Abstract

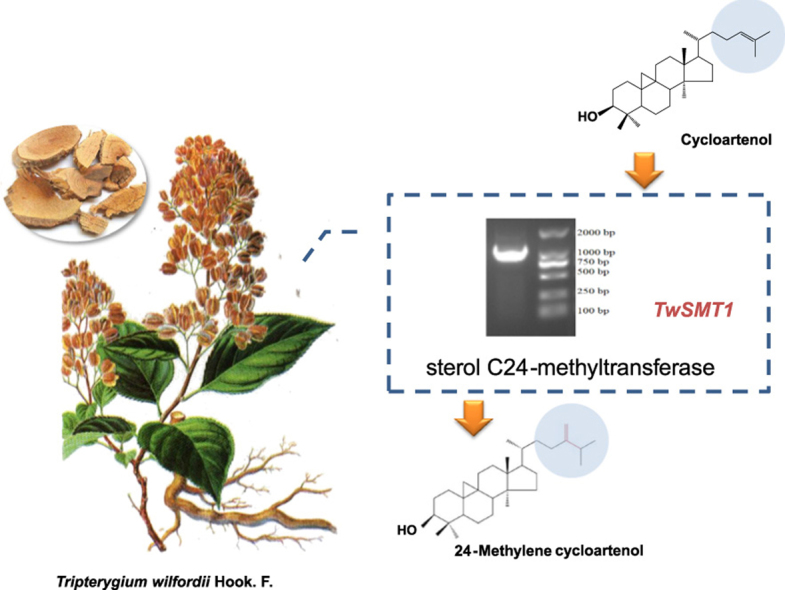

Sterol C24-methyltransferase (SMT) plays multiple important roles in plant growth and development. SMT1, which belongs to the family of transferases and transforms cycloartenol into 24-methylene cycloartenol, is involved in the biosynthesis of 24-methyl sterols. Here, we report the cloning and characterization of a cDNA encoding a sterol C24-methyltransferase from Tripterygium wilfordii (TwSMT1). TwSMT1 (GenBank access number KU885950) is a 1530 bp cDNA with a 1041 bp open reading frame predicted to encode a 346-amino acid, 38.62 kDa protein. The polypeptide encoded by the SMT1 cDNA was expressed and purified as a recombinant protein from Escherichia coli (E. coli) and showed SMT activity. The expression of TwSMT1 was highly up-regulated in T. wilfordii cell suspension cultures treated with methyl jasmonate (MeJA). Tissue expression pattern analysis showed higher expression in the phellem layer compared to the other four organs (leaf, stem, xylem and phloem), which is about ten times that of the lowest expression in leaf. The results are meaningful for the study of sterol biosynthesis of T. wilfordii and will further lay the foundations for the research in regulating both the content of other main compounds and growth and development of T. wilfordii.

KEY WORDS: Cloning, Cycloartenol C24-methyltransferase, Enzymatic assay, Inducible expression, Tissue expression

Graphical abstract

This paper reported molecular cloning of SMT1 from Tripterygium wilfordii and verified its function of catalyzing cycloartenol to generate 24-methylene cycloartenol by enzymatic reaction in vitro.

1. Introduction

Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. F. is a traditional Chinese medicinal plant that has analgesic and anti-microbial properties, and thus it has been widely used to treat inflammatory diseases1. Moreover, recent research showed that T. wilfordii could treat immune and tumour diseases2, 3, 4.

