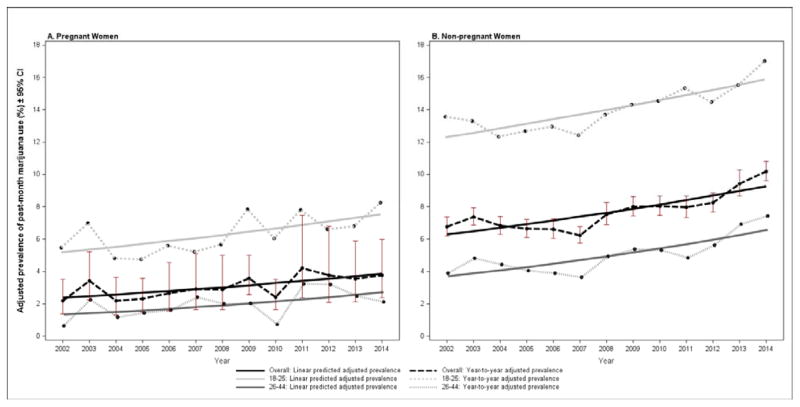

Among all pregnant women, the adjusted prevalence of past-month marijuana use increased from 2.37% (95% CI, 1.85–3.04) in 2002 to 3.85% (95% CI, 2.87–5.18) in 2014 (prevalence ratio [PR]=1.62; 95% CI, 1.09–2.43) (Table). The adjusted prevalence of past-month marijuana use was highest among those age 18–25 years, reaching 7.47% (95% CI, 4.67–11.93) in 2014 (Figure), significantly higher (p=0.02) than among those age 26–44 years (2.12%, 95% CI, 0.74–6.09). However, increases over time did not differ by age (p=0.76). Past-year use was higher overall, reaching 11.63% (95% CI, 9.78–13.82) in 2014, with similar trends over time.

Table.

Trends in prevalence of marijuana use in pregnant and non-pregnant women, 2002–2014 (NSDUH)a

| Adjusted Prevalenceb | Prevalence Ratio (95% CI)f | Test for difference in prevalence ratiosg | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 N=15,284c |

2014 N=15,318d |

||||||||

| n | % | (95% CI) | n | % | (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| Past-month Marijuana usee | |||||||||

| Pregnant Women | 40 | 2.37 | (1.85, 3.04) | 43 | 3.85 | (2.87, 5.18) | 1.62 | (1.09, 2.43) | 0.64 |

| Non-Pregnant Women | 1531 | 6.29 | (6.02, 6.57) | 1673 | 9.27 | (8.90, 9.65) | 1.47 | (1.38, 1.58) | |

| Past-year Marijuana usee | |||||||||

| Pregnant Women | 134 | 8.64 | (7.32, 10.19) | 115 | 11.63 | (9.78, 13.82) | 1.35 | (1.05, 1.72) | 0.73 |

| Non-Pregnant Women | 2809 | 12.37 | (12.05, 12.70) | 2824 | 15.93 | (15.48, 16.40) | 1.29 | (1.23, 1.35) | |

Data are from the U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)

Adjusted prevalence estimates are from the “linear predicted” prevalence model described in footnote “a” of the Figure.

Sample sizes in 2002: pregnant women, n=797; non-pregnant women, n=14,487.

Sample sizes in 2014: pregnant women, n=735: non-pregnant women, n=14,583.

Past-month marijuana use was defined as responding “within the past 30 days” to the question, “How long has it been since you last used marijuana or hashish?”. Past-year marijuana use was defined as responses of “within the past 30 days” or “more than 30 days ago but within the past 12 months”. Pre-processing of missing variables by Predictive Mean Neighborhood imputation and recoding is done prior to public release of the NSDUH datasets.5 Because the analyses used the NSDUH’s imputed variables, there were no missing data. N’s represent the actual number of participants in the survey and are not weighted values.

Prevalence ratios are the ratio of the adjusted prevalence estimates from 2014 divided by the adjusted prevalence estimates from 2002; Ratios and 95% confidence intervals are from log-Poisson regressions. Confidence intervals for prevalence ratios that do not include 1.00 within the lower and upper levels indicate statistically significant increasing trends in marijuana use.