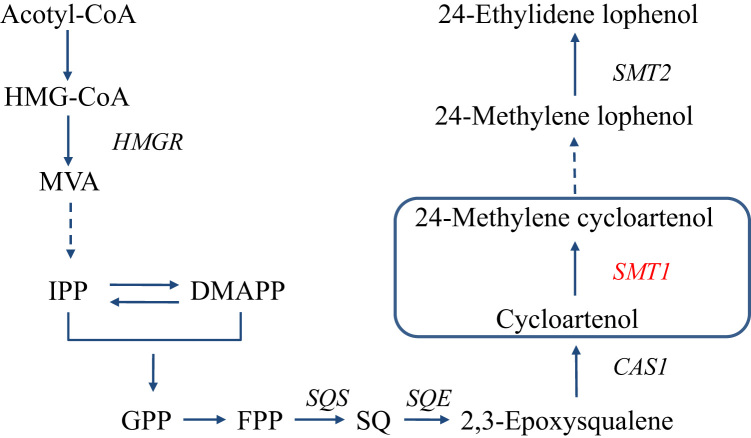

Isoprenoid compounds are main active ingredients of T. wilfordii. Several important enzymes have been cloned and identified for their biosynthetic pathways5, 6. The isoprenoid compounds in T. wilfordii include sterols, chlorophyll, gibberellin, and a variety of terpenes7. Among these, sterols are hydrocarbon derivatives that consist of a four-membered cyclopentanoperhydrophenanthrene ring. Plant sterols are essential components of eukaryotic membranes. They help to maintain membrane integrity and permeability8, participate in mammalian, yeast and plant cell endocytosis and production processes9, and serve as precursors in the brassinosteroid hormone biosynthesis10. In addition, phytosterols can act as signalling molecules in plants,participating in the regulation of various physiological activities, such as photosynthesis, reproduction and immunization11. Sterol C24-methyltransferase (SMTs) have been found to play a key role in the synthesis of steroids with its methyltransferase property12. The analysis of different amino acid sequences in all the cDNAs suggested that SMTs can be separated into two gene families, SMT1 and SMT213. It has been reported that the two compounds play important roles in plant growth and development. The metabolic pathway chart is shown in Fig. 1. It has been indicated that the methylation reactions of cycloartenol and 24-methylene lophenol are catalysed by SMT1 and SMT2, respectively14. The two gene families are involved in the biosynthesis of 24-methyl and 24-ethyl sterols, respectively. Thus, cloning of the plant SMT genes and characterization of the gene products would provide an alternative approach to addressing some of the important questions regarding SMTs, such as the C-24 methylation mechanism and developmental regulation of the enzyme.

Figure 1.

The biosynthetic pathway of phytosterol involving sterol C24-methyltransferase 1 (SMT1) gene and sterol C24-methyltransferase 2 (SMT2) gene. 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutary CoA (HMG-CoA); 3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGR); mevalonate pathway (MVA); isopenteny pyrophosphate (IPP); dimethylally pyrophosphate (DMAPP); gerqnyl pyphosphate (GPP); famesyl pyrophosphate (FPP); squalene synthase (SQS); squalene (SQ); squalene epoxidase (SQE); cycloartenol synthase 1 (CAS1).

Molecular cloning of SMTs was recently achieved in a number of higher plant species, including Astragalus bisulcatus15, Arabidopsis thaliana16, Oryza sativa17, Nicotiana tobacum18, Brassica oleracea19, and Camellia sinensis20. Until now, no SMT gene from T. wilfordii has been cloned. In this paper, we report the isolation and identification of a cDNA encoding SMT1 from T. wilfordii for the first time. The polypeptide encoded by the T. wilfordii cDNA was expressed in E. coli and shown to be an active SMT enzyme. The real-time quantitative PCR analysis of TwSMT1 expression was found to be promoted upon the methyl jasmonate (MeJA) elicitor treatment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant materials

Cell suspensions of T. wilfordii in the study were cultured in Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium (pH 5.8) containing 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D, 0.5 mg/L), cytokinin (KT, 0.1 mg/L), indole-3-butytricacid (IBA, 0.5 mg/L), and sucrose (30 g/L), shaking at 120 rpm (Eppendorf, 5810 R, Germany) 25 °C in dark culture and subculture suspension cells (2 g) in the same medium (25 mL) every 20 days. The plants of T. wilfordii in the tissue expression analysis were obtained from Fujian province and have grown for seven years.

2.2. Cloning of TwSMT1 from T. wilfordii

Total RNA was extracted from T. wilfordii suspension cells stored at —70 °C using the CTAB-LiCl method21. The extract was purified using DNase I (Biolabs, Beijing, China) and an RNA cleaning kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China) to remove contaminating genomic DNAs.

The purified product was reverse transcribed into first-stand 5′-RACE-Ready cDNA and 3′-RACE-Ready cDNA with the SMART RACE cDNA Amplification Kit (Takara Bio Group, Japan). According to mRNA fragments obtained from the transcription data, specific primers (3′-RACE Primer: 5′-TGGATGTAGGATGTGGAATCGGTGGA-3′; 5′-RACE Primer: 5′-TTAGGGCCTCAAGGCATTGTCTGGTC-3′) were designed to amplify 5′ and 3′ cDNA, respectively, followed by ligation into the pEASY-T3 vector (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China) and transfer into E. coli Trans5α competent cells (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). Transformed cells were plated onto Luria-Bertani (LB) solid medium plates containing ampicillin (Amp) and screened using monoclonal colony PCR. Positive bacterial colonies were selected for sequencing to identify and obtain the TwSMT1 full-length sequence.

2.3. Sequence alignments and phylogenetic analyses

The nucleotide and protein sequences were compared using BLAST at the NCBI (http://www.ncbi.NLM.NIH.gov). The ORF was searched using the ORF Finder (www.ncbi.NLM.NIH.gov/Gorf/Gorf.html). The molecular weight (MW) and theoretical isoelectric point (pI) calculations were performed using the Compute pI/MW tool (http://Web.ExPASy.org/compute_pi/). Multiple sequence alignments were performed using DNAMAN 8.0, and phylogenetic analysis was carried out using MEGA 7.0 software to build evolutionary trees.

2.4. Expression of TwSMT1 in E. coli and purification of recombinant protein

Based on the prokaryotic expression vector pMAL-c2X sequence, the restriction endonuclease sites of BamH I and Xba I were selected to design primers from which the stop codon (TAA) has been removed to amplify the TwSMT1 ORF sequence: TwSMT1: 5′-CGGGATCCATGTCGAAGGCTGGGGCGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCTCTAGACTGGGTCTGCCCATTAGGCT-3′ (reverse). According to the instructions of Prime STAR GXL DNA Polymerase (Takara Bio Group, Japan), the PCR reaction conditions were set as follows: 98 °C for 3 min; 35 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 55 °C for 15 s, and 68 °C for 1 min 20 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. After the amplified products were purified, both the vector and the purified products were double-digested with corresponding restriction endonucleases; the enzyme-digested products were purified and ligated with T4 DNA ligase, and then transferred into E. coli Trans5α competent cells. Transformed cells were cultured in LB solid medium with Amp (100 mg/L) for one night, and then a monoclonal plaque was selected for PCR verification and sequencing to obtain the correct recombinant plaque. The new plasmid extracted from the plaque was named pMAL-c2X-TwSMT1.

The recombinant pMAL-c2X-TwSMT1 was transferred into BL21 (DE3) competent cells along with the same transformation of pMAL-c2X as a control. The detected positive plaques were cultured and induced with 1 mmol/L isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside for protein extraction. The extraction procedure was described in Supplementary information, and the purified extract was used for dodecyl sulfate, sodium salt-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) detection.

2.5. Enzyme assays

To identify TwSMT1 functions, enzymatic reactions in vitro were performed with the purified supplement above using the method reported by Schaeffer et al.22. The reaction system contained 0.1 mol/L Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), Tween 80 (0.1%, w/v), glycerol (20%, v/v)), β-mercaptoethanol (1 mmol/L), methyl-3H-AdoMet (100 μmol/L), cycloartenol (100 μmol/L) as a substrate, and purified protein (200 μL); the total volume was 500 μL, and the reaction condition was set at 30 °C for 45 min and ethanolic KOH (100 μL of 12%, w/v) was used as a quenching agent. The sterol compounds in the mixture solution were extracted three times with 600 μL n-hexane, combining the supernatant solution and evaporating the solvent with a pressure blowing concentrator, followed by re-dissolving in n-hexane (200 μL) for gas chromatography—mass spectrometer (GC—MS) detection.

The GC—MS detection was performed using a Thermo TRACE 1310/TSQ 8000 gas chromatography (splitless; injector temperature 250 °C) equipped with a DB-5 ms (30 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm) capillary column, and the program condition was set for 1 min at 60 °C, then increased from 60 to 300 °C at a rate of 30 °C/min, and finally held for 15 min at 300 °C; the flow rate was 1 mL/min with He as a carrier gas. The mass spectrometry detection range was from 50 to 500 m/z.

2.6. Expression analysis of TwSMT1 induced by Methyl Jasmonate

MeJA, as an abiotic elicitor, is widely used in tissue expression analysis for its ability to promote content of secondary metabolites. After the suspension cells of T. wilfordii were induced by MeJA (50 μmol/L) at 0, 1, 4, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 120 h, total RNA extracted with the CTAB method subsequently was reversely transcribed to obtain cDNA for qRT-PCR analysis. Primers for the housekeeping gene, β-actin, were chosen as described in Tong's paper23: β-actin F: 5′-AGGAACCACCGATCCAGACA-3′ and β-actin R: 5′-GGTGCCCTGAGGTCCTGTT-3′. The specific primers (TwSMT1 F: 5′-TCTAACCGCTGTTGGACGA-3′ and TwSMT1 R: 5′-CCCTCAACTAACCCCTCTGC-3′) were designed to amplify the fragment of TwSMT1. The reaction solutions were prepared according to the manufacturer's protocol from the KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Kit, and the amplification conditions were 95 °C for 5 min and 40 cycles of 95 °C for 3 s and 60 °C for 33 s. The experiments were repeated three times for biological and technical replicates, respectively, to ensure the authenticity of the data.

2.7. Tissue expression pattern analysis of TwSMT1

Total RNA was extracted from five organs of T. wilfordii plants, which were the leaf, stem, phloem, xylem and phellem layer. The purified RNA was reversely transcribed into the First Strand cDNA for relative expression study of TwSMT1. The primers for amplifying the housekeeping gene and TwSMT1, as well as the reaction condition of RT-PCR were consistent with inducible expression analyses by MeJA, including the operating time.