The test for difference in prevalence ratios is the p-value of the pregnancy*year interaction in the log-Poisson regression. This test indicates whether the ratio of the prevalence ratios for pregnant versus non-pregnant women differs significantly from 1.00. Non-significant (p>0.05) p-values indicate insufficient evidence to conclude that the prevalence ratios differ.

Figure.

Year-to-year prevalencea of past-month marijuana useb, pregnant and non-pregnant women, overall and by age, 2002–2014

a“Year-to-year” and “Linear predicted” adjusted prevalence estimates are from log-Poisson regressions. Models controlled for race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other non-Hispanic minorities), family income ($0–19,999, $20,000–49,999, $50,000–74,999, $75,000+), age (18–25, 26–34, 35–44), education (less than high school, high school, at least some college), year (year was categorical in the “year-to-year” model, and continuous in the “linear predicted model”), pregnancy status, pregnancy*year interaction, covariate*pregnancy interactions and complex survey design. 95% confidence bars are shown for “Year-to-year” adjusted prevalence estimates for the overall group. Percent of variability in dichotomous marijuana use explained by the model with year as a continuous variable was 6% (McFadden’s pseudo-R2); the ratio of the pseudo-R2 statistics for the models with year as a continuous vs. categorical variable is 0.98, indicating strong evidence for a linear trend.

bPast-month marijuana use was defined as responding “within the past 30 days” to the question, “How long has it been since you last used marijuana or hashish?”.

cData are from the U.S. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Sample size across all years combined: Pregnant women (n=10,587), non-pregnant women (n=189,923). N’s represent actual number of participants, not weighted values.

In non-pregnant women, prevalences of past-month use (2014: 9.27% [95% CI, 8.90–9.65]) and past-year use (2014: 15.93% [95% CI, 15.48–16.40]) were higher overall, with similar trends over time. Increases over time in past-month marijuana use did not differ by pregnancy status (p=0.64).

DISCUSSION

Among pregnant women, the prevalence of past-month marijuana use increased 62% from 2002–2014. Prevalence was highest among 18–25 year olds, indicating that young women are at greater risk for prenatal marijuana use. Study limitations are noted. Self-reported marijuana use may lead to underreporting due to social desirability and recall biases. However, use of ACASI helps reduce such biases,5 and the increases over time observed in this study are consistent with increases over time in marijuana-related outcomes shown in other studies that did not rely on self-reports, supporting the validity of the findings.6 Additionally, future studies should address dose, frequency of use, and clinical outcomes.

These results offer an important step toward understanding trends in marijuana use among women of reproductive age. Although the prevalence of past-month use among pregnant women (3.85%) is not high, the increases over time and potential adverse consequences of prenatal marijuana exposure3 suggest further monitoring and research are warranted. To ensure optimal maternal and child health, practitioners should screen and counsel pregnant women and women contemplating pregnancy about prenatal marijuana use.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse: grant number T32DA031099 (Brown; P.I. Hasin), R01DA037866 (P.I. Martins), R01DA034244 (P.I. Hasin); and the New York State Psychiatric Institute (Hasin, Wall).

The funding organizations and sponsoring agencies had no further role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Data Archive provided the public use data files for NSDUH, which was sponsored by the Office of Applied Studies of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration. The first author had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Contributors

All authors made substantial contributions to the manuscript: Dr. Brown designed the study, wrote the first and intermediate drafts, and was responsible for the final draft of the manuscript. Drs. Shmulewitz, Wall, and Mr. Sarvet conducted the statistical analyses. Drs. Hasin, Shmulewitz, and Martins made substantial contributions to the writing of subsequent drafts. All authors consulted on the analytic plan, interpretation of the results, edited and approved the final versions of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hasin DS, Saha TD, Kerridge BT, et al. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(12):1235–1242. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ko JY, Farr SL, Tong VT, Creanga AA, Callaghan WM. Prevalence and patterns of marijuana use among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(2):201.e201–201.e210. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Calvigioni D, Hurd YL, Harkany T, Keimpema E. Neuronal substrates and functional consequences of prenatal cannabis exposure. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(10):931–941. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0550-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 637: Marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(1):234–238. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000467192.89321.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Methodological summary and definitions. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hasin DS, Grant BF. NESARC findings on increased prevalence of marijuana use disorders-consistent with other sources of information. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(5):532. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]