3. Results

3.1. Isolation of the cDNA coding for TwSMT1 and sequence analysis

RT-PCR was performed with total RNA from T. wilfordii. TwSMT1 gene fragments were obtained by 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (3′-RACE-PCR) and 5′-RACE-PCR. The full-length cDNA encoding the SMT1 protein was isolated from T. wilfordii. The full-length cDNA of TwSMT1 was 1530 bp. It had a 1041-bp open reading frame (ORF) encoding a 346-amino-acid polypeptide, with a 177 bp 5′ non-coding-region (NCR) and a 312 bp 3′-NCR including a 19 bp poly (A) tail. The predicted TwSMT1 protein has a calculated molecular mass of 38.99 kDa and a theoretical pI of 6.11 (GenBank accession No. KU885950).

3.2. Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequence of TwSMT1 with other SMTs

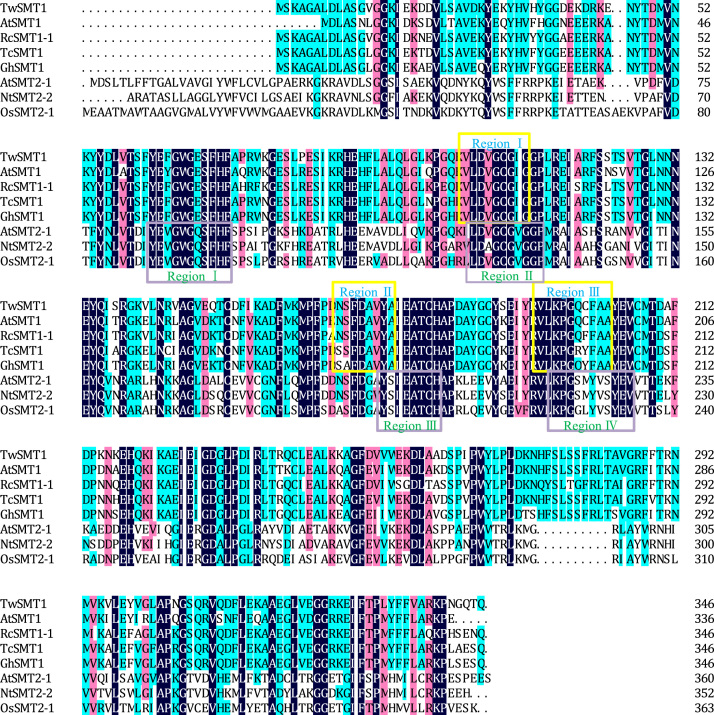

A Blast search of TwSMT1 in the NCBI database showed that the deduced amino acid sequence of TwSMT1 had 75%–86% identity to the SMT1s from A. thaliana, Nicotiana tabacum, O sativa, Zea mays, Ricinus communis, Dioscorea zingiberensis, Theobroma cacao, and Gossypium hirsutum. Sequence comparison revealed that the deduced amino acid sequence contained three methyltransferase regions identified in diverse sterol C24-methyltransferases24. Region I is highly conserved in the protein. Region II contains the invariant central aspartate residue. Region III is located at an interval between the 19-residue C-terminal and region II25. The deduced amino acid sequence of TwSMT1 has 33%–36% identity with the SMT2s from O. sativa, N. tabacum, and A. thaliana. These sequences present highly homologous regions: Region II (IN)LD(A/V)-GCG(V/I)GGP corresponds to the consensus motif described by several authors26. Region III IEATCHAP, a second invariant region, is absent in other methyltransferases and is potentially unique for sterol methyltransferases27. Those regions marked with boxes suggested that the cDNA of T. wilfordii may encode an sterol C24-methyltransferase (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Sequence alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of TwSMT1 with those of related proteins. The three conserved sterol C24-methyltransferase 1 regions and four conserved sterol C24-methyltransferase 2 regions are boxed and numbered with different colours.

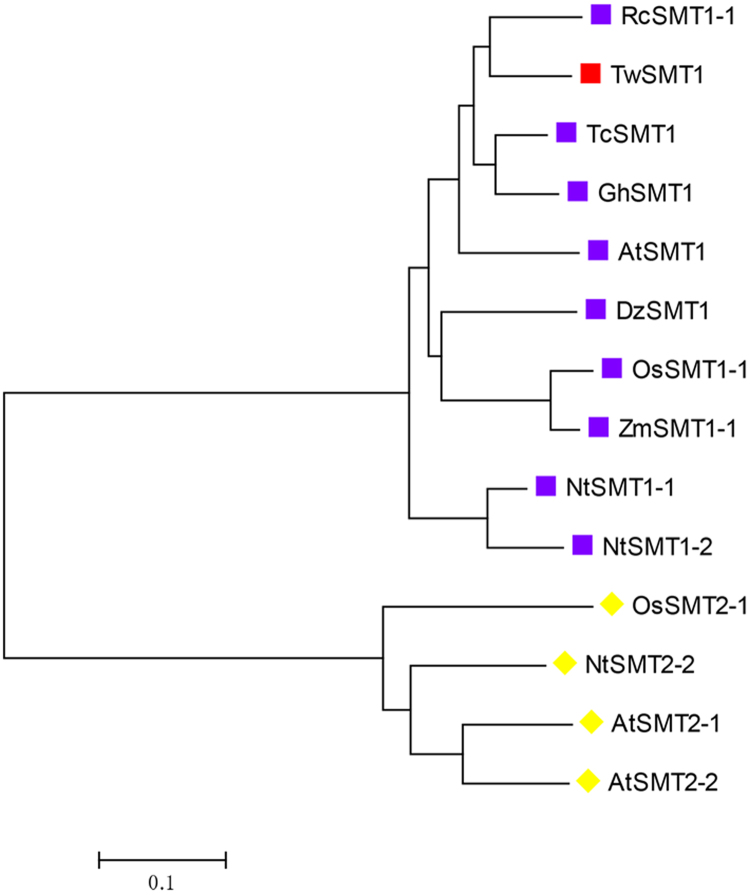

Comparison of all these amino acid sequences allowed a phylogenetic tree of plant SMTs to be built, which was separated into two main groups (Fig. 3). TwSMT1 clustered with 9 SMT1 sequences and OsSMT2 clustered with 3 SMT2 sequences. Moreover, TwSMT1 and R. communis were classified into one cluster. A cluster means that its components had higher homology.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree of the amino acid sequences of sterol C24-methyltransferase from different plants constructed by the neighbour-joining method on MEGA 7.0; GenBank accession numbers: Ricinus communis (RcSMT1-1 AAB62812.1); Theobroma cacao (TcSMT1 XP_007052489.1); Gossypium hirsutum (GhSMT1 AAZ83345.1); Arabidopsis thaliana (AtSMT1 NP_001078579.1); Dioscorea zingiberensis (DzSMT1 CBX33151.1); Oryza sativa (OsSMT1-1 AAC34988.1); Zea mays (ZmSMT1-1 AAB70886.1); Nicotiana tabacum (NtSMT1-1 AAC34951.1); Nicotiana tabacum (NtSMT1-2 AAC35787.1); Oryza sativa (OsSMT2-1 AAC34989.1); Nicotiana tabacum (NtSMT2-2 AAB62807.1); Arabidopsis thaliana (AtSMT2-1 CAA61966.1); Arabidopsis thaliana (AtSMT2-2 AAB62809.1).

3.3. Functional expression and characterization of TwSMT1

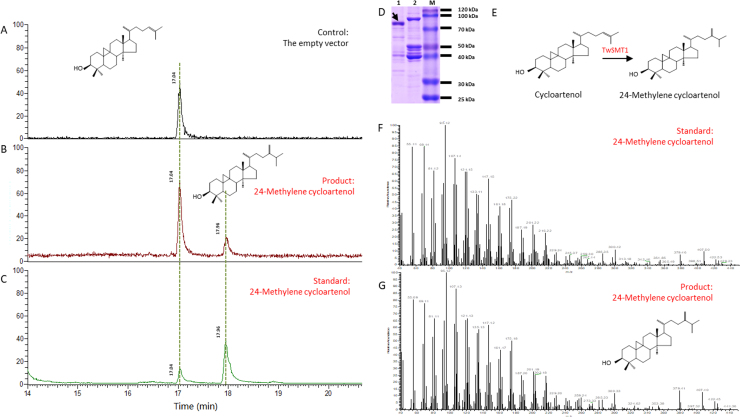

Fig. 4 shows the results of protein expression and GC—MS detection. SDS-PAGE was used to detect purified proteins extracted from BL21(DE3) strains from which pMAL-c2X or pMAL-c2X-TwSMT1 was expressed. The electrophoresis results are shown in Fig. 4D. The control vector expressed an MBP-labelled protein with a molecular weight of 42 kDa, whereas owing to the TwSMT1 protein being 39 kDa, the recombinant plasmid expressed the protein at the position of 80 kDa as the sum of the MBP and TwSMT1 proteins. The results suggest that both the TwSMT1 construct in the pMAL-c2X vector and the empty pMAL-c2X with the MBP label had been successfully expressed in the BL21(DE3) strain, so the extracted protein can be used for further TwSMT1 functional experiments in vitro.

Figure 4.

SDS-PAGE analysis and GC—MS detection results of extract from an enzymatic reaction catalysed by purified pMAL-c2X-TwSMT1 protein and pMAL-c2X protein when using cycloartenol as the substrate. (A) The peak of extraction in the empty vector protein reaction system; (B) The peak of extraction in the recombinant pMAL-c2X-TwSMT1 protein reaction mixture; (C) A control using a 24-methylene cycloartenol standard; (D) 1: The recombinant pMAL-c2X-TwSMT1 overexpressed by isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG) 2: the empty pMAL-c2X overexpressed by IPTG; (E) The function of SMT1 from T. wilfordii; (F) Mass spectrogram of the 24-methylene cycloartenol standard; (G) Mass spectrogram of the product catalysed by recombinant TwSMT1 protein.

The sterol extract from both pMAL-c2X and pMAL-c2X-TwSMT1 in the enzymatic reaction were detected by GC—MS. From the results we can see that, in comparison to a peak of cycloartenol in the pMAL-c2X extract shown in Fig. 4A, a prominent peak whose retention time was 17.96 min was detected in the pMAL-c2X-TwSMT1 protein reaction (Fig. 4B). The experiment was repeated six times, and the same results were obtained. Fig. 4C shows the peak of the predicted product, 24-methylene cycloartenol, which is theoretically SMT1's product when cyclaortenol is the substrate, and it shows the same retention time at 17.96 min as the product in Fig. 4C; thus, they were putatively assigned as the same compound. We then compared the mass spectra of the product (Fig. 4G) and the standard (Fig. 4F), and the figures show nearly identical ion peaks, except for a few low intensity peaks. These results demonstrate that TwSMT1 has the function of catalysing the transformation of cycloartenol to 24-methylene cycloartenol, and it is a cycloartenol-C24-methyltransferase.

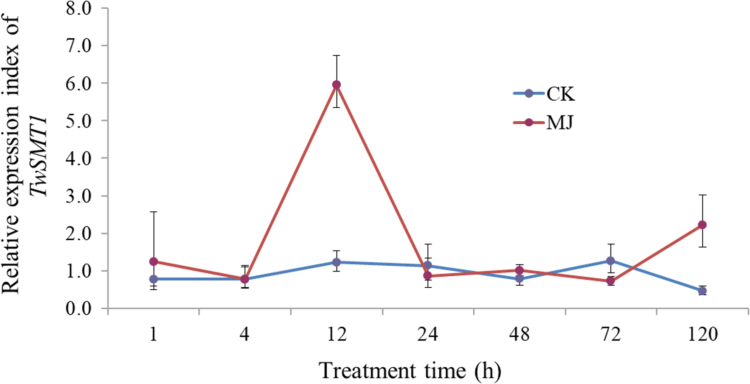

3.4. Inducible expression of TwSMT1

MeJA has the ability to promote the accumulation of secondary metabolites. From Fig. 5, it is clear that the elicitor MeJA works on the expression level of TwSMT1. After the suspension cells were elicited by MeJA, the TwSMT1 transcript levels have an obvious fluctuation especially at 12 h and it is about four times higher than the blank control group. Afterwards, the curve tends to overlap with the control group and stabilize. The methodology can be used to study sterol content accumulation and other sterol genes through transcriptome data mining.

Figure 5.

Expression profile of TwSMT1 when treated with 1 mmol/L methyl jasmonate (MJ) over 120 h. RT-PCR analysis was performed using total RNA isolated from suspension cells of T. Wilfordii. CK, the control group; MJ, the MJ-induced group.

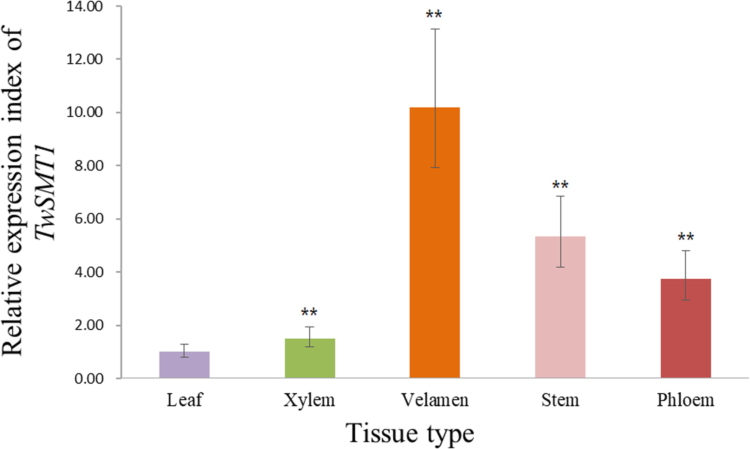

3.5. Tissue expression pattern of TwSMT1

Fig. 6 shows the relative expression level of TwSMT1 in different organs. It shows that phellem layer has the highest expression level, which is about ten times higher than the lowest expression in leaf.

Figure 6.

Tissue expression analysis of TwSMT1 in the leaf, stem, phloem, xylem and phellem layer of T. Wilfordii plants. The asterisks mean that the difference is acceptable when the values of other organs take leaf as a standard (**P < 0.01).

4. Discussion

The enzyme sterol C24-methyltransferase 1 (SMT1) is involved in the biosynthesis of plant sterol, which plays major roles in plant growth and development. In addition, studies have shown that β-sitosterol, a phytosterol belonging to the 24-ethyl sterols, has been isolated from T. wilfordii28, and it has an obvious cholesterol-lowering activity and is widely used in the pharmaceutical industry. In the present study, we have reported the first isolation and characterization of a sterol C24-methyltransferase 1 gene from T. wilfordii. The results showed that TwSMT1 is a 1530-bp cDNA with a 1041-bp ORF predicted to encode a 346-amino acid, 38.62 kDa protein. The results also indicated that the SMT1 obtained belonged to the family of transferases and catalysed the transformation of cycloartenol to 24-methylene cycloartenol. In order to study the inducible expression of TwSMT1 from cell suspensions upon MeJA, we analysized the changes of real-time PCR in various stages. The results showed that MeJA caused a significant increase in TwSMT1 levels in T. wilfordii cell suspensions. Tissue expression analysis showed TwSMT1 has a higher expression in velamen compared to other four organs.

Plant sterols play extremely important roles in every stage of plant growth and development. It is important that SMTs act on the biosynthesis of plant sterols as many researchers have reported. Researchers often use mutant and enzyme inhibitors to study the functions of plant sterols. Mutants of SMT1 show abnormal embryoids and cotyledons with different sizes and numbers29. This result indicates that plant sterols play a crucial role in the process of embryonic development. Mutants of SMT1 show cell shrinkage of root epidermis and cortex, stasis phenomenon of the meristem and elongation region cells in the shape of a circle29, indicating the importance of sterols in normal growth and development of the roots. The orc mutation residing in C-24 SMT1 shows a position disorder of auxin transmission proteins PIN1 and PIN3, indicating that plant sterols could correct the polarity orientation of proteins30.

Sterols play a vital role in the process of eukaryote growth and development. They are not only structural components, but also have important regulatory functions and are precursors for the synthesis of other compounds. Plant sterols participate in almost all processes of plant growth, from the embryo to post-embryonic development. Therefore, they are indispensable to normal plant growth and development. Studies have also shown that consuming more plant sterols can reduce the absorption of cholesterol, and they may be used as therapeutics in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81422053 and 81373906 to Wei Gao and 81325023 to Luqi Huang), and the Support Project of High-level Teachers in Beijing Municipal Universities in the Period of 13th Five-year Plan (CIT&TCD20170324 to Wei Gao), and the Key project at Central Government Level: The Ability Establishment of Sustainable Use for Valuable Chinese Medicine Resources (2060302 to Luqi Huang).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Chinese Pharmaceutical Association.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2017.07.001.

Contributor Information

Luqi Huang, Email: huangluqi01@126.com.

Wei Gao, Email: weigao@ccmu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.Brinker A.M., Ma J., Lipsky P.E., Raskin I. Medicinal chemistry and pharmacology of genus Tripterygium (Celastraceae) Phytochemistry. 2007;68:732–766. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Titov D.V., Gilman B., He Q.L., Bhat S., Low W.K., Dang Y. XPB, a subunit of TFIIH, is a target of the natural product triptolide. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:182–188. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manzo S.G., Zhou Z.L., Wang Y.Q., Marinello J., He J.X., Li Y.C. Natural product triptolide mediates cancer cell death by triggering CDK7-dependent degradation of RNA polymerase II. Cancer Res. 2012;72:5363–5373. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chugh R., Sangwan V., Patil S.P., Dudeja V., Dawra R.K., Banerjee S. A preclinical evaluation of minnelide as a therapeutic agent against pancreatic cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:156ra139. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan H.Y., Su P., Zhao Y.J., Tong Y.R., Liu Y.J., Hu T.Y. Cloning and protein expression of sterol-C-24-methyl transferase 2 in Tripterygiumwilfordii. Acta Pharm Sin. 2016;51:1799–1805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng Q., Tong Y., Wang Z., Su P., Gao W., Huang L. Molecular cloning and functional identification of a cDNA encoding 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase from Tripterygium wilfordii. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2017;7:208. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chappell J. The biochemistry and molecular biology of isoprenoid metabolism. Plant Physiol. 1995;107:1–6. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weete J.D., Parish E.J., Nes W.D. Chemistry, biochemistry, and function of sterols. Lipids. 2000;35:241. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Souza C.M., Pichler H. Lipid requirements for endocytosis in yeast. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:442–454. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.D'Hondt K., Heese-Peck A., Riezman H. Protein and lipid requirements for endocytosis. Ann Rev Genet. 2000;34:255–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grebe M., Xu J., Möbius W., Ueda T., Nakano A., Geuze H.J. Arabidopsis sterol endocytosis involves actin-mediated trafficking via ARA6-positive early endosomes. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1378–1387. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00538-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nes W.D., Zhou W., Ganapathy K., Liu J., Vatsyayan R., Chamala S. Sterol 24-C-methyltransferase: an enzymatic target for the disruption of ergosterol biosynthesis and homeostasis in Cryptococcus neoformans. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2009;481:210–218. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouvier-Navé P., Husselstein T., Benveniste P. Two families of sterol methyltransferases are involved in the first and the second methylation steps of plant sterol biosynthesis. Eur J Biochem. 1998;256:88–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2560088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahier A., Taton M., Bouvier-Navé P., Schmitt P., Benveniste P., Schuber F. Design of high energy intermediate analogues to study sterol biosynthesis in higher plants. Lipids. 1986;21:52–62. doi: 10.1007/BF02534303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pickering I.J., Wright C., Bubner B., Ellis D., Persans M.W., Yu E.Y. Chemical form and distribution of selenium and sulfur in the selenium hyperaccumulator Astragalus bisulcatus. Plant Physiol. 2003;131:1460–1467. doi: 10.1104/pp.014787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellis D.R., Sors T.G., Brunk D.G., Albrecht C., Orser C., Lahner B. Production of Se-methylselenocysteine in transgenic plants expressing selenocysteine methyltransferase. BMC Plant Biol. 2004;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu Y.G., Pilon-Smits E.A., Zhao F.J., Williams P.N., Meharg A.A. Selenium in higher plants: understanding mechanisms for biofortification and phytoremediation. Trends Sci. 2009;14:436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matich A.J., McKenzie M.J., Brummell D.A., Rowan D.D. Organoselenides from Nicotiana tabacum genetically modified to accumulate selenium. Phytochemistry. 2009;70:1098–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyi S.M., Zhou X., Kochian L.V., Li L. Biochemical and molecular characterization of the homocysteine S-methyltransferase from broccoli (Brassicaoleracea var. italica) Phytochemistry. 2007;68:1112–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu L., Jiang C.J., Deng W.W., Gao X., Wang R.J., Wan X.C. Cloning and expression of selenocysteine methyltransferase cDNA from Camellia sinensis. Acta Physiol Plant. 2008;30:167–174. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Del Sal G., Manfioletti G., Schneider C. The CTAB-DNA precipitation method: a common mini-scale preparation of template DNA from phagemids, phages or plasmids suitable for sequencing. Biotechniques. 1989;7:514–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schaeffer A., Bouvier-Navé P., Benveniste P., Hubert S. Plant sterol-C24-methyl transferases: different profiles of tobacco transformed with SMT1 or SMT2. Lipids. 2000;35:263–269. doi: 10.1007/s11745-000-0522-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tong Y., Zhang M., Su P., Zhao Y., Wang X., Zhang X. Cloning and functional characterization of an isopentenyl diphosphate isomerase gene from Tripterygium wilfordii. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2016;63:863–869. doi: 10.1002/bab.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi J., Gonzales R.A., Bhattacharyya M.K. Identification and characterization of an S-adenosyl-l-methionine: Δ24-sterol-C-methyltransferase cDNA from soybean. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9384–9389. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kagan R.M., Clarke S. Widespread occurrence of three sequence motifs in diverse S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferases suggests a common structure for these enzymes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;310:417–427. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ganapathy K., Jones C.W., Stephens C.M., Vatsyayan R., Marshall J.A., Nes W.D. Molecular probing of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae sterol 24-C methyltransferase reveals multiple amino acid residues involved with C2-transfer activity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1781:344–351. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neelakandan A.K., Nguyen H.T., Kumar R., Tran L.S., Guttikonda S.K., Quach T.N. Molecular characterization and functional analysis of Glycine max sterol methyl transferase 2 genes involved in plant membrane sterol biosynthesis. Plant Mol Biol. 2010;74:503–518. doi: 10.1007/s11103-010-9692-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu J., Yang J., Peng F., Zhao J., Huang R., Dai Y. Studies on chemical constitutes of Tripterygium wilfordii hook. J Yunnan Norm Univ. 2003;23:52–53. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jang J.C., Fujioka S., Tasaka M., Seto H., Takatsuto S., Ishii A. A critical role of sterols in embryonic patterning and meristem programming revealed by the fackel mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1485–1497. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Babiychuk E., Bouvier-Navé P., Compagnon V., Suzuki M., Muranaka T., Van Montagu M. Allelic mutant series reveal distinct functions for Arabidopsis cycloartenol synthase 1 in cell viability and plastid biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3163–3168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712190105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material